Abstract

Background

To understand and reduce the concomitant effects of trapping and handling procedures in wildlife species, it is essential to measure their physiological impact. Here, we examined individual variation in stress levels in non-anesthetized European roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), which were captured in box traps and physically restrained for tagging, biometrics and bio-sampling. In winter 2013, we collected venous blood samples from 28 individuals during 28 capture events and evaluated standard measurements for stress (heart rate, body temperature, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio, lactate and total cortisol). Additionally, we assessed stress using the immunological tool, Leukocyte Coping Capacity (LCC), a real-time proxy for stress measuring oxygen radical production by leukocytes. Finally, the behavioral response to handling was recorded using a scoring system.

Results

LCC and therefore stress levels were negatively influenced by the time animals spent in the box trap with human presence at the capture site prior to handling. In contrast, none of the classical stress measures, including total cortisol, nor the behavioral assessment, were correlated with the stressor tested (time of human presence prior to handling) and thus did not provide a clear depiction regarding the extent of the animals short-term stress response.

Conclusions

Overall our study verifies the LCC as a strong method to quantify short-term stress reactions in wildlife. Moreover, our results clearly show that human presence at the trapping site prior to handling should be kept to an absolute minimum in order to reduce stress levels.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

With the growing complexity of anthropogenic environments, the general demands on wildlife management and conservation are constantly increasing [1, 2]. These fields often include captures and it is important to evaluate the animal welfare implications and to verify that the methods used have not affected the quality of the resulting scientific data [3, 4]. Animal welfare is mostly defined as the well-being of animals and is closely linked to the capability of the individual to cope with sudden situations or changes in its environment [5]. If an animal has difficulties to adapt or is not able to cope with the prevalent situation, it becomes stressed [6]. Stress levels, however, are not only relevant in terms of animal welfare, but also bias various physiological and behavioral measures [7]. In order to increase animal welfare and data quality it is essential to assess and quantify how management and research interventions (i.e. capture and handling) affect stress levels [8]. Stress-responses in vertebrates are primary mediated via two neuro-endocrine regulatory systems, stimulating physiological adaption and behavior. First, the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) produces immediate responses such as the fight or flight response. Activation of the SNS triggers the release of catecholamines within milliseconds after onset of a stressor [9]. Second, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis responds and controls the secretion of glucocorticoids. This response is slower (within minutes) and acts on many metabolic and physiological regulatory systems to keep essential bio-regulatory mechanisms within a certain range [10, 11].

Despite extensive research, stress remains a problematic concept because stress reactions are multidimensional and context dependent [12]. Additionally, stress responses display a large individual variation [9], are influenced by season as well as time of day [13] and are caused by a great variety of stressors [14]. Consequently, stress reactions are difficult to measure and assess, particularly with small sample sizes as it is often the case in field studies [15].

Currently stress responses are assessed by various techniques [16,17,18]. Previous work on wildlife species has focused mainly on glucocorticoid concentrations to define stress [19]. It becomes increasingly apparent, however, that this approach could be misleading due to the wide array of factors influencing the release and efficiency of glucocorticoids [20, 21]. Additionally, there is evidence that they are not stress hormones per se, but rather anti-stress hormones promoting recovery from stress reactions [10, 22]. Therefore, the use of glucocorticoids as a single biomarker for measuring stress is questionable, especially when assessing short-term stress reactions [12, 23]. Furthermore, alongside other classical stress parameters including heart rate and body temperature, which are viable indicators for stress [24, 25], alterations in behavior have been used to determine stress levels in free-ranging wildlife [26]. However, also the behavioral approach is under scientific debate, as the source of the underlying physiological responses are problematic [27]. Hence, there is a need for new, practical tools linking and complementing classical stress parameters towards a more comprehensive description and interpretation of stress responses.

There is growing evidence of the effects of stress on parts of the innate immune system [28,29,30] indicating that it is possible to quantify stress by directly measuring immune responses [31, 32]. White blood cells, more specifically neutrophil granulocytes, of stressed individuals show a substantially decreased capacity to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) compared to less stressed animals. Applying the technique called Leukocyte Coping Capacity (LCC) facilitates a quantitative assessment of stress responses by measuring neutrophil ROS production in real time [31, 33].

In the present study, we tested the validity of LCC together with several classical key stress parameters (heart rate, body temperature, neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio (N:L), lactate, total cortisol and animal behavior), to quantify the short-term stress of capture in one of the most intensively managed [34] free-ranging wild ungulates in Europe, the European roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). Moreover, we investigated whether LCC measures could be linked to these classical and commonly used stress parameters.

We hypothesized that, in contrast to classical stress parameters, the LCC technique facilitates a clear and quantitative assessment of stress in roe deer. Here we tested human presence at the capture site prior to handling as the stress eliciting factor (see Methods). We predicted that (i) LCC will allow to quantify the extent of the stress reaction caused by this stressor [31, 33] and (ii) individuals experiencing high stress levels will exhibit a lower LCC compared to less stressed individuals. Further, we predicted that (iii) due to large individual variation neither the behavior of the animals nor classical stress measures (heart rate, body temperature, N:L ratio, lactate, total cortisol) will reflect the magnitude of short-term stress accurately [20, 21, 27]. However, regarding a possible link between classical stress parameters and LCC we expected that stressed individuals with elevated classical stress parameters would have a low LCC. In short, LCC would be negatively correlated with classical stress proxies.

Methods

Definition of stress and stressor

In this study we defined the situation of being trapped in combination with human presence at the capture site as the stressor of interest eliciting a short-term stress response [9]. The activation of both stress axes and the associated physiological changes are referred to as stress.

Study area and data collection

The study was conducted at the Grimsö Wildlife Research Area (GWRA, 130 km2) in southcentral Sweden (59°40′N, 15°25′E). The predominant landscape is commercially managed coniferous forest (for details see [35]).

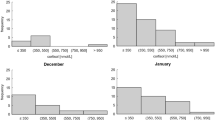

The roe deer population of this area has been intensively studied since 1973 [35] with >3500 captures carried out for various research studies and monitoring purposes. To assess stress reactions in the context of these capture events, where animals are handled without the use of anesthetics, 28 capture events of 28 individuals (18 females, 10 males) were included in this study. Captures took place in winter 2013, in two sampling periods (January 17th – January 30th and March 4th – March 24th). These periods did not overlap with the phase of rutting, parturition [36], or male territoriality [37]. Animals were caught using box traps (L6 Rådjursfälla M/Öster Malma, dimensions: 130 × 62.5 cm and 100 cm high), baited with pelleted forage produced for semi-domesticated reindeer (Rangifer tarandus tarandus) (Renfor, Lantmännen, Nyköping, Sweden). Every trapping site was equipped with two traps which were set in the evenings and checked early the next morning. The front of the trap was closed with wooden bars enabling the animals to see their conspecifics next to the trap. The hatch and sidewall of traps were closed with Masonite® plates blocking visual contact with approaching humans. However, the trapped animal could potentially hear or smell an approaching person. Traps were placed at varying distances from the road (<200 m), but all were visible from the road. In rare cases two individuals were caught at the same trapping site leading to a prolonged time span of human presence prior to handling for the second animal. We recorded the timespan between the arrival at the trapping site by car (on the road) until the start of the actual handling procedure to account for the human presence prior to handling and a potential further onset of a stress response.

Animals were removed from the trap and physically restrained in lateral recumbency on the ground during handling and marking. Once restrained, body temperature and heart rate were measured and a blood sample was obtained immediately (see below). Subsequently, morphological measures were taken and the animals were sexed and weighed.

Additionally, individual behavior was assessed during handling and upon release. Handling behavior was evaluated based on resistance to handling and vocalization of the animal, with scores ranging from 0 (calm, displaying no resistance) to 4 (extreme resistance and almost impossible to handle) (Table 1). Behavior upon release was assessed with scores from 0 to 2, relating to flight speed and the number of intermediate stops (Table 1). The behavioral observation was performed continuously by the same experienced person (L. Jäderberg, >2500 captures). To avoid adverse effects due to physical restraint during the handling procedure of the non-anesthetized animals [38, 39], handling time was minimized. All deer were physically examined by a veterinarian and appeared healthy.

Blood sampling

Blood samples were taken from the jugular vein in <7 min after animals were taken out of the trap. Evacuated tubes (BD Vacutainer®, BD Diagnostics, Preanalytical Systems, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) were used with one 6-ml ethylenediaminetetra-acetic acid (EDTA) (potassium), one 4 ml sodium-heparin tube and four 9-ml serum or gel serum separator tubes. From EDTA samples standard hematological parameters (for details see Additional file 1: Table S1) were analyzed within 24 h of collection. Serum for blood chemistry was separated within 2 h of collection by centrifugation at 1500 x G for 10 min and stored in cryogenic vials (Nalgene, Nalgene Company, Rochester, New York, USA) at −20 °C. Total cortisol levels of all individuals were measured from these serum samples. All samples were analyzed within 3 months of storage (Additional file 2: Table S2) at the Clinical Chemistry Laboratory, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden. Lactate levels were measured from EDTA blood samples within 15 min after collection using the portable Lactate Pro® lactate analyzer (KBK, Arkray, Japan).

LCC measurements

To measure unstimulated blood chemiluminescence levels, providing information on the individual baseline level of ROS, we immediately transferred 10 μl of heparinized whole blood into a silicon antireflective tube (Lumivial, EG & G Berthold, Germany). We added 90 μl of 10−4 mol l−1 luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydrophthalazine-1,4-dione; VWR International, Stockholm, Sweden) which was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO; VWR International, Stockholm, Sweden) and diluted with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4). 10 μl of PBS were added and the tube was shaken gently for mixing. The lumigenic substrate, Luminol, produces chemiluminescence when combined with an oxidizing agent, producing a low-intensity light reaction [40]. To measure full blood chemiluminescence produced in response to a secondary challenge (the first challenge was the stress reaction in vivo), a second tube was prepared in parallel as described above but 10 μl of 10−5 mol l−1 phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA; VWR International, Stockholm, Sweden) was added instead of 10 μl PBS [30]. The higher the extent of the first challenge (i.e., the stress reaction of the animal), the lower the chemiluminescence response to the artificial secondary challenge is going to be. In other words, low LCC values indicate high stress levels and vice versa.

Blood chemiluminescence for each tube was assessed every 5 min for a total of 30 s over a period of 30 min and expressed in relative light units (RLU), using a portable high sensitivity chemiluminometer (Junior LB 9509, EG & G Berthold, Germany). All measurements were carried out in the field inside a car, ensuring stable conditions above 15 °C and were performed immediately after the blood sample was collected. When not in the chemiluminometer, tubes were incubated at 37 °C in a lightproof water bath. The texture and adhesiveness of the cell microenvironment is essential for the in vivo determination of cell reactivity [41]. Using the LCC technique, working with minimal diluted whole blood without further manipulation of the cell and immediate performance of the analysis, ensures the structural integrity and morphology of the cell.

Statistical analysis

All statistical analyses were performed in R.3.0.2 [42]. To analyze whether the LCC was reflecting individual stress levels, we tested whether the LCC-peak (see Fig. 1) as well as the integral of the LCC curve (area under the curve, auc; Fig. 1) were affected by the time the animal spent in the trap with human presence at the capture site prior to handling (waiting time), the animal’s handling score and, its release score. Given that these two behavioral scores might represent proxies for an animal’s coping style [43] which in turn could affect its response to a stressor we also included the pairwise interactions of waiting time with the behavioral scores in the two negative binomial models (R-package “MASS” [44]), which were additionally corrected for the total number of neutrophils (both models n = 24).

Leukocyte Coping Capacity (LCC) curve (measured every 5 min for 30 s over 30 min) for European roe deer (n = 28), captured in box traps. The lower line represents basal levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) whereas the upper line represents PMA stimulated samples. The grey shaded area indicates the integral of the area under the curve (auc). Data points represent mean LCC levels (in relative light units), with error bars showing the standard error of the mean (S.E.M) for each time point

Preliminary analyses showed that including sampling period as a random effect in the models for correction did not affect the results and thus our conclusions. Given the small sample sizes we used the more parsimonious model and removed this parameter from the analysis beforehand. This also holds for all models presented below.

In order to test whether the stress reaction caused by human presence at the trap is also reflected by commonly used stress indicators, we tested whether heart rate, body temperature, total cortisol, N:L ratio or lactate levels were affected by waiting time, the animal’s handling score, its release score, or the pairwise interactions of waiting time with these two behavioral scores. For this purpose we performed two negative binomial models, on cortisol (n = 26) and N:L ratio (n = 24), and three linear models (R-package “stats” [45]), on heart rate (n = 27), body temperature (n = 27), and lactate levels (n = 19).

For all models, we determined relevant explanatory variables by comparing all nested models in a model selection table based on Akaike’s Information Criterion corrected for small sample size (AICc; [46, 47]) from which we selected the model with the lowest AICc. Model selection tables, including all models with a ΔAICc <4 and the Null-model only containing the intercept, are shown in the Additional file 3: Tables S3-S9. Full models of all linear models showed no evidence for serious deviations from normality according to the inspection of the distribution of residuals by means of histograms and quantile-quantile plots.

Finally, we tested pairwise correlations between all investigated stress indicators (all explanatory variables described above plus the two behavioral indices) using Pearson correlation tests. In order to correct for multiple testing we corrected the p-values using the Benjamini-Hochberg method [48]. However, as most p-values leveled off at around 1.0 after correction and were therefore not informative, we additionally report the uncorrected p-values in the results (Table 2).

Results

No mortalities or injuries occurred during captures or handling. Total handling time ranged from 7 to 29 min with a mean handling time of 14 (± standard deviation (SD)) 6.8 min. Mean values for complete blood counts and biochemistry parameters were within the reference ranges for European roe deer [49] (for details see Additional file 1: Tables S1 and Additional file 2: Table S2).

The animals had a mean heart rate (± SD) of 107 (±26) beats per minute and a mean body temperature (± SD) of 38.8 (±0.7) °C. The LCC-peaks occurred at 10 min in 78.5% of the roe deer, with exceptions at 5 (11%), 15 (7%), and 20 min (3.5%) (Fig. 1).

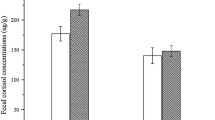

Besides the number of neutrophils, which was included for correction, the best models for the LCC-peak and the LCC-auc contained only the negative effect of waiting time (peak: estimate ± se = −0.046 ± 0.017, ΔAICc = 2.35, n = 24, Fig. 2a, Additional file 3: Table S3; auc: estimate ± se = −0.046 ± 0.014, ΔAICc = 2.69, n = 24, Fig. 2b, Additional file 3: Table S4).

Leukocyte Coping Capacity (LCC) -peak levels (a; n = 24) and LCC-auc (b; n = 24) expressed in relative light units (RLU) for European roe deer, captured in box traps, as function of the time the handling team was already present at the capture site prior to the handling procedure. With the increasing time of human presence prior to handling, the LCC response (peak as well as area under the curve, auc) is decreasing, indicating a significant increase of stress in the animals

The best models for cortisol included waiting time, release score and the interaction of the two (estimate ± se = 0.052 ± 0.021, n = 26, Additional file 3: Table S5). The best model on heart rate and lactate levels contained the handling score (estimate ± se = 8.719 ± 4.382, n = 27, Additional file 3: Table S6; slope ± se = 1.386 ± 0.803, n = 19, Additional file 3: Table S9). However, for those three parameters (cortisol, heart rate and lactate) the Null-model only containing the intercept was very close to those best models (cortisol: ΔAICc = 3.82, heart rate: ΔAICc = 1.42, lactate: ΔAICc = 0.22).

The best models on the N:L ratio as well as on body temperature were the Null-models only containing the intercept (N:L ratio: Additional file 3: Table S7; n = 24; body temperature: n = 27, Additional file 3: Table S8). The second best models contained the waiting time (estimate ± se = −0.047 ± 0.042) and the handling score (slope ± se = −0.124 ± 0.126), respectively.

In the pairwise comparisons between the different stress parameters, only LCC-peak and LCC-auc were significantly correlated (Table 2).

Discussion

The use of LCC to quantify stress in roe deer

Our results support our predictions that the LCC-technique is a suitable technique to quantify short-term stress levels as a result of capture and a short period of subsequent handling in non-anesthetized roe deer (prediction i). In contrast the traditional indicators of stress were not as conclusive (prediction ii). This study presents the first results of LCC for a ruminant species (Fig. 1). Although the exact capture time of the roe deer in this study was unknown and individuals consequently might have spent different timespans within the trap, causing some potential noise, our results clearly demonstrate that LCC reflects the duration of human presences at the capture site.

The obtained LCC responses match indications from previous studies on Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) [50], European badger (Meles meles) [31], Rhesus macaque (Macaca Mulatta) [51], European water vole (Arvicola terrestris) [7], water voles (Arvicola terrestris) [52], as well as on humans [33, 53, 54]. Interestingly, estimates of roe deer neutrophil production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) due to secondary challenge peak mostly after five (11%) or 10 min (78.5% of all animals). This finding indicates a considerably faster reactivity of roe deer neutrophils to external stimuli, such as bacterial peptides [55], as well as to stress induced changes in the blood stream [56]. Other species investigated so far reached LCC peak performance only at 15 min (e.g. European badger [31], Brown bear (Ursus arctos) [32]). This finding could potentially be explained by the fact that roe deer are prey animals [57, 58] and need to adjust their physiology rapidly in response to a threat by a predator. However, to elucidate the underlying mechanisms, further research is necessary.

Koolhaas et al. [12] highlighted that the term stress should be restricted to conditions which are uncontrollable and unpredictable and as a consequence are potentially life threatening. For prey animals like roe deer, being trapped and unable to escape the presence of a human being, a potential predator, undoubtedly reflects a situation meeting the described conditions and is expected to result in acute psychological stress [59]. Although we do not know the total time the animals spent in the box trap, which could constitute a potential bias in the animals stress response and LCC [60, 61], this stress is conclusively reflected in our LCC measurements. We found that LCC in roe deer significantly decreases with increasing time of humans being present at the capture site (i.e., waiting time; Fig. 2a, b). Correspondingly this confirms the fast change of this immune parameter in consequence of short-term stress. This is supported by findings of Ellard et al. [62] showing that already short-term mental stress causes a significant increase of activated leukocytes in humans, altering their oxidative capacity. Directly related to these findings, Shelton-Rayner et al. [33, 63] showed that acute psychological stress is decreasing LCC values in humans. Thus, our results endorse our first prediction that a stress reaction is already triggered by the presence of humans and not merely by the actual handling procedure.

Two individuals showed extremes in LCC peak values and the LCC-auc response respectively (Fig. 2a, b). Neutrophil ROS production is highly upregulated (>200%) by neutrophil “priming” agents such as chemoattractants (bacterial peptides/proteins), inflammatory cytokines (e.g. tumor necrosis factor alpha) or Toll-like receptor agonists (e.g. endotoxins) [64]. Bacterial infections and/or inflammatory processes increase chemoattractant levels in the blood stream and therefore increase neutrophil ROS production. This could potentially explain the high magnitude in LCC in these two individuals. The extreme nature of the priming effects facilitates a clear distinction to apparently healthy individuals (Fig. 2a, b). Removing these two outliers from the statistical analysis did not change our results.

Classical stress parameters

The more commonly and more frequently used measures of stress including heart rate [65, 66], body temperature [67], cortisol [19] and leukocyte profiles in terms of the N:L ratio [61, 68] as well as the two behavioral scores neither correlated with LCC values nor with each other and did not reflect our defined stressor. We attribute this lack of correlation to a large individual variation in how animals cope with a stressful situation behaviorally and physiologically [15, 69, 70], impeding the detection of quantitative effects of a stressor, at least at low sample sizes like they are commonly faced in field studies. Moreover, our results are supported by the findings of Esteruelas et al. [32] showing that LCC levels did not correlate with heart rate, N:L ratio nor cortisol concentrations in Scandinavian brown bears. It should be noted, however, that those animals were anesthetized, resulting in additional physiological alterations. As in our findings, the classical parameters measured by Esteruelas et al. [32] indicated that animals were certainly stressed, but likewise did not allow for quantifying stress responses [61]. This, however, is apparently not the case for the LCC. In the case of heart rate and body temperature it may be that these two parameters reflect the very immediate response of the organism to a stressor and that they are therefore not as conclusive towards events occurring several minutes prior to measurement.

Alternatively, this discrepancy between LCC and classical stress parameters could be explained by the characteristic of neutrophils to detect several biochemical alterations in the blood stream linked to stress. Neutrophils provide over 150 different receptors all of which are sensitive to signals of stress in the organism: endocrine factors in the plasma, changes in blood biochemistry and red cell hemodynamics, cytokines as well as changes of products released by the hypothalamic – pituitary – adrenal axis as well as the sympathetic nervous system [71]. Therefore the LCC response may be the cumulative result of the nearly simultaneous shift of all these factors, not allowing a clear correlation with one of the classical stress parameters, especially with low sample sizes.

Conclusions

Based on our findings, we strongly recommend minimizing both the time the handling teams spend next to restrained (trapped) animals and the handling time to an absolute minimum. This will improve animal welfare and minimize negative effects of stress induced physiological changes on the data collected. The LCC technique proved to be an excellent tool to quantitatively assess short term stressors, even with low sample sizes. The method allows for measuring the stress response in the context of trapped animals and human presence in a quantitative manner. In contrast, this was not possible with the classical stress parameters used in this study.

Due to the rapid changes in LCC in response to short-term stressors, we suggest to additionally analyze catecholamine levels, which could provide an important link between classical stress parameters and the immunological tool of LCC.

Abbreviations

- AICc:

-

Akaike’s Information Criterion corrected for small sample size

- auc:

-

area under the curve

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- GWRA:

-

Grimsö Wildlife Research Area

- HPA:

-

Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis

- LCC:

-

Leukocyte Coping Capacity

- N:L ratio:

-

Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- PMA:

-

Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- RLU:

-

Relative Light Units

- ROS:

-

Reactive oxygen species

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- S.E.M.:

-

Standard error of the mean

- SNS:

-

Sympathetic nervous system

References

Maublanc M-L, Bideau E, Launay C, Monthuir B, Gerard J-F. Indicators of ecological change (IEC) as efficient tools for managing roe deer populations: a case study. Eur J Wildl Res. 2016;62:189–97.

Carlson RI, Cattet MRL, Sarauer BL, Nielsen SE, Boulanger J, Stenhouse GB, Janz DM. Development and application of an antibody-based protein microarray to assess physiological stress in grizzly bears (Ursus arctos). Conserv Physiol. 2016;4:cow001.

Lynn SE, Porter AJ. Trapping initiates stress response in breeding and non-breeding house sparrows Passer domesticus: implications for using unmonitored traps in field studies. J Avian Biol. 2008;39:87–94.

Wikelski M, Cooke SJ. Conservation physiology. Trends Ecol Evol. 2006;21:39–46.

Broom DM. Animal welfare: concepts and measurement. J Anim Sci. 1991;69:4167–75.

McLaren G, Bonacic C, Rowan A. Animal welfare and conservation: measuring stress in the wild. In: Macdonald D, Service K, editors. Key topics in conservation biology; 2007. p. 120–33.

Moorhouse TP, Gelling M, McLaren GW, Mian R, Macdonald DW. Physiological consequences of captive conditions in water voles (Arvicola terrestris). J Zool. 2007;271:19–26.

Castle K, Gillin C, Hernandez S, Justice-Allen A, Lamberski N, Nichols M, Wolff P. Supplement editorial board: preface to and acknowledgments for the Journal of Wildlife Diseases special supplement: advances and improvements in wildlife welfare. J Wildl Dis. 2016;52:S1–3.

Romero LM, Wingfield JC. Tempests, predators, poxes, and people. Stress in wild animals and how they cope. New York: Oxford University Press; 2016.

Sapolsky RM, Romero LM, Munck AU. How do Glucocorticoids influence stress responses? Integrating permissive, suppressive, stimulatory, and preparative actions. Endocr Rev. 2000;21:55–89.

Koolhaas JM, Korte SM, De Boer SF, Van Der Vegt BJ, Van Reenen CG, Hopster H, De Jong IC, Ruis MAW, Blockhuis HJ. Coping styles in animals: current status in behavior and stress-physiology. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:925–35.

Koolhaas JM, Bartolomucci A, Buwalda B, de Boer SF, Flugge G, Korte SM, Meerlo P, Murison R, Olivier B, Palanza P, et al. Stress revisited: a critical evaluation of the stress concept. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2011;35:1291–301.

Nelson RJ, Demas GE, Klein SL, Kriegsfeld LJ. Seasonal patterns of stress, immune function, and disease. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2002.

Barrio IC, Hik DS, Bueno CG, Cahill JF. Extending the stress-gradient hypothesis - is competition among animals less common in harsh environments? Oikos. 2013;122:516–23.

Romero LM, Platts SH, Schoech SJ, Wada H, Crespi E, Martin LB, Buck CL. Understanding stress in the healthy animal – potential paths for progress. Stress. 2015;15:491–7.

Dantzer B, Fletcher QE, Boonstra R, Sheriff MJ. Measures of physiological stress: a transparent or opaque window into the status, management and conservation of species? Conserv Physiol. 2014;2:cou023.

Möstl E, Palme R. Hormones as indicators of stress. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2002;23:67–74.

Monaghan P, Metcalfe NB, Torres R. Oxidative stress as a mediator of life history trade-offs: mechanisms, measurements and interpretation. Ecol Lett. 2009;12:75–92.

Sheriff MJ, Dantzer B, Delehanty B, Palme R, Boonstra R. Measuring stress in wildlife: techniques for quantifying glucocorticoids. Oecologia. 2011;166:869–87.

Busch DS, Hayward LS. Stress in a conservation context: a discussion of glucocorticoid actions and how levels change with conservation-relevant variables. Biol Conserv. 2009;142:2844–53.

Delehanty B, Hossain S, Jen CC, Crawshaw GJ, Boonstra R. Measurement of free glucocorticoids: quantifying corticosteroid-binding globulin binding affinity and its variation within and among mammalian species. Conserv Physiol. 2015;3:cov020.

Wingfield JC, Kitaysky AS. Endocrine responses to unpredictable environmental events: stress or anti-stress hormones? Integr Comp Biol. 2002;42:600–9.

Otovic P, Hutchinson E. Limits to using HPA Axis activity as an indication of animal welfare. ALTEX. 2015;32:41–50.

Cabanac M, Aizawa S. Fever and tachycardia in a bird (Gallus domesticus) after simple handling. Physiol Behav. 2000;69:541–5.

Cabanac AJ, Guillemette M. Temperature and heart rate as stress indicators of handled common eider. Physiol Behav. 2001;74:475–9.

Tarlow EM, Blumstein DT. Evaluating methods to quantify anthropogenic stressors on wild animals. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 2007;102:429–51.

Rushen J. Some issues in the interpretation of Behavioural responses to stress. In: Moberg G, Mench J, editors. The biology of animal stress basic principles and implications for animal welfare. Wallingford: CAB International; 2000. p. 23–42.

Råberg L, Grahn M, Hasselquist D, Svensson E. On the adaptive significance of stress-induced immunosuppression. Proc R Soc B. 1998;265:1637–41.

Dhabhar FS. Effects of stress on immune function: the good, the bad, and the beautiful. Immunol Res. 2014;58:193–210.

Strobel S, Becker NI, Encarnação JA. No short-term effect of handling and capture stress on immune responses of bats assessed by bacterial killing assay. Mamm Biol. 2015;80:312–5.

McLaren GW, Macdonald DW, Georgiou C, Mathews F, Newman C, Mian R. Leukocyte coping capacity: a novel technique for measuring the stress response in vertebrates. Exp Physiol. 2003;88:541–6.

Esteruelas NF, Huber N, Evans AL, Zedrosser A, Cattet M, Palomares F, Angel M, Swenson JE, Arnemo JM. Leukocyte coping capacity as a tool to assess capture- and handling-induced stress in scandinavian brown bears (Ursus arctos). J Wildl Dis. 2016;52:S40–53.

Shelton-Rayner GK, Mian R, Chandler S, Robertson D, Macdonald DW. Leukocyte responsiveness, a quantitative assay for subjective mental workload. Int J Ind Ergon. 2012;42:25–33.

Cederlund G, Bergqvist J, Kjellander P, Gill R, Gaillard JM, Boisaubert B, Ballon P, Duncan P. Managing roe deer and their impact on the environment: maximising the net benefits to society. In: Andersen R, Duncan P, JDC L, editors. The European roe deer: the biology of success. Oslo: Scandinavian University Press; 1998. p. 337–72.

Kjellander P, Nordström J. Cyclic voles, prey switching in red fox, and roe deer dynamics - a test of the alternative prey hypothesis. Oikos. 2003;101:338–44.

Plard F, Gaillard JM, Bonenfant C, Hewison AJM, Delorme D, Cargnelutti B, Kjellander P, Nilsen E, Coulson T. Parturition date for a given female is consistently highly repeatable in five roe deer populations. Biol Lett. 2013;9(1):20120841.

Johansson A. Territory establishment and antler cycle in male roe deer. Ethology. 1996;102(4):549–59.

Arnemo JM, Ahlqvist P, Andersen R, Berntsen F, Ericsson G, Odden J, Brunberg S, Segerström P, Swenson JE. Risk of capture-related mortality in large free-ranging mammals: experiences from Scandinavia. Wildl Biol. 2006;12:109–13.

Montané J, Marco I, Manteca X, López J, Lavín S. Delayed acute capture Myopathy in three roe deer. J Vet Med A. 2002;49:93–8.

Merényi G, Lind J, Eriksen TE. Luminol Chemiluminescence: chemistry, excitation, emitter. J Biolumin Chemilumin. 1990;5:53–6.

Théry M, Jiménez-Dalmaroni A, Racine V, Bornens M, Jülicher F. Experimental and theoretical study of mitotic spindle orientation. Nature. 2007;447:493–U6.

R Core Team: R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2.15.0; 2013. [ http://www.r-project.org ].

Monestier C, Gilot-Fromont E, Morellet N, Debeffe L, Cebe N, Merlet J, Picot D, Rames JL, Hewison AJM, Verheyden H. Individual variation in an acute stress response reflects divergent coping strategies in a large herbivore. Behav Process. 2016;132:22–8.

Venables WN, Ripley BD. Modern Applied statistics with S. 4th ed. New York: Springer; 2002.

R Core Team: R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2015. [ http://www.r-project.org ].

Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrov BN, Csádki F, editors. Proceedings of the 2nd International symposium on information theory; Tsahkadsor, Armenia, USSR. Budapest: Akademiai Kiado; 1973. p. 267–81.

Hurvich CM, Tsai C-L. Regression and time series model selection in small samples. Biometrika. 1989;76:297–307.

Benjamini Y, Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. J R Stat Soc Ser B Methodol. 1995;57:289–300.

Küker S, Huber N, Evans A, Kjellander P, Bergvall UA, Jones KL, Arnemo JM. Hematology, serum chemistry, and serum protein electrophoresis ranges for free-ranging roe deer (Capreolus capreolus) in Sweden. J Wildl Dis. 2015;51:269–73.

Thompson I, White A, Fletcher TC, Houlihan DF, Secombes CJ. The effect of stress on the immune response of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.) fed diets containing different amounts of vitamin C. Aquaculture. 1993;114:1–18.

Honess PE, Marin C, Brown AP, Wolfensohn SE. Assessment of stress in non-human primates: application of the neutrophil activation test. Anim Welf. 2005;14:291–5.

Gelling M, Montes I, Moorhouse TP, Macdonald DW. Captive housing during water vole (Arvicola terrestris) reintroduction: does short-term social stress impact on animal welfare? PLoS One. 2010;5:e9791.

Huber K, Krötz-Fahning M, Hock B. Respiratory burst as a biomarker for stress responses. Protoplasma. 2006;229:221–4.

Shelton-Rayner GK, Macdonald DW, Chandler S, Robertson D, Mian R. Leukocyte reactivity as an objective means of quantifying mental loading during ergonomic evaluation. Cell Immunol. 2010;263:22–30.

Dahlgren C, Karlsson A. Respiratory burst in human neutrophils. J Immunol Methods. 1999;232:3–14.

Elbim C, Bailly S, Chollet-Martin S, Hakim J, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA. Differential priming effects of Proinflammatory cytokines on human Neutrophil oxidative burst in response to bacterial N-Formyl peptides. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2195–201.

Jobin A, Molinari P, Breitenmoser U. Prey spectrum, prey preference and consumption rates of Eurasian lynx in the Swiss Jura Mountains. Acta Theriol. 2000;45:243–52.

Wikenros C, Sand H, Wabakken P, Liberg O, Pedersen HC. Wolf predation on moose and roe deer: chase distances and outcome of encounters. Acta Theriol. 2009;54:207–18.

Wingfield JC, Ramenofsky M. Hormones and the behavioral ecology of stress. In: PHM B, editor. Stress physiology in animals. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press; 1999. p. 1–51. Sheffield Biological Sciences.

Omsjoe EH, Stien A, Irvine J, Albon SD, Dahl E, Thoresen SI, Rustad E, Ropstad E. Evaluating capture stress and its effects on reproductive success in Svalbard reindeer. Can J Zool. 2009;87:73–85.

Johnstone CP, Reina RD, Lill A. Interpreting indices of physiological stress in free-living vertebrates. J Comp Physiol B. 2012;182:861–79.

Ellard DR, Castle PC, Mian R. The effect of a short-term mental stressor on neutrophil activation. Int J Psychophysiol. 2001;41:93–100.

Shelton-Rayner GK, Mian RB, Chandler S, Robertson D, Macdonald DW. Quantitative physiological assessment of stress via altered immune functioning following interaction with differing automotive Interface technologies. Int J Hum Comput Int. 2011;27:900–19.

El-Benna J, Hurtado-Nedelec M, Marzaioli V, Marie JC, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Dang PMC. Priming of the neutrophil respiratory burst: role in host defense and inflammation. Immunol Rev. 2016;273:180–93.

Montané J, Marco I, López-Olvera J, Manteca X, Lavín S. Transport stress in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus): effect of a short-acting antipsychotic. Anim Welf. 2002;11:405–17.

Montané J, Marco I, Lopez-Olvera J, Perpinan D, Manteca X, Lavin S. Effects of acepromazine on capture stress in roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). J Wildl Dis. 2003;39:375–86.

Long NC, Vander AJ, Kluger MJ. Stress-induced rise of body temperature in rats is the same in warm and cool environments. Physiol Behav. 1990;47:773–5.

Davis AK, Maney DL, Maerz JC. The use of leukocyte profiles to measure stress in vertebrates: a review for ecologists. Funct Ecol. 2008;22:760–72.

Cockrem JF. Individual variation in glucocorticoid stress responses in animals. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2013;181:45–58.

Koolhaas JM, de Boer SF, Buwalda B, van Reenen K. Individual variation in coping with stress: a multidimensional approach of ultimate and proximate mechanisms. Brain Behav Evol. 2007;70:218–26.

Mian R, McLaren G, Macedonald DW. “Of stress, mice and men: a radical approach to old problems” in stress and Health. In: Oxington KV, editor. Stress and Health: new research. New York: Nova Sience Publishers; 2005. p. 61–79.

Acknowledgements

L. Jäderberg, G. Sjöö, L. Höglund, K. Jones, A. R. Græsli and S. Grønmo for assistance with captures and sampling. The Grimsö Wildlife Research Station and Inland Norway University of Applied Sciences provided logistical, equipment and financial support.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (PK), Marie-Claire Cronstedts Stiftelse and the Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (UAB, PK) as well as the Swedish Research Council (UAB).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed within the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Authors’ contributions

PK, UAB, JMA, ALE and NH, initiated the study and designed the experiment. SK and NH contributed during fieldwork and data collection. Equipment was provided by JMA, UAB and PK. Data analysis and preparation of figures was done by SGV with contribution of NH. NH and SGV drafted the manuscript and contributed equally. PK, UAB, ALE and JMA critically revised the manuscript. All authors participated in revisions and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All captures as well as all handling methods were approved by the Ethical Committee on Animal Experiments, Uppsala, Sweden (C302/2012) in accordance with Swedish and European legislation.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Hematology for free-ranging, non-anesthetized European roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). (DOCX 34 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Serum chemistry for free-ranging, non-anesthetized European roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). (DOCX 40 kb)

Additional file 3: Tables S3-S9.

Model selection tables. (DOCX 63 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Huber, N., Vetter, S.G., Evans, A.L. et al. Quantifying capture stress in free ranging European roe deer (Capreolus capreolus). BMC Vet Res 13, 127 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1045-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-017-1045-0