Abstract

Background

Copper is an essential metal for living organisms as a catalytic co-factor for important enzymes, like cytochrome c oxidase the final enzyme in the electron transport chain. Plasmodium falciparum parasites in infected red blood cells are killed by excess copper and development in erythrocytes is inhibited by copper chelators. Cytochrome c oxidase in yeast obtains copper for the CuB site in the Cox1 subunit from Cox11.

Methods

A 162 amino acid carboxy-terminal domain of the P. falciparum Cox11 ortholog (PfCox11Ct) was recombinantly expressed and the rMBPPfCox11Ct affinity purified. Copper binding was measured in vitro and in Escherichia coli host cells. Site directed mutagenesis was used to identify key copper binding cysteines. Antibodies confirmed the expression of the native protein.

Results

rMBPPfCox11Ct was expressed as a 62 kDa protein fused with the maltose binding protein and affinity purified. rMBPPfCox11Ct bound copper measured by: a bicinchoninic acid release assay; atomic absorption spectroscopy; a bacterial host growth inhibition assay; ascorbate oxidation inhibition and in a thermal shift assay. The cysteine 157 amino acid was shown to be important for in vitro copper binding by PfCox11whilst Cys 60 was not. The native protein was detected by antibodies against rMBPPfCox11Ct.

Conclusions

Plasmodium spp. express the PfCox11 protein which shares structural features and copper binding motifs with Cox11 from other species. PfCox11 binds copper and is, therefore, predicted to transfer copper to the CuB site of Plasmodium cytochrome c oxidase. Characterization of Plasmodium spp. proteins involved in copper metabolism will help sceintists understand the role of cytochrome c oxidase and this essential metal in Plasmodium homeostasis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Mitochondria with the associated electron transport chain are present in most apicomplexans, have small mitochondrial genomes and appear to be present throughout all the stages of their life cycle [1]. Their electron transport chains have sufficient differences to the electron transport chains of their mammalian hosts to make them promising drug targets [1, 2]. Human malaria caused by Plasmodium spp. parasites is the most prevalent apicomplexan infection. The parasite is passed by the bite of an infected mosquito in human infections to the blood of the human host, infects the liver and then red blood cells, which coincides with clinical symptoms. Plasmodium parasites in red blood cells depend predominantly on glycolysis for the generation of ATP and electron micrographs show the presence of a single mitochondrion [3, 4]. Despite a reduced dependence on mitochondria, the parasites are sensitive to drugs targeting the electron transport chain during this stage of development indicating the importance of the pathway for the parasite [1].

Proteins participating in the electron transport chain contain iron and copper to transport electrons leading to the subsequent generation of ATP. Copper is essential for most living organisms as the metal can cycle between the reduced (Cu+) and more stable oxidized (Cu2+) form under physiological conditions and so participate in redox reactions and electron transfer. Copper can be toxic due to its ability to undergo Fenton reactions leading to the generation of toxic reactive oxygen species [5]. Copper can be toxic, can displace metals in proteins, is rarely free in cells and is, therefore, tightly regulated and bound to proteins, like copper chaperones.

During the erythrocytic stage Plasmodium spp. can, like yeast and mammalian cells, import copper via the copper transport protein (Ctr1) expressed initially on the red cell membrane and then the parasitophorous vacuolar membrane [6]. The parasite also obtains copper from the digestion of ingested host erythrocyte Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase [7, 8]. Plasmodium spp. do not express an ATOX-1 (Antioxidant Protein 1) or CCS (Copper Chaperone for Superoxide dismutase) chaperone homologue that shepherd copper to ATPases in the Golgi apparatus or to Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase respectively in mammalian cells [9]. ATPases are involved in the export of copper from cells and Plasmodium express a copper P-ATPase [8] that is important for parasite fertility [10]. Excess copper is toxic for Plasmodium spp. [11] and chelating copper in in vitro growth media with neocuproine or tetrathiomolybdate inhibit the growth of intraerythrocytic parasites [12].

Plasmodium spp. mitochondria have the four complexes of the electron transport chain which includes the copper containing cytochrome c oxidase of complex IV [13]. Cytochrome c oxidase is assembled in many steps, requiring over 30 accessory proteins [14]. The Cox17 protein is a key participant in mitochondrial copper transport to proteins for insertion into cytochrome c oxidase [15]. Plasmodium spp. express Cox17 [16]. Cox17 was first observed in the cytoplasm and mitochondria of yeast which suggested a role in copper transport to mitochondria [17], but subsequent data using Cox17 tethered to the mitochondrial matrix in yeast does not support this suggestion [18]. Cox17 transfers copper to Sco1 and Cox11 which in turn insert copper into the CuA and CuB sites of Cox2 and Cox1 of cytochrome c oxidase [18, 19]. Copper appears to be transported to mitochondria by the phosphate carrier Pic2 in yeast [20] and SLC25A3 in mammalian cells [21].

Cox11 in eukaryotes is attached to the inner mitochondrial membrane via a single transmembrane domain with the N-terminus in the mitochondrial matrix and the C-terminus in the intermembrane space [22,23,24]. The protein metalates the CuB site of Cox1 with copper in cytochrome c oxidase [25]. Cox11 copper is coordinated by two cysteines in a CFCF motif found in the C-terminal domain [23]. Cox11 is essential in yeast for the assembly of cytochrome c oxidase and the activity of cytochrome c oxidase in Arabidopsis [23, 26]. The present study extended the understanding of Plasmodium spp. copper metabolism and the synthesis of cytochrome c oxidase by studying recombinant P. falciparum Cox11 and showing that the recombinant protein binds copper in vitro and in vivo when expressed in Escherichia coli host cells.

Methods

Ethical clearance

All procedures involving animals were approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Animal Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 0045/15/Animal).

Identification of the gene and analysis of Plasmodium spp. Cox11 protein sequences

Plasmodium falciparum cytochrome c oxidase assembly protein PfCox11 (PF3D7_1475300) was identified [6] using a BLASTp search of the Plasmodb.org database with the Human Cox11 protein amino acid sequence (UniProtKB-Q9Y6N1 COX11_HUMAN).

Transmembrane domains in the PfCox11 amino acid sequence (PF3D7_1475300) were identified using the TMHMM 2.0 programme [27]. Multiple sequence alignment was generated with Clustal Omega (http://ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo) [28]. Theoretical molecular weight and isoelectric point were determined using PROTPARAM (http://web.expasy.org/protparam). The P. falciparum Cox11 structure (Fig. 1) was modelled on the Sinorhizobium meliloti SmCox11 homologue NMR structure template (PDB: 1so9) template [24] using the Swiss-Pdb DeepView program [29].

Analysis of Plasmodium spp. Cox11 amino acid sequences. The P. falciparum Cox11 amino acid sequence was aligned with Cox11 from A Theileria, Babesia, Trypanosoma, Arabidopsis, Saccharomyces, Homo and Mus sequences and B Plasmodium reichenowi, Plasmodium berghei, Plasmodium chabaudi, Plasmodium yoelii, Plasmodium vivax, and Plasmodium knowlesi. Key: a: P. falciparum Cox11 transmembrane domain, b: conserved cysteine (P. falciparum C60) and c: conserved CFCF motif (P. falciparum C155 and C157). The cloned P. falciparum sequence is in bold script. C for comparative purposes the protein model for Sinorhizobium meliloti Cox11 (PDB:ISO9) amino acid sequence served as a template (left panel) for homology modelling of the P. falciparum Cox11 amino acid sequence (right panel) and the two models superimposed (middle panel). The S. meliloti and P. falciparum Cox11 Cys-100/102 and 155/157 positions in the conserved CFCF sequence are illustrated

PCR amplification, mutagenesis and cloning of the C-terminal domain of Plasmodium falciparum PfCox11 and mutants

The PfCox11 gene portion coding for the predicted C-terminal domain and equivalent to that found in the mitochondrial intermembrane space for the yeast protein [22] was amplified using the following primers: rPfCOX11Ct-fwd ccGTCGACCAATTATTTTGTCAATCCACAGG and rPfCOX11Ct-rev 5' ttCGTCAGTCAGGAAATAVGCCTTGAGG with added Sal1 and Pst1 restriction endonuclease sites shown in bold. Primers for site-directed mutagenesis [30] for the C60A mutation were rPfCOX11CtC60A-F1 GAAAGACGCGCAGACTAATTCGAGCTC, rPfCOX11CtC60A-R1 GGCCAGTGCCAAGCTTGCCTGCAG, and rPfCOX11CtC60A-F2 GTCG-ACCAATTATTTGCGCAATCCACAGG, rPfCOX11CtC60A-R2 CTGTGGATTGCGCAAATAAT-TGGTCGAC. The C157A mutant was amplified using the following primers: rPfCOX11CtC157A-F1 GAATTCGGATCCTCTAGAGTC rPfCOX11CtC157A-R1 TGCCAAGCTTGCCTGCAG and rPfCOX11CtC157A-F2 CAATGTTTTGCCTTTGAAGAAC, rPfCOX11CtC157A-R2 GTTCTTCA-AAGGCAAAACATTG. The polymerase chain reaction was conducted with a reaction mix (20 µl) containing 1–100 ng template DNA, 0.5 µM of each primer, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 1 U of Phusion DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs) for PCR and site directed mutagenesis, and 1× Taq buffer in a T100™ thermocycler (Bio-Rad, USA). An initial denaturation step (94 °C; 3 min), followed by 35 cycles of denaturation (94 °C; 30 s), annealing (temperature determined by the Tm of the primers, 30 s), elongation (72 °C; 60 s) and final elongation (72 °C; 7 min) steps. Amplicons of the PfCox11-Ct were cloned into the pGEMTeasy vector and the plasmid propagated in JM109 E. coli host cells. The plasmid with insert was isolated and digested with Sal1 and Pst1 restriction endonucleases. The insert was gel purified and ligated in frame with an N-terminal maltose binding protein (rMPB) in the pMal-c2x expression vector digested with the same two restriction endonucleases (New England Biolabs, USA). The sequence of the cloned gene was confirmed by DNA sequencing (Central Analytical Facility, Stellenbosch University, South Africa). The mutated gene fragments were PCR amplified, digested with Sal1and Pst1 restriction endonuclease and ligated into the pMal-c2x vector as described above.

Expression and purification of recombinant MBPPfCox11Ct and mutants

Recombinant pMal-c2c vectors containing the PfCox11Ct insert were transformed into competent E. coli BL21 host cells. A single E. coli transformant was picked from an agar plate and grown overnight (16 h) in 10 ml 2 × YT medium (30 °C, 200 rpm) containing 100 µg/ml ampicillin. A 1:100 dilution of the culture was added to 400 ml 2 × YT medium with 100 µg/ml ampicillin and grown (30 °C, 200 rpm) to an OD600 between 0.5 and 0.6. Recombinant protein expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG with additional ampicillin. The bacterial cells were pelleted by centrifugation (4000×g, 4 °C, 10 min) and the supernatant discarded. The pellet was resuspended in 10% of the original culture volume of buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 200 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4) and lysed with 9 freeze–thaw cycles (−196 °C and 37 °C) followed by sonication on ice (3 cycles, 30 s/burst, 30 s on ice between sonication). The lysates were centrifuged (12,000×g, 4 °C, 25 min). The supernatant was added to a 1 ml amylose resin (New England Biolabs, USA) equilibrated with Tris–HCl buffer (20 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.4) and was washed with wash buffer (100 mM Tris, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). Bound protein was eluted with the wash buffer containing 0.3 mM maltose and eluted fractions were collected and concentrated with an Amicon Ultra-15 Centrifugation Filter Unit (10 kDa MWCO) by centrifugation (5000×g, 4 °C) [31, 32]. Samples were dialysed at 4 °C against 3 changes of 100 mM Tris–HCl buffer pH 7.4. The Bradford dye binding assay [33] was used to estimate the protein concentration of samples as adapted [34]. Proteins were evaluated on a 12.5% reducing SDS-PAGE gel stained with Coomassie Blue [35].

BCA copper release assay

Purified recombinant rMPB-PfCox11Ct and mutants were tested for their ability to bind copper after purification (in vitro) and during expression (in vivo). Escherichia coli cells expressing the protein intended for in vitro or in vivo copper binding studies were grown in a medium containing 0 or 0.5 mM CuCl2 respectively, added during induction of protein expression [16, 36]. The protein was affinity purified as described above. In the in vitro studies, 10 µM purified rMBPPfCox11Ct was incubated with 20-fold molar excess of CuCl2 (15 min; 23 °C). Ascorbate (0 or 10 mM) was included in the reaction mix to reduce free copper. Excess unbound copper was removed by dialysis (2 × 2 h; 23 °C followed by 16 h; 4 °C). The dialysed sample was mixed with 30% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid (3:1 v/v) and centrifuged (12,000×g; 2 min; 23 °C). Released copper was detected by mixing with bicinchoninic acid (BCA) solution (0.15 mM BCA, 0.9 M NaOH, 0.2 M HEPES) with or without 2 mM ascorbate and the absorbance read at 354 nm [37]. To chelate copper, and thus render it unavailable for binding to a copper binding protein, EDTA was added to the BCA release assay prior to the addition of copper. In the in vivo assay, 10 µM purified rMBPPfCox11Ct grown in the presence of copper was affinity purified and added to the BCA copper release assay.

Atomic absorption spectroscopy

The amount of copper bound to the recombinant proteins was quantified by atomic absorption spectroscopy (AAS) using an Agilent Varian AA280FS atomic absorption spectrophotometer. The reference solution was a certified atomic absorption standard (Fischer Scientific Co.) prepared at 1.0 ± 0.01 mg/ml in dilute nitric acid. Samples were prepared as described for the in vitro copper binding assessment using the BCA release assay.

Growth of E. coli bacteria expressing recombinant proteins in the presence of toxic concentrations of copper

The influence of rMBPPfCox11Ct on the growth of E. coli host cells in the presence of toxic concentrations of copper was determined. Overnight cultures of E. coli cells alone or expressing the recombinant MBP or rMBPPfCox11Ct proteins were grown in 2 × YT medium (30 °C, 200 rpm) containing ampicillin (100 μg/ml). At an OD600 between 0.5 and 0.6, recombinant expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG and additional ampicillin (100 μg/ml) and 0 or 8 mM copper added and bacterial growth (30 °C, 200 rpm) monitored at OD600 for 6 h.

Inhibition of copper-catalysed ascorbate oxidation assay

Copper catalyses the oxidation of ascorbate in vitro, and the ability of rMBPPfCox11Ct and mutants to bind copper and inhibit the ascorbate oxidation reaction was assessed. The pH of a 2 mM ascorbate stock solution was adjusted to pH 4.5 with dilute NaOH. The reaction mixture contained 5 µM protein, 120 µM ascorbic acid and 8 µM CuCl2 (1 ml total volume). Recombinant proteins were added to the reaction mixture and the absorbance of the solution at 255 nm was followed for 300 s at 25 °C [6, 38].

Differential scanning fluorescence to determine rMBPPfCox11Ct thermal melt temperature

The assay described by Niesen et al. [39] with minor modifications was followed. Protein (0.5 μg) in phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and 10 × SYPRO Orange in 25 μl. The assay was run in Xtra-clear qPCR tubes (Star labs) in a Rotor-Gene 6000 RT-PCR machine (Corbett). The condition parameters set were high resolution melt (HRM) which has an λ excitation at 470 nm and an λ emission at 570 nm, which was used to measure the SYPRO Orange fluoresce probe. A temperature range of 25–90 °C was used with a ramp temperature of 0.3 °C/s. The change in fluorescence/change in temperature (dF/dT) was calculated and the dF/dT data was plotted against temperature and the highest dF/dT point on each peak was referred to as the Tm.

Antibody production

The amino acid sequence of rMBPPfCox11Ct was used to identify immunogenic epitopes with Predict7 software [40]. The peptide sequence KIQF(Abu)F(Abu)EEQMLNAKEEM where internal cysteines were replaced with alpha aminobutyric acid (Abu), was synthesized by GeneScript, USA. The C-terminal cysteine residue was added for m-maleimidobenzoyl-N-hydroxysuccinimide ester (MBS) coupling to rabbit serum albumin [41]. Two Hy-line brown laying hens were immunized with the peptide-carrier conjugate equivalent to 200 µg peptide or 50 µg affinity purified rMBPPfCox11Ct per immunization, emulsified with Freund’s complete adjuvant for the first immunization and Freund’s incomplete adjuvant for three subsequent immunizations at 2-week intervals. Chicken IgY from the yolks of eggs collected 4–16 weeks after the first immunization, was isolated using the PEG6000 precipitation method [42]. The anti-peptide IgY and anti-rMBPPfCox11Ct IgY was affinity purified using a peptide or rMBPPfCox11Ct affinity column prepared by coupling the respective molecules to a Sulfolink™ or Aminolink™ resin according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Plasmodium berghei parasites

Plasmodium berghei parasites (donated by P. Smith University of Cape Town, originally from A.P. Waters Glasgow University) were propagated in male BALB/c mice by intraperitoneal injection of the parasite stabilate (1 × 107 parasitized mouse red blood cells) [43]. Parasitaemia was monitored daily on a Giemsa-stained thin blood smear of tail blood [44]. Once parasitaemia reached a suitable level, mice were bled, and the blood collected in a heparinized vacuum test tube.

SDS-PAGE and western blotting

Native and recombinant proteins were detected with affinity purified anti-peptide antibodies in a western blot [45]. Blood from infected mice was washed twice in PBS and resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris–HCl, 10 mM Na2EDTA, 1% (v/v) Triton X-100, pH 7.4). The lysates (approximately 105 parasites) and recombinant proteins were separated on a 12.5% reducing SDS-PAGE gel, transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked by incubation in 0.5% (w/v) non-fat milk (Amresco, USA) in Tris-buffered saline (TBS, 20 mM Tris–HCl, 200 mM NaCl, pH 7.4). The membrane was incubated in an appropriate dilution of primary antibody followed by the secondary antibody diluted in 0.5% (w/v) BSA in TBS. The blots were developed by incubation in either 0.06% (w/v) 4-chloro-1-naphthol/0.0015% (v/v) H2O2 or Pierce™ enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) western blotting substrate. Primary antibodies were affinity purified chicken anti- KIQF(Abu)F(Abu)EEQMLNAKEEM peptide IgY (2.5 µg/ml), chicken anti-rPfCox11Ct protein IgY (1 µg/ml) or mouse monoclonal anti-MBP IgG (1:12 000) (New England Biolabs, USA). Detection antibodies were rabbit anti-chicken IgY-horse radish peroxidase (HRPO) conjugate (1:5000) (Jackson Immuno-Research Laboratories, USA) or goat anti-mouse IgG-HPRO conjugate (1:5000) (Roche, Germany).

Results

Bioinformatics

Choveaux et al. [6] identified a putative Cox11 using the human Cox11 amino acid sequence as the input sequence, alongside 13 copper-dependent protein orthologues in the P. falciparum genome from a BLASTp search of the PlasmoDB genome database [46]. The Plasmodium Cox11 sequences lack the 51–61 amino acid N-terminal extension found in the Theileria, Babesia, Arabidopsis, Homo and Mus sequences and as a result have 4, instead of the 5 or 6 cysteines seen in the plant, yeast or mammalian Cox11 sequences (Fig. 1a). The P. falciparum Cox11 gene is found on chromosome 14, and codes for a 228 amino acid protein sequence [47]. The Plasmodium spp. sequences, like all other characterized Cox11 sequences, have a 19 amino acid transmembrane domain (Fig. 1a, b) followed by a conserved cysteine (Cys-60) and 94 amino acids towards the C-terminus a conserved CFCF motif (Cys-155 and Cys-157, Fig. 1a, b). There is an 11 amino acid region around the CFCF motif that includes Lys-152 that is 100% conserved in multiple species (Fig. 1a). These three cysteines and the lysine are essential for yeast Cox1 activity [48]. Plasmodium falciparum also contains a conserved tyrosine (Pf Tyr-139) while the hydrophobic valine found in the Saccharomyces cerevisiae (Val-226) homologue [48] is replaced with an isoleucine (Pf Ile-173). The P. falciparum sequence shares 44% identity with the human sequence and 71% identity with other Plasmodium spp. Cox11 sequences. The protein has a predicted molecular mass of 26.807 kDa, a pI of 8.71 [47] and the amino acid sequence is predicted to target the protein to the mitochondrial inner membrane [47] (http://busca.biocomp.Unibo.it/deepmito).

Expression profiling during the different stages of the P. falciparum life cycle showed that PfCox11 and PfCox1 are expressed during the sporozoite, trophozoite and gametocyte stages of parasite development [49] and interestingly levels of Cox11 peak 30 h and Cox1 40 h post-erythrocytic invasion [50]. Plasmodium spp. Cox11 proteins share the classical structural domains and functional motifs found in well-characterized Cox11 proteins from other species.

Homology model

The NMR-solved structure of S. meliloti Cox11 (PDB:ISO9) [24] served as the template to generate a P. falciparum Cox11 (PfCox11) homology model (Fig. 1c). Banci et al. [24] describe the structure as having an immunoglobulin-like fold consisting of 10 β strands organized into a β-barrel. The two P. falciparum cysteines (Pf Cys-155 and Cys-157) in the CFCF sequence within the highly conserved 11 amino acid motif are on a surface loop on the structure shown in the diagram (Fig. 1c). The two cysteines are also located on a surface loop in the Alphafold predicted P. falciparum Cox11 protein model (https://www.uniprot.org/uniprot/Q8IK85). The Cys-60 amino acid residue is in the N-terminus of the protein and was not included in the S. meliloti model (PDB:ISO9) [24].

Recombinant expression of rMBPPfCox11Ct and detection with anti-MBP antibodies

The sequence coding for 162 amino acids of the carboxy-terminal domain of the PfCox11 gene was cloned and expressed as a recombinant maltose binding fusion protein and called “rMBPPfCox11Ct”. A His tag fusion protein was insoluble and was not used. The identity of the cloned sequence was confirmed by DNA sequencing. The recombinant MBP fusion protein was affinity purified from E. coli host cell lysates using an amylose affinity matrix (Fig. 2a). A 62 kDa protein that corresponds to the 62.745 kDa, predicted from the cloned gene sequence, and consists of 19 kDa of PfCox11 and 43 kDa of the maltose binding protein fusion partner, was expressed and detected in a western blot by anti-MBP antibodies (Fig. 2b). Truncated versions of the recombinant protein, including a prominent 45 kDa protein, corresponding to the size of the rMPB fusion partner, were also detected by the anti-MBP antibodies. About half a milligram of protein (0.49 mg) was obtained from each gram of wet bacterial pellet (Table 1).

Evaluation of rMBPPfCox11Ct on SDS-PAGE and detection with anti-MBP antibodies on a western blot. Proteins were separated on a 12.5% reducing SDS-PAGE gel and stained with Coomassie blue (A) and (B) the same proteins on an identical gel electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with mouse anti-MBP monoclonal antibody and detected with goat anti-mouse IgG-horse radish peroxidase (HRPO) conjugate and enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL). Mw: molecular weight marker; lane 1, soluble E. coli lysate, and fractions from an amylose affinity matrix: unbound (lane 2); wash (Lane 3) and eluted in the presence of maltose (lanes 4–8)

rMBPPfCox11Ct and mutants bind Cu+ in vitro

Recombinant copper chaperones, PfCox17 and the C-terminus of recombinant PfCtr-1, along with copper chaperones from different sources have been shown to bind copper in vitro. Purified rMBPPfCox11Ct was exposed to both Cu+ and Cu2+ in vitro before the protein was denatured and the oxidative state of the released Cu determined by the BCA assay in the presence or absence of the reducing agent, ascorbate. The rMBPPfCox11Ct bound cuprous ions (Fig. 3). To identify which particular cysteine residues are involved in copper binding, the PfCox11 Cys-60 and Cys-157 residues were substituted with alanine by site-directed mutagenesis [51]. Single C60A, and C157A mutants and a double C60A/C157A mutant were generated. The amino-acid sequences of the mutants were confirmed by sequencing the respective DNA sequences in the host plasmid. The remaining cysteine (Cys-155) was not mutated as the DNA sequence around the cysteine is AT rich and primer sequences would lack specificity for the targeted site in the experimental approach used. There was no significant difference in the binding of copper in vitro by the rMBPPfCox11Ct protein or its derivatives containing the three different mutations in the BCA release assay (Fig. 3). The proteins containing the C157A and the C60A/C157A double mutations, like the wild type protein, bound copper in the assay, but appeared to bind marginally less copper than the wild type protein (Fig. 3). The rMPB fusion partner did bind some copper, as has been described before, and was included as a control in all experiments [6].

Copper binding to rMBPPfCox11Ct and mutants in vitro measured by the BCA release assay. Affinity purified rMBPPfCox11Ct or mutants C60A, C157A, C60A–C157A or rMPB were incubated with CuCl2 in the absence (−) or presence ( +) of ascorbic acid in vitro. Copper was detected with the BCA release assay without (open bars) or with (closed bars) the addition of ascorbic acid. Copper chloride was equimolar to protein. Results are the means ± SE of triplicate measurements from duplicate samples. A two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison tests were conducted on the results of samples incubated with CuCl2 in the presence of ascorbate. Comparisons are between rMBPPfCox11Ct and mutants and rMPB where *P < 0.001

EDTA inhibition of copper binding and detection of copper with atomic absorption spectroscopy

EDTA has been reported to chelate copper and remove copper from the media and the chelated copper is unavailable to bind to molecules [52]. Therefore, it was expected that copper chelated to EDTA would no longer be available for binding to the rMBPPfCox11Ct. The binding of Cu+ to rMBPPfCox11Ct was inhibited by EDTA as measured by the BCA-release assay (Fig. 4a). The binding of copper measured by the BCA-release assay was confirmed (Fig. 4b) with atomic absorption spectroscopy [37]. The rMPB fusion partner bound small amounts of copper as seen in the assays above. All the above assays indicate both rMPB and to a greater extent rMBPPfCox11Ct bound Cu+.

Copper binding to rMBPPfCox11Ct is inhibited by EDTA and measured by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Affinity purified rMBPPfCox11Ct or rMPB were incubated with and without EDTA and with CuCl2 in vitro. Copper was detected with the BCA release assay without (open bars) or with (closed bars) the addition of ascorbic acid. Results are the means ± SE of triplicate measurements from duplicate samples. A two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison tests were conducted on results of samples incubated with CuCl2 in the presence of ascorbate. Comparisons are between rMBPPfCox11Ct or rMPB without and with EDTA, *P < 0.001. A, B Affinity purified rMBPPfCox11Ct or rMPB was incubated with CuCl2 in the absence (open bars) or presence (solid bars) of ascorbic acid and bound copper was quantified using atomic absorption spectroscopy at 324.5 nm. Data is the mean ± SD of duplicate samples.

Binding of copper to rMBPPfCox11Ct and rMBPPfCox11Ct mutants in vivo in E. coli host cells

The ability of rMBPPfCox11Ct and the protein with mutated cysteine residues to bind Cu+ in an in vivo cellular environment was evaluated with two different approaches. Initially, E. coli host bacteria with plasmids containing the PfCox11Ct DNA sequence or the three mutated sequences were grown in the presence of CuCl2 at non-toxic concentrations of copper and recombinant fusion protein expression induced, followed by protein isolation. Copper binding to rMBPPfCox11Ct expressed in copper rich medium was determined with the BCA-release assay. In the second approach the plasmid containing host cells were grown in the presence of increasing levels of copper and host bacteria growth patterns monitored.

rMBPPfCox11Ct isolated from E. coli grown in the presence of CuCl2 bound copper in the in vivo copper enriched environment. The bound copper was in the Cu+ oxidation state, as inferred from the BCA release assay in the presence and absence of ascorbic acid (Fig. 5). Unlike in the in vitro BCA release assay (Fig. 3), there was more copper bound to the rMBPPfCox11Ct and there was a significant difference in copper binding between the rMBPPfCox11Ct native sequence and the proteins with mutated cysteines. The rMBPPfCox11Ct containing the C60A mutation, bound the same levels of copper as the protein without the mutation (Fig. 5). However, the rMBPPfCox11Ct protein with the C157A mutation bound significantly less copper and the protein with the double C60A/C157A mutant bound the least amount of copper (Fig. 5).

Copper binding to rMBPPfCox11Ct and mutants in vivo measured by the BCA release assay. E. coli host cells expressing rMBPPfCox11Ct or the mutants C60A, C157A and C60A/C157 or rMPB were grown in the presence of 0.5 mM CuCl2. The expressed protein was affinity purified and copper was detected with the BCA release assay without (open bars) or with (closed bars) the addition of ascorbic acid. Results are the means ± SE of triplicate measurements from duplicate samples. A two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni multiple comparison tests were conducted on the results comparing: rMBPPfCox11Ct and mutants wrt rMPB *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.001, rMBPPfCox11Ct wrt C157A and C60A/157A ##P < 0.001, C157A wrt C60A/C157A $$P < 0.001

In the second assay 8 mM copper chloride inhibited the growth of E. coli without a plasmid as seen by a plateau in the E. coli growth curve after copper addition (Fig. 6a). When expression of rMBPPfCox11Ct was induced it was proposed that the protein would bind copper and enable the host bacteria to continue to grow in the presence of otherwise toxic levels of CuCl2. The bacteria expressing rMBPPfCox11Ct continued to divide and grow, though at a lower rate compared to bacteria in the absence of CuCl2 (Fig. 6b). When bacteria expressing the rMBPPfCox11Ct protein with the C60A mutant were exposed to 8 mM CuCl2 like the non-mutant (wild type) sample, they grew but at a lower rate than the non-mutant. Bacteria expressing the rMBPPfCox11Ct protein with the single C157A or the double C60A/C157A mutation stopped dividing, indicating that the mutants did not bind copper and did not rescue the host cells in the presence of these toxic concentrations of copper (Fig. 6b).

Growth of E. coli host cells expressing rMBPPfCox11Ct and mutants in the presence of copper. E. coli (BL21) growth was monitored at OD600 in the absence or presence of toxic concentrations of copper. A E. coli (BL21) expressing pMal-c2x. B E. coli (BL21) expressing rMBPPfCox11Ct, or the single C60A, C157A or double C60A/C157A mutant. Arrows indicate the addition of copper and IPTG to the growth media

The data from the two in vivo experiments suggests that Cys-60 appears not to be involved in the binding of copper, whilst Cys-157 appears to be involved in copper binding.

Analysis of copper binding by rMBPPfCox11Ct using the rate of ascorbate oxidation

Proteins binding copper in vitro can influence the rate of copper-catalyzed oxidation of ascorbate and this has been used to determine copper binding by PfCox17, PfCtr-1 and other proteins [6, 16, 37]. The rate of copper-catalyzed ascorbate oxidation was monitored at 255 nm in the presence or absence of the native and mutated rMBPPfCox11Ct proteins. The addition of 8 mM CuCl2 caused a rapid oxidation of ascorbate indicated by a decrease in absorbance at 255 nm (Fig. 7). Oxidation of ascorbate was inhibited by rMBPPfCox11Ct and inhibited to a similar extent by the C60A mutant protein. Both the C157A and the C60A/C157A mutant proteins inhibited ascorbate oxidation to a lesser extent than the native rMBPPfCox11Ct protein. The inhibition of ascorbate oxidation is interpreted as the binding of copper by the proteins. These results follow the same pattern as the growth inhibition assay and support the importance of the Cys-157 for the binding of copper by PfCox11.

rMBPPfCox11Ct and mutants inhibit the copper-catalyzed oxidative degradation of ascorbate. Ascorbate alone and copper catalyzed ascorbate oxidation was followed by measuring absorbance at 255 nm. Inhibition of copper catalyzed ascorbate oxidation was determined by adding rMBPPfCox11Ct or the mutants C60A, C157A and C60A/C157A to the assay before addition of CuCl2

Thermal shift analysis of rMBPPfCox11-Ct

Thermal shift analysis measures the thermal denaturation of a protein [53]. The denaturation profile of a protein can be influenced by the presence of metal ions, drug–protein or protein–protein interactions [39]. The differential scanning fluorescence (DSF) analysis presented in Fig. 8 showed a small decrease in the Tm of rMPB alone in the presence (49.12 ± 0.25 °C) or absence of copper (49.61 ± 0.35 °C). There was a more pronounced decrease in the Tm of rMBPPfCox11Ct in the presence of copper from 55.68 ± 0.12 °C to 52.42 ± 0.49 °C, a ΔTm of −2.26 °C. The decrease in the thermal transition temperature for rMBPPfCox11Ct supports the binding of copper to the protein (Fig. 8).

The effect of copper on the differential scanning fluorimetry first derivative of the fluorescence profile of rMBPPfCox11Ct. rMBPPfCox11Ct or rMPB with or without bound copper in phosphate buffer pH 7.4 was incubated with SYPRO® orange. The raw fluorescence data was measured from 25 to 90 °C and the first derivative calculated and presented. One of three different experiments with identical peaks is presented

Chicken IgY antibodies against rMBPPfCox11Ct and the peptide detect the recombinant and native PfCox11 protein

Antibodies were raised in chickens against the affinity purified rMBPPfCox11Ct fusion protein and against a peptide in the carboxy-terminus of the protein, coupled to a rabbit albumin carrier. The peptide (KIQF(Abu)F(Abu)EEQMLNAKEEM) was chosen based on hydropathy, antigenicity and surface probability parameters, conservation of the sequence in different species of human infecting Plasmodium spp. and the presence of the conserved CFCF motif (see Fig. 1b). The antibodies were isolated and affinity purified [54, 55] using the rMBPPfCox11Ct protein or peptide coupled to an affinity matrix. The affinity purified rMBPPfCox11Ct protein was previously shown to be detected by anti-MPB antibodies (Fig. 2b). The affinity purified rMBPPfCox11Ct protein was separated on an SDS-PAGE gel (Fig. 9a, c) and detected by IgY antibodies against the recombinant protein (Fig. 9b) and antibodies against the synthetic KIQF(Abu)F(Abu)EEQMLNAKEEM peptide (Fig. 9d). The anti-peptide antibodies raised against a synthetic peptide derived from the Plasmodium falciparum Cox11 amino acid sequence confirmed the identity of the recombinant rMBPPfCox11Ct protein (Fig. 9d). All the antibodies detected the 62 kDa recombinant fusion protein and did not detect any E. coli host cell proteins or red blood cell proteins (Fig. 9b, d).

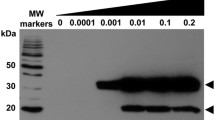

Detection of Plasmodium spp. Cox11 and rMBPPfCox11Ct with chicken anti-rMBPPfCox11Ct IgY and chicken anti-KIQF{Abu}F{Abu}EEQMLNAKEEM peptide IgY. A 12.5% SDS-PAGE reducing gel stained with Coomassie blue (A, C) and the same proteins on an identical gel electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose (B, D) and probed with B chicken anti-rMBPPfCox11-Ct IgY or D chicken anti-KIQF{Abu}F{Abu}EEQMLNAKEEM peptide IgY. A–D Mw molecular weight markers; lane 1, uninfected red blood cell lysate; lane 2, untransformed E. coli BL21(DE3) host cell lysate; lane 3, E. coli expressing rMBPPfCox11Ct; lane 4, affinity purified rMBPPfCox11Ct and lane 5, affinity purified recombinant rMPB. E Coomassie Blue stained reference gel and proteins transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with F chicken anti-Plasmodium lactate dehydrogenase peptide IgY and G chicken anti-rMBPPfCox11Ct IgY. E–G Mw molecular mass marker (Mw); lysates of uninfected (lane 1) and (lane 2) P. berghei infected BALB/c mouse red blood cells. Chicken IgY antibodies were detected with rabbit anti-IgY-HRPO secondary antibody and ECL

Affinity purified chicken IgY antibodies against rMBPPfCox11Ct were used to probe lysates of uninfected and P. berghei infected mouse erythrocytes separated on an SDS-PAGE gel (Fig. 9e) and transferred to nitrocellulose (Fig. 9g). An anti-Plasmodium LDH antibody against a conserved PLDH common peptide served as a positive control for the assay and detected PbLDH at 37 kDa (Fig. 9f). The antibodies did not detect E. coli host cell proteins or mouse red blood cell proteins in the western blot of the gel. The antibodies detected Plasmodium proteins at 28 kDa corresponding to the size predicted from the genomic sequence, a 38 kDa protein and a possible dimer and tetramer of 58 and 106 kDa, and a very large protein of undetermined molecular mass (Fig. 9g). This data suggests that the recombinant protein represents the native protein and confirms in silico data indicating that Plasmodium spp. parasites express a Cox11 protein [47].

Discussion

Cox11 is an essential protein in multiple organisms inserting copper into the CuB site of the Cox1 protein of the terminal mitochondrial respiratory chain enzyme cytochrome c oxidase. Plasmodium spp. Cox11 has not been studied to date and little is known about both the Plasmodium spp. cuprome and assembly of Plasmodium cytochrome c oxidase. Sixteen proteins of the Plasmodium cytochrome c oxidase complex have been identified [2]. Plasmodium spp. Cox1, which contains the CuB copper moieties, and Cox3, are encoded by a mitochondrial gene, whilst the remaining proteins, like Cox2 with the CuA site and Cox11 are encoded by nuclear genes [2, 47]. Here we have begun to characterize Plasmodium Cox11 using a recombinant truncated section of the carboxy-terminus of the protein.

The Plasmodium spp. Cox11 protein, like the well-characterized Cox11 protein sequences contains a single transmembrane domain (Fig. 1). Tzagoloff et al. [22] proposed that Cox11 is an intrinsic membrane protein in the inner mitochondrial membrane. The C-terminal region of yeast Cox11 can be removed by proteases from mitoplasts indicating its location in the inner mitochondrial membrane space [56] which was confirmed with antibodies [57] and Khalimonchuck et al. [58] proposed an Nin–Cout topology. Given the location of Plasmodium spp. cytochrome c oxidase and the structural features of the Plasmodium Cox11 the Plasmodium spp. protein is proposed to have the same location and topology as yeast Cox11.

The transmembrane region of PfCox11 is followed by a conserved Cys (Cys-60) and a highly conserved 11 amino acid sequence which includes Lys-152 and the CFCF quartet (Cys-155 and Cys-157) seen in Fig. 1A. The cysteines in the CFCF motif map to the same surface accessible position on a loop in the model of PfCox11-Ct and the Banci et al. [24] S. meliloti template model (Fig. 1c). The three cysteines and the Lys residue have been described as essential for Cox11 to insert copper into the CuB site of cytochrome c oxidase [23, 48, 59]. The extensive N-terminal domain, found in yeast, mammalian and plant homologues was shown by proteolytic cleavage studies not to be involved in copper binding [56, 58].

Plasmodium spp. Cox11 is predicted to have a size of 26.8 kDa, similar to the 28 kDa originally described for yeast Cox11 [22]. The gene encoding 228 amino acids of the carboxy-terminus of the protein, without the transmembrane region, was cloned and recombinantly expressed as a 19 kDa section of a 62 kDa rMPB fusion protein and affinity purified on an amylose resin (Fig. 2). Banci et al. [24] expressed Cox11 as a hexahistidine His tag fusion protein from five organisms with the best expression being that of the S. meliloti protein. Carr et al. [23] found that the S. cerevisae Cox11-Ct expressed as a His-Cox11-Ct fusion protein was insoluble, but a thioredoxin fusion protein was soluble. Thompson et al. [59] reported poor yields of a His-Cox11-Ct from Rhodobacter sphaeroides, but obtained “reasonable yields” of a thioredoxin-Cox11-Ct fusion protein. During the present study there was difficulty expressing the protein as a His tag fusion protein and so a rMPB fusion protein (rMBPPfCox11Ct) was engineered, expressed and affinity purified.

To compare the Plasmodium spp. protein to yeast and bacterial proteins [23, 59], three mutated forms of the protein, two with single C60A and C157A mutations and a double C60A/C157A mutation were expressed and affinity purified. The Plasmodium spp. genomes are AT rich and it was consequently not possible in the present study to design suitable primers to modify the Cys-155 residue.

Plasmodium falciparum Cox11 was shown to bind copper in a BCA release assay, by atomic absorption spectroscopy, a bacterial host growth inhibition assay, in an ascorbate oxidation inhibition assay and in a thermal shift assay (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). The in vitro BCA release assay showed no difference in copper binding between the wild type and the C60A mutant, but there were minor, but not significant, differences between the wild type and the C157A or C60A/C157A double mutant (Fig. 3). When the wild type protein was expressed with additional copper in the medium, more copper was bound to the protein as shown by a 50% increase in absorbance values (Fig. 5). The wild type and the C60A mutant showed little difference in copper binding whilst the C157A and the C60A/C157A mutants bound significantly less copper (Fig. 5). The same trend was observed in the growth pattern of E. coli host cells expressing the native and mutated proteins in the presence of growth inhibiting (toxic) concentrations of copper and the ascorbate inhibition assay (Figs. 6, 7). The data indicate that Cys-60 is not important for copper binding in vitro or when the protein is in an in vivo environment, while Cys-157 is essential. The same finding has been reported for R. sphaeroides Cox11 [59]. However, though the Cox11 Cys-60 amino acid is not necessary for Cu binding, the amino acid is essential for the insertion of Cu into the CuB site of Cox1 of cytochrome c oxidase in yeast and bacteria [23, 59]. Though we were not able to mutate the Cys-155 amino acid it is very likely that the three cysteines, P. falciparum Cox11 Cys-60, 155 and 157 residues, like the same cysteines in Cox11 from yeast and bacteria are essential for physiological function [23, 48].

Mutations of several yeast Cox11 amino acid residues have shown that Lys-205, found three amino acid residues N-terminal to the CFCF motif is essential for a functional cytochrome c oxidase [48]. All Plasmodium spp. genomes sequenced to date and a large number of other sequences from multiple species (personal observation) have conserved amino acid residues either side of the CFCF motif including the lysine residue (Fig. 1). Met-224, indicated as essential for the yeast Cox11 sequence, is not present in any Plasmodium homologues (Fig. 1b), Babesia bovis or Theileria parva Cox11 proteins (Fig. 1a) [23]. Banting and Glerum [48] found that mutations of other residues of bacterial Cox11, for example, Tyr-192 and Val-226 impaired Cox11 function. The Tyr-192 is present in all Plasmodium homologues (P. Tyr-139) and the Val-226 in S. cerevisae (Fig. 1a) is present in Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium knowlesi and all rodent Plasmodium Cox11 sequences (9 amino acids Ct to box d in Fig. 1b). Interestingly P. adleri, P. bilicollins, P. blacklocki, P. gaboni, P. reichenowi, P. praefalciparum, P. gallinaceum and P. falciparum (in 16 different isolates) all have an isoleucine (PfCox11 Ile-173) in place of valine in homologues of Cox11 from other species [47]. There is a single base difference at the 5' end of three codons coding for either valine (G) or isoleucine (A), indicating how the change in a single base gives rise to the alternate amino acid, independent of which of the three different codons are employed. These findings strongly support Banting and Glerum’s [48] observation and confirm that in the position occupied by Val-226, a hydrophobic amino acid is essential and can be either valine or isoleucine. Banting and Glerum [48] found that replacing Val-226 with a tryptophan produced a dysfunctional Cox11 showing that a more bulky hydrophobic side chain influences the physiological activity of Cox11.

The expression of P. falciparum Cox11 in vivo is indicated by the functionality of Plasmodium cytochrome c oxidase and mRNA expression data [47, 49, 50]. Affinity purified antibodies raised against the recombinant protein and against a peptide sequence derived from the amino acid sequence of the protein detected the recombinant protein (Fig. 9b, 9d). These antibodies detected the native protein in a lysate of blood stage parasites (Fig. 9g). This confirms that the recombinant protein shares structural features with the native protein and provides physical evidence for the expression of the native protein by the parasite. The antibodies detected five proteins in the parasite lysate. The native protein is 26.8 kDa and a protein of 28 kDa was detected in the western blot (Fig. 9g). The larger protein at 58 kDa may represent a possible Cox11 homodimer or a heterodimer of Cox11 and Cox19 (26.8 and 26.1 kDa) as the two have been shown to interact and co-purify [60]. The 108 kDa protein may represent a Cox11 homotetramer, while the largest protein could represent Cox11 interacting with proteins of the cytochrome c oxidase complex. The western blot could be probed with antibodies against the relevant proteins to support or disprove this suggestion.

Yeast Cox11 can obtain copper from Cox17 [15]. Given the structural similarities between the Plasmodium and yeast proteins shown in this study and by Choveaux et al. [16], it is suggested that Plasmodium Cox11 would also obtain copper from Cox17, which will be evaluated. Yeast Cox11 inserts copper to the CuB site on the Cox1 protein of the cytochrome c oxidase [24, 48, 61]. Expression data for mRNA indicates that PfCox17, PfCox11 and PfCox1 are expressed during the sporozoite, trophozoite and gametocyte stages of parasite development [49] and interestingly expression levels of PfCox17 and PfCox11 peak at 30 h and PfCox1 at 40 h post erythrocytic invasion [50]. This suggests an important role for complex IV during the development from trophozoites to schizonts in red blood cells to be investigated further.

This study has confirmed: the presence of native Cox11 in Plasmodium spp., that PfCox11 binds copper in vitro or an in vivo E. coli environment and that Cys-157 is essential for copper binding in vitro. The gene for PfCox11 has a mutagenesis index score and a mutant fitness score of 0.145 and −2.887 which are similar to those of two Plasmodium spp. glycolytic enzymes lactate dehydrogenase and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase suggesting the essentiality of the protein for optimal parasite growth [62]. Plasmodium spp. obtain most of their metabolic energy from glycolysis which would explain the essentiality of the glycolytic enzymes [63, 64]. There is uncertainty about the role of the Plasmodium spp. electron transport chain and cytochrome c oxidase or complex IV in the metabolism of Plasmodium spp. [4]. What is known is that inhibitors of complex IV depolarize the membrane potential (Δψ) across the inner mitochondrial membrane and reduce oxygen consumption [65, 66]. Further studies of Plasmodium Cox11 will contribute to the understanding of Plasmodium copper metabolism and the assembly and metabolic role of Plasmodium spp. cytochrome c oxidase and the electron transport chain.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- Abu:

-

Alpha amino butyric acid

- ATOX-1:

-

Antioxidant Protein 1

- BCA:

-

Bicinchoninic acid

- CCS:

-

Copper Chaperone for Superoxide dismutase

- Cox:

-

Cytochrome c oxidase

- Ctr1:

-

Copper transporter 1

- ECL:

-

Enhanced chemiluminescence

- HRPO:

-

Horse radish peroxidase

- rMBP:

-

Recombinant maltose binding protein

- rMBPPfCox11Ct:

-

Recombinant maltose binding protein Plasmodium falciparum Cox11 carboxy-terminus

References

Nixon GL, Pidathala C, Shone AE, Antoine T, Fisher N, O’Neill PM, et al. Targeting the mitochondrial electron transport chain of Plasmodium falciparum: new strategies towards the development of improved antimalarials for the elimination era. Futur Med Chem. 2013;5:1573–91.

Hayward JA, van Dooren GG. Same same, but different: uncovering unique features of the mitochondrial respiratory chain of apicomplexans. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2019;232: 111204.

Aikawa M. The fine structure of the erythrocytic stages of three avian malarial parasites, Plasmodium fallax, P. lophurae, and P. cathemerium. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1966;15:449–71.

van Dooren GG, Stimmler LM, McFadden GI. Metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium mitochondrion. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2006;30:596–630.

Halliwell B, Gutteridge JM. Oxygen toxicity, oxygen radicals, transition metals and disease. Biochem J. 1984;219:1–14.

Choveaux DL, Przyborski JM, Goldring JD. A Plasmodium falciparum copper-binding membrane protein with copper transport motifs. Malar J. 2012;11:397.

Fairfield AS, Eaton JW, Meshnick SR. Superoxide dismutase and catalase in the murine malaria, Plasmodium berghei: content and subcellular distribution. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1986;250:526–9.

Rasoloson D, Shi L, Chong CR, Kafsack BF, Sullivan DJ. Copper pathways in Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes indicate an efflux role for the copper P-ATPase. Biochem J. 2004;381:803–11.

Robinson NJ, Winge DR. Copper metallochaperones. Annu Rev Biochem. 2010;79:537–62.

Kenthirapalan S, Waters AP, Matuschewski K, Kooij TW. Copper-transporting ATPase is important for malaria parasite fertility. Mol Microbiol. 2014;91:315–25.

Rosenberg E, Litus I, Schwarzfuchs N, Sinay R, Schlesinger P, Golenser J, et al. pfmdr2 confers heavy metal resistance to Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:27039–45.

Asahi H, Tolba ME, Tanabe M, Sugano S, Abe K, Kawamoto F. Perturbation of copper homeostasis is instrumental in early developmental arrest of intraerythrocytic Plasmodium falciparum. BMC Microbiol. 2014;14:167.

Krungkrai J. The multiple roles of the mitochondrion of the malarial parasite. Parasitology. 2004;129:511–24.

Cobine PA, Pierrel F, Bestwick ML, Winge DR. Mitochondrial matrix copper complex used in metallation of cytochrome oxidase and superoxide dismutase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36552–9.

Horng YC, Cobine PA, Maxfield AB, Carr HS, Winge DR. Specific copper transfer from the Cox17 metallochaperone to both Sco1 and Cox11 in the assembly of yeast cytochrome C oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:35334–40.

Choveaux DL, Krause RG, Przyborski JM, Goldring JD. Identification and initial characterisation of a Plasmodium falciparum Cox17 copper metallochaperone. Exp Parasitol. 2015;148:30–9.

Beers J, Glerum DM, Tzagoloff A. Purification, characterization, and localization of yeast Cox17p, a mitochondrial copper shuttle. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:33191–6.

Maxfield AB, Heaton DN, Winge DR. Cox17 is functional when tethered to the mitochondrial inner membrane. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:5072–80.

Cobine PA, Pierrel F, Winge DR. Copper trafficking to the mitochondrion and assembly of copper metalloenzymes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763:759–72.

Vest KE, Leary SC, Winge DR, Cobine PA. Copper import into the mitochondrial matrix in Saccharomyces cerevisiae is mediated by Pic2, a mitochondrial carrier family protein. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:23884–92.

Boulet A, Vest KE, Maynard MK, Gammon MG, Russell AC, Mathews AT, et al. The mammalian phosphate carrier SLC25A3 is a mitochondrial copper transporter required for cytochrome c oxidase biogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2018;293:1887–96.

Tzagoloff A, Capitanio N, Nobrega MP, Gatti D. Cytochrome oxidase assembly in yeast requires the product of COX11, a homolog of the P. denitrificans protein encoded by ORF3. EMBO J. 1990;9:2759–64.

Carr HS, George GN, Winge DR. Yeast Cox11, a protein essential for cytochrome c oxidase assembly, is a Cu(I)-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:31237–42.

Banci L, Bertini I, Cantini F, Ciofi-Baffoni S, Gonnelli L, Mangani S. Solution structure of Cox11, a novel type of beta-immunoglobulin-like fold involved in CuB site formation of cytochrome c oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:34833–9.

Hiser L, Di Valentin M, Hamer AG, Hosler JP. Cox11p is required for stable formation of the Cu(B) and magnesium centers of cytochrome c oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:619–23.

Radin I, Mansilla N, Rodel G, Steinebrunner I. The Arabidopsis COX11 homolog is essential for cytochrome c oxidase activity. Front Plant Sci. 2015;6:1091.

Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer EL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305:567–80.

Sievers F, Wilm A, Dineen D, Gibson TJ, Karplus K, Li W, et al. Fast, scalable generation of high-quality protein multiple sequence alignments using Clustal Omega. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:539.

Guex N, Peitsch MC. SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis. 1997;18:2714–23.

Ho SN, Hunt HD, Horton RM, Pullen JK, Pease LR. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–9.

Goldring JPD. Concentrating proteins by salt, polyethylene glycol, solvent, SDS precipitation, three-phase partitioning, dialysis, centrifugation, ultrafiltration, lyophilization, affinity chromatography, immunoprecipitation or increased temperature for protein isolation, drug interaction, and proteomic and peptidomic evaluation. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1855:41–59.

Goldring JP. Methods to concentrate proteins for protein isolation, proteomic, and peptidomic evaluation. Methods Mol Biol. 2015;1314:5–18.

Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein–dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–54.

Goldring JPD. Measuring protein concentration with absorbance, Lowry, Bradford Coomassie Blue, or the Smith bicinchoninic acid assay before electrophoresis. Methods Mol Biol. 2019;1855:31–9.

Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5.

Isah MB, Goldring JPD, Coetzer THT. Expression and copper binding properties of the N-terminal domain of copper P-type ATPases of African trypanosomes. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2020;235: 111245.

Brenner AJ, Harris ED. A quantitative test for copper using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1995;226:80–4.

Jiang J, Nadas IA, Kim MA, Franz KJ. A Mets motif peptide found in copper transport proteins selectively binds Cu(I) with methionine-only coordination. Inorg Chem. 2005;44:9787–94.

Niesen FH, Berglund H, Vedadi M. The use of differential scanning fluorimetry to detect ligand interactions that promote protein stability. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:2212–21.

Carmenes R, Freije J, Molina M, Martin J. Predict7, a program for protein structure prediction. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1989;159:687–93.

Kitagawa T, Aikawa T. Enzyme coupled immunoassay of insulin using a novel coupling reagent. J Biochem. 1976;79:233–6.

Goldring J, Coetzer TH. Isolation of chicken immunoglobulins (IgY) from egg yolk. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2003;31:185–7.

Goldring JP, Brake DA, Cavacini LA, Long CA, Weidanz WP. Cloned T cells provide help for malaria-specific polyclonal antibody responses. Eur J Immunol. 1989;19:559–61.

Warhurst DC, Williams JE. ACP Broadsheet no 148. July 1996. Laboratory diagnosis of malaria. J Clin Pathol. 1996;49:533–8.

Towbin H, Staehelin T, Gordon J. Electrophoretic transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide gels to nitrocellulose sheets: procedure and some applications. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:4350–4.

Aurrecoechea C, Brestelli J, Brunk BP, Dommer J, Fischer S, Gajria B, et al. PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D539-43.

Plasmodium Genomics Resource www.plasmodb.org

Banting GS, Glerum DM. Mutational analysis of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae cytochrome c oxidase assembly protein Cox11p. Eukaryot Cell. 2006;5:568–78.

Le Roch KG, Zhou Y, Blair PL, Grainger M, Moch JK, Haynes JD, et al. Discovery of gene function by expression profiling of the malaria parasite life cycle. Science. 2003;301:1503–8.

Toenhake CG, Fraschka SA, Vijayabaskar MS, Westhead DR, van Heeringen SJ, Bártfai R. Chromatin accessibility-based characterization of the gene regulatory network underlying Plasmodium falciparum blood-stage development. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:557-569.e9.

Heckman KL, Pease LR. Gene splicing and mutagenesis by PCR-driven overlap extension. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:924–32.

Jimenez I, Speisky H. Effects of copper ions on the free radical-scavenging properties of reduced gluthathione: implications of a complex formation. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 2000;14:161–7.

Pantoliano MW, Petrella EC, Kwasnoski JD, Lobanov VS, Myslik J, Graf E, et al. High-density miniaturized thermal shift assays as a general strategy for drug discovery. J Biomol Screen. 2001;6:429–40.

Krause RGE, Goldring JPD. Phosphoethanolamine-N-methyltransferase is a potential biomarker for the diagnosis of P. knowlesi and P. falciparum malaria. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0193833.

Krause RGE, Hurdayal R, Choveaux D, Przyborski JM, Coetzer THT, Goldring JPD. Plasmodium glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase: a potential malaria diagnostic target. Exp Parasitol. 2017;179:7–19.

Carr HS, Maxfield AB, Horng YC, Winge DR. Functional analysis of the domains in Cox11. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:22664–9.

Leary SC, Kaufman BA, Pellecchia G, Guercin GH, Mattman A, Jaksch M, et al. Human SCO1 and SCO2 have independent, cooperative functions in copper delivery to cytochrome c oxidase. Hum Mol Genet. 2004;13:1839–48.

Khalimonchuk O, Ostermann K, Rodel G. Evidence for the association of yeast mitochondrial ribosomes with Cox11p, a protein required for the Cu(B) site formation of cytochrome c oxidase. Curr Genet. 2005;47:223–33.

Thompson AK, Smith D, Gray J, Carr HS, Liu A, Winge DR, et al. Mutagenic analysis of Cox11 of Rhodobacter sphaeroides: insights into the assembly of Cu(B) of cytochrome c oxidase. Biochemistry. 2010;49:5651–61.

Bode M, Woellhaf MW, Bohnert M, van der Laan M, Sommer F, Jung M, et al. Redox-regulated dynamic interplay between Cox19 and the copper-binding protein Cox11 in the intermembrane space of mitochondria facilitates biogenesis of cytochrome c oxidase. Mol Biol Cell. 2015;26:2385–401.

Bratton MR, Hiser L, Antholine WE, Hoganson C, Hosler JP. Identification of the structural subunits required for formation of the metal centers in subunit I of cytochrome c oxidase of Rhodobacter sphaeroides. Biochemistry. 2000;39:12989–95.

Zhang M, Wang C, Otto TD, Oberstaller J, Liao X, Adapa SR, et al. Uncovering the essential genes of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum by saturation mutagenesis. Science. 2018;360:eaap7847.

Roth EF Jr, Calvin MC, Max-Audit I, Rosa J, Rosa R. The enzymes of the glycolytic pathway in erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium falciparum malaria parasites. Blood. 1988;72:1922–5.

Sherman I. Carbohydrate metabolism of asexual stages. In: Sherman I, editor. Malaria: parasite biology, pathogenesis and protection. Washington DC: American Society of Microbiology; 1998.

Srivastava P, Arif AJ, Singh C, Pandey VC. N-acetyl penicillamine a protector of Plasmodium berghei induced stress organ injury in mice. Pharmacol Res. 1997;36:305–7.

Uyemura SA, Luo S, Moreno SN, Docampo R. Oxidative phosphorylation, Ca(2+) transport, and fatty acid-induced uncoupling in malaria parasites mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9709–15.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Theresa Coetzer for reading the manuscript.

Funding

We would like to thank the South African National Research Foundation and the University of KwaZulu-Natal Research Incentive Fund for financial support. A. A. Salman thanks the Ahmadu Bello University, Nigeria, for a study fellowship.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DG conceived the study and obtained the funding, AS conducted the experiments. AS and DG performed the analysis. DG and AS prepared the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures involving animals were approved by the University of KwaZulu-Natal, Animal Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 0045/15/Animal).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Salman, A.A., Goldring, J.P.D. Expression and copper binding characteristics of Plasmodium falciparum cytochrome c oxidase assembly factor 11, Cox11. Malar J 21, 173 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04188-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-022-04188-5