Abstract

Background

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is an evidence-based treatment for acute respiratory failure in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). However, suboptimal application of NIV in clinical practice, possibly due to poor guideline adherence, can impact patient outcomes. This study aims to evaluate guideline adherence to NIV for acute COPD exacerbations and explore its impact on mortality.

Methods

This retrospective study was performed in two Dutch medical centers from 2019 to 2021. All patients admitted to the pulmonary ward or intensive care unit with a COPD exacerbation were included. An indication for NIV was considered in the event of a respiratory acidosis.

Results

A total of 1162 admissions (668 unique patients) were included. NIV was started in 154 of the 204 admissions (76%) where NIV was indicated upon admission. Among 78 admissions where patients deteriorated later on, NIV was started in 51 admissions (65%). Considering patients not receiving NIV due to contra-indications or patient refusal, the overall guideline adherence rate was 82%. Common reasons for not starting NIV when indicated included no perceived signs of respiratory distress, opting for comfort care only, and choosing a watchful waiting approach. Better survival was observed in patients who received NIV when indicated compared to those who did not.

Conclusions

The adherence to guidelines regarding NIV initiation is good. Nevertheless, further improving NIV treatment in clinical practice could be achieved through training healthcare professionals to increase awareness and reduce reluctance in utilizing NIV. By addressing these factors, patient outcomes may be further enhanced.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) is an evidence-based treatment for patients with acute respiratory failure due to an exacerbation of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD). In COPD patients with acute hypercapnic respiratory failure, NIV improves gas exchange, reduces work of breathing and reduces length of hospital stay and mortality [1, 2]. Furthermore, when compared to invasive ventilation, NIV leads to fewer complications, such as ventilator related infections [3, 4]. These findings have resulted in guideline recommendations for the use of NIV in acute respiratory failure due to an exacerbation of COPD [5].

However, the real effectiveness of NIV in routine clinical practice is uncertain. Kaul et al. [6] performed a large observational multicenter study including 7529 COPD patients with an exacerbation. They found a higher in-hospital mortality rate among patients who received NIV in comparison to those who received conventional care, which contradicts the results of earlier performed randomized trials on which the guidelines regarding NIV are based. The same research group performed a follow-up study with 9716 patients to provide possible explanations for their relatively high mortality [7]. They suggested that this discrepancy might be explained by the fact that patients in clinical practice are more severely acidotic than patients included in the randomized trials. Another explanation for the difference in mortality rate might be that the guideline regarding NIV initiation is often not followed. The guideline states a clear indication for NIV during an exacerbation of COPD: moderate to severe respiratory acidosis in the arterial blood gas analysis (i.e. pH < 7.35 and partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) > 6.0 kPa) without contraindications. Despite this explicit indication, Roberts et al. [7] reported that both the initiation of NIV in patients with a metabolic acidosis and the non-initiation in patients with a respiratory acidosis were no exception. This is in agreement with another study by Roberts et al. [8], which showed that adherence to the guidelines concerning COPD exacerbations in general, and also specifically to NIV treatment during COPD exacerbations, is poor. They reported that only 51% of the patients who fulfilled the indications for NIV received NIV. Vice versa, they describe that 29% of all patients receiving NIV did not fulfil the criteria for NIV. Overall, earlier research suggests that the application of NIV is far from optimal in daily clinical practice, which may have detrimental effects on patient outcomes. However, due to the large cohorts in these studies, it was impossible to state the rationale behind the (non-)initiation of NIV and whether it was applied correctly at case-level, making it difficult to draw conclusions about the adherence to NIV guidelines. Furthermore, we wondered whether there could be relevant differences between countries, in this case, between the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.

Therefore, the goal of this study is to describe adherence to guidelines concerning NIV for acute COPD exacerbations in two medical centers in the Netherlands, and investigate its effect on mortality.

Methods

Study design

This retrospective study was performed in the departments of pulmonary diseases in two medical centers in the Netherlands: hospital A, an academic hospital, where screening took place between January 2019 and July 2021, and hospital B, a large non-university teaching hospital, where screening was conducted between April 2019 and January 2021.

Patients had to meet the following criteria to be included: a history of COPD and admission to the hospital with an exacerbation of COPD. History of COPD was based on prior pulmonary function tests, either performed in hospital or at the general practitioner’s practice. An exacerbation was defined as a period of worsening of symptoms treated with oral prednisolone and/or antibiotics. The only exclusion criterium was admittance to a department other than the pulmonary department or the intensive care unit.

The medical ethics committee of the University Medical Center Groningen examined the research protocol and decided that the study was not subject to the Dutch Research on Humans Subjects Act and waived the need for formal ethics approval and informed consent. However, to comply with local regulations, all living study participants were requested to declare any objection for data usage and absence of objection was regarded as their consent.

Data collection

One researcher collected data by analysing medical records that had already been gathered as part of standard clinical care. The following data were obtained and entered into a database (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Ill, USA): demographic characteristics, medical history, lab results, admission and treatment details, and mortality (in-hospital and 90 days after hospital discharge).

An indication for NIV was considered in the event of a respiratory acidosis (pH < 7.35 and pCO2 > 6.0 kPa) detected by the arterial or capillary blood gas analysis. The origin of the exacerbation was classified as infectious based on a positive bacterial culture or nasopharyngeal viral swab, or a high clinical suspicion of infection based on the patient’s symptoms, high level of C-reactive protein, and/or the identification of an infiltrate on chest radiograph. If there was an obvious non-infectious origin, such as exposure to irritants or neglecting the use of inhalation medication, the exacerbation was classified as non-infectious. In cases where neither of these origins applied, the origin was marked as unknown. The classification of co-morbidities involved a review of both medical history and medication use. The NIV protocol used at both hospitals is presented in the Supplementary Materials.

Statistics

Descriptive analyses were used to calculate adherence to guidelines. Results are given as median with interquartile range. Differences in numerical data were analysed using an unpaired t-test or Mann-Whitney U test, depending on their distribution. Comparison of categorical data were analysed by using Fisher’s exact test. Comparison of binary data were analysed by using logistics regression to calculate odds ratio, 95% confidence interval and p-value. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant. Mortality data were analysed for the first admission for each unique patient, since this outcome is limited to a single occurrence per individual.

Results

In total, 1162 admissions were included consisting of 668 unique patients. Baseline information of the study population and information regarding their hospitalisation is reported in Table 1 (see page 21).

Non-invasive ventilation at admission

In 1110 admissions (96%), an arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis was performed at admission. Reasons for not performing an ABG in the remaining 52 admissions were: failure to obtain an ABG (31%), admission via another medical specialty (10%), unknown (52%) or other (7%).

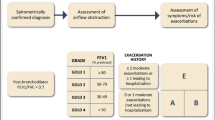

In 267 admissions (23% of all admissions), the inclusion criteria for NIV were met. The respiratory acidosis cleared in 63 admissions after initial treatment with bronchodilators and/or oxygen titration. In 154 of the remaining 204 admissions (76%), NIV was started. In 13 of the 50 admissions (26%) where NIV was indicated but not started, the reason for not starting was in agreement with the guidelines. Among the 895 admissions without an indication for NIV, NIV was initiated in 22 admissions (3%).

Figure 1 provides an overview of all admissions and presents the reasons for refraining from NIV when it is indicated and vice versa (all as far as deducible from the retrospective records). Details about NIV treatment at admission can be found in Table 2 (see page 22).

Non-invasive ventilation during hospitalization

In 101 admissions (9% of all admissions), the patient deteriorated during their hospital stay. This includes patients who had an indication for NIV earlier during their admission (n = 25), but irrespective of whether NIV was initiated at admission or not, all these patients achieved an arterial pH within the normal range without NIV before the onset of the deterioration. Of the 101 admissions, 78 met the inclusion criteria for NIV after an alteration in oxygen or bronchodilators. In 51 of the 78 admissions (65%), NIV was initiated. In 13 of the 27 admissions (48%) where NIV was indicated but not started, the reason for not starting was in agreement with the guidelines. Figure 2 shows an overview of admissions where patients later deteriorated and provides the reasons why NIV was not started while it was indicated. Details about the NIV treatment during hospitalization can be found in Table 3 (see page 23).

Mortality

The overall in-hospital and 90-day mortality rate for the cohort of 668 unique patients were 6% and 14%, respectively. In patients with an indication for NIV at admission, mortality at 90 days was significantly lower in patients who received NIV compared to patients who did not receive NIV due to reasons not in agreement with the guidelines (Table 4). The in-hospital mortality was not significantly different between these groups. In patients with an indication for NIV later during hospitalisation, no significant differences in mortality rates were seen between who received NIV and patients who did not receive NIV due to reasons not in agreement with the guidelines.

Furthermore, Table 4 shows that patients who were initiated on NIV at admission had a more severe hypercapnic acidosis than patients who did not receive NIV.

Variation in NIV treatment between centers

No difference in the initiation of NIV among indicated patients was observed between the centers, both when NIV was initiated at admission (hospital A vs. B: 78.2 vs. 74.5%, p = 0.588, OR 0.815 [0.390–1.706]) and later during hospitalisation (hospital A vs. B: 60.9 vs. 67.3%, p = 0.588, OR 1.321 [0.482–3.625]). Table 2 provides details on NIV treatment administered upon admission at both centers, showing higher inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) levels and longer treatment duration in hospital A compared to hospital B. Furthermore, a significant difference was seen in the place of NIV treatment and the reasons for NIV termination between both centers. No differences were found between the two centers for in-hospital mortality (hospital A vs. B: 18.2 vs. 11.1%, p = 0.380, OR 0.563 [0.156–2.030]) and 90-day mortality (hospital A vs. B: 24.2 vs. 25.0%, p = 0.939, OR 1.042 [0.365–2.972]) in patients where NIV was initiated at admission. Table 3 contains information on NIV treatment initiated later during hospitalization at both centers, revealing lower NIV pressures were given in hospital B compared to hospital A. No differences were found between the two centers for in-hospital mortality (hospital A vs. B: 10.0 vs. 27.8%, p = 0.292, OR 3.461 [0.344–34.843] and 90-day mortality (hospital A vs. B: 50.0 vs. 44.4%, p = 0.778, OR 0.800 [0.170–3.767]) in patients were NIV was initiated later during hospitalisation. Additional information regarding patient characteristics of all patients who received NIV, specified per hospital, can be found in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

Discussion

This is the first study describing the use of NIV for acute COPD exacerbations in two medical centers in the Netherlands. Our findings demonstrate that NIV was initiated in 76% of the admissions where NIV was indicated upon admission, while this was the case in 65% of the admissions where the patient deteriorated later during hospitalization.

Previous studies evaluating the adherence to NIV guidelines at admission in clinical practice outside the Netherlands have shown variable results, with guideline rates ranging from 24 to 74% [7,8,9,10,11]. One prior survey study was performed in the Netherlands and showed a guideline adherence rate of 65% [12]. Our results showed that NIV was initiated in 76% of the admissions where NIV was indicated patients at admission. If we take into account patients who were not initiated on NIV due to reasons in line with the guidelines, the adherence rate concerning NIV initiation at admission reached 82%, indicating a relatively high level of adherence to guidelines. Vice versa, our findings show that the initiation of NIV in patients without an indication is infrequent. In only 2.5% of the admissions where NIV was not indicated, NIV was started. Out of those admissions, only half received NIV against the guidelines. These outcomes are superior compared to previous studies [7, 8]. Additionally, in terms of obtaining an ABG at admission, our findings exceed reported rates in literature [7, 8, 10, 11, 13,14,15]. A possible explanation for these higher adherence rates might be that our study was performed in two large centers with clear protocols and considerable experience in the field of NIV. Furthermore, the availability of well-educated staff and NIV facilities may play a role.

To our knowledge, only one study [7] investigated the adherence to NIV guidelines when patients deteriorated later on during hospitalisation. They included patients who were admitted with a normal pH and developed an acidosis later during hospitalisation and they showed an adherence rate of 47% in this group. Again, our results show a higher level of adherence to guidelines. Our study demonstrated that NIV was initiated in 65% of the admissions where patients had a NIV indication later during hospitalisation. Considering patients who were not given NIV because of a contra-indication or because patients refused, the adherence rate in patients who deteriorated later on during hospitalisation reaches 82%, matching the adherence rate observed at admission. In patients who deteriorated later, the rationale for the non-initiation of NIV appears to be better described in the medical records, implying that the medical staff is more aware of the indication and possible need for NIV during hospitalisation than at admission.

The mortality rates in both the overall population and specifically in the group of patients who were treated with NIV are consistent with those reported in prior research on acute exacerbations of COPD [13, 16,17,18,19]. In patients with an indication for NIV at admission, the group of patients who did not receive NIV due to reasons not according to the guidelines had a worse survival compared to those who received NIV. This is noteworthy because these patients had a less severe respiratory acidosis, which is expected to correspond to lower mortality rates. These findings may emphasize the importance of NIV initiation when indicated. In addition, the absolute mortality rates were higher in patients who later deteriorated during hospitalisation compared to those who required NIV upon admission. It appears that patients who later deteriorated have worse outcomes and that these patients have less benefit of NIV compared to patients with an NIV indication at admission, as also previously reported in literature [7, 20]. This worse outcome is also reflected in the large number of patients who were initiated on NIV during hospitalisation but terminated NIV due to the transfer to invasive ventilation or to receive comfort care only.

While no disparities in NIV initiation were observed between centers, notable differences were identified in the NIV treatment between both participating centers. The variation in NIV duration started at admission can be clarified by the difference in protocols between both hospitals in the manner of weaning from NIV. Hospital A employs a stepwise reduction by gradually reducing the number of hours per day on the ventilator while hospital B immediately withdraws NIV once the respiratory acidosis has been resolved. Since mortality rates were not affected, these findings support earlier reported results that a stepwise reduction of NIV is equally effective compared to an immediate withdrawal [21, 22]. Next to the length of NIV treatment, the most noticeable differences between the two centers revolved around the place of NIV treatment and the reasons for NIV termination. Notably, hospital A treated patients more frequently on the pulmonary ward rather than in the ICU, which can be possibly attributed to logistical variations between the centers. Additionally, the difference in reasons for NIV termination is primarily explained by the fact that hospital A initiated more patients on chronic NIV than hospital B. This observation seems logical since hospital A is an academic hospital with a specialized expertise in chronic ventilation. Despite these disparities in NIV treatment practices, the mortality rates between the centers did not show any significant differences.

Although this study shows a relatively good adherence to NIV guidelines, there is still potential for enhancing NIV treatment in clinical practice. This is evident from the subset of patients who met the criteria for NIV treatment but did not receive it due to reasons contrary to guidelines. The most benefit can probably be gained by improving the adherence to NIV guidelines at admission, since nearly three-quarters of patients who met the criteria for NIV treatment but did not receive it at admission, did not have a justifiable reason for its non-initiation. In a large portion of these patients, the reason was not registered or the possibility of NIV was not mentioned in the medical records. This may indicate unawareness among healthcare providers at the emergency department about the indication and benefit of NIV in acute COPD exacerbations, and could be improved with more training. Furthermore, healthcare providers seem to be reluctant to initiate NIV when indicated, as suggested by several reasons provided for non-initiation such as watchful waiting and no increased work of breathing. In order to improve NIV use in clinical practice, further research should focus on training and on investigating why healthcare providers are reluctant to use NIV in clinical practice.

This study has several limitations. First of all, this study was performed in only two centres, which challenges the extrapolation of the results to the general population of hospitalized COPD patients, especially when considering the potential variability between centers even in the same country [13, 23]. On the other hand, both an academic and a non-university center were included. Second, due to its retrospective design, the study is limited by some degree of missing data, for example reasons why NIV was not started despite being indicated. It is plausible that NIV treatment was considered but not initiated due to justifiable reasons, but that this rationale was not documented in the medical records. And last, the classification of patients who did not receive NIV when it was indicated into two categories (on reasons in agreement with and contrary to the guidelines) may be open to debate. Especially, the rationale ‘to only start comfort care’ could be placed into either one of those categories, depending on local protocols. Since our local NIV protocol does not state comfort care as a contraindication for NIV initiation, we categorized it as a reason contrary to guidelines. Another justification for placing it in that category is that previous research has demonstrated the effectiveness of NIV in alleviating dyspnoea in end-stage disease patients [24, 25].

In conclusion, we showed a good adherence to NIV guidelines during acute exacerbations of COPD in two medical centers in the Netherlands. Failure to initiate NIV when indicated at admission may have a detrimental effect on patient outcomes, highlighting the importance of NIV initiation in such cases.

Data availability

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- ABG:

-

arterial blood gas

- BMI:

-

body mass index

- COPD:

-

chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CRP:

-

C-reactive protein

- EPAP:

-

expiratory airway pressure

- ER:

-

emergency room

- FEV1:

-

forced expiratory volume in 1 s

- FVC:

-

forced vital capacity

- ICU:

-

intensive care unit

- IPAP:

-

inspiratory positive airway

- NA:

-

not applicable

- NIV:

-

non-invasive ventilation

- PaCO2 :

-

partial pressure of carbon dioxide

- PaO2 :

-

partial pressure of oxygen

References

Guideline B. Non-invasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. Thorax. 2002;57(3):192–211.

Osadnik CR et al. Non-invasive ventilation for the management of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure due to exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2017(7).

Nava S, Hill N. Non-invasive ventilation in acute respiratory failure. The Lancet. 2009;374(9685):250–9.

Squadrone E, et al. Noninvasive vs invasive ventilation in COPD patients with severe acute respiratory failure deemed to require ventilatory assistance. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30(7):1303–10.

Rochwerg B et al. Official ERS/ATS clinical practice guidelines: noninvasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure. Eur Respir J, 2017. 50(2).

Kaul S et al. Non-invasive ventilation (NIV) in the clinical management of acute COPD in 233 UK hospitals: results from the RCP/BTS 2003 National COPD Audit COPD: Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, 2009. 6(3): p. 171–176.

Roberts C, et al. Acidosis, non-invasive ventilation and mortality in hospitalised COPD exacerbations. Thorax. 2011;66(1):43–8.

Roberts CM, et al. European hospital adherence to GOLD recommendations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) exacerbation admissions. Thorax. 2013;68(12):1169–71.

Considine J, Botti M, Thomas S. Emergency department management of exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: audit of compliance with evidence-based guidelines. Intern Med J. 2011;41(1a):48–54.

Gerber A, et al. Compliance with a COPD bundle of care in an australian emergency department: a cohort study. Clin Respir J. 2018;12(2):706–11.

Pretto JJ, et al. Multicentre audit of inpatient management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: comparison with clinical guidelines. Intern Med J. 2012;42(4):380–7.

Hilderink J, et al. Non-invasive ventilation for acute respiratory failure due to exacerbation of COPD; a national survey in the Netherlands on the adherence to the dutch guideline. Eur Respir J. 2014;44(Suppl 58):P2969.

Liaaen ED, Henriksen AH, Stenfors N. A scandinavian audit of hospitalizations for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med. 2010;104(9):1304–9.

Sha J, et al. Hospitalised exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: adherence to guideline recommendations in an australian teaching hospital. Intern Med J. 2020;50(4):453–9.

Cydulka RK, et al. Emergency department management of acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in the elderly: the Multicenter Airway Research collaboration. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(7):908–16.

Ambrosino N, Vagheggini G. Non-invasive ventilation in exacerbations of COPD. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2007;2(4):471–6.

Hoogendoorn M, et al. Case fatality of COPD exacerbations: a meta-analysis and statistical modelling approach. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(3):508–15.

Price LC, et al. UK National COPD Audit 2003: impact of hospital resources and organisation of care on patient outcome following admission for acute COPD exacerbation. Thorax. 2006;61(10):837–42.

Sprooten RTM, et al. Predictors for long-term mortality in COPD patients requiring non-invasive positive pressure ventilation for the treatment of acute respiratory failure. Clin Respir J. 2020;14(12):1144–52.

Trethewey SP, et al. Late presentation of acute hypercapnic respiratory failure carries a high mortality risk in COPD patients treated with ward-based NIV. Respir Med. 2019;151:128–32.

Sellares J et al. Discontinuing noninvasive ventilation in severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Respir J, 2017. 50(1).

Lun CT et al. A randomised controlled trial comparing stepwise < em > versus immediate withdrawal from non-invasive ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients recovering from acute hypercapnic respiratory failure European Respiratory Journal, 2012. 40(Suppl 56): p. P2062.

Hosker H, et al. Variability in the organisation and management of hospital care for COPD exacerbations in the UK. Respir Med. 2007;101(4):754–61.

Cuomo A, et al. Noninvasive mechanical ventilation as a palliative treatment of acute respiratory failure in patients with end-stage solid cancer. Palliat Med. 2004;18(7):602–10.

Nava S, et al. Palliative use of non-invasive ventilation in end-of-life patients with solid tumours: a randomised feasibility trial. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(3):219–27.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JE: conceptualization, methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review & editing. JV: methodology, writing – review & editing. AvdP: investigation, resources, writing – review & editing. CvD: investigation, resources, writing – review & editing. PV: investigation, resources, writing – review & editing. HAMK: methodology, writing – review & editing. PJW: methodology, writing – review & editing. MLD: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing – review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J. Elshof reports grants and speaking fees from Vivisol B.V., and grants from Fisher & Paykel, outside the submitted work. P.J. Wijkstra reports grants and consulting fees from Philips B.V., grants from Resmed Ltd., and a leadership role (treasurer) in the ERS board, outside the submitted work. M.L. Duiverman reports grants from Philips B.V., Fisher & Paykel, Vivisol B.V., Resmed Ltd. and Löwenstein B.V., speaking fees from Vivisol B.V., Resmed Ltd., Novartis, Chiesi, Breas and AstraZeneca, and a leadership role (chair group NIV) in ERS assembly 2. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The need for formal ethics approval and informed consent was waived by the medical ethics committee of the University Medical Center Groningen.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Additional file 1

: Table S1. Description of data: Patient characteristics of patients who were initiated on NIV for acute respiratory failure, specified per center.

Additional file 2

: Non-invasive ventilation protocol. Protocol for non-invasive ventilation in patients with acute respiratory insufficiency due to a COPD exacerbation.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Elshof, J., Vonk, J.M., van der Pouw, A. et al. Clinical practice of non-invasive ventilation for acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Res 24, 208 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02507-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-023-02507-1