Abstract

Background

Prenatal exposure to Plasmodium falciparum affects development of protective immunity and susceptibility to subsequent natural challenges with similar parasite antigens. However, the nature of these effects has not been fully elucidated. The aim of this study was to determine the effect of prenatal exposure to P. falciparum on susceptibility to natural malaria infection, with a focus on median time from birth to first clinical malaria episode and frequency of clinical malaria episodes in the first 2 years of life.

Methods

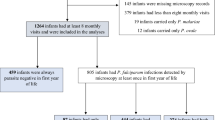

A prospective birth cohort study was conducted in Rufiji district in Tanzania, between January 2013 and December 2015. Infants born to mothers with P. falciparum in the placenta at time of delivery were defined as exposed, and infants born to mothers without P. falciparum parasites in placenta were defined as unexposed. Placental infection was established by histological techniques. Out of 206 infants recruited, 41 were in utero exposed to P. falciparum and 165 infants were unexposed. All infants were monitored for onset of clinical malaria episodes in the first 2 years of life. The outcome measure was time from birth to first clinical malaria episode, defined by fever (≥37 °C) and microscopically determined parasitaemia. Median time to first clinical malaria episode between exposed and unexposed infants was assessed using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and comparison was done by log rank. Association of clinical malaria episodes with prenatal exposure to P. falciparum was assessed by multivariate binary logistic regression. Comparative analysis of mean number of clinical malaria episodes between exposed and unexposed infants was done using independent sample t test.

Results

The effect of prenatal exposure to P. falciparum infection on clinical malaria episodes was statistically significant (Odds Ratio of 4.79, 95 % CI 2.21–10.38, p < 0.01) when compared to other confounding factors. Median time from birth to first clinical malaria episode for exposed and unexposed infants was 32 weeks (95 % CI 30.88–33.12) and 37 weeks (95 % CI 35.25–38.75), respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.003). The mean number of clinical malaria episodes in exposed and unexposed infants was 0.51 and 0.30 episodes/infant, respectively, and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.038).

Conclusions

Prenatal exposure to P. falciparum shortens time from birth to first clinical malaria episode and increases frequency of clinical malaria episodes in the first 2 years of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Sub-Saharan Africa still faces high rates of infant mortality due to Plasmodium falciparum infections, despite strategies put in place for the control of malaria [1]. In Tanzania, where this study was conducted, more than 80 % of the malaria infections are linked to P. falciparum [2]. It has been demonstrated that malaria due to P. falciparum during pregnancy may affect newborn susceptibility to subsequent malaria infections, and that infants born to mothers with placental malaria are exposed in utero to P. falciparum antigens [3–7]. The effect of early exposure to P. falciparum antigen on development of infant protective immunity has been studied and in utero exposed infants have been reported to have limited protective immune response to subsequent natural challenges with the same parasite antigen [8–10]. Epidemiological studies in some endemic areas have consistently demonstrated differences between children born to mothers with placental malaria (pm+) and those born to mothers without placental malaria (pm−).

A study conducted in Cameroon demonstrated that the prevalence of malaria parasitaemia in infants aged four to 6 months was higher in those born to pm+ mothers compared to the controls [11], while a study in Malawi demonstrated that the risk of mortality due to malaria was higher in infants born to pm+ mothers compared to those born to pm− mothers [12]. Although it has been established that prenatal exposure to malaria parasites influences the subsequent susceptibility of infants to malaria infection, there are other factors that may influence susceptibility to early malaria infections. The identified factors include but not limited to age of the mother, use of intermittent preventive treatment during pregnancy, gravidity and season of birth may influence the degree of exposure to malaria infection [13]. The dearth of information on the compounded effect of other factors and prenatal sensitization to the parasite antigens and their effects on subsequent susceptibility to the natural challenge of P. falciparum infection indicate that there remains a need to characterize this phenomenon.

This study was designed to systematically and prospectively follow up a birth cohort of infants for a period of 2 years, to delineate the effects of prenatal exposure to P. falciparum antigens and other factors (gravidity, season of birth, age of the mother, and infant birth weight) that could influence susceptibility, with respect to frequency and time from birth to first clinical malaria episode in infants born to pm+ and pm− mothers.

Methods

Study area

Four public health facilities (Utete, Mohoro Ikwiriri and Kibiti) located in Rufiji District, Coast Region in Tanzania were involved in this study. The area is low-lying, below 500 m above sea level and most of its surface area lies within the fertile flood plain of Rufiji River. Rufiji district typically experiences a long rainy season between February and May and a shorter, less intense one from October to December. Annual rainfall ranges between 800 and 1000 mm in the Rufiji River basin and malaria transmission occurs all year round.

Study design, study population and recruitment of research participants

This was a prospective birth cohort study which included 206 mother infant pairs with infants aged 0–24 months. The criteria for recruitment of mothers included HIV seronegativity (pregnant mothers are routinely screened for HIV during prenatal visits in the study area) and confirmation to stay within the study area for a period of 2 years to facilitate follow up of infants to the age of 2 years. In order to maintain confidentiality, all study participants were assigned code numbers. The group assignment of the study participants was based on placental malaria status established by examination of placental tissues using histological techniques. Histological classification was not done in this study but the presence or absence of P. falciparum in the placenta at the time of delivery confirmed by histopathology was used to categorize the mothers and their infants. Mothers who had P. falciparum in their placenta at time of delivery confirmed by histopathology were defined as placental malaria positive (pm+) and their infants were defined as exposed to P. falciparum, while mothers who had no P. falciparum infection at time of delivery were defined as placental malaria negative (pm−) and their infants were defined as unexposed.

Placental tissue collection, storage and histopathological examination

In order to establish placental malaria infection histological samples were collected and processed. Briefly, following delivery, the maternal side of placenta was placed in an upright position and cleaned with sterile normal saline and a health paracentric area was then incised. Maternal placental tissue was examined using histopathologic techniques as previously described [14]. A full thickness of placental biopsy (8 cm3) was collected, by a trained and experienced nurse, from the maternal surface halfway between the placental edge and the insertion of the umbilical cord, within 4 hours of placental expulsion. The placental tissue was fixed in 10 % neutral-buffered formalin. Following fixation, placental tissue was trimmed and placed into histopathological cassettes, processed on an automated tissue processor overnight, embedded in paraffin wax, and then sectioned on a microtome to obtain 5-nm slices. The slices were placed in warm water bath at about 56 °C and transferred onto a microscope slide and left to dry and adhere to the slide. The placental sections were stained using haematoxylin and eosin and were then examined using light microscopic technique. Results were reported as placental malaria positive (Fig. 1) or placental malaria negative.

Demonstration of Plasmodium falciparum in intervillous erythrocytes in histological section of placenta stained using haematoxylin and eosin. 100× magnification. The section demonstrates P. falciparum in intervillous erythrocytes. An arrow is pointing at one of the parasitized (P.falciparum) intervillous red blood cell

Examination of placental blood specimen using a light microscope

Using fresh placental blood specimen, thin smears were prepared, dried and fixed in methyl alcohol. Thick smears were not subjected to any fixative but dried and stained with 10 % working Giemsa for 10 min, washed, dried, and kept in slide boxes for microscopic examination. All smears were read independently by two trained laboratory technologists and discordant results on malaria species and parasite count were resolved by the Investigator. Results were reported as positive or negative for P. falciparum (Fig. 2). Documentation by photograph was done using Leica microsystem for future reference.

Follow up of recruited infants and determination of clinical malaria episodes

Recruited infants were followed-up both at community and facility levels by trained research assistants. Scheduled visits were conducted regularly at 3 months intervals for a period of 2 years from birth while unscheduled visits were conducted whenever recruited infants had signs/symptoms of illness. Clinical examination was conducted by a trained study physician and clinical signs/symptoms were recorded on designated follow up questionnaire forms. Blood smears were collected for determination of clinical malaria infection using light microcopy technique. Clinical malaria was defined as fever (≥37.5 °C) with microscopically determined parasitaemia. Following the initial malaria episode, a new clinical malaria infection was defined as presence of asexual P. falciparum parasites in blood with fever (≥37.5 °C) after a period of 2 weeks or beyond from the previously treated clinical malaria episode. All Infants who were diagnosed of clinical malaria infection were treated within the routine system at the health facilities. In addition, infants who were diagnosed of non-malaria diseases were attended and provided with standard medical care during the entire study period.

Time to first clinical malaria episode was determined in all recruited infants in order to assess the vulnerability to malaria infection. Specific birth dates for the recruited infants and dates when they experienced clinical malaria episode for the first time were systematically recorded. Time elapsed from birth to diagnosis of clinical malaria episode was defined as the time to first clinical malaria episode. This was recorded for each recruited infant in weeks and the median time for each group was determined. Subsequent malaria episodes experienced by recruited infants were also recorded on the designed forms to determine the frequency of clinical malaria episodes during the first 24 months of life.

Data management and analysis

Double-entry system was employed in data entry process. The data were cleaned and analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), IBM version 20.0. Frequencies and cross-tabulations were used to summarize baseline socio-demographic characteristics between mothers with and without placental malaria (pm+ and pm−, respectively) and the association of prenatal exposure to P. falciparum with socio-demographic characteristics was determined using Chi square test. Comparison of mean number of clinical malaria episodes between exposed and unexposed infants was done using independent sample t test. The median times from birth to first clinical malaria episodes for infants born to mothers with placental malaria (exposed) and infants born to mothers without placental malaria (unexposed) were determined using Kaplan–Meier survival analysis and the comparison was carried out using Log rank test. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to assess the effect of prenatal exposure to P. falciparum on first clinical malaria episode. During the analysis, potential confounders were considered into the multivariate model and these included gravidity, birth weight, age of mother, and infant season of birth. Results were reported as odds ratio where applicable with 95 % confidence intervals. A ‘p’ value of <0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study population

A total of 206 mother-infant pairs were included in the study. Of these, 41 infants were born to pm+ mothers (infants exposed in utero to P. falciparum) and 165 infants were born to pm− mothers (infants not exposed to P. falciparum). Table 1 summarizes the socio-demographic characteristics of the study population. Of 206 mothers recruited 66.9 % (n = 76) were primigravida and 63.1 % (n = 130) were multigravida. Out of 41 mothers who had placental malaria, 58.5 % (n = 24) were primigravida while 41.5 % (n = 17) were multigravida, and the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.01). There was no statistical significant difference between pm+ and pm− mothers on season of birth, level of education and age of mother. The use of insecticide treated bed nets (ITNs) between exposed infants and unexposed was similar (Table 1). The number of infants born with low birth weight was significantly higher in infants born to pm+ mothers compared to those born to pm− mothers, (Table 2) and the difference was statistically significant, p = 0.01.

Time to first clinical malaria episode and the mean number of clinical malaria episodes

The median time from birth to first clinical malaria episode in exposed infants was 32 weeks (95 % CI 30.88–33.12), while in unexposed infants it was 37 weeks (95 % CI 35.25–38.75) and the difference in the median time was statistically significant (p = 0.003, Fig. 3). The mean number of clinical malaria episodes during the first 2 years of life, among infants born to pm+ mothers was 0.51 episodes/infant compared to those born to pm− mothers with 0.30 episodes/infant and the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.038).

The effect of prenatal exposure to Plasmodium falciparum on clinical malaria episodes during the first 2 years of life

The effect of prenatal exposure to P. falciparum on clinical malaria episode was assessed using binary logistic regression. Important confounding factors included gravidity, season of birth, birth weight of infant, and age of mother. The statistical model has shown that fetal in utero exposure to P. falciparum is significantly associated with the vulnerability of infants to clinical malaria episodes (Odds Ratio 4.79, 95 % CI 2.21–10.38 p < 0.05) while other factors did not statistically influence the clinical malaria episodes in a multivariate analysis (Table 3).

Discussion

This prospective birth cohort study sought to delineate the effect of in utero exposure to P. falciparum infection on identified indicators of susceptibility, including time from birth to first clinical malaria episode and mean number of clinical malaria episodes. In addition, the effects of other factors that could confound the effect of in utero exposure to P. falciparum were also assessed. The median time from birth to first clinical malaria episode was significantly shorter in infants exposed in utero to P. falciparum infection than in unexposed infants. Clinical malaria infections in both exposed and unexposed infants were experienced beyond 6 months of age. This finding was corroborated by previous studies, which reported that malaria maternal antibodies are protective in the first 6 months of infant life [15–17]. The findings in this study of the occurrence of first clinical malaria episodes after 6 months of age in exposed and unexposed infants may indicate the possible protection of maternal antibodies as already demonstrated [18]. However, the current findings of the time from birth to first clinical malaria episode to be beyond 6 months following the waning of maternal antibodies are not consistent with the findings of a study done in Cameroon which indicated that maternal antibodies were not protective but markers of malaria infection [19].

Previous studies demonstrated that prenatal exposure to P. falciparum influenced the susceptibility to malaria infections by affecting the development of protective immunity against malaria infection through development of immuno-tolerance to the parasite antigen in subsequent malaria infections, rendering the exposed infants to be more susceptible to malaria infection than the unexposed infants [20]. The current study has demonstrated that infants born to placental malaria-positive mothers were more vulnerable and experienced the first clinical malaria episode much earlier in life after birth than infants born to mothers without placental malaria during the first 2 years of life. The other factors that could have influenced exposure to malaria infection, including level of education of the mother and use of ITNs, were similar in all recruited mothers and were therefore not considered as confounding. However, the factors which were considered in multivariate analysis have shown that, the age of the mother, season of birth, weight of infant at birth, and gravidity did not affect clinical malaria episodes in the study area. However, a similar study conducted in Ghana indicated that heterogeneity in exposure is likely to be the dominant factor influencing incidence of malaria in infancy [21]. The findings of the study in Ghana are corroborated by studies which have shown that the level of exposure to infective Anopheles mosquitoes, the environmental factors (which may influence mosquito density) and behavioral factors are important in malaria transmission and have a direct influence on exposure and susceptibility [22, 23].

Although the current study considered some of the factors which could confound the effect of prenatal exposure on susceptibility, it did not incorporate those factors that may have a direct influence on exposure to the parasite.

Lack of influence of the other exposure-related factors in this study is supported by the fact that, in the study area there was an ongoing anti-malaria campaign which involved distribution of ITNs at subsidized cost and emphasis was made on use of IPTp-SP for prevention of malaria during pregnancy as part of National Malaria Control Programme. The impact of this campaign in the study area was reflected in the general malaria prevalence which was reported to be 4.8 % [24]. However, the number of mothers with placental malaria seemed to remain high (n = 41) in the perceived context of the effects of placental malaria to the exposed infants.

In the present study, the mean number of clinical malaria episodes in the first 2 years of life was significantly higher in infants exposed to placental malaria than unexposed. These findings are corroborated by earlier studies, which demonstrated that infants born to pm+ mothers were more susceptible to P. falciparum infection [25–27].

However, a study done in Ghana indicated that the incidence of malaria in infants born to primigravida without placental malaria was significantly lower than that of infants born to primigravida with placental malaria but, there was no significant difference in the incidence of malaria among infants born to multigravida with or without placental malaria [21]. While the findings in infants born to primigravida with or without placental malaria are consistent with the findings in this study, it is notable that the findings in multigravida are not consistent with the finding in primigravida, putting into question the influence of prenatal exposure to the parasite antigen on susceptibility to malaria infection.

In this study, it was noted that a significantly higher proportion of primigravida were placental malaria-positive compared to multigravida (58.5 vs 31.5 %, respectively); hence, the majority of the infants exposed in utero to P. falciparum were born to primigravida compared to multigravida (24 mothers vs 17 mothers, respectively). The increased vulnerability of primigravida to placental malaria compared to other gravidities is corroborated by a study conducted in Angola [28], which demonstrated that primigravida were more susceptible to placental malaria due to demonstrated low levels of antibodies against chondroitin sulfate A; while these antibodies were higher in multigravida [29], which reflected a level of protection against placental malaria [30, 31]. It is possible that the demonstrated high levels of antibodies against chondroitin sulfate A in multigravida may have a synergistic effect on the protection conferred by maternal antibodies to infants born of multigravida. This conjecture is based on findings by a study which demonstrated that antibody responses to the N-terminal region of VAR 2CSA (P. falciparum antigen) during early pregnancy were associated with reduced risks for infection and low birth weight [31].

Although a direct influence of gravidity on susceptibility was not demonstrated in this study, one study conducted in the northern part of Tanzania showed that gravidity interacted with prenatal exposure to malaria and played a role in affecting susceptibility of infants to malaria infections [32]. This study, demonstrated that prenatal exposure to malaria significantly affected the susceptibility of infants to first clinical malaria episodes in a multivariate analysis, while gravidity did not significantly associate with time to first clinical malaria episode. It is hypothesized that this discrepancy may not be inherent to a basic biological or immunological factor because being primigravida is a risk to acquiring placental malaria, which, in essence, may predispose the infant to immune-tolerance and, hence, increasing susceptibility to subsequent malaria infection.

Conclusion

Prenatal exposure to P. falciparum significantly influences vulnerability to malaria infection. Infants exposed in utero to parasite antigens succumb early to clinical malaria episodes and experience more frequent clinical malaria episodes than unexposed infants during the first 2 years of life.

Abbreviations

- AOR:

-

adjusted odds ratio

- IPTp:

-

intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy

- ITN:

-

insecticide-treated bed net

- SP:

-

sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine

- Pm+:

-

placental malaria positive

- Pm−:

-

placental malaria negative

References

Lawal B, Shittu OK, Kabiru AY, Jigam AA, Umar MB, Berinyuy EB, et al. Potential antimalarials from African natural products: a review. J Intercult Ethnopharmacol. 2015;4:318–43.

World malaria situation. Division of Control of Tropical Diseases. World Health Organization, Geneva. World Health Stat Q. 1990;1992(45):257–66.

Fievet N, Varani S, Ibitokou S, Briand V, Louis S, Perrin RX, et al. Plasmodium falciparum exposure in utero, maternal age and parity influence the innate activation of foetal antigen presenting cells. Malar J. 2009;8:251.

Ismaili J, van der Sande M, Holland MJ, Sambou I, Keita S, Allsopp C, et al. Plasmodium falciparum infection of the placenta affects newborn immune responses. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;133:414–21.

King CL, Malhotra I, Wamachi A, Kioko J, Mungai P, Wahab SA, et al. Acquired immune responses to Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 in the human fetus. J Immunol. 2002;168:356–64.

Dent A, Malhotra I, Mungai P, Muchiri E, Crabb BS, Kazura JW, et al. Prenatal malaria immune experience affects acquisition of Plasmodium falciparum merozoite surface protein-1 invasion inhibitory antibodies during infancy. J Immunol. 2006;177:7139–45.

Broen K, Brustoski K, Engelmann I, Luty AJ. Placental Plasmodium falciparum infection: causes and consequences of in utero sensitization to parasite antigens. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;151:1–8.

Desowitz RS, Elm J, Alpers MP. Prenatal immune hypersensitization to malaria: Plasmodium falciparum-specific IgE antibody in paired maternal and cord sera from Papua New Guinea. PNG Med J. 1992;35:303–5.

Mackroth MS, Malhotra I, Mungai P, Koech D, Muchiri E, King CL. Human cord blood CD4+ CD25hi regulatory T cells suppress prenatally acquired T cell responses to Plasmodium falciparum antigens. J Immunol. 2011;186:2780–91.

Bardaji A, Sigauque B, Sanz S, Maixenchs M, Ordi J, Aponte JJ, et al. Impact of malaria at the end of pregnancy on infant mortality and morbidity. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:691–9.

Le Hesran JY, Cot M, Personne P, Fievet N, Dubois B, Beyeme M, et al. Maternal placental infection with Plasmodium falciparum and malaria morbidity during the first 2 years of life. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146:826–31.

McDermott JM, Wirima JJ, Steketee RW, Breman JG, Heymann DL. The effect of placental malaria infection on perinatal mortality in rural Malawi. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;55(1 Suppl):61–5.

Apinjoh TO, Anchang-Kimbi JK, Mugri RN, Njua-Yafi C, Tata RB, Chi HF, et al. Determinants of infant susceptibility to malaria during the first year of life in South Western cameroon. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2015;2:ofv012.

Parekh FK, Davison BB, Gamboa D, Hernandez J, Branch OH. Placental histopathologic changes associated with subclinical malaria infection and its impact on the fetal environment. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2010;83:973–80.

Wilson PT, Malhotra I, Mungai P, King CL, Dent AE. Transplacentally transferred functional antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum decrease with age. Acta Trop. 2013;128:149–53.

McGuinness D, Koram K, Bennett S, Wagner G, Nkrumah F, et al. Clinical case definitions for malaria: clinical malaria associated with very low parasite densities in African infants. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:527–31.

Stanisic DI, Fowkes FJ, Koinari M, Javati S, Lin E, Kiniboro B, et al. Acquisition of antibodies against Plasmodium falciparum merozoites and malaria immunity in young children and the influence of age, force of infection, and magnitude of response. Infect Immun. 2014;83:646–60.

Dobbs KR, Dent AE. Plasmodium malaria and antimalarial antibodies in the first year of life. Parasitology. 2016;143:129–38.

Riley EM, Wagner GE, Ofori MF, Wheeler JG, Akanmori BD, Tetteh K, et al. Lack of association between maternal antibody and protection of African infants from malaria infection. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5856–63.

Malhotra I, Dent A, Mungai P, Wamachi A, Ouma JH, Narum DL, et al. Can prenatal malaria exposure produce an immune tolerant phenotype? A prospective birth cohort study in Kenya. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000116.

Asante KP, Owusu-Agyei S, Cairns M, Dodoo D, Boamah EA, Gyasi R, et al. Placental malaria and the risk of malaria in infants in a high malaria transmission area in Ghana: a prospective cohort study. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:1504–13.

Le Port A, Cottrell G, Chandre F, Cot M, Massougbodji A, Garcia A. Importance of adequate local spatiotemporal transmission measures in malaria cohort studies: application to the relation between placental malaria and first malaria infection in infants. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178:136–43.

Cottrell G, Kouwaye B, Pierrat C, le Port A, Bouraima A, Fonton N, et al. Modeling the influence of local environmental factors on malaria transmission in Benin and its implications for cohort study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e28812.

Farnert A, Yman V, Homann MV, Wandell G, Mhoja L, Johansson M, et al. Epidemiology of malaria in a village in the Rufiji River Delta, Tanzania: declining transmission over 25 years revealed by different parasitological metrics. Malar J. 2014;13:459.

De Beaudrap P, Turyakira E, Nabasumba C, Tumwebaze B, Piola P, Boum Ii Y, et al. Timing of malaria in pregnancy and impact on infant growth and morbidity: a cohort study in Uganda. Malar J. 2016;15:92.

Kassam SN, Nesbitt S, Hunt LP, Oster N, Soothill P, Sergi C. Pregnancy outcomes in women with or without placental malaria infection. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;93:225–32.

Schwarz NG, Adegnika AA, Breitling LP, Gabor J, Agnandji ST, Newman RD, et al. Placental malaria increases malaria risk in the first 30 months of life. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:1017–25.

Valente B, Campos PA, do Rosario VE, Varandas L, Silveira H. Prevalence and risk factors of Plasmodium falciparum infections in pregnant women of Luanda, Angola. Trop Med Int Health. 2011;16:1206–14.

Dahlback M, Jorgensen LM, Nielsen MA, Clausen TM, Ditlev SB, Resende M, et al. The chondroitin sulfate A-binding site of the VAR2CSA protein involves multiple N-terminal domains. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:15908–17.

Duffy PE. Plasmodium in the placenta: parasites, parity, protection, prevention and possibly preeclampsia. Parasitology. 2007;134(Pt 13):1877–81.

Ndam NT, Denoeud-Ndam L, Doritchamou J, Viwami F, Salanti A, Nielsen MA, et al. Protective antibodies against placental malaria and poor outcomes during pregnancy. Benin. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:813–23.

Mutabingwa TK, Bolla MC, Li JL, Domingo GJ, Li X, Fried M, et al. Maternal malaria and gravidity interact to modify infant susceptibility to malaria. PLoS Med. 2005;2:e407.

Authors’ contributions

DBG, SM, SA, and DT conceived the study, participated in the study protocol development, coordination, and manuscript writing. RM participated in the data analysis and manuscript writing. SG participated in the data generation, coordination and manuscript writing. BS participated in study protocol development, data collection, data management, data analysis, and in the preparation and writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Swedish International Development Cooperation (Sida) for funding this project in all stages. We acknowledge the participation of mothers and infants in the study area and much appreciate the assistance of nurses, laboratory technicians and medical doctors at the health facilities of Utete, Kibiti, Ikwiriri, and Mohoro. The study was funded by The Swedish International Development and Cooperation Agency (Sida).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Data supporting the conclusion are included in the main text.

Consent for publication

All recruited mothers consented for publication of their data and also assented for their infants.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Ethical clearance to conduct the study was granted by the Senate Research and Publications Committee of Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences in Tanzania. Permission to conduct the study in Rufiji District health facilities was granted by the Rufiji District Medical Officer. Written informed consent was obtained from mothers after explanation of the aims and nature of study prior to recruitment and participation in the study. All infants found to have clinical malaria were managed in accordance with the existing national treatment guidelines.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sylvester, B., Gasarasi, D.B., Aboud, S. et al. Prenatal exposure to Plasmodium falciparum increases frequency and shortens time from birth to first clinical malaria episodes during the first two years of life: prospective birth cohort study. Malar J 15, 379 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1417-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12936-016-1417-0