Abstract

Background

This study investigated the function of SMAD3 (SMAD family member 3) in regulating PAX6 (paired box 6) in non-small cell lung cancer.

Methods

First, qRT-PCR was employed to detect SMAD3 expression in cancer tissues along with normal tissues and four cell lines, including BEAS-2B, H125, HCC827 and A549 cells. SMAD3 was knocked down by small interference RNA (siRNA), and then its expression was determined via qRT-PCR and Western blot analysis. The correlation between SMAD3 and PAX6 was determined by double luciferase reporter experiments and chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay. Cell viability was evaluated by CCK-8 and colony forming assays, while cell migration and invasion were detected by Transwell analysis.

Results

SMAD3 and PAX6 were upregulated in lung cancer tissues and cancer cells. Knocking down SMAD3 and PAX6 by transfection with siRNAs specifically suppressed the expression of SMAD3 and PAX6 mRNA and protein levels. SMAD3 could promote PAX6 transcriptional activity by binding to its promoter. Reduced expression of SMAD3 led to the downregulation of PAX6 mRNA and protein levels along with decreased cell migration, invasion, proliferation and viability in A549 and HCC827 cells. PAX6 overexpression altered the si-SMAD3-induced inhibition of cell migration, invasion, proliferation and viability in A549 and HCC827 cells. Additionally, PAX6 knockdown alone also repressed the cell migration, invasion, proliferation and viability of the cell lines.

Conclusions

SMAD3 promotes the progression of non-small cell lung cancer by upregulating PAX6 expression.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

One of the most common cancers is non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), which accounts for 1/4 cancer-related mortalities each year [1]. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors and surgical resection are common treatments for patients with NSCLC, but, in the virtue of drug resistance or compromising cardiopulmonary reserves, the effects of treatment are poor [2, 3]. Furthermore, a novel method for treating lung cancer, stereotactic body radiation therapy, could shorten the treatment course due to high doses of radiation and precise targeting [4]. Although many advances in cancer research have been made, the prognosis of NSCLC is still unsatisfactory, with a lower 5-year survival rate compared with other cancers [5]. Consequently, investigating the pathogenesis of NSCLC might give us a chance to discover impactful and effective treatment methods for NSCLC, and has grown in importance.

Previous investigations have showed that members of the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) superfamily and their associated downstream signaling components, SMADs, play a crucial role in several aspects of breast cancer onset and disease progression [6]. The role of Smad3 in many cancers is an emerging area of intense research. According to a former study, SMAD3 might contribute to increasing the risk of breast cancer by encoding a key protein that interacts with BRCA2 [7]. Moreover, Li et al. reported that the deregulation of SMAD3 expression was associated with ventricular septal defects [8]. Meanwhile, some studies have focused on uncovering the correlation between SMAD3 and lung cancer. For example, Samanta et al. reported that reducing SMAD3 expression could abrogate TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition, resulting in promoting tumorigenicity [9]. Previous studies have shown that SMAD3 is involved in aggressive tumor behavior in NSCLC and might act as a potential target for the treatment of the cancer [10]. A published paper reported that downregulating TGFBR2 expression promoted the proliferation, migration and invasion of NSCLC cells by reducing the activation and phosphorylation of Smad2 and Smad3 [11]. Thus, the elusive mechanisms involving SMAD3 in the development and progression of NSCLC deserve more attention.

Paired box (PAX) proteins play a crucial role in normal embryogenesis, which can regulate cell proliferation, self-renewal and apoptosis and even participate in the migration of embryonic precursor cells as well as differentiation programs [12]. There is an emerging hypothesis that PAX proteins might inhibit terminal differentiation and apoptosis in issue-specific stem cells, resulting in maintaining these cells [13]. This effect is likely to be involved in cancer cell development and progression. Moreover, PAX6, a paired box family gene, was recently demonstrated to be involved in the development of pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors [14]. Furthermore, in the investigation by Li et al., PAX6 expression had been proven to be suppressed by microRNA-7 in human colorectal cancer cells, resulting in inhibited cell proliferation and invasion [15]. Similarly, Luo et al. had suggested that miR-7 negatively regulates PAX6 protein levels, which can promote the proliferation and invasion of NSCLC cells via activation of the ERK and MAPK signaling pathways [16]. Kiselev et al. also showed that the transcription factor PAX6 was a novel prognostic factor and putative tumor suppressor in non-small cell lung cancer [17]. Pax6 also interacts with the Smad3 MH1 domain, and Pax6/Smad3 interactions appear to be necessary for TGF-β signaling [18]. Tripathi et al. also indicated the involvement of SPARC in the Smad3-dependent autoregulation of Pax6 to complete the loop and interact with Smad3 [19]. However, deeper investigation and discussion on SMAD3 and PAX6 in NSCLC cells is still needed.

In this study, we investigated the function of SMAD3 in non-small cell lung cancer using cell proliferation and migration experiments and explored the relationship between SMAD3 and PAX6 with double luciferase reporter experiments and chromatin immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP).

Methods

Clinical tissue samples

The 20 NSCLC tissue samples and 20 normal tissues examined in the experiments were provided by Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University & Beijing Tuberculosis and Thoracic Tumor Research Institute. Histopathological types were assigned using WHO pathological staging criteria. The 20 tumor tissues used in our study were adenocarcinomas. Frozen tissue was used in our study. All patients investigated were not treated with preoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy. The Ethics Committee of Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University & Beijing Tuberculosis and Thoracic Tumor Research Institute and the patients have approved the experiments in the present study.

Cell cultures

The normal human lung epithelial cells, BEAS-2B, and cancer cell lines, H125, HCC827 and A549, were obtained from the BeNa Culture Collection (Beijing, China). BEAS-2B and A549 cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM)/F12 containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 10 g/ml streptomycin. The H125 and HCC827 cell lines were both incubated in RPMI1640 medium containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum, 100 IU/ml penicillin, and 10 g/ml streptomycin. All cell lines were incubated in a 95% air and 5% carbon dioxide (CO2) atmosphere at 37 °C.

Western blot analysis

Approximately 1 × 107 cells were solubilized in lysis buffer purchased from the Beyotime Institute of Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Twelve percent SDS-PAGE was utilized to separate the proteins. Afterwards, approximately 60 μg of protein was transferred to a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane. Then, the membrane adsorbing the proteins was incubated with TBST buffer (Tween 20) at room temperature containing 5% nonfat milk. After 3 h, the membrane was incubated with primary antibodies for 3 h at room temperature. After washing with TBST buffer (Tween 20), the membranes were treated with a matched secondary antibody for 1 h. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit anti-SMAD3 (1:5000 dilution, ab40854) and rabbit anti-PAX6 (1:1000 dilution, ab5790); the secondary antibody was goat anti-rabbit labeled with HRP (horseradish peroxidase) (1:5000 dilution, ab205718). All antibodies were obtained from Abcam (Cambridge, MA, USA). An ECL kit and the Image-Pro plus software, version 6.0, from Media Cybernetics (Rockville, MD, USA) were used to determine the chemiluminescent and relative protein expression, respectively, which was represented as the density ratio vs. GAPDH.

Cell transfection

To knock down SMAD3 and PAX6, Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was used to transfect A549 and H125 cells with siRNA-SMAD3. Two different SMAD3-specific siRNAs (GenePharma, Shanghai, China), si-SMAD3 #1 and si-SMAD3 #2, and a PAX6 siRNA, si-PAX6 (GenePharma, Shanghai, China), were transfected into the cells to knockdown gene expression. Si-NC, a scrambled siRNA, was used as a control. The pcDNA3.1-PAX6 (p-PAX6) and pcDNA3.1 (GenePharma, Shanghai, China) control vectors were also transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The siRNA sequences are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Double luciferase reporter assay

The PAX6 promoter region was cloned into the PGL3-luc luciferase reporter vector to construct the PAX6-luc luciferase reporter vector. To investigate the relationship between SMAD3 and PAX6, pCMV-SMAD3 was cotransfected with the PAX6-luc reporter plasmid and pRL-TK plasmid as an internal control using Lipofectamine™ 2000. Luciferase activities were detected 48 h after transfection with the Dual-luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega, WI, USA). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase activity. The primers for plasmid construction are shown in Additional file 2: Table S2.

Real-time RT-PCR

The RNeasy® Mini Kit (Qiagen®, Venlo, Netherlands) was performed to extract total RNA from collected tissues or cultured cells, which was then reverse transcribed into cDNA using the M-MLV reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen). SYBR Premix Ex Taq from TaKaRa Biotechnology (Tokyo, Japan) was used to quantify SMAD3 and PAX6 expression. GUSB and GAPDH were both used as internal controls for the tissues and cells, respectively. The primer probes were purchased from GenePharma (Shanghai, China). All data were quantified with the 2−ΔΔCT method. The qPCR primers are shown in Additional file 2: Table S2.

ChIP assay

One percent formaldehyde was used to treat and crosslink cells from each group for approximately 10 min at room temperature. After lysis, the cells were sonicated to breakdown the chromatin into 200 bp to 1 kb fragments. Antibodies specific to SMAD3 (ab28379) or IgG (ab172730), as a negative control (Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), were used to immunoprecipitate the chromatin by generating antigen-antibody complexes. Afterwards, the complexes were collected by protein A agarose beads (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), followed by washing to remove any nonspecific binding. The DNA was eluted from the immunoprecipitated complexes on the agarose beads with 0.1 M NaHCO3 and 1% SDS. The primers for ChIP-qPCR are shown in Additional file 2: Table S2.

CCK-8 assay

The Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay was used to evaluate cell viability and proliferation. Briefly, the cell lines were seeded onto 96-well plates (3000 cells/well, Corning, NY, USA) and incubated for the indicated time points (0, 24, 48, 72, or 96 h). Next, 10 μL of CCK-8 solution was added to each well and the cells were incubated in the dark at 37 °C for 2 h. Afterwards, the absorbance was detected at 490 nm to assess cell viability.

Transwell migration assay

In total, 1 × 105 cells in 250 μL of medium containing 0.1% FBS were seeded into 24-well-plates (Corning, NY, USA) with noncoated inserts for the migration assay. Then, 750 μL medium supplemented with 10% FBS was added into the lower chamber. After incubating the cells for 24 h, nonmigrating cells in the upper chamber were washed away and the cells in the lower chamber were fixed with cold methanol. Hoechst 33258 and a Zeiss Axiophot epifluorescence microscope purchased from QImaging (Surrey, BC) were used to stain and count cells in 5 random visible fields, respectively.

Transwell invasion assay

Serum-free medium was added to dilute the Matrigel (1:7), and then 50 μL of diluted Matrigel was inoculated into each chamber. The prepared chambers were placed in an incubator at 37 °C for 4 h for the following experiments. In total, 1 × 105 cells in 250 μL of medium containing 0.1% FBS were seeded into the apical chamber covered by diluted Matrigel, while 500 μL of culture medium with 10% FBS was added to the basolateral chamber. After incubating for 36 h, the nonmigrating cells in the upper chamber were washed away and the cells in the lower chamber were fixed with cold methanol. Hoechst 33258 and a Zeiss Axiophot epifluorescence microscope purchased from QImaging (Surrey, BC) were used to stain and count cells in 5 random visible fields, respectively.

Colony forming assay

After trypsinization, single-cell suspensions were collected followed by seeding of approximately 300 cells/well into 6-well-plates (Corning, NY, USA). All plates were cultured to form visible colonies at 37 °C. Afterwards, the cells in the plates were fixed with methanol and counted using 0.5% crystal violet.

Statistical analysis

All measurements were performed in triplicate. The Student’s t-test was employed to analyze the differences between two groups with P < 0.05 considered to be significant. The differences among the groups of samples were accomplished by one-way ANOVA. Data are presented as the mean ± SD.

Results

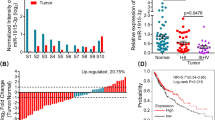

The high expression of SMAD3 and PAX6 in NSCLC tissues and cells

QRT-PCR was utilized to investigate SMAD3 and PAX6 expression levels in 20 normal and 20 NSCLC cancer tissues. Figure 1a and e suggest that SMAD3 and PAX6 are up-regulated in NSCLC tissues compared with normal tissues (P < 0.01). Similar SMAD3 and PAX6 mRNA and protein expression was observed in the four cell lines, including the normal BEAS-2B human lung epithelial cells and H125, HCC827 and A549 cancer cell lines. Figure 1b and f demonstrated that SMAD3 and PAX6 mRNA levels were upregulated in cancer cell lines compared with the normal cell line (P < 0.01). Furthermore, higher SMAD3 and PAX6 protein expression was observed in the cancer cell lines compared with the healthy human lung epithelial cells (Fig. 1c, d, g, h, Additional file 3: Figure S1a and b) (P < 0.01). Thus, NSCLC tissues and cells displayed high SMAD3 and PAX6 expression compared with control tissues and cells.

SMAD3 and PAX6 are highly expressed in NSCLC tissues and cells. a SMAD3 expression levels in NSCLC tissues compared with the normal groups (n = 20). b SMAD3 mRNA levels in the BEAS-2B, H125, HCC827 and A549 cell lines normalized to GAPDH (left panel) and GUSB (right panel) (n = 3). (c and d) SMAD3 protein levels in the BEAS-2B, H125, HCC827 and A549 cell lines (n = 3). e PAX6 expression levels in the NSCLC tissues compared with the normal groups (n = 20). f PAX6 mRNA levels in the BEAS-2B, H125, HCC827 and A549 cell lines normalized to GAPDH (left panel) and GUSB (right panel)(n = 3). g and h PAX6 protein levels in the BEAS-2B, H125, HCC827 and A549 cell lines (n = 3). Data represent the mean ± SD. **P < 0.01 compared with the control group

Knocking down SMAD3 lowered PAX6 expression

To investigate the effect of SMAD3 on PAX6 expression, SMAD3 was knocked down by siRNA transfection, followed by the detection of PAX6 and SMAD3 expression levels by qRT-PCR and Western blot in the A549 and HCC827 cell lines. The results demonstrated that silencing SMAD3 downregulated PAX6, as shown by the lower PAX6 and SMAD3 mRNAs and proteins in the si-SMAD3#1 and si-SMAD3#1 groups compared with the NC group in the A549 (Fig. 2a, b and Additional file 3: Figure S1c, all P < 0.05) and HCC827 (Fig. 2c, d and Additional file 3: Figure S1d) cell lines.

SMAD3 knockdown decreased SMAD3 and PAX6 expression levels. a SMAD3 and PAX6 mRNA expression levels in A549 cells transfected with siRNA and normalized to GAPDH (left panel) and GUSB (right panel). b SMAD3 and PAX6 protein expression levels in A549 cells transfected with siRNA (n = 3). c SMAD3 and PAX6 mRNA expression levels in HCC827 cells transfected with siRNA normalized to GAPDH (left panel) and GUSB (right panel). d SMAD3 and PAX6 protein expression levels in HCC827 cells transfected with siRNA. Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with the control group

The SMAD3 protein regulated PAX6 transcription via binding its promoter

Dual luciferase assay and ChIP assay were exploited to assess the effects of SMAD3 on PAX6 promoter activity. Sequence analysis revealed 3 putative SMAD3 binding sites in the PAX6 promoter. Serial deletion showed that the second and third SMAD3 binding sites were critical for SMAD3-induced PAX6 trans-activation in A549 and HCC827 cells (Fig. 3a and c). ChIP assay further confirmed that SMAD3 directly binds to the PAX6 promoter in A549 and HCC827 cells (Fig. 3b and d). These studies demonstrated that PAX6 was a direct transcriptional target of SMAD3 in both cell lines.

SMAD3 knockdown inhibited PAX6 transcription in A549 and HCC827 cells. a Deletion mutation analyses identified the FoxC1-responsive regions in the CCL2 promoter in A549 cells. Serially truncated PAX6 promoter constructs were cotransfected with pCMV-SMAD3 and relative luciferase activities were determined. The schematic constructs are shown (left) and the bar graphs represent the relative levels of luciferase activity in each of the samples (right). #P < 0.05 compared with the pCMV group. *P < 0.05 compared with the group with the − 1978 ~ + 50 regions cloned into the luciferase reports plasmids. b ChIP assay demonstrated the direct binding of SMAD3 to the PAX6 promoter in A549 cells. Real-time PCR was performed to detect the amounts of immunoprecipitated products. The cells were crosslinked and the chromatin was immunoprecipitated using anti-SMAD3 or control antibodies. #P < 0.05 compared with the pCMV group. *P < 0.05 compared with the distant region. c Deletion mutation analyses identified FoxC1-responsive regions in the CCL2 promoter in HCC827 cells. #P < 0.05 compared with the pCMV group. *P < 0.05 compared with the group with the − 1978 ~ + 50 regions cloned into the luciferase reports plasmids. d ChIP assay demonstrated the direct binding of SMAD3 to the PAX6 promoter in HCC827 cells. #P < 0.05 compared with the pCMV group. *P < 0.05 compared with the distant region

SMAD3 downregulation on the physiological abilities of A549 and HCC827 cells

To evaluate A549 and HCC827 cell proliferation, invasion and migration after SMAD3 silencing and explore whether SMAD3 exerts its biological activity through PAX6, we performed CCK-8, colony forming and Transwell assays. Figure 4a and b demonstrated that the A549 cell line si-SMAD3#1 group showed lower cell migration (Fig. 4a) and invasion (Fig. 4b) compared with the control group (P < 0.01). Moreover, when cells in the si-SMAD3#1 group were cotransfected with pc-DNA3.1-PAX6 (si-SMAD3 + p-PAX6), cell migration and invasion were up-regulated compared with the si-SMAD3#1 group (P < 0.01), which suggests that PAX6 overexpression could reverse the cellular physiological abilities inhibited by SMAD3 knockdown. Similar results were observed in the HCC827 cell line, which are shown in Fig. 4c and d. Similarly, the si-SMAD3#1 group cells showed lower colony formation abilities compared with control group in both the A549 and HCC827 cell lines (Figs. 5a and b), and upregulating PAX6 expression improved this situation (P < 0.01). The CCK-8 assay showed that downregulation of SMAD3 suppressed cell viability compared with control group and that enhanced PAX6 expression improved the inhibition of si-SMAD3 on cell viability in A549 and HCC827 cells (Figs. 5c and d, P < 0.05). These results demonstrated that the downregulation of SMAD3 acted as an inhibitor of A549 and HCC827 cell physiological abilities, which could be partially reversed by PAX6 overexpression.

SMAD3 downregulation decreased the cell migration and invasion of A549 and HCC827 cells. a SMAD3 downregulation inhibited the migration of A549 cells. b SMAD3 downregulation inhibited the invasion capacity of A549 cells. c SMAD3 downregulation inhibited the migration of HCC827 cells. d SMAD3 downregulation inhibited the invasion capacity of HCC827 cells. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data represent the mean ± SD. NC group: cells were transfected with scrambled siRNA. **P < 0.01 compared with the NC group. #P < 0.05 compared with the si-SMAD3 #1 group

SMAD3 downregulation decreased the colony forming capacity and cell viability of A549 and HCC827 cells. a The colony forming capacity of A549 cells was detected by colony forming assay. b The cell viability of A549 cells was determined by CCK-8 assay. c The colony forming capacity of HCC827 cells was detected by colony forming assay. d The cell viability of HCC827 cells was determined by CCK-8 assay. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with the NC group. #P < 0.05 compared with the si-SMAD3 group

SMAD3 and PAX6 knockdown to explore their relevance in the A549 and HCC827 cell lines

To further explore the relevance and functional effects of PAX6, we depleted PAX6 and SMAD3 through the transfection of si-SMAD3 and si-PAX6, respectively (Figs. 6 and 7). We demonstrated that A549 cell migration (Fig. 6a), invasion (Fig. 6b), colony forming ability (Fig. 7a) and cell viability (Fig. 7b) were repressed in the si-PAX6 group, which show lower decreasing trends compared with the si-SMAD3 group, though there were no significant differences. Similar experiments were also performed in the HCC827 cell line (Figs. 6c and d and 7c and d). PAX6 showed similar functions as SMAD3, but the tendency might be weaker. Thus, SMAD3 might partially target PAX6 to regulate cell migration, invasion, proliferation and viability in NSCLC patients with positive correlations.

PAX6 downregulation decreased the cell migration and invasion of A549 and HCC827 cells. a PAX6 downregulation inhibited the migration of A549 cells. b PAX6 downregulation inhibited the invasion capacity of A549 cells. c PAX6 downregulation inhibited the migration of HCC827 cells. d PAX6 downregulation inhibited the invasion capacity of HCC827 cells. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data represent the mean ± SD. **P < 0.01 compared with the NC group

PAX6 downregulation decreased the colony forming capacity and cell viability of A549 and HCC827 cells. a The colony forming capacity of A549 cells after transfection with si-SMAD3 or si-PAX6 was detected by colony forming assay. b The cell viability of A549 cells after transfection with si-SMAD3 or si-PAX6 was determined by CCK-8 assay. c The colony forming capacity in HCC827 cells after transfection with si-SMAD3 or si-PAX6 was detected by colony forming assay. d The cell viability of HCC827 cells after transfection with si-SMAD3 or si-PAX6 was determined by CCK-8 assay. All experiments were performed in triplicate. Data represent the mean ± SD. *P < 0.05 and **P < 0.01 compared with the NC group

Discussion

In the present study, SMAD3 expression levels were evaluated in healthy and NSCLC tissues and cells, showing its high expression. This high SMAD3 expression might play a crucial role in the development of NSCLC through the targeted modulation of PAX6 expression, resulting in the enhancement of cell migration, invasion, proliferation and viability.

In a previous study, SMAD3 was significantly associated with human osteoarthritis and upregulated in human osteoarthritic cartilage, though not due to DNA methylation in the promoter region [20, 21]. Qian et al. showed that enhancing SMAD3 phosphorylation was associated with high metastatic potential in nonsmall cell lung cancer by downregulating E-cadherin [22]. Furthermore, Yang et al. demonstrated that inhibiting SMAD-dependent signaling in NSCLC might repress the epithelial-mesenchymal transition and cell invasion [23]. However, SMAD3 is also likely to play a role as a cancer suppressor in NSCLC through other mechanisms. For example, in the study by Samanta et al., smoking promotes tumorigenicity and results from the reduction in SMAD3 expression along with the abrogation of TGF-β-mediated growth inhibition [9]. It was also shown that NORAD (also known as LINC00657 or LOC647979), a cytoplasmic long noncoding RNA, indirectly interacts between importin β1 and SMAD3 in NSCLC, and is widely considered as a regulator of TGF-β signaling [10]. Therefore, the function of SMAD3 in NSCLC might have a dual character, which deserves deeper investigation. In our study, high SMAD3 expression was found in NSCLC cells and tissues and acts as an oncogene.

Understanding on the effects of deregulated PAX6 expression on the development of NSCLC remains insufficient, and few studies have focused on the relationship between SMAD3 and PAX6. In accordance with the study by Zhao et al., PAX6 expression was significantly enhanced in NSCLC tissues compared with matched adjacent tissues and was associated with promoting cell cycle progression [24]. Moreover, Zhang et al. demonstrated that PAX6 gene methylation in NSCLC is usually associated with poor prognosis in NSCLC via a methylation-specific PCR assay [25]. Therefore, there is research that strongly supports the assumption that PAX6 is a valid and positive prognostic marker in node-positive NSCLC patients.

The relevance between SMAD3 and PAX6 has been explored. It was shown that SMAD3 interacted with PAX6 and repressed autoregulation of the PAX6 P1 promoter in NSCLC cells. Therefore, in the present study, SMAD3 and PAX6 and their interactions were deeply investigated; we found that SMAD3 expression positively promoted PAX6 transcription, which then regulated NSCLC cell migration, proliferation and viability. However, as the transfection efficiency and quantitative examination were different, comparing the effects between knocking down SMAD3 and PAX6 might make little sense, although we did find that si-SMAD3 was more effective at affecting cell migration, invasion, colony formation and proliferation than si-PAX6.

Generally, NSCLC tissues and cell lines had higher SMAD3 and PAX6 expression level than normal tissues and cell lines. Moreover, SMAD3 downregulation could inhibit PAX6 transcription, resulting in the suppression of PAX6 expression and hindering cell migration, invasion, proliferation and viability in NSCLC cells. Based on these findings, inhibiting SMAD3 and PAX6 should be further explored and may become a promising mechanism for treating nonsmall cell lung cancer in the future.

Conclusions

SMAD3 and PAX6 were upregulated in lung cancer tissues and cancer cells. Knocking down SMAD3 and PAX6 by transfection with specific siRNAs suppressed the expression of SMAD3 and PAX6 mRNA and protein levels. SMAD3 could promote PAX6 transcriptional activity via binding to its promoter. Reduced expression of SMAD3 downregulated PAX6 at the mRNA and protein levels while also decreasing cell migration, invasion, proliferation and viability in NSCLC cells. PAX6 overexpression altered the inhibitory effects of si-SMAD3 on cell migration, invasion, proliferation and viability. PAX6 knockdown alone could also inhibit A549 and HCC827 cell functions. Thus, SMAD3 promotes the progression of nonsmall cell lung cancer by upregulating PAX6 expression.

References

Iyengar P, Kavanagh BD, Wardak Z, Smith I, Ahn C, Gerber DE, Dowell J, Hughes R, Abdulrahman R, Camidge DR, Gaspar LE, Doebele RC, Bunn PA, Choy H, Timmerman R. Phase II trial of stereotactic body radiation therapy combined with erlotinib for patients with limited but progressive metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3824–30.

Zhang Y, Yao K, Shi C, Jiang Y, Liu K, Zhao S, Chen H, Reddy K, Zhang C, Chang X, Ryu J, Bode AM, Dong Z, Dong Z. 244-MPT overcomes gefitinib resistance in non-small cell lung cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2015;6:44274–88.

Donington J, Ferguson M, Mazzone P, Handy J, Jr SM, Fernando H, Loo B, Jr LM, de Hoyos A, Detterbeck F, Pennathur A, Howington J, Landreneau R, Silvestri G. Thoracic Oncology Network of the American College of Chest P, the Workforce on Evidence-Based Surgery of the Society of Thoracic S: American College of Chest Physicians and Society of Thoracic Surgeons consensus statement for evaluation and management for high-risk patients with stage I non-small cell lung cancer. Chest. 2012;142:1620–35.

Shi S, Zeng Z, Ye L, Huang Y, He J. Risk factors associated with symptomatic radiation pneumonitis after stereotactic body radiation therapy for stage I non-small cell lung Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat. 2017;16:316–20.

Tanoue LT, Tanner NT, Gould MK, Silvestri GA. Lung cancer screening. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015;191:19–33.

Liu Y, Chen X, Xue X, Shen C, Shi C, Dong J, Zhang H, Liang R, Li S, Xu J. Effects of Smad3 on the proliferation and steroidogenesis in human ovarian luteinized granulosa cells. IUBMB Life. 2014;66:424–37.

Walker LC, Fredericksen ZS, Wang X, Tarrell R, Pankratz VS, Lindor NM, Beesley J, Healey S, kConFab CX, Stoppa-Lyonnet D, Tirapo C, Giraud S, Mazoyer S, Muller D, Fricker JP, Delnatte C, Collaborators GS, Schmutzler RK, Wappenschmidt B, Engel C, Schonbuchner I, Deissler H, Meindl A, Hogervorst FB, Verheus M, Hooning MJ, van den Ouweland AM, Nelen MR, Ausems MG, et al. evidence for SMAD3 as a modifier of breast cancer risk in BRCA2 mutation carriers. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12:R102.

Li FF, Zhou J, Zhao DD, Yan P, Li X, Han Y, Li XS, Wang GY, Yu KJ, Liu SL. Characterization of SMAD3 gene variants for possible roles in ventricular septal defects and other congenital heart diseases. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0131542.

Samanta D, Gonzalez AL, Nagathihalli N, Ye F, Carbone DP, Datta PK. Smoking attenuates transforming growth factor-beta-mediated tumor suppression function through downregulation of Smad3 in lung cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila). 2012;5:453–63.

Kawasaki N, Miwa T, Hokari S, Sakurai T, Ohmori K, Miyauchi K, Miyazono K, Koinuma D. Long noncoding RNA NORAD regulates transforming growth factor-beta signaling and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-like phenotype. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:2211–20.

Li G, Wu F, Yang H, Deng X, Yuan Y. MiR-9-5p promotes cell growth and metastasis in non-small cell lung cancer through the repression of TGFBR2. Biomed Pharmacother. 2017;96:1170–8.

Shaham O, Menuchin Y, Farhy C, Ashery-Padan R. Pax6: a multi-level regulator of ocular development. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2012;31:351–76.

Bai SW, Li B, Zhang H, Jonas JB, Zhao BW, Shen L, Wang YC. Pax6 regulates proliferation and apoptosis of human retinoblastoma cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52:4560–70.

Lai JP, Mertens RB, Mirocha J, Koo J, Venturina M, Chung F, Mendez AB, Kahn M, Dhall D. Comparison of PAX6 and PAX8 as immunohistochemical markers for pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Endocr Pathol. 2015;26:54–62.

Li Y, Li Y, Liu Y, Xie P, Li F, Li G. PAX6, a novel target of microRNA-7, promotes cellular proliferation and invasion in human colorectal cancer cells. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:598–606.

Luo J, Li H, Zhang C. MicroRNA-7 inhibits the malignant phenotypes of nonsmall cell lung cancer in vitro by targeting Pax6. Mol Med Rep. 2015;12:5443–8.

Kiselev Y, Andersen S, Johannessen C, Fjukstad B, Standahl Olsen K, Stenvold H, Al-Saad S, Donnem T, Richardsen E, Bremnes RM, Rasmussen Busund LT. Transcription factor PAX6 as a novel prognostic factor and putative tumour suppressor in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2018;8:5059.

Grocott T, Frost V, Maillard M, Johansen T, Wheeler GN, Dawes LJ, Wormstone IM, Chantry A. The MH1 domain of Smad3 interacts with Pax6 and represses autoregulation of the Pax6 P1 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:890–901.

Tripathi R, Mishra R. Interaction of Pax6 with SPARC and p53 in brain of mice indicates Smad3 dependent auto-regulation. J Mol Neurosci. 2010;41:397–403.

Aref-Eshghi E, Liu M, Razavi-Lopez SB, Hirasawa K, Harper PE, Martin G, Furey A, Green R, Sun G, Rahman P, Zhai G. SMAD3 is upregulated in human osteoarthritic cartilage independent of the promoter DNA methylation. J Rheumatol. 2016;43:388–94.

Aref-Eshghi E, Zhang Y, Hart D, Valdes AM, Furey A, Martin G, Sun G, Rahman P, Arden N, Spector TD, Zhai G. SMAD3 is associated with the total burden of radiographic osteoarthritis: the Chingford study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97786.

Qian Q, Shi X, Lei Z, Zhan L, Liu RY, Zhao J, Yang B, Liu Z, Zhang HT. Methylated +58CpG site decreases DCN mRNA expression and enhances TGF-beta/Smad signaling in NSCLC cells with high metastatic potential. Int J Oncol. 2014;44:874–82.

Yang H, Zhan L, Yang T, Wang L, Li C, Zhao J, Lei Z, Li X, Zhang HT. Ski prevents TGF-beta-induced EMT and cell invasion by repressing SMAD-dependent signaling in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncol Rep. 2015;34:87–94.

Zhao X, Yue W, Zhang L, Ma L, Jia W, Qian Z, Zhang C, Wang Y. Downregulation of PAX6 by shRNA inhibits proliferation and cell cycle progression of human non-small cell lung cancer cell lines. PLoS One. 2014;9:e85738.

Zhang X, Yang X, Wang J, Liang T, Gu Y, Yang D. Down-regulation of PAX6 by promoter methylation is associated with poor prognosis in non small cell lung cancer. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2015;8:11452–7.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

This study was supported by The Capital Health Research and Development of Special (2016–4-2161).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Contributing to the conception and design: Qiankun Zhang, Ying Hu, Tongmei Zhang, Jie Li, Wenyun Jia, Aimin Hu; Analyzing and interpreting data: Zhe Qian, Zan Li, Hua Zheng, Yuan Gao; Drafting the article: Zhe Qian, Qiankun Zhang; Revising it critically for important intellectual content: Baolan Li, Jiqing Hao; Approving the final version to be published: All authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of Beijing Chest Hospital, Capital Medical University & Beijing Tuberculosis and Thoracic Tumor Research Institute and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and later versions. Informed consent to be included in the study, or the equivalent, was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. siRNAs sequences. (DOCX 15 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Primer sequences used in the study. (DOCX 18 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Qian, Z., Zhang, Q., Hu, Y. et al. Investigating the mechanism by which SMAD3 induces PAX6 transcription to promote the development of non-small cell lung cancer. Respir Res 19, 262 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0948-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-018-0948-z