Abstract

Background

Dried blood spots (DBS) are a relatively inexpensive source of nucleic acids and are easy to collect, transport, and store in large-scale field surveys, especially in resource-limited settings. However, their performance in whole-genome sequencing (WGS) relative to that of venous blood DNA has not been analyzed for various downstream applications.

Methods

This study compares the WGS performance of DBS paired with venous blood samples collected from 12 subjects.

Results

Results of standard quality checks of coverage, base quality, and mapping quality were found to be near identical between DBS and venous blood. Concordance for single-nucleotide variants, insertions and deletions, and copy number variants was high between these two sample types. Additionally, downstream analyses typical of population-based studies were performed, such as mitochondrial heteroplasmy detection, haplotype analysis, mitochondrial copy number changes, and determination of telomere lengths. The absolute mitochondrial copy number values were higher for DBS than for venous blood, though the trend in sample-to-sample variation was similar between DBS and blood. Telomere length estimates in most DBS samples were on par with those from venous blood.

Conclusion

DBS samples can serve as a robust and feasible alternative to venous blood for studies requiring WGS analysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Dried blood spots (DBS) have been used in population-based studies for years to quantify biomarkers and screen for infectious diseases and inherited metabolic disorders in newborns [1,2,3,4]. However, because the number of extractable biomolecules is small in DBS, the suitability of this sample type for generating high-quality data for genomic analysis is often debated. While published data from DBS samples using targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) are available, data from whole-genome sequencing (WGS) are sparse [5, 6].

Most population studies that involve WGS use venous blood (referred to as “blood” hereafter). However, collecting, transporting, and storing blood in field settings present challenges. A trained phlebotomist must collect blood samples in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) tubes, which are then shipped at a low temperature. These dependencies make blood collection expensive, cumbersome, and logistically unviable for large cohort studies, especially in resource-poor settings.

Given that DBS is inexpensive, scalable, easy to handle in the field and does not require a trained professional for collection [7, 8], we evaluated whether this sample type is suitable for WGS studies. To this end, we assessed the quantity and quality of DNA and WGS data of DBS samples with matched blood in a cohort of 12 subjects collected from the field. We matched the pairwise data for single-nucleotide variants (SNVs), insertions and deletions (InDels), and copy number variants (CNVs). In addition, we compared mitochondrial heteroplasmy variants and copy numbers and telomere lengths in these pairwise samples to evaluate the utility of DBS in population-based studies with end points such as haplogroup analysis, detection of heteroplasmy, and inheritance of mitochondrial diseases. Our results indicate that SNV/InDel concordance is high between DBS and blood, and telomere length estimates are similar between the two sample types. Mitochondrial copy number estimates were found to be matrix-specific, though the sample-to-sample differences were similar. Overall, we conclude that DBS is suitable for WGS analysis and can be used in population studies requiring field-collected samples.

Methods

Subjects and study design

Blood samples and matched dried blood spots were collected from 12 residents of Tumakuru district of Karnataka, India, after obtaining requisite permissions and consent. These subjects were chosen to ensure that the selected cohort had a comparable representation of males and females across different age groups (Table 1). The sample collection protocol was independently approved by the ethics committees at Strand Life Sciences and the Institute for Social and Economic Change. The samples were collected in a field setting and shipped to Strand’s laboratory for processing. All the methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Sample collection and storage

For DBS samples, drops of blood were collected from a needle prick and spotted onto circles on Whatman FTA cards (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). Three to four drops of blood were spotted per circle. The blood spots were air dried, packed, and then shipped to the lab at ambient temperature. DBS samples were stored at room temperature in a dry condition until DNA extraction. Blood samples (5 mL) were collected in K2-EDTA tubes. They were transported to the lab in cool packs (4 °C) within 12 h of collection and were stored at 4 °C until DNA was extracted.

DNA isolation

DNA was isolated from DBS samples within 40 days of collection using 6–7 punches of 2–3 mm diameter (two FTA card circles). Using the Formapure extraction and purification kit, DNA was manually extracted from pooled DBS punches. DNA was extracted from blood samples within 25 days of collection using the Agencourt Genfind v2 DNA isolation kit (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA), as recommended by the manufacturer, with the automated Biomek4000 (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA).

Library preparation and sequencing

WGS libraries were prepared using the Nextera DNA Flex Library Prep Kit (Illumina Inc., CA, USA). Input DNA of 100 ng was used for library preparation with minimal cycles of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) as recommended by the manufacturer. Adapter-tagged sequences were inserted into fragments of genomic DNA using bead-based transposons. Unique indices were added to each sample during PCR amplification. The PCR-amplified libraries were then purified and analyzed for size using TapeStation 2200 (Agilent Technologies, CA, USA). Normalized libraries were pooled and sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 system using the high-output 150 × 2 base pair S4 flow cell and reagents.

Bioinformatics quality control

All bioinformatics analyses were performed using Strand NGS ver. 3.3 (Strand Life Sciences, Bangalore, India). Raw reads were mapped to the human genome reference hg19. Distributions of base quality, read quality, mapping quality, insert length, and mapping type (normal, mate far and near, and mate flip) were plotted for both DBS and blood samples.

Coverage analysis

Coverage analysis was carried out at both the whole genome and whole exome levels. For whole exome coverage, read depth and percentage of bases with low coverage (threshold of 20X) were calculated on the regions of the SureSelect Human All Exon V7 manifest covering 35.8 Mb and 19,634 genes. Further, the correlation between whole-exome region-wise coverage of DBS and blood samples was calculated. In addition, the correlation between whole-exome region-wise coverage of DBS and blood samples was calculated.

To study the equivalence of the DBS and the blood samples for CNV calling, coverage analysis at the whole genome level was carried out. The genome was divided into windows of size 5kbp. For each blood-DBS sample pair, windows with an average coverage of less than 10 × or more than 250 × in the blood sample were ignored. Chromosomes X and Y were ignored for uniformity of analysis across all sample pairs. The read count was normalized by the total number of reads in the sample, and the ratio of normalized read counts in the DBS sample to that in the blood sample was calculated. Windows with the normalized read count ratio < 0.7 or > 1.3 were considered as discrepant. These thresholds were used by Ganapathy et al. (2019) for reliable detection of copy number alterations using Strand NGS [9].

CNV calling

To detect CNVs, the genome was divided into small windows [10], and read counts were obtained for each of these windows across all samples. Windows with fewer than five and more than 100,000 reads were ignored. For each window, read count ratio was computed for each sample by comparing against all others in the same matrix-specific batch. CNV regions were detected from the ratios by a process called segmentation in which windows are merged into larger segments if they have similar ratios. Two segments were combined only if the distance between them was less than 10% of the total length of the two segments. Segments with amplifications needed to satisfy an additional criterion that the difference in the copy numbers was less than 20% of their mean copy number. The minimum segment size was set to five windows. CNVs were identified in each sample before and after correcting for GC bias (i.e., the effect of GC content on read coverage across a genome).

SNV/InDel calling

SNVs and InDels were detected in the samples using the germline variant calling method in Strand NGS. SNV/InDel concordance between two samples was calculated as

where C is the number of variants common to both samples and U1 and U2 are variants unique to samples 1 and 2 respectively. Concordance was calculated for substitutions and for InDels after excluding regions annotated by RepeatMasker (size: 1448 Mb) from UCSC Genome Browser. Any variant with read depth < 20 or % allele frequency (%AF) < 20% were excluded because they are likely to be false positives. There was < 1% difference (p > 0.05) in the percentage of filtered variants between DBS and blood samples across all the 12 pairs.

Mitochondrial heteroplasmy, haplotypes, and copy number changes

Raw FASTQ files from both DBS and blood were aligned against the mitochondrial reference genome (Cambridge reference sequence NC_012920.1 using Strand NGS ver. 3.3). Only reads that were > 95% identity matched to the reference were used. Realignment was carried out to improve the alignment of reads that were split because of the circular genome. Uniquely mapping reads were used to calculate the average nuclear genome coverage. The effective genome size of 2,827,437,033 bp was used. The mitochondrial copy number was calculated as [11]

The nuclear coverage was calculated as follows:

To estimate heteroplasmic mitochondrial mutations, variant calling at allele frequency (AF) ≥ 2% were performed for SNV identification on the mitochondrial genome (after applying standard filters on read quality, alignment and mapping quality, and strand bias). Heteroplasmic mitochondrial mutations were identified with the following criteria: (a) sequence quality > 20, (b) coverage > 200X, (c) mutant AF between 2 and 90%, and (d) variant present in < 20% of samples. Additionally, for variants between 2 and 5% AF, we ensured that the %AF was at least three standard deviations away from the trimmed mean.

For haplogroup analysis, SNV files were exported from Strand NGS with only mtDNA substitutions and converted to the hsd format using custom scripts. The hsd files were input to the HaploGrep tool (v2) for haplogroup classification [12, 13]. A phylogenetic tree was constructed using default settings. Clustering analysis was performed on all the DBS and blood samples to assess mitochondrial SNV (mtSNV) concordance and to identify contamination.

Telomere length estimation

TelSeq software was used to estimate the length of the telomeres in the DBS and blood samples. Aligned BAM files with all reads were used as inputs. Telomere length was calculated as described in Ding et al. [14]. Briefly, the number of telomere signature TTAGGG repeats, GC content of the reads, and a constant based on the length of the genome were used in the calculations. A threshold of seven was applied for the number of repeats in a read, and a GC content window of 48–52% was used for the length estimate, which were the default settings of the tool.

Results

Comparison of genomic DNA quality

We extracted genomic DNA (gDNA) from paired DBS and blood samples from 12 subjects. Individual DBS samples consisting of 5–6 punches yielded an average of 311 ng (± 123 ng) of gDNA. Yields from corresponding 200 µl of blood were tenfold higher. Nevertheless, all yields were greater than the 100 ng input recommended for whole-genome library preparation (Table 2). The A260/A280 ratio (an indicator of the purity of nucleic acid samples) values were measured and calculated for gDNA from DBS and blood samples, which were found to be in the reference range of 1.7 to 2. The average size of DNA fragments was 21 kb, for both DBS- and blood-derived DNA. The quality of gDNA extracted from DBS was on par with that of blood.

Comparison of sequencing metrics

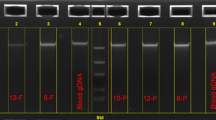

WGS libraries were prepared using all samples and showed similar yield and size (Table 2). All sample libraries were pooled and run on a NovaSeq S4 kit. The samples had an average of 140 GB data and > 0.8 billion reads except for a single blood sample. No significant differences in the sequencing quality control (QC) metrics were evident between DBS and blood samples. QC plots comparing base and read quality distributions, read fractions uniquely mapped to the genome, and read types (such as normal, mate far, mate near, etc.) were very similar for both matrices (Fig. 1a–c, Fig. 1g). Insert lengths were marginally smaller in DBS samples when compared with blood (10–15 bp) (Fig. 1d) but were fairly uniform across all samples within each matrix type.

Comparison of sequencing QC between DBS and blood. Base composition by position in reads in a DBS samples and b blood samples; c read quality distribution in DBS and blood; d insert length distributions in DBS and blood; e distribution of % of low, covered bases (< 20X) across DBS and blood samples; f distribution of average coverage in DBS and blood; and g bar chart of the number of reads based on read alignment status

Comparison of coverage

Coverage analysis was performed at both exome and genome levels. For whole-genome level coverage analysis, the Pearson correlation coefficient computed between the normalized coverage in the DBS and the blood samples was very high for all the pairs (R2 > 0.97). Also, the mean of the normalized coverage ratio between the paired samples, as expected, was close to 1 while the standard deviation was in the range of 0.05–0.08. In addition, windows for which the ratio was < 0.7 or > 1.3 were marked as discrepant. The percentage of such discrepant windows was very low (< 0.035%) for all the pairs, indicating excellent coverage concordance between the two matrices.

In the exome-level analysis, approximately 12% of the reads mapped to exons and were within 1000 bp of the exonic boundaries; the results were similar for DBS and blood samples. Figure 1e, f shows the average coverage and the percentage of under-covered bases with respect to the whole exome for the 12 pairs of samples. Average coverage is in the range of 40 to 55X and the percentage of undercovered bases (i.e., bases with coverage < 20X) is between 1% and 1.5% for both sample types. Correlation coefficients of average coverage per exon between each pair of samples ranged from 0.82 to 0.90. Given that copy number calling is dependent on depth of coverage (DoC) and DoC in DBS is comparable to that of blood samples at the whole-genome and gene levels, copy number calling in DBS samples would be an acceptable surrogate for the same in blood samples. As an example of detecting a clinical-grade CNV, a 1.1Mbp amplification was detected in both DBS and blood samples from one subject (Additional file 1: Figure S1).

SNV/InDel concordance

SNVs and InDels were called in all 12 pairs of samples and analyzed for concordance. Concordance was evaluated for single-base substitutions and InDels separately in each of the 12 pairs before and after masking repeat regions. As a measure of DNA integrity [15], the transition/transversion ratios were calculated for all 12 pairs and were found to be approximately 2 for all cases, the ideal for homologous strands of DNA. This indicated no biased damage in the DBS gDNA. Overall concordance was > 99% for substitutions and > 91% for InDels (Table 3). The number of substitutions and InDels are in the expected ranges of 3–4 million and 200 k–400 k respectively in both matrices [16]. Paired sample t-tests on these metrics did not show any statistically significant difference (p > 0.05) between the two matrices. Thus, DBS provides high-quality data for WGS analysis on par with blood.

Downstream analysis of WGS data

WGS data have also been used in more complex analyses such as (a) haplotyping for ancestry determination, (b) estimating mitochondrial heteroplasmy in a population to understand inheritance of rare mitochondrial disorders, (c) estimating mitochondrial copy numbers, and (d) estimating telomere length as surrogate biomarkers for aging or age-related disorders. For these analyses, assessing whether WGS data from DBS would match the data obtained from blood is critical.

Haplogroup assignment

Both DBS and blood samples paired into individual clades, indicating a high concordance of mtSNVs between the two matrices (Additional file 2: Figure S2). Nine subjects were found to belong to the haplogroup expected for the population of the Indian subcontinent. The remaining three subjects mapped to the H haplogroup (Europe and Central Asia). Findings of H haplogroups (H5a1, H6a1a, and HV6) have been reported among South Indian populations [17,18,19,20].

Heteroplasmy analysis

Table 4 shows that 11 heteroplasmy variants were found across seven subjects (58% of the cohort) with further details in Additional file 3: Table S1. Four subjects had one heteroplasmy, two subjects had two, and one subject had three. Interestingly, six subjects (86%) with observed heteroplasmy were older than 50 years of age (67% of the cohort is > 50). The same variants were observed at similar frequencies in both DBS and blood samples.

Mitochondrial copy number changes

The average mitochondrial copy number (MtCN) from the blood samples was 169 (± 40), which matches the numbers reported in the literature [21] (Table 4). DBS samples had a higher average MtCN of 266 (± 54). A 0.65 coefficient of correlation (positive trend) is seen between the MtCN reported across both matrices. A slight negative trend in MtCN was observed with respect to age in the DBS samples [22].

Telomere length estimation

Telomeres are believed to shorten with every round of cell division and undergo age-dependent attrition. Analyzing their length is an important component of studies that investigate aging and age-related disorders. Ding et al. [14] developed a novel method called TelSeq to measure average telomere length from the whole genome and exome shotgun sequencing data. This approach measures the number of copies of hexameric repeats (TTAGGG or CCCTAA) in the NGS reads. An important observation was that nine of 12 DBS sample estimates were within 10% of the corresponding estimates from blood samples (Fig. 2). Two of the remaining three were close to 15% of blood. Indeed, the median telomere length in DBS was 3.19 (± 0.13) as compared to 3.04 (± 0.28) in blood. However, our sample size was too small to determine any significant relationship between age and telomere length. Our results show that measurements of telomere length from DBS will yield similar results to those from blood.

Discussion

DBS-based sampling and archiving of DNA offer a cost-effective, minimally invasive sample collection method that does not require trained phlebotomists or expensive cold chain shipment [7, 8]. In this study, we explored whether DBS-based collection would facilitate genetic and genomic analysis in epidemiological and population-based studies that involve field collection of specimens. While previous NGS studies have compared DBS DNA libraries with matched blood DNA libraries for targeted regions of the genome [5], comprehensive downstream analysis of whole-genome sequencing is pending. In this study, we compared WGS data from matched DBS and blood samples collected from 12 individuals. The goal was to systematically compare and document all quality parameters and data from both sample matrices for WGS analysis. Our cohort was chosen to include an equal number of male and female subjects with ages ranging from 40 to 85 years to specifically address challenges in downstream analyses relevant to aging studies and age-related disorders.

Our results show close to identical performance in the yield and profiles of the NGS libraries from both DBS and blood. While the DNA yield from two saturated DBS spots (5–6 punches) was one-tenth (~ 300–400 ng) of the quantity of DNA obtained from 200 µl of venous blood, the quantity from both sample types was sufficient for downstream library preparation. The DBS libraries showed no loss of diversity of molecules at this level of DNA yield. Quality parameters such as coverage, base quality, read mapping quality and total number of SNVs were similar in both matrices. These sequencing metrics were within acceptable ranges as known from literature on WGS using blood [5]. DNA from DBS samples may be slightly more nicked than blood because we observed that DBS library inserts were roughly 10–15 bp shorter. However, given that DBS-derived libraries [5, 6] had a similar depth of coverage as that of matched blood, any compromise in molecular diversity affecting downstream analysis can be ruled out. More importantly, all 12 samples had a tight distribution for yield and quality, indicating high reproducibility of data between DBS and blood. SNVs, InDels, and CNVs detected in DBS and blood also showed excellent concordance.

We then evaluated the quality of DBS-derived data for several downstream analyses often used in research pertaining to ancestry, aging, and age-related disorders. These analyses included determining haplogroups and estimating mitochondrial heteroplasmy, mitochondrial copy number changes, and telomere length shortening. Mitochondrial SNV-based haplogroup and heteroplasmy analyses on DBS- and blood-derived DNA gave identical results. As expected, the haplogroup assignments revealed that 75% of the subjects belonged to the M subgroup, which is predominant in the Indian subcontinent. The remaining subjects were part of the H haplogroup, which has also been previously reported in the Indian population.

Mitochondrial heteroplasmy, a parameter analyzed in the context of age-related disorders, was identified mostly in subjects above 50 years of age. We observed that the heteroplasmy variants identified in DBS agreed with those found in blood. In the case of mitochondrial CNV analysis, absolute copy number estimates were higher in DBS data; similar observation is reported by Anderson et al. [23]. However, the trends were similar across matrix-specific samples. While the technical reasons that give rise to the differences in these estimates are unclear, this could be attributed to either the number of platelets captured in the sample preparations [24, 25], the differences in the extraction methods of the two sample types, or the smaller insert size of DBS-derived NGS libraries.

Telomere lengths were comparable between DBS and blood: in nine of the 12 samples, estimates from DBS were within 10% of those from venous blood. Effects of age-related shortening on telomere lengths were not observed in our data. To identify definitive trends, a larger cohort is required with sufficient subjects in each age group. Interestingly, less variance in telomere lengths was observed in the DBS data. Ding et al. [14] show that increased coverage reduces variability in telomere length estimation by TelSeq. DBS data show that coverage is generally higher and more uniform than from blood. The aforementioned analyses may require further analysis from large cohort studies using DBS.

Conclusions

In summary, DBS provides excellent WGS data for genome-wide SNV, InDel, and copy number analyses. Haplotype analysis and heteroplasmy calculations were on par with venous blood samples. Given the ease of sample collection, transport, and storage, DBS is a robust sample type for genomic analysis in large population-based studies.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to subject confidentiality. Sequencing data (not subject identification information) are available upon request from Strand Life Sciences (contact via email to shanmukh@strandls.com or chandru@strandls.com) for researchers who meet the criteria for access to sequencing data.

Abbreviations

- WGS:

-

Whole-genome sequencing

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- DBS:

-

Dried blood spots

- SNV:

-

Single nucleotide variant

- InDels:

-

Insertions and deletions

References

Grüner N, Stambouli O, Ross RS. Dried blood spots—preparing and processing for use in immunoassays and in molecular techniques. J Vis Exp JoVE. 2015;97. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4397000/.

Uzicanin A, Lubega I, Nanuynja M, Mercader S, Rota P, Bellini W, et al. Dried blood spots on filter paper as an alternative specimen for measles diagnostics: detection of measles immunoglobulin m antibody by a commercial enzyme immunoassay. J Infect Dis. 2011;204(suppl_1):S564–9.

Scriver CR. A simple phenylalanine method for detecting phenylketonuria in large populations of newborn infants, by Robert Guthrie and Ada Susi, Pediatrics, 1963;32:318–343. Pediatrics. 1998;102(Supplement 1):236–7.

Cordovado SK, Earley MC, Hendrix M, Driscoll-Dunn R, Glass M, Mueller PW, et al. Assessment of DNA contamination from dried blood spots and determination of DNA yield and function using archival newborn dried blood spots. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;402(1):107–13.

Hollegaard MV, Grauholm J, Nielsen R, Grove J, Mandrup S, Hougaard DM. Archived neonatal dried blood spot samples can be used for accurate whole genome and exome-targeted next-generation sequencing. Mol Genet Metab. 2013;110(1):65–72.

Bassaganyas L, Freedman G, Vaka D, Wan E, Lao R, Chen F, et al. Whole exome and whole genome sequencing with dried blood spot DNA without whole genome amplification. Hum Mutat. 2018;39(1):167–71.

McDade TW, Williams S, Snodgrass JJ. What a drop can do: Dried blood spots as a minimally invasive method for integrating biomarkers into population-based research. Demography. 2007;44(4):899–925.

Martial LC, Aarnoutse RE, Schreuder MF, Henriet SS, Brüggemann RJM, Joore MA. Cost evaluation of dried blood spot home sampling as compared to conventional sampling for therapeutic drug monitoring in children. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(12):e0167433.

Ganapathy A, Mishra A, Soni MR, Kumar P, Sadagopan M, Kanthi AV, et al. Multi-gene testing in neurological disorders showed an improved diagnostic yield: data from over 1000 Indian patients. J Neurol. 2019;266(8):1919–26.

Strand NGS Manual, Version 3.3, Build 238391 [Internet]. Strand Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd.; 2011. https://www.strand-ngs.com/.

Wachsmuth M, Hübner A, Li M, Madea B, Stoneking M. Age-related and heteroplasmy-related variation in human mtDNA copy number. PLOS Genet. 2016;12(3):e1005939.

van Oven M, Kayser M. Updated comprehensive phylogenetic tree of global human mitochondrial DNA variation. Hum Mutat. 2009;30(2):E386–94.

Weissensteiner H, Pacher D, Kloss-Brandstätter A, Forer L, Specht G, Bandelt H-J, et al. HaploGrep 2: mitochondrial haplogroup classification in the era of high-throughput sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44(W1):W58-63.

Ding Z, Mangino M, Aviv A, Consortium U, Spector T, Durbin R. Estimating telomere length from whole genome sequence data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42(9):e75–e75

Wang J, Raskin L, Samuels DC, Shyr Y, Guo Y. Genome measures used for quality control are dependent on gene function and ancestry. Bioinformatics. 2015;31(3):318–23.

GenomeAsia100K Consortium. The GenomeAsia 100K Project enables genetic discoveries across Asia. Nature. 2019;576(7785):106–11.

Marrero P, Abu-Amero KK, Larruga JM, Cabrera VM. Carriers of human mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup M colonized India from southeastern Asia. BMC Evol Biol. 2016;16(1):246.

Maji S, Krithika S, Vasulu TS. Phylogeographic distribution of mitochondrial DNA macrohaplogroup M in India. J Genet. 2009;88(1):127–39.

Harney É, Nayak A, Patterson N, Joglekar P, Mushrif-Tripathy V, Mallick S, et al. Ancient DNA from the skeletons of Roopkund Lake reveals Mediterranean migrants in India. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):3670.

Palanichamy MG, Mitra B, Zhang C-L, Debnath M, Li G-M, Wang H-W, et al. West Eurasian mtDNA lineages in India: an insight into the spread of the Dravidian language and the origins of the caste system. Hum Genet. 2015;134(6):637–47.

Xia C-Y, Liu Y, Yang H-R, Yang H-Y, Liu J-X, Ma Y-N, et al. Reference intervals of mitochondrial DNA copy number in peripheral blood for Chinese minors and adults. Chin Med J (Engl). 2017;130(20):2435–40.

Ding J, Sidore C, Butler TJ, Wing MK, Qian Y, Meirelles O, et al. Assessing mitochondrial DNA variation and copy number in lymphocytes of ~ 2,000 Sardinians using tailored sequencing analysis tools. PLOS Genet. 2015;11(7):e1005306.

Anderson C, Fry RC, Hartwell H, Kleeberger C, Sandler DP, Nichols HB. Measurement of mitochondrial DNA copy number in dried blood spots: a pilot study. Mitochondrion. 2021;56:35–9.

Yang ZW, Yang SH, Chen L, Qu J, Zhu J, Tang Z. Comparison of blood counts in venous, fingertip and arterial blood and their measurement variation. Clin Lab Haematol. 2001;23(3):155–9.

Hurtado-Roca Y, Ledesma M, Gonzalez-Lazaro M, Moreno-Loshuertos R, Fernandez-Silva P, Enriquez JA, et al. Adjusting MtDNA quantification in whole blood for peripheral blood platelet and leukocyte counts. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0163770.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our gratitude to Dr. A. Ravindra and Dr. K. S. James for facilitating the study and the study design, and Alyssa Shiraishi Lubet for her advice on designing the study questionnaire. Additionally, we would like to acknowledge the contributions of Mayuri Vegad in accessioning the samples and Manasa BP for reviewing the WGS literature. We would also like to thank Ashwini Manjunath and Nitish Kumar Pal for their contributions toward the analysis pipeline and Swaraj Basu for his inputs on the mitochondrial data analysis. We gratefully acknowledge and thank the research assistance and support from Dr. P. Prabhuswamy, Mr. Yeshvanth B.K., Ms. Bhavyashree T.N., Mr. Mujamil Pasha, and Mr. R. Srinivas, particularly in the collection of data from the selected households. Finally, we are grateful to the respondents from Kunigal Taluk, Tumakuru District of Karnataka, for consenting to be a part of our study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Institute on Aging, USA (Grant # 5P30AG024409-14). The funder had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PA, AA, VV, VG, RH, VC, DEB conceptualized the project. PA, BPV, LS, TSS, RD, and AA coordinated the sample collection. YKS, LP, AS, VV, VG, VC designed the experiments and bioinformatics workflow. Formal analysis was conducted by PA, SK, AKH, VGR, DA, SCS, YKS, LP, AS, VV, and VGR. PA, SK, AKH, VG, AA, RD, DA, and SCS drafted the manuscript, which was reviewed, revised, and approved by all co-authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research study was approved independently by the ethics/institutional boards of the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health (HSPH IRB protocol # IRB17-1169), the Institute of Social and Economic Change, and Strand Life Sciences. Written informed consent was obtained from the respondents for the interview and the collection and analysis of the DBS and venous blood samples.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors of this manuscript have the following competing interests: VC and RH are Director and CEO of SLS, respectively. PA, SK, AKH, VGR, DA, SCS, YKS, LP, AS, VV, and VG are employees of SLS. There authors declare no other financial or non-financial competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

Copy number alteration in a blood and DBS sample pair. A 1.1Mbp amplification identified in the blood sample of subject, S-10438, was also identified in the matched DBS sample. The figure shows elevated normalized coverage ratios of each region in the 1.1Mbp stretch for the sample of interest when compared to the remaining samples.

Additional file 2:

Assignment of matched blood-DBS samples to mitochondrial haplogroups. Mitochondrial SNVs identified in each sample were used to assign them to haplogroups. The cladogram in the figure shows that each pair of matched blood and DBS are assigned to the individual clades thus demonstrating high concordance between blood and DBS samples.

Additional file 3:

List of heteroplasmy variants identified in subjects. The table lists the mitochondria heteroplasmy variants shortlisted in blood and DBS samples along with the %allele frequencies.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Agrawal, P., Katragadda, S., Hariharan, A.K. et al. Validation of whole genome sequencing from dried blood spots. BMC Med Genomics 14, 110 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-021-00951-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-021-00951-w