Abstract

Background

Pulmonary system dysfunction is a hallmark of cystic fibrosis (CF) disease. In addition to impaired cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator protein, dysfunctional β2-adrenergic receptors (β2AR) contribute to low airway function in CF. Recent observations suggest CF may also be associated with impaired cardiac function that is demonstrated by attenuated cardiac output (Q), stroke volume (SV), and cardiac power (CP) at both rest and during exercise. However, β2AR regulation of cardiac and peripheral vascular tissue, in-vivo, is unknown in CF. We have previously demonstrated that the administration of an inhaled β-agonist increases SV and Q while also decreasing SVR in healthy individuals. Therefore, we aimed to assess cardiac and peripheral hemodynamic responses to the selective β2AR agonist albuterol in individuals with CF.

Methods

18 CF and 30 control (CTL) subjects participated (ages 22 ± 2 versus 27 ± 2 and BSA = 1.7 ± 0.1 versus 1.8 ± 0.0 m2, both p < 0.05). We assessed the following at baseline and at 30- and 60-minutes following nebulized albuterol (2.5mg diluted in 3.0mL of normal saline) inhalation: 12-lead ECG for HR, manual sphygmomanometry for systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBP and DBP, respectively), acetylene rebreathe for Q and SV. We calculated MAP = DBP + 1/3(SBP–DBP); systemic vascular resistance (SVR) = (MAP/Q)•80; CP = Q•MAP; stroke work (SW) = SV•MAP; reserve (%change baseline to 30- or 60-minutes). Hemodynamics were indexed to BSA (QI, SVI, SWI, CPI, SVRI).

Results

At baseline, CF demonstrated lower SV, SVI, SW, and SWI but higher HR than CTL (p < 0.05); other measures did not differ. At 30-minutes, CF demonstrated higher HR and SVRI, but lower Q, SV, SVI, CP, CPI, SW, and SWI versus CTL (p < 0.05). At 60-minutes, CF demonstrated higher HR, SVR, and SVRI, whereas all cardiac hemodynamics were lower than CTL (p < 0.05). Reserves of CP, SW, and SVR were lower in CF versus CTL at both 30 and 60-minutes (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Cardiac and peripheral hemodynamic responsiveness to acute β2AR stimulation via albuterol is attenuated in individuals with CF, suggesting β2AR located in cardiac and peripheral vascular tissue may be dysfunctional in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

A well-recognized phenotype of cystic fibrosis (CF) disease includes signs and symptoms of chronic sinusitis and pulmonary airway dysfunction, which are strong predictors of morbidity and mortality in individuals with this disease [1–6]. Primary structural and physiological changes that occur within the pulmonary system, including low airway surface fluid, attenuated mucociliary clearance, and airway obstruction are caused by mechanisms that impair chloride (Cl−) and sodium (Na+) regulation specifically related to malfunctioning or absent cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) protein, and impaired epithelial Na+ channel (ENaC) inhibition [2, 7–10]. Structural and physiological abnormalities of the pulmonary system in CF disease readily transgress to functional impairments as assessed by airway and gas-transfer tests. Low forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), attenuated capacity of gas transfer within lungs, and reduced oxygen uptake (VO2) at rest and during exercise are leading pulmonary system abnormalities in CF [4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12]; which, more importantly, strongly relate with morbidity and mortality in this population [1–3, 5, 6, 12].

Important evidence is accumulating that suggests certain individuals with CF demonstrate impaired β2-adrenergic receptor (β2AR) function in pulmonary airways [13–19]. Blunted resting pulmonary airway function in addition to attenuated airway responsiveness following inhalation of the selective β2AR agonist albuterol may be linked to dysfunction of airway β2AR in CF [13, 14]. In fact, Marson et al. further suggests that impaired spirometry responses following inhalation of albuterol indicates disease severity in CF [14].

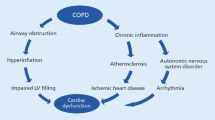

In this context and taking into account that β2AR are found in abundant concentrations in pulmonary as well as cardiac and systemic vascular tissue [13–20]; observations relating pulmonary airway dysfunction to impaired airway β2AR in CF are noteworthy and may have critical clinical implications in this population [13, 14, 19]. As such, our group and others have shown that individuals with CF demonstrate attenuated cardiac output (Q), large arterial dysfunction, abnormal ventilatory mechanics, and attenuated lung gas-transfer [8, 9, 11, 12, 21]. Cumulatively, these observations suggest that there is global cardiovascular system impairment in individuals with CF; and, that the hallmark clinical phenotype of this disease is not isolated to pulmonary system dysfunction.

Accordingly, because we have previously demonstrated that inhalation of albuterol evokes increases in Q and stroke volume (SV) that accompany decreases in systemic vascular resistance (SVR) in healthy individuals [22], the aim of the present study was to assess cardiac and peripheral vascular function in response to acute inhalation of the β2AR selective-agonist albuterol in order to enhance our understanding of whether pathways related to β2AR in cardiac and peripheral vascular tissue are impaired, and associated with attenuated cardiac and peripheral vascular hemodynamic function in individuals with CF.

Methods

Participants

Forty-eight adults participated in this cross-sectional study (CF = 18; healthy individuals = 30 [controls]) (characteristics, Table 1). Cystic fibrosis in individuals was confirmed by a positive sweat test (≥60.0 millimole/liter Cl−) and genotyping of the ∆F508 mutation of CFTR. Individuals with CF who met the following exclusion criteria were not enrolled due to safety concerns: experienced a pulmonary exacerbation within the last two weeks or pulmonary hemorrhage within six months resulting in greater than 50 cc of blood in the sputum, were taking any antibiotics for pulmonary exacerbation, or if they were taking any experimental drugs related to CF. The Arizona Respiratory Center and its affiliated CF clinic at the University of Arizona Medical Center were used to recruit all individuals with CF. Word of mouth and posted advertising around the University of Arizona were used to recruit control participants. The protocol was reviewed and approved by the University of Arizona Institutional Review Board. All participants provided written informed consent prior to study, and all aspects of the study were performed according to the Declaration of Helsinki.

Protocol overview

Prior to arrival for study participation, individuals were asked to refrain from caffeine and exercise for 24 h before arrival for study testing. Upon arrival to the environmentally controlled physiology laboratory for baseline testing, participants were fitted with a 12-lead electrocardiogram (Marquette Electronics, Milwaukee, WI) to monitor heart rate (HR) and rhythm. A single venous puncture blood draw (2 × 5 mL samples) occurred to assess hemoglobin and renal function. Following blood sampling standard pulmonary function testing (i.e. flow volume loop: forced expiratory volume at 25 to 75 % of FVC (FEF25-75), forced expiratory volume at 25 % of FVC (FEF25), forced expiratory volume at 50 % of FVC (FEF50), and forced expiratory volume at 75 % of FVC (FEF75)) in a seated upright position, using a Medical Graphics CPFS system spirometer (Medical Graphics, St. Paul, MN) according to the guidelines of the American Thoracic Society were performed in triplicate to ensure all measures fell within 10 % of each attempt [23]. Remaining in the upright position, participants had systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) pressures assessed using manual sphygmomanometry. Assessment of Q followed using the acetylene rebreathe technique as described previously and in brief below [24]. All cardiovascular measurements were performed at baseline and at both 30-minutes (30min) and 60-minutes (60min) following administration of albuterol (described below). For each measurement time point we calculated the following: mean arterial blood pressure (MAP) = DBP + 1/3(SBP–DBP); body mass index = weight/height2; body surface area (BSA)= \( \sqrt{\left(\mathrm{height}\kern0.2em \times \kern0.2em \mathrm{weight}\kern0.2em /\kern0.2em 3600\right)} \); SVR=(MAP/Q)•80; SV=Q/HR; cardiac power (CP)=Q•MAP; stroke work (SW)=SV•MAP; and reserve (delta=30- or 60-minutes minus baseline; or, percentage change=baseline to 30min or 60min) [25–27]. All cardiac hemodynamic measurements and SVR were also indexed separately to BSA: CPI, SWI, SVI, QI, and SVRI.

Although not a primary aim of this study, to assess overall functional capacity (i.e. peak VO2), participants performed a seated upright peak cycle ergometry test to volitional fatigue (symptom limited) as described and reported previously by our group [8]. This assessment occurred on a separate study visit that was separated by at least 48 h but no greater than 1 week prior to participation in the present study. Predicted peak VO2 values were calculated according to Hansen et al. [28].

Administration of albuterol

Following baseline testing and a brief rest period, participants were instructed to complete inhalation of the selective β2AR agonist albuterol (albuterol sulfate 2.5 mg diluted in 3.0 mL of normal saline) using a mouthpiece connected to a nebulizer (Power Neb2 nebulizer, Port Washington, NY) in a seated upright position. Using the mouthpiece—nebulizer system, individuals were instructed to breathe in calmly, deeply, and evenly for about 5-15 minutes until mist stopped forming in the nebulizer chamber. At 30min and 60min following albuterol administration, blood pressures were assessed in addition to Q in a similar manner to baseline.

Measurement of cardiac output

In a seated upright position, participants breathed into a non-rebreathing technician controlled pneumatic switching Y-valve that was connected to a pneumotachometer and mass spectrometer. The inspiratory port of the switching valve allowed for rapid operator controlled switching between breathing room air or from a 5.0 L anesthesia rebreathe bag containing 1575 mL of test gas (0.65 % acetylene [C2H2], 9.0 % helium [He], 55.0 % nitrogen, and 35.0 % O2 as previously described [24].

Each rebreathe measurement period consisted of 8-10 consecutive breaths set at a cadence of 32 breaths/min using a metronome. During each rebreathe period, individuals were instructed to nearly empty the bag with each inspiration while the mass spectrometer was used to collect serial measurement of gas concentrations starting at end-expiration of the first breath during the rebreathe period which enabled rapid calculations of Q [24]. Acetylene disappears in the blood according to the rate at which pulmonary blood flow occurs, and therefore Q is calculated from the slope of the exponential disappearance of acetylene with respect to the insoluble gas He [24, 29, 30].

Statistical analysis

All parametric data are presented as means ± standard error mean (SEM). The data were distributed normally. Homogeneity of variance of data was confirmed using Levene’s test. For comparisons of participant characteristics, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests were performed for variables except gender, which was compared using a χ2 test. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measures was used to test for the effect of participant and repeated measurement of hemodynamics. In the event of a significant F-test statistic, post-hoc testing with a Bonferroni correction was used. In addition, post-hoc Cohen’s d effect sizes (small=0.2; medium= 0.5; and large=0.8) were calculated to estimate the magnitude of effects for differences between groups at each level of time for cardiac hemodynamic and SVR indices [31, 32]. The alpha level was set at 0.05 to determine two-tailed statistical significance. All computations were made using SAS statistical software v.9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Study population

Baseline participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. Although controls did not have significantly higher body weight or body mass index compared to CF, none of the controls had evidence of nutritional deficiency. Although the absolute dose of albuterol was identical for all participants, because of the low body weight in individuals with CF, the dose of albuterol standardized for body weight resulted in a higher dose in CF compared to controls. Compared to controls, CF demonstrated lower functional capacity as indicated by a lower VO2peak and percentage achieved of predicted VO2peak. As expected, spirometry tests prior to albuterol inhalation indicated pulmonary airway function was normal in controls but not in CF.

Heart rate and peripheral vascular hemodynamics

Reported in Table 2 are absolute measurements of HR, SBP, DBP, MAP, SVR, and SVRI assessed at baseline and at 30 and 60 min following inhalation of albuterol in participants. No significant interaction was observed for any test. Fixed effects from ANOVA models for participant (CF and controls) and condition (baseline, 30 min, and 60 min) were F(1, 47) = 10.91, p = 0.002, and F(2, 96) = 4.73, p = 0.011 for SVR, respectively; and, F(1, 47) = 18.13, p<0.0001, and F(2, 96) = 3.61, p = 0.0308 for SVRI, respectively.

At baseline, modest tachycardia was present in CF versus controls; although, all other variables were similar between groups. Differences in HR between groups at rest persisted to 30min (p<0.05), which was accompanied by higher SVRI in CF compared to controls (p<0.05). Differences between groups at 30min persisted to 60min, which included significance for HR, SVR, and SVRI. Cohen’s d effect sizes between CF and controls for SVR and SVRI progressively increased from baseline (0.31 and 0.50) to 30min (0.54 and 0.73) to 60min (0.82 and 0.93), respectively, suggesting that the differences between groups could be largely attributable to CF disease.

Within group differences comparing baseline to 30 or 60 min following albuterol showed no significant differences for any metric in CF. In contrast, at baseline, both SVR and SVRI were significantly higher compared to 60min in controls, suggesting an influence of albuterol on increasing systemic vascular conductivity and permeability in controls.

Cardiac hemodynamics

Presented in Table 3 are traditional measures of cardiac hemodynamics including Q, QI, SV, and SVI, in addition to measures of cardiac pumping capability (i.e. CP, CPI, SW, and SWI) [25, 27]. No significant interaction effects were observed. From baseline to 60min, differences between groups in cardiac hemodynamics progressively increased, which were mainly due lack of increases in CF. This suggested that there was an influence of albuterol inhalation on increasing cardiac hemodynamics and arterial pressure generation in controls but not in CF. Increased effect sizes from baseline to 60 min following albuterol inhalation suggested that the differences between groups for cardiac hemodynamics were likely due to null responses in CF (Table 3).

Cardiac and peripheral hemodynamic reserve

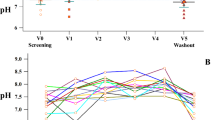

Presented in Figs. 1, 2 and 3 are CP, CPI, SW, SWI, SVR, and SVRI reserves measured as differences between baseline and 30min or 60min following albuterol inhalation in participants.

Data presented as means ± standard error mean. Cystic fibrosis (CF, n=18); healthy controls (CTL, n=30). Cardiac hemodynamic reserves calculated as the delta (Δ) at 30 or 60 minutes following albuterol inhalation minus baseline. Panels A and B, show reserves of cardiac power or cardiac power indexed for body surface areas (BSA) in individuals with CF versus CTL. Panels C and D, show reserves of stroke work (SW) or SW indexed for BSA in individuals with CF versus CTL. *CF versus CTL, p<0.05; †Within group, p<0.05

Data presented as means ± standard error mean. Cystic fibrosis (CF, n=18); healthy controls (CTL, 10.1186/s12931-015-0270-y n=30). Cardiac hemodynamic reserves calculated as a percentage change (%) from baseline to 30 or 60 minutes following albuterol inhalation. Panel A, shows cardiac power reserve indexed to body surface area (BSA) in individuals with CF versus CTL. Panel B, shows stroke work reserve indexed to BSA in individuals with CF versus CTL. *CF versus CTL, p<0.05; †Within group, p<0.05

Data presented as means ± standard error mean. Cystic fibrosis (CF, n=18); healthy controls (CTL, n=30). Panel A, systemic vascular resistance (SVR) reserve indexed to body surface area was calculated as delta (Δ) at 30 or 60 minutes following albuterol inhalation minus baseline in individuals with CF versus CTL. Panel B, SVR index calculated as the percentage change (%) from baseline to 30 or 60 minutes following albuterol inhalation in individuals with CF versus CTL. *CF versus CTL, p<0.05

We report in Fig. 1 (a–d), absolute differences (∆) between baseline and 30min or 60min for CP, CPI, SW, and SWI following albuterol inhalation in CF and controls. In Panel A, Cohen’s d effect sizes between CF and controls for ΔCP were 0.62 at 30min and 0.77 at 60 min. In Panel B, Cohen’s d effect sizes between groups for ΔCPI were 0.66 at 30 min and 0.73 at 60 min. In Panel C, Cohen’s d effect sizes between groups for ΔSW were 0.67 at 30 min and 0.99 at 60 min. In Panel D, Cohen’s d effect sizes between groups for ΔSWI were 0.71 at 30 min and 1.01 at 60 min. The effect sizes at 30 min and to a greater extent at 60 min suggested a strong influence of CF disease on cardiac hemodynamic reserve responses to albuterol.

In Fig. 2 (a and b), we show percentage (%) change from baseline to 30min or 60min for CPI and SWI following inhalation of albuterol in CF and controls. Consistent with Fig. 1 (a–d) at 30 min in CF, there was a profound decrease in %SWI at 30min following albuterol inhalation in CF. In Panel A, Cohen’s d effect sizes between CF and controls for %CPI were 0.60 at 30 min and 0.75 at 60 min. In Panel B, Cohen’s d effect sizes between CF and controls for %SWI were 0.81 at 30 min and 1.05 at 60 min. Observations in Fig. 2 (a and b) were consistent with Fig. 1 (a–d) for absolute differences.

Lastly, Fig. 3 (a and b) shows Δ and % change, respectively, for SVRI from baseline to 30 min or 60 min following inhalation of albuterol in participants. In Panel A, Cohen’s d effect sizes between CF and controls for ΔSVRI were 0.24 at 30 min and 0.74 at 60 min. In Panel B, Cohen’s d effect sizes between CF and controls for %SVRI were 0.27 at 30 min and 0.84 at 60 min. These effect sizes suggested that there was a strong influence of CF disease on the attenuated SVRI response to albuterol at 60 min and to a lesser extent at 30 min.

Overall, cardiac and SVR reserves were consistent with absolute measures presented in Tables 2 and 3, suggesting individuals with CF did not demonstrate normal cardiac and peripheral hemodynamic reserve responses to the β2AR selective-agonist albuterol.

Discussion

In this study we present novel observations which suggest that individuals with CF demonstrate attenuated cardiac and peripheral hemodynamic responses to acute inhalation of the β2AR selective-agonist albuterol. The present findings support the hypothesis that mechanistic pathways closely associated with impaired β2AR function are likely determinants of cardiac and peripheral vascular dysfunction in CF. In this context, we show, 1) although absolute measures of baseline SV and SW are significantly lower in CF compared to controls, this attenuation in CF persists even with β2AR stimulation via albuterol. Whereas, in response to albuterol inhalation, healthy individuals in the present study and previously [22] demonstrate significant increases in cardiac hemodynamics; 2) similar to null cardiac hemodynamic responses to albuterol inhalation, vascular conductivity and permeability indicated by absolute measures of SVR are not responsive to albuterol inhalation in CF. In contrast, and consistent with previous observations from our group [22], reductions in SVR at 60 min following albuterol in healthy individuals suggest that improvements in peripheral vascular conductivity are related to β2AR stimulation; 3) differences in cardiac and peripheral hemodynamics from baseline to 30 or 60 min following albuterol inhalation suggest that individuals with CF are nearly entirely absent of cardiac and peripheral hemodynamic reserves, whereas healthy individuals are not; and finally, 4) although we did not assess exercise responses in the present study, these data are consistent with previous observations which clearly demonstrate that individuals with CF have attenuated cardiac hemodynamic responses to exercise and, hence, impaired cardiac reserve [9, 11]. Therefore, because arterial pressure is highly blood-flow mediated in the presence of intact cardiac hemodynamic function [33, 34], a decrease in vasodilatory reserve accompanied by an attenuated rise in cardiac hemodynamics could likely explain negligible SVR decreases following albuterol inhalation in CF.

Recent observations in animal models of CF suggest that abnormal cardiac structure, rhythmicity, and contractility in CF are associated with absent and/or dysfunctional CFTR [35, 36]. This is important since mutations in genes coding for CFTR are the cause of CF, and deranged or absent expression of CFTR is responsible for mechanisms leading to pulmonary dysfunction in individuals with this disease [2, 7–10].

The role of CFTR in contributing to the maintenance of electrochemical ion balance extends beyond the pulmonary system, whereby functional CFTR mediate protein kinase A-stimulated Cl− currents in myocardial tissue, which is a relationship suggested to act to protect against ischemia or rhythm disturbances [37]. However, despite a well-known presence of β2AR in myocardial tissue, which are critically important in compensating for loss of β1AR and contractility, particularly in the condition of heart failure [20]; to date, it remains unclear what role impaired β2AR have in mediating cardiac dysfunction in CF. In this context, this is a noteworthy gap in knowledge as it is suggested that β2AR may have an important role in regulating CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion and intracellular Ca2+ in the pulmonary system [38–41]. Thus, despite a more clear understanding of relationships between CFTR and β2AR pathways in pulmonary function [40, 42], any link CFTR shares with β2AR responsiveness in cardiac and peripheral vascular tissue is currently unknown in CF disease. This is an important question to answer since individually, or in an integrated capacity, mechanisms of CFTR, β2AR, and global cardiovascular system function appear related and markedly impaired in individuals with CF.

Although yet to be fully elucidated, it has been observed that alpha-1 adrenergic receptor (α1AR) sensitivity may be augmented in CF [43], which could lead to abnormal decreases in vasodilatory reserve. A heightened α1AR effector response of coronary and peripheral arteries to selective adrenergic sensitization could exacerbate a state of attenuated β2AR function. Hyperexcitability of α1AR in parallel with blunted systemic β2AR activity could lead to attenuated vasodilatory reserve and, hence, a negligible drop in SVR following albuterol inhalation. Therefore, because both α1- and β2-AR are highly involved in the regulation of Ca2+ flux that is essential for normal excitability and excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes and relaxation in smooth muscle [44–47], paradoxical differences in α1- and β2-AR receptor responsiveness may have critical consequences on cardiac and peripheral vascular function in CF. Dual, but imbalanced, sensitization of α1- and β2-AR via albuterol in cardiac and vascular tissue, where α1AR sensitivity is heightened and β2AR responsiveness is blunted could result in a critical reduction in intracellular Ca2+, thereby leading to an impaired rise in myocardial contractility that is accompanied by decreased relaxation of smooth muscle [46].

As such, because of shared pathways which contribute to the influence of β2AR on CFTR-mediated Cl− regulation [38–42]; impaired β2AR, CFTR, Cl−, and Ca2+ mechanisms likely play a critical role in the cardiac and peripheral vascular hemodynamic health of individuals with CF. The present observations demonstrate clinical relevance as they suggest that β2AR selective-agonist therapy intended to alleviate signs and symptoms of pulmonary dysfunction in CF may be contraindicated in certain individuals. β2AR selective-agonists such as albuterol could augment effector responses of α1AR stimulation in the presence of diminished β2AR function. This could potentially contribute to an exacerbation of Ca2+ and Cl− channel dysregulation leading to impaired excitation-contraction coupling in cardiac myocytes and uncoupling in smooth muscle and, hence, cardiac dysfunction concurrent with attenuations in vascular permeability and conductivity in individuals with CF. Moreover, as β1AR outnumber β2AR in a ~3:1 ratio in cardiac tissue [20], while also demonstrating sensitivity (lesser) to albuterol [48], acute increases in HR may indeed be a potential consequence of β2AR selective-agonist therapy, thereby causing unanticipated tachycardia. Although, consistent with pharmacokinetic studies of albuterol in CF and in healthy individuals [49], tachycardia that individuals with CF demonstrated in the present study was not likely due to the influences of albuterol, since elevated HR at rest persisted, but did not increase further at 30- and 60-minutes following albuterol.

These data present novel evidence for the potential role of cardiac and smooth muscle tissue β2AR pathways as targets for novel therapies in the management of signs and symptoms associated with global cardiovascular dysfunction in individuals with CF.

Limitations

The present study was a cross-sectional design and pharmacokinetic testing was not conducted to assess systemic absorption of albuterol. However, both albuterol and method of delivery utilized in the present study have been previously demonstrated to elicit pulmonary function responses in CF and in healthy individuals and, therefore, we do not believe another confounding factor was causal for hemodynamic responses measured at 30 and 60 min following albuterol inhalation [13, 14, 22]. Moreover, detailed pharmacokinetic studies of inhaled albuterol in CF and healthy individuals show that despite similar inhaled body weight standardized dose concentrations of albuterol, albuterol absorption in the systemic circulation is markedly higher in CF compared to controls (area under the curve=1051.6±256.2 vs. 277.5±91.5 ng×sec/mL, respectively) [49]. Also, in comparison to systemic absorption of albuterol, it is estimated that only ~10% of inhaled albuterol is absorbed in pulmonary tissue [49], suggesting that in the presence of intact β2AR, there is a stronger likelihood of response at the systemic level compared to the pulmonary system. Lastly, the present study did not specifically test β1AR or α1AR function, nor intracellular Ca2+ or Cl− as a result of albuterol inhalation in participants. Therefore, our hypotheses regarding the relationships between these factors warrants further study of the integrated roles of CFTR, α1AR, β1,2AR, Ca2+, Cl−, and cardiac and vascular function in individuals with CF.

Conclusions

The major findings of this study suggests that individuals with CF do not demonstrate cardiac and peripheral vascular hemodynamic responsiveness to the short-acting β2AR selective-agonist albuterol that mirror normal responses of healthy individuals. We suggest that null cardiac and peripheral vascular hemodynamic responses to acute albuterol inhalation in individuals with CF are likely due to deranged β2AR function, closely accompanied by impaired CFTR and related pathways leading to augmented Cl− and Ca2+ dysregulation in cardiac and vascular smooth muscle.

Abbreviations

- α1AR:

-

alpha-1 adrenergic receptor

- β1AR:

-

beta-1 adrenergic receptor

- β2AR:

-

beta-2 adrenergic receptor

- BSA:

-

Body surface area

- Ca2+ :

-

Calcium

- CF:

-

Cystic fibrosis

- CFTR:

-

Cystic fibrosis conductance regulator

- Cl− :

-

Chloride

- CP:

-

Cardiac power

- DBP:

-

Diastolic blood pressure

- ENaC:

-

Epithelial Na+ channel

- FEF25-75:

-

Forced expiratory volume at 25 to 75 % of FVC

- FEF25:

-

Forced expiratory volume at 25 % of FVC

- FEF50:

-

Forced expiratory volume at 50 % of FVC

- FEF75:

-

FEV1: forced expiratory volume in 1-second; forced expiratory volume at 75 % of FVC

- FVC:

-

Forced vital capacity

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- MAP:

-

Mean arterial pressure

- Na+ :

-

Sodium

- Q:

-

Cardiac output

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- SV:

-

Stroke volume

- SVR:

-

Systemic vascular resistance

- SW:

-

Stroke work

- VO2 :

-

Oxygen uptake

References

Kerem E, Reisman J, Corey M, Canny GJ, Levison H. Prediction of mortality in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1992;326:1187–91.

Farrell PM, Rosenstein BJ, White TB, Accurso FJ, Castellani C, Cutting GR, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis of cystic fibrosis in newborns through older adults: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation consensus report. J Pediatr. 2008;153:S4–14.

Milla CE, Warwick WJ. Risk of death in cystic fibrosis patients with severely compromised lung function. Chest. 1998;113:1230–4.

Flume PA, Mogayzel Jr PJ, Robinson KA, Goss CH, Rosenblatt RL, Kuhn RJ, et al. Cystic fibrosis pulmonary guidelines: treatment of pulmonary exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:802–8.

Liou TG, Adler FR, FitzSimmons SC, Cahill BC, Hibbs JR, Marshall BC. Predictive 5-year survivorship model of cystic fibrosis. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:345–52.

Courtney J, Bradley J, Mccaughan J, O’connor T, Shortt C, Bredin C, et al. Predictors of mortality in adults with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2007;42:525–32.

Puchelle E, Gaillard D, Ploton D, Hinnrasky J, Fuchey C, Boutterin MC, et al. Differential localization of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in normal and cystic fibrosis airway epithelium. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;7:485–91.

Baker SE, Wong EC, Wheatley CM, Foxx-Lupo WT, Martinez MG, Morgan MA, et al. Genetic variation of SCNN1A influences lung diffusing capacity in cystic fibrosis. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44:2315–21.

Wheatley CM, Foxx-Lupo WT, Cassuto NA, Wong EC, Daines CL, Morgan WJ, et al. Impaired lung diffusing capacity for nitric oxide and alveolar-capillary membrane conductance results in oxygen desaturation during exercise in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2011;10:45–53.

Dalemans W, Barbry P, Champigny G, Jallat S, Dott K, Dreyer D, et al. Altered chloride ion channel kinetics associated with the delta F508 cystic fibrosis mutation. Nature. 1991;354:526–8.

Lands LC, Heigenhauser GJ, Jones NL. Cardiac output determination during progressive exercise in cystic fibrosis. Chest. 1992;102:1118–23.

Nixon PA, Orenstein DM, Kelsey SF, Doershuk CF. The prognostic value of exercise testing in patients with cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1992;327:1785–8.

Hart MA, Konstan MW, Darrah RJ, Schluchter MD, Storfer-Isser A, Xue L, et al. Beta 2 adrenergic receptor polymorphisms in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2005;39:544–50.

Marson FAL, Bertuzzo CS, Ribeiro AF, Ribeiro JD. Polymorphisms in ADRB2 gene can modulate the response to bronchodilators and the severity of cystic fibrosis. BMC Pulmonary Med. 2012;12:50.

Shapiro GG, Bamman J, Kanarek P, Bierman CW. The paradoxical effect of adrenergic and methylxanthine drugs in cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics. 1976;58:740–3.

Featherby EA, Weng TR, Levison H. The effect of isoproterenol on airway obstruction in cystic fibrosis. Can Med Assoc J. 1970;102:835–8.

Larsen GL, Barron RJ, Cotton EK, Brooks JG. A comparative study of inhaled atropine sulfate and isoproterenol hydrochloride in cystic fibrosis. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1979;119:399–407.

Büscher R, Eilmes KJ, Grasemann H, Torres B, Knauer N, Sroka K, et al. β2 adrenoceptor gene polymorphisms in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2002;12:347–53.

Steagall WK, Barrow BJ, Glasgow CG, Mendoza JW, Ehrmantraut M, Lin J-P, et al. Beta-2-adrenergic receptor polymorphisms in cystic fibrosis. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:425.

Bristow M, Hershberger R, Port J, Gilbert E, Sandoval A, Rasmussen R, et al. Beta-adrenergic pathways in nonfailing and failing human ventricular myocardium. Circulation. 1990;82:I12–25.

Hull JH, Ansley L, Bolton CE, Sharman JE, Knight RK, Cockcroft JR, et al. The effect of exercise on large artery haemodynamics in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros. 2011;10:121–7.

Snyder EM, Wong EC, Foxx‐Lupo WT, Wheatley CM, Cassuto NA, Patanwala AE. Effects of an Inhaled β2-Agonist on Cardiovascular Function and Sympathetic Activity in Healthy Subjects. Pharmacotherapy. 2011;31:748–56.

Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–38.

Snyder EM, Johnson BD, Beck KC. An open-circuit method for determining lung diffusing capacity during exercise: comparison to rebreathe. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2005;99:1985–91.

Lang CC, Karlin P, Haythe J, Lim TK, Mancini DM. Peak cardiac power output, measured noninvasively, is a powerful predictor of outcome in chronic heart failure. Circ Heart Fail. 2009;2:33–8.

Cotter G, Moshkovitz Y, Kaluski E, Milo O, Nobikov Y, Schneeweiss A, et al. The role of cardiac power and systemic vascular resistance in the pathophysiology and diagnosis of patients with acute congestive heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003;5:443–51.

Bromley PD, Hodges LD, Brodie DA. Physiological range of peak cardiac power output in healthy adults. Clin Physiol Funct Imaging. 2006;26:240–6.

Hansen JE, Sue DY, Wasserman K. Predicted values for clinical exercise testing. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;129:S49–55.

Hsia CC, Herazo LF, Ramanathan M, Johnson Jr RL. Cardiac output during exercise measured by acetylene rebreathing, thermodilution, and Fick techniques. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1995;78:1612–6.

Johnson BD, Beck KC, Proctor DN, Miller J, Dietz NM, Joyner MJ. Cardiac output during exercise by the open circuit acetylene washin method: comparison with direct Fick. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000;88:1650–8.

Nakagawa S, Cuthill IC. Effect size, confidence interval and statistical significance: a practical guide for biologists. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2007;82:591–605.

Lakens D. Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: a practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Front Psychol. 2013;4:863.

Ichinose MJ, Sala-Mercado JA, Coutsos M, Li Z, Ichinose TK, Dawe E, et al. Modulation of cardiac output alters the mechanisms of the muscle metaboreflex pressor response. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010;298:H245–50.

Spranger MD, Sala-Mercado JA, Coutsos M, Kaur J, Stayer D, Augustyniak RA, et al. Role of cardiac output versus peripheral vasoconstriction in mediating muscle metaboreflex pressor responses: dynamic exercise versus postexercise muscle ischemia. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2013;304:R657–63.

Sellers ZM, Kovacs A, Weinheimer CJ, Best PM. Left ventricular and aortic dysfunction in cystic fibrosis mice. J Cyst Fibros. 2013;12:517–24.

Sellers ZM, Naren AP, Xiang Y, Best PM. MRP4 and CFTR in the regulation of cAMP and beta-adrenergic contraction in cardiac myocytes. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;681:80–7.

Duan DY, Liu LL, Bozeat N, Huang ZM, Xiang SY, Wang GL, et al. Functional role of anion channels in cardiac diseases. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:265–78.

Naren AP, Cobb B, Li C, Roy K, Nelson D, Heda GD, et al. A macromolecular complex of beta 2 adrenergic receptor, CFTR, and ezrin/radixin/moesin-binding phosphoprotein 50 is regulated by PKA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:342–6.

Uezono Y, Bradley J, Min C, McCarty N, Quick M, Riordan J, et al. Receptors that couple to 2 classes of G proteins increase cAMP and activate CFTR expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Receptors Channels. 1992;1:233–41.

Taouil K, Hinnrasky J, Hologne C, Corlieu P, Klossek J-M, Puchelle E. Stimulation of β2 adrenergic receptor increases CFTR expression in human airway epithelial cells through a c-AMP/protein kinase A-independent pathway. J Biol Chem. 2003.

McCann JD, Bhalla RC, Welsh MJ. Release of intracellular calcium by two different second messengers in airway epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1989;257:L116–24.

Wheatley CM, Wilkins BW, Snyder EM. Exercise is medicine in cystic fibrosis. Exerc Sport Sci Rev. 2011;39:155–60.

Davis PB, Shelhamer JR, Kaliner M. Abnormal adrenergic and cholinergic sensitivity in cystic fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1980;302:1453–6.

Xiao RP, Lakatta EG. Beta 1-adrenoceptor stimulation and beta 2-adrenoceptor stimulation differ in their effects on contraction, cytosolic Ca2+, and Ca2+ current in single rat ventricular cells. Circ Res. 1993;73:286–300.

Altschuld RA, Starling RC, Hamlin RL, Billman GE, Hensley J, Castillo L, et al. Response of failing canine and human heart cells to beta 2-adrenergic stimulation. Circulation. 1995;92:1612–8.

Boutjdir M, Restivo M, Wei Y, el-Sherif N. Alpha 1- and beta-adrenergic interactions on L-type calcium current in cardiac myocytes. Pflugers Arch. 1992;421:397–9.

Hool LC, Arthur PG. Decreasing cellular hydrogen peroxide with catalase mimics the effects of hypoxia on the sensitivity of the L-type Ca2+ channel to beta-adrenergic receptor stimulation in cardiac myocytes. Circ Res. 2002;91:601–9.

Newnham D, Wheeldon N, Lipworth B, McDevitt D. Single dosing comparison of the relative cardiac beta 1/beta 2 activity of inhaled fenoterol and salbutamol in normal subjects. Thorax. 1993;48:656–8.

Vaisman N, Koren G, Goldstein D, Canny GJ, Tan Y, Soldin S, et al. Pharmacokinetics of inhaled salbutamol in patients with cystic fibrosis versus healthy young adults. J Pediatr. 1987;111:914–7.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (HL108962-03) and the University of Arizona Clinical Scholar Program. Thank you to the individuals who participated in this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design: EMS, CMW, and SEB. Acquisition of data: EMS, CMW, and SEB. Analysis and interpretation: EHV and EMS. Drafting the article for important intellectual content: EHV, EMS, SRK, CMW, SEB, and WJM. All authors contributed to the intellectual content of the manuscript and were consulted for final approval of the submitted version.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Van Iterson, E.H., Karpen, S.R., Baker, S.E. et al. Impaired cardiac and peripheral hemodynamic responses to inhaled β2-agonist in cystic fibrosis. Respir Res 16, 103 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0270-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0270-y