Abstract

Background

Abdominal tuberculosis is an uncommon variant of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. It accounts for 3.5% of extrapulmonary tuberculosis. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis is still a challenge due to its non-specific symptoms. Abdominal tuberculosis and ovarian cancer may show similar symptoms, laboratory and imaging features. The goal of our report is to emphasize for the need of a diagnostic approach based on clinical manifestations, laboratory, imaging findings, and additional tests for considering a diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis rather than ovarian cancer.

Case presentation

We report 3 cases of abdominal tuberculosis in our Onco-gynaecology Division, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Sardjito Hospital, Yogyakarta, Indonesia in 2018 which were previously diagnosed as ovarian malignancy and managed surgically. All of our patients experienced abdominal pain and enlargement but only two of them had significant weight loss. The general symptoms were typically found in onco-gynaecology patients, especially in those with ovarian malignancy. Ultrasound examination showed multilocular masses, 2 of them with solid parts and ascites. Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) levels were found increasing in those three patients. All of them were treated surgically and diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis was established through the histopathological result of tissue biopsy. Based on our cases and literature, we consider the need of a diagnostic approach to differentiate abdominal tuberculosis from ovarian malignancy, an attempt to avoid unnecessary invasive procedures that put burden risk for the patients.

Conclusion

Minimally invasive tests to establish the diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis should be optimized to reduce the burden risk of laparotomy. Careful diagnostic steps should be followed to avoid wrong diagnosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis is an infectious disease caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which mostly affects the lung, but can also affect other organs, referred as extra-pulmonary tuberculosis [1]. Abdominal tuberculosis contributes about 3.5% of extra-pulmonary cases. Abdominal focuses of mycobacterium were the result of hematogenous spread from primary pulmonary focuses, or may also be caused by swallowed bacilli which transported through lymphatic by macrophage to the mesenteric lymph nodes [2].

The most common presenting symptoms were abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, abdominal mass, and ranges of another symptoms including vomiting, constipation, abdominal tenderness, and signs of ascites and peritonitis [3]. Abdominal tuberculosis frequently shares common symptoms with ovarian malignancy. Several laboratories and imaging modality are often utilized in attempt to distinguish between those two. In some patient surgery was performed on indication of ovarian tumor due to similarity of physical examination and imaging result. Diagnostic approach is needed to eliminate unnecessary laparotomy due to wrong diagnosis.

Case presentation

Three cases of abdominal tuberculosis previously diagnosed as ovarian malignancy were identified in our Onco-gynecology Division, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dr. Sardjito Hospital during year 2018. All of them were treated surgically and diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis was established through histopathological result of tissue biopsy. The summary of each case is presented below (Table 1).

Case 1

A 16 years old female was referred from district hospital. Her main complaints were abdominal pain and enlargement for the last 2 months. The suspicion of malignant ovarian cyst was established from referring obstetrician based on abdominal ultrasound. Defecation and micturition pattern were normal.

Her menstrual cycle was normal, with 28–30 days’ cycle and 4–5 days of menstrual period in each cycle. There was no history of fever, vaginal discharge, chronic illness, chronic cough, and significant weight loss. There was no obvious contact with person with tuberculosis or those in tuberculosis therapy.

A thorough physical examination revealed slightly distended abdomen, with palpable cystic mass up to 2 cm above pubic symphysis. From bimanual palpation, uterus was palpable within normal size, with palpable cystic mass in left adnexa.

Abdominal ultrasound showed a cystic mass in left adnexa, measured 43 × 37 mm, with solid parts and irregular border, along with peritoneal free fluid. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan further showed a complex left ovarian cyst with ascites, suggesting malignant appearance. CT also founded right renal pelviectasis, hepatosplenomegaly, and bilateral inguinal lymphadenopathy.

Laboratory workup for tumor biomarker was performed, with result supporting the suspicion of malignancy process (CA-125: 886 U/mL).

Exploratory laparotomy was performed to found the fragile, solid mass which filled most of abdominal cavity and adhered to the pelvic wall, a condition commonly known as ‘frozen pelvis’, causing further exploration without making massive tissue destruction was impossible. Operator decision was to close the abdomen after collecting some tissue for histopathology workup.

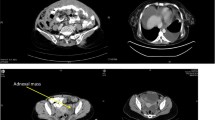

Histopathology report came out a week later, revealing a granulomatous inflammation related to tuberculosis process (Fig. 1). The diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis was subsequently established.

Case 2

A 16 years old female was referred from a private local hospital with suspected ovarian malignancy. She reported painful abdominal enlargement since the last year along with nausea and vomiting and marked weight loss. No history of fever, chronic cough, nor contact with tuberculosis-positive persons. Previous ultrasound examination showed ovarian mass with malignant appearance.

She appeared cachexic, with body mass index only 15.8 kg/m2. Abdominal palpation revealed a lower abdominal mass originating from pelvic cavity up to umbilical level. Abdominal ultrasound showed large multilocular abdominal mass filling the pelvic cavity. No ascites fluid was found. Unfortunately, abdominal CT scan was not performed for this patient. Tumor marker was checked and CA-125 was found high (481 U/ml).

She was diagnosed with suspected ovarian malignancy and laparotomy was planned. During surgery, parietal peritoneum was found thick and easily bleed. After it was opened, massive adhesion of abdominal organ was found and further exploration was considered impossible without damaging surrounding organs. Surgery was completed after collecting peritoneal tissue to be sent to pathology laboratory.

Histopathological result showed granulomatous inflammation specific for tuberculous infection. The patient then was sent to internal department to receive extrapulmonary tuberculosis drug regimen.

Case 3

A 32 years old female was referred from internal department with suspected ovarian malignancy. She felt painful abdominal enlargement since the last 4 months due to massive ascites. Abdominal paracentesis had been done twice to reduce the ascitic fluid and temporarily eliminated the symptoms. Ascites fluid culture showed numerous Gram-positive coccus and Gram-negative bacillus, but acid-fast staining was not performed. Lower abdominal ultrasound ordered by internal department revealed abdominal cystic mass from ovarian origin.

The patient experienced significant weight loss for the last 4 months with body mass index 14.7 kg/m2. A large abdominal cystic mass was palpable through physical examination and confirmed by abdominal ultrasound examination. The mass was multiloculated, with solid parts and highly vascularized. Significant amount of ascites was seen.

Abdominal CT scan showed small multilocular cyst from left and right adnexa along with marked ascites. There is no paraaortic, mesenteric, and iliac lymph nodes enlargement. Abdominal paracentesis was done, and culture workup showed marked negative Gram-staining bacilli. Acid-fast stain was not performed. Tumor marker for epithelial ovarian malignancy was rising (CA-125: 203).

The patient was suspected to have ovarian malignancy and planned to have laparotomy procedure. During procedure, peritoneal cavity was filled with yellowish caseous necrotic tissue pathognomonic for tuberculous process, forming a cystic-like mass. Four liters of the tissue was evacuated and was sent for culture and cytology workup. Peritoneal biopsy was done, and no further exploration was performed because of massive adhesion. The result came out a week later, all confirmed tuberculous infection.

Discussion

The most common presenting symptoms of abdominal tuberculosis are abdominal pain (95%), followed by weight loss (88%), fever (84.6%), abdominal mass (46.1%) and ranges of another symptoms including vomiting, constipation, abdominal tenderness, and signs of ascites and peritonitis [3]. Meanwhile, increased abdominal size or bloating, urinary urgency, difficulty eating and abdominal/pelvic pain are often reported by patients with ovarian malignancy [4].

All our patients experienced abdominal pain and enlargement but only two of them had significant weight loss. The general symptoms were typically found in onco-gynecologic patients, especially in those with ovarian malignancy. All of them were referred to our department because of suspected ovarian-origin mass showing malignancy signs. Theoretically, abdominal tuberculosis frequently shares common symptoms with ovarian malignancy. Several laboratories and imaging modality are often utilized in attempt to distinguish between those two.

Tumor marker CA-125 was not useful to distinguish abdominal tuberculosis from ovarian malignancy. Numerous case reports and case series showed significantly elevated CA-125 in patient diagnosed with abdominal tuberculosis [5,6,7,8]. Similarly, increased level of CA-125 was found in all our patient. Meanwhile, decrease of serum CA-125 in patient with abdominal tuberculosis receiving course of anti-tuberculosis drug indicating some value of this biomarker in evaluation of tuberculosis treatment [9].

Human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) belong to four-disulfide family of protein and normally act as proteinase inhibitor. Highest expression on HE4 was observed in ovarian malignancy, especially serous and endometrioid adenocarcinoma [10, 11]. The risk of ovarian malignancy algorithm (ROMA) utilizing both CA-125 and HE4 level is comparable to risk of malignancy index (RMI) as diagnostic tool to differentiate ovarian malignancy [12, 13]. HE4 was also found to rise in pulmonal tuberculosis, but its role in detecting abdominal tuberculosis is less understood. A retrospective study found that serum HE4 in peritoneal tuberculosis was significantly lower than that in ovarian malignancy. An optimal cut-off value, 151.4 pmol/l, was established to differentiate between those two [14].

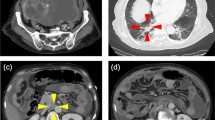

In our cases, 3 patients came with ultrasound examination showing multilocular mass, 2 of them with solid parts and ascites. These 2 patients were considered to require further imaging workup, so abdominal multiple CT scan with contrast was ordered (Fig. 2).

The first patient had complex left ovarian cyst with loculated ascites, thus suspected as ovarian malignancy. In this patient, bilateral inguinal lymph nodes enlargement and marked peritoneal thickening was found.

The third patient was suspected with ovarian malignancy due to appearance of multiloculated cystic mass originated from ovary that infiltrate uterine tissue along with ascites and smooth peritoneal thickening. There was no lymph nodes enlargement.

Abdominal scan was commonly used imaging in patient with suspected ovarian mass. In a study describing CT scan result of 10 patients with confirmed abdominal tuberculosis, omental and mesenteric thickening along with ascites were found in all patients, while cystic ovarian mass or enlargement and peritoneal implants were not consistently seen [15]. The parietal peritoneum involvement in CT seemed to have diagnostic value, in which most of patients with abdominal tuberculosis will have smooth thickening of parietal peritoneum while irregular and nodular involvement was commonly found in peritoneal carcinomatosis [16]. Although ultrasound and CT scan have been considered to be reliable in diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis [17], in many cases it failed to distinguish abdominal tuberculosis from ovarian malignancy [5, 18].

Several tests were available to detect mycobacterium from ascites. Unfortunately, none of them was performed to our patient because abdominal tuberculosis was not suspected at the first place.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) of ascetic fluid for mycobacterium can be considered for diagnosis and should at least be attempted before surgical intervention, but this technique is not widely available [5]. Furthermore, reports suggest that the although performance of the various PCR tests is reasonably good with sensitivity reaching up to 95% in smear-positive patients, the same success has not been duplicated in smear-negative patients and the sensitivity attained has been disappointingly low (48%) [19].

The X-pert MTB/RIF assay is a nucleic acid amplification test that is reliable to diagnose tuberculosis diseases and drug resistance rapidly. Its use now is recommended as the preferred initial test to establish the diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis [20]. However, utilization of this method for ascites fluid analysis to diagnose abdominal tuberculosis is still questioned due its poor sensitivity [21, 22].

Adenosine deaminase (ADA), purine degrading enzyme, is widely distributed in tissue and body fluid. ADA is necessary for T lymphocytes proliferation and differentiation, a prominent process in immune cellular response against M. tuberculosis. A meta-analysis found that ADA level of ascites fluid above 39 IU/L was reliable to diagnose peritoneal tuberculosis with 100% sensitivity and 97.2% specificity [23]. This finding was supported by numerous study [16, 18, 24].

T-cell-based interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) was considered as a substitute for tuberculin skin test with higher sensitivity and specificity to detect mycobacterium infection [25]. Nevertheless, suboptimal result is possible due to its inability to distinguish latent infection from active diseases. A meta-analysis involving 1711 patients with blood samples to determine the accuracy of IGRA in diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis showed sensitivity between 72 and 90%, while the specificity ranged between 68 and 82% (depending on various IGRA test commercially available) [26]. While the sensitivity and specificity of IGRA is lower than ADA test, it gives diagnostic advantages because invasive procedure to obtain the ascites fluid is not necessary.

Laparoscopy is an important tool in the management of such cases to avoid extended surgery. While visual diagnosis using this minimally invasive technique was highly accurate, mycobacteria was only scarcely found on histological sections [27]. This is due to paucibacillary nature of tuberculous peritonitis, making the classical method of Ziehl-Neelsen stain and mycobacterium culture from ascetic fluid or peritoneal biopsy such a poor diagnostic tools [28].

Utilizing Xpert MTB/RIF from tissue samples could be another alternative. The pooled estimate of sensitivity was calculated as 81.2% (95% CI, 67.7–89.9%) while the pooled specificity was 98.1% (95% CI, 87.0–99.8%) compared to tissue culture [29].

Based on our cases and above-mentioned studies and literatures, we consider the need of a diagnostic approach to differentiate abdominal tuberculosis from ovarian malignancy as we propose below (Table 2). Patient with history, physical examination, ultrasound, and abdominal CT scan suggestive of abdominal tuberculosis deserve further evaluation to differentiate between those two conditions in order to avoid unnecessary invasive procedure.

From the recent study, adenosine deaminase assay of ascites fluid gives the best accuracy in diagnosing abdominal tuberculosis due its high sensitivity and specificity. IGRA test using blood sample can be the alternatives in such case where invasive procedure cannot be performed. We propose to do ADA test and IGRA test in case ultrasound or CT scan findings were suggestive for abdominal TB. If ADA test with or without IGRA test is positive then we may consider managing the patients as abdominal tuberculosis.

Laparoscopy is preferred procedure over exploratory laparotomy, not only does it allow the inspection of the peritoneum but also offers the option of obtaining specimens for histology, while giving lower risk of surgical morbidity. Despite of attempts to make it minimally invasive, more than half of patients need laparotomy to established diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis [40].

Conclusions

In addition to ovarian cancer, the diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis should always be considered in patients with abdominal distension, pain, weight loss, and signs and symptoms of ascites, especially in an endemic area of tuberculosis. Careful diagnostic steps should be followed to avoid the wrong diagnosis. Minimally invasive procedures should be optimized to reduce the burden risk of laparotomy. Exploratory laparotomy could be performed to establish a diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis to rule out ovarian malignancy when the standard tests were negative.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- ADA:

-

Amine deaminase

- CA 125:

-

Cancer antigen 125

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- HE4:

-

Human epididymis protein 4

- IGRA:

-

Interferon gamma release assay

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. p. 1–262.

Rathi P, Gambhire P. Abdominal Tuberculosis. J Assoc Physicians India. 2016;64(2):38–47.

Hossain SM, Rahman MM, Hossain SA, Ahmed SFU. Mode of presentation of abdominal tuberculosis. Bangladesh Med J Khulna. 2013;45(1–2):5–7.

Goff BA, Mandel LS, Drescher CW, Urban N, Gough S, Schurman KM, et al. Development of an ovarian cancer symptom index: possibilities for earlier detection. Cancer. 2007;109(2):221–7.

Patel SM, Lahamge KK, Desai AD, Dave KS. Ovarian carcinoma or abdominal tuberculosis?-a diagnostic dilemma: study of fifteen cases. J Obstet Gynecol India. 2012;62(2):176–8.

Thakur V, Mukherjee U, Kumar K. Elevated serum cancer antigen 125 levels in advanced abdominal tuberculosis. Med Oncol. 2001;18(4):289–91.

Boss JD, Shah CT, Oluwole O, Sheagren JN. TB peritonitis mistaken for ovarian carcinomatosis based on an elevated CA-125. Case Rep Med. 2012;2012:215293.

Chien JC-W, Fang C-L, Chan WP. Peritoneal tuberculosis with elevated CA-125 mimicking ovarian cancer with carcinomatosis peritonei: crucial CT findings. EXCLI J. 2016;15:711–5.

Yilmaz A, Ece F, Bayramgürler B, Akkaya E, Baran R. The value of Ca 125 in the evaluation of tuberculosis activity. Respir Med. 2001;95(8):666–9.

Simmons AR, Baggerly K, Bast RC. The emerging role of HE4 in the evaluation of advanced epithelial ovarian and endometrial carcinomas Archana. NIH Public Access. 2014;27(6):548–56.

Galgano MT, Hampton GM, Frierson HF Jr. Comprehensive analysis of HE4 expression in normal and malignant human tissues. Mod Pathol. 2006;19(6):847–53.

Aarenstrup M, Sandhu N, Høgdall C, Jarle I, Nedergaard L, Lundvall L, et al. Evaluation of HE4 , CA125 , risk of ovarian malignancy algorithm ( ROMA ) and risk of malignancy index ( RMI ) as diagnostic tools of epithelial ovarian cancer in patients with a pelvic mass ☆. Gynecol Oncol. 2012;127(2):379–83.

Moore RG, Jabre-raughley M, Brown AK, Robison KM, Miller MC, Allard WJ, et al. Comparison of a novel multiple marker assay vs the Risk of Malignancy Index for the prediction of epithelial ovarian cancer in patients with a pelvic mass. YMOB. 2010;203(3):228.e1–6.

Zhang L, Chen Y, Liu W, Wang K. Evaluating the clinical significances of serum HE4 with CA125 in peritoneal tuberculosis and epithelial ovarian cancer peritoneal tuberculosis and epithelial ovarian cancer. Biomarkers. 2016;5804(2):168.

Bilgin T, Karabay A, Dolar E, Develioǧlu OH. Peritoneal tuberculosis with pelvic abdominal mass, ascites and elevated CA 125 mimicking advanced ovarian carcinoma: a series of 10 cases. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2001;11(4):290–4.

Kang SJ, Kim JW, Baek JH, Kim SH, Kim BG, Lee KL, et al. Role of ascites adenosine deaminase in differentiating between tuberculous peritonitis and peritoneal carcinomatosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(22):2837–43.

Sinan T, Sheikh M, Ramadan S, Sahwney S, Behbehani A. CT features in abdominal tuberculosis: 20 years experience. BMC Med Imaging. 2002;2(April 1982):1–7.

Uzunkoy A, Harma M, Harma M. Diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis: experience from 11 cases and review of the literature. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(24):3647–9.

Sanai FM, Bzeizi KI. Systematic review: tuberculous peritonitis – presenting features , diagnostic strategies and treatment. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:685–700.

World Health Organization. TB CARE I. International Standards for Tuberculosis Care; 2014. p. 1–92.

Kumar S, Bopanna S, Kedia S, Mouli P, Dhingra R, Padhan R, et al. Evaluation of Xpert MTB/RIF assay performance in the diagnosis of abdominal tuberculosis. Intest Res. 2017;15(2):187–94.

Ahmad R, Changeez M, Khan JS, Qureshi U, Tariq M, Malik S, et al. Diagnostic Accuracy of Peritoneal Fluid GeneXpert in the Diagnosis of Intestinal Tuberculosis, Keeping Histopathology as the Gold Standard. Cureus. 2018;10(10):e3451.

Riquelme A, Calvo M, Salech F, Valderrama S, Pattillo A, Arellano M, et al. Value of adenosine deaminase (ADA) in ascitic fluid for the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis: A meta-analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;40:705–10.

Ali N, Nath NC, Parvin R, Rahman A, Bhuiyan TM, Rahman M, et al. Role of ascitic fluid adenosine deaminase (ADA) and serum CA-125 in the diagnosis of tuberculous peritonitis. Bangladesh Med Res Counc Bull. 2014;40(3):89–91.

Pai M, Zwerling A, Menzies D. Systematic Review : T-Cell – based Assays for the Diagnosis of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: An Update. Ann Intern Med. 2010;149(3):177–84.

Fan L, Chen Z, Hao X, Hu Z, Xiao H. Interferon-gamma release assays for the diagnosis of extrapulmonary tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Immunoogy Med Microbiol. 2012;65:456–66.

Bhargava DK. Shriniwas, Chopra P, Nijhawan S, Dasarathy S, Kushwaha AKS. Peritoneal tuberculosis: laparoscopic patterns and its diagnostic accuracy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(1):109–12.

Chander A. Diagnostic significance of ascites adenosine deaminase levels in suspected tuberculous peritonitis in adults. J Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;03(03):104–8.

World Health Organization, “Xpert MTB/RIF assay for the diagnosis of Pulmonary and Extrapulmonary TB in adults and children,” Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. p. 1–76.

Das S, Bairagya T, Mandal A. Presenting experience of managing abdominal tuberculosis at a tertiary care hospital in India. J Global Infect Dis. 2011;3(4):344.

Hoffman BL, Schorge JO, Schaffer JI, Halvorson LM, Bradshaw KD, Cunningham FG. William Gynecology. 2nd ed; 2012. p. 400–581.

Malik A, Saxena NC. Ultrasound in abdominal tuberculosis. Abdom Imaging. 2003;28(4):574–9.

Garg S, Kaur A, Kaur Mohi J, Sibia P, Kaur N. Evaluation of IOTA simple ultrasound rules to distinguish benign and malignant ovarian tumours. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(8):TC06–9.

da Rocha EL, Pedrassa BC, Bormann RL, Kierszenbaum ML, Torres LR, D’Ippolito G. Abdominal tuberculosis: a radiological review with emphasis on computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Radiol Bras. 2015;48(3):181–91.

Sahdev A. CT in ovarian cancer staging: how to review and report with emphasis on abdominal and pelvic disease for surgical planning. Cancer Imaging. 2016;16(1):1–9.

Mandavdhare HS, Singh H, Sharma V. Editor's pick recent advance in the diagnosis and management of abdominal tuberculosis. EMJ Gastroenterol. 2017;6(1):52–60

Musto A, Rampin L, Nanni C, Marzola MC, Fanti S, Rubello D. Present and future of PET and PET/CT in gynaecologic malignancies. Eur J Radiol. 2011;78(1):12–20.

Diaz JP, Abu-Rustum NR, Sonoda Y, Downey RJ, Park BJ, Flores RM, et al. Video-assisted thoracic surgery (VATS) evaluation of pleural effusions in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian carcinoma can influence the primary management choice for these patients. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;116(3):483–8.

Mehdi G, Maheshwari V, Afzal S, Ansari HA, Ansari M. Image-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology of ovarian tumors: an assessment of diagnostic efficacy. J Cytol. 2010;27(3):91–5.

Underwood MJ, Thompson MM, Sayers RD, Hall AW. Presentation of abdominal tuberculosis to general surgeons. Br J Surg. 1992;79(10):1077–9.

Acknowledgements

We thank the patients and their parents who have contributed in this study. We are also thank Dr. Ardhanu for technical supporting during the process of this study.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Proceedings Volume 13 Supplement 11, 2019: Selected articles from the 3rd International Symposium on Congenital Anomaly and Developmental Biology 2019 (ISCADB 2019). The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcproc.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-13-supplement-11

Funding

This publication has been funded by the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MNF and APH contributed in design, data collection, analysis, and writing of this manuscript. MNF and APH conceived the study. APH drafted the manuscript, and MNF critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content. APH, collected samples, MNF and APH analyzed data. MNF and APH facilitated all project-related tasks. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Public Health and Nursing, Universitas Gadjah Mada/Dr. Sardjito Hospital ruled the study exempt from approval because this study was a case series. Informed consent has been signed by all patients and/or their parents before joining the study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Fahmi, M.N., Harti, A.P. A diagnostic approach for differentiating abdominal tuberculosis from ovarian malignancy: a case series and literature review. BMC Proc 13 (Suppl 11), 13 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-019-0180-y

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12919-019-0180-y