Abstract

Background

The risk of tuberculosis (TB) in patients with impaired kidney function remains unclear by different stages of renal function impairment.

Methods

We retrospectively recruited all patients with kidney function in a tertiary-care referral center from January 2008 to December 2013 and followed them till December 2016. We defined the primary outcome as active TB development and analyzed the impact of kidney function impairment.

Results

During the study period, a total of 289,579 patients were enrolled for analysis, and of them, 1012 patients had active TB events in an average of 4.13 years of follow-up. According to kidney function impairment, the incidence rate of TB was similar in patients with no chronic kidney disease (CKD) or stage 1 and stage 2, and it increased apparently at stage 3a (167.68 per 100,000 person-years) to stage 3b, stage 4 and stage 5 (229.25, 304.95 and 349.29 per 100,000 person-years, respectively). In a Cox proportional hazard regression model, the dose response of TB risk among different stages of kidney function impairment increased significantly from CKD stage 3a to stage 5. Patients with long-term dialysis had a hazard ratio of 2.041 (1.092–3.815, p = 0.0254), which is similar to that of stage 4 CKD but lower than that of stage 5.

Conclusion

In patients with impaired kidney function, the risk of TB increases from CKD stage 3, and in stage 5, the risk is even higher than that of those receiving dialysis. Further strategies of TB control need to consider this high-risk group.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), tuberculosis (TB) remains the most common infectious disease in the world [1]. In 2017, an estimated 10.0 million people had active TB, and 1.3 million TB related deaths were recorded worldwide [2]. In many countries, TB has declined from high incidence (> 100/100000 person-years) to intermediate (30–100/100000) or low incidence (< 30/100000) [3, 4] under the Global Plan To Stop TB 2006–2015 [5]. In the post-2015 era, WHO suggest the END TB strategy and many frameworks towards TB elimination [6], including to optimize current treatment and to screen high-risk groups for latent TB infection (LTBI) treatment [7]. The WHO suggests a focus on high-risk groups in high or upper-middle income countries when the TB incidence becomes less than 100 per 100,000 person-years [8].

Of the high-risk groups, patients with end-stage renal disease need long-term dialysis is highly recommended for LTBI screening [7], but the risk of TB in patients with decreased kidney function, such as chronic kidney disease (CKD) not requiring dialysis, is still unclear. In particular, the burden of CKD is increasing worldwide, so its correlation with infection of TB is increasing in importance [9]. Actually, immune deficiency due to decline in kidney function is a risk factor for infection [10] and has reportedly been correlated with infection associated mortality [11, 12]. Due to changes in the immune system due to deterioration of kidney function, active TB is an infectious complication that may develop or reactivate from LTBI.

In fact, few studies have examined TB risk in patients with kidney function impairment [13]. Only a previous cohort study reports that an adjusted hazard ratio of pulmonary TB was 1.45-fold higher in the CKD group than the non-CKD group [14]. But there is no study shows the TB risk according to the different stages of kidney function impairment [13], therefore, we cannot pick out which sub-population with kidney function impairment for implementation of LTBI strategy. Hence, we conducted this retrospective cohort study to analyze the correlation between kidney function and the incidence of TB in Taiwan, an intermediate TB country with incidence of 38.9 per 100,000 person-years in 2018 [15], using a large hospital-based cohort.

Methods

Participant enrollment

This retrospective study was conducted in a tertiary-care referral center in northern Taiwan under the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital (NO. 201510009RINB). From January 2008 to December 2013, patients aged ≥20 years were identified. We included patients with data of serum creatinine and excluded those having follow-up periods at the study hospital of less than 6 months and 3 months, respectively, before and after the index data of initial kidney function. In addition, we excluded those who had active tuberculosis before recruitment and within 3 months right after the index data of the kidney function.

Definitions of kidney function, active tuberculosis and co-morbidity

We retrieved the participants’ clinical information such as age, gender, body mass index, and underlying disease from the hospital’s electronic record database within a total 12 months (6 months before and after the index date). We used an abbreviated Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) equation to estimate the glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) [16] and classified the patient’s initial kidney function according to the guidelines of the National Kidney Foundation [17]. The eGFR of ≥90, < 90~ ≥ 60, < 60~ ≥ 45, < 45~ ≥ 30, < 30~ ≥ 15, and < 15 ml/min/1.73m2 stood for no CKD or stage 1, stage 2, stage 3a, stage 3b, stage 4, and stage 5, respectively. We defined active TB by positive culture result for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. For the diagnosis without microbiological evidence, we could define active TB by the unique diagnosis code in electronic chart record, because active TB is a certifiable infectious disease that needs to report to the Taiwan Centers for Disease Control. We used one time of admission diagnosis, or at least two outpatient clinic diagnoses plus prescription of anti-tuberculous agents for TB diagnosis. Co-morbidity of long-term dialysis, transplantation, pneumoconiosis, idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, cirrhosis of the liver, cancer, lupus erythematous, rheumatoid arthritis, polymyositis, and dermatomyositis were defined by a record of a catastrophic illness card. Other underlying diseases were categorized by one admission diagnosis or more than 2 outpatient clinic diagnoses.

Outcome and statistical analysis

We followed up all enrolled participants till December 2016 and defined occurrence of active TB as the primary outcome. The incidence of TB was calculated as the average number per 100,000 person-years. Inter-group differences were compared using t test or one-way ANOVA for continuous variables, where appropriate, and chi squared test for categorical variables. We used Cox proportional hazard regression for time to TB event analysis. Once the patients with CKD at the initial received long-term dialysis or kidney transplantation in the follow-up or were lost to follow-up, they were censored in the time dependent analysis. We combined no CKD or stage 1 and stage 2 as a reference group (≥ 60 min/ml per 1.73m2) in Cox regression analysis because their TB incidence were similar [18]. We calculated the correlations between the kidney function of eGFR and the univariate hazard ratio for TB by Spline Cox proportional regression. We investigated the risk factors for active TB using multivariate Cox proportional hazard regression analysis with possible associated variables from univariate analysis. Only variables with a two-sided p < 0.05 were retained in the final model. All analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographics of patients with different stages of kidney function impairment

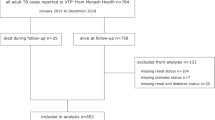

During the study period, a total of 485,190 patients in the study hospital were eligible, and 289,579 were enrolled for analysis after excluding 124,274 for short follow-up (< 90 days), 69,912 for short previous data (< 6 months) and 1425 for having TB within 90 days (Fig. 1). Among them, 1012 patients had development of active TB events during the overall follow up of 1,196,206 person-years, that was averagely 4.13 years/person. Among those with different stages of kidney function impairment (Table 1), old age and male predominance were generally found for those with advanced CKD stages. The mean age of all participants was 5.18 years old (SD: 17.3). The mean age was 43.8 (15.2) in no CKD or stage 1, 55.5 (15.7) in stage 2, 69.5 (12.4) in stage 3a, 71.6 (12.8) in stage 3b, 70.1 (14.2) in stage 4, 62.7 (15.7) in stage 5, 56.9 (14.4) in dialysis, and 54.8 (11.7) in transplant group (p < 0.0001, Table 1). Male gender was around 45.3% in all participants and distributed as 39.7, 49.4, 51.9, 50.3, 50.4, and 52.2% from no CKD or stage 1, stage 2, 3a, 3b, 4 and 5, respectively. Many underlying comorbidities significantly increased in advanced CKD stage included CHF, stroke, DM and SLE. By contrast, obesity was less frequently in in patients with worse kidney function than those with no CKD or stage 1 and 2.

In comparison with patients without TB (Additional file 1: Table S1), those who developed TB during follow-up were older and predominantly male. In addition, they had lower eGFR and more advanced renal disease, dialysis, and kidney transplant. The proportion of patients with active TB development was lower in no CKD or stage 1 and 2, but it became higher in advanced CKD stage 3 to 5 in comparing with those without TB (p < 0.0001). The underlying diseases of pulmonary disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, cancer, heart failure, cirrhosis, diabetes mellitus and autoimmune disease were higher in patients with TB development. By contrast, obesity was higher in patients without TB development.

TB incidence for different kidney functions

According to kidney function, the incidence rate of TB was similar in no CKD or stage 1 and stage 2 (70.06 and 71.08 per 100,000 person-years, respectively), and increased apparently from stage 3a (167.68 per 100,000 person-years, Hazard ratio [HR]: 2.404 [1.956–2.956], p < 0.0001) to stage 3b, stage 4 and stage 5 (incidence: 229.25, 304.95 and 349.29 per 100,000 person-years, and HR: 3.273 [2.509–4.270], 4.317 [3.078–6.054], and 4.852 [3.154–7.646], respectively) (Table 2). Those with long-term dialysis or kidney transplant before case enrollment had TB incidences of 175.60 and 1429.33 per 100,000 person-years, respectively and HR of 2.493 [1.330–4.673] and 20.575 [5.147–82.239], respectively.

For confirming that the case exclusion criteria of follow-up period ≤90 days did not influence the results of TB incidence, we used different follow-up period as exclusion criteria, including ≤30 days or ≤ 180 days and analyzed the TB incidence by different kidney function status. We found that the trends of TB incidence in the different CKD subgroups were similar (Additional file 1: Table S2 and S3).

Risk factors and the hazard ratio for TB development

In a Cox proportional hazard regression model (Table 3), we analyzed the hazard ratio (HR) of TB development for kidney function and other clinically relevant factors. In univariate analysis, patients had similar TB risk in no CKD or stages 1 vs stage 2 (HR: 1.024 [95% C.I.: 0.888–1.182], p = 0.7408, compared with no CKD or stage 1), so we used them as the reference group for those with deteriorated kidney function in Cox regression analysis. In univariate analysis, the dose response of TB risk among different kidney functions increased significantly from CKD stage 3a to stage 5. When we evaluated the univariate HR of TB risk at every eGFR below 90 ml/min/1.73m2 using spline Cox regression, the correlation actually increased slowly in stage 2 and obviously from stage 3a. A plateau was noticed around the beginning of stage 3b and a mild decline at late stage 5. However, the outcome number was small in stage 5, and the 95% confidence interval became large (Fig. 2).

In multivariate Cox regression (Table 3), we adjusted all factors found to be significant in the univariate analysis, and the final model showed that old age (HR: 4.439 [3.539–5.583] for age > 65 years old; HR: 2.040 [1.592–2.614] for age 55–65 years old; HR: 1.392 [1.079–2.797] for age 40–55 years old, compared with age < 40 years old), male (HR: 2.558 [1.977–2.578], and poor kidney function since CKD stage 3b were correlated with higher TB risk. In patients with deteriorated kidney function, the risk of TB development increased significantly from CKD stage 3b to stage 5, similarly to the results of univariate analysis but with the risk adjusted downward. The HR of CKD stage 3a was 1.215 (95% C.I.: 0.995–1.484, p = 0.0563), HR: 1.538 in stage 3b ([1.182–2.002], p = 0.0014), 2.065 in stage 4 ([1.473–2.894]), and 2.877 in stage 5 ([1.872–4.421]) in comparison with stages 1 and 2. The risk in patients with long-term dialysis was HR of 2.041 (1.092–3.815, p = 0.0254), which is similar to that of stage 4 CKD. The HR was 15.269 in those with kidney transplant, and it was much higher than those of other subgroups. The proportion of ever corticosteroid use (n = 24 [63.2%] vs n = 87,922 [30.4%], p < 0.001) and immune-suppressants use (n = 21 [55.3%] vs n = 2239 [0.8%], p < 0.001) during the follow up were higher in patients receiving kidney transplant than other patients. In addition, the underlying diseases of COPD, bronchiectasis, pneumoconiosis, cancer, congestive heart failure, diabetes mellitus, SLE and RA were independent conditions for favoring TB development. Among them, pneumoconiosis (HR: 10.149), SLE (HR: 6.323), bronchiectasis (HR: 2.959), RA (HR: 2.305), and cancer (HR: 2.006) were the most important (HR >2.0) clinical diseases predisposing TB development.

Discussion

In the present study, patients with decline in kidney function of CKD stage 3 and worse had increasing incidences and HR for TB development. The incidence and HR of TB in CKD stage 5 seemed around two-fold and 1.4-fold, respectively, relative to those with long-term dialysis although the 95% C.I.s were overlapped. Decline in kidney function is assumed to influence immune function [10] and is associated with oxidative stress and inflammation due to the decrease of renal clearance of toxins [13]. In addition, Vitamin D insufficiency is not uncommon among patients with CKD or dialysis and might lead to immune dysfunction [19]. Many immune cells such as T cells and B cells, as well as natural killer cells, will be attenuated when renal function has deteriorated [20,21,22]. Previously, many studies focus on the TB risk in dialysis population [23, 24], but few studies report increasing TB incidence in patients with CKD [14, 25]. Cheng et al. reported the adjusted HR of pulmonary TB was 1.45-fold higher in the CKD group than in the non-CKD group. The effect of TB susceptibility due to differences in kidney function has scarcely been reported before [13]. Cho et al. analyzed a community-based cohort and showed that stage 1–4 CKD had a 25% increase in TB hazard than those without CKD [25]. The present study was conducted based on a large hospital cohort and report the association between TB risk and different stages of impaired kidney function.

The incidence and HR of developing active TB rise significantly from CKD stage 3 to stage 5. This finding is compatible with a previous assumption [13] that the decline of immunity begins and wastes accumulate significantly in stage 3 CKD. The risk of TB worsens in advanced stages of CKD and is highest at CKD stage 5 (incidence of 349.29 per 100,000 person-years), where it is around 7.0-fold that of the 55–65 year-old general population [26]. But the rate of increase in the adjusted HR begins to slow from stage 4 to stage 5. However, the unadjusted HR within stage 5 slightly declines as eGFR decreases (Fig. 2).

For patients receiving long-term dialysis, the TB incidence is similar to that of patients with CKD stage 3, and the adjusted HR resembles that of patients with stage 4 CKD (175.6 per 100,000 person-years; adjusted HR: 2.041). The possible explanation is that the dialysis remove partial uremic toxin and might decrease the uremia related immune suppression [27]. Therefore, the TB risk of advanced CKD might be much higher than that of our previous consideration. Because the WHO suggests active LTBI screening in patients with dialysis, those with stage 3 CKD or higher should also be targeted for TB prevention [6, 8]. Such screening needs to be incorporated into a CKD care bundle to counter their higher infection risk. On the other hand, patients with kidney transplants still have very high risk of TB development. The incidence of 1429.33 per 100,000 person-years is around 48-fold that of the same-aged general population [26]. This result is much higher than those in a previous report [28] and might have been influenced by the small case number in this cohort. It might also be due to the higher proportion of corticosteroid and immune-suppressants use that may be correlated with increasing TB incidence [29]. However, the influences by corticosteroid and immunosuppressants need to be analyzed in further study specially designed for drug dose, duration and equivalent effect.

In addition to the stage of kidney impairment, TB development was also significantly associated with old age, male gender, and underlying co-morbidities such as underlying airway and immunocompromised diseases in the multivariate Cox regression analysis. They are all well known risk factors for TB [30,31,32,33] and might play a role in developing TB. In the future, we might integrate the risk factors to validate this model and form a prediction score model.

There are several limitations in this study. First, this was a hospital-based study design. Although we only enrolled patients who were regularly followed up at the study hospital, there was a risk of outcome underestimation bias. In addition, the retrospective design might have missed some data in the record review, such as TB contact history and BCG vaccination. Third, because the study hospital is a tertiary referral center, selection bias existed and TB incidence as well as underlying co-morbidities might have been higher than those in the general population.

Conclusions

Patients with impaired kidney function, eGFR ≤60 ml/min/1.73m2, had increasing risk for TB development. The risk reached 2.877-fold and 2.041-fold HR of TB risk in patients with stage 5 CKD and in those with long-term dialysis, respectively, in comparison with those with CKD ≤ stages 2. The results indicate that patients with advanced CKD are susceptible to TB and have a higher risk than patients receiving dialysis. In the development of LTBI prevention strategies for patients with long-term dialysis, those with advanced CKD should also be considered.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- CKD:

-

Chronic kidney disease

- eGFR:

-

Estimated glomerular filtration rate

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- LTBI:

-

Latent tuberculosis infection

- MDRD:

-

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

World Health Organization. Group at risk: WHO report on the tuberculosis epidemic. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1996.

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2018. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018.

Organization WH: Global Tuberculosis Report. 2015.

Cheng MP, Abou Chakra CN, Yansouni CP, Cnossen S, Shrier I, Menzies D, Greenaway C. Risk of active tuberculosis in patients with Cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:635–44.

Wejse C. Tuberculosis elimination in the post millennium development goals era. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;32:152–5.

Lonnroth K, Migliori GB, Abubakar I, D'Ambrosio L, de Vries G, Diel R, Douglas P, Falzon D, Gaudreau MA, Goletti D, et al. Towards tuberculosis elimination: an action framework for low-incidence countries. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:928–52.

Rose DN. Benefits of screening for latent mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:1513–21.

Getahun H, Matteelli A, Abubakar I, Aziz MA, Baddeley A, Barreira D, Den Boon S, Borroto Gutierrez SM, Bruchfeld J, Burhan E, et al. Management of latent mycobacterium tuberculosis infection: WHO guidelines for low tuberculosis burden countries. Eur Respir J. 2015;46:1563–76.

Jha V, Garcia-Garcia G, Iseki K, Li Z, Naicker S, Plattner B, Saran R, Wang AY, Yang CW. Chronic kidney disease: global dimension and perspectives. Lancet. 2013;382:260–72.

Carrero JJ, Stenvinkel P. Inflammation in end-stage renal disease--what have we learned in 10 years? Semin Dial. 2010;23:498–509.

Maizel J, Deransy R, Dehedin B, Secq E, Zogheib E, Lewandowski E, Tribouilloy C, Massy ZA, Choukroun G, Slama M. Impact of non-dialysis chronic kidney disease on survival in patients with septic shock. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:77.

Fried LF, Katz R, Sarnak MJ, Shlipak MG, Chaves PH, Jenny NS, Stehman-Breen C, Gillen D, Bleyer AJ, Hirsch C, et al. Kidney function as a predictor of noncardiovascular mortality. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:3728–35.

Romanowski K, Clark EG, Levin A, Cook VJ, Johnston JC. Tuberculosis and chronic kidney disease: an emerging global syndemic. Kidney Int. 2016;90:34–40.

Cheng KC, Liao KF, Lin CL, Liu CS, Lai SW. Chronic kidney disease correlates with increased risk of pulmonary tuberculosis before initiating renal replacement therapy: a cohort study in Taiwan. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e12550.

Centers of Disease Control DoH, R.O.C. (Taiwan). CDC annual report 2019. Taipei: Centers of Disease Control, Department of Health, R.O.C. (Taiwan); 2019.

Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function--measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:2473–83.

National Kidney F. K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;39:S1–266.

Webster AC, Nagler EV, Morton RL, Masson P. Chronic Kidney disease. Lancet. 2017;389:1238–52.

Jean G, Souberbielle JC, Chazot C. Vitamin D in chronic Kidney disease and Dialysis patients. Nutrients. 2017;9:1.

Peraldi MN, Berrou J, Metivier F, Toubert A. Natural killer cell dysfunction in uremia: the role of oxidative stress and the effects of dialysis. Blood Purif. 2013;35(Suppl 2):14–9.

Litjens NH, van Druningen CJ, Betjes MG. Progressive loss of renal function is associated with activation and depletion of naive T lymphocytes. Clin Immunol. 2006;118:83–91.

Anding K, Gross P, Rost JM, Allgaier D, Jacobs E. The influence of uraemia and haemodialysis on neutrophil phagocytosis and antimicrobial killing. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:2067–73.

Shu CC, Hsu CL, Wei YF, Lee CY, Liou HH, Wu VC, Yang FJ, Lin HH, Wang JY, Chen JS, et al. Risk of tuberculosis among patients on Dialysis: the predictive value of serial interferon-gamma release assay. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e3813.

Li SY, Chen TJ, Chung KW, Tsai LW, Yang WC, Chen JY, Chen TW. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection of end-stage renal disease patients in Taiwan: a nationwide longitudinal study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:1646–52.

Cho PJ, Wu CY, Johnston J, Wu MY, Shu CC, Lin HH. Progression of chronic kidney disease and the risk of tuberculosis: an observational cohort study. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2019;23:555–62.

Control TCoD: Taiwan tuberculosis control report 2017. 2017.

Hauser AB, Stinghen AE, Kato S, Bucharles S, Aita C, Yuzawa Y, Pecoits-Filho R. Characteristics and causes of immune dysfunction related to uremia and dialysis. Perit Dial Int. 2008;28(Suppl 3):S183–7.

Liu J, Yan J, Wan Q, Ye Q, Huang Y. The risk factors for tuberculosis in liver or kidney transplant recipients. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:387.

Singh N, Paterson DL. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in solid-organ transplant recipients: impact and implications for management. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:1266–77.

Gao L, Li X, Liu J, Wang X, Lu W, Bai L, Xin H, Zhang H, Li H, Zhang Z, et al. Incidence of active tuberculosis in individuals with latent tuberculosis infection in rural China: follow-up results of a population-based, multicentre, prospective cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017;17:1053–61.

Shu CC, Wu HD, Yu MC, Wang JT, Lee CH, Wang HC, Wang JY, Lee LN, Yu CJ, Yang PC. Taiwan anti-mycobacteria investigation G: use of high-dose inhaled corticosteroids is associated with pulmonary tuberculosis in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Medicine (Baltimore). 2010;89:53–61.

Yang Y, Thumboo J, Tan BH, Tan TT, Fong CHJ, Ng HS, Fong KY. The risk of tuberculosis in SLE patients from an Asian tertiary hospital. Rheumatol Int. 2017;37:1027–33.

Handa R, Upadhyaya S, Kapoor S, Jois R, Pandey BD, Bhatnagar AK, Khanna A, Goyal V, Kumar K. Tuberculosis and biologics in rheumatology: a special situation. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20:1313–25.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Yu-Ting Wang, Department of Medical Research, National Taiwan University Hospital, for their support with data and statistics.

Funding

The study was supported in part by grants from the Centers for Disease Control, Taiwan (MOHW-107-CDC-C-114-000104) and National Taiwan University Hospital (NTUH-109-S4552). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SCC and CCY designed and coordinated the study. Post-doctor fellow YYC, Drs SCC, WPW, WYF, CCY, CSL, WJY, LHH and YJY were involved in data interpretation, analysis, revision, critique and preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Research Ethics Committee of National Taiwan University Hospital approved this study (IRB No.: 201510009RINB).

Consent for publication

Not applicable. The present study did not contain any individual person’s data in any form.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1 Table S1.

Demographics of study population according to development of tuberculosis (TB). Table S2. Incidence rates of tuberculosis (TB) if we excluded patients lost to follow up < 30 days. Table S3. Incidence rates of tuberculosis (TB) if we excluded patients lost to follow up < 180 days.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Shu, CC., Wei, YF., Yeh, YC. et al. The impact on incident tuberculosis by kidney function impairment status: analysis of severity relationship. Respir Res 21, 51 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-020-1294-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-020-1294-5