Abstract

Background

Tobacco-induced pulmonary vascular disease is partly driven by endothelial dysfunction. The bioavailability of the potent vasodilator nitric oxide (NO) depends on competition between NO synthase-3 (NOS3) and arginases for their common substrate (L-arginine). We tested the hypothesis whereby tobacco smoking impairs pulmonary endothelial function via upregulation of the arginase pathway.

Methods

Endothelium-dependent vasodilation in response to acetylcholine (Ach) was compared ex vivo for pulmonary vascular rings from 29 smokers and 10 never-smokers. The results were expressed as a percentage of the contraction with phenylephrine. We tested the effects of L-arginine supplementation, arginase inhibition (by N(omega)-hydroxy-nor-l-arginine, NorNOHA) and NOS3 induction (by genistein) on vasodilation. Protein levels of NOS3 and arginases I and II in the pulmonary arteries were quantified by Western blotting.

Results

Overall, vasodilation was impaired in smokers (relative to controls; p < 0.01). Eleven of the 29 smokers (the ED+ subgroup) displayed endothelial dysfunction (defined as the absence of a relaxant response to Ach), whereas 18 (the ED− subgroup) had normal vasodilation. The mean responses to 10−4 M Ach were −23 ± 10% and 31 ± 4% in the ED+ and ED− subgroups, respectively (p < 0.01). Supplementation with L- arginine improved endothelial function in the ED+ subgroup (−4 ± 10% vs. -32 ± 10% in the presence and absence of L- arginine, respectively; p = 0.006), as did arginase inhibition (18 ± 9% vs. -1 ± 9%, respectively; p = 0.0002). Arginase I protein was overexpressed in ED+ samples, whereas ED+ and ED− samples did not differ significantly in terms of NOS3 expression. Treatment with genistein did not significantly improve endothelial function in ED+ samples.

Conclusion

Overexpression and elevated activity of arginase I are involved in tobacco-induced pulmonary endothelial dysfunction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

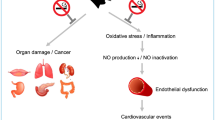

Tobacco smoking can induce pulmonary vascular remodelling – even in individuals with normal or slightly impaired lung function [1]. This remodelling can lead to increased pulmonary vascular resistance and then pulmonary hypertension (PH). As a well characterized feature of end-stage chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [2], PH can also develop in milder forms of COPD and is acknowledged to be a significant clinical issue with a strong, negative impact on the prognosis [3]. Pulmonary endothelial dysfunction is thought to be an early pathophysiological determinant of vascular remodelling. The condition is present in end-stage COPD [4] but has also been observed in milder forms of COPD and in smokers without COPD [5]. The mechanisms of pulmonary endothelial dysfunction have not been well elucidated but may be based (at least in part) on (i) imbalance between the production of vasoconstrictive and vasodilatory factors and (ii) low bioavailability of nitric oxide (NO) [6], which is a potent vasodilator and decreases vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. The production of NO by endothelial nitric oxide synthase (NOS3) is dependent on the balance between the expression and/or activity of arginases and NOS3. In the vasculature, NOSs and arginases compete for their common substrate L-arginine (L-arg). Elevated arginase activity reduces the availability of L-arg for NOS3 and thus decreases the production of NO. In addition, arginases I and II (which are also expressed by endothelial cells) produce urea and L-ornithine [7,8]. L-ornithine metabolism produces polyamines and proline, which are involved in pulmonary vascular remodelling [9]. Consequently, arginases and NOS may have opposing effects on vascular tone and tissue remodelling [10]. Over the last few years, it has become increasingly clear that arginases have a harmful role in systemic vascular conditions in animal models and in humans (including atherosclerosis, coronary artery disease, myocardial ischemia-reperfusion, diabetes mellitus, heart failure, hypertension and ageing) [11-18]. Cigarette smoke can increase arginase activity and protein expression in systemic vessels or in the lung [19-21]. Although arginases are also expressed in the pulmonary vasculature, [22,23] there are no literature data on the latter’s role in tobacco-induced pulmonary endothelial dysfunction in humans.

Hence, we decided to test the hypothesis whereby tobacco smoking impairs pulmonary endothelial function through upregulation of the arginase pathway.

Methods

We obtained explants from current smokers, ex-smokers or never-smokers undergoing lung resection for lung cancer in a major university hospital (Hôpital Européen George Pompidou, Paris, France). The study’s objectives and procedures were approved by the local independent ethics committee, and all patients gave their written, informed consent to participation in the study.

Tissue preparation

Immediately after excision, lung tissue samples were placed in Krebs-Henseleit solution (mM: 120 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 15 NaHCO3, 1.2 KH2PO4, 11 D-glucose and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4) and immediately transported to our laboratory. After intralobar arteries had been carefully dissected free of parenchyma and adhering connective tissue, several rings (3 to 5 mm in length, and 1.5 to 2 mm in internal diameter) were prepared from a single artery. Some of the rings were used immediately for pharmacological studies, whereas others were snap-frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen for subsequent protein extraction.

Endothelial function was evaluated by the cumulative acetylcholine (Ach) dose response curve for pulmonary artery rings isolated from smokers or never-smokers. Under our experimental conditions, endothelial dysfunction was defined as an impaired response to Ach (such as a lack of relaxation, or even contraction).

The pharmacological experiments

Arterial rings were mounted in bath organs, as previously described [5]. Briefly, rings were suspended on tissue hooks in 5 ml organ baths containing Krebs-Henseleit solution at 37°C and bubbled with 95% O2 and 5% CO2. Each preparation was connected to a force displacement transducer (Statham UF-1) and changes in isometric tension were recorded. An initial tension of 1 g was applied to the rings, which were then left to equilibrate for 30 minutes (with regular changes in fresh Krebs-Henseleit solution) until a stable resting tension (RT1) was obtained. The rings’ responsiveness was confirmed by adding KCl (to 40 mM), which induced contraction. Viable rings were then washed until full relaxation had occurred (resting tension 2, RT2), and were left to rest for 20 minutes. The rings were then precontracted with L-phenylephrine (PE) dichloride (10−5 M) to obtain a stable plateau of contraction. Serial dilutions of Ach chloride were then added, in order to establish a cumulative dose response curve (10−10 to 10−4 M). Relaxation in response to Ach was expressed as a percentage of the contraction induced by PE. A contractile response to Ach was expressed as a negative value. Endothelium-independent relaxation was assessed by measuring the response to sodium nitroprusside 10−5 M at the end of each experiment.

For each patient, some rings were pre-treated with various drugs for 30 minutes after PE precontraction. To test the hypothesis whereby NOS lacked substrate, we supplemented the rings with L-arg (10−3 M). To evaluate the role of arginases in pulmonary vasoactivity, we assessed the effects of the arginase antagonist N(omega)-hydroxy-nor-l-arginine (NorNOHA; 10−5 M). Lastly, we tested the effect of the NO potentiator genistein (10−6 M). The concentrations of these drugs producing 50% of the maximum effect were determined in preliminary experiments (data not shown).

All drugs were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), with the exception of Ach (provided by Pharmacie Centrale des Hôpitaux, Paris, France).

All experiments were performed in duplicate. The inter-ring variability was always below 10%.

Western blot analyses

Nitric oxide synthase 3 and arginases 1 and 2 were assayed in homogenized extracts of pulmonary arteries, as previously described [5]. Total proteins were extracted with a lysis buffer (10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 50 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, and 20% antiprotease cocktail) and were measured with a bicinchoninic acid protein assay kit (Pierce) on a microplate, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total proteins (30 μg/lane) were separated by electrophoresis on a 10% sodium dodecyl sulphate–polyacrylamide gel, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes and immunodetected. Nonspecific binding was blocked by incubation with 10% milk powder in Tris-buffered saline for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were incubated with a rabbit polyclonal antibody against NOS3 (sc-654, 1:150 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX) or goat polyclonal antibodies against arginases I or II (sc-18351 and sc 18360, 1:200 dilution, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) followed by biotinylated secondary antibodies: anti-rabbit IgG peroxidase conjugate (sc-2004, 1:1,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or anti-goat IgG peroxidase conjugate (sc-2922, 1:1,000 dilution; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Membranes were subsequently stripped and reprobed with a mouse monoclonal antibody against β-actin (AANO2; dilution: 1:1,000; Cytoskeleton, Inc., Denver, CO). The proteins were detected with an enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) kit and high-performance chemiluminescence film (GE Healthcare, Aulnay sous Bois, France). The intensities of protein staining on the immunoreactive Western blot bands were analyzed with ImageJ image analysis software. The relative amounts of immunoreactive proteins were calculated by dividing the scanning unit value by the respective value of β-actin protein (probed with the primary anti-β-actin antibody) and expressed in arbitrary units.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), except where otherwise specified. Data were analysed with NCSS9 (NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, UT) and GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) For intergroup comparisons, a non-parametric analysis of variance (ANOVA) was followed by Dunn’s test for multiple comparisons. For comparisons of condition (i.e. Ach dose–response curves in the presence and absence of another drug), a repeated measures ANOVA was followed by a Tukey-Kramer test for multiple comparisons. Fischer’s exact test or Mann–Whitney test was used for categorical variables. A p value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Subjects

Explants were obtained from 29 current smokers/ex-smokers and 10 never-smokers. Smoking history was the only demographic or clinical factor that differed significantly when comparing smokers and never-smokers (Table 1).

Tobacco smoking impairs the relaxant response of the pulmonary artery

The vasodilatory response to Ach was strongly altered in smokers, when compared with never-smokers (10 ± 7% vs. 42 ± 8% at 10−4 M Ach, respectively, p < 0.01, Figure 1, panel A). Closer analysis of responses of the rings from the smokers enabled us to distinguish between two subgroups: 11 patients exhibited endothelial dysfunction as defined above (the ED+ subgroup), whereas the remaining 18 exhibited a relaxant response (forming the ED− subgroup) similar to that seen in never-smokers (−23 ± 10% vs. 31 ± 4% and 42 ± 8% at 10−4 M Ach in the ED+ subgroup, the ED− subgroup and never-smokers, respectively; p < 0.01, Figure 1, panel B). The ED+ vs. ED− subgroups did not differ significantly in terms of baseline tensions or peak vasoconstriction in response to PE (RT1: 0.9 ± 0.1 g vs. 0.9 ± 0.1 g (ns), respectively; RT2: 0.8 ± 0.1 g vs. 0.9 ± 0.1 g (ns), respectively; PE-induced tension: 1.2 ± 0.2 g vs. 1.4 ± 0.1 g, respectively; data not shown). SNP 10−5 M induced a relaxant response in all patients, including those with an endothelial dysfunction, discarding the fact that the lack of endothelium-dependant response could be due to the damage of the pulmonary artery during its manipulation (data not shown). In neither subgroup was the response to Ach correlated with age, gender, cumulative tobacco smoking, COPD, forced expiratory flow in 1 second (FEV1), systolic pulmonary artery pressure (as measured by echocardiography, when available) or other possible confounders of endothelial dysfunction, such as hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, ongoing treatment with statins or vasodilators, diabetes mellitus, and prior treatment with cytotoxic drugs (Table 2).

Pulmonary endothelial function, represented as cumulative Ach dose response curves in pulmonary artery rings from smokers (n = 29) and never-smokers (n = 10). Smokers had impaired relaxation in response to Ach, when compared with never-smokers (p < 0.01; panel A). The smokers were divided into two subgroups according to the presence (ED+, n = 11) or absence (ED−, n = 18) of pulmonary endothelial dysfunction (p < 0.01; panel B).

All of the 11 ED+ patients had undergone pre-operative echocardiography and none had displayed an elevated systolic pulmonary artery pressure at rest.

L-arginine supplementation improves endothelium-dependent function

To investigate whether endothelial dysfunction could be explained by a lack of the NOS substrate L-arg, we measured the ED+ samples’ Ach dose–response curves in the presence and absence of substrate supplementation (n = 6). Supplementation with L-arg (10−3 M) significantly improved endothelial function but did not restore a normal vasodilatory response (−4 ± 10% vs. -32 ± 10% at 10−4 M Ach in the presence and absence of L-arg, respectively; p = 0.006; Figure 2).

Arginase inhibition restores endothelium-dependent dilation

We tested the effect of the arginase inhibitor NorNOHA (10−5 M) on the ED+ samples’ response to Ach (n = 4). Arginase inhibition significantly improved endothelial function and restored the relaxant response to Ach (18 ± 9% vs. -1 ± 9% at 10−4 M Ach in the presence and absence of NorNOHA, respectively; p = 0.0002; Figure 3).

Effect of genistein on endothelial dysfunction

The phytoestrogen genistein can potentially enhance NO production by activating NOS3. We sought to determine whether the compound could improve the vasodilatory response in ED+ subjects (n = 4). Genistein (10−6 M) did not improve this response (−13 ± 7% vs. -14 ± 3% at 10−4 M Ach in the presence and absence of genistein, respectively, NS) (Figure 4).

NOS and arginase expression

In pulmonary artery samples analysed with Western blotting, arginase I protein expression was significantly higher in ED+ patients (n = 3) than in ED− patients (n = 4) (mean relative expression: 2.45 ± 0.15 vs. 1.19 ± 0.25, respectively; p < 0.05; Figure 5, panel A). In contrast, levels of arginase II expression were similar the ED+ (n = 4) and ED− subgroups (n = 4) (Figure 5, panel B). Likewise, the ED+ and ED− subgroups did not differ significantly in terms of the expression of NOS3 in pulmonary artery rings (mean relative expression: 1.34 ± 0.2 vs. 1.76 ± 1.2, respectively, NS) (Figure 6).

Protein expression of arginases I and II in pulmonary artery samples from ED + and ED − patients. Arginase I protein expression (as analysed by Western blotting) was higher in ED+ patients (n = 3) than in ED- patients (n = 4), p<0.05; panel A. Arginase II protein expression was similar in ED+ (n = 4) and ED− patients (n = 4); panel B. The vertical line indicates that the gel was cut.

Discussion

We found that the impairment in pulmonary vasodilation observed in a significant proportion of smokers may be explained by increased arginase I protein expression in the pulmonary artery. L-arg supplementation reduced the endothelial dysfunction, and arginase inhibition restored a normal vasodilatory, endothelium-dependent response in ED+ patients. Lastly, we confirmed our previous report of the high prevalence of pulmonary endothelial dysfunction in smokers (38% in the present study) [5], even in those with normal lung function. Indeed, our smokers and nonsmokers were quite similar in terms of clinical characteristics (and cardiovascular risk factors in particular), and there were only two smokers in the study population with overt, moderate COPD, Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) stage 2. The other smokers had normal lung function. Taken as a whole, our present data strengthen the general hypothesis whereby tobacco smoking has a direct, harmful influence on the pulmonary vasculature.

In terms of putative mechanisms, our study focused on the NO pathway because changes in NO bioavailability are thought to have a major role in endothelial dysfunction [6]. Nitric oxide acts as an endothelial central signalling molecule [24] that controls vascular tone and structure by decreasing vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation [25,26]. A decreased NO bioavailability, as we hypothesize in smokers exhibiting an abnormal vasorelaxation (ED+ subjects) might partly result from a limitation in substrate [6,21,15]. Indeed, arginase and NOS compete for their common substrate, L-arginine, and an overactive arginase might limit substrate availability for NOS and therefore NO production. In addition, an increased oxidative stress might also partly account for the vascular dysfunction showed in this study. Our experiments revealed that NO bioavailability was impaired in ED+ subjects as a result of absolute and relative substrate deficiencies. Indeed, the arginase inhibitor NorNOHA was able to partly restore a relaxant response, suggesting that ED+ subjects have elevated arginase activity. This can be explained by the elevated vascular arginase I protein expression observed in ED+ samples. Taken as a whole, these results suggest that NO production by NOS3 is limited by competition with arginase I for the common substrate L-arg, which ultimately leads to a relative substrate deficiency. Enhanced arginase activity has been associated with the systemic endothelial dysfunction observed in various conditions. Some cell-based and preclinical studies using arginase inhibitors have provided convincing evidence for arginase’s harmful effects in cardiovascular diseases [15,18] in which arginase expression is upregulated [17,27]. Although data for the pulmonary circulation are scarce, harmful effects of arginase upregulation and/or of low L-arg levels have also been demonstrated in models of primary or secondary PH [22,28-32]. To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to have demonstrated the role of increased arginase activity in tobacco associated-pulmonary endothelial dysfunction. Increased arginase activity has also been associated with airway hyperresponsiveness [33,34]; we previously demonstrated that increased arginase activity is involved in airway sensitivity in smokers [35]. Overall, elevated arginase activity may be one of the mechanisms underlying both pulmonary arterial dysfunction and bronchial dysfunction [36].

Studies with L-arg supplementation have shown inconsistent effects on both systemic and pulmonary endothelial functions [37-39]. In the present study, L-arg supplementation reduced the dysfunction in ED+ patients but did not restore a normal vasodilatory response; this finding suggests an absolute lack of substrate in these individuals. The lack of complete restoration of a normal vasodilatory response might involve (amongst others) additional mediators of pulmonary tobacco associated- endothelial dysfunction, such as increased activation of the endothelin (ET)-1/ET-A pathway (as we have previously reported [5]). In line with the recent literature, the ED+ and ED− subgroups did not differ significantly in terms of expression of NOS3 (the arginases’ competitor for NO production) in the pulmonary vasculature [40]. The exact relationship between cigarette smoke and NOS3 expression/activity is still subject to debate. In animal studies, smoke exposure has variously led to a decrease or an increase in NOS3 expression [41-43]. Given that NOS3 is tightly regulated by post-translational lipid modifications, protein-protein interactions and protein phosphorylation [44], its protein expression levels are not correlated with its activity. The fact that genistein (a strong potentiator of NO production via NOS3 activation) did not enhance vasorelaxation in ED+ subjects suggests that impaired NOS3 activity does not have a role in endothelial dysfunction in that context.

Conclusions

Arginase I overexpression and activity may be involved in tobacco-induced pulmonary endothelial dysfunction. The present results are of interest because they suggest that increased arginase activity may be one of the mechanisms underlying both pulmonary arterial dysfunction and bronchial dysfunction. Further research must explore the effects of combined L-arg supplementation and arginase inhibition and assess the potential value of these approaches in resolving endothelial dysfunction in the setting of tobacco exposure.

Abbreviations

- Ach:

-

Acetylcholine

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- NO:

-

Nitric oxide

- NOS:

-

Nitric oxide synthase

- L-arg:

-

L-arginine

- NorNOHA:

-

N-hydroxy-nor-L-arginine

- ED+ :

-

Subgroup with endothelial dysfunction

- ED− :

-

Subgroup without endothelial dysfunction

- FEV1:

-

Forced expiratory flow in 1 second

- GOLD:

-

Global initiative for obstructive lung disease

References

Santos S, Peinado VI, Ramírez J, Melgosa T, Roca J, Rodriguez-Roisin R, et al. Characterization of pulmonary vascular remodelling in smokers and patients with mild COPD. Eur Respir J. 2002;19(4):632–8.

Voelkel NF, Cool CD. Pulmonary vascular involvement in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J Suppl. 2003;46:28s–32.

Hoeper MM, Barberà JA, Channick RN, Hassoun PM, Lang IM, Manes A, et al. Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment of non-pulmonary arterial hypertension pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(1 Suppl):S85–96.

Dinh-Xuan AT, Higenbottam TW, Clelland CA, Pepke-Zaba J, Cremona G, Butt AY, et al. Impairment of endothelium-dependent pulmonary-artery relaxation in chronic obstructive lung disease. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(22):1539–47.

Henno P, Boitiaux JF, Douvry B, Cazes A, Lévy M, Devillier P, et al. Tobacco-associated pulmonary vascular dysfunction in smokers: role of the ET-1 pathway. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300(6):L831–9.

Munzel T, Heitzer T, Harrison DG. The physiology and pathophysiology of the nitric oxide/superoxide system. Herz. 1997;22(3):158–72.

Durante W, Liao L, Reyna SV, Peyton KJ, Schafer AI. Physiological cyclic stretch directs L-arginine transport and metabolism to collagen synthesis in vascular smooth muscle. FASEB J. 2000;14(12):1775–83.

Harrison DG. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of endothelial cell dysfunction. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(9):2153–7.

Hacker AD. Inhibition of deoxyribonucleic acid synthesis by difluoromethylornithine. Role of polyamine metabolism in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary hypertension. Biochem Pharmacol. 1992;44(5):965–71.

Ignarro LJ, Buga GM, Wei LH, Bauer PM, Wu G, del Soldato P. Role of the arginine-nitric oxide pathway in the regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98(7):4202–8.

Beleznai T, Feher A, Spielvogel D, Lansman SL, Bagi Z. Arginase 1 contributes to diminished coronary arteriolar dilation in patients with diabetes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300(3):H777–83.

Gonon AT, Jung C, Katz A, Westerblad H, Shemyakin A, Sjöquist PO, et al. Local arginase inhibition during early reperfusion mediates cardioprotection via increased nitric oxide production. PLoS One. 2012;7(7):e42038.

Holowatz LA, Kenney WL. Up-regulation of arginase activity contributes to attenuated reflex cutaneous vasodilatation in hypertensive humans. J Physiol. 2007;581(Pt 2):863–72.

Holowatz LA, Thompson CS, Kenney WL. L-Arginine supplementation or arginase inhibition augments reflex cutaneous vasodilatation in aged human skin. J Physiol. 2006;574(Pt 2):573–81.

Pernow J, Jung C. Arginase as a potential target in the treatment of cardiovascular disease: reversal of arginine steal? Cardiovasc Res. 2013;98(3):334–43.

Quitter F, Figulla HR, Ferrari M, Pernow J, Jung C. Increased arginase levels in heart failure represent a therapeutic target to rescue microvascular perfusion. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc. 2013;54(1):75–85.

Ryoo S, Gupta G, Benjo A, Lim HK, Camara A, Sikka G, et al. Endothelial arginase II: a novel target for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2008;102(8):923–32.

Shemyakin A, Kövamees O, Rafnsson A, Böhm F, Svenarud P, Settergren M, et al. Arginase inhibition improves endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2012;126(25):2943–50.

Nagai A, Imamura M, Watanabe T, Azuma H. Involvement of altered arginase activity, arginase I expression and NO production in accelerated intimal hyperplasia following cigarette smoke extract. Life Sci. 2008;83(13–14):453–9.

Pera T, Zuidhof AB, Smit M, Menzen MH, Klein T, Flik G, et al. Arginase inhibition prevents inflammation and remodeling in a guinea pig model of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2014;349(2):229–38.

Sikka G, Pandey D, Bhuniya AK, Steppan J, Armstrong D, Santhanam L, et al. Contribution of arginase activation to vascular dysfunction in cigarette smoking. Atherosclerosis. 2013;231(1):91–4.

Watts JA, Gellar MA, Fulkerson MB, Das SK, Kline JA. Arginase depletes plasma l-arginine and decreases pulmonary vascular reserve during experimental pulmonary embolism. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2012;25(1):48–54.

Watts JA, Marchick MR, Gellar MA, Kline JA. Up-regulation of arginase II contributes to pulmonary vascular endothelial cell dysfunction during experimental pulmonary embolism. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24(4):407–13.

Ignarro LJ, Cirino G, Casini A, Napoli C. Nitric oxide as a signaling molecule in the vascular system: an overview. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 1999;34(6):879–86.

Chen C, Hanson SR, Keefer LK, Saavedra JE, Davies KM, Hutsell TC, et al. Boundary layer infusion of nitric oxide reduces early smooth muscle cell proliferation in the endarterectomized canine artery. J Surg Res. 1997;67(1):26–32.

Seki J, Nishio M, Kato Y, Motoyama Y, Yoshida K. FK409, a new nitric-oxide donor, suppresses smooth muscle proliferation in the rat model of balloon angioplasty. Atherosclerosis. 1995;117(1):97–106.

Santhanam L, Lim HK, Lim HK, Miriel V, Brown T, Patel M, et al. Inducible NO synthase dependent S-nitrosylation and activation of arginase1 contribute to age-related endothelial dysfunction. Circ Res. 2007;101(7):692–702.

Morris CR, Kato GJ, Poljakovic M, Wang X, Blackwelder WC, Sachdev V, et al. Dysregulated arginine metabolism, hemolysis-associated pulmonary hypertension, and mortality in sickle cell disease. JAMA. 2005;294(1):81–90.

Morris CR, Morris Jr SM, Hagar W, Van Warmerdam J, Claster S, Kepka-Lenhart D, et al. Arginine therapy: a new treatment for pulmonary hypertension in sickle cell disease? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(1):63–9.

Sasaki A, Doi S, Mizutani S, Azuma H. Roles of accumulated endogenous nitric oxide synthase inhibitors, enhanced arginase activity, and attenuated nitric oxide synthase activity in endothelial cells for pulmonary hypertension in rats. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2007;292(6):L1480–7.

Xu W, Kaneko FT, Zheng S, Comhair SA, Janocha AJ, Goggans T, et al. Increased arginase II and decreased NO synthesis in endothelial cells of patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. FASEB J. 2004;18(14):1746–8.

Krotova K, Patel JM, Block ER, Zharikov S. Hypoxic upregulation of Arginase Ii in human lung endothelial cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2010;299(6):C1541–8.

Mabalirajan U, Ahmad T, Leishangthem GD, Joseph DA, Dinda AK, Agrawal A, et al. Beneficial effects of high dose of L-arginine on airway hyperresponsiveness and airway inflammation in a murine model of asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(3):626–35.

Meurs H, McKay S, Maarsingh H, Hamer MA, Macic L, Molendijk N. Increased arginase activity underlies allergen-induced deficiency of cNOS-derived nitric oxide and airway hyperresponsiveness. Br J Pharmacol. 2002;136(3):391–8.

Tadie JM, Henno P, Leroy I, Danel C, Naline E, Faisy C, et al. Role of nitric oxide synthase/arginase balance in bronchial reactivity in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2008;294(3):L489–97.

Oualha M, Boitiaux JF, Tadié JM, Cazes A, Riquet M, Naline E, et al. Association of ex vivo vascular and bronchial dysfunctions in smokers. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2011;24(2):227–31.

Jahangir E, Vita JA, Handy D, Holbrook M, Palmisano J, Beal R, et al. The effect of L-arginine and creatine on vascular function and homocysteine metabolism. Vasc Med. 2009;14(3):239–48.

Lucotti P, Monti L, Setola E, La Canna G, Castiglioni A, Rossodivita A, et al. Oral L-arginine supplementation improves endothelial function and ameliorates insulin sensitivity and inflammation in cardiopathic nondiabetic patients after an aortocoronary bypass. Metabolism. 2009;58(9):1270–6.

Hutchison SJ, Sievers RE, Zhu BQ, Sun YP, Stewart DJ, Parmley WW, et al. Secondhand tobacco smoke impairs rabbit pulmonary artery endothelium-dependent relaxation. Chest. 2001;120(6):2004–12.

Brindicci C, Kharitonov SA, Ito M, Elliott MW, Hogg JC, Barnes PJ, et al. Nitric oxide synthase isoenzyme expression and activity in peripheral lung tissue of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(1):21–30.

Tuder RM, Wood K, Taraseviciene L, Flores SC, Voekel NF. Cigarette smoke extract decreases the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor by cultured cells and triggers apoptosis of pulmonary endothelial cells. Chest. 2000;117(5 Suppl 1):241S–2.

Wright JL, Dai J, Zay K, Price K, Gilks CB, Churg A. Effects of cigarette smoke on nitric oxide synthase expression in the rat lung. Lab Invest. 1999;79(8):975–83.

Wright JL, Tai H, Churg A. Vasoactive mediators and pulmonary hypertension after cigarette smoke exposure in the guinea pig. J Appl Physiol. 2006;100(2):672–8.

Sessa WC. eNOS at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2004;117(Pt 12):2427–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr David Fraser (Biotech Communication SARL, Damery, France) for editorial assistance.

P. Henno receiving funding from the Société de Pneumologie de Langue Française.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

PH carried out the pharmacological and Western blotting studies, performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. CM participated in the pharmacological and Western blotting studies. FLPB provided surgical specimens and revised the manuscript. PD participated in the data analysis and revised the manuscript. CD conceived and designed the study and revised the manuscript. DIB participated in the design of the study, coordinated it and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Henno, P., Maurey, C., Le Pimpec-Barthes, F. et al. Is arginase a potential drug target in tobacco-induced pulmonary endothelial dysfunction?. Respir Res 16, 46 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0196-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12931-015-0196-4