Abstract

Background

Patients with Diabetes mellitus (DM) are susceptible to coronary artery disease (CAD). However, the impact of DM on plaque progression in the non-stented segments of stent-implanted patients has been rarely reported. This study aimed to evaluate the impact of DM on the prevalence, characteristics and severity of coronary computed tomography angiography (CCTA) verified plaque progression in stented patients. A comparison between diabetic and non-diabetic patients was performed.

Methods

A total of 98 patients who underwent clinically indicated serial CCTAs arranged within 1 month before and at least 6 months after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) were consecutively included. All the subjects were categorized into diabetic group (n = 36) and non-diabetic groups (n = 62). Coronary stenosis extent scores, segment involvement scores (SIS), segment stenosis scores (SSS) at baseline and follow-up CCTA were quantitatively assessed. The prevalence, characteristics and severity of plaque progression was evaluated blindly to the clinical data and compared between the groups.

Results

During the median 1.5 year follow up, a larger number of patients (72.2% vs 40.3%, P = 0.002), more non-stented vessels (55.7% vs 23.2%, P < 0.001) and non-stented segments (10.3% vs 4.4%, P < 0.001) showed plaque progression in DM group, compared to non-DM controls. More progressive lesions in DM patients were found to be non-calcified plaques (31.1% vs 12.8%, P = 0.014) or non-stenotic segments (6.6% vs 3.0%, p = 0.005) and were more widely distributed on left main artery (24.2% vs 5.2%, p = 0.007), the right coronary artery (50% vs 21.1%, P = 0.028) and the proximal left anterior artery (33.3% vs 5.1%, P = 0.009) compared to non-DM patients. In addition, DM patients possessed higher numbers of progressive segments per patient, ΔSIS and ΔSSS compared with non-DM individuals (P < 0.001, P = 0.029 and P < 0.001 respectively). A larger number of patients with at least two progressive lesions were found in the DM group (P = 0.006). Multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated that DM (OR: 4.81; 95% CI 1.64–14.07, P = 0.004) was independently associated with plaque progression.

Conclusions

DM is closely associated with the prevalence and severity of CCTA verified CAD progression. These findings suggest that physicians should pay attention to non-stent segments and the management of non-stent segment plaque progression, particularly to DM patients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Diabetes Mellitus (DM) is a chronic disease that endangers human health, causing a severe socioeconomic burden. The International Diabetes Federation’s global estimates suggest that ~ 422 million individuals suffer from DM worldwide, and this number is projected to increase to 642 million by 2040 [1]. Cardiovascular involvement increases the risk of adverse events in DM patients [2, 3]. Serial CCTAs demonstrated that DM patients have a larger numbers of atherosclerotic plaques compared to non-DM patients at an interval of median 3.2 years [4]. The role of DM in CAD progression is now universally accepted [5,6,7].

The susceptibility of DM patients to a severe plaques and PCI is well-known [8, 9]. DM patients are more likely to develop in-stent restenosis, leading to a poorer clinical outcomes and higher target lesion revascularization rates after PCI [10, 11]. The advent of drug eluting stents (DES) has decreased restenosis rates [12]. Poor outcomes in CAD patients not only originate from in-stent restenosis, but also non-treated segments [13]. The role of untreated and non-stenotic segments during CAD progression and their relationship to secondary adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) remain undefined.

Assessments of atheromatous plaque progression between elective PCI treated patients with or without DM are sparse. The aim of this study was to compare the prevalence and severity of plaque progression in stented subjects with and without diabetes and to compare the between-group differences in the characteristics and distribution of these progressive plaques through serial CCTAs.

Methods

Study population

From December 2015 to October 2018, 106 patients who underwent serial CCTA examinations in our hospital were consecutively included. Baseline CCTAs were performed for angina, suspected angina, abnormal ECGs, and the preoperative evaluation or screening of CAD in the population with multiple risk factors. Follow-up CCTA were performed for postoperative checks. Inclusion criteria were: (i) elective percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) performed in our hospital without prior known CAD; (ii) clinically indicated serial CCTAs arranged 1 month before and at least 6 months after PCI. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) repeated revascularization; and (ii) scans with significant artifacts or poor image quality. A total of 98 patients were finally included. Eight patients were excluded for poor image quality (n = 3) or shorter inter-scan periods (n = 5). All subjects were categorized into 2 groups according to DM history (DM and non-DM groups). DM was defined in accordance with the American Diabetes Association (ADA) diagnosis [14]. Clinical variables, CAD risk factors and statin use within the groups were obtained through patient questionnaires and medical records.

CCTA scanning protocols

CCTAs indications, data acquisition and image post-processing were performed in accordance with the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography guidelines [15]. CCTA was performed using a Siemens DSCT scanner (SOMATOM Definition, Siemens Medical Solutions, Forchheim, Germany). Beta blockers were not administered for heart rate reduction. The scanning scope was from the tracheal bifurcation to 20 mm below the inferior cardiac apex. A 70–90-mL (dependent on the body mass index) bolus of iodinated contrast agent (iopamidol, 370 mg of iodine/mL; BraccoSine Pharmaceutical Corp. Ltd, Shanghai, China) was injected into the antecubital vein at a flow rate of 5 mL/s. Next, a 20-mL saline chaser was injected at the same rate. Scan parameters were tube voltage 100–120 kV (adapted to body mass index); tube current, 220 mAs; collimation, 64 × 0.6 mm; rotation time, 0.33 s and pitch, 0.2–0.5 (adapted to the heart rate). Retrospective electrocardiographic gating was used to eliminate cardiac motion artefacts. Initial datasets were immediately reconstructed upon completion of the scan and images of optimal quality were transferred to a post-processing workstation (Syngo-Imaging, Siemens Medical Solution Systems, Forchheim, Germany) for image analysis. Sinogram Affirmed Iterative Reconstruction (SAFIRE) was used when plaques were highly calcified, to reduce image noise and optimize image quality. Coronary artery plaques were evaluated through maximum intensity projections, multiplanar reconstructions, curvature plane reconstructions and volume reconstructions.

Serial CCTAs analysis

For longitudinal comparisons of the CCTAs, segments and vessels were identified by landmarks including bifurcations carina and side branches at follow-up. Segments and vessels with stents on follow-up CCTA (CCTA2) images were excluded from the analyses. Finally, an equal number of segments and vessels were assessed at baseline and follow-up. For segment-wise analysis, coronary artery trees were divided into 16 separate segments based on a modified AHA classification (Fig. 1) [16]. The extent of stenosis in the individual segments was qualitatively analyzed and graded by two professional cardiologists who were masked to the clinical results and group identities, using a 5-point scale based on CAD-RADS [17]: Grade 0: absence of plaques; Grade 1-minimal (< 25% luminal stenosis); Grade 2-mild (25–50% luminal stenosis); Grade 3-moderate (50–70% luminal stenosis); Grade 4-severe (70–99% luminal stenosis); Grade 5-totally occluded. Any discrepancies in the interpretations of the two observers were resolved by consensus.

Schematic diagram of coronary artery plaque score in coronary artery tree model. In this example, plaques distribute on proximal right coronary artery, proximal left anterior descending and proximal left circumflex respectively. Segment stenosis score was calculated by summation of minimal plaque in the proximal right coronary artery (scored 1), severe plaque in the proximal left anterior descending artery (scored 4) and mild plaque (scored 2) in the proximal left circumflex. Thus, the segment stenosis score is 7 out of a possible 80. Segment involvement score was calculated by summation of the absolute number of coronary segments exhibiting plaque. The segment involvement score in this example is 3 out of a possible 16

Segment involvement scores (SIS) reflecting the extent of stenosis were calculated as the total number of coronary artery segments with plaques (minimum 0, maximum 16). Segment stenosis scores (SSS) reflecting the severity of stenosis were calculated as the summation of the extent scores of all 16 individual segments (scale: 0 to 80). These two variables were calculated based on the final results of the segmentation assessments of the two cardiologists. SSS (ΔSSS) and SIS changes (ΔSIS), as variables to evaluate the severity of atheromatous plaque progression, were defined as SSS and SIS at CCTA2 minus that of CCTA1. Plaques were visually classified as calcified when containing a calcified composition, or non-calcified plaques containing partial or no-calcification.

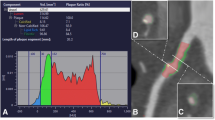

The prevalence of atheromatous plaque progression was assessed at per-patient, per-vessel, and per-segment levels. For patient analysis, CAD progression was defined as the increase in extent scores of any coronary segment in the coronary artery tree. For per-vessel analysis, non-stent vessels with progressive segments on CCTA2 were defined as progressive vessels. On the per-segment level, coronary plaque progression was defined as an increased extent score of individual segments. Figure 2 shows representative CCTA images for plaque progression. The severity of plaque progression was assessed mainly by ΔSSS, ΔSIS, and the number of progressive vessels and segments.

Representative serial CCTAs images. a A serial CCTAs of a non-diabetic patient. At the baseline CCTA (a1) (performed on April, 2014), no plaque was found on the proximal right coronary artery (pRCA). At the second CCTA (a2) (performed on July, 2018), a newly developed calcific plaque was noticed on the pRCA with minimal stenosis. b A serial CCTAs of a diabetic patient. At the baseline CCTA (b1) performed on February, 2013, a mixed plaque with mild stenosis was found on the proximal left anterior descending artery (pLAD). At the second CCTA (b2) performed on March, 2017, the mixed plaque on the pLAD has progressed into severe stenosis

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 25.0). Baseline clinical and imaging data were stratified based on DM status. Categorical variables were expressed as the number (%) and compared using Chi square test or fisher’s exact test (if the expected cell value was ≤ 5). Continuous variables were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation for normally distributed data or the Median (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed data. Normally distributed continuous variables such as age and BMI were compared using an unpaired Students t test. For non-normally distributed variables such as SSS, SIS, ΔSIS and ΔSSS, non-parametric tests were used. To compare baseline CTA data and the changes over time between the two groups, Mann–Whitney U tests were employed. The correlation between plaque progression and clinical variables were analyzed using logistic regression analysis. Variables with P-values ≤ 0.1 in univariate analysis and recognized cardiovascular risk factors were entered en-bloc into the multivariable model. Two-tailed P-values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Study population

A total of 256 non-stent vessels (DM vs non-DM: 88 vs 168) with 1355 non-stented segments (DM vs non-DM: 485 vs 870) in 98 stented patients (DM vs non-DM: 32 vs 36) were evaluated. The mean age of the participants was 69.9 ± 11.0 years, and 83.7% were male. The clinical characteristics of DM and non-DM patients are shown in Table 1. Higher BMIs were observed in DM individuals (P = 0.038), whilst no significant discrepancies regarding age, sex, high-risk factors and inter-scan periods between the two groups. Amongst the stents, there were no significant differences in distribution, burden, or stents involving segments and vessels between DM and non-DM groups (P > 0.05). The use of statins, clopidogrel/ticlopidine and other prescriptions at discharge did not significantly differ between the two study groups.

Prevalence and characteristics of progressive atheromatous plaques in DM and non-DM patients

The prevalence and characteristics of progressive atheromatous plaques are shown in Table 2. During the median 1.5 years follow-up, 26 (72.2%) DM patients and 25 (40.3%) non-DM patients developed progressive atheromatous plaques (P = 0.002). A larger number of atheromatous plaques progressions were observed in the non-stented vessels (55.7% vs 23.2%, P < 0.001) and non-stented segments (10.3% vs 4.4%, P < 0.001) of DM patients compared to non-DM patients.

The larger number of progressive lesions in DM patients distributed on the main left artery (LM) (24.2% vs 5.2%, P = 0.007) and right coronary artery (RCA) (50% vs 21.1%, P = 0.028) compared to non-DM patients. For segment-wise analysis, proximal left anterior descending (LADs) of DM patients were more prone to plaque progression than those of non-DM patients (33.3% vs 5.1%, P = 0.009). A larger number of calcified plaques and original non-stenotic segments with plaque progression were observed in DM compared to non-DM patients (P = 0.014 and P = 0.005, respectively).

Severity and extent of atheromatous plaque progression in DM and non-DM patients

Approximately 1.0 (interquartile range (IQR): 0–2.0) segment per DM patient and 0 (IQR: 0–1) segments per non-DM patient were found to possess plaques progression (P = 0.001). A larger number of DM patients had at least two progressive segments compared to non-DM patients (P = 0.006). No significant between-group differences were observed in patients with single progressive segments (P > 0.05). The number of progressive vessels between the two groups also did not differ (P > 0.05).

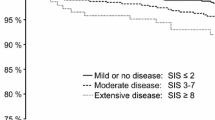

The segment stenosis score (SSS) relatively increased from 6 (IQR: 3.25–8) to 7.5 (IQR: 5.25–11.5) in DM patients, and from 4 (IQR: 2–10) to 5 (IQR: 2–10) in non-DM patients (P < 0.001 for between-group differences in change). SIS scores increased from 3 (IQR: 2–4) to 3 (IQR: 2–5) in DM patients and from 2 (IQR: 1–4) to 3 (IQR: 1–4) in non-DM patients (P = 0.029 for between-group differences in change, Fig. 3, Table 3).

Univariate and multivariate analysis

The results of univariate and multivariate regression analyses are shown in Table 4. In the univariate analysis, the inter-scan period, chest pain at baseline, cardiovascular disease (CVD) and DM were significantly associated with plaque progression. Multivariate regression analysis when adjusted for confounding factors demonstrated that DM (OR: 4.81; 95% CI 1.64–14.07, P = 0.004) and chest pain at baseline (OR: 3.55; 95% CI 1.22–10.32, P = 0.020) were independently associated with plaque progression.

Discussion

The main findings of this study were that (1) compared to non-DM patients, diabetic patients showed a higher prevalence and severity of plaque progression after stenting; (2) the larger number of progressive lesions observed in the DM group distributed on LM, RCA and proximal LAD, and were characterized by more frequent non-stenotic segments and non-calcified plaques compared to non-DM groups; (3) diabetes was an independent risk factor for plaque progression in stented patients after the adjustment for confounding factors.

Despite the different clinical features of CAD patients, all exhibited multiple concomitant metabolic abnormalities, in which synergy affected the progression of coronary heart disease, increasing the risk of adverse cardiovascular events [18]. Previous studies confirmed that obesity or Mets aggravate the plaque burden and worsen the prognosis of CAD patients [19]. Statins reduce the plaque/lipid composition, increase plaque stability, and improve adverse cardiovascular events through lowering circulating lipid levels. Studies have shown that during a relatively short follow-up (~ 1 year), moderate doses of statins do not significantly change the plaque phenotype and increase calcified plaque volumes [20,21,22]. A possible explanation for this is the limited time window to exert an effect.

In this study, although a small number of patients did not receive optimal statin use in accordance with treatment guidelines after discharge, no significant differences in statin usage between DM and non-DM groups were observed. In addition, DM patients are susceptible to a higher prevalence of CAD and plaque progression, even when receiving lipid-lowering therapy [23, 24]. This implies that DM may be an independent risk factor for plaque progression.

DM markedly impaired myocardial microvascular perfusion which is regarded a clinically significant predictive marker of plaque progression in CAD [25,26,27]. Previous studies evaluating the use of serial CCTAs, verified that higher levels of plaque progression occurred in DM patients [4, 5]. Similar results were obtained in this study, which included elective PCI treated patients. Insulin resistance causes early endothelial dysfunction by decreasing eNOS activity and nitric oxide production. Monocyte/macrophage activation leads to enhanced inflammation in DM patients, which impairs endothelial functions and limits repair of the endothelium [28, 29]. These effects enhanced the severity of pre-existing atheromatous plaques and increased the prevalence of newly developed plaques in non-stenotic segments. Thus, strict glycemic control and intensive DM management should be prioritized to prevent CAD progression and secondary adverse cardiovascular events in DM patients.

Previous studies investigated the distribution of atherosclerosis between DM and non-DM groups, suggesting that proximal segments, particularly proximal LAD were more susceptible to plaques in DM patients [30]. Our data indicated that more progressive lesions in stented patients with DM were located in LM, RCA and the proximal LAD compared to patients without DM. Possible explanations for these observations are wall shear stress (WSS) in different parts of the coronary artery tree. It is recognized that low WSS is independently associated with an increased plaque burden and adverse plaque characteristics at follow-up [31,32,33]. WSS at the proximal segments, such as LM and proximal LAD, may be lower than those distal to the vessel. RCA is more likely to possess a lower WSS due to its relatively larger diameter.

In addition to WSS and compared to non-DM patients, circulating tissue factor procoagulants make DM patients susceptible to hypercoagulation [34]. Plasma viscosity, as an additional determinant of endothelial function and the maintenance of normal vascular resistance, can affect atheromatous plaque progression when increased. Hypercoagulability decreased the WSS so that the coronary artery trees in DM patients were exposed to higher levels of plaque progression compared to non-DM patients. LM and proximal LAD are located at the ostial of the vessels and when significant obstruction occurs, an insufficient blood supply to the downstream vessels and more extensive myocardial damage results. Further studies are now required to establish the exact relationship between coronary arrangements and plaque progression.

An additional finding was that, compared to non-DM patients, non-calcified plaques in DM patients showed higher rates of plaque progression. The quantification of non-calcified plaques can improve the prognostic value of CCTA to predict future cardiovascular events and is regarded as an independent predictor of developing acute coronary syndrome (ACS) [35, 36]. As the progression of non-calcified plaques in DM patients are more common after stenting than non-DM patients, they may be more at risk to ACS. Regular re-examination and evaluation of the plaque changes in the non-stent segments of DM individuals should be given attention.

Baseline disease increased the risk of plaque progression [37, 38]. Based on our data, the same correlation did not exist between baseline SSS or SIS and plaque progression. This may due to the study population being comprised of CAD patients who required PCI based on clinical decision making, which differs to the general population. An interesting discovery was that chest symptoms at baseline CCTA could effectively predict plaque progression. Chest pain was closely related to coronary plaque burden and long-term poor prognosis, facilitating the risk stratification of patients combined with cardiovascular risk factors [39, 40]. To-date, discussions on whether baseline chest symptoms affect plaque progression and prognosis in stent implanted patients are limited. Due to the single-center and retrospective nature of this study, we were unable to draw definitive conclusions. Further prospective, multi-center studies are required to identify the impact of baseline chest symptoms on CAD progression and prognosis in PCI treated patients, and to evaluate whether patients with chest pain require more aggressive therapy.

The present study had some limitations. First, the results were based on a small sample size and the inclusion of a larger study sample would strengthen the statistical analyses. Secondly, the study was retrospective and single-centered, leading to potential selection bias. The results remain to be verified by prospective and multicenter studies. Thirdly, we did not systematically correlate our findings on CCTA with angiography for luminal stenosis assessments, as the high-diagnostic accuracy of CCTA for the assessment of coronary atherosclerosis (which is comparable to angiography) is widely accepted. Finally, we recorded baseline chest pain, which is a relatively subjective indicator. Two extremes require assessments based on chest symptoms alone, to minimize subjective errors.

Conclusions

DM patients have a higher prevalence and severity of plaque progression of non-stented segments after PCI. Compared to non-DM individuals, more progressive lesions were located in LM, proximal LAD and the non-stenotic segments of DM-patients, which were characterized as non-calcified plaques. These findings suggest that initially non-obstructive disease may over time progress to significant stenosis, resulting in non-target-lesion PCI, particularly in DM patients. Physicians therefore should pay attention to non-stent segments and the management of non-stent segment plaque progression.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DM:

-

diabetes mellitus

- CAD:

-

coronary artery disease

- CCTA:

-

coronary computed tomography angiography

- PCI:

-

percutaneous coronary intervention

- SIS:

-

segment involvement scores

- SSS:

-

segment stenosis scores

- DES:

-

drug eluting stents

- DES:

-

drug eluting stents

- ΔSSS:

-

segment stenosis score change

- MACE:

-

main adverse cardiovascular events

- LM:

-

left main

- RCA:

-

right coronary artery

- LAD:

-

left anterior descending

- LCx:

-

left circumflex

- CVD:

-

cardiovascular disease

- ACS:

-

acute coronary syndrome

References

Diabetes Atlas 8th Edition. International Diabetes Federation. http://www.diabetesatlas.org. Accessed 10 Sept 2018.

Sarwar N, Gao P, Seshasai SR, Gobin R, Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Ingelsson E, Lawlor DA, Selvin E, Stampfer M, et al. Diabetes mellitus, fasting blood glucose concentration, and risk of vascular disease: a collaborative meta-analysis of 102 prospective studies. Lancet. 2010;375(9733):2215–22.

Mohammedi K, Woodward M, Marre M, Colagiuri S, Cooper M, Harrap S, Mancia G, Poulter N, Williams B, Zoungas S, et al. Comparative effects of microvascular and macrovascular disease on the risk of major outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):95.

Won KB, Lee SE, Lee BK, Park HB, Heo R, Rizvi A, Lin FY, Kumar A, Hadamitzky M, Kim YJ, et al. Longitudinal assessment of coronary plaque volume change related to glycemic status using serial coronary computed tomography angiography: A PARADIGM (Progression of AtheRosclerotic PlAque DetermIned by Computed TomoGraphic Angiography Imaging) substudy. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2018;13(2):142–7.

Won KB, Han D, Lee JH, Lee SE, Sung JM, Choi SY, Chun EJ, Park SH, Han HW, Sung J, et al. Evaluation of the impact of glycemic status on the progression of coronary artery calcification in asymptomatic individuals. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):4.

Kowall B, Lehmann N, Moebus S, Erbel R, Jöckel KH, Stang A. Associations between HbA1c and progression of coronary artery calcification. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016;31:S104–5.

Wang H, Tang Z, Li X, Hu B, Feng B. Angiographic evaluation of the effects of glucose metabolic status on progression of coronary artery lesions in patients with coronary artery disease. J Diabetes. 2014;6(6):541–6.

Piccolo R, Giustino G, Mehran R, Windecker S. Stable coronary artery disease: revascularisation and invasive strategies. Lancet. 2015;386(9994):702–13.

Rana JS, Dunning A, Achenbach S, Al-Mallah M, Budoff MJ, Cademartiri F, Callister TQ, Chang HJ, Cheng VY, Chinnaiyan K, et al. Differences in prevalence, extent, severity, and prognosis of coronary artery disease among patients with and without diabetes undergoing coronary computed tomography angiography: results from 10,110 individuals from the CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes): an InteRnational Multicenter Registry. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(8):1787–94.

Antonsen L, Maeng M, Thayssen P, Christiansen EH, Hansen KN, Kaltoft A, Hansen HS, Thuesen L, Lassen JF, Jensen LO. Intimal hyperplasia and vascular remodeling after everolimus-eluting and sirolimus-eluting stent implantation in diabetic patients: the randomized Diabetes and Drug-Eluting Stent (DiabeDES) IV Intravascular Ultrasound trial. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2014;83(6):864–72.

Konigstein M, Ben-Yehuda O, Smits PC, Love MP, Banai S, Perlman GY, Golomb M, Ozan MO, Liu M, Leon MB, et al. Outcomes among diabetic patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with contemporary drug-eluting stents: analysis from the bionics randomized trial. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;11(24):2467–76.

Piccolo R, Bonaa KH, Efthimiou O, Varenne O, Baldo A, Urban P, Kaiser C, Remkes W, Raber L, de Belder A, et al. Drug-eluting or bare-metal stents for percutaneous coronary intervention: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2019;393(10190):2503–10.

Kennedy MW, Fabris E, Suryapranata H, Kedhi E. Is ischemia the only factor predicting cardiovascular outcomes in all diabetes mellitus patients? Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):51.

Association AD. Classification and diagnosis of diabetes: standards of medical care in diabetes—2018. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(Suppl 1):S13–s27.

Abbara S, Blanke P, Maroules CD, Cheezum M, Choi AD, Han BK, Marwan M, Naoum C, Norgaard BL, Rubinshtein R, et al. SCCT guidelines for the performance and acquisition of coronary computed tomographic angiography: a report of the society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography Guidelines Committee: Endorsed by the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI). J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10(6):435–49.

Austen WG, Edwards JE, Frye RL, Gensini GG, Gott VL, Griffith LS, McGoon DC, Murphy ML, Roe BB. A reporting system on patients evaluated for coronary artery disease. Report of the Ad Hoc Committee for Grading of Coronary Artery Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery. Am Heart Assoc Circ. 1975;51(4):5–40.

Cury RC, Abbara S, Achenbach S, Agatston A, Berman DS, Budoff MJ, Dill KE, Jacobs JE, Maroules CD, Rubin GD, et al. CAD-RADS(TM) Coronary Artery Disease—Reporting and Data System An expert consensus document of the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography (SCCT), the American College of Radiology (ACR) and the North American Society for Cardiovascular Imaging (NASCI) Endorsed by the American College of Cardiology. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2016;10(4):269–81.

Deseive S, Straub R, Kupke M, Broersen A, Kitslaar PH, Stocker TJ, Massberg S, Hadamitzky M, Hausleiter J. Impact of diabetes on coronary artery plaque volume by coronary CT angiography and subsequent adverse cardiac events. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2019;13(1):31–7.

Hulten EA, Bittencourt MS, Preston R, Singh A, Romagnolli C, Ghoshhajra B, Shah R, Abbasi S, Abbara S, Nasir K, et al. Obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular prognosis: from the Partners coronary computed tomography angiography registry. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):14.

Raber L, Taniwaki M, Zaugg S, Kelbaek H, Roffi M, Holmvang L, Noble S, Pedrazzini G, Moschovitis A, Luscher TF, et al. Effect of high-intensity statin therapy on atherosclerosis in non-infarct-related coronary arteries (IBIS-4): a serial intravascular ultrasonography study. Eur Heart J. 2015;36(8):490–500.

Raber L, Koskinas KC, Yamaji K, Taniwaki M, Roffi M, Holmvang L, Garcia Garcia HM, Zanchin T, Maldonado R, Moschovitis A, et al. Changes in coronary plaque composition in patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with high-intensity statin therapy (IBIS-4): a serial optical coherence tomography study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;12(8 Pt 1):1518–28.

Andelius L, Mortensen MB, Norgaard BL, Abdulla J. Impact of statin therapy on coronary plaque burden and composition assessed by coronary computed tomographic angiography: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;19(8):850–8.

Kovarnik T, Chen Z, Mintz GS, Wahle A, Bayerova K, Kral A, Chval M, Kopriva K, Lopez J, Sonka M, et al. Plaque volume and plaque risk profile in diabetic vs. non-diabetic patients undergoing lipid-lowering therapy: a study based on 3D intravascular ultrasound and virtual histology. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):156.

Venuraju SM, Lahiri A. Duration of type 2 diabetes mellitus and systolic blood pressure as determinants of severity of coronary stenosis and adverse events in an asymptomatic diabetic population: PROCEED study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2019;18(1):51.

Berry C, Noble S, Gregoire JC, Ibrahim R, Levesquie S, Lavoie MA, L’Allier PL, Tardif JC. Glycaemic status influences the nature and severity of coronary artery disease. Diabetologia. 2010;53(4):652–8.

Liu X, Yang ZG, Gao Y, Xie LJ, Jiang L, Hu BY, Diao KY, Shi K, Xu HY, Shen MT, et al. Left ventricular subclinical myocardial dysfunction in uncomplicated type 2 diabetes mellitus is associated with impaired myocardial perfusion: a contrast-enhanced cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2018;17(1):139.

Gao Y, Yang ZG, Ren Y, Liu X, Jiang L, Xie LJ, Hu BY, Shen MT, Xu HY, Li ZL, et al. Evaluation myocardial fibrosis in diabetes with cardiac magnetic resonance T1-mapping: correlation with the high-level hemoglobin A1c. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2019;150:72–80.

Kuschnerus K, Landmesser U, Krankel N. Vascular repair strategies in type 2 diabetes: novel insights. Cardiovasc Diagnosis Ther. 2015;5(5):374–86.

Jansen F, Yang X, Hoelscher M, Cattelan A, Schmitz T, Proebsting S, Wenzel D, Vosen S, Franklin BS, Fleischmann BK, et al. Endothelial microparticle-mediated transfer of MicroRNA-126 promotes vascular endothelial cell repair via SPRED1 and is abrogated in glucose-damaged endothelial microparticles. Circulation. 2013;128(18):2026–38.

Chu ZG, Yang ZG, Dong ZH, Zhu ZY, Peng LQ, Shao H, He C, Deng W, Tang SS, Chen J. Characteristics of coronary artery disease in symptomatic type 2 diabetic patients: evaluation with CT angiography. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2010;9:74.

Samady H, Eshtehardi P, McDaniel MC, Suo J, Dhawan SS, Maynard C, Timmins LH, Quyyumi AA, Giddens DP. Coronary artery wall shear stress is associated with progression and transformation of atherosclerotic plaque and arterial remodeling in patients with coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2011;124(7):779–88.

Park JB, Choi G, Chun EJ, Kim HJ, Park J, Jung JH, Lee MH, Otake H, Doh JH, Nam CW, et al. Computational fluid dynamic measures of wall shear stress are related to coronary lesion characteristics. Heart. 2016;102(20):1655–61.

Stone PH, Saito S, Takahashi S, Makita Y, Nakamura S, Kawasaki T, Takahashi A, Katsuki T, Nakamura S, Namiki A, et al. Prediction of progression of coronary artery disease and clinical outcomes using vascular profiling of endothelial shear stress and arterial plaque characteristics: the PREDICTION Study. Circulation. 2012;126(2):172–81.

Low Wang CC, Hess CN, Hiatt WR, Goldfine AB. Clinical update: cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and heart failure in type 2 diabetes mellitus—mechanisms, management, and clinical considerations. Circulation. 2016;133(24):2459–502.

Maurovich-Horvat P, Ferencik M, Voros S, Merkely B, Hoffmann U. Comprehensive plaque assessment by coronary CT angiography. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2014;11(7):390–402.

Versteylen MO, Kietselaer BL, Dagnelie PC, Joosen IA, Dedic A, Raaijmakers RH, Wildberger JE, Nieman K, Crijns HJ, Niessen WJ, et al. Additive value of semiautomated quantification of coronary artery disease using cardiac computed tomographic angiography to predict future acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(22):2296–305.

Anand DV, Lim E, Darko D, Bassett P, Hopkins D, Lipkin D, Corder R, Lahiri A. Determinants of progression of coronary artery calcification in type 2 diabetes role of glycemic control and inflammatory/vascular calcification markers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(23):2218–25.

Yang J, Dou G, Tesche C, De Cecco CN, Jacobs BE, Schoepf UJ, Chen Y. Progression of coronary atherosclerotic plaque burden and relationship with adverse cardiovascular event in asymptomatic diabetic patients. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2019;19(1):39.

Fujimoto S, Kondo T, Kodama T, Orihara T, Sugiyama J, Kondo M, Endo A, Fukazawa H, Nagaoka H, Oida A, et al. Coronary computed tomography angiography-based coronary risk stratification in subjects presenting with no or atypical symptoms. Circ J. 2012;76(10):2419–25.

The SC. CT coronary angiography in patients with suspected angina due to coronary heart disease (SCOT-HEART): an open-label, parallel-group, multicentre trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9985):2383–91.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81471721, 81471722,81641169, 81771887 and 81771897), 1·3·5 project for disciplines of excellence, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2016YFC1300300), Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University (No: NCET-13-0386) and Program for Young Scholars and Innovative Research Team in Sichuan Province of China (2017TD0005).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SR and SK designed the study. SR researched data, and wrote the manuscript. SK contributed to the discussion,analyzed the data, drafted the manuscript and editing and review of the manuscript. YZG supervised the overall study and contributed to study design, editing and review of the manuscript. GYK and DKY researched data and review the manuscript. GY, ZY and HS was responsible for collecting, sorting and statistical data. YZG and GYK are the guarantor of this work and, as such, had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of West China Hospital, Sichuan University (Chengdu, Sichuan, China) with a waiver of informed consent due to the retrospective nature of this investigation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shi, R., Shi, K., Yang, Zg. et al. Serial coronary computed tomography angiography-verified coronary plaque progression: comparison of stented patients with or without diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 18, 123 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-019-0924-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-019-0924-z