Abstract

Background

Terrein, a major secondary metabolite from Aspergillus terreus, shows great potentials in biomedical and agricultural applications. However, the low fermentation yield of terrein in wild A. terreus strains limits its industrial applications.

Results

Here, we constructed a cell factory based on the marine-derived A. terreus RA2905, allowing for overproducing terrein by using starch as the sole carbon source. Firstly, the pathway-specific transcription factor TerR was over-expressed under the control of a constitutive gpdA promoter of A. nidulans, resulting in 5 to 16 folds up-regulation in terR transcripts compared to WT. As expected, the titer of terrein was improved in the two tested terR OE mutants when compared to WT. Secondly, the global regulator gene stuA, which was demonstrated to suppress the terrein synthesis in our analysis, was deleted, leading to greatly enhanced production of terrein. In addition, LS-MS/MS analysis showed that deletion of StuA cause decreased synthesis of the major byproduct butyrolactones. To achieve an optimal strain, we further refactored the genetic circuit by combining deletion of stuA and overexpression of terR, a higher terrein yield was achieved with a lower background of byproducts in double mutants. In addition, it was also found that loss of StuA (both ΔstuA and ΔstuA::OEterR) resulted in aconidial morphologies, but a slightly faster growth rate than that of WT.

Conclusion

Our results demonstrated that refactoring both global and pathway-specific transcription factors (StuA and TerR) provides a high-efficient strategy to enhance terrein production, which could be adopted for large-scale production of terrein or other secondary metabolites in marine-derived filamentous fungi.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

( +)-Terrein, the major secondary metabolite produced by Aspergillus terreus, was firstly discovered in 1935 and its chemical structure was elucidated in the 1950s. Until recently, terrein has been reported to possess strong anti-tumor activities by targeting multiple pathways, including inhibition of melanin biosynthesis [1,2,3], anti-proliferation [4, 5], suppressing angiogenin production and inducing apoptosis of carcinoma cells [6]. And, terrein displays strong cytotoxicity against ABCG2-expressing breast cancer cells [7], further expanding its potentials in the development of effective therapeutic drugs of cancer. Also, terrein has anti-inflammatory properties in multiple cell lines [8,9,10], phytotoxicity [11], and antimicrobial activities [12]. Interestingly, terrein is the first reported dual inhibitor of QS and c-di-GMP signaling in the pathogenic bacteria Pseudomonas aeruginosa [13], showing potential in the development of novel antibiotics against multidrug-resistant (MDR) gram-negative bacteria. Therefore, terrein has important potential applications in medicine and agriculture.

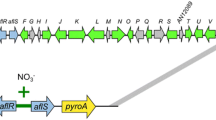

The biosynthetic gene cluster for terrein has been identified, and its biosynthetic pathway has partially elucidated by genetic and biochemical analysis [11]. The cluster, which responsible for terrein synthesis, consists of 11 functional genes. Initially, two acetyl-CoA and four malonyl-CoA units are condensed and catalyzed by TerA, the non-reducing polyketide synthase, to generated 6-hydroxy-2,3-dehydromellein (2,3-dehydro-6-HM). Then, 2,3-dehydro-6-HM is reduced to 6-HM by the multi-domain protein TerB (Fig. 1A). Until now, the biosynthesis pathway from 6-HM to the end product of terrein remains unresolved. Markus Gressler et al. reported that nitrogen or iron starvation acts as the signal to induce terrein production, which depend on function of the global transcription factors AreA, AtfA and HapX [14]. Notably, elevated methionine level promotes terrein production even under non-inducing condition [14].

Like other fungal secondary metabolites, the production level is the bottleneck of further development and application of terrein. Screening of strains and media, and process optimization had been applied to improve terrein titers [15,16,17,18]. However, rational strain engineering has yet been used to improve terrein production until now. In this study, we achieved the high-producing and robust cell factory for terrein synthesis by modifying both the pathway-specific regulator TerR and the global regulator StuA (Fig. 1B). The modified mutants grow faster and produce terrein at gram level by using low-cost substance. We also found that the mutant strain can further reduce the costs by inhibition of biosynthesis of byproducts.

Results

Identification the biosynthetic gene cluster for terrein in marine-derived fungus A. terreus RA2905

( +)-Terrein is the major secondary metabolite produced by A. terreus, highlighted by its broad and excellent biological activities, including antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antitumor activities. Thus, its biosynthesis and regulatory mechanisms has always been a focus of attention in fungal secondary metabolism. A gene cluster of approximately 33 Kb, consisting of 11 functional genes, had been previously identified for terrein biosynthesis in A. terreus SBUG84411. By sequence alignment, we identified the terrein cluster in A. terreus RA2905 (Table 1). Overall, the terrein gene cluster was highly conserved between A. terreus RA2905 and A. terreus SBUG844. The exception is that a protein of 118 amino acids with unknown function specially exists in the terrein cluster of A. terreus RA2905, but not in A. terreus SBUG844. According to previous findings, the protein is not likely involved in biosynthesis of terrein. In the biosynthesis of terrein (Fig. 1A), TerA firstly assembles two acetyl-CoA and four malonyl-CoA to generate 6-hydroxy-2,3-dehydromellein (2). Then, the compound 2 is reduced to 6-hydroxymellein (3) by TerB. Other four unidentified enzymes (TerC, TerD, TerE and TerF) involve in the later biosynthesis pathway from 3 to the end product terrein (1). A Zn2Cys6-class transcription factor, named TerR, was presented in RA2905. It had been previously reported that TerR played a positive role in the regulation of expression of other terrein biosynthesis genes in SBUG844 [14].

To determine whether A. terreus RA2905 has the ability to synthesize terrein, compounds in the crude extracts from its rice cultures were chemically purified and structurally characterized. One of these compounds (30 mg) with an appearance of white power was obtained, and its molecular formula was determined as C8H10O3 by the HR–ESI–MS data at 309.2 [2 M + H]+, which was consistent with the formula of terrein reported previously. Moreover, our 1H and 13C NMR data further confirmed the obtained compound was terrein (Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Figure S2). Together, these results suggested that A. terreus RA2905 could synthesize terrein, but the production titer was low.

Overexpression of pathway-specific transcription factor TerR to improve terrein yield

To activate the terrein cluster expression, firstly, we over-expressed the terR gene in RA2905. The constitutive and strong promoter from glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of A. nidulans was PCR-amplified and used to drive terR overexpression. Then, the terR expression cassette was fused with the selection marker gene pyrg, and then transformed into uracil autography mutant ΔpyrG established previously [19]. A total of 11 transformants with uracil prototroph were obtained, and five of them have the whole expression cassette by diagnostic PCR analysis. After further verification by using quantative PCR, OEterR-1 and OEterR-6 showing increased expression level in comparison to that of WT, were used for further analysis. The fungal phenotype and conidial development of two terR overexpression mutants and WT were analyzed (Fig. 2). The results showed that overexpression of terR has a faint effect on fungal growth and asexual development in A. terreus RA2905 (Fig. 2). The OEterR-6 mutant showed slightly faster growth rate than that of WT on solid plates (Fig. 2). Both terR overexpression mutants produced largely equal amount of conidia on all plates tested (Fig. 2).

By expected, the production of terrein was significantly improved in terR overexpression mutants compared to WT (Fig. 3A). Based on our preliminary data, a low-cost medium TFM, consisting of starch and peptone as carbon and nitrogen resource, was used for fermentation production of terrein. The 7-day fermentation, terrein were organically extracted and the titer was determined by HPLC. Our result showed that the titer of terrein was 0.5- and twofold improved in OEterR-1 and OEterR-6, respectively, as compared with that in WT strain (Fig. 3A). These results further demonstrated that TerR was a specific regulator of terrein, and its overexpression represented an efficient strategy to enhance terrein biosynthesis.

Yields of terrein and biomass in all mutant and WT strains. Fungal mycelia (10 g/L) were cultured in TFM media at 28 °C, 150 rpm for 7d, and yields of terrein and biomass for individual strain were determined by HPLC and dry weight method. Titer of terrein were the mean of three biological replicates. ns. means no significance, *p ≤ 0.05 and **p ≤ 0.01

Substantially enhancement of terrein yield by deleting stuA

In addition to pathway-specific regulator, transcription of most of secondary metabolite gene clusters are also controlled by global regulators. These regulatory proteins not only involve in secondary metabolism, but also have roles in fungal growth, development, as well as primary metabolic process [20]. The APSES transcription factor StuA was previously known as the conserved morphological modifier, playing crucial roles in cellular differentiation, mycelial growth, as well as asexual and sexual development in filamentous fungi [21, 22]. Recent studies has suggested that StuA regulates biosynthesis of multiple SM gene clusters in different species [21, 23], implying that it might function as a global regulator of SM in fungi. We presumed that StuA might contribute to biosynthesis of terrein in A. terreus for its high transcription abundance during terrein inducing media. The stuA mutant has been established in our previous investigation [19], but its biological function remain unknown in A. terreus.

As in other filamentous fungi, there was little to no conidia could be observed in the ΔstuA mutant regardless of media used (Fig. 2), while WT produced abundant amounts of conidia on any medium. Unlike in other fungi, our results suggested that radial growth of the ΔstuA mutant was approximately 10% increased as compared with that of WT on PDA, GMM, and TFM. Interestingly, a pale yellow pigment was clearly observed in the ΔstuA mutant, especially on the TFM plate, but not in WT. Considering that multiple precursors in the terrein biosynthesis are yellow, it can be speculated that the terrein gene cluster was activated in the mutant. To investigate the effect of StuA on terrein production, both the ΔstuA mutant and WT strains were cultured in TPM media to induce terrein biosynthesis. The yield of terrein was detected at 5 day by HPLC. The results showed that the ΔstuA mutant produced 10.8 mg/ml terrein, which was 21 folds more than that of WT. These results showed that deletion of stuA greatly enhanced terrein production.

Construct a robust and high-producing cell factory for terrein synthesis by combing terR overexpression and stuA deletion

To further improve the terrein production, the pathway-specific transcription factor TerR and the global regulator StuA were simultaneously genetically modified in the marine-derived fungus A. terreus RA2905. The double gene mutant ΔstuA::OEterR were obtained by deletion of stuA in the OEterR-6 mutant with hph was used as the selectable marker gene described previously [19]. The resultant mutant ΔstuA::OEterR also lost the ability to develop conidia, which is the same as ΔstuA (Fig. 2), its terrein yield was further enhanced than that of ΔstuA or OEterR, reach the level of 12.6 g/L. More intriguingly, approximately 80% of fungal extract for ΔstuA::OEterR cultured in TFM media was terrein, which represent the highest yield to date.

Loss of StuA improve the biomass of A. terreus

To investigate the TerR and StuA on fungal growth under fermentation process, the biomass of the ΔstuA and OEterR mutants, as well as WT strains were analyzed by dry cell weight assay (DCW) (Fig. 3B). Considering that the ΔstuA mutant did not produce conidia, a shift experiment was designed to achieve the same initial inoculum dose. The results showed that two terR overexpression mutants develop the same biomass as that of WT, suggesting that TerR not involved in fungal growth. In contrast, the biomass of ΔstuA mutant (16 g/L) was significantly increased compared to WT (12 g/L), indicating that StuA play a negative regulatory role in fungal growth.

Expression analysis of terrein biosynthesis genes

Compared with the WT strain, a significant improvement in terrein yields was observed in OEterR, ΔstuA, ΔstuA::terR mutant mutants. We wondered whether this improvement was the result from up-regulation in gene transcription level. Therefore, the transcripts of the major terrein biosynthetic genes, including terA ~ terR, are analyzed by semi-quantitative PCR. Considering that no conidia were produced in ΔstuA or ΔstuA::terR, a shift experiment of mycelia was designed to ensure the same inoculation size and time among stuA mutants and WT. As expected, the results indicated that the transcript abundance of most of terrein biosynthetic genes were up-regulated significantly in both OEterR and ΔstuA mutant than that of WT under terrein induction media (Fig. 4), and the double mutant showed the highest expression level, which was consistent with terrein titer analysis above. These results demonstrated that all of these mutants improve the terrein production by upregulating the expression level of terrein biosynthetic genes.

Block the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolites in terrein-producing mutant

As a prolific producer in secondary metabolism, A. terreus wild type strain was reported to produce diverse secondary metabolites simultaneously. And, a variety of secondary metabolites, including butyrolactones, thiodiketopiperazine, and benzyl furanones and pyrones were isolated from the marine-derived A. terreus RA2905 [24, 25]. To determine the effect of terR overexpression, stuA deletion and combined mutation on the biosynthesis of other secondary metabolite, the extracts of OEterR, ΔstuA or ΔstuA::OEterR and WT were analyzed by LC–MS/MS (Fig. 5). The results further supported that the production of terrein in all mutants were enhanced, and ΔstuA::OEterR showed the highest yield, in turn by ΔstuA, and OEterR mutants. As expected, OEterR mutant produced comparable butyrolactones and other secondary metabolites as WT strain. Significantly, other secondary metabolites, specially butyrolactone, which was the major metabolite in WT, were completely abolished in ΔstuA or ΔstuA::OEterR. Therefore, ΔstuA::OEterR established here was a cell factory for robust and high-level producing terrein, which greatly reduced the following purification process.

Discussion

The A. terreus secondary metabolite terrein had been demonstrated to possess extensive biological and pharmacological benefits, including anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory and antimicrobial activities. Furthermore, Matthias Brock et al. has reported that the terrein gene cluster was a high-performance expression system for biosynthesizing other fungal secondary metabolites [26]. However, the terrein yield and expression level of terrein genes were relatively low in the wild type strain of A. terreus. Therefore, identification and engineering of critical factor for terrein production is essential for providing resource of pharmacological research, as well as developing the more efficient and robust expression platform of fungal secondary metabolite gene cluster.

The APSES transcription factor StuA was initially found to be a regulator of fungal asexual and sexual development [22]. Recently, its regulatory role in secondary metabolism has been revealed in several fungi [21, 23]. In general, StuA positively regulates the SM gene expression, and its deletion resulted in reduction or even absence of secondary metabolite biosynthesis, such as aflatoxin [21]. However, it was interestingly found that deletion of stuA in A. terreus lead to reduced biosynthesis of other secondary metabolism, such as butyrolactones, but increase terrein production. However, the underlying mechanism remain further investigation.

Biosynthesis of secondary metabolites are controlled by both global and pathway-specific regulators in fungi. Global regulators, such as methyltransferase LaeA, were mainly more conserved than that of these pathway-specific regulators in the regulation of secondary metabolism [27, 28]. However, it was found that these global regulators also interfere with primary metabolic process in fungi, such as growth and conidial development, which caused unexpected defects [29]. While pathway-specific regulators are confined to the given BGC in a species, its function was specialized, could not deter the primary metabolism, as well as other secondary metabolite biosynthesis. Furthermore, these global regulators have regulatory roles in the expression of pathway-specific transcription factors, which establish a regulatory cascade for accurately and sharply control the secondary metabolite production. Thus, interpretation and engineering of the pathway-specific and global regulators, as well as its relationship, were essential for developing the efficient cell factory for a given and valued secondary metabolite production. Only alteration of either was limited for SM production engineering. Here, the regulatory program was redesigned by combing the pathway-specific regulator terR overexpression and the global regulator stuA deletion, the double mutant produced about 30 folds more terrein than that of WT, achieving ten-gram-level fermentation production of the anti-cancer compound terrein.

In conclusion, a genetic roadmap for engineering terrein production was established by combing redesign of both global and pathway-specific regulators, greatly improve the terrein production, not only help deepen the understand of regulatory mechanism of secondary metabolism, but provide a paradigm for yield improvement of other valued secondary metabolites in A. terreus and other filamentous fungi.

Materials and methods

Strains, primers and media

Strains of marine-derived A. terreus used in this study were listed in Table 2. All A. terreus strains were cultured on PDA (potato broth 20% and glucose 2% in sea water) media for propagation. GMM (Czapek–Dox salt 2% and glucose 2% in sea water) supplemented with 1 M sorbitol were used to for protoplast regeneration, or supplemented o.5 mM uridine and 1 mM uracil if necessary. TFM (starch 3%, peptone 1.5% and aginomoto 0.5%) media was used to ferment production of terrein. A. terreus mutants and WT strains were grown on PDA, GMM and TFM media supplemented with 1.5% agar for growth and conidial development analysis.

Construction of mutants

To construct terR overexpression strains, open reading frame (ORF) and terminator of terR was amplified from A. terreus genomic DNA with primers GPDterRF and terR1. The constitutive promoter of gene gpdA from A. nidulans was amplified from plasmid pIG1783 with primer pair GPDF/ GPDR, and the selectable maker gene pyrG as amplified from A. fumigatus genomic DNA with primers PyrGF/PyrGR. The three fragments obtained above were fused by using Double-Joint PCR based on the homologous sequence in primers. Preparation of protoplast and transformation of A. terreus RA2905 were performed as established previously [19]. All primers used were listed in Table 3.

HPLC analysis of terrein

All strains were cultivated in TFM at 30 °C, 150 rpm for 7 days. The fungal cultures were extracted with ethyl acetate at least three times. HPLC analysis was performed on an Agilent InfinityLab LC Series 1260 system coupled with a Diode Array Detector WR detector and using an analytical Kromasil column (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 mm). The mobile phase was consisted of 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile (A) and 0.1% formic acid in water (B), and the flow rate was 1 mL/min with 10 μL injection volume. Terrein was recorded at 281 nm.

LC–MS analysis of secondary metabolites

LC–MS/MS were analyzed on a UHPLC system (1290, Agilent Technologies) with a UPLC HSS T3 column (1.8 μm 2.1 × 100 mm, Waters) coupled to a quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometer 6545 (Q-TOF, Agilent Technologies) equipped with an ESI dual source in positive-ion mode. The ESI conditions were as follows: the capillary temperature at 350 °C, source voltage at 4 kV, and a sheath gas flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The mass spectrometer was operated with an auto MS/MS mode. Mass spectra were recorded from m/z 200 to m/z 1000 in a speed of 6 spectra/sec, followed by MS/MS spectra of the twelve most intense ions from m/z 200 to m/z 1000 in a speed of 12 spectra/sec.

Gene expression analysis

All utilized A. terreus strains were inoculated into GMM liquid media and pre-cultured for 24 h, and then transferred into fresh LFM media at 28 °C for 48 h. The mycelia were collected via filtering, were then frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored under − 80 °C conditions. RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis were performed using a RNA reagent (TRIzol reagent, Biomarker Technologies, Beijing, China) and a cDNA synthesis Kit (TransGen, Beijing, China) following the protocols of the manufactures, respectively. The quality and integrity of RNA samples was determined using Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA), respectively, while the quantity was determined with a Qubit RNA assay kit (Life Invitrogen, USA). All utilized primers were listed in Table 3. The expression level of actin gene was used as the internal control.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated and analyzed during this study were included in this manuscript and the additional files.

Abbreviations

- gpdA:

-

Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- WT:

-

Wild type

- SM:

-

Secondary metabolism

- LS-MS/MS:

-

Liquid chromatography tandem-mass spectrometry

- QS:

-

Quorum sensing

- c-di-GMP:

-

Cyclic-di-GMP

- MDR:

-

Multidrug-resistant

- HR–ESI–MS:

-

High-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry

- NMR:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy

- HPLC:

-

High performance liquid chromatography

References

Park SH, Kim DS, Kim WG, Ryoo IJ, Lee DH, Huh CH, Youn SW, Yoo ID, Park KC. Terrein: a new melanogenesis inhibitor and its mechanism. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2004;61:2878–85.

Park SH, Kim DS, Lee HK, Kwon SB, Lee S, Ryoo IJ, Kim WG, Yoo ID, Park KC. Long-term suppression of tyrosinase by terrein via tyrosinase degradation and its decreased expression. Exp Dermatol. 2009;18:562–6.

Lee S, Kim WG, Kim E, Ryoo IJ, Lee HK, Kim JN, Jung SH, Yoo ID. Synthesis and melanin biosynthesis inhibitory activity of (+/-)-terrein produced by Penicillium sp. 20135. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2005;15:471–3.

Zhang F, Mijiti M, Ding W, Song J, Yin Y, Sun W, Li Z. (+)Terrein inhibits human hepatoma Bel7402 proliferation through cell cycle arrest. Oncol Rep. 2015;33:1191–200.

Kim DS, Lee HK, Park SH, Lee S, Ryoo IJ, Kim WG, Yoo ID, Na JI, Kwon SB, Park KC. Terrein inhibits keratinocyte proliferation via ERK inactivation and G2/M cell cycle arrest. Exp Dermatol. 2008;17:312–7.

Porameesanaporn Y, Uthaisang-Tanechpongtamb W, Jarintanan F, Jongrungruangchok S, Thanomsub Wongsatayanon B. Terrein induces apoptosis in HeLa human cervical carcinoma cells through p53 and ERK regulation. Oncol Rep. 2013;29:1600–8.

Liao WY, Shen CN, Lin LH, Yang YL, Han HY, Chen JW, Kuo SC, Wu SH, Liaw CC. Asperjinone, a nor-neolignan, and terrein, a suppressor of ABCG2-expressing breast cancer cells, from thermophilic Aspergillus terreus. J Nat Prod. 2012;75:630–5.

Lee YH, Lee SJ, Jung JE, Kim JS, Lee NH, Yi HK. Terrein reduces age-related inflammation induced by oxidative stress through Nrf2/ERK1/2/HO-1 signalling in aged HDF cells. Cell Biochem Funct. 2015;33:479–86.

Lee JC, Yu MK, Lee R, Lee YH, Jeon JG, Lee MH, Jhee EC, Yoo ID, Yi HK. Terrein reduces pulpal inflammation in human dental pulp cells. J Endod. 2008;34:433–7.

Kim KW, Kim HJ, Sohn JH, Yim JH, Kim YC, Oh H. Terrein suppressed lipopolysaccharide-induced neuroinflammation through inhibition of NF-kappaB pathway by activating Nrf2/HO-1 signaling in BV2 and primary microglial cells. J Pharmacol Sci. 2020;143:209–18.

Zaehle C, Gressler M, Shelest E, Geib E, Hertweck C, Brock M. Terrein biosynthesis in Aspergillus terreus and its impact on phytotoxicity. Chem Biol. 2014;21:719–31.

Goutam J, Sharma G, Tiwari VK, Mishra A, Kharwar RN, Ramaraj V, Koch B. Isolation and characterization of “Terrein” an antimicrobial and antitumor compound from endophytic fungus Aspergillus terreus (JAS-2) associated from Achyranthus aspera Varanasi India. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:1334.

Kim B, Park JS, Choi HY, Yoon SS, Kim WG. Terrein is an inhibitor of quorum sensing and c-di-GMP in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a connection between quorum sensing and c-di-GMP. Sci Rep. 2018;8:8617.

Gressler M, Meyer F, Heine D, Hortschansky P, Hertweck C, Brock M. Phytotoxin production in Aspergillus terreus is regulated by independent environmental signals. Elife. 2015;4:e07861.

Zhao C, Guo L, Wang L, Zhu G, Zhu W. Improving the yield of (+)-terrein from the salt-tolerant Aspergillus terreus PT06-2. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2016;32:77.

Xu B, Yin Y, Zhang F, Li Z, Wang L. Operating conditions optimization for (+)-terrein production in a stirred bioreactor by Aspergillus terreus strain PF-26 from marine sponge Phakellia fusca. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng. 2012;35:1651–5.

Yin Y, Ding Y, Feng G, Li J, Xiao L, Karuppiah V, Sun W, Zhang F, Li Z. Modification of artificial sea water for the mass production of (+)-terrein by Aspergillus terreus strain PF26 derived from marine sponge Phakellia fusca. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2015;61:580–7.

Yin Y, Xu B, Li Z, Zhang B. Enhanced production of (+)-terrein in fed-batch cultivation of Aspergillus terreus strain PF26 with sodium citrate. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;29:441–6.

Yao G, Chen X, Han Y, Zheng H, Wang Z, Chen J. Development of versatile and efficient genetic tools for the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus RA2905. Curr Genet. 2022;68:153–64.

Macheleidt J, Mattern DJ, Fischer J, Netzker T, Weber J, Schroeckh V, Valiante V, Brakhage AA. Regulation and role of fungal secondary metabolites. Annu Rev Genet. 2016;50:371–92.

Yao G, Zhang F, Nie X, Wang X, Yuan J, Zhuang Z, Wang S. Essential APSES transcription factors for mycotoxin synthesis, fungal development, and pathogenicity in Aspergillus flavus. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2277.

Zhao Y, Su H, Zhou J, Feng H, Zhang KQ, Yang J. The APSES family proteins in fungi: characterizations, evolution and functions. Fungal Genet Biol. 2015;81:271–80.

Rath M, Crenshaw NJ, Lofton LW, Glenn AE, Gold SE. FvSTUA is a key regulator of sporulation, toxin synthesis, and virulence in Fusarium verticillioides. Mol Plant Microbe Interact. 2020;33:958–71.

Wu JS, Shi XH, Zhang YH, Shao CL, Fu XM, Li X, Yao GS, Wang CY. Benzyl furanones and pyrones from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus induced by chemical epigenetic modification. Molecules. 2020;25(17):3927.

Wu JS, Shi XH, Yao GS, Shao CL, Fu XM, Zhang XL, Guan HS, Wang CY. New thiodiketopiperazine and 3,4-dihydroisocoumarin derivatives from the marine-derived fungus Aspergillus terreus. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(3):132.

Gressler M, Hortschansky P, Geib E, Brock M. A new high-performance heterologous fungal expression system based on regulatory elements from the Aspergillus terreus terrein gene cluster. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:184.

Cheng M, Zhao S, Lin C, Song J, Yang Q. Requirement of LaeA for sporulation, pigmentation and secondary metabolism in Chaetomium globosum. Fungal Biol. 2021;125:305–15.

Khan I, Xie WL, Yu YC, Sheng H, Xu Y, Wang JQ, Debnath SC, Xu JZ, Zheng DQ, Ding WJ, Wang PM. Heteroexpression of Aspergillus nidulans laeA in marine-derived fungi triggers upregulation of secondary metabolite biosynthetic genes. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(12):652.

Zhu C, Wang Y, Hu X, Lei M, Wang M, Zeng J, Li H, Liu Z, Zhou T, Yu D. Involvement of LaeA in the regulation of conidia production and stress responses in Penicillium digitatum. J Basic Microbiol. 2020;60:82–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank Prof Chang-Yun Wang (Ocean University of China) for providing fungal strain. We also thank a lot for Yao-Yao Zheng and Zhipu Yu from Ocean University of China for his excellent technical assistance.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundations of China (32100059), Natural Science Foundation of Fujian Province (2021J011043), and Department of Natural Resources of Fujian Province (KY-090000-04-2021-002), grants from Minjiang University (MYK19011 and JAT190622) and Key Laboratory of Pathogenic Fungi and Mycotoxins of Fujian Province (Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YGS conceived the project, analyzed results and write the manuscript. ZBX, WL and BXF contributed to methodology and data curation, WZH and CSB reviewed and edited the manuscript, YGS, WL and CSB, funding acquisition. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Determine the structure of terrain. Figure S1. 1H NMR of terrain. Figure S2. 13C NMR of terrain.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yao, G., Bai, X., Zhang, B. et al. Enhanced production of terrein in marine-derived Aspergillus terreus by refactoring both global and pathway-specific transcription factors. Microb Cell Fact 21, 136 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-022-01859-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12934-022-01859-5