Abstract

Background

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL)-producing strains of Klebsiella pneumoniae remain a worldwide, critical clinical concern. However, limited information was available concerning ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in giant pandas. The objective of this study was to characterize ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from captive giant pandas. A total of 211 Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates were collected from 108 giant pandas housed at the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding (CRBGP), China. Samples were screened for the ESBL-producing phenotype via the double-disk synergy test.

Result

A total of three (1.42%, n = 3/211) ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains were identified, and characterization of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates were studied by the detection of ESBL genes and mobile genetic elements (MGEs), evaluation of antimicrobial susceptibility and detection of associated resistance genes. Clonal analysis was performed by multi-locus sequencing type (MLST). Among the three ESBL-producing isolates, different ESBL-encoding genes, including blaCTX-M, and blaTEM, were detected. These three isolates were found to carry MGEs genes (i.e., IS903 and tnpU) and antimicrobial resistance genes (i.e., aac(6')-Ib, aac(6')-I, qnrA, and qnrB). Furthermore, it was found that the three isolates were not hypermucoviscosity, resistant to at least 13 antibiotics and belonged to different ST types (ST37, ST290, and ST2640).

Conclusion

Effective surveillance and strict infection control strategies should be implemented to prevent outbreaks of ESBL-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in giant pandas.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae) is an important human pathogen causing numerous infections in hospitals, long-term care facilities, and are associated with community-acquired infection. The bacteria infect the lungs, urinary tract, and surgical sites, causing soft tissue infections and bacteremia [1]. The giant panda, Ailuropoda melanoleuca, is one of the world’s most recognized conservation dependent species and is only distributed in the mountainous areas of Sichuan, Gansu, and Shaanxi provinces [2]. The results of the fourth census of wild giant pandas showed that the population has reached 1864 [3], and the current population of captive giant pandas reached 600. With the growth of the captive population of giant pandas and the in-depth study of their diseases, infections with K. pneumoniae have emerged. Wang et. al (1998) reported that giant pandas infected with K. pneumoniae developed hemorrhagic enteritis [4]. Later, a sub-adult giant panda was diagnosed with K. pneumoniae and Escherichia coli infection and subsequently died from hemorrhagic sepsis, with the isolated K. pneumoniae found to be pathogenic to mice [5]. Subsequent cases of genital hematuria, enteritis, and sepsis caused by K. pneumoniae infection in giant pandas were reported [6]. We conducted an etiological study on a dead giant panda found in a nature reserve in Sichuan and discovered the giant panda died of multiple organ dysfunction syndrome caused by K. pneumoniae and Proteus mirabilis infection [7]. This showed that K. pneumoniae infection was a serious threat to the life and health of giant pandas. In addition, studies had shown that K. pneumoniae can be transmitted through the air [8]; therefore, captive animals infected with K. pneumoniae may be a source of zoonotic infection for husbandry staff and even visitors to wildlife centers.

The emergence of antibiotic resistance is an increasingly alarming public health threat due to the fact they undermine the efficacy of antibiotic treatment [9]. Furthermore, it is expected that antibiotic resistance will be the leading cause of global mortality by 2050, possibly exceeding that of cancer [10]. β-lactam antibiotics are among the most frequently prescribed antimicrobials. However, extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBL) have emerged in numerous hospitals worldwide. These enzymes confered resistance to extended-spectrum cephalosporins and related oxyimino-β-lactams (ceftazidime, cefotaxime, and aztreonam) but were predominantly sensitive to carbapenems, cephamycins, and β-lactamase inhibitors such as clavulanic acid [11]. Antibiotics containing β-lactams are commonly used in disease prevention and control in captive pandas. Antibiotics used in giant pandas indicated that β-lactam antibiotics account for about 50% of total usage, while carbapenem antibiotics including imipenem also were used in Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding (CRBGP), China. In the field of human and livestock medicine, researchers have conducted in-depth studies on the clinical isolation of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae regarding drug resistance, genetic toxicity, and molecular epidemiology, and these results have played a positive role in the scientific and effective prevention and control of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae [12,13,14,15]. However, molecular epidemiology studies of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in giant pandas are currently lacking. Therefore, this study aimed to isolate ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae from captive giant pandas, explore the prevalence and genotype of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae, provide a scientific basis for the clinical use of antibiotics, and provide systematic experimental data and a reference basis for preventing and controlling the spread of such bacteria.

Results

Prevalence of ESBL-producing isolates and ESBL-encoding genes

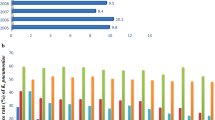

Three ESBL-producing isolates were detected with a prevalence of 1.42% (n = 3/211) in the 108 giant pandas listed. Five ESBL-encoding genes were identified including blaTEM (n = 2), and blaCTX-M (n = 3). Two isolates were detected co-carrying blaTEM, blaCTX-M, and one carrying blaCTX-M (Fig. 1).

The identified antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of K. pneumoniae isolates and ESBL genotype. X1, X2, and RJ are ESBL- positive K. pneumoniae isolates. YL, GZ, KL, YY, CG, XPP, and LL are non- ESBL positive K. pneumoniae isolates as controls. PIP, Piperacillin; MOX, Moxalactam; CAZ, Ceftazidime; CFM, Cefixime; FEP, Cefepime; CTX, Cefotaxime; CL, Cephalexin; CZ, Caphazolin; CRO, Ceftriaxone; FOX, Cefoxitin; TZP, Piperacillin/Tazobactam; CXM, Cefuroxime; CEC, Cefaclor; SAM, Ampicillin/Sulbactam; CFP, Cefoperazone; ZOX, Ceftizoxime; ATM, Aztreonam; MEM, Meropenem; IPM, Imipenem; K, Kanamycin; S, Streptomycin; OFX, Ofloxacin; NOR, Norfloxacin; CIP, Ciprofloxacin; GTX, Gatifloxacin; C, Chloramphenicol; AZM, Azithromycin; TE, Doxycycline; MH, Minocycline; SXT, Compound Sulfamethoxazole; TMP, trimethoprim. "None" indicates a negative detection,“-” indicates no test. R, resistance; I, intermediary sensitive; S, sensitive

String test

The string test results showed that the mucoid string of three ESBL-producing K. pneumonia strains was all lower than 5 mm, indicating that the string test of the three strains were all negative, and further defined that the three strains were not hypermucoviscous.

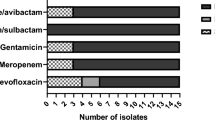

Antimicrobial resistance profiles

The three ESBL-producing isolates were all (n = 3, 100%) resistant to piperacillin, cefotaxime, cephalexin, caphazolin, ceftriaxone, cefuroxime, cefaclor, cefoperazone, kanamycin, streptomycin, doxycycline, and compound sulfamethoxazole (Fig. 1). Isolate X1 was resistant to 16 antibiotics. Isolate X2 was resistant to 13 antibiotics, while isolate RJ was resistant to 25 antibiotics; however, seven non-ESBL-producing isolates were still high resistant to imipenem (57.14%).

Molecular characteristics of ESBL-producing isolates

ESBL-producing isolates X2 and X1 were detected co-carrying two ESBL encoding genes (blaCTX-M and blaTEM), while RJ carried one ESBL-encoding genes (blaCTX-M). Among the three ESBL isolates, three STs, ST2640, ST290, and ST37, were identified (Fig. 2).

Genetic features of 10 K. pneumoniae isolated from giant pandas recovered in 2018 and 2019 with the respective ESBL genes, MGEs gene, and antimicrobial resistance genes. X1, X2, and RJ are ESBL- positive K. pneumoniae isolates. YL, GZ, KL, YY, CG, XPP, and LL are non- ESBL positive K. pneumoniae isolates as controls

Distribution of MGEs genes and antimicrobial resistance genes

All three ESBL-producing isolates and seven non-ESBL-producing isolates tested were carrying at least one of the seven investigated MGEs genes and one of thirteen antimicrobial resistance genes. Three ESBL-producing isolates were carrying 4–5 antimicrobial resistance genes and about 6–7 MGEs genes. Seven non-ESBL-producing isolates were carrying about 1–3 antimicrobial resistance genes and 1–4 MGEs genes. All isolates were carrying aac(6')-Ib and tnpU. Compared with the seven non-ESBL-producing isolates, the three ESBL-producing isolates carried aadA5, rmtB, IS903, and intI1 (Fig. 2). The PCR results showed that ISEcpUP-F- CTX-M-RCJ was positive detected, which means the blaCTX-M was carried by class 1 integron (Fig. 1).

MLST characteristics of ESBL-producing isolates

The MLST is a nucleotide sequence-based method that is adequate for characterizing the genetic relationships among bacterial isolates. The result showed that the distribution of ST type of K. pneumoniae from giant panda was dispersed and presented diversity. The 3 ESBL-positive K. pneumoniae were on different branches, which indicated they had a distant relationship, and at least two allele variants in the ST type existed in the common ESBLs-producing K. pneumoniae (Fig. 3).

The minimum spanning tree of K. pneumoniae isolated from giant pandas. The MLST analysis were based on the ST types of 3 ESBL-positive K. pneumoniae (X1, X2, RJ), 7 non-ESBL-positive K. pneumoniae (YL, GZ, KL, YY, CG, XPP), isolated from giant pandas and 51 other common ESBL-production K. pneumoniae ST types using BioNumerics version 7.6 software. Colour coding corresponds to 10 K. pneumoniae isolated from giant pandas. The number on branches correspond the different loci batwing between different ST-types

Discussion

ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae have been frequently encountered worldwide, especially in hospitals. However, ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae are rarely found in wild animals such as the giant panda [16,17,18]. Therefore, this study intended to analyze the prevalence, genotype, and antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae collected from captive giant pandas. The result showed that the prevalence of ESBL-producing strains among K. pneumoniae isolates from captive giant pandas at the CRBGP was 1.42% (n = 3/211). The prevalence of this ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in giant pandas was lower than in livestock animals and livestock animal products. In the north-west province of South Africa, the most common ESBL-producing bacteria from cattle farms and raw beef was E. coli (58.2%), followed by K. pneumoniae (41.8%) [18]. ESBL-s producing K. pneumoniae collected from adult cattle was 23.4% in North Lebanon [19]. These ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were reported as 53% from diseased dogs in a Veterinary Teaching Hospital in Beijing, China [17], 8.75% were found from raw bulk tank milk of dairy farms in Indonesia [16], 10.9% were detected in cow milk in eastern and north-western India [20] and 17.5% were from companion animals in Europe [21]. The prevalence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in giant pandas was lower than in humans also. The most common ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae detected in a children’s hospital in Japan was E. coli (79.8%), followed by K. pneumoniae (9.1%) [22]. In Iran, the prevalence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae was 43.5% (95% CI 39.3–47.9%) among clinical K. pneumoniae isolates [23]. In Spain, the prevalence of these bacteria in 2017 was 7.2% [24]. In a similar study conducted in Canada from 2010–2012, Karlowsky et al. [25] reported that the prevalence of ESBL-producers was 3.6% among K. pneumoniae isolates [25]. Studies in Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, and Tunisia between 2009 and 2018 revealed a prevalence of these pathogenic bacteria between 38 and 55% in different community settings and hospitals [23]. The prevalence of this pathogenic bacteria was 59.2% among clinical K. pneumoniae isolates in Iran [26]. A possible explanation for the lower prevalence of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in giant pandas is the less frequent use of antibiotics in giant pandas than in humans and domestic animals.

In this study, three ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were detected co-carrying 1 ~ 2 ESBL-encoding genes, including blaTEM and blaCTX-M. Zhou et al. also reported that ESBL-producing E. coli carrying CTX-M gene were detected in captive giant panda in Shanghai, China. Therefore, blaCTX-M may be the main prevalent ESBL-encoding genes in captive giant pandas [27]. Our result was similar to that described in previous studies, where TEM- and CTX-M- types were the main families of ESBL [11, 28]. Furthermore, reports have indicated that CTX-Ms have been rapidly disseminated among populations of gram-negative bacteria in clinical settings in recent years [29, 30]. The blaCTX-M was always connected with mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as integrons, transposons, plasmid and it caused the horizontal gene spread between the same or different species of bacteria [31].

While partial MGEs were detected in this study, including eight different types of MGEs genes, non-ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains carried significantly fewer MGEs genes (n = 2 ~ 3), and the results indicated that the blaCTX-M was carried by the class 1 integron. Based on the fact that ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae was rarely found in captive giant pandas, we suspected that these resistance genes were transmitted by MGEs, and may have been transmitted from humans or other local animals to the captive giant pandas.

The three ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates showed high resistance to many antimicrobial agents (more than 13 antibiotics). In our study, Meropenem was effective against the three ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates, and IPM was effective against about 10% of the strains (n = 10). The three ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae isolates were carrying 5 antimicrobial resistance genes, aac(6')-Ib, tnpU, aac(6')-I, qnrA, and qnrB, which are associated with aminoglycoside and quinolones resistance. In China, ESBL-positive K. pneumoniae strains were > 70% susceptible only to IPM, ertapenem, or amikacin [32]. Similar studies have reported that although the majority of ESBL-producing strains could tolerate high concentrations of most cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones, none exhibited resistance to carbapenems (i.e., imipenem and meropenem) [33]. Interestingly, some of these non-ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae strains were detected carrying aminoglycoside and quinolones-encoding genes that are associated with aminoglycoside and quinolones resistance, however, none of them exhibited resistance to those antimicrobial agents. The reason may be partly due to the expression levels of aminoglycoside and quinolones-encoding genes being quite low in most cases [34].

Previous studies have reported that about 50% of the antibiotic prescriptions for the treatment of K. pneumonia infection were inappropriate and may cause the emergence of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) [35]. We recommend that veterinary professionals paied close attention to the choice of antimicrobial agents to prevent widespread AMR emergence in captive giant pandas.

ST37 was simultaneously shown to be closely associated with ESBLs [36]. And it was thought to be shared between humans and animals [37]. MLST revealed that the three ESBL-positive isolates from giant pandas were ST37, ST290, and ST2640, which means they have a distant relationship. However, ST37 ESBL-positive isolates in pandas were consistent with the main epidemic ST types in China. ST290 was reported to be related with infection of humans and cattle in China, the United States, and Australia [14]. Furthermore, hypervirulent strains of ST290 were detected in healthy captive red kangaroo in Zhengzhou Zoo, China, and also healthy pigs and humans in Thailand [14, 38]. ST2640 K. pneumoniae was detected in bloodstream infection of human in Taiwan [39]. Although ST290 and ST2640 is not a common type of bacteria in China, it was still found in giant pandas.

In conclusion, this was the first ever attempt to study the occurrence and characterization of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae in giant pandas. The result showed that the ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae had existed in giant pandas. But the route of bacterial transmission was not clear. It could be that the use of antibiotics caused genetic mutations in the bacteria, or the horizontal transmission between bacterial, or the transmission by humans or animals in giant panda habitats. Some new techniques that prevented bacterial antibiotic resistance were reported. Mode-of-action-guided chemical modifications of compounds and the development of new antibiotics was considered desirable in dealing with bacterial antibiotic resistance [40]. The successful use of pneumococcal vaccine has brought hope to the use of vaccine against bacterial diseases [41]. Chinese medicine has also been actively applied to bacterial infection [42]. These successful studies may be desirable measures for the prevention and treatment of bacterial diseases in giant pandas in the future, but more research is needed.

Based on the high-frequency resistant to antibiotic of this pathogen, we recommend that the enhancing monitor of bacterial resistance of giant pandas should be performed in clinical veterinarians to facilitate the rational use of antibiotics. And the environmental disinfection of giant panda habitat is also necessary. That may prevent the widespread of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae emergence in the giant pandas.

Limitations of the study

We studied antimicrobial resistance genes and antimicrobial resistance phenotypes of ESBL-producing K. pneumoniae, but it is not clear how these antimicrobial resistance genes regulated the drug resistance phenotypes, and the transmission mechanism of these antimicrobial resistance genes. In a future study, we will further investigate whether antimicrobial resistance genes locate in plasmids and their horizontal transmission mechanisms.

Methods

Subjects

Bacterial isolates and screening for ESBL phenotype

Two hundred and eleven nonduplicated K. pneumoniae isolates were collected from 376 fresh feces of 108 captive giant pandas (female: n = 54, male: n = 54, age: 5–22 years) housed at CRBGP in Sichuan, China during 2018 to 2019. These isolates were identified as K. pneumoniae by Gram staining, 16 s rDNA, and bacterial biochemical identification. All of the isolates were tested for ESBL production by the CLSI-recommended confirmatory double-disc combination test (CLSI, 2019). All of the isolates were screened for ESBL production using cefotaxime (CTX) and ceftazidime (CAZ) alone and in combination with clavulanic acid according to the double-disk synergy test method (DDST) (CLSI, 2019). Phenotypic presence of ESBL in the isolates was determined by detecting diameter enhancement of the inhibition zone of the clavulanate disk and corresponding β-lactam antimicrobial disk. If the enhancement value was > 5 mm, the isolate was presumed to be an ESBL producer [38].

String test

Isolates were cultured on blood agar plates incubated overnight at 37 °C. An inoculating loop was used to touch the colonies gently and lift. Hypermucoviscosity (HV) was defined as a mucoid string > 5 mm in length observed visually (positive string test).

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests of the three ESBL-producing isolates and seven non-ESBL-producing isolates were evaluated using the disk diffusion method to Piperacillin 100 μg (PIP), Moxalactam 30 μg (MOX), Ceftazidime 30 μg (CAZ), Cefixime 5 μg (CFM), Cefepime 30 μg (FEP), Cefotaxime 30 μg (CTX), Cephalexin 30 μg (CL), Caphazolin 30 μg (CZ), Ceftriaxone 30 μg (CRO), Cefoxitin 30 μg (FOX), Piperacillin/Tazobactam 100/10 μg (TZP), Cefuroxime 30 μg (CXM), Cefaclor 30 μg (CEC), Ampicillin/Sulbactam 10/10 μg (SAM), Cefoperazone 75 μg (CFP), Ceftizoxime 30 μg (ZOX), Aztreonam 30 μg (ATM), Meropenem 10 μg (MEM), Imipenem 10 μg (IPM), Kanamycin 30 μg (K), Streptomycin 10 μg (S), Ofloxacin 5 μg (OFX), Norfloxacin 10 μg (NOR), Ciprofloxacin 5 μg (CIP); Gatifloxacin 5 μg (GTX), Chloramphenicol 30 μg (C), Azithromycin 15 μg (AZM), Doxycycline 30 μg (TE), Minocycline 30 μg (MH), Compound Sulfamethoxazole 23.75/1.25 μg (SMZ), and Trimethoprim 5 μg (TMP) (Oxoid, Basingstoke, United Kingdom). The results were interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) breakpoints. Escherichia coli ATCC 25,922 was used as a control for antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Multi-Locus Sequence Typing (MLST)

MLST was performed on three ESBL-producing isolates and seven non-ESBL producing isolates by amplifying the seven standard housekeeping loci gapA, infB, mdh, pgi, phoE, rpoB, and tonB as described previously [43]. Sequence types (STs) were assigned using the online database on the Pasteur Institute MLST website (http://bigsdb.pasteur.fr/klebsiella/klebsiella.html). The MLST profiles were analyzed and compared using BioNumerics version 7.6, created by bioMérieux (Applied Maths NV, St Martens Latem, Belgium). The minimum spanning tree predicted putative relationships among the isolates and recorded the isolates as more closely related when 6 of 7 loci were identical.

Molecular investigations of antimicrobial resistance

The presence of ESBL genes (blaCTX-M, blaTEM, blaSHV, blaGES, blaPER, blaVEB, blaOXA-1, and blaOXA-2); MGEs genes (IS903, IS26, intI1, traA, trbC, tnpU and tnp513); aminoglycoside genes ((aac)-I, aac(6)- I, aac(6')-Ib, ant3'-I, rmtA, rmtB, rmtD, armA, aadA5, and npmA); quinolones genes (qnrA, qnrS, and qnrB); and the blaCTX-M group surrounding regions genes (ISEcpUP-F, IS26-FCJ, CTX-M-1-RCJ) [40] carried by all three ESBL-producing isolates and seven non-ESBL-producing isolates were screened by PCR (Table 1). In addition, sanger methodology was performed by Sangong Biotech (Shanghai, China), and sequence analysis was performed using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) website (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) with the BLAST tool.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study were included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- AMR:

-

Antimicrobial resistance

- ATM:

-

Aztreonam

- AZM:

-

Azithromycin

- C:

-

Chloramphenicol

- CAZ:

-

Ceftazidime

- CEC:

-

Cefaclor

- CFM:

-

Cefixime

- CFP:

-

Cefoperazone

- CIP:

-

Ciprofloxacin

- CL:

-

Cephalexin

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CRO:

-

Ceftriaxone

- CTX:

-

Cefotaxime

- CXM:

-

Cefuroxime

- CZ:

-

Caphazolin

- E. coli :

-

Escherichia coli

- ESBL:

-

Extended-spectrum β-lactamases

- FEP:

-

Cefepime

- FOX:

-

Cefoxitin

- GTX:

-

Gatifloxacin

- HV:

-

Hypermucoviscosity

- IPM:

-

Imipenem

- K:

-

Kanamycin

- K. pneumoniae :

-

Klebsiella pneumoniae

- MEM:

-

Meropenem

- MGEs:

-

Mobile genetic elements

- MH:

-

Minocycline

- MLST:

-

Multilocus Sequence Typing

- MOX:

-

Moxalactam

- NCBI:

-

National Center for Biotechnology Information

- NOR:

-

Norfloxacin

- OFX:

-

Ofloxacin

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PIP:

-

Piperacillin

- S:

-

Streptomycin

- SAM:

-

Ampicillin/Sulbactam

- STs:

-

Sequence types

- SXT:

-

Compound Sulfamethoxazole

- TE:

-

Doxycycline

- TMP:

-

Trimethoprim

- TZP:

-

Piperacillin/Tazobactam

- ZOX:

-

Ceftizoxime

References

Zhan L, Wang S, Guo Y, Jin Y, Duan J, Hao Z, Lv J, Qi X, Hu L, Chen L, Kreiswirth BN, Zhang R, Pan J, Wang L, Yu F. Outbreak by hypermucoviscous Klebsiella pneumoniae ST11 Isolates with carbapenem resistance in a tertiary hospital in China. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:182.

Wang T, Xie Y, Zheng Y, Wang C, Li D, Koehler AV, Gasser R. Parasites of the giant panda: a risk factor in the conservation of a species. Adv Parasitol. 2018;99:1–33.

Geng G. 1864 wild pandas protection in china makes new achievements. Green China. 2015;4:10–2.

Wang Q, Jiang H, Tateko Nakao, Koji Imazu. A case report of giant panda Klebsiella pneumoniae hemorrhagic enteritis. Sichuan J Zool. 1998;17(1):29.

Wang K, Zhang H. Pathological observation of bacterial septicemia in subadult giant panda. Chin J Vet Sci Tech. 2000;30(1):28–9.

Wang C, Lan J, Luo L. Giant panda infectious genitourinary hematuria pathogen-Klebsiella pneumoniae. Sichuan J Zool. 2006;25(01):85-87+204.

Chen Y, Liu S, Su X, Gen Y, Huang W, Chen X, Bai M, Cheng Z. A Case of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus mirabilis Infection in giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca). Chin J Wildlife. 2020;41(04):1013–9.

Bolister NJ, Johnson HE, Wathes CM. The ability of airborne Klebsiella pneumoniae to colonize mouse lungs. Epidemiol Infect. 1992;109(1):121–31.

Amaya E, Reyes D, Vilchez S, Paniagua M, Mollby R, Nord CE, Weintraub A. Antibiotic resistance patterns of intestinal Escherichia coli isolates from Nicaraguan children. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60(Pt 2):216–22.

O’Neill J. Antimicrobial resistance: tackling a crisis for the future health and wealth of nations. London: Review on Antimicrobial Resistance; 2014.

Paterson DL, Bonomo RA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases: a clinical update. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18(4):657–86.

Fuentes-Castillo D, Shiva C, Lincopan N, Sano E, Fontana H, Streicker DG, Mahamat OO, Falcon N, Godreuil S, Benavides JA. Global high-risk clone of extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST307 emerging in livestock in Peru. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2021;58(3):106389.

Hansen SK, Kaya H, Roer L, Hansen F, Skovgaard S, Justesen US, Hansen DS, Andersen LP, Knudsen JD, Røder BL, Østergaard C, Søndergaard T, Dzajic E, Wang M, Samulioniené J, Hasman H, Hammerum AM. Molecular characterization of Danish ESBL/AmpC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae from bloodstream infections, 2018. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2020;22:562–7.

Wang X, Kang Q, Zhao J, Liu Z, Ji F, Li J, Yang J, Zhang C, Jia T, Dong G, Liu S, Hu G, Qin J, Wang C. Characteristics and epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing multidrug-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae from red kangaroo. China Front Microbiol. 2020;11:560474.

Benavides JA, Salgado-Caxito M, Opazo-Capurro A, González Muñoz P, Piñeiro A, Otto Medina M, Rivas L, Munita J, Millán J. ESBL-producing Escherichia coli carrying CTX-M genes circulating among livestock, dogs, and wild mammals in small-scale farms of central Chile. Antibiotics (Basel). 2021;10(5):510.

Sudarwanto M, Akineden Ö, Odenthal S, Gross M, Usleber E. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase (ESBL)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in bulk tank milk from dairy farms in Indonesia. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2015;12(7):585–90.

Liu Y, Yang Y, Chen Y, Xia Z. Antimicrobial resistance profiles and genotypes of extended-spectrum β-lactamase- and AmpC β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from dogs in Beijing. China J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;10:219–22.

Montso KP, Dlamini SB, Kumar A, Ateba CN. Antimicrobial resistance factors of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases producing Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from cattle farms and raw beef in north-west province. South Africa Biomed Res Int. 2019;2019:4318306.

Diab M, Hamze M, Bonnet R, Saras E, Madec JY, Haenni M. OXA-48 and CTX-M-15 extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in raw milk in Lebanon: epidemic spread of dominant Klebsiella pneumoniae clones. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66(11):1688–91.

Koovapra S, Bandyopadhyay S, Das G, Bhattacharyya D, Banerjee J, Mahanti A, Samanta I, Nanda PK, Kumar A, Mukherjee R, Dimri U, Singh RK. Molecular signature of extended spectrum β-lactamase producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated from bovine milk in eastern and north-eastern India. Infect Genet Evol. 2016;44:395–402.

Pepin-Puget L, El Garch F, Bertrand X, Valot B, Hocquet D. Genome analysis of Enterobacteriaceae with non-wild type susceptibility to third-generation cephalosporins recovered from diseased dogs and cats in Europe. Vet Microbiol. 2020;242:108601.

Yamanaka T, Funakoshi H, Kinoshita K, Iwashita C, Horikoshi Y. CTX-M group gene distribution of extended spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae at a Japanese Children’s hospital. J Infect Chemother. 2020;26(9):1005–7.

Beigverdi R, Jabalameli L, Jabalameli F, Emaneini M. Prevalence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: first systematic review and meta-analysis from Iran. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;18:12–21.

Cubero M, Grau I, Tubau F, Pallares R, Dominguez MA, Linares J, Ardanuy C. Molecular epidemiology of klebsiella pneumoniae strains causing bloodstream infections in adults. Microb Drug Resist. 2018;24(7):949–57.

Karlowsky JA, Adam HJ, Baxter MR, Lagacé-Wiens PR, Walkty AJ, Hoban DJ, Zhanel GG. In vitro activity of ceftaroline-avibactam against gram-negative and gram-positive pathogens isolated from patients in Canadian hospitals from 2010 to 2012: results from the CANWARD surveillance study. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(11):5600–11.

Ghafourian S, Bin Sekawi Z, Sadeghifard N, Mohebi R, Kumari Neela V, Maleki A, Hematian A, Rhabar M, Raftari M, Ranjbar R. The prevalence of ESBLs producing Klebsiella pneumoniae Isolates in some major hospitals. Iran Open Microbiol J. 2011;5:91–5.

Zhou W, Zhu L, Jia M, Wang T, Liang B, Ji X, Sun Y, Liu J, Guo X. Detection of multi-drug-resistant Escherichia coli in a giant panda (Ailuropoda melanoleuca) with extraintestinal polyinfection. J Wildl Dis. 2018;54(3):626–30.

Bush K, Jacoby GA. Updated functional classification of beta-lactamases. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2010;54(3):969–76.

Salverda ML, De Visser JA, Barlow M. Natural evolution of TEM-1 β-lactamase: experimental reconstruction and clinical relevance. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2010;34(6):1015–36.

Seiffert SN, Hilty M, Perreten V, Endimiani A. Extended-spectrum cephalosporin-resistant Gram-negative organisms in livestock: an emerging problem for human health? Drug Resist Updat. 2013;16(1–2):22–45.

Ding Y, Saw WY, Tan LWL, Moong DKN, Nagarajan N, Teo YY, Seedorf H. Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase-producing and mcr-1-positive Escherichia coli from the gut microbiota of healthy Singaporeans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2021;87(20):e0048821.

Zhang H, Yang Q, Liao K, Ni Y, Yu Y, Hu B, Sun Z, Huang W, Wang Y, Wu A, Feng X, Luo Y, Chu Y, Chen S, Cao B, Su J, Duan Q, Zhang S, Shao H, Kong H, Gui B, Hu Z, Badal R, Xu Y. Update of incidence and antimicrobial susceptibility trends of Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from Chinese intra-abdominal infection patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17(1):776.

Qiao J, Zhang Q, Alali WQ, Wang J, Meng L, Xiao Y, Yang H, Chen S, Cui S, Yang B. Characterization of extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs)-producing Salmonella in retail raw chicken carcasses. Int J Food Microbiol. 2017;248:72–81.

Poirel L, Nordmann P. Carbapenem resistance in Acinetobacter baumannii: mechanisms and epidemiology. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2006;12(9):826–36.

Lee CR, Cho IH, Jeong BC, Lee SH. Strategies to minimize antibiotic resistance. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(9):4274–305.

Deng J, Li YT, Shen X, Yu YW, Lin HL, Zhao QF, Yang TC, Li SL, Niu JJ. Risk factors and molecular epidemiology of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae in Xiamen. China J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2017;11:23–7.

Xia J, Fang LX, Cheng K, Xu GH, Wang XR, Liao XP, Liu YH, Sun J. Clonal spread of 16S rRNA methyltransferase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae ST37 with high prevalence of ESBLs from companion animals in China. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:529.

Leangapichart T, Lunha K, Jiwakanon J, Angkititrakul S, Järhult JD, Magnusson U, Sunde M. Characterization of Klebsiella pneumoniae complex isolates from pigs and humans in farms in Thailand: population genomic structure, antibiotic resistance and virulence genes. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2021;76(8):2012–6.

Huang YT, Kuo YW, Lee NY, Tien N, Liao CH, Teng LJ, Ko WC, Hsueh PR, SMART study group. Evaluating NG-test CARBA 5 multiplex Immunochromatographic and Cepheid Xpert CARBA-R Assays among carbapenem-resistant Enterobacterales isolates associated with bloodstream infection. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10(1):e0172821.

Davies J, Davies D. Origins and evolution of antibiotic resistance. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2010;74(3):417–33.

Berical AC, Harris D, Dela Cruz CS, Possick JD, Pneumococcal Vaccination Strategies. An update and perspective. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(6):933–44.

Zhao M, Jiang Y, Chen Z, Fan Z, Jiang Y. Traditional Chinese medicine for helicobacter pylori infection: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100(3):e24282.

Diancourt L, Passet V, Verhoef J, Grimont PA, Brisse S. Multilocus sequence typing of Klebsiella pneumoniae nosocomial isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43(8):4178–82.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all of the animal husbandry staff at the CRBGP and James Edward Ayala for the assistance in English editing.

Funding

This research was funded by Sichuan Science and Technology Program (2018JY0363) and Chengdu Giant Panda Breeding Research Foundation (CPF2017-18).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors readed and approved the final manuscript. XS: conceptualization, formal analysis, funding acquisition, methodology, investigation, validation, project administration, resources, writing-original draft, writing-review and editing, project administration; XY: methodology and formal analysis; YL: investigation; DZ: resources; LL: software; FS, YG and CY: methodology; RH: funding acquisition; SL: writing-review and editing.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The methods, use of materials and all experimental procedures involving animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding protocol #2018017. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations under the Law of the People’s Republic of China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Su, X., Yan, X., Li, Y. et al. Identification of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (CTX-M)-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae belonging to ST37, ST290, and ST2640 in captive giant pandas. BMC Vet Res 18, 186 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03276-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-022-03276-7