Abstract

Background

Iron deficiency affects up to 50% of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) but iron markers such as ferritin and serum iron are confounded by several non-disease related factors like acute inflammation and diet. The aim of this study was to identify a new marker for iron deficiency and clinical outcome in PAH patients.

Methods

In this single-center, retrospective study we assessed indicators of iron status and clinical parameters specifying the time to clinical worsening (TTCW) and survival in PAH patients at time of initial diagnosis and at 1-year follow-up using univariable and multivariable analysis.

Results

In total, 150 patients were included with an invasively confirmed PAH and complete data on iron metabolism. The proportion of hypochromic erythrocytes > 2% at initial diagnosis was identified as an independent predictor for a shorter TTCW (p = 0.0001) and worse survival (p = 0.002) at initial diagnosis as well as worse survival (p = 0.016) at 1-year follow-up. Only a subset of these patients (64%) suffered from iron deficiency. Low ferritin or low serum iron neither correlated with TTCW nor survival. Severe hemoglobin deficiency at baseline was significantly associated with a shorter TTCW (p = 0.001).

Conclusions

The presence of hypochromic erythrocytes > 2% was a strong and independent predictor of mortality and shorter TTCW in this cohort of PAH patients. Thus, it can serve as a valuable indicator of iron homeostasis and prognosis even in patients without iron deficiency or anemia. Further studies are needed to confirm the results and to investigate therapeutic implications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In the last decade, increasing attention has been paid to the role of iron metabolism in cardiovascular diseases [1, 2]. Iron deficiency can affect up to 50% of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) [3, 4]. Moreover, iron deficiency in PAH patients correlated with more severe disease, including reduced exercise capacity and worse survival [5,6,7]. While PAH guidelines suggest iron supplementation when needed [8, 9], iron supplementation trials in PAH patients provided inconclusive results in three smaller studies with around 22 PAH patients [6, 10, 11]. Only in two of these three studies the 6-minute walking distance increased significantly in previously iron deficient patients [10, 11]. Nevertheless, all studies presented improvements of study specific measurements such as quality of life [10], exercise endurance time [6] or right ventricular fractional area change [11]. In these studies, the definition of iron deficiency was based on the three parameters each, including serum ferritin, transferrin saturation (TSAT), and serum iron or hemoglobin concentration. Furthermore, treatment of iron deficiency should be managed with extreme caution since underlying conditions, such as infection and inflammation, that alter iron handling, put the patient at risk of having detrimental effects due to iron treatment.

Routinely, iron deficiency diagnosis relies on the TSAT and serum ferritin levels. However, these parameters can be altered by concomitant conditions such as inflammation and infections and, thus, not always accurately reflect the iron status [12]. In addition, the measurement of serum iron levels depends on the daytime and food intake [13]. Thus, these parameters are unreliable if not recorded under standardized conditions such as fasting. Moreover, TSAT is often not part of the routine laboratory assessment. Therefore, readily available, new iron deficiency indices which mirror the clinical status of the patient and which are less affected by inflammation are needed to facilitate therapeutic decisions.

Hypochromic erythrocytes may be such a new “biomarker” because they reflect upon the availability of iron in the previous 120 days and are both an early marker of anemia and an index of response to iron treatment [14]. Hypochromic erythrocytes mirror the current iron availability status in the bone marrow and erythropoietic system since they are produced as a consequence of iron deficient erythropoiesis [14]. Therefore, they are useful indicators of functional iron deficiency, providing values independent of concomitant inflammatory processes [15, 16].

The aim of the current study was to correlate routinely measured iron related parameters including the percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes with clinical data at baseline and during follow-up in particular with time to clinical worsening (TTCW) and survival in a large cohort of PAH patients.

Methods

Study design

This was a single-center, retrospective study analyzing TTCW and survival during yearly follow-up in PAH patients diagnosed and treated in the Centre for Pulmonary Hypertension between 04/2013 and 08/2017 at the Thoraxklinik Heidelberg gGmbH at Heidelberg University Hospital, Germany. This study evaluated data from incident PAH patients with at least one follow-up examination.

TTCW was defined as death, transplantation, hospitalization due to PAH, worsening of World Health Organization (WHO) functional class (FC) of at least one stage or 6-minute walking distance (6MWD) deterioration ≥ 15% compared to baseline. Clinical worsening was recorded either with date and type of worsening or death with date, cause and circumstances. The ethics committee of the Medical Faculty of Heidelberg University Hospital had no objection against the conduct of the study (internal number S-317/2020). The study complied with the Declaration of Helsinki in its current version.

Study population

Inclusion criteria were incident patients aged ≥ 18 years with PAH (defined according to the European Society of Cardiology/European Respiratory Society pulmonary hypertension guidelines) [9] diagnosed by right heart catheterization, defined as a mean pulmonary arterial pressure ≥ 25 mmHg, pulmonary arterial wedge pressure ≤ 15 mmHg and pulmonary vascular resistance > 3 Wood Units. Patients with PAH and comorbidities were defined according to the published criteria from the 6th World Symposium on PH and the Cologne consensus conference [17, 18]. Patients with cardiac phenotype had PAH plus at least three of the following conditions: systemic arterial hypertension under medication, diabetes mellitus, treated for coronary artery disease in stable state disease, atrial fibrillation, enlargement of left atrium or obesity (defined by body mass index > 30 kg/m2). The included patients with pulmonary phenotype had normal or close to normal pulmonary function tests, no significant alterations in lung parenchyma in computed tomography of the lungs but low diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide < 45% of predicted or hypoxemia. Patients with pulmonary hypertension due to significant left heart disease or lung disease as defined by the guidelines were excluded [9] to avoid impact of other factors acting on iron metabolism such as anticoagulation or severe hypoxemia.

Study investigations

The variables to investigate the clinical significance of iron deficiency were derived from routine laboratory assessments (ferritin, serum iron, hemoglobin, mean erythrocyte corpuscular volume, mean corpuscular hemoglobin, mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration, red cell distribution width (RDW) and percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes, which contained less than 28 g/dl hemoglobin). Patients presenting with anemia or low ferritin values were treated with 1000 mg intravenous ferric carboxy-maltose if needed. Clinical parameters for characterization included demographic data, comorbidities, hospitalization data, vital signs, echocardiography, hemodynamics measured by right heart catheterization, spirometry, blood gas analysis, lung function, WHO FC, 6MWD, as well as the laboratory parameters for the assessment of renal function (creatinine, glomerular filtration rate).

Statistical methods

Data including patient characteristics and the clinical parameters were presented using descriptive statistics with mean ± standard deviation and frequency tables. Frequency data, presented as n and %, were analyzed using the chi-square test. Survival was analyzed with Kaplan–Meier statistics and Cox regression analysis. For survival, date of initial diagnosis (i.e. right heart catheterization) was used as baseline and date of death due to any cause, date of lung transplantation or date of last patient contact when the patient was still alive were used for follow-up.

The prognostic value for survival and TTCW at initial diagnosis and survival one year after initial diagnosis were investigated by univariable and multivariable analysis with hemoglobin deficiency, RDW ≥ 15.7%, ferritin < 40 ng/ml, hypochromic erythrocytes > 2% and low iron as outcome variables. Hemoglobin deficiency was defined as < 12 g/dl in women and < 13 g/dl in men and low serum iron as < 12 µmol/l in women and < 13 µmol/l in men. Reference values are based on internal laboratory reference ranges or clinical routine cut-offs for iron supplementation. All variables identified with the univariable log rank tests as being significantly associated with survival (p < 0.05) were further analyzed using a multivariable Cox model.

Clinical characteristics between patient groups with better and worse survival for independent prognostic predictors were compared with Mann–Whitney U-Test. Non-parametric correlations were assessed with Spearmen’s correlation. Correlations of categorical variables were assessed with the Mann–Whitney test. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were performed with IBM SPSS V 25.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Results

Patient characteristics

Among 1522 right heart catheterizations performed at the Center for Pulmonary Hypertension, Thoraxklinik Heidelberg between April 2013 and August 2017, 150 patients had an invasively confirmed PAH diagnosis and a concomitant iron metabolism assessment. Table 1 shows baseline characteristics of the whole study cohort. Out of 150 PAH patients, 93 were female (62%) with a mean age of 63.3 ± 14.5 years. Forty-four patients were included with idiopathic PAH (29%), 4 with heritable PAH (3%), 50 patients with associated PAH (33%) and 52 patients were classified as PAH with comorbidities (35%, 33 cardiac and 19 pulmonary comorbidities). Right heart catheterization revealed severely increased pulmonary pressures with high pulmonary vascular resistances. Patients showed an enlarged right heart with mild impairment of right ventricular systolic function. On average patients displayed a normal renal function. Characteristics at one year follow-up are summarized in Additional file 1: Table S1. WHO FC and 6MWD remained largely unchanged within the first year after diagnosis.

Anemia and iron metabolism

In the study cohort, 10.7% of patients presented with anemia, i.e., hemoglobin deficiency, at diagnosis (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The number of anemic patients almost doubled to 21.1% after 1-year of follow-up. Low serum iron was nearly unchanged between baseline (54.1%) and 1-year follow-up (50.5%). Likewise, hypochromic erythrocytes (33.9% at baseline vs. 36.5% after 1 year) and serum ferritin levels (16.0% at baseline and 15.7% after 1 year) showed similar values over time.

Iron metabolism and anemia in PAH patients at baseline and after 1 year. Within four years, 150 patients were included in the study. The percentage of patients with low hemoglobin doubled within a year, while the levels of low iron, hypochromic erythrocytes and ferritin < 40 ng/ml were comparable at baseline and 1 year follow-up

Since anemia and iron deficiency could also be caused by malignancies and gastrointestinal bleeding, we evaluated our patient cohort in this respect. Overall, a malignancy was reported in 12 patients: 9 have had a tumor before the diagnosis of PAH and were declared ‘tumor free’ at baseline; three developed a tumor after one, two and three years after diagnosis of PAH, respectively. The most frequent malignancies were breast cancer (6 patients), lung cancer (2 patients), other (4 patients). Only two of the patients had anemia at baseline, both had a past history of breast cancer and were tumor-free for ≥ 10 years before PAH diagnosis. Gastrointestinal bleeding occurred in 11 patients during follow-up (earliest after 6 months): in 7 cases due to gastrointestinal ulcers and in 4 cases due to angiodysplasia in the intestine. None of them had anemia at baseline.

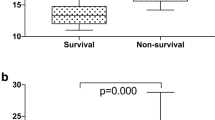

Survival and clinical worsening

To identify parameters associated with TTCW and survival iron related parameters were assessed by Kaplan–Meier analyses (Table 2). Ferritin levels had no prognostic value for survival or TTCW. Hemoglobin deficiency was significantly associated with a shorter TTCW (p = 0.001) (Fig. 2) and showed a trend towards increased mortality in the group of patients with low hemoglobin at diagnosis (p = 0.093) in the univariable analysis. However, no association with survival and hemoglobin levels 1 year after diagnosis could be detected (Fig. 2).

Survival and TTCW according to low hemoglobin levels. Low hemoglobin levels (red) were associated with shorter time to clincial worsening (TTCW, left) and showed a trend to predict survival at baseline (center) but not after 1-year follow-up in the univariable analysis (right). Green lines represent patients with normal hemoglobin (Hg) values, which corresponds to ≥ 12 g/dl in women and ≥ 13 g/dl in men

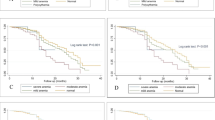

The presence of hypochromic erythrocytes > 2% at baseline resulted in a strong, independent prediction of TTCW (p < 0.0001) and survival (p = 0.001) in the univariable analysis (Fig. 3, Table 2). Likewise, also the presence of hypochromic erythrocytes > 2% detected 1 year after diagnosis was still associated with impaired survival (p = 0.015). Importantly, hypochromic erythrocytes were the only measurement which remained significant for TTCW and survival in the multivariable analysis (Table 3). The distribution of hypochromic erythrocyte levels in our patient cohort can be seen in Fig. 4. When the measure of RDW ≥ 15.7% [19] was added to the analysis hypochromic erythrocytes remained significant for TTCW (p = 0.011) together with low hemoglobin (p = 0.006), for survival at baseline low hemoglobin (p = 0.029) and RDW ≥ 15.7% (p = 0.011) were the strongest predictors, while for survival at one year hypochromic erythrocytes continued to be the only and highly significant predictor (p < 0.001).

Survival and TTCW according to hypochromic erythrocytes rate. Patients with > 2% of hypochromic erythrocytes showed a shorter time to clinical worsening (TTCW, red lines, left) and had a worse prognosis at baseline (center) and after 1 year follow-up (right) in the univariable and mulitvariable analyses. The displayed p-values correspond to the univariable analysis. Green lines represent patients with ≤ 2% hypochromic erythrocytes

Differences between patients with hypochromic erythrocytes ≤ 2% and > 2%

Patients with a higher rate of hypochromic erythrocytes (≤ 2% vs. > 2%), displayed a greater impairment of renal function (glomerular filtration rate 72.8 ± 28.1 vs. 57.4 ± 26.3 ml/min respectively, p = 0.021, Table 3), anemia (19% vs. none), and impairment of lung diffusion capacity (55.7 ± 22.2 vs. 43.4 ± 21.8%, p = 0.022). When renal insufficiency was defined as a glomerular filtration rate < 60 ml/min/1.73 m2 patients with hypochromic erythrocytes > 2% were not overrepresented (16/30 vs. 14/30; chi square test p = 0.06). Similarly, patients with oxygen pressure in capillary blood < 60 mmHg were not overrepresented in the group of patients with hypochromic erythrocytes > 2% (6/10 vs 4/10; chi square test p = n.s.).

No differences were found regarding right heart size or function in transthoracic echocardiography. Hemodynamics were comparable between the two groups except for a slightly higher pulmonary arterial wedge pressure in patients with more hypochromic erythrocytes (9.8 ± 2.2% vs. 11.3 ± 3.1%, p = 0.045). Absolute values of hypochromic erythrocytes showed a weak but significant correlation with right ventricular pump function (p = 0.02, Spearman correlation coefficient = 0.294). Interestingly, there was also a significant correlation between higher hypochromic erythrocytes and worse WHO FC, (Mann–Whitney Test: FC II vs. FC III p = 0.012, FC II vs. FC IV p = 0.001, FC III vs. FC IV p = 0.205). No correlations could be identified for hypochromic erythrocytes and age, gender, mean pulmonary arterial pressure, pulmonary vascular resistance, or right ventricular systolic pressure.

Discussion

This is the first study identifying the biomarker “hypochromic erythrocytes higher than 2%” at baseline as a strong independent predictor for shorter TTCW (p = 0.0001) and worse survival (p = 0.002) in PAH patients. Increased numbers of hypochromic erythrocytes one year after initial diagnosis were also predictive of worse survival (p = 0.016). By contrast, ferritin and low serum iron were not able to predict mortality in PAH patients, although these parameters are commonly used in clinical routine to assess iron metabolism and to indicate iron supplementation therapy. Severe hemoglobin deficiency at baseline was significantly associated with a shorter TTCW (p = 0.001).

Clinical impact of iron deficiency in PAH

Various combinations of iron markers, such as ferritin, TSAT or the soluble transferrin receptor are commonly used to define iron deficiency [20]. According to Sonnweber and colleagues, depending on the definition the prevalence of iron deficiency ranged from 11 to 75% in a cohort of 153 precapillary PH patients [20]. The lowest prevalence was based on the lowest cut-off values of TSAT together with serum ferritin while the highest prevalence resulted from less stringent, but routinely used cut-off values [20]. In the cohort analyzed here, 54% and 16% of PAH patients showed low iron and ferritin levels, respectively. Consistent with previous studies [5, 20] ferritin failed to predict TTCW or mortality in PAH. Overall, 10.7% of patients presented with anemia at diagnosis. The rate of anemic patients almost doubled to 21.1% after 1-year of follow-up, whereas hypochromic erythrocytes (33.9% at baseline vs 36.5% after 1 year) showed similar values over time. We speculate that ferritin, a marker for systemic iron availability, does not correlate with TTCW or mortality due to falsely high serum ferritin levels as result of inflammation and chronic kidney failure [21]. Impaired renal function often occurs in PAH and can increase ferritin levels due to a reduced renal excretion of the iron hormone hepcidin [21]. Hepcidin binds to the iron exporter ferroportin and triggers its degradation. This process significantly contributes to iron deficiency in serum as it diminishes dietary iron absorption and blocks iron release from macrophages that recycle aging red blood cells. As a consequence, ferritin levels rise despite diminished iron availability in the circulation [22]. This can falsely signal a normal iron status in PAH patients with impaired renal function. Furthermore, iron deficiency is involved in a circulus vitiosus in PAH. On one side, the upregulation of hepcidin in PAH leads to iron malabsorption, on the other side iron deficiency may counterfeit hypoxia, promoting pulmonary vasoconstriction leading to deterioration of the disease [23].

Hypochromic erythrocytes as new “biomarker” reflecting iron status

Being less affected by inflammation status [24], hypochromic erythrocytes may provide crucial information for PAH patients since PAH is frequently associated with inflammatory conditions such as systemic sclerosis, HIV and porto-pulmonary hypertension [25]. The percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes has been previously suggested as a reliable marker of iron deficiency in kidney disease patients that is more reliable compared to TSAT and serum ferritin [15, 26]. Winkelmayer et al. showed that a level of hypochromic erythrocyte > 10% was associated with two-fold mortality over long term follow-up among kidney transplanted patients [27]. Increased percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes was strongly associated with iron deficiency, especially among patients with renal insufficiency [28]. Similarly, iron deficiency was associated with worse survival in PAH [12]. Rhodes et al. showed that RDW > 15.7%, an iron-dependent measure, is a prognostic parameter predicting survival in idiopathic PAH [19]. In our analysis with a mixed cohort of PAH patients RDW ≥ 15.7% was an independent predictor for survival at baseline, but not for TTCW or survival after one year. Until our study, the impact of the percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes on prognosis in PAH has not been investigated before. We showed for the first time that increased numbers of hypochromic erythrocytes reliably reflected iron deficiency even in PAH patients with normal ferritin. While only 64% of the patients with > 2% hypochromic erythrocytes showed low ferritin levels and only 19% were diagnosed with anemia, a worse survival could be identified in this cohort. The variability of the definition of iron deficiency in different conditions can lead to controversial indication for iron supplementation [23], depending on functional iron deficiency of each individual patient. Thus, hypochromic erythrocytes could be a reliable parameter of iron homeostasis and outcome even in the absence of anemia. Another advantage of hypochromic erythrocytes as new “biomarker” is its availability in the routine clinical practice.

Hypochromic erythrocytes might therefore be useful as a future therapeutic target in the context of iron supplementation therapy indication, outcome and monitoring.

Limitations

Our study is limited by its retrospective nature. One major limitation was the absence of TSAT and soluble transferrin receptor levels as they were not measured in our patients within the routine work-up and could therefore not be included in the analysis. Moreover, no assessment of patients’ diet and nutrition was performed. Several biomarkers, such as soluble transferrin receptor index, growth differentiation factor-15 as well as inflammatory biomarkers such as interleukin 6 have been previously reported to be associated with the course of PAH [19]. Although the comparison of the new and the previously reported biomarkers would be interesting, it was not possible due to missing data. Moreover, we included no data of a non-disease control group in our analysis which could have characterized the new parameter in greater detail. However, we could analyze a large, clinically well characterized cohort of PAH patients. Currently we are performing a prospective study aimed at better characterizing iron metabolism in PAH patients and its correlation with clinical parameters (NCT04086537).

Conclusions

Hypochromic erythrocytes > 2% independently predicted a reduced TTCW and survival. This new biomarker may be useful to assess the occurrence of functional iron deficiency with greater reliability compared to other routinely used parameters of iron status, such as ferritin, serum iron or hemoglobin. A parameter, which mirrors iron deficiency largely independent of an inflammatory state and shows prognostic capacity for TTCW and survival even in the absence of anemia could become a useful indicator of iron status and a valuable tool for indicating the need of iron supplementation and monitoring supplementation effects. Further studies are needed to confirm the results and to investigate therapeutic implications.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyses from the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- DLCO:

-

Diffusion capacity of carbon monoxide

- FC:

-

Functional class

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- PAH:

-

Pulmonary arterial hypertension

- MCH:

-

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin

- MCHC:

-

Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration

- MCV:

-

Mean corpuscular volume

- n.s.:

-

Not significant

- RDW:

-

Red cell distribution width

- TSAT:

-

Transferrin saturation

- TTCW:

-

Time to clinical worsening

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- 6MWD:

-

6-minute walking distance

References

Chopra VK, Anker SD. Anaemia, iron deficiency and heart failure in 2020: facts and numbers. ESC Heart Fail. 2020;7:2007–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.12797.

Vinchi F, Porto G, Simmelbauer A, et al. Atherosclerosis is aggravated by iron overload and ameliorated by dietary and pharmacological iron restriction. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:2681–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurheartj/ehz112.

Rhodes CJ, Howard L, Busbridge M, et al. Iron deficiency independently predicts survival in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Thorax. 2010;65:33. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.150961.33.

Ruiter G, Lankhorst S, Boonstra A, et al. Iron deficiency is common in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1386–91. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00100510.

Rhodes CJ, Howard LS, Busbridge M, et al. Iron deficiency and raised hepcidin in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: clinical prevalence, outcomes, and mechanistic insights. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:300–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2011.02.057.

Ruiter G, Manders E, Happe CM, et al. Intravenous iron therapy in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension and iron deficiency. Pulm Circ. 2015;5:466–72. https://doi.org/10.1086/682217.

Soon E, Treacy CM, Toshner MR, et al. Unexplained iron deficiency in idiopathic and heritable pulmonary arterial hypertension. Thorax. 2011;66:326–32. https://doi.org/10.1136/thx.2010.147272.

Galiè N, Channick RN, Frantz RP, et al. Risk stratification and medical therapy of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53: 801889. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01889-2018.

Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary hypertension: The Joint Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Respiratory Society (ERS): Endorsed by: Association for European Paediatric and Congenital Cardiology (AEPC), International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation (ISHLT). Eur Respir J. 2015;46:903–75. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01032-2015.

Viethen T, Gerhardt F, Dumitrescu D, et al. Ferric carboxymaltose improves exercise capacity and quality of life in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension and iron deficiency: a pilot study. Int J Cardiol. 2014;175:233–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2014.04.233.

Olsson KM, Fuge J, Brod T, et al. Oral iron supplementation with ferric maltol in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2020;56:2000616. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.00616-2020.

Sonnweber T, Pizzini A, Tancevski I, et al. Anaemia, iron homeostasis and pulmonary hypertension: a review. Intern Emerg Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11739-020-02288-1.

Dale JC, Burritt MF, Zinsmeister AR. Diurnal variation of serum iron, iron-binding capacity, transferrin saturation, and ferritin levels. Am J Clin Pathol. 2002;117:802–8. https://doi.org/10.1309/2YT4-CMP3-KYW7-9RK1.

Goddard AF, James MW, McIntyre AS, et al. Guidelines for the management of iron deficiency anaemia. Gut. 2011;60:1309–16. https://doi.org/10.1136/gut.2010.228874.

Macdougall IC, Cavill I, Hulme B, et al. Detection of functional iron deficiency during erythropoietin treatment: a new approach. BMJ. 1992;304:225–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.304.6821.225.

Navarro JF, Macia ML. Hypochromic red cells as an indicator of iron deficiency. J Rheumatol. 1997;24:804–5.

Olschewski A, Berghausen EM, Eichstaedt CA, et al. Pathobiology, pathology and genetics of pulmonary hypertension: Update from the Cologne Consensus Conference 2018. Int J Cardiol. 2018;272S:4–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcard.2018.09.070.

McLaughlin VV, Vachiery JL, Oudiz RJ, et al. Patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension with and without cardiovascular risk factors: results from the AMBITION trial. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2019;38:1286–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healun.2019.09.010.

Rhodes CJ, Wharton J, Howard LS, et al. Red cell distribution width outperforms other potential circulating biomarkers in predicting survival in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Heart. 2011;97:1054–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/hrt.2011.224857.

Sonnweber T, Nairz M, Theurl I, et al. The crucial impact of iron deficiency definition for the course of precapillary pulmonary hypertension. PLoS ONE. 2018;13: e0203396. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0203396.

Uehata T, Tomosugi N, Shoji T, et al. Serum hepcidin-25 levels and anemia in non-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients: a cross-sectional study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2012;27:1076–83. https://doi.org/10.1093/ndt/gfr431.

Muckenthaler MU, Rivella S, Hentze MW, et al. A red carpet for iron metabolism. Cell. 2017;168:344–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2016.12.034.

Quatredeniers M, Mendes-Ferreira P, Santos-Ribeiro D, et al. Iron deficiency in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a deep dive into the mechanisms. Cells. 2021. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10020477.

Urrechaga E, Borque L, Escanero JF. Percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes as a potential marker of iron availability. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;50:685–7. https://doi.org/10.1515/cclm.2011.837.

Simonneau G, Montani D, Celermajer DS, et al. Haemodynamic definitions and updated clinical classification of pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J. 2019;53:1801913. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01913-2018.

Urrechaga E, Boveda O, Aguayo FJ, et al. Percentage of hypochromic erythrocytes and reticulocyte hemoglobin equivalent predictors of response to intravenous iron in hemodialysis patients. Int J Lab Hematol. 2016;38:360–5. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijlh.12496.

Winkelmayer WC, Lorenz M, Kramar R, et al. Percentage of hypochromic red blood cells is an independent risk factor for mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2004;4:2075–81. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1600-6143.2004.00604.x.

Thomas DW, Hinchliffe RF, Briggs C, et al. Guideline for the laboratory diagnosis of functional iron deficiency. Br J Haematol. 2013;161:639–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjh.12311.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all patients who participated in the study. This work was part of the doctoral thesis of VT.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PX: Substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the work. VT: this is a part of doctorate thesis of VT: Substantial contributions to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the work. NB: Substantial contributions to the conception, acquisition, data analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the work. AMM: Substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data, drafting of the work. CAE: Substantial contributions to the acquisition of data, drafting of the work. AD: Substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data, drafting of the work. BE: Substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data of the work. MS: Substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data of the work. DC: Substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data of the work. AC: Substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data of the work. EB: Substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data of the work. MK: Substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data of the work. EG: Substantial contributions to the conception, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data of the work. MM: Substantial contributions to the conception, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data of the work. CAE: Substantial contributions to the acquisition and interpretation of data, coordination of the work. All authors agree to all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All data were anonymised and the study was approved by the ethics committee of the medical faculty of Heidelberg University Hospital (internal number S-317/2020). The study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki in its current version.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

PX has received personal fees from MSD and OMT outside the submitted work. VT, MK, MS, DC, AC, AD, MM and CAE declare that they have no competing interests related to this study. AMM has received personal fees from Bayer, outside the submitted work. NB received speaker fees from Actelion pharmaceuticals / Janssen Medical, Bayer HealthCare and MSD, outside the submitted work. EG has received grants and personal fees from Actelion, Bayer AG, and MSD; grants from GSK, Novartis, and United Therapeutics; and personal fees from SCOPE, OrPha Swiss GmbH, and Zurich Heart House, outside the submitted work. BE received travel fees, consulting fees, speaking fees, and/or honoraria from Actelion, MSD, Bayer and OMT, outside the submitted work.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Characteristics at one year follow-up of the study cohort.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xanthouli, P., Theobald, V., Benjamin, N. et al. Prognostic impact of hypochromic erythrocytes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. Respir Res 22, 288 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-021-01884-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-021-01884-9