Abstract

Background

Advanced glycation end-products play a role in diabetic vascular complications. Their optical properties allow to estimate their accumulation in tissues by measuring the skin autofluorescence (SAF). We searched for an association between SAF and major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) incidence in subjects with Type 1 Diabetes (T1D) during a 7 year follow-up.

Methods

During year 2009, 232 subjects with T1D were included. SAF measurement, clinical [age, sex, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities] and biological data (HbA1C, blood lipids, renal parameters) were recorded. MACE (myocardial infarction, stroke, lower extremity amputation or a revascularization procedure) were registered at visits in the center or by phone call to general practitioners until 2016.

Results

The participants were mainly men (59.5%), 51.5 ± 16.7 years old, with BMI 25.0 ± 4.1 kg/m2, diabetes duration 21.5 ± 13.6 years, HbA1C 7.6 ± 1.1%. LDL cholesterol was 1.04 ± 0.29 g/L, estimated Glomerular Filtration Rates (CKD-EPI): 86.3 ± 26.6 ml/min/1.73 m2. Among these subjects, 25.1% were smokers, 45.3% had arterial hypertension, 15.9% had elevated AER (≥ 30 mg/24 h), and 9.9% subjects had a history of previous MACE. From 2009 to 2016, 22 patients had at least one new MACE: 6 myocardial infarctions, 1 lower limb amputation, 15 revascularization procedures. Their SAF was 2.63 ± 0.73 arbitrary units (AU) vs 2.08 ± 0.54 for other patients (p = 0.002). Using Cox-model, after adjustment for age (as the scale time), sex, diabetes duration, BMI, hypertension, smoking status, albumin excretion rates, statin treatment and a previous history of MACE, higher baseline levels of SAF were significantly associated with an increased risk of MACE during follow-up (HR = 4.13 [1.30–13.07]; p = 0.02 for 1 AU of SAF) and Kaplan–Meier curve follow-up showed significantly more frequent MACE in group with SAF upper the median (p = 0.001).

Conclusion

A high SAF predicts MACE in patients with T1D.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the decline of cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes (T1D) [1], it remains by far the first cause of mortality, as recently reported in patients with long duration of diabetes [2], and a major concern even in children who often present features of subclinical cardiovascular disease [3]. The cardiovascular risk of subjects with T1D is influenced by modifiable conventional risk factors such as arterial hypertension, dyslipidemia, and smoking, [4], and is strongly higher in the presence of diabetic nephropathy [5], but hyperglycaemia by itself is thought to play an important role.

Long-term hyperglycaemia promotes cardiovascular mortality, with a gradual increase of hazard ratios for death among patients with T1D compared to non diabetic subjects according to the HbA1C levels [6]. However a risk persists for well-controlled subjects with HbA1C ≤ 6.9%. The effect of intensive glucose control on cardiovascular events was significant only 11 years after the intensive glucose control intervention in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial, owing to a “glucose memory” effect [7]. A recent detailed analysis of cardiovascular risk factors of the DCCT-EDIC participants emphasized the importance of the mean time-weighted HbA1C [8].

Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) generated from excess glucose have deleterious effects on endothelial cells [9]. They are thought to contribute to the memory of hyperglycaemia [10]. The skin concentrations of AGEs have been related to the progression of intima-media thickness in the DCCT-EDIC study [11]. Due to their fluorescent properties, the accumulation of AGEs in tissues can be simply estimated by measuring the skin autofluorescence (SAF) [12]. SAF predicted later cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes [13]. We have related it to later impaired renal function [14] and neuropathy [15] in patients with T1D. However, the relation between SAF and later cardiovascular events has not been reported yet in T1D. We aimed to test the association between SAF and future occurrence of major adverse cardiovascular event (MACE) in patients with T1D followed-up over 7 years.

Subjects and methods

Design and patients

Two hundred and thirty-two patients with T1D were included consecutively in 2009 after consent during annual visit in University Hospital of Bordeaux. The only exclusion criterion was ultraviolet reflectance < 10% that precluded the measurement of SAF. The patients with skin phototypes V and VI were therefore not included. The following data were recorded at inclusion on the day of SAF measurement: age, sex, body mass index, duration of diabetes, treatment by Continuous Subcutaneous Insulin Infusion, arterial hypertension (blood pressure ≥ 140/90 mmHg and/or treatment with antihypertensive drug), treatment by statins, previous macrovascular events, and smoking history. The biological data recorded included HbA1c levels, blood lipids, the Albumin Excretion Rates (AER), and serum creatinine to estimate the Glomerular Filtration Rates calculated with the CKD-EPI formula [16]. Participants were prospectively followed-up until the occurrence of new cases of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) till March 2017. Number of patients was mentioned when data were missing.

Skin autofluorescence (SAF)

The accumulation of AGEs was evaluated at inclusion [12], using the AGE-Reader (diagnOptics BV, Groningen, The Netherlands). The device illuminated 1 cm2 of the forearm skin. SAF values were calculated by dividing the mean emitted light intensity (excitation light source ranging from 300 to 420 nm) by the mean reflected excitation light intensity from the skin (over 300–420 nm). The patients with Fitzpatrick phototypes V and VI were not included due to their skin pigmentation, which had ultraviolet reflectance of < 10%. The results were the mean of three consecutive measurements of SAF and were expressed in arbitrary units (AU).

Outcomes

MACE were defined as myocardial infarction, stroke, lower limb amputation, or a revascularization procedure for coronary, carotid or lower limb arteries. Every year, patients came in visit at hospital, MACE was collected by physician if occurred since previous visit and recorded in the informatic medical folder of each patient. If we had no recent news we called practitioner to ask if MACE or death occurred.

Statistical methods

The results are presented as mean ± SD for continuous variables, or median (IQR) for those with skewed distribution. Categorial variables are presented as numbers (percentages). A Cox model with delayed entry (taking age as the scale-time) was used to investigate the association between SAF and MACE. R2 of the model has been calculated by the following formula: R2 = 1 − e − (LRT/n), where LRT is the likelihood-ratio statistic. Log-linearity of the model has been tested using SAF as a continuous variable and in quartile. Risk proportionality has been verified both by testing the interaction between SAF and time and by using Schoenfeld residuals. In a first step, analyses were performed to test the association between each co-variable and MACE in order to select variables for the multivariate analysis. Then, all the variables associated with MACE with a p value ≤ 0.10 were retained in the multivariate Cox model. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC) and results were considered significant when p < 0.05. Follow-up was analysed using Kaplan–Meier curve.

Results

Characteristics of the population at inclusion

Participants were mainly men (59.5%), 51.5 ± 16.7 years old, with a 21.5 ± 13.6 years diabetes duration. Their BMI was 25.0 ± 4.1 kg/m2, HbA1c 7.6 ± 1.1%, eGFR was 86.0 ± 26.3 ml/min/1.73 m2. Among them, 25.1% were smokers, 45.3% had arterial hypertension, 15.9% had elevated AER (≥ 30 mg/24H), and 9.9% had a history of previous macrovascular event. Their SAF was 2.13 ± 0.58 AU. The scatterplot for SAF over age is presented as a Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Subjects with new major adverse cardiovascular events during the follow-up

Twenty-two patients presented MACE during a median (IQR) duration of follow-up of 7.8 [7.6–8.0] years: 6 myocardial infarctions, 1 gangrene and 15 revascularization procedures. As compared to subjects without MACE, they were significantly more men, 10 years older, with 9 more years of diabetes duration, but similar HbA1c (Table 1). The lipid profiles did not significantly differ, but subjects with MACE were more likely to be treated by statins in comparison with subjects without MACE. Arterial hypertension, abnormal eGFR (< 60 ml/min/1.73 m2) and abnormal (> 30 mg/24 h) AER were significantly more frequent.

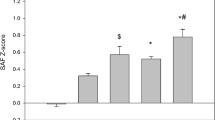

SAF and new major adverse cardiovascular events (Table 2, Fig. 1)

At inclusion, the SAF was 2.63 ± 0.73 AU in patients who presented MACE during the follow-up, vs 2.08 ± 0.54 for the others (p = 0.002). In addition to SAF, gender, duration of diabetes, BMI, hypertension, use of statins, smoking, renal parameters, and previous MACE were associated with MACE during the follow-up at a p value ≤ 0.10 and were retained in the multivariate analysis. SAF high level in 2009 was associated with significant increased risk of MACE during the 7 next years: HR = 4.13 [1.30;13.07] for increasing of +1 SAF AU (p = 0.02). Elevated hazard ratio for sex, MACE at baseline, BMI, statins treatment, abnormal eGFR, albumin excretion rates, hypertension and diabetes duration were not significantly associated with MACE. Using Kaplan–Meier curve, the follow-up of patients categorized in two groups according to SAF median (< 2.0 vs ≥ 2.0) showed that patients with high SAF more frequently developed MACE than those with SAF lower than median (p = 0.001). R2 of the model was estimated at 19%.

Discussion

Higher SAF measured in 2009 was associated with increased risk of later cardiovascular events (HR: 4.13, CI 95%: 1.30–13.07) after adjusting for diabetes duration, arterial hypertension, treatment by statins, renal parameters and previous cardiovascular events. SAF therefore appears as a significant predictor of cardiovascular events in Type 1 Diabetes. Participants with DT1 who experienced a cardiovascular event during the 7 years follow-up were older, with a 9 years longer diabetes duration, but similar HbA1C as compared to the others. They had more arterial hypertension, more dyslipidemia according to similar blood lipids despite twice more treated by statins, more frequent abnormal albumin excretion and estimated glomerular filtration rates, and more previous cardiovascular events. Their SAF were + 30% higher.

SAF to predict MACE

The prediction of cardiovascular events by SAF has already been reported in other diseases, as HIV infection [16] and Chronic Kidney Diseases although significance was lost (p = 0.09) after multivariate adjustments [17]. In type 2 diabetes, Lutgers et al. have shown that a high SAF (upper than median) was related to the 3 years cardiovascular prognosis, adjusted to the UKPDS risk score [13]. For Type 1 Diabetes, cross-sectional studies have reported relationship between SAF or skin intrinsic fluorescence and coronary calcifications [18], and clinical history of coronary heart disease [19]. But no prospective study had shown that SAF could predict cardiovascular events. In our previous analysis on the same cohort with a shorter follow-up of only 4 years [14], SAF predicted later eGFR impairement and later MACE: OR 4.84 (1.31–17.89), but the relation with later MACE did not reach significance with adjustment for previous MACE: OR 2.98 (0.77–11.47). However, this previous analysis was based on lower cases of cardio-vascular events. Three years later, the relation between SAF keeps significant after this adjustment: OR 4.13 (1.30–13.07). The longer follow-up with higher numbers of events now allows to reach significance for the prediction of macrovascular events in our patients independently from classical risk factors.

The role of AGEs

The main mechanism underlying this prediction is the deleterious effect of AGEs on the vascular system [9]. Previous studies found that serum levels of advanced glycation end-products-modified LDL [20], and Methylglyoxal [21] were related to later cardiovascular events or to the progression of atherosclerosis as reflected by the carotid intima-media thickness, in type 1 diabetes. AGEs are generated inside peripheral cells before they are liberated in the extracellular space [9]. Their accumulation in tissues as estimated by SAF is expected to better reflect their influence, than their circulating levels. SAF has been related to cardiac tissue glycation [22], inappropriate left ventricular mass and diastolic dysfunction [23], long wavelenght-1 and sublinical markers as the intima-media thickness [24] and it is increased in patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm [25]. The skin concentrations of AGEs have been related to coronary calcifications, left ventricular masses and progression of intima-media thickness in the DCCT-EDIC study [11]. SAF was related to the age of the participants (ß = + 0.397; p < 0.001) which is very similar to reports from other groups in participants with T1D [26,27,28]. Although an indirect estimation of the accumulation of AGEs, SAF has some advantages on skin biopsies: low cost, simplicity, non-invasiveness, and repeatability.

SAF and metabolic memory

The SAF may predict macrovascular events because it is a marker of the metabolic memory of hyperglycaemia, which seems critical for macroangiopathy in T1D. The cardiovascular benefits of the intensive glucose control during the DCCT came apparent only later, 11 years after the end of its active phase [7], which led to propose the concept of glucose memory. This concept is also supported by the long-term results of the UKPDS for type 2 diabetes. A recent analysis of the risk factors for cardiovascular disease in the DCCT-EDIC participants has emphasized the major role of their mean time-weighted HbA1C, second only to age [8]. Previous studies have reported that SAF relates to the HbA1C of the previous years, better than to the present HbA1C in T1D [27, 29,30,31]. In elderly participants of the 3-City cohort study from the general population, we have shown that SAF relates to glycaemia and HbA1C measured ten years before, rather than to their values measured at the same time as SAF [32]. Most of the associations between skin intrinsic fluorescence and T1D complications lost significance after adjustment to the mean HbA1C over time for the DCCT participants [33]. The association between skin fluorescence and coronary arterial calcifications was however still significant after this adjustment, arguing for an additional value of the fluorescence measurement. But no prospective study had shown that SAF could predict cardiovascular events. In our previous analysis on the same cohort with a shorter follow-up of only 4 years [14], SAF predicted later eGFR impairement and later MACE: OR 4.84 (1.31–17.89), but the relation with later MACE did not reach significance with adjustment for previous MACE: OR 2.98 (0.77–11.47). Three years later, the relation between SAF keeps significant after this adjustment: OR 4.13 (1.30–13.07). In the real life, the history of HbA1C is often not complete for many T1D patients, and death from cardiovascular causes are thrice more frequent even for the best controlled (HbA1C ≤ 6.9%) according to the Swedish register [6]. This underlines the interest of a metabolic memory marker that predicts cardiac events.

Others factors

Hyperglycaemia-related mechanisms may not be the only explanation for the relationship between SAF and macrovascular diseases. SAF increases with age, the strongest risk factor for cardiovascular events in T1D [8]. SAF has recently been related to the components of the metabolic syndrome [34], especially low HDL-cholesterol and arterial hypertension [35], that increasingly mediate the effect of glucose control on cardiovascular risk in aging T1D [5]. The progression of SAF in our patients with T1D highly depends on their glomerular filtration rates [15], as expected because renal insufficiency reduces the clearance of AGEs. This effect probably worsens as SAF predicts the impairment of GFR in T1D [14]. Diabetic nephropathy is a well-known, major contributor to cardiovascular disease in T1D [36]. But the relation between SAF and cardiovascular events reported in our study, was still significant after adjusting for age, arterial hypertension, blood lipids and renal parameters.

Limitations

Some other hypothesis can however not be excluded on the basis of our study, which can be considered as limitations. We have recently shown that SAF quickly rises during acute renal failure [37]. That is a powerful predictor of major cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes [38], but to our knowledge this has not been reported for T1D. We also found that SAF progressed less in our patients whose T1D was treated by continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion CSII [15], which has been related to less cardiovascular mortality [39]. This suggests that glycaemic variability may play a role in the accumulation of AGEs: even transient pikes of hyperglycaemia may have deleterious effects on vascular cells [10]. Long-term glycemic variability has been related to a twice-higher risk of cardiovascular events in T1D [40]. Skin autofluorescence is however not influenced by short-term glycemic variations [41]. Finally, some reports have related SAF to physical activity indexes: aerobic exercise capacity, muscle strength [42], and regular performance of physical activities [43, 44], which has been related to less cardiovascular events in the FinnDiane cohort [45]. Some practical limitations must also be mentioned. According to French law, we did not categorize the participants according to their ethnicity, but some subjects were excluded due to their skin pigmentation as already mentioned. The measurement of SAF were performed on intact skin, but we can not rule out that some subjects might have applied some body lotions locally. Draelos et al. applied a topical AGE inhibitor (blueberry extract) on the skin of 20 women with diabetes during three months, and they did not report any change of their SAF on this time interval [46]. An important proportion of the variability of SAF is not explained by age and usual covariates, some studies have suggested that genetic [47] or dietary factors may play a role, as diet is a source of AGEs [48]. Smoking has been related to SAF [35] and the relation between SAF and MACE was adjusted for tobacco use in our study, but we did not collect detailed dietary informations, so we can not exclude the role of some specific diet components, like coffee [35].

Conclusion

SAF seems to be a good mean to predict MACE in T1D. Further works are now required to explore these hypothesis with more long term follow-up because fortunately only a few MACE occurred, a multicentric study with more patients is required to find strategies to slower the progression of SAF in T1D.

Abbreviations

- AER:

-

albumin excretion rate

- AGE:

-

advanced glycation end-products

- AU:

-

arbitrary unit

- BMI :

-

body mass index

- CSII:

-

continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion

- DCCT:

-

diabetes control and complications trial

- eGFR:

-

estimated glomerular filtration rates

- HbA1c:

-

glycated haemoglobin

- HIV:

-

human immunodeficiency virus

- HR:

-

hazard ratio

- IQR:

-

interquartile range

- MACE :

-

major adverse cardiovascular event

- SAF:

-

skin autofluorescence

- SD:

-

standard deviation

- T1D:

-

type 1 diabetes

- UKPDS:

-

United Kindom Prospective Diabetes Study

References

Rawshani A, Rawshani A, Franzen S, Eliasson B, Svensson AM, Miftaraj M, et al. Mortality and cardiovascular disease in type 1 and type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1407–18.

Tinsley LJ, Kupelian V, D’Eon SA, Pober D, Sun JK, King GL, et al. Association of glycemic control with reduced risk for large-vessel disease after more than 50 years of type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(10):3704–11.

Gourgari E, Dabelea D, Rother K. Modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease in children with type 1 diabetes: can early intervention prevent future cardiovascular events? Curr Diab Rep. 2017;17(12):134.

de Ferranti SD, de Boer IH, Fonseca V, Fox CS, Golden SH, Lavie CJ, et al. Type 1 diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association and American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(10):2843–63.

Tuomilehto J, Borch-Johnsen K, Molarius A, Forsen T, Rastenyte D, Sarti C, et al. Incidence of cardiovascular disease in Type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic subjects with and without diabetic nephropathy in Finland. Diabetologia. 1998;41(7):784–90.

Lind M, Svensson AM, Kosiborod M, Gudbjornsdottir S, Pivodic A, Wedel H, et al. Glycemic control and excess mortality in type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(21):1972–82.

Nathan DM, Cleary PA, Backlund JY, Genuth SM, Lachin JM, Orchard TJ, et al. Intensive diabetes treatment and cardiovascular disease in patients with type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(25):2643–53.

Diabetes C, Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes I, Complications Research G. Risk factors for cardiovascular disease in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2016;65(5):1370–9.

Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;414(6865):813–20.

El-Osta A, Brasacchio D, Yao D, Pocai A, Jones PL, Roeder RG, et al. Transient high glucose causes persistent epigenetic changes and altered gene expression during subsequent normoglycemia. J Exp Med. 2008;205(10):2409–17.

Monnier VM, Sun W, Gao X, Sell DR, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, et al. Skin collagen advanced glycation endproducts (AGEs) and the long-term progression of sub-clinical cardiovascular disease in type 1 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2015;14:118.

Meerwaldt R, Graaff R, Oomen PHN, Links TP, Jager JJ, Alderson NL, et al. Simple non-invasive assessment of advanced glycation endproduct accumulation. Diabetologia. 2004;47(7):1324–30.

Lutgers HL, Gerrits EG, Graaff R, Links TP, Sluiter WJ, Gans RO, et al. Skin autofluorescence provides additional information to the UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS) risk score for the estimation of cardiovascular prognosis in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2009;52(5):789–97.

Velayoudom-Cephise FL, Rajaobelina K, Helmer C, Nov S, Pupier E, Blanco L, et al. Skin autofluorescence predicts cardio-renal outcome in type 1 diabetes: a longitudinal study. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15(1):127.

Rajaobelina K, Farges B, Nov S, Maury E, Cephise-Velayoudom FL, Gin H, et al. Skin autofluorescence and peripheral neuropathy four years later in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33(2):e2832.

Sprenger HG, Bierman WF, Martes MI, Graaff R, van der Werf TS, Smit AJ. Skin advanced glycation end products in HIV infection are increased and predictive of development of cardiovascular events. AIDS. 2017;31(2):241–6.

Fraser SD, Roderick PJ, McIntyre NJ, Harris S, McIntyre CW, Fluck RJ, et al. Skin autofluorescence and all-cause mortality in stage 3 CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(8):1361–8.

Conway B, Edmundowicz D, Matter N, Maynard J, Orchard T. Skin fluorescence correlates strongly with coronary artery calcification severity in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12(5):339–45.

Conway BN, Aroda VR, Maynard JD, Matter N, Fernandez S, Ratner RE, et al. Skin intrinsic fluorescence is associated with coronary artery disease in individuals with long duration of type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(11):2331–6.

Lopes-Virella MF, Hunt KJ, Baker NL, Lachin J, Nathan DM, Virella G, et al. Levels of oxidized LDL and advanced glycation end products-modified LDL in circulating immune complexes are strongly associated with increased levels of carotid intima-media thickness and its progression in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes. 2011;60(2):582–9.

Hanssen NMJ, Scheijen J, Jorsal A, Parving HH, Tarnow L, Rossing P, et al. Higher plasma methylglyoxal levels are associated with incident cardiovascular disease in individuals with type 1 diabetes: a 12-year follow-up study. Diabetes. 2017;66(8):2278–83.

Hofmann B, Jacobs K, Navarrete Santos A, Wienke A, Silber RE, Simm A. Relationship between cardiac tissue glycation and skin autofluorescence in patients with coronary artery disease. Diabetes Metab. 2015;41(5):410–5.

Wang CC, Wang YC, Wang GJ, Shen MY, Chang YL, Liou SY, et al. Skin autofluorescence is associated with inappropriate left ventricular mass and diastolic dysfunction in subjects at risk for cardiovascular disease. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2017;16(1):15.

Sell DR, Sun W, Gao X, Strauch C, Lachin JM, Cleary PA, et al. Skin collagen fluorophore LW-1 versus skin fluorescence as markers for the long-term progression of subclinical macrovascular disease in type 1 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2016;15:30.

Boersema J, de Vos LC, Links TP, Mulder DJ, Smit AJ, Zeebregts CJ, et al. Skin accumulation of advanced glycation end products is increased in patients with an abdominal aortic aneurysm. J Vasc Surg. 2017;66(6):1696–703.

Cho YH, Craig ME, Januszewski AS, Benitez-Aguirre P, Hing S, Jenkins AJ, et al. Higher skin autofluorescence in young people with Type 1 diabetes and microvascular complications. Diabet Med. 2017;34(4):543–50.

Sugisawa E, Miura J, Iwamoto Y, Uchigata Y. Skin autofluorescence reflects integration of past long-term glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(8):2339–45.

Duda-Sobczak A, Falkowski B, Araszkiewicz A, Zozulinska-Ziolkiewicz D. Association between self-reported physical activity and skin autofluorescence, a marker of tissue accumulation of advanced glycation end products in adults with type 1 diabetes: a cross-sectional study. Clin Ther. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2018.02.016.

Genevieve M, Vivot A, Gonzalez C, Raffaitin C, Barberger-Gateau P, Gin H, et al. Skin autofluorescence is associated with past glycaemic control and complications in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(4):349–54.

Araszkiewicz A, Naskret D, Zozulinska-Ziolkiewicz D, Pilacinski S, Uruska A, Grzelka A, et al. Skin autofluorescence is associated with carotid intima-media thickness, diabetic microangiopathy, and long-lasting metabolic control in type 1 diabetic patients. Results from Poznan Prospective Study. Microvasc Res. 2015;98:62–7.

Banser A, Naafs JC, Hoorweg-Nijman JJ, van de Garde EM, van der Vorst MM. Advanced glycation end products, measured in skin, vs. HbA1c in children with type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pediatr Diabetes. 2016;17(6):426–32.

Rajaobelina K, Cougnard-Gregoire A, Delcourt C, Gin H, Barberger-Gateau P, Rigalleau V. Autofluorescence of skin advanced glycation end products: marker of metabolic memory in elderly population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2015;70(7):841–6.

Orchard TJ, Lyons TJ, Cleary PA, Braffett BH, Maynard J, Cowie C, et al. The association of skin intrinsic fluorescence with type 1 diabetes complications in the DCCT/EDIC study. Diabetes Care. 2013;36(10):3146–53.

van Waateringe RP, Slagter SN, van Beek AP, van der Klauw MM, van Vliet-Ostaptchouk JV, Graaff R, et al. Skin autofluorescence, a non-invasive biomarker for advanced glycation end products, is associated with the metabolic syndrome and its individual components. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2017;9:42.

Botros N, Sluik D, van Waateringe RP, de Vries JHM, Geelen A, Feskens EJM. Advanced glycation end-products (AGEs) and associations with cardio-metabolic, lifestyle, and dietary factors in a general population: the NQplus study. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33(5):e2892.

Jensen T, Borch-Johnsen K, Kofoed-Enevoldsen A, Deckert T. Coronary heart disease in young type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetic patients with and without diabetic nephropathy: incidence and risk factors. Diabetologia. 1987;30(3):144–8.

Lavielle A, Rubin S, Boyer A, Moreau K, Rajaobelina K, Combe C, et al. Skin autofluorescence in acute kidney injury. Crit Care. 2017;21(1):24.

Monseu M, Gand E, Saulnier PJ, Ragot S, Piguel X, Zaoui P, et al. Acute kidney injury predicts major adverse outcomes in diabetes: synergic impact with low glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(12):2333–40.

Steineck I, Cederholm J, Eliasson B, Rawshani A, Eeg-Olofsson K, Svensson AM, et al. Insulin pump therapy, multiple daily injections, and cardiovascular mortality in 18,168 people with type 1 diabetes: observational study. BMJ. 2015;350:h3234.

Gorst C, Kwok CS, Aslam S, Buchan I, Kontopantelis E, Myint PK, et al. Long-term glycemic variability and risk of adverse outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(12):2354–69.

Noordzij MJ, Lefrandt JD, Graaff R, Smit AJ. Skin autofluorescence and glycemic variability. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2010;12(7):581–5.

Momma H, Niu K, Kobayashi Y, Guan L, Sato M, Guo H, et al. Skin advanced glycation end product accumulation and muscle strength among adult men. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2011;111(7):1545–52.

Simon Klenovics K, Kollarova R, Hodosy J, Celec P, Sebekova K. Reference values of skin autofluorescence as an estimation of tissue accumulation of advanced glycation end products in a general Slovak population. Diabet Med. 2014;31(5):581–5.

Pilleron S, Rajaobelina K, Tabue Teguo M, Dartigues JF, Helmer C, Delcourt C, et al. Accumulation of advanced glycation end products evaluated by skin autofluorescence and incident frailty in older adults from the Bordeaux Three-City cohort. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(10):e0186087.

Tikkanen-Dolenc H, Waden J, Forsblom C, Harjutsalo V, Thorn LM, Saraheimo M, et al. Frequent and intensive physical activity reduces risk of cardiovascular events in type 1 diabetes. Diabetologia. 2017;60(3):574–80.

Draelos ZD, Yatskayer M, Raab S, Oresajo C. An evaluation of the effect of a topical product containing C-xyloside and blueberry extract on the appearance of type II diabetic skin. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2009;8(2):147–51.

Barat P, Cammas B, Lacoste A, Harambat J, Vautier V, Nacka F, et al. Advanced glycation end products in children with type 1 diabetes: family matters? Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):e1.

Uribarri J, Woodruff S, Goodman S, Cai W, Chen X, Pyzik R, et al. Advanced glycation end products in foods and a practical guide to their reduction in the diet. J Am Diet Assoc. 2010;110(6):911–6.

Authors’ contributions

Writting: CBB and VR, Patients’ inclusion and follow-up: FLC, LB, LA, MM, KM, data analyses: ACG, CH, CD, Review before submission: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

Yes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1.

Scatterplot for SAF over age.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Blanc-Bisson, C., Velayoudom-Cephise, F.L., Cougnard-Gregoire, A. et al. Skin autofluorescence predicts major adverse cardiovascular events in patients with type 1 diabetes: a 7-year follow-up study. Cardiovasc Diabetol 17, 82 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0718-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-018-0718-8