Abstract

Background

Swaziland aims to eliminate malaria by 2020. However, imported cases from neighbouring endemic countries continue to sustain local parasite reservoirs and initiate transmission. As certain weather and climatic conditions may trigger or intensify malaria outbreaks, identification of areas prone to these conditions may aid decision-makers in deploying targeted malaria interventions more effectively.

Methods

Malaria case-surveillance data for Swaziland were provided by Swaziland’s National Malaria Control Programme. Climate data were derived from local weather stations and remote sensing images. Climate parameters and malaria cases between 2001 and 2015 were then analysed using seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average models and distributed lag non-linear models (DLNM).

Results

The incidence of malaria in Swaziland increased between 2005 and 2010, especially in the Lubombo and Hhohho regions. A time-series analysis indicated that warmer temperatures and higher precipitation in the Lubombo and Hhohho administrative regions are conducive to malaria transmission. DLNM showed that the risk of malaria increased in Lubombo when the maximum temperature was above 30 °C or monthly precipitation was above 5 in. In Hhohho, the minimum temperature remaining above 15 °C or precipitation being greater than 10 in. might be associated with malaria transmission.

Conclusions

This study provides a preliminary assessment of the impact of short-term climate variations on malaria transmission in Swaziland. The geographic separation of imported and locally acquired malaria, as well as population behaviour, highlight the varying modes of transmission, part of which may be relevant to climate conditions. Thus, the impact of changing climate conditions should be noted as Swaziland moves toward malaria elimination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Thanks to a long-term commitment and successfully deployed malaria control interventions, Swaziland is now aiming to eliminate malaria by 2020. If achieved, it would be the first country in sub-Saharan Africa to meet this ambitious goal [1,2,3]. Swaziland’s malaria burden is primarily caused by Plasmodium falciparum, which is predominately transmitted by the Anopheles arabiensis [4]. Swaziland’s combination of confirmatory diagnosis, prompt and efficacious treatment, targeted vector control, health promotion, and active surveillance has been critical in reducing the malaria burden to low levels [1]. With low levels of local transmission, controlling the import of malaria from high-endemic neighbouring countries has become increasingly important [5, 6]. Thus, significant resources have been in place since 2010 to rapidly detect and treat all cases, as well as to investigate people they have been in close contact with, in order to limit additional transmission [5]. The National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) of Swaziland has been initiating active investigations to follow up all confirmed cases at the household level since 2010. Imported and locally acquired cases can be classified according to travel history, either outside or within Swaziland. Originally, a case was deemed imported if the patient reported having traveled within the past 2 weeks, although this was later increased to 4 weeks in 2012 and to 8 weeks in 2013. Patients who did not report having traveled are deemed to have acquired malaria locally [7].

Since climatic conditions drive parasite and mosquito development, feeding frequency, and disease transmission, short-term climate variations (e.g., temperature, precipitation, and humidity) or irregular climatic phenomena (e.g., El Niño Southern Oscillation) may also be important factors in malaria transmission and the success of elimination programmes in previously unforeseen ways [8, 9]. Multiple studies have been conducted in malaria-endemic areas to investigate the association between climatic variations and malaria epidemics that might be associated with recent climate change [10,11,12]. For instance, regional climatic indices such as the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) or the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) have been linked to malaria transmission in Kenya, Ethiopia, and South Africa [13,14,15,16,17]. However, the impact of climate conditions on malaria transmission in Swaziland is poorly documented. Using the random forest regression tree approach to generate malaria risk maps of Swaziland in 2011 based on various environmental variables, a study has shown that warmer temperatures, lower rainfall, lower elevation, and close proximity to water contribute to a higher risk of malaria during high- and low-transmission seasons [18]. However, the study only evaluated the environmental influences over a very short period of time. Furthermore, it is possible that certain areas in Swaziland are more vulnerable than others to climate conditions that promote local transmission. Indeed, climatic conditions vary widely in Swaziland despite its relatively small size, and range from humid and temperate in the Highveld region to semi-arid and warm in the Lowveld region [1]. Hence, an analysis of climate conditions and their impact on transmission risk in Swaziland is necessary to reinforce long-term efforts to eliminate malaria and to support the establishment of a malaria early warning system in outbreak-prone Swaziland. The identification of areas or populations at risk of transmission due to climate variations could also enable the delivery of timely control interventions. Therefore, the specific aims of this study were to assess the impact of climatic variations on malaria transmission, and identify specific areas vulnerable to climate conditions that promote transmission in Swaziland.

Methods

Malaria incidence

Malaria case and population data provided by the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP) for 1985–2015 show that annual malaria incidence sharply decreased after 1995 following the successful application of control measures (Additional file 1).

The key intervention strategy in Swaziland is integrated vector management (IVM), which combines both indoor residual spraying (IRS) and long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLIN) to interrupt malaria transmission [1, 19]. Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) recommended by the WHO is used for treating malaria patients because a high level of chloroquine resistance has been found in South Africa and Mozambique [20]. Mefloquine is recommended as a prophylaxis for people traveling to malaria-endemic areas [1]. Monthly incidence data for Swaziland’s four major administrative regions of Hhohho, Manzini, Lubombo, and Shiselweni are available after 2000. Hence, the monthly incidence data in Swaziland from 2001 to 2015 were used to evaluate the influence of climate variations. The geographic clusters of imported and locally acquired cases between 2010 and 2015 are shown in Additional file 2 for reference.

Climate data

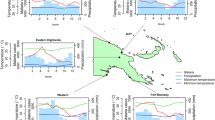

Meteorological data, including maximum and minimum temperature and precipitation, from 1985 to 2015 are available from 14 weather stations within Swaziland. However, not all stations collected complete data throughout the study period, so the climatic data were mainly obtained from one station that has as much data as possible in each of the four major administrative regions (Fig. 1). Monthly climatic variables were summarized from daily maximum temperature, daily minimum temperature, and daily precipitation (inches). To handle missing data, proxy environmental parameters were derived from satellite remote sensing images using EASTWeb software [21]. Daytime and nighttime land surface temperatures (LST) were derived from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) MOD11A2 product, and precipitation was derived from Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) microwave satellite images (3B42 Version 7 product). Although land surface temperature and air temperature are not the same measurements, these variables are strongly correlated [21, 22]. Pearson correlation coefficients, ranging from 0.72 to 0.92, indicated a strong correlation between weather station and remote sensing data (Additional file 3). Finally, linear regression models were constructed to interpolate missing values, and the predicted climatic parameter values were used in the analysis.

Regional climate phenomena were also considered in the analysis. The multivariate El Niño Southern Oscillation Index (MEI), which is an integration of six atmospheric variables, was selected to evaluate the influence of irregular climate variations. Positive values indicate a warm phase (El Niño) and negative values indicate a cold phase (La Niña) [23]. The MEI is available from the Earth System Research Laboratory, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (http://www.esrl.noaa.gov). Malaria and climate data were processed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc. Cary, NC, USA).

Time-series analysis

Monthly malaria incidence and meteorological variables from 2001 to 2015 were analyzed using a seasonal autoregressive integrated moving average (SARIMA) model. In this analysis, time-series data with regular seasonality were decomposed into seasonal and non-seasonal components. Differencing was applied to remove non-stationarity. The simplified notation for SARIMA is

where p indicates the non-seasonal autoregressive (AR) order, d is non-seasonal differencing, and q indicates the non-seasonal moving average (MA) order. P, D, and Q are the corresponding seasonal components. S indicates the period, which in this case is 12 months. The importance of climate variables was assessed by the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), where a smaller AIC indicates better model performance [24].

Non-linear relationships between climate conditions and mosquito ecology have been reported previously [25,26,27]. In areas where malaria risk was found to be associated with monthly climate variations in the time-series model, we used distributed lag non-linear models (DLNM) to investigate non-linear relationships between climate factors and malaria transmission. Multicollinearity in lagged effects and non-linear relationships can be handled by using the bi-dimensional function [28,29,30]. The model is expressed as

under a quasi-Poisson assumption to overcome overdispersion. Y t indicates the monthly number of malaria cases, while log(μ t ) is the expected monthly malaria incidence, and X t,h indicates climatic variables at month t and lag month h. H is the maximum lag (12), Pop is an offset to control for the underlying population, and α, β k , and ε t are the intercept, coefficients of covariates, and error term respectively. To control for seasonality, year and smoothed month with degree of freedom (ρ = 6) were also included. The natural cubic smooth function was applied to maximum temperature, minimum temperature, precipitation, and the multivariate El Niño Southern Oscillation Index. SARIMA and DLNM analysis were carried out in R 3.2.5 using the packages dlnm and forecast.

Results

Monthly malaria incidence in Swaziland between 2001 and 2015 is shown in Fig. 2. Malaria transmission stayed below one per thousand population except for the period between 2005 and 2010. During this period, the increase in incidence was highest in the Lubombo administrative region, followed by the Hhohho, Shiselweni, and Manzini administrative regions.

Multiple climatic variables fitted by SARIMA models in each region are listed in Table 1. The analysis selected the best fitted model including parameters for autoregressive, moving average, and seasonal component of different order. The results indicate that temperature and rainfall were strongly seasonal, and were thus captured by the seasonal components (P, D, Q). However, the seasonality of malaria incidence was captured only in Lubombo and Manzini. The MEI did not show seasonality; it merely echoed its irregular characteristics.

To evaluate the importance of climate conditions in relation to malaria incidence, multivariate SARIMA models were constructed to integrate specific climate variables into malaria SARIMA models in each area (Table 2). For instance, the malaria (2,1,1) model (Table 1) was used in the Hhohho region, and other climatic variables were included in the model to evaluate climatic parameters that can better explain malaria transmission. The effect of climate variables on malaria transmission in different areas was assessed by AIC values, which would decrease if incorporating the climate variables improved the predictive power of the model of malaria transmission. In Lubombo and Hhohho, precipitation was associated with malaria transmission risk (AIC difference: −4.17 in Hhohho and −5.75 in Lubombo) (Table 2). Maximum temperature was also an important parameter in Lubombo (AIC difference: −3.46). In Manzini and Shiselweni, climate parameters did not increase the predictive performance of the malaria models, and thus probably had less of an effect on malaria transmission.

The DLNM approach was used to scrutinize the relationships between climate conditions and malaria transmission in Lubombo and Hhohho (Figs. 3, 4). The results showed that malaria transmission risk increased in Hhohho when the maximum temperature was above 25 °C or the minimum temperature was above 15 °C, with the effect of minimum temperature especially pronounced at a 2-month lag. Monthly precipitation above 10 in. also exhibited continuous effects, which predominated at the 6–10-month lag. In Lubombo, a maximum temperature above 30 °C increased malaria transmission risk predominantly 2 months later, as did higher rainfall (above around 5 in.) in the previous four to 6 months. The effect of the MEI was relatively weak and arbitrary in both areas (Figs. 3, 4).

Discussion

This study is a preliminary analysis of the impact of climate variations on malaria transmission in Swaziland between 2001 and 2015. As the country approaches malaria elimination, efforts now focus on detecting all cases in Swaziland’s remaining receptive areas and preventing onward local transmission [6, 31]. The success of malaria control in Swaziland is attributable mostly to the Lubombo Spatial Development Initiative (LSDI), which began in 1999 and ended in 2011 [6]. The Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland (MOSASWA) cross-border malaria elimination initiative launched in 2015 seeks to renew regional efforts to accelerate malaria elimination [3]. Climate conditions are an important factor in altering disease ecology and transmission probability, not only in Swaziland, but also in neighbouring countries such as Mozambique and South Africa.

This study indicated that climate conditions were more important in the Hhohho and Lubombo administrative regions, implying that residents in these areas are at higher risk of infection when temperatures and precipitation are suitable for malaria transmission. The increased incidence in Lubombo and Hhohho between 2005 and 2010 might be associated with climate variations. Correlations among climatic parameters, mosquito development, and parasite life cycle (specifically extrinsic incubation period) have been noted elsewhere [32,33,34]. Dlamini et al. constructed multiple models that correlate mosquito larva abundance with 4 weeks lagged land surface temperature [35]. The non-linear patterns of temperature and precipitation relevant to malaria transmission have been discussed as well [36, 37].

The impact of regional climate phenomena on malaria transmission was also studied recently. Bouma et al. showed that El Niño conditions might have contributed to the 2016–2017 malaria outbreaks in Ethiopia [16]. Hashizume et al. also observed that the Indian Ocean Dipole (IOD) exhibits a 4-year cycle coherent with malaria seasons in the East African highlands [38]. Severe flooding due to extreme rainfall have also caused malaria outbreaks in the highland areas of western Uganda [39]. Although the multivariate El Niño Southern Oscillation Index (MEI) is not strongly associated with malaria transmission risk in Swaziland, public health authorities should nevertheless be vigilant of future climate changes and extreme local weather events that may affect ongoing malaria elimination strategies. For instance, vector control should continue along with case management, since the Anopheles spp. remains active in Swaziland.

Lubombo and Hhohho are two areas vulnerable to malaria transmission because of climate variations, and the two regions correspond to the cluster of locally acquired cases (Additional file 2). In contrast, most imported cases are clustered mainly near Manzini and are probably due to migration or domestic and cross-border travel. These results indicate that climate conditions might be a major driver of malaria transmission in the Lowveld ecological region in Swaziland. Accordingly, any climate-based malaria early warning system needs to be especially vigilant in the administrative regions of Hhohho and Lubombo. In addition, limited resources for disease/vector control should be deployed appropriately, noting that imported cases may trigger onward transmission within Swaziland, and that imported and locally acquired cases interact based on “malariogenic potential”, as noted by Reiner et al. [7].

Malaria transmission is influenced by multiple risk factors, and the results should be interpreted with caution or validated further, as the study has several limitations. First, malaria incidence data in the four major administrative areas are only available on a monthly basis from 2001 to 2015. Hence, it is impossible to investigate climate-vulnerable areas at a finer spatial or temporal resolution. Second, non-climatic factors were not included. In particular, there was no fine-scale data available on intervention, vector ecology, or migration and human mobility, which are also important factors driving malaria transmission. As a result, only statistical associations were established, but not causal relationships, between climate parameters and malaria. Climate parameters only partially account for malaria transmission risk. Third, it was not possible to differentiate imported and locally acquired malaria cases during the study period (2001–2015) because travel history has only been recorded since 2010. Thus, it is difficult to identify and verify the true origin of infection. This is not a major issue in long-term climatic models because climate variations affect not only Swaziland but also other neighbouring endemic countries. Fortunately, the NMCP has been actively following up both types of cases since 2010 and continues to collaborate with neighbouring countries to minimize the impact of possible misclassification. In addition, to differentiate between local and imported cases, it is worth noting that the accuracy of the rapid diagnostic test (RDT) could be poor in the low endemicity area among symptomatic patients [40]. The training of microscopy skills should be continued to maintain the efficiency of case management.

Malaria transmission dynamics can be affected by multiple factors at environmental, community, and individual levels. To strengthen the malaria early warning system in Swaziland, the current analysis should be extended. First of all, climate changes and variations are not restricted to national borders, so an analysis based exclusively on Swaziland may be inadequate to detect regional phenomena, especially since Swaziland is land-locked. Malaria transmission will not stop at the border with Mozambique or South Africa; thus, cross-border data sharing and analysis is critical. For example, a regional malaria early warning system may prove more useful, and could potentially be implemented through the MOSASWA initiative. Under such a system, an outbreak in Mozambique due to heavy rainfall might indicate an imminent spike in cases imported into Swaziland, even though there may not be unusual weather-related events in the latter.

Second, the climate effect could be buffered by different levels of herd immunity, especially for an area with high transmission intensity [12]. Although the effect might not be significant in Swaziland because of its currently low transmission status, a future regional analysis, which will include different neighbouring countries in southern Africa, should consider the interaction between climate and immunity. For example, in areas where local transmission is more persistent, it will probably be desirable to consider the impact of herd immunity on transmission, and its potential to also regulate transmission by limiting the recruitment of susceptible hosts [12, 41, 42]. Mathematical approaches could be useful in developing a dynamic malaria model to forecast transmission risk under different transmission settings within the MOSASWA area.

Third, non-climate parameters should be integrated in the future analysis, such as land cover/use, vector control, or social networks [43]. Though Swaziland is relatively small, the interaction between climate and landscape-level characteristics could be significant because of its diverse topography. With the continued financial support from and efforts by the NMCP, case management and vector control can be sustained in Swaziland. A mobile population has become the most critical challenge for malaria elimination [3]. Travel history information has been incorporated in the active investigation since 2010 by the NMCP. Social-network or contact-tracing approaches could be considered to evaluate the chains of infection and reveal the origin of infection and onward transmission [5, 44, 45]. It can provide useful information to perform a more accurate targeted control as part of MOSASWA cross-border collaboration.

Conclusions

The impact of climate variations on malaria transmission was evaluated in Swaziland, showing that the Hhohho and Lubombo administrative regions were acutely vulnerable to climatic conditions. While Swaziland is close to a malaria-free status, the development of an early warning system could enhance the efficacy of disease control and provide a sustainable future for malaria elimination.

References

Swaziland Ministry of Health. National malaria elimination strategic plan 2015–2020; 2014.

WHO. Roll back malaria partnership: progress & impact series: focus on Swaziland; 2012.

Moonasar D, Maharaj R, Kunene S, Candrinho B, Saute F, Ntshalintshali N, et al. Towards malaria elimination in the MOSASWA (Mozambique, South Africa and Swaziland) region. Malar J. 2016;15:419.

Sharp BL, Kleinschmidt I, Streat E, Maharaj R, Barnes KI, Durrheim DN, et al. Seven years of regional malaria control collaboration–Mozambique, South Africa, and Swaziland. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:42–7.

Koita K, Novotny J, Kunene S, Zulu Z, Ntshalintshali N, Gandhi M, et al. Targeting imported malaria through social networks: a potential strategy for malaria elimination in Swaziland. Malar J. 2013;12:219.

Maharaj R, Moonasar D, Baltazar C, Kunene S, Morris N. Sustaining control: lessons from the Lubombo spatial development initiative in southern Africa. Malar J. 2016;15:409.

Reiner RC, Le Menach A, Kunene S, Ntshalintshali N, Hsiang MS, Perkins TA, et al. Mapping residual transmission for malaria elimination. Elife. 2015;4:e09520.

Caminade C, Kovats S, Rocklov J, Tompkins AM, Morse AP, Colon-Gonzalez FJ, et al. Impact of climate change on global malaria distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:3286–91.

Chretien J, Anyamba A, Small J, Britch S, Sanchez JL, Halbach AC, et al. Global climate anomalies and potential infectious disease risks: 2014–2015. PLoS Curr. 2015. doi:10.1371/currents.outbreaks.95fbc4a8fb4695e049baabfc2fc8289f.

Edlund S, Davis M, Douglas JV, Kershenbaum A, Waraporn N, Lessler J, et al. A global model of malaria climate sensitivity: comparing malaria response to historic climate data based on simulation and officially reported malaria incidence. Malar J. 2012;11:331.

Onyango EA, Sahin O, Awiti A, Chu C, Mackey B. An integrated risk and vulnerability assessment framework for climate change and malaria transmission in East Africa. Malar J. 2016;15:551.

Laneri K, Paul RE, Tall A, Faye J, Diene-Sarr F, Sokhna C, et al. Dynamical malaria models reveal how immunity buffers effect of climate variability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:8786–91.

Mabaso ML, Kleinschmidt I, Sharp B, Smith T. El Nino Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and annual malaria incidence in Southern Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2007;101:326–30.

Hashizume M, Terao T, Minakawa N. The Indian Ocean Dipole and malaria risk in the highlands of western Kenya. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:1857–62.

Chaves LF, Satake A, Hashizume M, Minakawa N. Indian Ocean dipole and rainfall drive a Moran effect in East Africa malaria transmission. J Infect Dis. 2012;205:1885–91.

Bouma MJ, Siraj AS, Rodo X, Pascual M. El Nino-based malaria epidemic warning for Oromia, Ethiopia, from August 2016 to July 2017. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21:1481–8.

Chaves LF, Hashizume M, Satake A, Minakawa N. Regime shifts and heterogeneous trends in malaria time series from Western Kenya Highlands. Parasitology. 2012;139:14–25.

Cohen JM, Dlamini S, Novotny JM, Kandula D, Kunene S, Tatem AJ. Rapid case-based mapping of seasonal malaria transmission risk for strategic elimination planning in Swaziland. Malar J. 2013;12:61.

Ministry for Health and Social Welfare. Malaria elimination strategy 2008–2015; 2008.

Deacon HE, Freese JA, Sharp BL. Drug-resistant Plasmodium falciparum malaria in the eastern Transvaal. S Afr Med J. 1994;84:394–5.

Chuang TW, Wimberly MC. Remote sensing of climatic anomalies and West Nile virus incidence in the northern Great Plains of the United States. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e46882.

Krehbiel C, Henebry GM. A comparison of multiple datasets for monitoring thermal time in urban areas over the U.S. Upper Midwest. Remote Sens. 2016;8:297.

Wolter K, Timlin MS. El Niño/Southern Oscillation behaviour since 1871 as diagnosed in an extended multivariate ENSO index (MEI.ext). Int J Climatol. 2011;31:1074–187.

Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Model selection and multimodel inference: a practical information theoretic approach. New York: Springer; 2002.

Descloux E, Mangeas M, Menkes CE, Lengaigne M, Leroy A, Tehei T, et al. Climate-based models for understanding and forecasting dengue epidemics. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1470.

Gilioli G, Mariani L. Sensitivity of Anopheles gambiae population dynamics to meteo-hydrological variability: a mechanistic approach. Malar J. 2011;10:294.

Chaves LF, Pascual M. Comparing models for early warning systems of neglected tropical diseases. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2007;1:e33.

Gasparrini A. Distributed lag linear and non-linear models in R: the Package dlnm. J Stat Softw. 2011;43:1–20.

Yang J, Ou CQ, Ding Y, Zhou YX, Chen PY. Daily temperature and mortality: a study of distributed lag non-linear effect and effect modification in Guangzhou. Environ Health. 2012;11:63.

Muggeo VM, Hajat S. Modelling the non-linear multiple-lag effects of ambient temperature on mortality in Santiago and Palermo: a constrained segmented distributed lag approach. Occup Environ Med. 2009;66:584–91.

Sturrock HJ, Roberts KW, Wegbreit J, Ohrt C, Gosling RD. Tackling imported malaria: an elimination endgame. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93:139–44.

Abiodun GJ, Maharaj R, Witbooi P, Okosun KO. Modelling the influence of temperature and rainfall on the population dynamics of Anopheles arabiensis. Malar J. 2016;15:364.

Midekisa A, Beyene B, Mihretie A, Bayabil E, Wimberly MC. Seasonal associations of climatic drivers and malaria in the highlands of Ethiopia. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:339.

Teklehaimanot HD, Lipsitch M, Teklehaimanot A, Schwartz J. Weather-based prediction of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in epidemic-prone regions of Ethiopia I. Patterns of lagged weather effects reflect biological mechanisms. Malar J. 2004;3:41.

Dlamini SN, Franke J, Vounatsou P. Assessing the relationship between environmental factors and malaria vector breeding sites in Swaziland using multi-scale remotely sensed data. Geospat Health. 2015;10:302.

Colon-Gonzalez FJ, Tompkins AM, Biondi R, Bizimana JP, Namanya DB. Assessing the effects of air temperature and rainfall on malaria incidence: an epidemiological study across Rwanda and Uganda. Geospat Health. 2016;11:379.

Shimaponda-Mataa NM, Tembo-Mwase E, Gebreslasie M, Achia TN, Mukaratirwa S. Modelling the influence of temperature and rainfall on malaria incidence in four endemic provinces of Zambia using semiparametric Poisson regression. Acta Trop. 2016;166:81–91.

Hashizume M, Chaves LF, Minakawa N. Indian Ocean Dipole drives malaria resurgence in East African highlands. Sci Rep. 2012;2:269.

Boyce R, Reyes R, Matte M, Ntaro M, Mulogo E, Metlay JP, et al. Severe flooding and malaria transmission in the western Ugandan Highlands: implications for disease control in an era of global climate change. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1403–10.

Ranadive N, Kunene S, Darteh S, Ntshalintshali N, Nhlabathi N, Dlamini N, et al. Limitations of rapid diagnostic testing in patients with suspected malaria: a diagnostic accuracy evaluation from Swaziland, a low-endemicity country aiming for malaria elimination. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:1221–7.

Chaves LF, Kaneko A, Pascual M. Random, top-down, or bottom-up coexistence of parasites: malaria population dynamics in multi-parasitic settings. Ecology. 2009;90:2414–25.

Pascual M, Cazelles B, Bouma MJ, Chaves LF, Koelle K. Shifting patterns: malaria dynamics and rainfall variability in an African highland. Proc Biol Sci. 2008;275:123–32.

Chaves LF, Koenraadt CJ. Climate change and highland malaria: fresh air for a hot debate. Q Rev Biol. 2010;85:27–55.

Vazquez-Prokopec GM, Montgomery BL, Horne P, Clennon JA, Ritchie SA. Combining contact tracing with targeted indoor residual spraying significantly reduces dengue transmission. Sci Adv. 2017;3:e1602024.

Eames KT, Keeling MJ. Contact tracing and disease control. Proc Biol Sci. 2003;270:2565–71.

Authors’ contributions

TWC conducted the study framework and drafted the manuscript. AS, NN, NM, ES, SM, DP, and SK helped to collect data and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the support of the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP), the Swaziland Ministry of Health, the Swaziland Meteorological Service, and the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHAI). We would also like to thank Dr. Luis Fernando Chaves for his valuable input.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data used in this study are available from the National Malaria Control Programme (NMCP), the Ministry of Health in Swaziland.

Funding

The project is funded by Global Fund to fight AIDS, TB, and Malaria.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

12936_2017_1874_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2. Spatial distributions of imported and locally acquired malaria cases in Swaziland, 2010-2015. The base map was produced by kernel density estimation. (The imported cases mainly clustered in Manzini. The locally acquired cases mainly clustered in Hhohho and Lubombo).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Chuang, TW., Soble, A., Ntshalintshali, N. et al. Assessment of climate-driven variations in malaria incidence in Swaziland: toward malaria elimination. Malar J 16, 232 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1874-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-017-1874-0