Abstract

Background

Beta-blockers are commonly prescribed for patients with cardiovascular disease. Providers have been wary of treating chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) patients with beta-blockers due to concern for bronchospasm, but retrospective studies have shown that cardio-selective beta-blockers are safe in COPD and possibly beneficial. However, these benefits may reflect symptom improvements due to the cardiac effects of the medication. The purpose of this study is to evaluate associations between beta-blocker use and both exacerbation rates and longitudinal measures of lung function in two well-characterized COPD cohorts.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 1219 participants with over 180 days of follow up from the STATCOPE trial, which excluded most cardiac comorbidities, and from the placebo arm of the MACRO trial. Primary endpoints were exacerbation rates per person-year and change in spirometry over time in association with beta blocker use.

Results

Overall 13.9% (170/1219) of participants reported taking beta-blockers at enrollment. We found no statistically significant differences in exacerbation rates with respect to beta-blocker use regardless of the prevalence of cardiac comorbidities. In the MACRO cohort, patients taking beta-blockers had an exacerbation rate of 1.72/person-year versus a rate of 1.71/person-year in patients not taking beta-blockers. In the STATCOPE cohort, patients taking beta-blockers had an exacerbation rate of 1.14/person-year. Patients without beta-blockers had an exacerbation rate of 1.34/person-year. We found no detrimental effect of beta blockers with respect to change in lung function over time.

Conclusion

We found no evidence that beta-blocker use was unsafe or associated with worse pulmonary outcomes in study participants with moderate to severe COPD.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) is a progressive and debilitating disease that burdens the healthcare system with frequent office visits and hospitalizations. In recent years, studies have examined both traditional treatments for COPD (long acting beta agonists, long acting muscarinic antagonists, and inhaled corticosteroids) [1, 2] as well as drugs usually reserved for cardiovascular disease or infection (statins and azithromycin) [3, 4] with respect to their efficacy in reducing acute exacerbations of COPD (AECOPD).

Beta-blockers are regularly prescribed in patients with cardiovascular disease, a common comorbidity in patients with COPD. Providers have historically been reluctant to treat COPD patients with beta-blockers due to a concern for precipitating bronchospasm. These concerns have been expressed in review articles and practice guidelines that cited case studies of acute bronchospasm in patients treated with non-selective beta blockers [5, 6]. Cardioselective beta-blockers (or beta-1-blockers) have a 20 fold greater affinity for β-1 receptors and less theoretical risk for bronchoconstriction. Within the last decade, studies have highlighted concern for the use of beta-blockers in patients with COPD [6, 7]; however, Cochrane Reviews in 2005 and 2010 concluded that cardioselective beta blocker use in patients with COPD had no significant adverse effects on FEV1, respiratory symptoms, or responsiveness to beta-agonist inhaled therapy. Sub-group analysis extended this to patients with severe obstruction as well as those with bronchodilator reversibility demonstrated on spirometry [8].

Multiple retrospective studies have suggested that beta-blockers may reduce the mortality of patients with COPD as well as the risk of AECOPD [9, 10]. Mortality as an endpoint in studies linking COPD and beta-blockers is confounded by difficulty determining whether the benefit of the drug is related to its effects on the lung or on coexistent cardiovascular disease [11, 12]. Examining the relationship between beta-blocker use, serial spirometry and rates of AECOPD may provide a more useful depiction of the effect of these medications on lung disease.

The COPD Clinical Research Network has conducted several randomized, placebo-controlled prospective trials in study participants with COPD assessing rates of AECOPD.

The STATCOPE study showed no benefit attributable to daily simvastatin, whereas the

MACRO trial demonstrated reduced rates of AECOPD with azithromycin treatment [3, 4]. The STATCOPE cohort and the placebo arm of MACRO provide a unique opportunity to analyze the effect of beta-blockers on AECOPD in a group of COPD patients with a fairly high prevalence of cardiovascular comorbidities (MACRO) as compared with a group in which cardiovascular comorbidities were mostly excluded (STATCOPE). Given that beta-blockers are likely to have a greater impact on patients with cardiovascular disease, we hypothesized that beta-blockers would associate with lower rates of COPD exacerbation in the MACRO cohort when compared to the STATCOPE cohort due to a higher burden of underlying cardiovascular comorbidity. That is to say, a population with a higher prevalence of cardiac comorbidities may have a greater symptomatic benefit from treatment with beta-blockers when compared with a population with little or no cardiac comorbid disease.

Methods

Patient population

We performed a retrospective review of 1219 study participants who had at least 180 days of follow up from the STATCOPE trial or the placebo arm of the MACRO trial. Entry criteria for the MACRO trial included having a ratio of forced expiratory volume in one second to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) < 70% and being at high risk for experiencing an AECOPD as a result of using supplemental oxygen, or being treated with oral glucocorticoids, antibiotics or being hospitalized in the previous year for an AECOPD. Patients also had no exacerbation within 4 weeks of enrollment 4. Patients in the azithromycin treatment arm of the MACRO study were excluded due to the significant treatment effect of azithromycin on reducing exacerbation rate. The STATCOPE trial had similar inclusion criteria, but excluded patients who were taking a statin, had contraindication to the use of statins or who were found to have an indication for statin therapy [3]. In both the MACRO and STATCOPE studies exacerbations were defined as “a complex of respiratory symptoms (increased or new onset) of more than one of the following: cough, sputum, wheezing, dyspnea, or chest tightness with a duration of at least 3 days requiring treatment with antibiotics or systemic steroids.”

Spirometry

Spirometry was obtained at enrollment and at completion of the study. Each cohort’s spirometric data were analyzed for significant changes over time. The MACRO cohort had spirometry performed at enrollment then at either 6 or 12 months. The STATCOPE cohort had spirometry at enrollment then at 12 or 24 months.

Statistics

The primary study endpoint was rate of acute exacerbation of COPD in each of the four study groups; MACRO on beta-blocker, MACRO off beta-blocker, STATCOPE on beta-blocker and STATCOPE off beta-blocker. COPD exacerbation rates were compared with the use of an event rate ratio; i.e., the number of exacerbations per patient year. Additionally, changes in spirometric data were analyzed over time for each of the four study groups. P-values for mean rate of decline were computed by t-test. Exacerbation rates were compared among the groups using SAS data analysis software.

Results

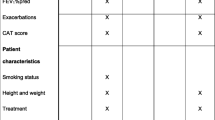

Of the 1219 participants included in our study, 170 (13.9%) reported taking beta-blockers at enrollment. In the STATCOPE cohort 63 of 688 (9.2%) participants were taking beta-blockers along with 107 of 531 (20.2%) in the MACRO placebo arm. The majority of participants in the study had severe or very severe airflow obstruction classified as GOLD stage III or IV. Those taking beta-blockers tended to have a slightly higher FEV1, however we found no statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to demographic characteristics, smoking history or spirometric data (Table 1). As expected, the patients in STATCOPE had a significantly decreased rate of cardiac comorbidities as compared with the MACRO cohort (Table 2). Given the disparity in cardiac comorbidities, the vast majority of patients on beta-blockers in the STATCOPE cohort appeared to be taking the medication for hypertension rather than coronary artery disease (CAD) or a history of myocardial infarction (MI); whereas, a significant percentage in the MACRO cohort was taking the medication for CAD or MI (Table 2).

Patients in the STATCOPE cohort taking beta-blockers had the lowest rate of AECOPD (1.14/person-year, 95% CI = 0.81–1.46), followed by patients in STATCOPE not taking beta-blockers (1.34/person-year, 95% CI = 1.22–1.46). In the MACRO cohort the rate of AECOPD was higher when compared with STATCOPE, but nearly identical with respect to beta-blocker usage within the cohort (Table 3). We found no statistically significant difference between patients taking beta-blockers and the corresponding cohort off beta-blockers.

Percent of subjects free of exacerbation over time is depicted in Fig. 1. In both the MACRO and STATCOPE cohorts, the patients taking beta-blockers had a higher percentage of patients free of exacerbation though this difference did not reach statistical significance in either group. Of note, there was no patient dropout during this period as all patients had at least 180 days of follow up.

Additionally, we studied the change in spirometric data over time for all patients (1063/1219, 87.2%) who had follow-up spirometry. The data shows that the presence of beta-blocker medications had no clinically or statistically significant effect on the change in airflow limitation in this cohort.

Discussion

We found no harmful effect of beta-blockers with respect to change in FEV1 over time and no statistically significant difference in the rate of acute exacerbation of COPD in an at-risk population, regardless of the presence of cardiac comorbidity.

Other retrospective studies have shown beta-blockers to be beneficial in patients with COPD but those observations may represent cardiovascular benefits of beta-blockers rather than pulmonary specific improvements in COPD symptoms or severity.

One recent Swedish nationwide observational study concluded that patients with COPD discharged on a beta-blocker after an MI had a lower all-cause mortality compared with those not discharged on a beta-blocker [13]. However, a large retrospective study showed that patients with severe COPD or asthma had no mortality benefit from taking beta-blockers after MI [14]. Mortality has been shown to be improved in COPD patients specifically taking beta-blockers as monotherapy for hypertension [15]. The reduced prevalence of cardiac comorbidity in the STATCOPE cohort provided an opportunity to compare the effectiveness of beta-blockers in a COPD population with (MACRO) and without (STATCOPE) self-reported cardiac disease. We found no significant difference in rates of AECOPD with respect to beta-blocker use in the cohort with increased cardiac comorbidities. However, there was a slightly lower rate of AECOPD in the patients taking beta-blockers in the STATCOPE cohort and the percent free of exacerbation at 90 and 180 days was higher in patients taking beta-blockers in each cohort. Our inability to detect a statistically significant difference between patients with versus without cardiac disease may be a result of the relatively low number of patients who were taking beta-blockers and reported cardiac comorbidities. Importantly, we did find that COPD patients taking beta-blocker medications did no worse with respect to exacerbation or change in spirometry over a relatively long follow up period when compared with patients who were not taking beta-blockers (Table 4). In accordance with prior studies [13,14,15,16], this finding provides further proof that beta-blockers are safe to use in COPD patients.

Proposed mechanisms by which beta-blockers may have an effect on the COPD process and potentially decrease exacerbation frequency include reduction of ischemic burden and tempering the sympathetic nervous system. COPD has been associated with systemic inflammation, and it has been proposed that the negative effects of neurohumoral activation (such as inflammation, cachexia) can contribute to the cycle of COPD exacerbation and pathophysiology. Beta blockade theoretically could have an impact on neuro-humoral activation and COPD. [17] In addition, animal models have shown that beta-blockers given chronically can increase the density of beta-receptors and reduce airway responsiveness in mice with asthma [18]. Those on beta-blockers may have had more effective blood pressure control and a reduction in complications of less optimally treated diastolic dysfunction which has been linked to the development of acute exacerbations [19].

Other observational studies have shown conflicting results. For instance, Bhatt and colleagues evaluated a cohort of over 3000 patients from the COPDGene cohort and found that patients taking beta-blockers had a decreased incidence on AECOPD. This association held true for severe exacerbations as well as mild to moderate exacerbations [20]. Short et.al. performed a retrospective review of COPD patients on and off beta-blockers and showed that patients taking beta-blockers had lower rates of AECOPD and mortality regardless of the inhaled pulmonary medication regimen in each group [21]. However, in both of these trials, patients had less severe airflow obstruction in comparison to our population (Table 5). Our inability to find a significant effect of beta-blockers may be secondary to the severity of COPD in this cohort. These patients were enrolled due to an increased risk for COPD exacerbation and had relatively severe obstruction on spirometry. This high burden of respiratory disease may overshadow the relatively lesser burden of cardiovascular disease in this population. We also found a high prevalence of chronic bronchitis in each cohort, which was not reported in the other studies, but may have influenced the rate of exacerbation and limited the efficacy of beta-blocker therapy.

Additionally, the expected outcome of beta-blockers having a greater effect on the cohort with cardiac comorbidity (MACRO) may not have been present due to baseline differences in the two groups. The MACRO cohort on beta-blockers trended to be an older population, with an increased number of pack-years which may be reflective of a sicker patient population when compared with the STATCOPE cohort on beta-blockers (Table 1).

Study limitations

The relatively low number of patients taking beta-blockers at enrollment in these studies limited our ability to show a statistically significant difference between the groups with respect to demographic and baseline spirometry (Table 1). Medications and comorbidities were self-reported by the patients at enrollment. Information regarding dosage and specific type of beta-blocker (i.e. beta-1 selective or nonselective) medication was not available. Though there is inherent weakness in the design of all retrospective analyses, the data presented are derived from well-constructed, prospective, large multicenter trials. Despite the limitations, our study is the first to compare the efficacy of beta-blockers in a COPD population with higher versus lower prevalence of cardiac comorbidities.

Conclusion

We found no evidence that beta-blockers significantly affected the rate of AECOPD regardless of whether the patients did or did not report cardiac comorbidities. We did find that beta-blockers had no detrimental effect on lung function in a population that was at increased risk for AECOPD. Because previous observational studies have reported conflicting data, the question will require a large, prospective and randomized trial to determine the benefits of beta-blocker therapy in COPD patients.

References

Tashkin DP, Celli B, Senn S, Burkhart D, Kesten S, Menjoge S, Decramer M. A 4 years trial of tiotropium in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1543–54.

Calverly PMA, Anderson JA, Celli B, et al. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Eng J Med. 2007;356:775–89.

Criner GJ, Connett JE, Aaron SD, et al. Simvastatin for the prevention of exacerbations in moderate-to-severe COPD. N Eng J Med. 2014;370:2201–10.

Albert RK, Connett J, Bailey WC, et al. Azithromycin for prevention of exacerbations of COPD. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:689–98.

JNC VI. The sixth report of the joint national committee on prevention, detection, evaluation, and treatment of high blood pressure. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:2413–46.

van der Woude HJ, Zaagsma J, Postma DS, et al. Detrimental effects of beta-blockers in COPD: a concern for nonselective beta-blockers. Chest. 2005;127:818–24.

Egred M, Shaw S, Mohammad B, et al. Under-use of beta-blockers in patients with ischaemic heart disease and concomitant chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. QJ Med. 2005;98:493–7.

Salpeter SR, Ormiston TM, Salpeter EE. Cardioselective beta-blockers in patients with reactive airway disease: a meta analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;19:CD003566.

Etminan M, Jafari S, Carleton B, Fitzgerald John M. Beta blocker use and COPD mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2012;12:48.

Du Q, Sun Y, Ding N, Lu L, Chen Y. Beta-blockers reduced the risk of mortality and exacerbation in patients with COPD: a meta-analysis of observational studies. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113048.

Rutten FH, Zuithoff NP, Hak E, Grobbee DE, Hoes AW. Beta-blockers may reduce mortality and risk of exacerbations in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:880–7.

Kubota Y, Asai K, Furuse E, Nakamura S, Murai K, Tsukada YT, Shimizu W. Impact of β-blocker selectivity on long-term outcomes in congestive heart failure patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2015;10:515–23. doi:10.2147/COPD.S79942. eCollection 2015.

Andell P, Erlinge D, Smith JG, Sundstrom J, Lindahl B, James S, Koul S. Beta blocker use and mortality in COPD patients after myocardial infarction: a Swedish nationwide observational study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(4). pii: e001611. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001611.

Chen J, Radford MJ, Wang Y, Marciniak TA, Krumholz HM. Effectiveness of Beta-Blocker Therapy After Acute Myocardial Infarction in Elderly Patients With Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease or Asthma. JACC. 2001;Vol. 37,No. 7.

Au DH, Bryson CL, Fan VS, Udris EM, Curtis JR, McDonell MB, Fihn SD. Beta-blockers as single-agent therapy for hypertension and the risk of mortality among patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Med. 2004;117:925–31.

van Gestel YRBM, Hoeks SE, Sin DD, et al. Impact of cardioselective b-blockers on mortality in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atherosclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:695–700.

Andreas S, Anker SD, Scanlon PD, Somers VK. Neurohumoral activation as a link to systemic manifestations of chronic lung disease. Chest. 2005;128(5):3618–24.

Callaerts-Vegh Z, Evans KL, Dudekula N, et al. Effects of acute and chronic administration of beta-adrenoceptor ligands on airway function in a murine model of asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4948–53.

Abusiad GH, Barbagelata A, Tuero E, et al. Diastolic dysfunction and COPD exacerbation. Postgrad Med. 2009;121(4):76–81.

Bhatt SP, Wells JM, Kinney GL, et al. β-Blockers are associated with a reduction in COPD Exacerbations. Thorax. Published Online First: [August 17, 2015] doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015–207251.

Short PM, Lipworth SI, Elder DH, et al. Effect of beta blockers in treatment of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2011;342:d2 549.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable

Funding

As a retrospective review, no additional funding was required as it pertains to this manuscript. Original data collection funded as noted in MACRO4 and STATCOPE3 trials.

Availability of data and materials

Data is from the cohorts from STATCOPE and MACRO trials.

Authors’ contributions

Concept and design, data interpretation, writing of manuscript, revision of manuscript: SD, RM, GJC. Data Analysis and interpretation: HV, JC. Original data collection and revision of manuscript: RA, WB, RC, JAC, JLC, MD, MKH, BM, NM, FM, SL, DN, PDS, FS, SS,RMR, GW, PW, CM, SA, DS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

Sean Duffy, MD- None

Robert Marron, MD- None

Helen Voelker, BA- None

Richard Albert, MD- No financial considerations for this manuscript. He has acted as a consultant for Gilead Sciences and provided expert testimony for the Bruce Fagel Law Firm in Beverly Hills, CA. He has a patent pending for a bed head elevation monitor. He has received royalties for book editing for Elsevier.

John Connett, PhD- No financial considerations for this manuscript. He has been awarded NHLBI-Lung division, NCI, and NIAID grants for other work. He is or has been a board member for NHLBI and NEI.

William Bailey, MD- None

Richard Casaburi, MD, PhD- No financial considerations for this manuscript. He has been compensated as an Advisory board member for Novartis Pharma and Forest Pharma. He has been compensated as a consultant for Theratechnologies, Inc, Breathe Technologies, Medtronic Inc. Spinal and Biologics, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Respironics Inc, Novartis Pharma, Actelion Pharma. His institution has been awarded grants by Novartis Pharma, Roche Pharma, Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharma, Osiris Pharma, Forest Pharma, Glaxo SmithKline Pharma, Breathe Technologies, and Theratechnologies Inc. He has been compensated as a speaker by Boehringer-Ingelheim Pharma, Astra Zeneca Pharma, and Pfizer Pharma. He has Stock or Stock options in Inogen, Inc.

J Allen Cooper, Jr, MD- No financial considerations for this manuscript. He has received a grant from Glaxo SmithKline and Novartis for work not associated with this manuscript. He has provided expert testimony for multiple law firms in malpractice cases and occupational lung disease cases.

Jefferey L. Curtis, MD- No financial considerations for this manuscript. He has received a grant to his institution from Boehringer-Ingelheim.

Mark Dransfield, MD- No financial considerations for this manuscript. He has received NIH grants to his institution in the past. He has been compensated as a consultant by Glaxo SmithKline, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Forest. He has received grants or has them pending from GSK, Boehringer Ingelheim, NIH, Boston Scientific. He has been compensated for lectures by GSK and Boehringer Ingelheim.

MeiLan K. Han, MD- No financial considerations for this manuscript. Has received a grant from NHLBI in the past to their institution. Has been compensated as a board member by CSL Behring, Glaxo SmithKline, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Has been compensated as a consultant by Genentech and Novartis. Has received or has grants pending from LAM Foundation, NHLBI, Chicago Community Trust to their institution. Has received payment for lectures from GSK, CSL Behring, Boehringer Ingelheim, Pfizer, National Association for Continuing Education. Has received royalties from UpToDate and payment for the development of educational presentations from the National Association for Continuing Education. Has received compensation for travel expenses from Astra Zeneca when attending a COPD symposium.

Barry Make, MD- No financial considerations for this manuscript. Has received a grant to his institution from NIH-NHLBI in the past and received compensation for travel for study design and implementation. Has been compensated as a board member by Forest, Astra Zeneca, Novartis, Dey, Nycomed, Respironics, Schering, Sequal, Embryon, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, and Glaxo SmithKline. Has been compensated as a consultant by Astellas, Talecris, and Chiesi. Has received a grant or has one pending to his institution from Astra Zeneca, GSK, Pfizer, NABI, Boehringer-Ingelheim, and Sunovian. Has received compensation or lectures by GSK, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Pfizer, Forest, and Astra Zeneca. Has received compensation from Boehringer-Ingelheim and Pfizer for video presentations. His institution has received compensation from Spiration for review of documents related to a clinical trial.

Nathaniel Marchetti, DO- No financial consideration for this manuscript. Has received a grant to his institution from NHLBI for past work and been compensated for relevant travel.

Fernando Martinez, MD- No financial consideration for this manuscript. Has received a NIH grant to his institution in the past. Has received compensation as a board member by Glaxo SmithKline, MedImmune/Astra Zeneca, Merck, Pearl, Novartis, UBC, MPex, and Ikaria. Has worked as a consultant and been compensated by Forest/Almirall, Boehringer Ingelheim, Nycomed/Forest, Roche, Bayer, Schering, HLS, Talecris, Comgenix, fb Communications, BoomComm, Actelion, Elan, Genzyme, Quark, Merck, Pfizer, and Sanofi-Aventis. Has received grants or has them pending to himself or his institution from Boehringer Ingelheim, Gilead, Johnson & Johnson/Centocor, Actelion, GSK, NACE, MedEd, Potomac, Pfizer, Schering, Vox Medic, American Lung Association, WebMD, ePocrates, Astra Zeneca, France Foundation, and Altana/Nycomed. Has received book royalties from Associates in Medical Marketing and Castle Connolly. Has received payment for the development of educational presentations by HIT Global, UpToDate, and the France Foundation.

Stephen Lazrus, MD- No financial considerations for this manuscript. Has received a grant from NIH-NHLBI for a past study and has received compensation for travel expenses to travel to CCRN Steering Meetings.

Dennis Niewoehner, MD- No financial consideration for this manuscript. In the past his institution has been awarded an NHLBI grant. Has been compensated as a consultant by Boehringer Ingelheim, Astra Zeneca, Glaxo SmithKline, Forest Research, Merck, Sanofi Aventis, Bayer Schering, Nycomed, Protaffin, and Pfizer.

Paul D. Scanlon, MD- No financial consideration for this manuscript. In the past has received institutional NHLBI grants and travel compensation. Has also received institutional grants from Dept. of Energy, Altana, Boehringer Ingelheim, Dey L.P. Pharmaceutical, Forest, Glaxo SmithKline, Novartis AG, and Pfizer. Has received royalties from Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins/Wolters Kluwer.

Frank Sciurba, MD- No relevant disclosures in 36 months prior to the submission of this manuscript.

Stephen Scharf, MD- No financial consideration for this manuscript. Has received an NIH grant to his institution, as well as NIH travel compensation and payment from the NIH for writing or reviewing of a manuscript.

Robert M. Reed, MD- None

George Washko, MD- No financial consideration for this manuscript. He has been compensated as consultant by MedImmune and Spiration.

Prescott Woodruff, MD, MPH- No financial consideration for this manuscript. Has been compensated as a consultant by MedImmune. Has received an institutional grant from Genentech. Has a patent or a patent pending for an asthma biomarker.

Charlene McEvoy, MD, MPH- No financial consideration for this manuscript. Has received a grant and travel expenses reimbursement by the NHLBI in the past. Has received and institutional grant from NHLBI, Boston Scientific, COPD Foundation, and Glaxo SmithKline. Has received speaking fees from Boehringer Ingelheim and Glaxo SmithKline.

Shawn Aaron, MD- None

Don Sin, MD, MPH- No financial considerations for this manuscript. In the past 36 months he has received grants from Astra Zeneca, Merck, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Gerard J. Criner, MD-No financial considerations for this manuscript. He has been awarded a grant for his institution from the NHLBI for other work.

Other grants from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Novartis, Astra Zeneca. He has received royalties from Springer for a book publication.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Ethics approval and consent to participate

IRB approval for this retrospective data review in accordance with COPD Clinical research network.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Duffy, S., Marron, R., Voelker, H. et al. Effect of beta-blockers on exacerbation rate and lung function in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Respir Res 18, 124 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0609-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-017-0609-7