Abstract

Background

The liver has a large regenerative capacity. Hepatocytes can replicate and regenerate a diseased liver. However, as is the case in severe liver diseases, this replication may become insufficient or exhausted and hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs) can be activated in an attempt to restore liver function. Due to their bi-potent differentiation capacity, these HPCs have great potential for regenerative approaches yet over-activation does pose potential health risks. Therefore the mechanisms leading to activation must be elucidated prior to safe implementation in the veterinary clinic. Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling have been implicated in the activation of HPCs in mouse models and in humans. Here we assessed the involvement in canine HPC activation. Gene-expression profiles were derived from laser microdissected HPC niches from lobular dissecting hepatitis (LDH) and normal liver tissue, with a focus on Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling. Immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent studies were combined to assess the role of the pathways in HPCs during LDH.

Results

Gene-expression confirmed higher expression of Wnt/β-catenin and Notch pathway components and target genes in activated HPC niches in diseased liver compared to quiescent HPC niches from normal liver. Immunofluorescence confirmed the activation of these pathways in the HPCs during disease. Immunohistochemistry showed proliferating HPCs during LDH, and double immunofluorescence showed downregulation of Wnt/β-catenin and Notch in differentiating HPCs. Vimentin, a mesenchymal marker, was expressed on a subset of undifferentiated HPCs.

Conclusions

Together these studies clearly revealed that both Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling pathways are enhanced in undifferentiated, proliferating and potentially migrating HPCs during severe progressive canine liver disease (LDH).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Liver diseases occur frequently in the canine pet population. Around 12% of the dogs in first opinion practices have liver disease [1],[2] and account for 1-2% of a university veterinary clinical population [3]. It is conceivable that these numbers, based on the Cambridge region (UK) and the Utrecht University Clinics (the Netherlands), respectively, are exemplary for the West-European dog pet population. One third of chronic hepatitis cases are caused by copper accumulation. In addition, microorganisms, toxins and drugs have been reported to cause hepatitis in dogs. In more than 60% of cases, however, hepatitis remains idiopathic [3],[4]. The recently discovered canine hepacivirus is unlikely to cause canine hepatitis [5]-[7].

Irrespective of the cause of hepatocyte damage, the liver can recover from such insults due to replication of fully differentiated hepatocytes [8]. In case this replication is exhausted or otherwise hampered, hepatic progenitor cells (HPCs) are reported to have the potential to take over regeneration. These stem cells are believed to be bi-potential and to have the capacity to differentiate into either hepatocytes or cholangiocytes, depending on cellular demand [9]. HPCs are located in the terminal branches of the biliary tree, called the Canal of Hering [10]. Several publications describe the cellular and molecular constituents of the canine or feline HPC niche [11]-[15]. The niche is not just an anatomical region in the liver, but it has a biological function as it provides the cell- and matrix derived signals to instruct the HPC’s cellular fate.

In order to safely use HPCs for liver regeneration in a clinical setting where hepatocyte replication is insufficient, detailed knowledge of crucial signalling cascades for HPC activation is essential. Two signalling pathways, Wnt/β-catenin and Notch, are involved in proliferation and differentiation of progenitor cells including HPCs in other mammals [16]-[20]. This prompted the present focus on these two transmembrane signalling pathways in the activation of HPCs in canine liver diseases. Since lobular dissecting hepatitis (LDH) was previously observed to contain the highest number of activated HPCs, the activated HPC niche from LDH was microdissected and molecular analyses were performed in comparison with quiescent HPC niches harboured adjacent to portal areas of normal canine liver [13].

These data show that both Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling are enhanced in activated HPC niches in dogs with LDH. The previous descriptions of the cellular constituents of the canine HPC niche and the current investigation on specific signalling cascades clearly show the similarities with other mammals, including human [12],[13]. It is therefore conceivable that results of clinical approaches in human medicine will be applicable and beneficial in veterinary health care.

Results

Gene-expression profiling of laser microdissected HPC niches indicate activation of Wnt and Notch pathways

Representative pictures of laser microdissected HPC niches in normal liver and lobular dissecting hepatitis (LDH) stained with Keratin(K)7 (marker of HPCs) are depicted in Figure 1A. Expression levels of the Wnt receptor FZD1 and the Wnt-induced transcription factor TCF3 were significantly higher in LDH cases compared to normal controls, as measured in LMD samples (Figure 1B). Of the various Notch-receptor proteins, only NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 expression levels were significantly higher in diseased material (Figure 1C). In line is the observation that only ligand JAG1 is upregulated, whereas JAG2 is not (Figure 1C). Based on these expression levels of ligand and receptors, it was anticipated that an activated Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling cascade would be present in activated HPC niches (Figure 1B,C). Importantly, the expression levels of classical target genes for Wnt/β-catenin, AXIN2, and Notch signalling, HEY1, were indeed elevated in LDH, confirming active downstream signalling (Figure 1B,C).

Gene expression of Wnt and Notch signalling components is enhanced in HPC niches during disease. Examples of cryosections (6 μm) of normal liver and lobular dissecting hepatitis immunostained for Keratin 7 (A), a marker of HPCs and cholangiocytes. The red lines indicate the quiescent HPC niche in the periportal area of normal tissue and the activated HPC niche throughout the parenchyma of diseased tissue (A). These areas were specifically selected by means of laser microdissection for RNA isolation and gene expression analysis. Relative gene-expression for components of Wnt (B), and Notch (C) signalling pathways show upregulation of these pathways in HPC niches during disease. FZD1, Frizzled 1; TCF3, transcription factor 3; AXIN2, axis inhibitor 2; JAG, jagged; HEY1, hairy/enhancer of split-related with YRPW motif; N.S., not significant; N/D, not detectable.

Immunofluorescence confirm activated Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling in HPC during disease

To specify the cellular origin of the upregulated gene expression levels, double immunofluorescence for β-catenin/K7 (Figure 2A) and Notch1/Notch Intra Cellular Domain (NICD)/K7 was performed (Figure 2B). This revealed that β-catenin and Notch1/NICD were strongly expressed in the cytoplasm and/or nucleus of the cells of the ductular reaction in LDH. Expression of β-catenin in hepatocytes and cholangiocytes was membranous, indicative for a low activation status of the Wnt/β-catenin signalling cascade. Similarly, Notch1/NICD was expressed in canalicular- and less pronounced in basolateral membranes in hepatocytes in normal tissues.

Wnt and Notch signalling are active in HPCs during disease. Example of immunofluorescent double staining on cryosections (15 μm) against β-catenin (green) and Keratin(K)7 (red), with ToPro3 (blue) nuclear counterstaining in normal and LDH liver tissue (A, size bar indicates 100 μm). In normal tissue, β-catenin is present in a membranous staining pattern on hepatocytes and bile duct cells. No nuclear β-catenin was seen. In LDH, β-catenin is clearly increased and overlay shows cytoplasmic and nuclear presence of β-catenin in K7 positive cells (yellow and bright blue). Example of immunofluorescent double staining on cryosections (15 μm) against Notch/Notch Intra Cellular Domain (Notch/NICD; green) and K7 (red), with ToPro3 (blue) nuclear counterstaining in normal and diseased (LDH) liver tissue (B, size bar indicates 100 μm). In normal tissue, a canalicular staining pattern on hepatocytes and bile duct cells was found, no nuclear staining was present.

Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling coincide with HPC proliferation and mesenchymal characteristics but are lost with differentiation

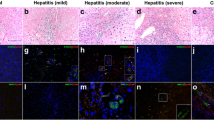

To investigate the functional involvement of Wnt and Notch in HPC activation, immunohistochemical and immunofluorescent stainings were performed (Figure 3). With Ki67 staining the proliferative activity in the tissues was assessed. In LDH, very few hepatocytes were found to be positive for Ki67, while a substantial number of Ki67 positive cells were found in the DR (Figure 3A). To evaluate the potential of HPCs to obtain mesenchymal characteristics, immunohistochemical staining for vimentin and double immunofluorescent staining for vimentin and PanCK was performed (Figure 3B,C). This revealed strong (co-)staining of vimentin in ductular structures, clearly showing expression of a mesenchymal marker on HPCs. To investigate the role of Wnt and Notch in HPC differentiation during liver disease, the mature hepatocyte marker HepPar1 in combination with β-catenin or Notch1/NICD in a double immunofluorescent staining was used. A clear polarisation of the ductular reaction was observed in such a way that the non-differentiated cells exhibited strong cytoplasmic and sometimes nuclear staining for both β-catenin and Notch1/NICD. This staining was lost in the intermediate and HepPar1 positive differentiated hepatocytes during continuation of the ductular reaction (Figure 3D,E). This is in line with the cytoplasmic and nuclear staining of β-catenin and Notch1/NICD in the K7-positive undifferentiated HPCs in Figure 2. In all staining procedures, negative controls remained negative, indicating the specificity of the antibodies used.

Proliferation and mesenchymal characteristics on HPCs and relation of differentiation with β-catenin and Notch1/NICD signalling. Immunohistochemical staining for Ki67 shows positive cells in the ductular reaction during LDH (A). Immunohistochemical staining for vimentin suggests positive ductular reactions (B) and an example of vimentin and PanCK double staining (C) shows clear co-localisation on HPCs in LDH. Double immunofluorescence against HepPar1 and β-catenin (D) or Notch1/Notch intracellular domain (Notch1/NICD; (E) in LDH shows polarisation of the ductular reaction: clear cytoplasmic staining of β-catenin or Notch/NICD is present in non-differentiated cells of the ductular reaction, and only membranous staining is present in differentiating and fully differentiated, HepPar1 positive, hepatocytes. Size bars indicate 50 μm.

Discussion

In the present study the involvement of the Wnt/β-catenin and Notch pathways was investigated in canine hepatic progenitor cell activation in LDH, a highly fibrotic and progressive liver disease. The combination of laser-microdissection, gene expression studies (Q-PCR) and immunofluorescence showed the enhanced signalling of the Wnt/β-catenin and Notch pathways in activated HPC niches compared to quiescent HPCs in normal liver. This extends the findings in mouse and human liver cancer and normal liver regeneration [19],[21]-[27]. The fact that this apparent activation was insufficient to restore the liver, dogs presenting with LDH die within a year after diagnosis [4], suggests that therapeutic opportunities are present here. The reason why HPCs fail to regenerate the liver seems to vary with the type of disease and may be due to insufficient proliferation, migration or differentiation [28]. New therapeutic strategies could address the pathways involved in these phases of activation.

The effect of Wnt/β-catenin was previously specified as (induction of) proliferation in rodent models of HPC activation [16],[24],[29],[30]. Similarly, a regulatory role for Notch in HPC proliferation is described [31],[32]. In LDH, the concurrent presence of active Wnt and Notch signalling and actively proliferating, Ki67 positive cells in the ductular reaction suggest a potential role for these pathways in proliferation of canine HPCs during disease as well. Another functional implication of Wnt and Notch signalling may relate to the acquisition of mesenchymal characteristics by HPCs. The presence of mesenchymal characteristics can relate to migratory potential, which is not equivalent to full epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), a disputed phenomenon in adult liver [33]-[35]. From a regenerative point of view, migration is necessary for HPCs to move toward the site of disease activity, and is likely to occur in concert with proliferation [36],[37]. Wnt and Notch pathways have been implicated in EMT and migratory potential of cells in different types of tissues and cancer development [38],[39]. In canine LDH vimentin positive HPCs also exhibit Wnt and Notch signalling, potentially indicating a causative relation in canine HPCs. It will be of interest to further functionally investigate this newly suggested role of Wnt or Notch in migration of HPCs during disease, as it may provide interesting potential for therapeutic intervention.

Besides the described role in proliferation and migration, both pathways can be involved in HPC differentiation. The influence of Wnt on cell fate determination is time and place dependent. During early embryonic development and in pluripotent embryonic stem cells in vitro Wnt activation leads to hepatic specification [40],[41]. Later in foetal liver development and in vitro in more committed multipotent cells, active Wnt inhibits (further) hepatocyte differentiation but rather guides cells to the biliary phenotype [42],[43]. Regarding the HPC as a committed progenitor cell, Wnt activation in LDH might stimulate bile duct differentiation and inhibit hepatocyte differentiation. An interesting finding in this study is that small hepatocytes lying in continuation with ductular cells, and possibly representing intermediate hepatocytes [44], display a membranous β-catenin staining pattern (Figure 3) similar to that of hepatocytes in normal tissue. This supports the theory that the Wnt/β-catenin pathway is no longer active during hepatocytic differentiation of ductular cells and is different from previous mouse data [21]. Unfortunately, the lack of specific markers for intermediate hepatocytes limits their description to size and localization only [11],[45]. The importance of Notch in liver development and hepatocyte differentiation is apparent in the mutation in the Notch ligand Jag1, which is associated with Alagille syndrome, presenting with aberrant bile duct development [25],[46]-[51]. More recently a distinctive role for the different Notch receptors has been explored, suggesting that Jag1-mediated Notch1 and Notch3 activation stimulates differentiation of hepatoblasts towards the biliary phenotype and inhibits hepatocytic differentiation. Vice-versa, Notch1 and Notch3 expression would be lost when (liver progenitor) cells differentiated towards hepatocytes [52],[53]. Converting these findings to the described results, it might be postulated that during LDH, where NOTCH1 and NOTCH3 expression is increased, HPC differentiation towards hepatocytes is inhibited, while bile duct differentiation may be enhanced. This is corroborated by the immunofluorescence stainings, where Notch1/NICD is lost with differentiation.

The activated states of the Wnt and Notch pathway in the diseased tissue were found at the same histological location, suggesting that Wnt and Notch act simultaneously. In view of this, the Wnt and Notch pathways may be intertwined in the activation of HPCs during liver disease, as occurs for example when cell-fate decisions are made during development [54]. Whether and how Wnt and Notch interact during HPC activation and in what manner this can be used for therapeutic benefit needs to be further investigated in molecular in vitro studies.

Conclusions

The combined Q-PCR and immunofluorescence results extend existing literature on other species and indicate a critical role for Wnt and Notch in proliferation, differentiation and/or migration of canine HPCs during rapidly progressing fibrotic liver disease with hampered hepatocytic proliferation. The descriptive data presented here suggest a role in HPC activation; in vitro experiments with canine hepatic progenitor cells, at present not available, could shed light on these questions separately. These data from a non-experimental liver disease in client-owned pets confirm the previous separate reports on Wnt and Notch signalling in rat and mouse injury models of liver disease [16],[23],[24],[29],[30],[50] and human data [19]. In the future, the implementation of pre-clinical experiments with Notch or Wnt inhibitors in order to enhance liver regeneration in patients could be mutually beneficial for dog and man.

Methods

Liver samples

Liver samples were obtained from privately owned dogs with LDH (n = 4; age range 1.5-2.5 years), a rapidly progressing disease characterized by diffuse inflammation, peri-cellular fibrosis and massive HPC activation [12],[13]. Informed consent was obtained as required under Dutch legislation. Liver pathology of the dogs was confirmed histologically by one board-certified veterinary pathologist according to the World Small Animal Veterinary Association (WSAVA)-standards [55]. Normal livers (n = 4; age range 1-3 years) were obtained from surplus animals of a non-liver related research project at the University Medical Centre Utrecht (University 3R policy).

Laser microdissection (LMD) of Keratin(K)7 positive cell patterns

Cryosections (10 μm) were cut using RNAse free blades on a cryostat at -20°C (Leica CM3050 cryostat, Leica Microsystems GmbH, Wetzlar, Germany), mounted on a pre-cooled (4°C) RNAse-free poly-ethylene naphthalene (PEN) membrane slide (P.A.L.M. MicroLaser Technologies AG, Burnried, Germany), immediately placed on dry ice and stored at -70°C for a maximum of one week until use. Rapid immunohistochemistry before laser microdissection (LMD) was performed with buffers and solutions prepared with DEPC-treated water (Ambion, Austin, TX). All glassware was treated with RNase Zap (Ambion) and washed with DEPC-treated water prior to use. To protect RNA from degradation during incubations at room temperature (RT), antibody and DAB solutions were prepared with 0.4 U/μl SUPERase RNase Inhibitor (Ambion). Frozen sections were taken from -70°C storage, immediately fixed in ice-cold acetone (-20°C) for 5 minutes and washed briefly (3-5 seconds) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Sections were incubated with K7 antibody (1:20; Dako, Glostrup, Denmark) in PBS for 7 minutes at RT, briefly washed in PBS and subsequently incubated in EnVision goat anti-mouse peroxidase-conjugated antibody (Dako) for 7 minutes at RT. Staining was visualised using the chromogen diaminobenzidine (DAB; Dako) for 3 minutes at RT. Finally, sections were dehydrated in an EtOH series (75-95-100%, 15 seconds each). The LMD procedure was performed within a maximum of 20 minutes upon staining with a Nikon eclipse TE300 inverted microscope (Nikon Inc. Instrument Group, Melville, NY) connected to a Sony 3-CCD Microscope ColorColour Video Camera (Sony Electronics Inc., Tokyo, Japan) using MMI CellTools software (MMI Molecular Machines & Industries AG, Glattbrugg, Switzerland). Tubes with an adhesive lid (MMI) were used to remove laser dissected cells from the whole liver tissue slide. After the LMD procedure, collected cells were retrieved with 50 μl Extraction Buffer (PicoPure RNA isolation kit, Molecular Devices, MDS Analytical Technologies, Sunnyvale, CA) and a short centrifugal step for further molecular processing. The cell-suspension was then incubated at 42°C for 30 min, centrifuged for 2 minutes at 800 × g, snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at -70°C until further use. From each sample, a total of 2-3.5 × 106 μm2 tissue was laser-dissected using four tissue sections per normal sample and two tissue sections per diseased sample.

RNA isolation and amplification

Total RNA was extracted from the LMD samples using the PicoPure RNA isolation kit (MDS Analytical Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and an on column DNAse treatment (0.1 U/μl) to remove all DNA contaminations (Qiagen, Benelux BV, Venlo, The Netherlands). RNA quality after LMD was determined using a RNA 6000 Pico-LabChip with an Agilent BioAnalyzer 2100 (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA). Amplification of the RNA was performed with the WT-Ovation™ Pico RNA Amplification System according to the manufacturer’s instructions (NuGEN Technologies Inc., Bemmel, The Netherlands). Making use of a DNA/RNA chimeric primer, cDNA was prepared from total RNA and amplified by linear isothermal DNA amplification. The product consists of single-strand DNA (ssDNA). The amplified product was purified with DNA Clean & Concentrator-25 from Zymo research according to the manufacturers instruction (Baseclear Lab Products, Leiden, The Netherlands), replacing Wash Buffer by fresh 80% ethanol.

Q-PCR analysis

For gene expression analysis, a SYBR Green based quantitative RT-PCR (Q-PCR) was performed on a Bio-Rad My-IQ detection system as described previously [56] for up to 45 cycles. Gene expression of described markers of HPCs and hepatocytes and of components of the Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling pathways was measured. Details of the primers and PCR conditions are listed in Table 1. Sequencing reactions confirmed amplification of the specific primer products in the Q-PCR reaction. Normalisation was secured due to the use of at least three independent reference genes: B2MG, HPRT, RPS5, and RPS19.

Statistical analysis

Relative gene expression of each gene-product (delta-Cq method) was used as the basis for all comparisons. The non-parametric Mann-Whitney U test was performed to assess statistical differences between normal and diseased tissue using SPSS software (SPSS Benelux, Gorinchem, the Netherlands). Gene expressions that were not detectable were arbitrarily set to Cq 45 for statistical analysis. p-Values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Immunohistochemistry/-fluorescence

Antibody details for immunohistochemistry/-fluorescence can be found in Table 2.

Whole liver cryosections (6 μm) were immunohistochemically stained for Ki67, a marker of active cell proliferation. Slides were air dried for 30 minutes at RT, fixed in ice-cold aceton:methanol 1:1 and washed in phosphate buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20 (PBS/T, pH 7.4). Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked for 30 minutes at RT in 0.3% H2O2 in PBS/T and background staining was blocked with 10% normal goat serum in PBS/T for 30 minutes at RT. Primary antibody was diluted in blocking serum and incubated for 60 minutes at RT. The HRP Envision system (Dako) was used. Staining was visualised using diaminobenzidine (DAB; Dako) and counter stained with haematoxylin quickstain (Vector Laboratories) for 5 minutes. Finally, slides were covered with Aquamount (Vector Laboratories). Canine duodenum served as the positive control (data not shown). Immunohistochemistry for vimentin was performed on 4 μm thick, paraffin embedded sections essentially as described previously [13]. Immunohistochemical pictures were obtained using an Olympus BX41TF Microscope (Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) with an Olympus U-CMAD3 camera and CellˆB software (AnalySIS, Olympus).

Immunofluorescent stainings were performed with parallel antibody incubations. The slides were incubated with mixed primary antibodies over night at 4°C and with mixed secondary antibodies at RT for 60 minutes. Rinsing steps were performed using TBS with 0.1% Tween 20 and slides were covered with Aquamount (Vector Laboratories). Immunofluorescent double stainings for K7/β-catenin and K7/Notch1-NICD were performed on 15 μm ice-cold acetone fixed (normal and LDH) liver-cryosections. Immunofluorescent double stainings against PanCK/Vimentin, HepPar/β-catenin and HepPar/Notch1-NICD were performed on 4 μm paraffin embedded canine LDH liver sections essentially as described previously [13]. For Notch1-NICD, incubation in 0.5% Triton for 20 minutes at RT was included for permeabilisation. The nucleus was stained with ToPro3 or DAPI. Slides were analysed using a Leica TCS SPE-II Confocal microscope and Leica software. In all procedures, negative controls were included constituting of a bilateral isotype control.

References

Center SA: Diseases of the gallbladder and biliary tree. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2009, 39 (3): 543-598. 10.1016/j.cvsm.2009.01.004.

Watson PJ, Roulois AJ, Scase TJ, Irvine R, Herrtage ME: Prevalence of hepatic lesions at post-mortem examination in dogs and association with pancreatitis. J Small Anim Pract. 2010, 51 (11): 566-572. 10.1111/j.1748-5827.2010.00996.x.

Poldervaart JH, Favier RP, Penning LC, van den Ingh TS, Rothuizen J: Primary hepatitis in dogs: a retrospective review (2002-2006). J Vet Intern Med. 2009, 23 (1): 72-80. 10.1111/j.1939-1676.2008.0215.x.

Favier RP: Idiopathic hepatitis and cirrhosis in dogs. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2009, 39 (3): 481-488. 10.1016/j.cvsm.2009.01.002.

Kapoor A, Simmonds P, Gerold G, Qaisar N, Jain K, Henriquez JA, Firth C, Hirschberg DL, Rice CM, Shields S, Lipkin WI: Characterization of a canine homolog of hepatitis C virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011, 108 (28): 11608-11613. 10.1073/pnas.1101794108.

Bexfield NH, Watson PJ, Heaney J, Heeney JL, Tiley L: Canine hepacivirus is not associated with chronic liver disease in dogs. J Viral Hepat. 2014, 21 (3): 223-228. 10.1111/jvh.12150.

van der Laan LJ, de Ruiter PE, van Gils IM, Fieten H, Spee B, Pan Q, Rothuizen J, Penning LC: Canine hepacivirus and idiopathic hepatitis in dogs from a Dutch cohort. J Viral Hepat. 2014, 21 (12): 894-896. 10.1111/jvh.12268.

Riehle KJ, Dan YY, Campbell JS, Fausto N: New concepts in liver regeneration. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011, 26 (Suppl 1): 203-212. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2010.06539.x.

Duncan AW, Dorrell C, Grompe M: Stem cells and liver regeneration. Gastroenterology. 2009, 137 (2): 466-481. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.05.044.

Saxena R, Theise N: Canals of Hering: recent insights and current knowledge. Semin Liver Dis. 2004, 24: 43-48. 10.1055/s-2004-823100.

Ijzer J, Schotanus BA, Vander Borght S, Roskams TA, Kisjes R, Penning LC, Rothuizen J, van den Ingh TS: Characterisation of the hepatic progenitor cell compartment in normal liver and in hepatitis: an immunohistochemical comparison between dog and man. Vet J. 2010, 184 (3): 308-314. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2009.02.016.

Schotanus BA, van den Ingh TS, Penning LC, Rothuizen J, Roskams TA, Spee B: Cross-species immunohistochemical investigation of the activation of the liver progenitor cell niche in different types of liver disease. Liver Int. 2009, 29 (8): 1241-1252. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2009.02024.x.

Kruitwagen HS, Spee B, Viebahn CS, Venema HB, Penning LC, Grinwis GC, Favier RP, van den Ingh TS, Rothuizen J, Schotanus BA: The canine hepatic progenitor cell niche: molecular characterisation in health and disease. Vet J. 2014, 201 (3): 345-352. 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.05.024.

Ijzer J, Kisjes JR, Penning LC, Rothuizen J, van den Ingh TS: The progenitor cell compartment in the feline liver: an (immuno)histochemical investigation. Vet Pathol. 2009, 46 (4): 614-621. 10.1354/vp.07-VP-0097-I-FL.

Kruitwagen HS, Spee B, Schotanus BA: Hepatic progenitor cells in canine and feline medicine: potential for regenerative strategies. BMC Vet Res. 2014, 10 (1): 137-10.1186/1746-6148-10-137.

Hu M, Kurobe M, Jeong YJ, Fuerer C, Ghole S, Nusse R, Sylvester KG: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in murine hepatic transit amplifying progenitor cells. Gastroenterology. 2007, 133 (5): 1579-1591. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.08.036.

Itoh T, Kamiya Y, Okabe M, Tanaka M, Miyajima A: Inducible expression of Wnt genes during adult hepatic stem/progenitor cell response. FEBS Lett. 2009, 583 (4): 777-781. 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.01.022.

Bi Y, Huang J, He Y, Zhu GH, Su Y, He BC, Luo J, Wang Y, Kang Q, Luo Q, Chen L, Zuo GW, Jiang W, Liu B, Shi Q, Tang M, Zhang BQ, Weng Y, Huang A, Zhou L, Feng T, Luu HH, Haydon RC, He TC, Tang N: Wnt antagonist SFRP3 inhibits the differentiation of mouse hepatic progenitor cells. J Cell Biochem. 2009, 108 (1): 295-303. 10.1002/jcb.22254.

Spee B, Carpino G, Schotanus BA, Katoonizadeh A, Vander Borght S, Gaudio E, Roskams T: Characterisation of the liver progenitor cell niche in liver diseases: potential involvement of Wnt and Notch signalling. Gut. 2010, 59 (2): 247-257. 10.1136/gut.2009.188367.

Sparks EE, Perrien DS, Huppert KA, Peterson TE, Huppert SS: Defects in hepatic Notch signaling result in disruption of the communicating intrahepatic bile duct network in mice. Dis Model Mech. 2011, 4 (3): 359-367. 10.1242/dmm.005793.

Boulter L, Govaere O, Bird TG, Radulescu S, Ramachandran P, Pellicoro A, Ridgway RA, Seo SS, Spee B, Van Rooijen N, Sansom OJ, Iredale JP, Lowell S, Roskams T, Forbes SJ: Macrophage-derived Wnt opposes Notch signaling to specify hepatic progenitor cell fate in chronic liver disease. Nat Med. 2012, 18 (4): 572-579. 10.1038/nm.2667.

Thompson MD, Monga SP: WNT/beta-catenin signaling in liver health and disease. Hepatology. 2007, 45 (5): 1298-1305. 10.1002/hep.21651.

Flynn DM, Nijjar S, Hubscher SG, de Goyet JV, Kelly DA, Strain AJ, Crosby HA: The role of Notch receptor expression in bile duct development and disease. J Pathol. 2004, 204 (1): 55-64. 10.1002/path.1615.

Chiba T, Zheng YW, Kita K, Yokosuka O, Saisho H, Onodera M, Miyoshi H, Nakano M, Zen Y, Nakanuma Y, Nakauchi H, Iwama A, Taniguchi H: Enhanced self-renewal capability in hepatic stem/progenitor cells drives cancer initiation. Gastroenterology. 2007, 133 (3): 937-950. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.06.016.

Gramantieri L, Giovannini C, Lanzi A, Chieco P, Ravaioli M, Venturi A, Grazi GL, Bolondi L: Aberrant Notch3 and Notch4 expression in human hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2007, 27 (7): 997-1007. 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2007.01544.x.

Tan X, Yuan Y, Zeng G, Apte U, Thompson MD, Cieply B, Stolz DB, Michalopoulos GK, Kaestner KH, Monga SP: Beta-catenin deletion in hepatoblasts disrupts hepatic morphogenesis and survival during mouse development. Hepatology. 2008, 47 (5): 1667-1679. 10.1002/hep.22225.

Köhler C, Bell AW, Bowen WC, Monga SP, Fleig W, Michalopoulos GK: Expression of Notch-1 and its ligand Jagged-1 in rat liver during liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2004, 39 (4): 1056-1065. 10.1002/hep.20156.

Roskams T: Different types of liver progenitor cells and their niches. J Hepatol. 2006, 45 (1): 1-4. 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.002.

Apte U, Thompson MD, Cui S, Liu B, Cieply B, Monga SP: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling mediates oval cell response in rodents. Hepatology. 2008, 47 (1): 288-295. 10.1002/hep.21973.

Yang W, Yan HX, Chen L, Liu Q, He YQ, Yu LX, Zhang SH, Huang DD, Tang L, Kong XN, Chen C, Liu SQ, Wu MC, Wang HY: Wnt/beta-catenin signaling contributes to activation of normal and tumorigenic liver progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2008, 68 (11): 4287-4295. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6691.

Jeliazkova P, Jörs S, Lee M, Zimber-Strobl U, Ferrer J, Schmid RM, Siveke JT, Geisler F: Canonical Notch2 signaling determines biliary cell fates of embryonic hepatoblasts and adult hepatocytes independent of Hes1. Hepatology. 2013, 57 (6): 2469-2479. 10.1002/hep.26254.

Fiorotto R, Raizner A, Morell CM, Torsello B, Scirpo R, Fabris L, Spirli C, Strazzabosco M: Notch signaling regulates tubular morphogenesis during repair from biliary damage in mice. J Hepatol. 2013, 59 (1): 124-130. 10.1016/j.jhep.2013.02.025.

Scholten D, Osterreicher CH, Scholten A, Iwaisako K, Gu G, Brenner DA, Kisseleva T: Genetic labeling does not detect epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition of cholangiocytes in liver fibrosis in mice. Gastroenterology. 2010, 139: 987-998. 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.05.005.

Swiderska-Syn M, Suzuki A, Guy CD, Schwimmer JB, Abdelmalek MF, Lavine JE, Diehl AM: Hedgehog pathway and pediatric nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Hepatology. 2013, 57 (5): 1814-1825. 10.1002/hep.26230.

Syn WK, Jung Y, Omenetti A, Abdelmalek M, Guy CD, Yang L, Wang J, Witek RP, Fearing CM, Pereira TA, Teaberry V, Choi SS, Conde-Vancells J, Karaca GF, Diehl AM: Hedgehog-mediated epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and fibrogenic repair in nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Gastroenterology. 2009, 137: 1478-1488. 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.06.051.

Kalluri R, Weinberg RA: The basics of epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Clin Invest. 2009, 119 (6): 1420-148. 10.1172/JCI39104.

Lim J, Thiery JP: Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: insights from development. Development. 2012, 139 (19): 3471-3486. 10.1242/dev.071209.

Lee JM, Dedhar S, Kalluri R, Thompson EW: The epithelial-mesenchymal transition: new insights in signaling, development, and disease. J Cell Biol. 2006, 172 (7): 973-981. 10.1083/jcb.200601018.

Sansom OJ, Reed KR, Hayes AJ, Ireland H, Brinkmann H, Newton IP, Batlle E, Simon-Assmann P, Clevers H, Nathke IS, Clarke AR, Winton DJ: Loss of Apc in vivo immediately perturbs Wnt signaling, differentiation, and migration. Genes Dev. 2004, 18 (12): 1385-1390. 10.1101/gad.287404.

Ober EA, Verkade H, Field HA, Stainier DY: Mesodermal Wnt2b signalling positively regulates liver specification. Nature. 2006, 442 (7103): 688-691. 10.1038/nature04888.

Hay DC, Fletcher J, Payne C, Terrace JD, Gallagher RC, Snoeys J, Black JR, Wojtacha D, Samuel K, Hannoun Z, Pryde A, Filippi C, Currie IS, Forbes SJ, Ross JA, Newsome PN, Iredale JP: Stabilization of beta-catenin affects mouse embryonic liver growth and hepatoblast fate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008, 105 (34): 12301-12306. 10.1073/pnas.0806522105.

Decaens T, Godard C, de Reyniès A, Rickman DS, Tronche F, Couty JP, Perret C, Colnot S: Highly efficient differentiation of hESCs to functional hepatic endoderm requires ActivinA and Wnt3a signaling. Hepatology. 2008, 47 (1): 247-258. 10.1002/hep.21952.

Ishii K, Yoshida Y, Akechi Y, Sakabe T, Nishio R, Ikeda R, Terabayashi K, Matsumi Y, Gonda K, Okamoto H, Takubo K, Tajima F, Tsuchiya H, Hoshikawa Y, Kurimasa A, Umezawa A, Shiota G: Hepatic differentiation of human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells by tetracycline-regulated hepatocyte nuclear factor 3beta. Hepatology. 2008, 48 (2): 597-606. 10.1002/hep.22362.

Robrechts C, De Vos R, Van den Heuvel M, Van Cutsem E, Van Damme B, Desmet V, Roskams T: Primary liver tumour of intermediate (hepatocyte-bile duct cell) phenotype: a progenitor cell tumour?. Liver. 1998, 18 (4): 288-293. 10.1111/j.1600-0676.1998.tb00168.x.

Libbrecht L, Desmet V, Van Damme B, Roskams T: The immunohistochemical phenotype of dysplastic foci in human liver: correlation with putative progenitor cells. J Hepatol. 2000, 33 (1): 76-84. 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80162-2.

Alagille D, Estrada A, Hadchouel M, Gautier M, Odievre M, Dommerques JP: Syndromic paucity of interlobular bile ducts (Alagille syndrome or arteriohepatic dysplasia): review of 80 cases. J Pediatr. 1987, 110: 195-200. 10.1016/S0022-3476(87)80153-1.

Li L, Krantz ID, Deng Y, Genin A, Banta AB, Collins CC, Qi M, Traski BJ, Kuo WL, Cochran J, Costa T, Pierpont ME, Rand EB, Piccoli DA, Hood L, Spinner NB: Alagille syndrome is caused by mutations in human Jagged1, which encodes a ligand for Notch1. Nat Genet. 1997, 16: 243-251. 10.1038/ng0797-243.

Tanimizu N, Miyajima A: Notch signaling controls hepatoblast differentiation by altering the expression of liver-enriched transcription factors. J Cell Sci. 2004, 117: 3165-3174. 10.1242/jcs.01169.

Nijjar SS, Crosby HA, Wallace L, Hubscher SG, Strain AJ: Notch receptor expression in adult human liver: a possible role in bile duct formation and hepatic neovascularization. Hepatology. 2001, 34: 1184-1192. 10.1053/jhep.2001.29399.

Nijjar SS, Wallace L, Crosby HA, Hubscher SG, Strain AJ: Altered Notch ligand expression in human liver disease: further evidence for a role of the Notch signaling pathway in hepatic neovascularization and biliary ductular defects. Am J Pathol. 2002, 160: 1695-1703. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)61116-9.

McCright B, Lozier J, Gridley T: A mouse model of Alagille syndrome: Notch2 as a genetic modifier of Jag1 haploinsufficiency. Development. 2002, 129: 1075-1082.

Kodama Y, Hijikata M, Kageyama R, Shimotohno K, Chiba T: The role of notch signaling in the development of intrahepatic bile ducts. Gastroenterology. 2004, 127: 1775-1786. 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.09.004.

Kuver R, Savard CE, Lee SK, Haigh WG, Lee SP: Murine gallbladder epithelial cells can differentiate into hepatocyte-like cells in vitro. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007, 293: G944-G955. 10.1152/ajpgi.00263.2006.

Hayward P, Kalmar T, Arias AM: Wnt/Notch signalling and information processing during development. Development. 2008, 135: 411-424. 10.1242/dev.000505.

Van den Ingh TSGAM, Van Winkle T, Cullen JM, Charles JA, Desmet VJ: Morphological classification of parenchymal disorders of the canine and feline liver: 2. Hepatocellular death, hepatitis and cirrhosis. WSAVA Standards for Clinical and Histological Diagnosis of Canine and Feline Liver Disease. Edited by: Rothuizen J, Bunch SE, Charles JA. 2006, Saunders-Elsevier, Edinburgh, 85-102. 10.1016/B978-0-7020-2791-8.50011-3.

van Steenbeek FG, Van den Bossche L, Grinwis GC, Kummeling A, van Gils IH, Koeramp MJ, van Leenen D, Holstege FC, Penning LC, Rothuizen J, Leegwater PA, Spee B: Aberrant gene expression I dog with portosystemic shunts. PLoS One. 2013, 8: e57662-10.1371/journal.pone.0057662.

Acknowledgements

The assistance of Anko de Graaf (Centre of Cellular Imaging, Utrecht University, the Netherlands) is greatly appreciated. This work was sponsored by the Dutch Research Counsel NWO ZON/MW (grant-numbers 92003538 and 16004121).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BA conceived the study, carried out the experiments and wrote the manuscript. HK participated in the design of the study and helped write the manuscript. TI interpreted the stainings. JR and LP participated in the design of the study. BS conceived the study, participated in design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Schotanus, B.A., Kruitwagen, H.S., van den Ingh, T.S. et al. Enhanced Wnt/β-catenin and Notch signalling in the activated canine hepatic progenitor cell niche. BMC Vet Res 10, 309 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-014-0309-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12917-014-0309-1