Abstract

Background

Primary ureteral neoplasia in dogs is extremely rare. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the second documented case of a primary ureteral hemangiosarcoma. This case report describes the clinical and pathological findings of a primary distal ureteral hemangiosarcoma.

Case presentation

A 12-year-old spayed female goldendoodle was presented with a history of polyuria and weight loss. Abdominal radiographs revealed a large cranial abdominal mass. Abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) identified a left sided distal ureteral mass with secondary hydroureter and a left lateral hepatic mass with no evidence of connection or diffuse metastasis. A left ureteronephrectomy, partial cystectomy, and left lateral liver lobectomy were performed. Histopathology was consistent with primary ureteral hemangiosarcoma and a hepatocellular carcinoma. Adjunctive therapy including chemotherapy was discussed but declined.

Conclusion

Due to its rarity, the authors of this case presentation believe that ureteral hemangiosarcoma should be included as a differential diagnosis when evaluating a ureteral mass. With the unknown, and suspected poor prognosis, routine monitoring with adjunctive therapy should be considered.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Primary ureteral neoplasia in dogs is extremely rare [1, 2]. This case report describes the clinical and pathological findings of a primary distal ureteral hemangiosarcoma. Previous malignant and benign cases of ureteral neoplasia have been reported, including transitional cell carcinoma, fibroepithelial polyps, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, spindle cell sarcoma, and hemangiosarcoma [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, this is the second documented case of a primary ureteral hemangiosarcoma [9].

Case presentation

A 12-year-old, 23 kg, spayed female Golden Doodle; that was privately owned was presented for evaluation of a large cranial abdominal mass as well as a firm caudal abdominal mass. Historical clinical signs included polyuria and progressive weight loss for 1–2 months. Biochemistry performed through the primary care veterinarian revealed an elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 2181 U/L (reference range: 20 to 150 U/L), and an elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 303 U/L (reference range: 10 to 118 U/L). Radiographs and ultrasound indicated there was a large cranial abdominal mass suspected to be associated with the liver and a second caudal abdominal mass with an unknown origin that appeared to be compressing the urinary bladder.

On presentation, the dog was bright, alert, and responsive. Body condition score was 4/9. The patient was non-painful on abdominal palpation. Abdominal palpation revealed a cranial abdominal mass effect as well as a firm irregular caudal abdominal mass. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable. Hematology was unremarkable. The serum biochemistry revealed an elevated alkaline phosphatase (ALP) of 2102 U/L (reference range: 20 to 150 U/L), and an elevated alanine aminotransferase (ALT) of 299 U/L (reference range: 10 to 118 U/L). Urine analysis demonstrated 3 + protein, with a urine specific gravity of 1.050. A coagulation profile was performed, which was unremarkable. Three-view thoracic radiographs did not show any signs of metastasis or any other significant abnormalities.

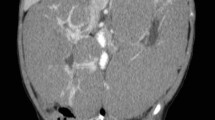

An abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a well-defined, irregularly marginated, multilobulated, hypoattenuating mass, measuring 4.7 cm x 6.8 cm x 8 cm, at the level of the left distal ureter and ureteral papilla, with secondary severe left proximal ureteral dilation, measuring 0.5–0.6 cm (Fig. 1). The cranial abdomen revealed a well marginated, mildly heterogenous, contrasting soft tissue attenuating mass, measuring 6.3 cm x 12.5 cm x 10.9 cm, arising from the caudal aspect of the left lateral liver lobe (Fig. 2).

Dorsal (a) and transverse (b) reconstructed postcontrast, soft tissue algorithm, computed tomography images of the abdomen. Hydroureter (*) secondary to an expansile obstructive mass (short arrow) of the left ureter is visible as well as an attenuating mass of the left lateral liver lobe (long arrow)

An exploratory celiotomy was performed. The celiotomy identified a large mottled mass, measuring 18 cm x 10 cm x 4 cm associated with the left lateral liver lobe (Fig. 3), along with a firm, nodular, multilobular mass, measuring 8 cm x 5 cm, associated with the distal left ureter attached to the left aspect of the urinary bladder (Fig. 4) with proximal ureteral dilation. A left lateral liver lobectomy was performed with a TA-55 stapler and the Ligasure Precise vessel sealing device. The left ureter mass was dissected out and found to be adhered to the bladder serosa and found to enter the bladder lumen through the left ureteral papilla. A left sided ureteronephrectomy and partial cystectomy were performed to remove the mass en bloc. No other abnormalities were noted on final exploration. The patient underwent a successful and uneventful recovery and was discharged from the hospital three days postoperatively. Adjunctive therapy including chemotherapy was discussed but declined. At the initial postoperative evaluation (12 days), the owner reported no overt issues and improvement in appetite and energy, with no abnormalities noted on physical exam. At subsequent evaluations (30-days, 40-days and 120-days), the patient is reported to show consistent and progressive status improvement with no concerns.

Histopathology was performed by a board-certified pathologist and confirmed by a second pathologist. The ureteral mass was narrowly excised with 0.1 mm surgical margins. Histologic findings of the ureteral mass (Fig. 5) revealed a densely cellular, poorly demarcated (Fig. 6), unencapsulated, infiltrative, variably cystic, and hemorrhagic mass which variably borders foci of marked hemorrhage, fibrin, edema, and necrosis. The cells are plump and spindloid, with indistinct cellular borders and wispy eosinophilic cytoplasm (Fig. 7). The nuclei are oval to elongate, with finely stippled to vesicular chromatin and one to three nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are moderate, with a mitotic count of 6 in ten 400x fields. Immunohistochemistry was then performed revealing positive CD31 staining of the neoplastic spindle cells confirming ureteral hemangiosarcoma (Fig. 8).

Histologic findings of the liver mass revealed a densely cellular, poorly demarcated, unencapsulated, infiltrative, variably hemorrhagic, and necrotic mass (Fig. 9). The cells form coalescing broad hepatic cords and trabeculae, supported by a small amount of fibrovascular stroma (Fig. 10). Portal areas and central veins are not discernible within the mass. The cells are polygonal, with distinct cellular borders and a moderate to abundant amount of granular eosinophilic cytoplasm, which variably contains ill-defined vacuolar regions of clearing. The nuclei are round to oval with finely stippled chromatin and one to four nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are moderate, and 11 mitotic figures are observed in ten 400x fields. The findings observed were confirmed to be consistent with hepatocellular carcinoma.

Discussion and conclusion

Ureteral neoplasia is rare in dogs with the majority of tumors being benign [1, 10]. There is only one other recent documented case of ureteral hemangiosarcoma located in the proximal ureter [9]. Previously reported ureteral tumors include leiomyosarcoma, fibroepithelial polyps, fibropapilloma, transitional cell carcinoma, mast cell tumors, giant cell sarcoma and leiomyoma [2, 4, 6, 8, 11,12,13,14,15]. Hemangiosarcoma is a well-known malignant tumor originating from vascular endothelial cells [2, 9, 16, 17]. The most common primary sites reported for hemangiosarcoma include the spleen, right atrium, liver, and skin (particularly the dermis and subcutis) [9, 17, 18]. The canine urinary tract being a primary site of hemangiosarcoma is extremely rare [9, 19, 20]. Previous reports of hemangiosarcoma originating from the urinary tract were localized to the retroperitoneal space, kidney, urethra, prostate, and proximal ureter [9, 21,22,23,24,25].

In this case report, abdominal CT confirmed the presence of a distal ureteral mass with secondary hydroureter. As in people, distal ureteral masses in dogs are more likely to be malignant, whereas proximal ureteral masses are more likely to benign [4, 9, 12, 26, 27]. The histopathology results in this case report of malignant tumor of the distal ureter are supported by these previous findings.

Clinical signs of a ureteral mass may include polyuria, polydipsia, hematuria, urinary incontinence, abdominal pain, lethargy, weight loss, and anorexia [6, 9,10,11]. Clinical signs present with this case included only weight loss and polyuria. Unlike the previous case report of ureteral hemangiosarcoma [9], our patient was not noted to have hematuria. The vague clinical signs associated with a ureteral mass are broad and may be attributed to a multitude of different diseases, warranting a complete and thorough diagnostic evaluation as necessary for an accurate diagnosis [9].

Similar to the previously documented case of ureteral hemangiosarcoma, our patient’s pre-operative thoracic radiographs did not reveal any signs of metastatic disease indicating our patient was a suitable candidate for an exploratory celiotomy [9]. Treatment options for a ureteral mass commonly include surgical resection, specifically by ureteroneocystostomy or ureteronephrectomy [6, 9, 28, 29].

The literature reveals a range in prognosis associated with malignant ureteral masses, which are dependent upon the type of cancer [3, 7, 10, 14]. In the previously documented case of ureteral hemangiosarcoma, the patient was euthanized 40 days post-operatively due to dyspnea secondary to pulmonary metastasis [9]. In the presented case, the 40-day postoperative evaluation revealed consistent and progressive improvement in status, with no overt issues noted on the owners report. Unfortunately, due to the lacking existing evidence of prognosis and prognostic factors attributable to ureteral hemangiosarcoma, authors cannot predict the outcome of our patient, nor provide any extrapolations for future cases.

This case marks only the second documented case of ureteral hemangiosarcoma in canines. Due to its rarity, various clinical signs, and suspected poor prognosis, the authors of this case presentation believe that ureteral hemangiosarcoma should be included as a differential diagnosis when evaluating all ureteral masses despite the presence of hematuria. Currently, ureteral hemangiosarcoma has an unknown and suspected poor long term prognosis [9]. Routine monitoring with the addition of chemotherapy should be considered.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

References

Johnston SA, Karen M, Tobias. (2018) Ureters. In: Textbook of Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal. Elsevier, 115; 5953–5967.

Kudning ST. and Séguin Bernard. (2012) Interventional radiology. In: Textbook of Veterinary Surgical Oncology. Wiley-Blackwell, 3;43–44.

Berzon JL. Primary leiomyosarcoma of the ureter in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1979;175:374–6.

Burton CA, Day MJ, Hotston Moore A, Holt PE. Ureteric fibroepithelial polyps in two dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 1994;35:593–6.

Font A, Closa JM, Mascort J. (1993) Ureteral leiomyoma causing abnormal micturition in a dog. Journal of the American Animal Hospital Association (1):25–27.

Guilherme S, Polton G, Bray J, Blunden A, Corzo N. Ureteral spindle cell sarcoma in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2007;48(12):702–4.

Hanika C, Rebar AH. Ureteral transitional cell carcinoma in the dog. Vet Pathol. 1980;17:643–6.

Liska WD, Patnaik AK. Leiomyoma of the ureter of a dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1977;13:83–4.

Troiano D, Zarelli M. Multimodality imaging of primary ureteral hemangiosarcoma with thoracic metastasis in an adult dog. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2017;00:1–4.

Deschamps JY, Roux FA, Fantinato M, Albaric O. Ureteral sarcoma dog. Journal of Small Animal Practice. 2007;48:699–701.

Farrell M, Philbey AW, Ramsey I. Ureteral fibroepithelial polyp in a dog. J Small Anim Pract. 2006;47:409–12.

Hattel AL, Diters RW, Snavely DA. Ureteral fibropapilloma in a dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1986;188:873.

Linden D, Liptak JM, Vinayak A, et al. Outcomes and prognostic variables associated with primary abdominal visceral soft tissue sarcomas in dogs: A Veterinary Society of Surgical Oncology retrospective study. Vet Comp Oncol. 2019;17(3):265–70.

Steffey M, Rassnick KM, Porter B, NJAA BL. Ureteral mast cell tumor in a dog. Journal of the American Hospital Association. 2004;40:82–5.

Rigas JD, Smith TJ, Gorman ME, Valentine BA, Simpson JM, Seguin B. Primary ureteral giant cell sarcoma in a Pomeranian. Vet Clin Pathol. 2012;41(1):141–6.

Clifford CA, Mackin AJ, Henry CJ. Treatment of Canine Hemangiosarcoma: 2000 and Beyond. J Vet Intern Med. 2000;14(5):479–85.

Mellanby RJ, Chantrey JC, Baines EA, Ailsby RL, Herrtage ME. Urethral haemangiosarcoma in a boxer. J Small Anim Pract. 2004;45(3):154–6.

Kim JH, Graef AJ, Dickerson EB, Modiano JF. (2015) Pathobiology of Hemangiosarcoma in Dogs: Research Advances and Future Perspectives. Vet Sci. 2015;2(4):388–405.

Hill TP, Lobetti RG, Schulman M. Vulvovaginectomy and non-urethrostomy for treatment of hemangiosarcoma of the vulva and vagina. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 2000;71:256–9.

Marolf A, Specht A, Thompson M, Castelman W. Imaging diagnosis: penile hemangiosarcoma. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2006;34:870–8.

Brown NO, Patnaik A, MacEwen EG. Canine hemangiosarcoma: retrospective analysis of 104 cases. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 1985;186:56–8.

Fukuda S, Kobayashi T, Robertson ID, et al. Computed tomography features of canine nonparenchymal hemangiosarcoma. Vet Radiol Ultra- sound. 2014;55(4):374–9.

Hayden DW, Bartges JW, Bell FW, Klausner JS. Prostatic hemangiosarcoma in a dog: clinical and pathological findings. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1992;4:209–11.

Tarvin G, Patnaik A, Greene R. Primary urethral tumors in dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1978;172:931–3.

Locke JE, Barber LG. Comparative aspects and clinical outcomes of canine renal hemangiosarcoma. J Vet Intern Med. 2006;20(4):962–7.

Reichle JK, Peterson RA, 2nd & Barthez PY. (2001) Ureteral neoplasia in dogs. Proceedings of the Annual Conference of the American College of Veterinary Radiology. August 5 to 10, Honolulu, HI.

Reichle JK, Peterson RA, Mahaffey MB, Schelling CG, Barthez PY. Ureteral fibroepithelial polyps in four dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2003;44:433–7.

Berent AC, Weisse C, Bagley D. (2007). Ureteral stenting for benign and malignant disease in dogs and cats (abstr). Vet Surg.

Kulkarni R, Bellamy E. Nickel-titanium shape memory alloy Memokath 051 ureteral stent for managing long-term ureteral obstruction: 4-year experience. J Urol. 2001;166(5):1750–4.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JP assisted with procedure. EM performed the procedure. EE performed the histologic examination. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Consent to use the patient was obtained by the owners

Consent for publication

Not applicable

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest related to this report

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Polit, J.A., Moore, E.V. & Epperson, E. Primary Ureteral Hemangiosarcoma in a dog. BMC Vet Res 16, 386 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02609-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-020-02609-8