Abstract

Background

Fourteen-years after the last Rift Valley fever (RVF) virus (RVFV) outbreak, Somalia still suffers from preventable transboundary diseases. The tradition of unheated milk consumption and handling of aborted materials poses a public health risk for zoonotic diseases. Limited data are available on RVF and Brucella spp. in Somali people and their animals. Hence, this study has evaluated the occurrence of RVFV and Brucella spp. antibodies in cattle, goats and sheep sera from Afgoye and Jowhar districts of Somalia.

Methods

Serum samples from 609 ruminants (201 cattle, 203 goats and 205 sheep), were serologically screened for RVF by a commercial cELISA, and Brucella species by modified Rose Bengal Plate Test (mRBPT) and a commercial iELISA.

Results

Two out of 609 (0.3 %; 95 %CI: 0.04–1.2 %) ruminants were RVF seropositive, both were female cattle from both districts. Anti-Brucella spp. antibodies were detected in 64/609 (10.5 %; 95 %CI: 8.2–13.2 %) ruminants by mRBPT, which were 39/201 (19.4 %) cattle, 16/203 (7.9 %) goats and 9/205 (4.4 %) sheep. Cattle were 5.2 and 2.8 times more likely to be Brucella-seropositive than sheep (p = 0.000003) and goats (p = 0.001), respectively. When mRBPT-positive samples were tested by iELISA, 29/64 (45.3 %; 95 %CI: 32.8–58.3 %) ruminant sera were positive for Brucella spp. Only 23/39 (58.9 %) cattle sera and 6/16 (37.5 %) goat sera were positive to Brucella spp. by iELISA.

Conclusions

The present study showed the serological evidence of RVF and brucellosis in ruminants from Afgoye and Jowhar districts of Somalia. Considering the negligence of the zoonotic diseases at the human-animal interface in Somali communities, a One Health approach is needed to protect public health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Rift Valley fever (RVF) and brucellosis are important neglected zoonotic diseases with severe negative economic impact as they affect livestock productivity and survival, and threaten human health [1, 2]. By reducing the productivity of livestock, these diseases significantly lower the quantity and quality of animal products and consequently erode household nutrition, income and food security [3]. In Somalia, livestock represents 60 % of the gross domestic product (GDP) and plays an important role in poverty alleviation [4]. Despite the importance of livestock in the country and the health risk of infectious diseases on people and their animals, epidemiological data on zoonotic diseases are scarce in the country.

Rift Valley fever virus (RVFV) is a zoonotic transboundary vector-borne virus of the genus Phlebovirus in the family Phenuiviridae affecting primarily domestic ruminants and humans [5, 6]. It was first identified in 1931 in the Rift Valley of Kenya [6, 7], and has caused many documented outbreaks in humans and livestock in Africa including Somalia, and in Arabian Peninsula and some Indian Ocean Islands [5]. The RVF is a World Organization for Animal Health (OIE) listed disease due to its potential to cause human illness and deaths, high livestock abortions and deaths, and a setback to international livestock trade [8]. The disease is often linked to persistent heavy rainfall and flooding, which causes the emergence of infected mosquitoes, Aedes spp., which is already infected via transovarial transmission, and thus, lead to spread of the virus to animals and humans [6].

Previous studies have described outbreaks of RVF in Somalia and Kenya [9], and recent data on the seroprevalence of the disease has been described in Ethiopia [10]. However, routine surveillance for RVFV in Sub-Saharan African countries is limited and outbreaks are underreported [6]. A previous study on RVF in Saudi Arabia has found seroprevalence of 22.05 and 8.49 % in sheep and goats imported from Somalia, respectively [11]. However, data on RVF in Southern Somalia is lacking.

Brucellosis is a neglected bacterial zoonotic disease that severely hinders livestock productivity and human health [12, 13]. The disease is caused by Brucella spp., with B. abortus and B. melitensis of particular importance in ruminant and human cases. Transmission from animals to humans occurs mainly through the ingestion of infected dairy products and direct contact with an infected animal [12, 14].

Previous studies on serological evidence of brucellosis throughout sub-Saharan Africa have been reported [15, 16]. However, it remains a neglected disease in Somalia with few data available for ruminants, the majority dated before the Civil War in the country [17,18,19,20]. The reported Brucella spp. prevalence in the country is of 4 % in sheep, 4.9 % in goats [21] and 5.5 % in cattle [19].

After 20 years of crisis, Somalia is still politically unstable, famine and lacking state-of-the-art knowledge on zoonotic diseases. The tropical climate and prevailing tradition of unheated milk consumption, handling of aborted materials and reproductive excretions with bare hands favours disease spread. Herein, we aimed to evaluate the presence of antibodies specific to RVFV and Brucella spp. in cattle, goats and sheep from two important districts of Somalia.

Materials and methods

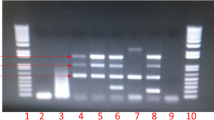

A total of 609 ruminant blood samples (201 cattle, 203 goats and 205 sheep) from Afgoye (2°08′47.67′′N 45°07′08.11′′E) and Jowhar (2°46′38.72′′N 45°30′05.85′′E) districts of Somalia (Fig. 1), collected from November 2017 to February 2018, previously surveyed for other pathogens [22] were evaluated. Blood and serum samples were kept at -20 °C for future studies. Serum samples were screened for RVFV by a commercial cELISA (ID Screen® Rift Valley fever Competition Multi-species, ID.vet, Grabels, France), which detects IgG antibodies specific to the RVFV nucleoprotein (NP) with 91–100 % sensitivity and 100 % specificity [23]. For Brucella spp., serum samples were initially tested by modified Rose Bengal Plate Test (mRBPT) with 89.6 % sensitivity and 84.5 % specificity [24]. The mRBPT positive samples were re-tested by a commercial indirect ELISA (iELISA) (ID Screen® Brucellosis Serum Indirect Multi-species, ID.vet, Grabels, France), which detects the IgG antibodies specific to Brucella Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) antigens with 96.8 % sensitivity and 96.3 % specificity [24]. The surveyed two districts are drained by Shabelle river and have suitable ecological conditions for vector breeding and disease occurrence. The cattle and small ruminants in these districts are kept under an extensive animal husbandry system and are often co-grazed.

Map of Somalia showing the location of blood samples. Sampled regions are highlighted in green (Middle Shabelle) and blue (Lower Shabelle), and the dots indicate the approximate location of the sampled districts (Jowhar and Afgoye). The figure was generated and modified using QGIS software version 2.18.19

Data were compiled and analyzed in Epi Info™ software, version 7.2.3.1 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, CDC, USA). Chi-square test was used to determine the difference between whether individual factors were associated with seropositivity to RVFV and Brucella spp. Odds ratio (OR), 95 % confidence interval and p-values were calculated separately for each variable. Results considered significantly different when p < 0.05.

Results

Two out of 609 (0.3 %; 95 % CI: 0.04–1.2 %) ruminant sera showed positive reaction for RVF N protein, that were adult female cattle from Afgoye or Jowhar districts. Anti-Brucella spp. antibodies were detected in 64/609 (10.5 %; 95 % CI: 8.2–13.2 %) ruminants by mRBPT, which were 9/205 (4.4 %; 95 % CI: 2–8.2 %) sheep, 16/203 (7.9 %; 95 % CI: 4.6–12.5 %) goats and 39/201 (19.4 %; 95 % CI: 14.2–25.6 %) cattle. Cattle were more likely to be seropositive to Brucella spp. than sheep (OR: 5.2; χ2 = 21.9, p = 0.000003) and goats (OR: 2.8; χ2 = 11.4, p = 0.001). Association between districts (p = 0.453) or sex (p = 0.903) and seropositivity to Brucella spp. in ruminants was not found. When mRBPT-positive samples were tested by iELISA, 29/64 (45.3 %; 95 % CI: 32.8–58.3 %) ruminant sera also tested positive for Brucella spp. Only 23/39 (58.9 %) cattle and 6/16 (37.5 %) goat sera were reactive to Brucella spp. LPS antigens by iELISA. The seroprevalence of RVF and Brucella spp. for each variable evaluated is summarized in Table 1.

Discussion

A limited number of studies on neglected zoonotic diseases have been reported in animals and humans in Somalia [22, 25]. Somalia is a livestock-dependent country in East Africa, which borders Kenya and Ethiopia where zoonotic transboundary diseases are often documented [6, 10].

To the best of the author’s knowledge, this is the first study on RVF in cattle, goats, and sheep in Afgoye and Jowhar districts of Somalia. Herein, overall, 1 % cattle were seropositive to RVFV by cELISA, and all goats and sheep tested negative. A previous study has reported high seroprevalence rates of RVFV in sheep (22.05 %, 30/136) and goats (8.49 %, 9/106) imported from Somalia to Saudi Arabia for pilgrimage season in 2011 [11]. It is important to state that neither the origin of the imported animals nor the quarantine status after arriving in Saudi Arabia was specified in that study. It was, therefore, impossible to affirm the origins of those animals. Moreover, a previous study in northern Somalia have found an overall RVF seroprevalence of 2 % in sheep and 5 % in goats sampled in Somaliland in 2001 and in Puntland in 2003 [26]. The last documented RVF outbreak occurred in 2007 in southern Somalia, specifically in the Middle and Lower Juba and Gedo regions both located at the border of Kenya, where the outbreak focus was reported [27].

In the present study, we evaluated ruminant’s serum samples from Afgoye and Jowhar districts, where RVF outbreaks have never been reported, collected between November 2017 to February 2018, which represents the dry season in Somalia [22] and may have influenced the low seropositivity found due to the low survival and proliferation of Aedes spp. Differing, a higher RVF prevalence has been found in sheep and goats from the Nugal Valley, Somaliland, in 2001 [26]. Our results are in line with the RVF findings obtained in Egypt (0 % in goats and 0.46 % in sheep) after 12 years from the last RVF outbreak in that country [28]. Thus, we hypothesize that animals evaluated by Mohamed et al. [11] may be the remnant livestock from the last documented RVFV outbreak in Somalia, which needs to be further investigated. Finally, a recent RVF outbreak has been confirmed in Isiolo, Mandera, Murang’a and Garissa counties of Kenya in February 2021 [29]. Thus, considering that free cattle movement between Kenya and Somalia occurs, RVF cases may also occur in Somalia, mainly during the rainy season.

Herein, the overall 10.5 % ruminants (19.4 % cattle, 7.9 % goats and 4.4 % cheep) were seropositive for Brucella spp. by mRBPT. Similar findings were found in Nigeria [30] and Sudan [31], in which cattle showed higher Brucella spp. seroprevalence rates than sheep and goats. It has been found that the prevalence of brucellosis is higher in pastoral grazing areas than in the urban and peri-urban areas [32]. In the present study, sheep and goats were originally from urban and peri-urban areas of Afgoye and Jowhar districts, which may explain the lower Brucella seroprevalence found. Moreover, previous studies on Brucella spp. in Somali cattle have found low seroprevalence rates of 0.7 % in Benadir region [20] and 5.5 % in Somaliland [19]. Differences in Brucella spp. prevalence may be due to variation in location, husbandry and management system, and serological test used (RBPT x mRBPT) [33]. Differences in the results of the two tests applied herein were due to the higher sensitivity and specificity of the commercial iELISA compared to the mRBPT.

In neighboring countries, such as Kenya, it has been pointed that there is a risk for re-emergence and transmission of brucellosis because of the co-existence of animal husbandry activities and social-cultural activities [34]. In fact, a strong association between human and animal Brucella seropositivity has been reported [35]. In Somalia, along with the same social-cultural activities there is a prevailing tradition of unheated milk consumption and handling of aborted materials and reproductive excretions with bare hands [36]. Thus, there is a risk of human cases of brucellosis particularly in groups occupationally or domestically exposed to those ruminants. Our data highlights the need for a One Health approach in the country aiming to reduce the odds of zoonotic transmission.

Conclusions

The present study provides evidence for the serological prevalence of circulating antibodies against RVFV and Brucella spp. in ruminants in Somalia. Considering the negligence of the zoonotic diseases at the human-animal interface in Somali communities, there is a need to promote the One Health concept among multi-sectoral professionals and decision-makers for better and sustainable integrated health development and implementing effective control strategies against these zoonotic diseases.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ARTC:

-

Abrar Research and Training Centre

- AU:

-

Abrar University

- Brucella LPS:

-

Brucella Lipopolysaccharide

- CDC:

-

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- cELISA:

-

Competitive Enzyme Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay

- CI:

-

confidence interval

- CNPq:

-

Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico

- GDP:

-

Gross Domestic Product

- GOHi:

-

Global One Health initiative

- iELISA:

-

indirect ELISA

- IsDB:

-

Islamic Development Bank

- mRBPT:

-

modified Rose Bengal Plate Test

- OIE:

-

World Organization for Animal Health

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RVF:

-

Rift Valley fever

- RVFV:

-

RVF virus

- RVFV NP:

-

RVFV nucleoprotein

- TWAS:

-

The World Academy of Sciences

- UFPR:

-

Universidade Federal do Paraná

- UNESCO:

-

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization

- VBDL:

-

Vector-Borne Diseases Laboratory

References

Ibrahim M, Schelling E, Zinsstag J, Hattendorf J, Andargie E, Tschopp R. Seroprevalence of brucellosis, Q-fever and Rift Valley fever in humans and livestock in Somali Region, Ethiopia. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2021, 15(1): e0008100. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0008100

Kanouté, Y. B., Gragnon, B. G., Schindler, C., Bonfoh, B., & Schelling, E. Reprint of “Epidemiology of brucellosis, Q Fever and Rift Valley Fever at the human and livestock interface in northern Côte d’Ivoire.” Acta Tropica, 2017, 175, 121–129. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2017.08.013

FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization. Improved animal health for poverty reduction and sustainable livelihoods. FAO, Animal production and health. 2002, paper 153. ISBN 92-5-104757-X. http://www.fao.org/3/y3542e/y3542e00.htm.

FAO – Food and Agriculture Organization. Somalia, towards a Livestock Sector Strategy. Final Report. Report No. 04/001 IC-SOM. FAO, World Bank Cooperative Programme. European Union, 2004, 1–170.

Paweska JT. Rift Valley fever. Rev. Sci. Tech. Off. Int. Epiz., 2015, 34(2), 375–389 doi:https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.34.2.2364.

Clark MHA, Warimwe GM, Di Nardo A, Lyons NA, Gubbins S. Systematic literature review of Rift Valley fever virus seroprevalence in livestock, wildlife and humans in Africa from 1968 to 2016. PLoS Negl Trop Dis, 2018, 12(7): e0006627. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006627

Daubney R, Hudson JR, Garnham PC. Enzootic hepatitis or rift valley fever. An undescribed virus disease of sheep cattle and man from East Africa. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1931;34(4):545–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/path.1700340418.

OIE. Terrestrial Animal Health Code Chapter 8.15. Infection with Rift Valley fever virus. OIE, 2019, Vol.1, 1-4. Available from https://www.oie.int/fileadmin/Home/eng/Health_standards/tahc/current/chapitre_rvf.pd Accessed 25 February 2021.

Himeidan YE, Kweka EJ, Mahgoub MM, El Rayah EA, Ouma JO. Recent outbreaks of rift valley fever in East Africa and the Middle East. Front Public Health. 2014; 2. 1–11 doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2014.00169

Asebe G, Mamo G, Michlmayr D, Abegaz WE, Endale A, Medhin G, Larrick JW, Legesse M. Seroprevalence of Rift Valley Fever and West Nile Fever in Cattle in Gambella Region, South-West Ethiopia. Vet Med (Auckl), 2020, 19;11:119–130. doi: https://doi.org/10.2147/VMRR.S278867

Mohamed AM, Ashshi AM, Asghar AH, Abd El-Rahim IH, El-Shemi AG, Zafar T. Seroepidemiological survey on Rift Valley fever among small ruminants and their close human contacts in Makkah, Saudi Arabia, in 2011. Rev Sci Tech. 2014; 33(3):903–15. doi: https://doi.org/10.20506/rst.33.3.2328.

Franc, K. A., Krecek, R. C., Häsler, B. N., & Arenas-Gamboa, A. M. Brucellosis remains a neglected disease in the developing world: a call for interdisciplinary action. BMC Public Health, 2018, 18(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-5016-y

Khurana SK, Sehrawat A, Tiwari R, Prasad M, Gulati B, Shabbir MZ, Chhabra R, Karthik K, Patel SK, Pathak M, Iqbal Yatoo M, Gupta VK, Dhama K, Sah R, Chaicumpa W. Bovine brucellosis - a comprehensive review. Vet Q. 2021; 41(1):61–88. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01652176.2020.1868616.

Christopher S, Umapathy BL, Ravikumar KL. Brucellosis: review on the recent trends in pathogenicity and laboratory diagnosis. J Lab Physicians. 2010; 2(2):55–60. doi: https://doi.org/10.4103/0974-2727.72149.

Ducrotoy M, Bertu WJ, Matope G, Cadmus S, Conde-Álvarez R, Gusi AM, Welburn S, Ocholi R, Blasco JM, Moriyón I. Brucellosis in Sub-Saharan Africa: Current challenges for management, diagnosis and control. Acta Trop. 2017; 165:179–193. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2015.10.023.

McDermott JJ, Arimi SM. Brucellosis in sub-Saharan Africa: epidemiology, control and impact. Vet Microbiol. 2002;90(1–4):111–34. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/s0378-1135(02)00249-3.

Falade S and Hussein AH. Brucella Sero-Activity in Somali Goats. Trop Anim Health Prod, 1979, 11, 211–212. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02237804

Andreani E., Prosperi S, Salim AH and Arush AM. Serological and bacteriological investigation on brucellosis in domestic ruminants of the Somali Democratic Republic. Rev. Elev. Med. Vet., 1982, 35; 329–333.

Ghanem YM, El-Sawalhy A, Saad AA, Abdelkader AH and Heybe A. A serosurvey of Bovine Brucellosis in three cattle-rearing regions of Somaliland (Northern Somalia). Bull Anim Health and Prod Afr, 2009, 57, 221–232.

Mohamud AI, Mohamed YA and Mohamed MI. Sero-prevalence and associated risk factors of bovine brucellosis in selected districts of Benadir Region, Somalia. Journal of Istanbul Veterinary Sciences. 2020, 4(2), 57–63.

Ghanem YM, El-Sawalhy A, Saad AA, Abdelkader AH and Heybe A. A Seroprevalence Study of Ovine and Caprine Brucellosis in Three Main Regions of Somaliland (Northern Somalia). Bull Anim Health and Prod Afr, 2009, 57, Pp. 233–244.

Hassan-Kadle AA, Ibrahim AM, Nyingilili HS, Yusuf AA, Vieira RFC (2020). Parasitological and molecular detection of Trypanosoma spp. in cattle, goats and sheep in Somalia. Parasitology, 2020, 147, 1786–1791. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S003118202000178X

Kortekaas J, Kant J, Vloet R, Cêtre-Sossah C, Marianneauc P, Lacotec S, Banyard AC et al. 2013, ‘European ring trial to evaluate ELISAs for the diagnosis of infection with Rift Valley fever virus’, J Virol Methods, 2013;187(1), 177–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jviromet.2012.09.016

Getachew T, Getachew G, Sintayehu G, Getenet M, Fasil A. Bayesian estimation of sensitivity and specificity of Rose Bengal, complement fixation, and indirect ELISA tests for the diagnosis of bovine brucellosis in Ethiopia. Vet Med Int. 2016;1–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2016/8032753.

Hassan-Kadle AA. A Review on Ruminant and Human Brucellosis in Somalia. Open J Vet Med, 2015, 5, 133–137. doi: https://doi.org/10.4236/ojvm.2015.56018

Soumare B, Tempia S, Cagnolati V, Mohamoud A, Van Huylenbroeck G, Berkvens D. Screening for Rift Valley fever infection in northern Somalia: a GIS based survey method to overcome the lack of sampling frame. Vet Microbiol. 2007, 15;121(3–4):249–56. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2006.12.017.

Nderitu L, Lee JS, Omolo J, Omulo S, O’Guinn ML, Hightower A, Mosha F, Mohamed M, Munyua P, Nganga Z, Hiett K, Seal B, Feikin DR, Breiman RF, Njenga MK. Sequential Rift Valley fever outbreaks in eastern Africa caused by multiple lineages of the virus. J Infect Dis. 2011, 1;203(5):655 – 65. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/infdis/jiq004.

Mroz C, Gwida M, El-Ashker M, El-Diasty M, El-Beskawy M, Ziegler U, Eiden M, Groschup MH. Seroprevalence of Rift Valley fever virus in livestock during inter-epidemic period in Egypt, 2014/15. BMC Vet Res. 2017, 5;13(1):87. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-0993-8.

World Health Organization (2021). Rift Valley Fever – Kenya. Available at https://www.who.int/csr/don/12-february-2021-rift-valley-fever-kenya/en/ Accessed 01 March 2021.

Cadmus SIB, Ijabone IF, Oputa HE, Adesoken HK, Stack JA. Serological survey of brucellosis in livestock animals and workers in Ibadan Nigeria. Afr J Biomed Res. 2006;9:163–8.

Mokhtar MO, Abdelhamid AA, Sarah MAA, Abbas MA. Survey of brucellosis among sheep, goats, cattle and camel in Kassala area, Eastern Sudan. J Anim Vet Adv. 2007;6:635–7.

Nguna J, Dione M, Apamaku M, et al. Seroprevalence of brucellosis and risk factors associated with its seropositivity in cattle, goats and humans in Iganga District, Uganda. Pan Afr Med J. 2019;33:99. doi:https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2019.33.99.16960

Dean AS, Bonfoh B, Kulo AE, Boukaya GA, Amidou M, Hattendorf J, Pilo P, Schelling E. Epidemiology of brucellosis and q Fever in linked human and animal populations in northern togo. PLoS One, 2013, 12;8(8):e71501. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0071501.

Njeru J, Wareth G, Melzer F, Henning K, Pletz MW, Heller R, Neubauer H. Systematic review of brucellosis in Kenya: disease frequency in humans and animals and risk factors for human infection. BMC Public Health. 2016 Aug 22;16(1):853. doi: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3532-9.

Osoro EM, Munyua P, Omulo S, Ogola E, Ade F, Mbatha P, et al. Strong association between human and animal Brucella seropositivity in a linked study in Kenya, linked study in Kenya, 2012–2013. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(2):224–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.15-0113.

Kadle AAH, Mohamed SA, Ibrahim AM and Alawad MF. Seroepidemiological study on camel brucellosis in Somalia. Eur Acad Res, 2017; 5(6):2925–42.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ministry of Livestock, Forestry and Range, Somalia for the donation of ELISA kits. Dr. Ahmed A. Hassan-Kadle acknowledges The World Academy of Sciences (TWAS), UNESCO and Islamic Development Bank (IsDB) for their support through IsDB-TWAS postdoctoral fellowship programme in Sustainability Sciences (grant no. 15/2020) at the Universidade Federal do Paraná, Brazil. The Brazilian National Council of Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) provided a fellowship of research productivity (PQ) to Dr Rafael Vieira (CNPq − 313161/2020-8).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AAHK and AMI designed the study. AAHK and AAY collected the data. AAHK, AMO, MAS, OMA, AAY, AMI and RFCV carried out the methodology. AAHK, AMO and RFCV performed the data analysis. AAHK, AMO, and RFCV drafted the manuscript. All authors edited and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the ethical committee of Abrar University, Somalia (reference number AU/ARTC/EC/04/2017). Cattle, goats and sheep owners gave consent to sample their animals. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hassan-Kadle, A.A., Osman, A.M., Shair, M.A. et al. Rift Valley fever and Brucella spp. in ruminants, Somalia. BMC Vet Res 17, 280 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-021-02980-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-021-02980-0