Abstract

Background

The mitochondrial 12S rRNA A1555G mutation is the most prevalent deafness-causing mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutation and is inherited maternally. Studies have suggested that A1555G mutations have multiple origins, although there is no direct evidence of this. Here, we identified a family with a de novo A1555G mutation.

Method

Based on detailed mtDNA analyses of the family members using next-generation sequencing with 1% sensitivity to mutated mtDNA, the level of heteroplasmy in terms of the A1555G mutation in blood DNA samples was quantified.

Results

An individual harbored a heterogeneous A1555G mutation, at 28.68% heteroplasmy. The individual’s son was also a heterogeneous carrier, with 7.25% heteroplasmy. The individual’s brother and mother did not carry the A1555G mutation, and both had less than 1% mitochondrial 12S rRNA A1555G heteroplasmy.

Conclusion

The A1555G mutation arose de novo in this family. This is the first report of a family with a de novo A1555G mutation, providing direct evidence of its multipoint origin. This is important for both diagnostic investigations and genetic counselling.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Deafness is a common health problem, affecting approximately 1 in 1000 newborns worldwide [1]. Hearing loss can be caused by genetic and environmental factors. Approximately 60% of congenital hearing impairment cases have a genetic cause, with autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked, and mitochondrial patterns of inheritance [2]. Mutations in the GJB2, mitochondrial 12S rRNA, and SLC26A4 genes play important roles in hearing loss. More than 200 point mutations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) have been reported in the mtDNA mutation database MITOMAP. Since the deafness caused by A1555G mutation in the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene was first reported by Prezant et al. in 1993, many mitochondrial 12S rRNA A1555G mutant families associated with aminoglycoside induced deafness and maternally inherited nonsyndromic deafness have been reported all over the world, with its prevalences of 2.4% in European sensorineural deafness patients and 3.2% in Chinese sensorineural deafness patients [3,4,5]. The A1555G mtDNA mutation in the 12S rRNA gene is the third most common deafness-causing mutation in the Chinese population [3].

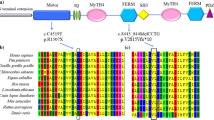

The A1555G mutation is located in the aminoacyl-tRNA acceptor site of the small ribosomal subunit, which is highly conserved from bacteria to mammals [6]. Little is known about the incidence of de novo A1555G mutations. Here, we report an individual with a de novo heterogeneous A1555G mutation in 12S rRNA who presented with normal hearing. This provides direct evidence of the multipoint origin of the A1555G mutation.

Materials and methods

Patients

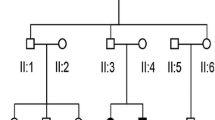

We reviewed the genetic characteristics of families possessing the A1555G mutation in the database of the Genetic Testing Center for Deafness (PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China) and found a family (Family 2362) that did not fully conform to the maternal genetic characteristics (Fig. 1). As controls, 200 individuals negative for GJB2, SLC26A4, and mtDNA 12S rRNA mutations were recruited, including 100 individuals with normal hearing (Group 1) and 100 patients with sensorineural hearing loss (Group 2).

Each participant underwent a comprehensive clinical history and physical examination. Audiological examinations were performed, including pure-tone audiometry and auditory brainstem responses.

Paternity testing

Paternity was tested for three generations (I:1, II:1, II:2, and III:2) using genotype analysis of 15 informative chromosome short tandem repeats (STRs).

Mutation analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from the peripheral blood of subjects using a blood DNA extraction kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Tiangen, Beijing, China). All family members were screened for common deafness genes, including GJB2, SLC26A4, and mtDNA 12S rRNA, using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification, and the exons were sequenced directly [7]. For quantitative analysis of the mutation frequency at nucleotide 1555 in the control group and members of Family 2362, capture and next-generation sequencing (NGS) of a 147-bp DNA fragment corresponding to positions 1466–1612 of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene was performed on the Ion Proton System.

Results

Deafness gene testing

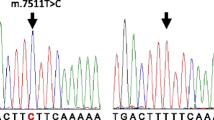

Family 2362 is a three-generation Chinese family, in which one member has severe sensorineural hearing loss (Fig. 1). To clarify the cause of deafness in this family member, we searched for the gene responsible for the deafness in the proband and her parents. The proband (III:1) had a compound heterozygous mutation in GJB2 (c.176del16 and c.299delAT); the mother (II:3) carried the c.176del16 mutation, the father (II:1) carried the c.299delAT mutation, and all three(II:1, II:3, III:1) lacked the A1555G mutation. To identify carriers of the c.299delAT mutation, family member II:2 with normal hearing was also tested for deafness genes. II:2 did not carry the c.299delAT mutation but had an A1555G heteroplasmic mutation in the mitochondrial gene, detected by Sanger sequencing. Further tests revealed that III:2 also carried the A1555G heteroplasmic mutation, whereas I:1 lacked this mutation (Figs. 1, 2). Therefore, this study focused on the maternal lineage I:1, II:2, II:3, and III:2 to clarify the status of the A1555G mutation.

Paternity testing

The paternity of the three generations (I:1, II:1, II:2, and III:2) was confirmed by genotype analysis of 15 informative STRs of chromosomal DNA, which yielded probabilities of paternity of 0.999999, assuming a prior probability of 0.50. Therefore, the family members were all related.

Quantitative analysis of the A1555G mutation

Targeted NGS showed that the subject (II:2) carried a heterogeneous A1555G mutation, at 28.68% heteroplasmy. The son of II:2 (III:2) was also a heterogeneous mutation carrier, with a level of heteroplasmy of 7.25%. The brother (II:1) and mother (I:1) of II:2 had 0.23% and 0.03% A1555G heteroplasmy, respectively (Table 1).

The level of mitochondrial 12S rRNA A1555G heteroplasmy in all 100 controls with normal hearing (Group 1) and in 100 patients with severe sensorineural hearing loss (Group 2) was less than 1% and did not differ significantly between these two control groups (P > 0.05; Table 2).

Discussion

The mitochondrial 12S rRNA A1555G mutation is a hot spot for deafness-associated mutations in the Chinese population [8]. This mutation has been detected in up to 60% of hearing-impaired patients with previous exposure to aminoglycosides and in 0.09–0.70% of the general population [9, 10]. The incidence of this mutation is much lower in nonsyndromic hearing loss than in aminoglycoside-induced hearing impairment. In a Chinese pediatric population, Lu et al. reported that the incidence of the A1555G mutation was 1.43% in nonsyndromic hearing loss and 10.41% in aminoglycoside-induced hearing loss [11]. Although the contribution of the mtDNA A1555G mutation to congenital (prelingual, early childhood onset) deafness is minor, mitochondrial involvement is seen in patients with postlingual hearing impairment, a much larger population.

There is no treatment for mitochondrial hearing impairment, suggesting that testing for the mutation should be performed routinely before administering aminoglycoside antibiotics. Detection of the A1555G mutation is an important part of deafness gene screening. Sanger sequencing was long the gold standard for identifying unknown mtDNA point mutations before the advent of massively parallel sequencing analysis. However, the conventional Sanger sequencing does not have the sensitivity to detect heteroplasmic mutations below about 20%. NGS technologies have the capability of massively parallel sequencing and offer a robust platform for comprehensive analysis of mtDNA [12]. The small size of the mitochondrial genome resulting in high coverage at each nucleotide position enable more rapid, sensitive, and accurate quantification of low-level heteroplasmy. NGS is a powerful tool for detecting low-level heteroplasmy variants in the mitochondrial genome, which has greatly improved the ability to distinguish carriers from non-carriers. The sensitive detection and accurate quantification of pathogenic heteroplasmic changes are helpful for risk prediction and genetic counseling.

In our study, targeted NGS showed that subject II:2 is a heterogeneous carrier of the mitochondrial 12S rRNA A1555G mutation at a level of 28.68% heteroplasmy. The son of II:2 (III:2) is also a heterogeneous mutation carrier at a level of 7.25% heteroplasmy. The brother (II:1) and mother (I:1) had 0.23% and 0.03% A1555G heteroplasmy. The level of mitochondrial 12S rRNA A1555G heteroplasmy tested by NGS in the 100 cases with normal hearing and 100 patients with severe sensorineural hearing loss negative for GJB2, SLC26A4, and mtDNA 12S rRNA was less than 1% and did not differ significantly (P > 0.05) between these two groups.

The presence of the mtDNA mutation in subject II:2 but not in her mother has three possible explanations: (1) other family members in the maternal lineage harbor the mutation, but at levels below the detection limit; (2) there is no biological relationship between subject II:2 and other family members tested; or (3) a de novo mutation occurred. We investigated all three possibilities.

To investigate the possibility that the mutation is present at a level below the sensitivity of the sequencing method, we sequenced the mtDNA at an average depth of 5000 × using NGS technology. The Ion Proton sequencing platform is sensitive enough to detect point mutations present with heteroplasmy levels as low as 1%. In the control groups, the level of mitochondrial 12S rRNA A1555G heteroplasmy was less than 1%, confirming the accuracy of this method. The probability of multiple false-negative results in the brother (II:1) and mother (I:1) is very low. Therefore, it is unlikely that other family members in the maternal lineage also carry the mutation at heteroplasmy levels below the detection limit.

To investigate non-kinship as the potential cause, we confirmed kinship from the mothers within the family. The paternity of the three generations (I:1, II:1, II:2, and III:2) was confirmed by genotype analysis of 15 informative STRs, yielding a probability of paternity of 0.999999, assuming a prior probability of 0.50. Having excluded kinship and sensitivity issues, we conclude that the A1555G mutation most likely appeared de novo in the family.

The A1555G mutation has been detected in patients with different haplotypes, indicating that de novo appearance of the A1555G mutation has occurred frequently in the past. MtDNA is solely inherited maternally and does not recombine, consequently, mutations accumulate in maternal lineages. According to most literature reports, mitochondria have relatively less sophisticated DNA protection and repair systems and high mutation rates [13]. But there are very few reports about de novo mutation in mitochondria, so the frequency of de novo mutation in mitochondria is not clear. In our previous study, we found that among 193 families carrying mitochondrial A1555G mutation, only one family had de novo mutation. So the frequency of de novo mutation in mitochondrial A1555G is 0.52% based on our data. Although the mechanism behind the de novo appearance of the A1555G mutation is unknown, we speculate that the mutation likely occurred during oogenesis (during embryonic development of the mother) or during early embryonic development of subject II:2.

There has been considerable debate about whether paternal mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) transmission may coexist with maternal transmission of mtDNA, it is generally believed that mitochondria and mtDNA are exclusively maternally inherited in humans. This study did not verify the mitochondrial genetic maternal model. In the future research, we will supplement this part of work. In Fig. 1, we show the genetic relationship between I:1/II:2 and II:2/III:2 according to the law of maternal inheritance.

The observation of a de novo A1555G mutation is relevant for both diagnostic investigations and genetic counselling. First, even when there is no (maternal) family history in patients with deafness, A1555G mutation screening should still be performed to identify the cause of the disease. Second, screening in maternally related family members is recommended to provide reliable counselling for these families, given that the A1555G mutation may have arisen de novo. A genetic diagnosis of the A1555G mutation in an isolated patient does not necessarily mean that others in the maternal lineage also harbor the mutation. Although the vast majority of A1555G mutations are inherited maternally, a thorough family investigation should always be performed. Genetic counselling for deafness caused by the A1555G mutation is complicated. In individuals treated with aminoglycosides and thus at risk of hearing loss, mtDNA analysis can help predict hearing loss and the need to take precautions before symptom onset, as well as enable more accurate genetic counseling.

Conclusion

We identified a family in whom the A1555G mutation appears to have arisen de novo. This has importance for both diagnosing and counselling patients. Determining if a mutation is inherited or de novo affects counseling regarding the risk of recurrence. This is the first report of a family with a de novo A1555G mutation, and it provides additional information on the origin and inheritance of the A1555G mutation.

Availability of data and materials

All data and material are available on the database of the Genetic Testing Center for Deafness (PLA General Hospital, Beijing, China).The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in https://dataview.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, accession number: PRJNA830478.

Abbreviations

- mtDNA:

-

Mitochondrial DNA

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- STRs:

-

Short tandem repeats

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

Jiang H, Chen J, Li Y, Lin PF, He JG, Yang BB. Prevalence of mitochondrial DNA mutations in sporadic patients with nonsyndromic sensorineural hearing loss. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2016;82:391–6.

Xing J, Liu X, Tian Y, Tan J, Zhao H. Genetic and clinical analysis of nonsyndromic hearing impairment in pediatric and adult cases. Balkan J Med Genet. 2016;19:35–42.

Du W, Wang Q, Zhu Y, Wang Y, Guo Y. Associations between GJB2, mitochondrial 12S rRNA, SLC26A4 mutations, and hearing loss among three ethnicities. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:746838.

Guaran V, Astolfi L, Castiglione A, Simoni E, Olivetto E, Galasso M, et al. Association between idiopathic hearing loss and mitochondrial DNA mutations: a study on 169 hearing-impaired subjects. Int J Mol Med. 2013;32:785–94.

Lu J, Qian Y, Li Z, Yang A, Zhu Y, Li R, et al. Mitochondrial haplotypes may modulate the phenotypic manifestation of the deafness-associated 12S rRNA 1555A>G mutation. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:69–81.

Ruiz-Pesini E, Wallace DC. Evidence for adaptive selection acting on the tRNA and rRNA genes of human mitochondrial DNA. Hum Mutat. 2006;27:1072–81.

Zhao H, Li R, Wang Q, Yan Q, Deng JH, Han D, et al. Maternally inherited aminoglycoside-induced and nonsyndromic deafness is associated with the novel C1494T mutation in the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene in a large Chinese family. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:139–52.

Zhu Y, Zhao J, Feng B, Su Y, Kang D, Yuan H, et al. Mutations in the mitochondrial 12S rRNA gene in elderly Chinese people. Acta Otolaryngol. 2015;135:26–34.

Liu XZ, Angeli S, Ouyang XM, Liu W, Ke XM, Liu YH, et al. Audiological and genetic features of the mtDNA mutations. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:732–8.

Skou AS, Tranebjaerg L, Jensen T, Hasle H. Mitochondrial 12S ribosomal RNA A1555G mutation associated with cardiomyopathy and hearing loss following high-dose chemotherapy and repeated aminoglycoside exposure. J Pediatr. 2014;164:413–5.

Lu J, Li Z, Zhu Y, Yang A, Li R, Zheng J, et al. Mitochondrial 12S rRNA variants in 1642 Han Chinese pediatric subjects with aminoglycoside-induced and nonsyndromic hearing loss. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:380–90.

Wong LJ. Next generation molecular diagnosis of mitochondrial disorders. Mitochondrion. 2013;13:379–87.

Ding Y, Leng J, Fan F, Xia B, Xu P. The role of mitochondrial DNA mutations in hearing loss. Biochem Genet. 2013;51:588–602.

Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank all the family members for their participation and cooperation in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81870731, 81730029, 81873704, 81570929, 61827805 and 81900953), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (7191011, 7192234).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PG, SH, and PD conceived the study, participated in its design, and drafted the manuscript. GW and XG participated in the data analysis. DK participated in the collection of clinical data and blood samples. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Chinese PLA General Hospital (Beijing, China) and conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all participants or from the guardians of subjects under 18 years of age.

Consent for publication

All enrolled patients released a consent to publish from the participant (or legal parent or guardian for children) to report individual patient data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Gu, P., Wang, G., Gao, X. et al. Clinical and molecular findings in a Chinese family with a de novo mitochondrial A1555G mutation. BMC Med Genomics 15, 121 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-022-01276-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-022-01276-y