Abstract

Background

Since the triglyceride glucose (TyG) index can reflect insulin resistance, it has been proven to be an efficient predictor of glycolipid-metabolism-related diseases. Therefore, this study aimed to investigate the predictive value of the TyG index for visceral obesity (VO) and body fat distribution in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM).

Methods

Abdominal adipose tissue characteristics in patients with T2DM, including visceral adipose area (VAA), subcutaneous adipose area (SAA), VAA-to-SAA ratio (VSR), visceral adipose density (VAD), and subcutaneous adipose density (SAD), were obtained through analyses of computed tomography images at the lumbar 2/3 level. VO was diagnosed according to the VAA (> 142 cm2 for males and > 115 cm2 for females). Logistic regression was performed to identify independent factors of VO, and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to compare the diagnostic performance according to the area under the ROC curve (AUC).

Results

A total of 976 patients were included in this study. VO patients showed significantly higher TyG values than non-VO patients in males (9.74 vs. 8.88) and females (9.59 vs. 9.01). The TyG index showed significant positive correlations with VAA, SAA, and VSR and negative correlations with VAD and SAD. The TyG index was an independent factor for VO in both males (odds ratio [OR] = 2.997) and females (OR = 2.233). The TyG index ranked second to body mass index (BMI) for predicting VO in male (AUC = 0.770) and female patients (AUC = 0.720). Patients with higher BMI and TyG index values showed a significantly higher risk of VO than the other patients. TyG-BMI, the combination index of TyG and BMI, showed significantly higher predictive power than BMI for VO in male patients (AUC = 0.879 and 0.835, respectively) but showed no significance when compared with BMI in female patients (AUC = 0.865 and 0.835, respectively).

Conclusions

. TyG is a comprehensive indicator of adipose volume, density, and distribution in patients with T2DM and is a valuable predictor for VO in combination with anthropometric indices, such as BMI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), a complex endocrine-metabolic disease driven by a chronic positive energy balance, has become a major global public health crisis globally [1]. From 2000 to 2021, there was a 2.5-fold increase in the prevalence of T2DM worldwide, which is largely attributed to the obesity epidemic [2, 3]. Obesity, especially visceral obesity (VO), is an independent risk factor for T2DM, its complications and even all-cause mortality [4, 5].

Although body mass index (BMI) might be a convenient and simple index to monitor the growth in obesity prevalence at the population level, studies have shown that obesity defined by BMI cannot account for the extreme variation in intra-visceral fat distribution between individuals [6]. Furthermore, excessive visceral adipose tissue (VAT) accumulation is associated with endocrine system dysfunction and pro-inflammatory activity, which may contribute to the deterioration of insulin resistance and the development of vascular complications [7,8,9,10]. In contrast, subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) is reported as a weaker indicator of metabolic diseases [6, 11]. Therefore, an accurate assessment of the fat type is integral to understanding obesity-related comorbidities and the treatment of obesity.

Computed tomography (CT) is considered the gold standard for independently assessing visceral and subcutaneous abdominal fat mass [12]. In addition, CT can also evaluate fat density using radiographic pixels denoted in Hounsfield units (HU) and referred to as attenuation. A study evaluated 1829 Framingham Heart Study participants and found that lower abdominal fat density (more negative CT fat attenuation) is associated with adverse cardiometabolic risk [13]. However, because this method is expensive and requires radiation exposure, it is unsuitable for routine clinical practice in the general population [14].

The triglyceride glucose (TyG) index, which is calculated using triglyceride (TG) and fasting blood glucose (FBG), has become an attractive option for predicting insulin resistance [15]. It was first used by Simental-Mendia et al. 2008 [16]. Several recent studies have indicated that the TyG index is associated with inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, glucolipid metabolism disorders, thrombosis, and atherosclerotic disease[17,18,19]. Notably, the TyG index-related parameters, such as TyG-BMI, TyG-waist circumference (WC), and TyG-waist hip rate (WHR), showed higher predictive power for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease in Asians [20, 21]. Unfortunately, the correlation between the TyG index and VO, which is the main cause of insulin resistance in T2DM patients, remains unknown.

Therefore, in this study, we aimed to investigate whether the TyG index can adequately assess the fat distribution and predict VO in patients with T2DM.

Methods

Study population

T2DM patients hospitalized in the Department of Endocrinology, Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University, From January 2017–December 2021, were included in this study. All patients underwent CT scans, including the center plane of the third lumbar vertebra on axial images and blood analyses to determine FBG and TG levels. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) missing the major anthropometric measures, such as height and weight; (2) patients with malignant tumors, hepatic damage, immune disease, abnormal thyroid function, or stage V diabetic nephropathy; and (3) patients with acute complications or infections. On admission, all patients were informed that their medical records could be used for research unless they indicated their opposition. In the present study, none of the patients indicated opposition. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University (No. 2021C041).

Laboratory and anthropometric measurements

All biochemical and immune indices in the present study were measured at our hospital laboratory. FBG and TG levels were measured using an automatic analyzer (Cobas8000; Roche Diagnostics Ltd., Basel, Switzerland). The TyG index was calculated as the natural logarithm (Ln) of [TG (mg/dl) × FBG (mg/dl)/2]. The TyG-BMI, TyG-WC and TyG-WHR were calculated as TyG multiplied by BMI, WC and WHR, respectively. Both systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured using a sphygmomanometer after at least 5 min of seated rest. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated by dividing the body weight in kilograms by height in meters squared.

Measurement of abdominal adipose fat area

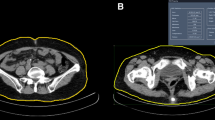

Abdominal CT was performed using a Dual-Source Flash CT scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). Two authors identified axial CT images at the L3 level, where the spinous and two transverse processes could be visualized. Abdominal adipose fat was assessed using abdominal axial CT images at the L3 level and Slice-O-Matic software (V.5.0, TomoVision, Montreal, Quebec, Canada), as described in our previous study [14]. The CT attenuation thresholds ranged from − 150 to -30 HU for VAT and from − 190 to -30 HU for SAT [22]. The visceral adipose area (VAA), subcutaneous adipose area (SAA), visceral adipose density (VAD), and subcutaneous adipose density (SAD) were automatically calculated by the software and shown as square centimeter and the mean radiation attenuation of adipose tissue in HU. VO was diagnosed according to Huo’s criteria: a VAA > 142 cm2 for men and > 115 cm2 for women at the L2/3 level [14, 23]. The VAA-to-SAA ratio (VSR) was calculated by dividing the area of VAT by that of SAT.

Definitions and diagnosis

Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg, and the use of antihypertensive medications. Dyslipidemia was defined as a disorder of lipoprotein metabolism and the use of lipid medications. Alcohol intake was defined as the consumption of at least 30 g of alcohol per week for at least a year. Cigarette smoking was defined as smoking at least 100 cigarettes in a lifetime [24].

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables are summarized using the median and interquartile range if not normally distributed and the mean ± SD if normally distributed. Categorical variables were summarized as frequency counts and percentages. These variables were compared between the two groups using an independent samples t-test or Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical variables were analyzed using the χ2 test. Univariable correlations between variables were assessed using Pearson’s correlation coefficients. Variables with significant differences between the VO and non-VO groups were enrolled in the logistic regression analysis to identify independent factors of VO. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analyses were used to compare the diagnostic performance of the independent factors for VO according to the area under the ROC curve (AUC). The overall predictive power for VO was further analyzed by comparing their AUCs using the Z test [25]. Since WC and WHR were extracted from only a limited number of patients, their correlations with VAA and diagnostic performance for VO were presented as additional analysis. The Statistical analysis was performed using the SPSS software V.25.0 (IBMCorp., Armonk, N.Y., USA). A two-tailed statistical measure with a p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Clinical characteristics of enrolled patients

A total of 976 patients (614 men and 362 women) were enrolled in this study. Their adipose tissue and clinical characteristics are shown in Tables 1 and 2. There was an obvious difference in the adipose tissue phenotype between male and female patients. Male patients showed a higher level of VAA (168.14 cm2 vs. 116.10 cm2) but a lower level of SAA (131.05 cm2 vs. 153.51 cm2) than female patients.

Except for higher areas of visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissues, VO patients showed higher levels of VSR and lower levels of VAD and SAD. Regarding other clinical features, VO patients showed higher BMI, SBP, DBP, hemoglobin, creatinine, alanine transaminase, TG, FBG and TyG index levels and higher percentages of dyslipidemia and hypertension. On an individual level, patients with the same BMI may have a different level of VAA. As shown in Fig. 1, patient A had a similar BMI to patient B but much higher levels of VAA.

Correlations between adipose tissue and clinical characteristics

The correlations between adipose tissue and other clinical characteristics are shown in Fig. 2. In males, the TyG index was significantly correlated with VAA (r = 0.380), SAA (r = 0.258), VAD (r =-0.403), and SAD (r =-0.249). In females, the TyG index showed similar significant correlations with VAA (r = 0.365), SAA (r = 0.172), and VAD (r =-0.296) but was not significantly correlated with SAD (r =-0.084). Generally, the TyG index ranked second only to BMI on the degree of correlation with the above adipose indices. It is worth noting that the TyG index showed a stronger correlation with VSR than BMI in both males (r = 0.228 vs. 0.137) and females (r = 0.296 vs. 0.111).

Correlations between adipose tissue and clinical characteristics. (A) male patients; (B) female patients. Abreviations: SBP, Systolic blood pressure; DBP, Diastolic blood pressure; Hb, hemoglobin; ALB, Albumin; ALT, alanine transaminase; Cr, creatinine; BUN, Blood urea nitrogen; TG, triglyceride; TC, Total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoproteins; LDL, low-density lipoproteins; FT3, free triiodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; FBG, fasting blood glucose; TyG, triglyceride glucose index; VAA, visceral adipose area; SAA, subcutaneous adipose area; VSR, VAA-to-SAA ratio; VAD, visceral adipose density; SAD, subcutaneous adipose density. ALT and TG were log-transformed in the analysis

Predictive ability of TyG index

Logistic regression analysis demonstrated that BMI and TyG index were independent factors associated with VO in both males (odds ratio [OR] = 1.580 and 2.997, respectively) and females (OR = 1.589 and 2.233, respectively) (Fig. 3). For the prediction of VO, both BMI and TyG index had acceptable powers in male (AUC = 0.835 and 0.770, respectively) and female patients (AUC = 0.835 and 0.720, respectively) (Fig. 4). In male and female patients, the cut-off values of BMI were 24.92 kg/m2 and 24.05 kg/m2, and of TyG index were 8.91 and 9.07, respectively (Fig. 4).

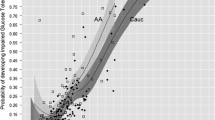

The scatter plot demonstrates the distribution of VO and non-VO patients according to their BMI and TyG index (Fig. 5). The patients were classified according to the cutoff values of BMI and TyG index. Patients with higher values of both BMI and TyG index showed a significantly higher risk of VO than the other patients. The adipose tissue and clinical characteristics of patients with different BMI and TyG index levels were shown in Supplemental Tables. The patients with higher BMI and TyG index levels had more severe disorders of glucolipid metabolism and adipose distribution.

As shown in Fig. 6, TyG-BMI, the combination index of TyG and BMI, showed significantly higher predictive power (AUC = 0.879) than BMI (AUC = 0.835) and TyG (AUC = 0.770) for VO in male patients. In female patients, TyG-BMI also showed significantly higher predictive power (AUC = 0.865) than TyG (AUC = 0.720) but showed no significance when compared with BMI (AUC = 0.835).

Addition analysis of WC and WHR in partial patients

Only 218 patients (125 men and 93 women) have the recorder of WC and WHR. Among all variables, WC showed the highest correlation with VAA in males (r = 0.746) and females (r = 0.716). As shown in Supplemental Fig. 1, WC showed strong predictive power for VO in males (AUC = 0.831) and females (AUC = 0.896). TyG-WC, the combination index of TyG and WC, showed higher diagnostic performance for VO in males (AUC = 0.860) but not in females (AUC = 0.890).

Discussion

In this study, we demonstrated an association between VO and the TyG index in patients with T2DM. The TyG index is a more efficient predictor of VO in individuals with T2DM than other biochemical indicators. The statistical cut-off value of the TyG index was 8.91 in males and 9.07 in females for VO prediction. These findings are clinically relevant because VO is an important health issue that needs to be detected early. However, current equipment is unsuitable for screening at the population level in primary care. According to our study, patients with higher values of both BMI (>24.92 kg/m2 in males, >24.05 kg/m2 in females, respectively) and TyG index (>8.91 in males, >9.07 in females, respectively) are more likely to have VO, which means that further examination is warranted.

Several anthropometric indices for visceral fat have been developed, such as BMI, WC, and WHR [26]. As biochemical indicators were not considered, these anthropometric indices alone cannot adequately assess central abdominal fat mass. They do not account for the extreme variation in visceral fat distribution between individuals [27]. At a given BMI or WC, Asians are characterized by a greater amount of VAT than Europeans [28]. Given the frequent coexistence of excess visceral and liver fat, the so-called hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype (high levels of TG and WC) has been developed as a tool to screen for the presence of excess VAT [29,30,31]. However, whether TG is the best indicator for predicting VO combined with WC or BMI has not been explored. Our study demonstrated that the TyG index has a more powerful predictive ability for VO than any other biochemical index.

In studies in Asians, TyG index-related parameters, including TyG-BMI, TyG-WC and TyG-WHR, showed higher predictive power for non-alcoholic fatty liver disease [20, 21]. Given the possibility that fatty liver reflects insulin resistance, we compared the overall predictive power of TyG-BMI with BMI. Our study demonstrated TyG-BMI had a higher diagnostic performance for VO than BMI in patients with T2DM. Therefore, TyG, combined with BMI, can improve the early diagnosis of VO and help the clinician develop more appropriate interventions to prevent or delay metabolic complications.

The distribution of adipose tissue also plays a crucial role in the progression of T2DM and its vascular complications [32]. Visceral and ectopic adiposity confer a much higher risk of cardiovascular disease than subcutaneous adiposity [33]. Large cohort studies have documented excess VAT as a predictor of the development of cardiovascular risk factors over time, independent of total body fat mass or subcutaneous adipose tissue levels [34, 35]. Lower abdominal fat density is also associated with the profile of biomarkers and may be a valid biomarker of cardiometabolic risk [13]. In some studies, VSR has been reported to be more strongly associated with cardiometabolic risks than VAA [36,37,38,39,40]. Therefore, except VAA, both VSR and VAD are also important indicators for cardiometabolic diseases. The present study demonstrated that the TyG index is significantly correlated with VAD and has a stronger correlation with VSR than BMI, which has also been confirmed in the PREDIMED-Plus trial [41]. This evidence indicated that the TyG index is a more comprehensive indicator of adipose volume, density, and distribution.

Several studies have confirmed the association between the TyG index and metabolic diseases such as metabolic syndrome, diabetes, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and cardiovascular disease [42,43,44,45,46,47]. The cut-off values of the TyG index were 8.7 for the prevalence of metabolic syndrome [42], 8.5 for NAFLD [47], and 9.3 for major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes [43]. These values are close to 9 and are consistent with the cut-off values of VO in this study. The consistency of the cutoff values for the TyG index in predicting these metabolic diseases may be attributed to the insulin resistance induced by VO.

Several pieces of evidence have suggested strong sex specificity for regional adipose tissue distributions, with females having a higher proportion of gluteal-femoral body (subcutaneous) fat; however, males have more in the abdominal (visceral) region [48, 49]. Similar to the above studies, our study also observed that males have a much higher level of visceral adipose, and females have more subcutaneous fat. This obvious difference in the adipose tissue phenotype according to sex is partially because of sex hormones and genetic variations [50].

This study has several limitations. First, more than 80% of the patients were under antidiabetic treatment, nearly 20% of the patients received statins, and a few subjects took fibrates, which inevitably affected the stability of our results. Second, we continuously collected data from all participants at a particular location over time; thus, our participants represent hospitalized patients with T2DM but not the general population with T2DM. Third, only 25% of included patients had a record of WC and WHR. The predictive ability of TyG, in combination with these anthropometric indices for VO, needs to be confirmed by further large sample studies. Fourth, the predictive ability of HOMA-IR for VO was not compared because serum C-peptide and insulin were susceptible to antidiabetic drugs and not routine inspection items in our hospital. Finally, because our study was conducted in Chinese adults with T2DM, the findings may not be readily generalizable to other populations or ethnicities.

In conclusion, we showed a significant association between an increased TyG index and VO in patients with T2DM. The TyG index is a comprehensive indicator of adipose volume, density, and distribution in patients with T2DM. It is a valuable predictor of VO in combination with anthropometric indices, such as BMI.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Further inquiries for the original data can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Abbreviations

- ALT:

-

Alanine transaminase

- ALB:

-

Albumin

- AUC:

-

Area under the ROC curve

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- Cr:

-

Creatinine

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- FBG:

-

Fasting blood glucose

- FT4:

-

Free thyroxine

- FT3:

-

Free triiodothyronine

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- Hb:

-

Hemoglobin

- HbA1c:

-

Glycated hemoglobin

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoproteins

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoproteins

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SAA:

-

Subcutaneous adipose area

- SAD:

-

Subcutaneous adipose density

- SAT:

-

Subcutaneous adipose tissue

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- TSH:

-

Thyroid-stimulating hormone

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TyG:

-

Triglyceride glucose

- T2DM:

-

Type 2 diabetes mellitus

- VSR:

-

VAA-to-SAA ratio

- VAA:

-

Visceral adipose area

- VAD:

-

Visceral adipose density

- VAT:

-

Visceral adipose tissue

- VO:

-

Visceral obesity

- WC:

-

Waist circumference

- WHR:

-

Waist hip rate

References

Ahmad E, Lim S, Lamptey R, Webb DR, Davies MJ. Type 2 diabetes. Lancet. 2022;400(10365):1803–20.

Magliano DJ, Boyko EJ. committee IDFDAtes: IDF Diabetes Atlas. In: Idf diabetes atlas Brussels: International Diabetes Federation © International Diabetes Federation, 2021.; 2021.

Longo M, Zatterale F, Naderi J, Parrillo L, Formisano P, Raciti GA, Beguinot F, Miele C. Adipose Tissue Dysfunction as Determinant of Obesity-Associated Metabolic Complications. Int J Mol Sci 2019, 20(9).

Jensen MD. Visceral Fat: culprit or Canary? Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2020;49(2):229–37.

Lee SW, Son JY, Kim JM, Hwang SS, Han JS, Heo NJ. Body fat distribution is more predictive of all-cause mortality than overall adiposity. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(1):141–7.

Neeland IJ, Ross R, Després JP, Matsuzawa Y, Yamashita S, Shai I, Seidell J, Magni P, Santos RD, Arsenault B, et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(9):715–25.

Moh A, Neelam K, Zhang X, Sum CF, Tavintharan S, Ang K, Lee SBM, Tang WE, Lim SC. Excess visceral adiposity is associated with diabetic retinopathy in a multiethnic asian cohort with longstanding type 2 diabetes. Endocr Res. 2018;43(3):186–94.

Xu L, Song P, Xu J, Zhang H, Yu C, Guan Q, Zhao M, Zhang X. Viscus fat area contributes to the Framingham 10-year general cardiovascular disease risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Life Sci. 2019;220:69–75.

Omura-Ohata Y, Son C, Makino H, Koezuka R, Tochiya M, Tamanaha T, Kishimoto I, Hosoda K. Efficacy of visceral fat estimation by dual bioelectrical impedance analysis in detecting cardiovascular risk factors in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):137.

Wang Y, Chen F, Wang J, Wang T, Zhang J, Han Q, Wu Y, Zhang R, Liu F. The relationship between increased ratio of visceral-to-Subcutaneous Fat Area and Renal Outcome in chinese adults with type 2 diabetes and Diabetic kidney disease. Can J Diabetes. 2019;43(6):415–20.

Wan H, Wang Y, Xiang Q, Fang S, Chen Y, Chen C, Zhang W, Zhang H, Xia F, Wang N, et al. Associations between abdominal obesity indices and diabetic complications: chinese visceral adiposity index and neck circumference. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19(1):118.

Park HJ, Shin Y, Park J, Kim H, Lee IS, Seo DW, Huh J, Lee TY, Park T, Lee J, et al. Development and validation of a deep learning system for segmentation of abdominal muscle and Fat on Computed Tomography. Korean J Radiol. 2020;21(1):88–100.

Lee JJ, Pedley A, Hoffmann U, Massaro JM, Keaney JF Jr, Vasan RS, Fox CS. Cross-sectional Associations of computed tomography (CT)-Derived adipose tissue density and adipokines: the Framingham Heart Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(3):e002545.

Yang Q, Zhang M, Sun P, Li Y, Xu H, Wang K, Shen H, Ban B, Liu F. Cre/CysC ratio may predict muscle composition and is associated with glucose disposal ability and macrovascular disease in patients with type 2 diabetes. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care 2021, 9(2).

Sánchez-García A, Rodríguez-Gutiérrez R, Mancillas-Adame L, González-Nava V, Díaz González-Colmenero A, Solis RC, Álvarez-Villalobos NA, González-González JG. Diagnostic accuracy of the triglyceride and glucose index for insulin resistance: a systematic review. Int J Endocrinol. 2020;2020. 4678526.

Simental-Mendía LE, Rodríguez-Morán M, Guerrero-Romero F. The product of fasting glucose and triglycerides as surrogate for identifying insulin resistance in apparently healthy subjects. Metab Syndr Relat Disord. 2008;6(4):299–304.

Zhao J, Fan H, Wang T, Yu B, Mao S, Wang X, Zhang W, Wang L, Zhang Y, Ren Z, et al. TyG index is positively associated with risk of CHD and coronary atherosclerosis severity among NAFLD patients. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):123.

Park B, Lee HS, Lee YJ. Triglyceride glucose (TyG) index as a predictor of incident type 2 diabetes among nonobese adults: a 12-year longitudinal study of the korean genome and epidemiology study cohort. Transl Res. 2021;228:42–51.

Chamroonkiadtikun P, Ananchaisarp T, Wanichanon W. The triglyceride-glucose index, a predictor of type 2 diabetes development: a retrospective cohort study. Prim Care Diabetes. 2020;14(2):161–7.

Sheng G, Lu S, Xie Q, Peng N, Kuang M, Zou Y. The usefulness of obesity and lipid-related indices to predict the presence of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2021;20(1):134.

Otsubo N, Fukuda T, Genhin C, Ishibashi F, Yamada T, Monzen K. Utility of Indices Obtained During Medical Checkups for Predicting Fatty Liver Disease in Non-obese People. Internal medicine (Tokyo, Japan) 2022.

Albersheim J, Sathianathen NJ, Zabell J, Renier J, Bailey T, Hanna P, Konety BR, Weight CJ. Skeletal muscle and Fat Mass indexes predict Discharge Disposition after Radical Cystectomy. J Urol. 2019;202(6):1143–9.

Huo L, Li K, Deng W, Wang L, Xu L, Shaw JE, Jia P, Zhou D, Cheng XG. Optimal cut-points of visceral adipose tissue areas for cardiometabolic risk factors in a chinese population: a cross-sectional study. Diabet Med. 2019;36(10):1268–75.

Xu S, Ming J, Jia A, Yu X, Cai J, Jing C, Liu C, Ji Q. Normal weight obesity and the risk of diabetes in chinese people: a 9-year population-based cohort study. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):6090.

Park SH, Goo JM, Jo CH. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve: practical review for radiologists. Korean J Radiol. 2004;5(1):11–8.

Fang H, Berg E, Cheng X, Shen W. How to best assess abdominal obesity. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018;21(5):360–5.

Neeland IJ, Poirier P, Després JP. Cardiovascular and metabolic heterogeneity of obesity: Clinical Challenges and Implications for Management. Circulation. 2018;137(13):1391–406.

Du T, Sun X, Huo R, Yu X. Visceral adiposity index, hypertriglyceridemic waist and risk of diabetes: the China Health and Nutrition Survey 2009. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(6):840–7.

Tian YM, Ma N, Jia XJ, Lu Q. The “hyper-triglyceridemic waist phenotype” is a reliable marker for prediction of accumulation of abdominal visceral fat in chinese adults. Eat Weight Disord. 2020;25(3):719–26.

Cunha de Oliveira C, Carneiro Roriz AK, Eickemberg M, Barreto Medeiros JM, Barbosa Ramos L. Hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype: association with metabolic disorders and visceral fat in adults. Nutr Hosp. 2014;30(1):25–31.

Sam S, Haffner S, Davidson MH, D’Agostino RB, Sr., Feinstein S, Kondos G, Perez A, Mazzone T. Hypertriglyceridemic waist phenotype predicts increased visceral fat in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(10):1916–20.

Wu Z, Yu S, Kang X, Liu Y, Xu Z, Li Z, Wang J, Miao X, Liu X, Li X, et al. Association of visceral adiposity index with incident nephropathy and retinopathy: a cohort study in the diabetic population. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):32.

Piché ME, Tchernof A, Després JP. Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and Cardiovascular Diseases. Circ Res. 2020;126(11):1477–500.

Abraham TM, Pedley A, Massaro JM, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. Association between visceral and subcutaneous adipose depots and incident cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circulation. 2015;132(17):1639–47.

Liu J, Fox CS, Hickson DA, May WD, Hairston KG, Carr JJ, Taylor HA. Impact of abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue on cardiometabolic risk factors: the Jackson Heart Study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(12):5419–26.

Kim S, Cho B, Lee H, Choi K, Hwang SS, Kim D, Kim K, Kwon H. Distribution of abdominal visceral and subcutaneous adipose tissue and metabolic syndrome in a korean population. Diabetes Care. 2011;34(2):504–6.

Kaess BM, Pedley A, Massaro JM, Murabito J, Hoffmann U, Fox CS. The ratio of visceral to subcutaneous fat, a metric of body fat distribution, is a unique correlate of cardiometabolic risk. Diabetologia. 2012;55(10):2622–30.

Katsuyama H, Kawaguchi A, Yanai H. Not visceral fat area but the ratio of visceral to subcutaneous fat area is significantly correlated with the marker for atherosclerosis in obese subjects. Int J Cardiol. 2015;179:112–3.

Narumi H, Yoshida K, Hashimoto N, Umehara I, Funabashi N, Yoshida S, Komuro I. Increased subcutaneous fat accumulation has a protective role against subclinical atherosclerosis in asymptomatic subjects undergoing general health screening. Int J Cardiol. 2009;135(2):150–5.

Fukuda T, Bouchi R, Takeuchi T, Nakano Y, Murakami M, Minami I, Izumiyama H, Hashimoto K, Yoshimoto T, Ogawa Y. Ratio of visceral-to-subcutaneous fat area predicts cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes. J diabetes Invest. 2018;9(2):396–402.

Konieczna J, Abete I, Galmés AM, Babio N, Colom A, Zulet MA, Estruch R, Vidal J, Toledo E, Díaz-López A, et al. Body adiposity indicators and cardiometabolic risk: cross-sectional analysis in participants from the PREDIMED-Plus trial. Clin Nutr. 2019;38(4):1883–91.

Son DH, Lee HS, Lee YJ, Lee JH, Han JH. Comparison of triglyceride-glucose index and HOMA-IR for predicting prevalence and incidence of metabolic syndrome. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2022;32(3):596–604.

Wang L, Cong HL, Zhang JX, Hu YC, Wei A, Zhang YY, Yang H, Ren LB, Qi W, Li WY, et al. Triglyceride-glucose index predicts adverse cardiovascular events in patients with diabetes and acute coronary syndrome. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19(1):80.

Navarro-González D, Sánchez-Íñigo L, Pastrana-Delgado J, Fernández-Montero A, Martinez JA. Triglyceride-glucose index (TyG index) in comparison with fasting plasma glucose improved diabetes prediction in patients with normal fasting glucose: the vascular-metabolic CUN cohort. Prev Med. 2016;86:99–105.

Ding X, Wang X, Wu J, Zhang M, Cui M. Triglyceride-glucose index and the incidence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20(1):76.

Tao LC, Xu JN, Wang TT, Hua F, Li JJ. Triglyceride-glucose index as a marker in cardiovascular diseases: landscape and limitations. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2022;21(1):68.

Zhang S, Du T, Zhang J, Lu H, Lin X, Xie J, Yang Y, Yu X. The triglyceride and glucose index (TyG) is an effective biomarker to identify nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Lipids Health Dis. 2017;16(1):15.

Blaak E. Gender differences in fat metabolism. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2001;4(6):499–502.

Zillikens MC, Yazdanpanah M, Pardo LM, Rivadeneira F, Aulchenko YS, Oostra BA, Uitterlinden AG, Pols HA, van Duijn CM. Sex-specific genetic effects influence variation in body composition. Diabetologia. 2008;51(12):2233–41.

Li H, Konja D, Wang L, Wang Y. Sex Differences in Adiposity and Cardiovascular Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23(16).

Acknowledgements

We thank editage (www.editage.cn) for its linguistic assistance during the preparation of this manuscript. We thank Shanghai Tengyun Biotechnology Co., Ltd. for developing Hiplot Pro platform (https://hiplot.com.cn/) and providing technical assistance and valuable tools for data analysis and visualization.

Funding

The study was supported by the Research Fund for Lin He’s Academician Workstation of New Medicine and Clinical Translation in Jining Medical University (JYHL2021FMS11), the Key Research and Development Project of Jining City (2021YXNS073) and Postdoctoral Program of Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University (JYFY322154).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

The study was conceived by Q.Y and F.L, with manuscript questions and analytic plan designed by Q.Y, H.Z, M.Z, and F.L. F.L and Q.Y drafted the manuscript. F.L, Q.Y, D.H, S.C and Y.L interpreted the data, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript. H.X, B.B and G.Y reviewed the manuscript. All authors had access to the data and all authors agreed to submit the final manuscript. Q.Y and F.L were the guarantors of this work and as such have full access to all the data in the study as well as take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Affiliated Hospital of Jining Medical University (No. 2021C041). All patients were informed at admission that their medical records may be used for research purposes unless they indicated their opposition. For the present study, no patient indicated opposition.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12933_2023_1834_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Supplemental Table 1. The adipose tissue and clinical characteristics of male patients with different levels of BMI and TyG index

Supplemental Table 2. The adipose tissue and clinical characteristics of female patients with different levels of BMI and TyG index

Supplemental Fig. 1. ROC analyses of TyG-WC and TyG-WHR for VO (A) male patients; (B) female patients

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, Q., Xu, H., Zhang, H. et al. Serum triglyceride glucose index is a valuable predictor for visceral obesity in patients with type 2 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 22, 98 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01834-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-023-01834-3