Abstract

Background

There have been an increasing number of imported cases of malaria in Hubei Province in recent years. In particular, the number of cases of Plasmodium ovale spp. and Plasmodium malariae significantly increased, which resulted in increased risks during the malaria elimination phase. The purpose of this study was to acquire a better understanding of the epidemiological characteristics of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae imported to Hubei Province, China, so as to improve case management.

Methods

Data on all malaria cases from January 2014 to December 2018 in Hubei Province were extracted from the China national diseases surveillance information system (CNDSIS). This descriptive study was conducted to analyse the prevalence trends, latency periods, interval from onset of illness to diagnosis, and misdiagnosis of cases of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae malaria.

Results

During this period, 634 imported malaria cases were reported, of which 87 P. ovale spp. (61 P. ovale curtisi and 26 P. ovale wallikeri) and 18 P. malariae cases were confirmed. The latency periods of P. ovale spp., P. malariae, Plasmodium vivax, and Plasmodium falciparum differed significantly, whereas those of P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri were no significant difference. The proportion of correct diagnosis of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae malaria cases were 48.3% and 44.4%, respectively, in the hospital or lower-level Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). In the Provincial Reference Laboratory, the sensitivity of microscopy and rapid diagnostic tests was 94.3% and 70.1%, respectively, for detecting P. ovale spp., and 88.9% and 38.9%, respectively, for detecting P. malariae. Overall, 97.7% (85/87) of P. ovale spp. cases and 94.4% (17/18) of P. malariae cases originated from Africa.

Conclusion

The increase in the number of imported P. ovale spp. and P. malariae cases, long latency periods, and misdiagnosis pose a challenge to this region. Therefore, more attention should be paid to surveillance of imported cases of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae infection to reduce the burden of public health and potential risk of malaria.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria is one of the major global public health threats and causes substantial morbidity, mortality, and human suffering. In 2017, an estimated 219 million malaria cases occurred worldwide, with 435,000 deaths reported [1]. In humans, malaria is caused by five Plasmodium species (Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium vivax, Plasmodium malariae, Plasmodium ovale spp., and Plasmodium knowlesi) [2,3,4,5]. However, less emphasis is placed on malaria caused by P. ovale spp. and P. malariae compared with P. falciparum and P. vivax, since malaria caused by P. ovale spp. and P. malariae has a more benign clinical course than that caused by P. falciparum. Therefore, malaria caused by P. ovale spp. and P. malariae have been neglected and are understudied [6,7,8].

In recent years, the number of imported P. ovale spp. and P. malariae malaria cases has increased yearly in China [9, 10]. However, no local P. ovale spp. malaria cases have ever been reported in Hubei Province, and no local P. malariae malaria cases have been detected since 1963 [11]. Since 2013, no indigenous malaria cases have been reported in Hubei Province; furthermore, imported malaria cases, particularly those of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae, significantly increased, which resulted in increased risks during the malaria elimination phase [12, 13]. Patients infected with P. ovale spp. and P. malariae often had longer latency periods than those infected with P. falciparum, and they may present with malaria symptoms months or even years after returning from an endemic region [14, 15]. Therefore, accurate and prompt identification of malaria species is required for suitable use of anti-malarial drugs to reduce the burden of public health and potential risk of malaria.

In recent years, two sympatric species of P. ovale spp. have been distinguished: P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri [5]. The morphology of these two sympatric species of P. ovale spp. was identical on microscopy, but the two can be differentiated by genetic typing [16, 17]. To date, however, there have been few epidemiological studies conducted of P. ovale spp. in Hubei. In light of the epidemiology of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae, a comprehensive analysis was required to explore the changing epidemiology and challenges encountered in Hubei with respect to malaria elimination. Thus, in this study, the data were obtained from the China National Disease Surveillance Information System (CNDSIS) during 2014–2018. This descriptive study was conducted to analyse the prevalence trends, latency periods, interval from onset of illness to diagnosis, and misdiagnosis of cases of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae malaria. The evidence of this study will help in providing a reference for preventing and managing imported P. ovale spp. and P. malariae malaria cases in Hubei Province.

Methods

Data collection

Data on malaria cases in Hubei Province from 2014 to 2018 were obtained from (CNDSIS). The following details of patients with malaria were extracted: gender, age, occupation, admission dates, symptom onset time, time of diagnosis, laboratory-confirmed results, travel history.

Laboratory examinations

All cases were initially diagnosed using thick and thin blood film microscopy at hospitals or low-level Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Thereafter, all results were then sent to the Hubei Provincial Reference Laboratory for Malaria Diagnosis. All cases were confirmed by the Provincial Reference Laboratory for using thick and thin blood film microscopy, malaria rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs), and nested polymerase chain reaction (nested PCR). Thick and thin blood films were stained using a standard technique with Giemsa solution for 35 min; they were then examined by trained microscopists to diagnose and identify malaria species. Next, 5 μl of whole blood of each patient was analysed using the Ag Pf/Pan RDTs (Guangzhou Wondfo Biotech Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, China) following the manufacturer’s protocol. As nested PCR is more sensitive and specific in determining the malaria parasite species [18, 19]; for detecting the Plasmodium species and two sympatric subspecies of P. ovale spp. at the molecular level, nested PCR was performed by amplifying the 18SSU rRNA gene of the malaria parasite. The nested PCR protocol was followed: DNA isolation was extracted by using the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN®) from the blood sample following the protocol. The first reaction of DNA amplification was performed by using rPLU5 and rPLU6 primers (Thermos®) [20]. The PCR solution had a total volume of 20 μl, comprising 3 μl of DNA solution, 0.2 μl of Taq DNA polymerase (Takara®), 1.1 μl of each primers (10 μmol/l), 1.6 μl of dNTPs (2.5 mmol/l), 4.0 μl of 5× Buffer and 9.0 μl of ddH2O. For the second reaction, there are five pairs of primers were used: rVIV1/rVIV2 (P. vivax), rFAL1/rFAL2 (P. falciparum), rMAL1/rMAL2 (P. malariae), rOVA1/rOVA2 (P. ovale curtisi) and rOVA1v/rOVA2v (P. ovale wallikeri). These were used to determine the Plasmodium species [17, 20]. The PCR solution had a total volume of 20 μl, comprising 2 μl of PCR product of the first reaction as the template, 10 μl of 2× DreamTaq PCR Master Mix (Fermentas®), 1.0 μl of each primers (10 μmol/l), add enough ddH2O to make up the volume to 20 μl. The incubation conditions of the two PCR rounds were as follows: 3 min at 94 °C; followed by 35 cycles of 30 s at 94 °C, 30 s at 58 °C, 1 min at 72 °C, and a final extension for 5 min at 72 °C. The PCR products of the second reaction were run on standard 1.5% agarose gels.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software version 16.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Owing to the lack of the exact date of malaria infection, the date of arrival in China was used as the date of malaria infection. The latency period, in days, was calculated for each case of malaria by subtracting the date of arrival in China from the date of symptom onset. The confirmed diagnosis interval in days was calculated from the onset of symptoms to laboratory confirmation in provincial CDC. The latency period and confirmed diagnosis interval were calculated and compared for all malaria cases except mixed Plasmodium infections. Because the latency periods and interval from the onset of illness to diagnosis had non-normal distribution, the differences were compared using Kruskal–Wallis H tests and two independent sample Mann–Whitney U tests, with p-values < 0.05 considered statistically significant. The ArcGIS software version 10.0 (ESRI Inc., Redlands, CA, USA) was used to produce figures of the geographic distribution of the countries of origin of the imported P. ovale spp. and P. malariae cases.

Results

Prevalence of imported P. ovale spp. and P. malariae

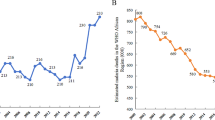

During 2014–2018, a total of 634 imported malaria cases were reported in Hubei Province (Table 1). P. falciparum (440), P. vivax (84), P. ovale spp. (87), P. malariae (18) and mixed infection (3) accounted for 69.4%, 13.2%, 13.7%, 2.8%, and 0.5% of all reported cases, respectively. The P. ovale spp. incidence ranged from 11 to 24 cases per year and that of P. malariae from 0 to 7 cases per year for the period 2014–2018. Among the 87 patients infected P. ovale spp. and 18 patients infected with P. malariae, there was only one patient infected with P. ovale spp., who was a Nigerian, the rest were all Chinese who worked in a malaria-endemic countries as migrant workers.

For all 86 Chinese P. ovale spp. patients, the median and interquartile range of the duration of stay overseas was 345 days (167–523). For all P. malariae patients, the median and interquartile range of duration of stay overseas was 360.5 days (222.5–667.8). In total, 87 P. ovale spp. cases, including 61 P. ovale curtisi and 26 P. ovale wallikeri (the first P. ovale wallikeri case was discovered in 2015) (Fig. 1), and 18 P. malariae cases were confirmed by nested PCR.

Latency period between arrival in China and illness onset

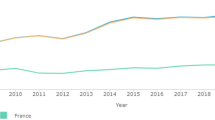

The latency periods from returning to the country to the onset of symptoms are shown in Fig. 2. The median latency period (interquartile range, IQR) of P. ovale spp. was 47 (20.5–165.5) days, P. malariae was 20.5 (2.5–54.25) days, P. vivax was 37 (9.75–89) days, and P. falciparum was 6 (2–10) days. There was a significant difference in latency periods of four Plasmodium species (H = 176.93, p < 0.001). The median (IQR) latency periods of P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri were 62 (24–195) days and 33 (14.25–129) days, respectively. There was no significant difference in the latency periods between P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri (Z = − 1.308, p = 0.191).

Latency periods for imported malaria cases in Hubei Province, 2014–2018. a Latency in days of cases caused by four Plasmodium species. b Latency in days of P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri cases. The box plots show the latency period between arrival in China and illness onset. The midline of each box plot is the median, with the edges of the box representing the interquartile interval. Whiskers delineate the 5th and 95th percentiles. The black circles represent outliers of latency days. The asterisk represents the extreme of days elapsed between arrival in China and illness onset

Interval from onset of illness to diagnosis

The intervals from onset of the illness to diagnosis are shown in Fig. 3. The median interval from the onset of illness to diagnosis (IQR) of P. ovale spp. was 9 (4–43.5) days, P. malariae was 13.5 (7.5–77.25) days, P. vivax was 4 (2–9) days, and P. falciparum was 3 (1–5) days. There was a significant difference in the interval from the onset of illness to diagnosis among four Plasmodium species (H = 48.168, p < 0.001). The median intervals from the onset of illness to diagnosis (IQR) of P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri were 7 (3–34) days and 15 (4.25–62.75) days, respectively. There was no significant difference in the time from the onset of illness to diagnosis between P. o. curtisi and P. o. wallikeri (Z = 1.611, p = 0.107).

Interval from the onset of illness to diagnosis for imported malaria cases in Hubei Province, 2014–2018. a The interval from the onset of illness to diagnosis of malaria caused by four Plasmodium species. b The interval from the onset of illness to diagnosis of P. ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri cases. The midline of each box plot is the median, with the edges of the box representing the interquartile interval. Whiskers delineate the 5th and 95th percentiles. The black circles represent the outliers of days elapsed between the interval from the onset of illness to diagnosis. The asterisk represents the extreme of days elapsed between the interval from the onset of illness to diagnosis

Misdiagnosis of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae malaria cases

The misdiagnosis of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae is shown in Table 2. The initial malaria diagnosis was made via thick and thin blood film examination at hospitals or the lower-level CDC (county and city). Of 87 P. ovale spp. cases, only 42 had an accurate initial diagnosis, accounting for 48.3% of the P. ovale spp. cases. Similarly, of 18 P. malariae cases, only eight had an accurate initial diagnosis, accounting for 44.4% of all P. malariae cases.

The sensitivity of microscopy and RDTs for diagnosing P. ovale spp. and P. malariae are shown in Table 3. In the Hubei Provincial Reference Laboratory for Malaria Diagnosis, 87 P. ovale spp. cases and 18 P. malariae cases were diagnosed by nested PCR. Of the 82 P. ovale spp. cases, 5 were misdiagnosed as P. vivax on microscopy. Of the 18 P. malariae cases, 2 were misdiagnosed as P. vivax on microscopy. RDT sensitivity of infections resulting from P. ovale spp. and P. malariae were 70.1% and 38.9%, respectively.

Origin of imported P. ovale spp. and P. malariae cases

During 2014–2018, the 87 imported P. ovale spp. cases and 18 imported P. malariae cases were acquired from 24 countries located in Africa, Asia, and Oceania. Overall, 97.7% (85/87) of P. ovale spp. cases and 94.4% (17/18) of P. malariae cases were from Africa, with only two P. ovale spp. cases from Asian countries and one P. malariae case from Oceania (Papua New Guinea). The countries of origin of cases imported from African countries are shown in Fig. 4.

98.4% (60/61) of P. o. curtisi and 96.2%(25/26) of P. o. wallikeri were from Africa. P. o. curtisi cases were mainly imported from Democratic Republic of Congo (9, 14.8%), Nigeria (7, 11.5%), Equatorial Guinea (6, 9.8%), Angola (5, 8.2%), and Congo (Brazzaville) (5, 8.2%), and one P. o. curtisi case from Turkey. P. o. wallikeri cases were mainly imported from Democratic Republic of Congo (4, 15.4%), Cameroon (4, 15.4%), Nigeria (4, 15.4%), Angola (3, 11.5%), Congo (Brazzaville) (3, 11.5%), and Uganda (3, 11.5%), and one P. o. wallikeri case from Bangladesh. Plasmodium malariae was mainly imported from Angola (3, 16.7%), Congo (Brazzaville) (3, 16. 7%), Cameroon (2, 11.1%), Liberia (2, 11.1%), and Nigeria (2, 11.1%).

Discussion

Hubei Province has achieved remarkable success in controlling the local malaria situation; however, the number of imported malaria cases has increased. Although the majority of imported malaria cases were associated with P. falciparum, the number of patients with imported P. ovale spp. and P. malariae significantly increased, especially the number of patients with imported P. ovale spp. was more than that with P. vivax from 2014 to 2018. The increase in the number of imported P. ovale spp. and P. malariae cases presented a new challenge for achieving the long-term goal of malaria elimination [21].

In this study, there was a significant difference in the latency period of the four Plasmodium species. However, the difference between the two sympatric species of P. ovale spp. was not significant in this study, which is similar to the finding of Cao et al. [22] and Rojo-Marcos et al. [23]. In this study, the longest latency periods of P. o. curtisi and P. o.e wallikeri were 733 and 793 days, respectively. The longest latency periods of P. o. curtisi in the study by Nolder et al. [15] and Zhou et al. [24] were 1083 and 1265 days, respectively. Long latency periods present considerable difficulties for malaria diagnosis and its appropriate treatment [25]. The intervals from the onset of illness to diagnosis of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae were longer than those of P. vivax and P. falciparum. Because of the rare occurrence of indigenous P. ovale spp. and P. malariae malaria in Hubei Province, these Plasmodium species have been largely neglected. Moreover, some patients did not visit the hospital immediately because of their mild symptoms. However, delayed diagnosis of these two Plasmodium species will lead to worse clinical outcomes [26].

In this study, the rates of correct diagnosis of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae malaria cases were 48.3% and 44.4%, respectively, in hospitals or lower-level CDC. The misdiagnosis were driven by two factors, one was the health technicians’ lack of knowledge about these two species of malaria [27], and the other was morphological changes associated with low levels of parasitaemia and use of non-standard medications [28,29,30,31]. Therefore, training on using microscopy for initial diagnosis of malaria at hospitals and lower-level CDC should be strengthened. Periodic refresher training has helped maintain microscopy capabilities for accurate detection and diagnosis of Plasmodium parasites at all levels of CDC and hospitals; furthermore, a standard malaria testing procedure should be established at a lower level [32].

Identification of Plasmodium species is one of the important steps in malaria elimination. Common methods for the diagnosis of malaria include thick and thin blood film microscopy, RDTs, and PCR. The current gold standard for malaria diagnosis remains microscopy. However, this technique needs considerable training and experience. It was difficult to identify P. ovale spp. by only microscopic examination, because the morphology of this species is similar to that of P. vivax [29]. This study showed that five P. ovale spp. isolates were misidentified as P. vivax in microscopic examination in the provincial reference laboratory. PCR has higher sensitivity than microscopy in diagnosing P. ovale spp. and P. malariae infections [28, 33] which can be used to validate the laboratory diagnosis of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae infections [34]. RDTs provide access to accurate malaria diagnosis in many areas [35], because it is easy to use and require no specific equipment [36]. In this study, RDT sensitivity of infections resulting from P. ovale spp. was 70.1% which was suboptimal [37]. Hence, suggested that in hospitals or lower-level CDC, RDTs could be used to be a complementary part to microscopic examination of P. ovale spp. infections.

In this study, P. ovale spp. and P. malariae were acquired from sub-Saharan Africa. Collins and Jeffery [6] observed that the natural distribution of P. ovale spp. cases was in sub-Saharan Africa and some western Pacific islands. Both species of P. ovale spp. are considered to be sympatric throughout their geographical distribution [2]. However, P. malariae is mainly found in sub-Saharan Africa and southwest Pacific [7]. With the steadily increasing numbers of individuals working and travelling abroad to malaria-endemic Africa, malaria control in Hubei Province will likely remain an important challenge.

This study had some limitations. First, the database relied on passive case detection and inevitably could underestimate the numbers of imported malaria cases. Second, owing to the lack of an exact date of infection, the latency period was calculated using the arrival dates of patients when they returned to China, which means that the latency period of each case used in the study is a minimum estimate; the date of symptom onset relied on patient reporting, which is may be subject to recall bias and may therefore affect the confirmed diagnosis interval. Third, the small number of patients limited the statistical power to show differences among infections with different Plasmodium species.

Conclusions

Imported malaria cases are the primary challenge for Hubei Province in achieving the long-term goal of malaria elimination. The study results demonstrated that the incidence of P. ovale spp. and P. malariae cases increased significantly. It also indicated the number of P. ovale spp. cases overtook that of P. vivax cases in Hubei Province. Nevertheless, these two species were most often misidentified or missed at hospitals or low-level CDC. Thus, suggested that more attention be paid to surveillance of imported P. ovale spp. and P. malariae cases to reduce the burden of public health and potential risk of malaria in China.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

WHO. World malaria report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Sutherland CJ, Tanomsing N, Nolder D, Oguike M, Jennison C, Pukrittayakamee S, et al. Two non recombining sympatric forms of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium ovale occur globally. J Infect Dis. 2010;201:1544–50.

Jongwutiwes S, Buppan P, Kosuvin R, Seethamchai S, Pattanawong U, Sirichaisinthop J, et al. Plasmodium knowlesi malaria in humans and macaques, Thailand. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:1799–806.

Kavunga-Membo H, Ilombe G, Masumu J, Matangila J, Imponge J, Manzambi E, et al. Molecular identification of Plasmodium species in symptomatic children of Democratic Republic of Congo. Malar J. 2018;17:334.

Fuehrer HP, Habler VE, Fally MA, Harl J, Starzengruber P, Swoboda P, et al. Plasmodium ovale in Bangladesh: genetic diversity and the first known evidence of the sympatric distribution of Plasmodium ovale curtisi and Plasmodium ovale wallikeri in southern Asia. Int J Parasitol. 2012;42:693–9.

Collins WE, Jeffery GM. Plasmodium ovale: parasite and disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:570–81.

Collins WE, Jeffery GM. Plasmodium malariae: parasite and disease. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20:579–92.

Mueller I, Zimmerman PA, Reeder JC. Plasmodium malariae and Plasmodium ovale—the “bashful” malaria parasites. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:278–83.

Feng J, Xiao HH, Xia ZG, Zhang L, Xiao N. Analysis of malaria epidemiological characteristics in the People’s Republic of China, 2004–2013. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:293–9.

Zhou S, Li ZJ, Cotter C, Zheng CJ, Zhang Q, Li HZ, et al. Trends of imported malaria in China 2010–2014: analysis of surveillance data. Malar J. 2016;15:39.

Huang GQ, Yan BW, Yuan FY, Pei SJ. Thirty-year experience of malaria control in Hubei Province. J Publ Health Prev Med. 2004;15:66–8 (in Chinese).

Xia J, Huang XB, Sun LC, Zhu H, Lin W, Dong XR, et al. Epidemiological characteristics of malaria from control to elimination in Hubei Province, China, 2005–2016. Malar J. 2018;17:81.

Xia J, Zhang HX, Liu S, Wu DG, Zhang J, Sun LC, et al. Epidemiological analysis of malaria prevalence in Hubei Province from 2015 to 2018. Chin J Parasitol Dis. 2020;38:1–7 (in Chinese).

Teo BH, Lansdell P, Smith V, Blaze M, Nolder D, Beshir KB, et al. Delayed onset of symptoms and atovaquone-proguanil chemoprophylaxis breakthrough by Plasmodium malariae in the absence of mutation at Codon 268 of pmcytb. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2015;9:e0004068.

Nolder D, Oguike MC, Maxwell-Scott H, Niyazi HA, Smith V, Chiodini PL, et al. An observational study of malaria in British travellers: Plasmodium ovale wallikeri and Plasmodium ovale curtisi differ significantly in the duration of latency. BMJ Open. 2013;3:e002711.

Win TT, Jalloh A, Tantular IS, Tsuboi T, Ferreira MU, Kimura M, et al. Molecular analysis of Plasmodium ovale variants. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1235–40.

Calderaro A, Piccolo G, Perandin F, Gorrini C, Peruzzi S, Zuelli C, et al. Genetic polymorphisms influence Plasmodium ovale PCR detection accuracy. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1624–7.

Li PP, Zhao ZJ, Wang Y, Xing H, Daniel MP, Yang ZQ, et al. Nested PCR detection of malaria directly using blood filter paper samples from epidemiological surveys. Malar J. 2014;13:175.

Nebiye YD, Fadile YZ, Adnan S. Detection of Plasmodium using filter paper and nested PCR for patients with malaria in Sanliurfa, in Turkey. Malar J. 2016;15:299.

Snounou G, Viriyakoso LS, Zhu XP, et al. High sensitivity of detection of human malaria parasites by the use of nested polymerase chain reaction. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;61:315–20.

Yan H, Xia ZG, Feng J, Xiao HH, Yin JH, Li M. Analysis of imported malariae malaria and ovale malaria in China during 2011–2013. Int J Med Parasit Dis. 2015;42(14–17):21 (in Chinese).

Cao YY, Wang WM, Liu YB, Cotter C, Zhou HY, Zhu GD, et al. The increasing importance of Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae in a malaria elimination setting: an observational study of imported cases in Jiangsu Province, China, 2011–2014. Malar J. 2016;15:459.

Rojo-Marcos G, Rubio-Muñoz JM, Ramírez-Olivencia G, García-Bujalance S, Elcuaz-Romano R, Díaz-Menéndez M, et al. Comparison of imported Plasmodium ovale curtisi and P. ovale wallikeri infections among patients in Spain, 2005–2011. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:409–16.

Zhou RM, Li SH, Zhao YL, Yang CY, Liu Y, Qian D, et al. Characterization of Plasmodium ovale spp. imported from Africa to Henan Province, China. Sci Rep. 2019;9:2191.

Bottieau E, Clerinx J, Van Den Enden E, Van Esbroeck M, Colebunders R, Van Gompel A, et al. Imported non-Plasmodium falciparum malaria: a five-year prospective study in a European referral center. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75:133–8.

Kain KC, Harrington MA, Tennyson S, Keystone JS. Imported malaria: prospective analysis of problems in diagnosis and management. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:142–9.

Wu DN, Dong XR, Xia J, Zhang HX, Sun LC, Li KJ, et al. Analysis of the examination of city/prefecture-level malaria laboratories in Hubei Province. China Trop Med. 2018;18:1202–6 (in Chinese).

Sun H, Li J, Xu C, Xiao T, Wang LJ, Kong XL, et al. Increasing number of imported Plasmodium ovale wallikeri malaria in Shandong Province, China, 2015–2017. Acta Trop. 2019;191:248–51.

Roucher C, Rogier C, Sokhna C, Tall A, Trape JF. A 20-year longitudinal study of Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae prevalence and morbidity in a West African population. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e87169.

Doderer-Lang C, Atchade PS, Meckert L, Haar E, Perrotey S, Filisetti D, et al. The ears of the African elephant: unexpected high seroprevalence of Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae in healthy populations in Western Africa. Malar J. 2014;13:240.

Koita OA, Sangaré L, Sango HA, Dao S, Keita N, Maiga M, et al. Effect of seasonality and ecological factors on the prevalence of the four malaria parasite species in northern Mali. J Trop Med. 2012;2012:367160.

Ding GS, Zhu GD, Cao CQ, Miao P, Cao YY, Wang WM, et al. The challenge of maintaining microscopist capacity at basic levels for malaria elimination in Jiangsu Province, China. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:489.

Snounou G, Viriyakosol S, Jarra W, Thaithong S, Brown KN. Identification of the four human malaria parasite species in field samples by the polymerase chain reaction and detection of a high prevalence of mixed infections. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;58:283–92.

Sitali L, Miller JM, Mwenda MC, Bridges DJ, Hawela MB, Hamainza B, et al. Distribution of Plasmodium species and assessment of performance of diagnostic tools used during a malaria survey in Southern and Western Provinces of Zambia. Malar J. 2019;18:130.

WHO. Guidelines for the treatment of malaria. 2nd ed. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010.

Tang JX, Tang F, Zhu HR, Lu F, Xu S, Cao YY, et al. Assessment of false-negative rates of lactate dehydrogenase-based malaria rapid diagnostic tests for Plasmodium ovale detection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13:e0007254.

Yerlikaya S, Campillo A, Gonzalez IJ. A systematic review: performance of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of Plasmodium knowlesi, Plasmodium malariae, and Plasmodium ovale monoinfections in human blood. J Infect Dis. 2018;218:265–76.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the staff of the hospitals and disease control and prevention in Hubei Province.

Funding

This study was funded by the Project of Disease Control and Prevention of the Hubei Provincial Health and Family Planning Commission (Grant No. WJ2016J-037).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JX, DNW, SL and HXZ designed study; JX contributed to the data analysis and edited the manuscript; DNW performed the laboratory studies and drafted the manuscript; LCS and HZ participated in the sample collection; JZ and WL were responsible for data collection; KJL and LW provided the administrative coordination; SL and HXZ provided guidance and coordination. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Hubei Province Center for Disease Control and Prevention. As the study was based on a retrospective review of disease notification data, informed consent was waived.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xia, J., Wu, D., Sun, L. et al. Characteristics of imported Plasmodium ovale spp. and Plasmodium malariae in Hubei Province, China, 2014–2018. Malar J 19, 264 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-020-03337-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-020-03337-y