Abstract

Background

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is projected to become the third cause of mortality worldwide. COPD shares several pathophysiological mechanisms with cardiovascular disease, especially atherosclerosis. However, no definite answers are available on the prognostic role of COPD in the setting of ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), especially during COVID-19 pandemic, among patients undergoing primary angioplasty, that is therefore the aim of the current study.

Methods

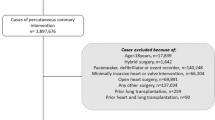

In the ISACS-STEMI COVID-19 registry we included retrospectively patients with STEMI treated with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) between March and June of 2019 and 2020 from 109 high-volume primary PCI centers in 4 continents.

Results

A total of 15,686 patients were included in this analysis. Of them, 810 (5.2%) subjects had a COPD diagnosis. They were more often elderly and with a more pronounced cardiovascular risk profile. No preminent procedural dissimilarities were noticed except for a lower proportion of dual antiplatelet therapy at discharge among COPD patients (98.9% vs. 98.1%, P = 0.038). With regards to short-term fatal outcomes, both in-hospital and 30-days mortality occurred more frequently among COPD patients, similarly in pre-COVID-19 and COVID-19 era. However, after adjustment for main baseline differences, COPD did not result as independent predictor for in-hospital death (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.913[0.658–1.266], P = 0.585) nor for 30-days mortality (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.850 [0.620–1.164], P = 0.310). No significant differences were detected in terms of SARS-CoV-2 positivity between the two groups.

Conclusion

This is one of the largest studies investigating characteristics and outcome of COPD patients with STEMI undergoing primary angioplasty, especially during COVID pandemic. COPD was associated with significantly higher rates of in-hospital and 30-days mortality. However, this association disappeared after adjustment for baseline characteristics. Furthermore, COPD did not significantly affect SARS-CoV-2 positivity.

Trial registration number: NCT 04412655 (2nd June 2020).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) has been estimated affecting more than 200 million people worldwide, representing the fourth highest cause of death in the world, with a projection to be the third leading cause of death in next years [1]. It represents a chronic inflammatory process affecting airways and lung parenchyma leading to an irreversible or partly reversible airflow obstruction [2]. Main risk factor is constituted by cigarette smoking, that is also crucial in promoting atherosclerosis. From a pathological point of view COPD and atherosclerosis share a pro-inflammatory environmental, conditioning cardiovascular system by endothelial dysfunction and increased platelet activation: impairment of the equilibrium in vessel homeostasis promotes plaque development and instability which are further aggravated by enhanced platelet reactivity.

This is reflected on the clinical side, where COPD patients are recognized at higher risk of cardiovascular diseases and mortality [3, 4]. Moreover, up to 17% of patients admitted for an acute myocardial infarction is affected by COPD [5]. Previous investigations showed potential negative impact of COPD on outcome of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) [6, 7], even if scant results were reported in the specific setting of ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), that deserves a fast mechanical reperfusion with primary PCI [8]. Contrasting findings have been described in relation to COPD impact on short-term mortality in STEMI patients, without conclusive sentence [9, 10]. In addition, most of prior evidence has been achieved a remarkable number of years ago, with a potential reduced validity nowadays, given the improvements in the management of acute cardiovascular diseases. Furthermore, last year was characterized by the outbreak of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, that deeply impacted in the world health care systems. Alongside the systemic involvement of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection, lungs constitute the main involved organs with clinical manifestations ranging from mild flu-like symptoms to acute respiratory distress syndrome [11]. COPD makes patients more prone to respiratory tract infection, especially of viral etiology, and it was demonstrated conferring higher probability of poor outcomes in COVID-19 patients [12].

Therefore, we aimed to inquire from a large, contemporary, multicenter registry of STEMI patients if COPD diagnosis at hospital admission could be deemed a risk factor of adverse outcome, especially during COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Study design and population

Study population is constituted by patients enrolled in the ISACS-STEMI COVID-19 (NCT 04412655), a retrospective multicenter registry including STEMI patients enrolled by 109 high-volume primary PCI centers from Europe, Latin America, South-East Asia and North-Africa. This study was conducted to compare STEMI patients treated from March 1st until June 30th of 2019 with those admitted within the same period of 2020. We included patients treated within 48 h from symptoms onset. We did not exclude those patients undergoing mechanical revascularization after failed thrombolysis (rescue angioplasty).

Collected baseline characteristics included demographic, clinical, procedural data, data on total ischemia time, door-to-balloon time, referral to primary PCI facility and PCI procedural data. COPD diagnosis was determined at admission according to international guidelines society [2]. The outcomes of interest were all-cause in-hospital mortality and all-cause mortality at 30 days. Follow-up data were obtained from outpatients' visit records or by telephone call.

The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of AOU Maggiore della Carità, Novara. Detailed data have previously been provided [13, 14].

Statistics

All analyses were performed by using SPSS Statistics Software 23.0 (IBM SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois). Patients were grouped according to COPD diagnosis. Absolute frequencies and percentages were used for categorical variables. Conversely, continuous variables were reported using median and interquartile range. Normal distribution of continuous variables was tested by the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Chi-square test was adopted for categorical variable, while ANOVA or Mann–Whitney test, as appropriate, were used for continuous variables.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the association of COPD with in-hospital and 30-day mortality and SARS-CoV-2 infection after adjustment for baseline confounding factors. All significant variable (set at a P‐value < 0.1) were entered in block into the model. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The data coordinating center was established at the Eastern Piedmont University, Novara, Italy.

Results

A total of 15,686 patients admitted for STEMI and undergoing mechanical reperfusion were included. Of them, 810 (5.2%) patients were affected by COPD, while 14,876 (94.2%) patients were not. Table 1 summarizes baseline features of the two groups. COPD patients displayed a higher cardiovascular risk profile than non-COPD. In particular, they were older, active smokers, more frequently affected by hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, with a history of prior STEMI and PCI. A higher percentage of COPD patients compared to non-COPD was from Europe with consequent lower fraction from South East Asia and North Africa. Differences neither in referral to hospital for primary PCI, nor in time delays were detected between COPD and non-COPD patients, that were more frequently admitted for anterior STEMI but less often in cardiogenic shock.

Angiographic and procedural characteristics are summarized in Table 2. No differences in stenting and use of drug-eluting stent were found, as well as in post-procedural TIMI 3 flow, Gp IIb-IIIa inhibitors, Cangrelor and Bivalirudin use. A numerically higher proportion of non-COPD patients received dual antiplatelet therapy after the procedure compared to COPD patients (98.9% vs. 98.1%, P = 0.038), while no difference was present regarding the use renin angiotensin system inhibitors during the hospitalization (56.8% vs. 54.7%, respectively, P = 0.232).

A similar percentage of SARS-CoV-2 positive patients between the two groups was recognized (1.0% vs 0.7% in COPD and non-COPD patients, respectively, P = 0.162).

A significant higher rate of mortality was experienced by COPD patients than ones without, both considering in-hospital (7.5% vs 5.8%, respectively, P = 0.041) and 30-day (9.4% vs 7.2%, respectively, P = 0.022) mortality (Fig. 1). Similar results were observed when a separate analysis was conducted in 2019 (pre-COVID) (in-Hospital mortality: 7% vs 5.2%, p = 0.20; 30-day mortality: 8.9% vs 6.4%, p = 0.053) and 2020 (COVID-19 pandemic) (in-hospital mortality 8.2% vs 6.5%, p = 0.10; 30-day mortality: 10.1% vs 8%, p = 0.170) (Fig. 2). SARS-Cov-2 positivity was associated with a significantly higher in-hospital and 30 mortality in both COPD and non-COPD patients (Fig. 3).

The detrimental relationship between COPD and short-term mortality was not confirmed after the adjustment for all the confounding baseline and procedural characteristics (age > 75 years, diabetes, active smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, previous STEMI, previous PCI, geographic area, cardiogenic shock, anterior MI, radial access, in-stent thrombosis, pre-procedural TIMI flow, dual antiplatelet therapy), neither for in-hospital (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 0.91 [0.66–1.27], P = 0.58) nor for 30-day mortality (adjusted HR [95% CI] = 0.85 [0.62–1.16], P = 0.31).

Discussion

Main findings from our large, multicenter, contemporary registry of STEMI patients are consistent with a low but not negligible percentage of patients with COPD. They displayed a significant higher baseline cardiovascular risk profile that portended an increase rate of in-hospital and short-term mortality. However, after adjustment for baseline clinical confounders, COPD did not result an independent predictor of fatal outcomes.

The strict relationship between lung and heart is well known, even if the mechanisms of this interplay are less intuitive and not fully delineated, especially on the pathological side: of course, sharing two key risk factors, age and cigarette smoking, enforces the link between COPD and ischemic heart disease. However, during last years the paradigm of COPD as localized inflammatory disease has shifted to systemic involvement, driven by the evidences of higher level of C-reactive protein, fibrinogen and pro-inflammatory cytokines [15, 16]. Together with oxidative stress and the consequent endothelial dysfunction and arterial stiffness, COPD presence meaningfully contributes to atherosclerotic disease progression. Moreover, plaque stability is altered by enhanced levels of matrix metalloproteinases, and the concomitant higher platelet activation favors thrombus formation [17, 18].

Results from clinical studies have shown a prevalence of coronary artery disease among COPD patients ranging from 10 to 38% [19, 20] with enhanced cardiovascular mortality following an episode of acute exacerbation [21]. Furthermore, as outlined by Campo et al., among COPD patients referred for an acute exacerbation, the increased risk of adverse cardiac events at follow-up was even worse in patients without history of ischemic heart disease [22].

Similarly, individuals with acute myocardial infarction are more prone to adverse outcomes if a concomitant COPD diagnosis was present [23]. Data from a large registry in the United Kingdom, after correction for other cardiovascular risk factor, suggests increased risk of mortality among COPD patients compared to ones without after an acute myocardial infarction [24] The same authors however underscored an appreciable reduction, even still significant, of the risk of mortality for both STEMI and Non-STEMI, after adjustment for confounders. In this way, Serban et al. argued that the increase of mortality after a MI in COPD patients was more likely due to non-optimal medical therapy rather than disease-specific impact [25], and Andell et al. underscored the potential delay in revascularization treatment as additional detrimental issue in COPD patients [26].

Further distinctions have been enlightened by prior studies with regards of STEMI or Non-STEMI presentation. Enriquez et colleagues have shown no significant independent role of COPD into prediction of in-hospital mortality among STEMI patients, whilst it was exclusive of among those with Non-STEMI [27]. Moreover, Lazzeri et al. have found in more than 800 STEMI patients no impact of COPD in short-term mortality at multivariate analysis [10]. Reasons of discrepancies in literature findings could be sought in the fact that most of prior studies was conducted before the 2010 [23], thus earlier than last improvements achieved in primary PCI for STEMI patients [28,29,30]. Updated data defining the role and impact of COPD in contemporary large cohort of patients admitted for STEMI are therefore lacking.

In our large multicenter cohort of patients admitted for STEMI a relatively limited proportion of subjects diagnosed with COPD. Their enhanced cardiovascular risk of COPD patients was made-up by more frequent co-presence of active smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, prior acute cardiac ischemic event, in line with previous reports on the topic [31]. Moreover, advanced age and presentation with cardiogenic shock portrayed patients with COPD compared to those without, while no differences in cardiac arrest as clinical presentation was detected, similarly to prior studies [32].

COPD patients were more prone to fatal outcomes displaying both for in-hospital and 30-day mortality a higher percentage that patients without COPD. However, these significant differences were not confirmed at multivariate logistic regression analyses that did not show an independent role of COPD diagnosis to predict short-term mortality. Our findings are inserted in the controversy still persistent on whatever COPD might represent a risk factor unassociated with others or if it reflects the burden of comorbidities linked to this condition [25, 33]. Additional issues raised by other authors concerned the treatment provided to COPD patients with acute MI: in fact, the part of COPD patients with STEMI displaying the lower risk of adverse outcomes was identified being on appropriate treatment for the lung disease [34]. Also Stefan et al. reported that COPD patients still continue to receive less frequent evidence-base therapy after acute MI, despite signals of amelioration are noticeable across years [5]. In our cohort we did not appreciate any differences in term of use rates of renin angiotensin system inhibitors, cornerstone of drug therapy after STEMI [35].

Additional value of this investigation is the crucial information regarding the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic impact, especially considering our inspection of a lung disease. COPD is known providing higher risk of infection: lung inflammation, airflow obstruction, and impaired clearance of respiratory virus are elements supporting a greater risk for COVID-19 and its severity among COPD patients [2, 36,37,38]. Data from a large meta-analysis confirmed an increased odds of adverse outcomes, including mortality among COVID-19 with already diagnosed COPD compared to ones without [12]. Also Aveyard et al. have reported COPD patients at higher risk of severe COVID-19 disease, even if the mortality rate for SARS-CoV-2 infection compared to other causes, was not significant in young adults, while in older COPD patients cardiovascular and other causes consistently have contributed the most to mortality [39]. Notably, in our cohort, after inquiring separately data of 2019 and 2020, the worse outcome of COPD patients was similarly observed in both groups, even though the adverse outcomes differences did not reach the significance. Main explanation concerns the reduced statistical power after splitting patients in the two cohorts according to the year. In addition, with respect of SARS-CoV-2 positivity, we reported similar, low rates between patients with and without COPD.

Findings from our large multicenter registry provide an updated snapshot of the impact of COPD on short term outcomes in the acute setting of STEMI. Based on our data, COPD does not represent itself an independent negative prognostic determinant. Therefore, COPD should not be used for risk stratification and COPD patients should not be object of more intensive and aggressive therapies as compared to the standard care for STEMI patients. Dedicated, prospective studies may offer definite and comprehensive answers about the COPD contribution on mortality after an acute MI.

Limitations

Our findings should be viewed in light of some limitations. The retrospective non-randomized design of our study precludes to definite answer on the impact of COPD on morality in patients experiencing a STEMI. Not all variable of interest could have been collected, reducing the allowed investigations.

The diagnosis of COPD was based on medical records of every patients, and systematic confirmation through pulmonary function tests in case of suspect of doubt diagnosis was not performed. As well, we were not able to classify COPD patients according to their inflammatory endotype [40], that have surely provided more comprehensive findings on relationship between COPD and STEMI.

The ISACS-STEMI registry was not conceived to examine the role of COPD, therefore data are missing on complete in-hospital and post-discharge drug treatment regimens, specifically regarding the COPD, preventing analyses on essential aspect of the treated topic [25], even if the high number of patients included, more than 10-times of the majority of prior investigations, can make the findings pretty confident.

Conclusions

This is one of the largest studies investigating characteristics and outcome of COPD patients with STEMI undergoing primary angioplasty, especially during COVID-19 pandemic. COPD was associated with significantly higher rates of in-hospital and 30-days mortality. However, this association disappeared after adjustment for baseline characteristics. Furthermore, COPD did not significantly affect SARS-CoV-2 positivity.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease—2019

- PCI:

-

Percutaneous coronary intervention

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- STEMI:

-

ST-elevation myocardial infarction

References

Mannino DM, Higuchi K, Yu T-C, Zhou H, Li Y, Tian H, et al. Economic burden of COPD in the presence of comorbidities. Chest. 2015;148(1):138–50.

Singh D, Agusti A, Anzueto A, Barnes PJ, Bourbeau J, Celli BR, Criner GJ, Frith P, Halpin DMG, Han M, López Varela MV, Martinez F, Montes de Oca M, Papi A, Pavord ID, Roche N, Sin DD, Stockley R, Vestbo J, Wedzicha JA, Vogelmeier C. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease: the GOLD science committee report 2019. Eur Respir J. 2019 May 18;53(5):1900164

Bellocchia M, Masoero M, Ciuffreda A, Croce S, Vaudano A, Torchio R, et al. Predictors of cardiovascular disease in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Multidiscip Respir Med. 2013;8(1):58.

Cheng S-L, Chan M-C, Wang C-C, Lin C-H, Wang H-C, Hsu J-Y, et al. COPD in Taiwan: a national epidemiology survey. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:2459–67.

Stefan MS, Bannuru RR, Lessard D, Gore JM, Lindenauer PK, Goldberg RJ. The impact of COPD on management and outcomes of patients hospitalized with acute myocardial infarction. Chest. 2012;141(6):1441–8.

Su TH, Chang SH, Chen PC, Chan YL. Temporal Trends in Treatment and Outcomes of Acute Myocardial Infarction in Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease: A Nationwide Population-Based Observational Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(3):e004525.

Tomaniak M, Chichareon P, Takahashi K, Kogame N, Modolo R, Chang CC, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and dyspnoea on clinical outcomes in ticagrelor treated patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention in the randomized GLOBAL LEADERS trial. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Pharmacother. 2020;6(4):222–30.

De Luca G, Suryapranata H, Ottervanger JP, Antman EM. Time delay to treatment and mortality in primary angioplasty for acute myocardial infarction: every minute of delay counts. Circulation. 2004;109(10):1223–5.

Wakabayashi K, Gonzalez MA, Delhaye C, Ben-Dor I, Maluenda G, Collins SD, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on acute-phase outcome of myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2010;106(3):305–9.

Lazzeri C, Valente S, Attanà P, Chiostri M, Picariello C, Gensini GF. The prognostic role of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in ST-elevation myocardial infarction after primary angioplasty. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2013;20(3):392–8.

Esakandari H, Nabi-Afjadi M, Fakkari-Afjadi J, Farahmandian N, Miresmaeili S-M, Bahreini E. A comprehensive review of COVID-19 characteristics. Biol Proced Online. 2020;22:19.

Gerayeli FV, Milne S, Cheung C, Li X, Yang CWT, Tam A, et al. COPD and the risk of poor outcomes in COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;33: 100789.

De Luca G, Cercek M, Jensen LO, Vavlukis M, Calmac L, Johnson T, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic and diabetes on mechanical reperfusion in patients with STEMI: insights from the ISACS STEMI COVID 19 Registry. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19(1):215.

De Luca G, Verdoia M, Cercek M, Jensen LO, Vavlukis M, Calmac L, et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mechanical reperfusion for patients with STEMI. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(20):2321–30.

Wedzicha JA, Seemungal TA, MacCallum PK, Paul EA, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, et al. Acute exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are accompanied by elevations of plasma fibrinogen and serum IL-6 levels. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84(2):210–5.

Sin DD, Man SFP. Why are patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at increased risk of cardiovascular diseases? The potential role of systemic inflammation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Circulation. 2003;107(11):1514–9.

Mallah H, Ball S, Sekhon J, Parmar K, Nugent K. Platelets in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: an update on pathophysiology and implications for antiplatelet therapy. Respir Med. 2020;171: 106098.

Ashitani J-I, Mukae H, Arimura Y, Matsukura S. Elevated plasma procoagulant and fibrinolytic markers in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Intern Med. 2002;41(3):181–5.

Mapel DW, Dedrick D, Davis K. Trends and cardiovascular co-morbidities of COPD patients in the Veterans Administration Medical System, 1991–1999. COPD. 2005;2(1):35–41.

Curkendall SM, DeLuise C, Jones JK, Lanes S, Stang MR, Goehring E, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Saskatchewan Canada cardiovascular disease in COPD patients. Ann Epidemiol. 2006;16(1):63–70.

Pavasini R, D’Ascenzo F, Campo G, Biscaglia S, Ferri A, Contoli M, et al. Cardiac troponin elevation predicts all-cause mortality in patients with acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol. 2015;191:187–93.

Campo G, Pavasini R, Malagù M, Punzetti S, Napoli N, Guerzoni F, et al. Relationship between troponin elevation, cardiovascular history and adverse events in patients with acute exacerbation of COPD. COPD. 2015;12(5):560–7.

Goedemans L, Bax JJ, Delgado V. COPD and acute myocardial infarction. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29(156): 190139.

Rothnie KJ, Smeeth L, Herrett E, Pearce N, Hemingway H, Wedzicha J, et al. Closing the mortality gap after a myocardial infarction in people with and without chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Heart. 2015;101(14):1103–10.

Șerban RC, Hadadi L, Șuș I, Lakatos EK, Demjen Z, Scridon A. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on in-hospital morbidity and mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Int J Cardiol. 2017;243:437–42.

Andell P, Koul S, Martinsson A, Sundström J, Jernberg T, Smith JG, James S, Lindahl B, Erlinge D. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on morbidity and mortality after myocardial infarction. Open Heart. 2014;1(1):e000002.

Enriquez JR, de Lemos JA, Parikh SV, Peng SA, Spertus JA, Holper EM, et al. Association of chronic lung disease with treatments and outcomes patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am Heart J. 2013;165(1):43–9.

De Luca G, Schaffer A, Wirianta J, Suryapranata H. Comprehensive meta-analysis of radial vs femoral approach in primary angioplasty for STEMI. Int J Cardiol. 2013;168(3):2070–81.

De Luca G, Dirksen MT, Spaulding C, Kelbaek H, Schalij M, Thuesen L, et al. Drug-eluting vs bare-metal stents in primary angioplasty: a pooled patient-level meta-analysis of randomized trials. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(8):611–216212.

De Luca G, Navarese EP, Suryapranata H. A meta-analytic overview of thrombectomy during primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol. 2013;166(3):606–12.

Carter P, Lagan J, Fortune C, Bhatt DL, Vestbo J, Niven R, et al. Association of cardiovascular disease with respiratory disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(17):2166–77.

Andell P, Koul S, Martinsson A, Sundström J, Jernberg T, Smith JG, et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on morbidity and mortality after myocardial infarction. Open Heart. 2014;1(1): e000002.

Hadi HAR, Zubaid M, Mahmeed WA, El-Menyar AA, Ridha M, Alsheikh-Ali AA, et al. Prevalence and prognosis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease among 8167 Middle Eastern patients with acute coronary syndrome. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33(4):228–35.

Contoli M, Campo G, Pavasini R, Marchi I, Pauletti A, Balla C, et al. Inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting bronchodilator treatment mitigates STEMI clinical presentation in COPD patients. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;47:82–6.

Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119–77.

Herr C, Beisswenger C, Hess C, Kandler K, Suttorp N, Welte T, et al. Suppression of pulmonary innate host defence in smokers. Thorax. 2009;64(2):144–9.

Milne S, Yang CX, Timens W, Bossé Y, Sin DD. SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 gene expression and RAAS inhibitors. Lancet Respir Med. 2020;8(6):e50–1.

Mallia P, Message SD, Gielen V, Contoli M, Gray K, Kebadze T, et al. Experimental rhinovirus infection as a human model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183(6):734–42.

Aveyard P, Gao M, Lindson N, Hartmann-Boyce J, Watkinson P, Young D, et al. Association between pre-existing respiratory disease and its treatment, and severe COVID-19: a population cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021;9(8):909–23.

Barnes PJ. Inflammatory endotypes in COPD. Allergy. 2019;74(7):1249–56.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

GDL: conceptualization; data curation; investigation; formal analysis; review of the manuscript; MV: supervision, investigation; validation, project administration; MN: writing the manuscript, visualization; AAL, AAO, AGB, AHY, AK, AL, AQ, AR, ARR, AS, AT, AWSL, BF, BS, BU, CAS, CEU, CM, CVB, DA, DAJ, DCO, DM, EF, EK, FBO, FCCT, FSDU, FV, FZ, GCai, GCas, GCi, GCo, GGab, GGal, GK, GPe, GPa, GRF, HL, HLK, HP, HS, IB, ILML, JABS, JK, JLDG, JM, JPB, JSF, JTB, KUM, LC, LD, LM, LOJ, LV, MA, MAB, MB, MC, MD, MK, MKL, MMe, MMi, MV, NB, PD, PHL, PK, PL, RDMJ, RP, RT, RZ, SM, SO, SS, TK, VF, VGa, VGu, VMBM, VSJ, XC, XFR, YA and ZZ: data curation; investigation. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study is a retrospective registry, with anonymized data collection. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Committee of AOU Maggiore della Carità, Novara. The need to notify or ask for approval to the local ethical committees was left to each investigator’s discretion according to local and national regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

De Luca, G., Nardin, M., Algowhary, M. et al. Impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on short-term outcome in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction during COVID-19 pandemic: insights from the international multicenter ISACS-STEMI registry. Respir Res 23, 207 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02128-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-022-02128-0