Abstract

Background

Although missed appointments in healthcare have been an area of concern for policy, practice and research, the primary focus has been on reducing single ‘situational’ missed appointments to the benefit of services. Little attention has been paid to the causes and consequences of more ‘enduring’ multiple missed appointments in primary care and the role this has in producing health inequalities.

Methods

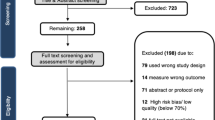

We conducted a realist review of the literature on multiple missed appointments to identify the causes of ‘missingness.’ We searched multiple databases, carried out iterative citation-tracking on key papers on the topic of missed appointments and identified papers through searches of grey literature. We synthesised evidence from 197 papers, drawing on the theoretical frameworks of candidacy and fundamental causation.

Results

Missingness is caused by an overlapping set of complex factors, including patients not identifying a need for an appointment or feeling it is ‘for them’; appointments as sites of poor communication, power imbalance and relational threat; patients being exposed to competing demands, priorities and urgencies; issues of travel and mobility; and an absence of choice or flexibility in when, where and with whom appointments take place.

Conclusions

Interventions to address missingness at policy and practice levels should be theoretically informed, tailored to patients experiencing missingness and their identified needs and barriers; be cognisant of causal domains at multiple levels and address as many as practical; and be designed to increase safety for those seeking care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Non-attendance at health appointments has garnered significant policy attention in high income countries, often framed in terms of waste, inefficiency, value-for money, long waiting lists or reduced capacity within services struggling to meet demand [1,2,3,4]. The existing evidence base around non-attendance has several strands. Some studies identify patient- or service-side variables associated with non-attendance, and increasingly their findings are used to build machine-learning algorithms to predict, and schedule around, non-attendance [5,6,7]. Other research uses surveys, questionnaires and interviews with staff and patients to build a picture of why appointments are missed. Intervention studies build upon these to test strategies for reducing non-attendance, typically measuring percentage reductions across the general patient population or among all patients missing appointments. These existing approaches rarely distinguish patients missing single appointments—potentially a situational issue—from patients who miss multiple appointments, for whom barriers to care may be more enduring. They also retain a primary focus on the impacts of non-attendance for health services rather than patients, with interventions oriented towards what provides those services with greatest benefit.

Multiple missed appointments have received occasional attention within this research base, with a variety of definitions. Some take absolute numbers: Traeger et al. [8] differentiate those missing 3 appointments (3.4% of patients) from those missing 5 or more (3.8%); Dumontier et al. [9] focusing on the 2% of patients who missed 6 or more appointments over 18 months; Cashman et al. [10] the 30% of patients missing 3 or more appointments over 18 months; or Chapman et al. [11] the patients missing 4 or more appointments over a 12-month period. Others look in relative terms, whether at missed appointments as a proportion of a patient’s total appointments—in Shimotsu et al. [12] 20% of patients miss more than 30% of their appointments, while 9% of patients miss more than one third of their follow-up appointments in Parker et al. [13]—or relative to other patients, as in Samuels et al. [14] who focus on patients above the 90% percentile in missed appointment rate. This paper follows a large-scale epidemiological project aimed at addressing knowledge gaps around multiple missed appointments in UK primary care. The project differed from many prior papers by directly linking multiple missed appointments to poor health outcomes, providing a clinical justification for a definition of missingness. After controlling for each patients’ total number of appointments, this project found that patients missing more than 2 general practice (GP) appointments per year on average over a 3-year period had multiple long-term physical and mental health conditions, experienced significant socioeconomic disadvantage, complex health needs, had poorer health outcomes and a significantly higher prevalence of premature mortality than patients who did not miss as many appointments [15,16,17,18,19]. This contributed to our current and less numerically stringent working definition of missingness as the repeated tendency not to take up offers of care, such that it has a negative impact on the person and their life chances [20]. We hypothesised that the causes of missingness are different in duration, complexity or intensity than those leading to single missed appointments. Interventions designed to tackle single missed appointments are likely be a poor fit for these patients and may increase access inequalities [21]. There is an urgent need to understand why missingness occurs, in order to intervene effectively and mitigate it and its negative impacts.

Methods

We carried out a realist review of evidence to help us understand the causal dynamics underpinning missingness [22]. Realist approaches aim to develop a theory about the underlying dynamics causing or sustaining a problem [23]. They seek to explain “demi-regularities” or “semi-predictable patterns of behaviour” by exploring the key mechanisms underpinning an outcome pattern and the contexts in which they are activated ([24], p.2). The goal is to produce a realist programme theory that contains Context-Mechanism-Outcome configurations (CMOCs) outlining the mechanisms that cause an outcome and the contexts in which those mechanisms are activated [25].Theory is developed interpretatively by gathering and synthesising evidence from a range of documentary sources. This occurs in five stages, summarised in Table 1 [21, 22, 24]. Our review was registered with PROSPERO (ID CRD42022346006), and the methods are explained fully in the protocol [20]. The review follows the Realist And MEta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) project standards for realist synthesis [25, 26]. The views expressed are the authors and not necessarily those of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) or the Department of Health and Social Care who funded the study via NIHR. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Overview of the evidence base

The findings below come from a total of 197 documents. The majority are from the UK (n = 110) or the USA (n = 37) and a significant proportion (n = 86) focus solely on primary care with others focused on other forms of healthcare provision. As such, while these findings are written with UK-based primary care in mind, they have a broader applicability across different service settings, geographical locations and health systems. A PRISMA diagram and description of included studies are included in Sects. 4 and 5 of Additional file 1. The most common study design explored statistical associations between patient/practice variables and missed appointments by exploring administrative data alone (n = 45), combined with questionnaires/surveys (n = 22) or with qualitative methods (n = 9). These studies vary substantially in their findings which may speak to unaddressed contextual heterogeneity or the use of different or contested variables—issue identified elsewhere in the literature [27, 29, 39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46]. They also provide limited explanatory insight or theoretical engagement [14, 39, 40, 47]. Survey and questionnaire studies (n = 27 alone, n = 29 mixed methods), designed to provide further causal insight, also contain issues of heterogeneity and definition, use pre-set, closed questions and present broad, prima facie reasons for non-attendance, and have been critiqued for obscuring complex causal realities [27, 48,49,50,51]. Studies report issues recruiting patients at risk of missing appointments, who may be less likely to participate in such research [42, 44, 52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Some designs actively exclude relevant patient groups—for example, those with existing mental health issues, cognitive impairments, learning disabilities or who do not speak English [46, 48, 60,61,62,63,64]. Other methods are indirectly exclusionary, such as reliance on single, monolingual postal surveys, which may disadvantage those with no fixed address or who have literacy or language needs [45, 65, 66]. Research, like healthcare, has a “missingness” problem to address [45, 66].

In exploring missingness, there is a risk of perpetuating problematic narratives embedded within the existing literature. Language of non-attendance or non-engagement and related concepts like “non-compliance” [67], “failure to attend” [50], “chaotic” [32, 35, 68, 69] and “hard to reach” [70], p.14) all speak to patient-side problems and create a foundation for studies (and thus findings) that focus attention solely on patients. Often specific subgroups of patients, including those missing multiple appointments, are framed as particularly problematic. This was discussed by our Stakeholder Advisory Group, who felt that many patients are not attended to by services, and by literature suggesting that services, not patients, are “hard to reach” [41, 48, 71]. Other definitional challenges included the lack of shared definition of missed appointments—some studies include short-notice cancellations or lateness, while others do not—and of a shared definition of missingness, making comparability or generalisability harder [8,9,10,11,12,13,14, 46, 49, 72]. Others question whether missingness even exists as a meaningful category for study [40, 73]. Sections 7.2 of Additional file 1 reflects further on the process of synthesising a narrative from this challenging evidence base.

Theoretical framework for the evidence synthesis

Despite these challenges, studies can still provide “evidential fragments” that can contribute to the programme theory through realist synthesis ([74], p135). The findings below are derived from this process, using fundamental causation theory and the candidacy framework to interpret the evidence [75,76,77,78]. Fundamental causation suggests that limited access to “flexible resources”—including knowledge, money, power, prestige and social connections—inhibits whether and how people pursue good health ([77], p.135). People’s “habitus”—unconscious or semi-conscious ways of knowing, being or acting, patterned by social position and which orient a person in the world—is also influential in health behaviours [75, 77]. A patient’s resources and habitus interact with the institutional processes of service-delivery to permit, enhance or block their health-promoting efforts [75, 77]. Candidacy similarly proposes that inequalities of service access/uptake occur in the interaction between the identities and resources of individuals seeking care (or not) and their (mis)alignment with structural and cultural qualities of services [78,79,80]. It outlines a series of domains: how patients come to identify themselves as candidates for a service; how they navigate to point-of-entry; how they align with service permeability/porosity—the cultures and structures governing access and use; how they present to services; how services respond with adjudications and offers which candidates, in turn, negotiate or resist [78]. This occurs within local operating conditions—the “localised cultural, organisational and political contexts” of services ([80], p.819). This approach supports a definition of non-attendance as the result of “a critical level of unsuitability in the agreed arrangements for an access episode” ([29], p.183)—an issue of the interaction between patients and healthcare providers. In missingness, this extends to an enduring unsuitability covering multiple access episodes. Our theoretical framework is explored further in Sect. 7.1 of Additional file 1, and the summary findings presented below are discussed in further detail in Sect. 7.3.

Results

Identification: is this “’for me?”

A patient’s decision of whether to attend is influenced by a range of beliefs and perceptions about themselves and their health and the perceived usefulness, importance or appropriateness of attending. Identification extends beyond the situational lens of the single appointment towards a wider identification around the service, unfolding over time. Ideas of ‘normal’ underpin a patient’s sense of acceptable or reasonable action (their habitus) and their sense of whether a service is ‘for me’ [40, 81]. Patients may not attend an appointment because they no longer see any need or purpose—symptoms may resolve or be mild, they may have few complications, minimal concern, feel their condition does not impact upon their everyday lives or is manageable without further input [14, 40, 42, 47, 56, 62, 64, 68, 82,83,84,85,86]. This may be particularly so in the context of long-term health conditions where many appointments are set by service providers, not requested by patients [13, 14, 27, 29, 37, 40, 46, 66, 82, 83, 86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95].

Conversely, some patients experience a high degree of worry or fear around their health or their appointments and may manage that through denial or avoidance [40, 46, 48, 62, 64, 96,97,98,99]. Many patients in adverse circumstances or with poor health have low expectations around what constitutes ‘normal’ health or may believe that healthcare can do nothing for them [8, 11, 48, 59, 62, 64, 66, 69, 96, 100, 101]. If past experiences of seeking care and support have not been beneficial, or provider and patient are “misaligned” ([11], p.4) in their understanding of the causes or solutions to health problems, or of the format or purpose of appointments, this might increase the sense that future attendance is of limited value [11, 50, 62, 64, 71, 83, 86, 93, 102, 103]. Identification may be influenced by the dynamics of specific conditions—mental health conditions, dementia, cognitive impairment—which influence how patients understand their health or need for healthcare [50, 87, 103]. Ideas of ‘normal’ exist within social relationships with peers, families or communities, moving the lens from ‘for me’ to for us’ [40, 46, 66, 81, 98, 103, 104]. Some candidacies may be suppressed by stigma, shame or embarrassment around health conditions; others by the belief that health services are unsuitable or inappropriate in cultural or community terms for the problems people experience [8, 48, 64, 99, 103, 105,106,107]. Crucially, these elements of identification can overlap or conflict or change over time—identities are neither static nor singular. The evidence synthesis underpinning this domain can be found in Sects. 7.3.1 and 7.3.2 of Additional file 1.

Relational candidacies

Patients’ past experiences of services play a significant role in their willingness to attend in future and can impact on the sense that services are “for me” in relational terms. Difficult experiences in past appointments or appointment-making might involve patients feeling unheard or unseen, their perspectives or experiences discounted [11, 14, 44, 62, 66, 69, 93, 102,103,104,105, 108,109,110,111]. Unaddressed interpersonal communication needs may contribute to this—including lack of interpreting, language inaccessibility or power imbalances contributing to anxieties, mistrust or low confidence, all of which inhibit the giving or receiving of information [44, 45, 57, 64, 71, 94, 96, 111,112,113]. These may contribute to misalignment and the risk of mismatch between a patients’ needs and circumstances (their candidacies) and the adjudications and offers of services [101, 105, 108, 114]. It also creates a problematic power dynamic where patients feel disempowered, disrespected and excluded from their own care.

Relational dynamics are refracted through wider life experiences and circumstances, and some may be particularly at risk of problematic relational or power dynamics and their impacts. Some patients may have experienced judgemental, punitive or stigmatising interactions with services, whether because of missed appointments or other aspects of their lives or identities [11, 31, 40, 68, 69, 96, 101, 103, 105, 111, 113,114,115]. Stigma is part of fundamental causation because it increases exposure to identity-threatening encounters while reducing interpersonal power, making people less likely to be acknowledged or heard within them [116]. The internalisation and anticipation of stigma or hostility is thus a central part of missingness, resulting in reactive avoidance to prevent relational threat or the threat to identity, even in circumstances of urgent need [46, 96, 104, 105, 111, 117]. Interpersonal encounters with unequal power dynamics may be particularly challenging for patients with difficult experiences of caring relationships and histories of psychological trauma, abuse, attachment issues, neglect or violence, contributing to approach-avoidance—where appointments have the potential to resolve health issues but are also the source of exposure to unmanageable anxiety and stress [8, 11, 33, 40, 45, 50, 71, 93, 108, 112]. The risk of mistrust is greater where systems do not support continuity of clinician, sufficient time within appointments or adequate communication support [11, 13, 14, 29, 32, 40, 42, 44, 46, 47, 51, 69, 82, 86, 90, 91, 93, 103, 105, 108, 118,119,120]. The evidence synthesis underpinning this domain can be found in Sects. 7.3.2 and 7.3.3 of Additional file 1.

Competing candidacies, multiple demands and limited resources

Patients experiencing missingness may be positioned in precarious socioeconomic circumstances that expose them to disruptive forces that threaten health, material and social wellbeing [9, 11, 17,18,19, 43, 49, 59, 62, 65, 71, 96, 103]. Ideas of competing demands or “conflicting candidacies”([79], p.56) shows how multiple urgent and competing priorities might result in reduced prioritisation of health or appointment attendance relative to other needs [30, 32, 36, 40, 50, 55, 57, 59, 62, 82, 83, 99, 102, 103, 107, 121,122,123,124,125,126,127,128]. By virtue of socioeconomic position, patients may have reduced access to the flexible resources to protect them against these forces, while experiencing multiple pressures on the personal, material and social resources they do have access to [77]. These demands include treatment burden and other appointments [4, 10, 11, 15, 17, 19, 28, 41, 43, 44, 48, 59, 61, 62, 64, 73, 83, 84, 86, 93, 100, 128,129,130,131,132,133,134,135]; employment responsibilities, employer inflexibility and the financial costs of missing work [11, 40, 44, 46,47,48,49, 59, 64, 81, 106, 107, 109, 115, 123, 135,136,137]; and caring responsibilities taking precedence [14, 40, 41, 44, 48, 59, 64, 99, 131, 138]. Patients experiencing severe and multiple disadvantages may have to prioritise accommodation, physical safety and survival demands over healthcare [43, 48, 53, 64, 65, 69, 71, 81, 96, 103, 114, 139]. Travelling to appointments requires resources that may be limited or needed to meet other demands [27, 28, 30,31,32, 36, 39, 40, 47, 55, 56, 83, 90, 125, 126, 140]. Disabilities or severe physical or mental health symptoms can make travelling to appointments unsafe or unmanageable [8, 9, 13, 15, 30,31,32, 36, 40, 41, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50, 54, 55, 58, 60,61,62, 64, 65, 68, 82, 84, 86, 89, 90, 96, 99, 100, 103, 105,106,107,108,109,110, 122, 125, 126, 128, 129, 133, 141,142,143,144,145,146,147,148,149,150]. Social connections and their resources may be beneficial but are not always available to help [11, 44, 45, 48, 49, 62, 63, 65, 101, 103, 112, 122, 126, 130, 134]. Evidence synthesis Sects. 7.3.4, 7.3.6, and 7.3.7 contribute to the findings in this domain.

Permeability and appointment-making

Primary care in the UK is a gatekeeper-led system, with a specific structure and certain cultural and behavioural expectations that must be met to navigate it successfully. Patients experiencing missingness may struggle with these aspects of permeability [78]. Registration and appointment systems in general have been described as a “threat” ([78], p.6) to some patients and a contributor to health inequalities [71, 101, 117]. By not attending in the past, patients are positioned as deviant or troublesome in the eyes of staff, creating “friction” ([115], p.642) and many of the relational challenges above [19, 35, 36, 40, 68, 69, 96, 115, 118, 137, 151]. Appointment-making requirements might be narrow and hard for patients to fulfil—calling at certain times, with telephone-only systems, to monolingual staff—and the personal resources (knowledge, skills, confidence, language) needed to fulfil these expectations or to negotiate and persist in pursuit of the right appointment are unequally distributed or depleted by negative experiences with services [18, 32, 47, 58, 69, 96, 105, 117, 137]. If services do not offer a timely appointment, patient circumstances change—they may forget, symptoms resolve, motivations change or other demands emerge, accounting for the almost universal finding that delays lead to missed appointments [18, 27,28,29,30,31,32, 39, 40, 51, 69, 90, 91, 96, 119, 152] [9,10,11, 18, 19, 27, 35, 37, 40, 46, 50, 51, 69, 82, 100, 101, 103, 109, 118, 122, 137, 138, 153, 154]. If services do not offer a convenient time, patients may not be able to reconcile attendance with competing demands or with the rhythms and patterns of their lives [9, 11, 29, 32, 37, 40,41,42, 46, 47, 49,50,51, 61, 66, 83, 87, 96, 100, 101, 106, 109, 111, 113,114,115, 123, 128, 131, 135, 155]. If the system does not permit or support patient choice in whom they see, in where or how they attend (in-person/virtually/at home/in practice), in communication support or in how much time is afforded to them, candidacies might be disrupted [18, 40, 44, 57, 59, 66, 101, 137, 148, 156, 157]. Errors, miscommunications or misunderstandings may be caused by service factors: failures to notify patients of appointments; providing incorrect details; booking appointments or notifying patients at short notice; using inaccessible or unsuitable forms of communication; and not providing ways for patients to easily amend or cancel their appointments [11, 29, 30, 36, 40, 41, 44,45,46,47, 54, 55, 57, 59, 61, 82, 86, 88,89,90, 115, 117, 122, 127, 128, 132,133,134,135, 142, 143, 145, 147, 158]. Sections 7.3.5, 7.3.7 and 7.3.3 of Additional file 1 provide the evidence synthesis for these findings.

The importance of local operating conditions

McLean et al. [40] suggest that non-attendance comes from service inaccessibility, inflexibility or unsuitability and recommend “diagnosing which of these pathologies is predominant in a particular setting” (p.101). Yet, research is often limited in reporting on the contextual conditions of service settings or the influence of specific local circumstances on findings. When reported, this information is often limited to patient demographics and numerical staffing data or brief description of some elements of service administration such as hours of operation, booking systems or any existing measures to reduce non-attendance. These are rarely then integrated into findings. Studies exploring administrative data across multiple settings can often make it appear as though missingness occurs in an institutional, political and economic vacuum.

The influence of local conditions can be inferred from the findings above—for example, in whether service staff hold stigmatising attitudes; whether staffing and appointment systems support timely or convenient access or relational continuity; in what additional services are offered within a practice, health centre or wider community. Less well-articulated are the wider structural influences on service delivery—staffing, resourcing and the wider political economy of healthcare. In response to recent UK government statements around non-attendance, the Royal College of General Practitioners points towards an existential crisis in primary care around workload, workforce and staff turnover impacting upon appointment availability and service quality [159,160,161]. Included studies suggest that these issues are likely to limit appointment availability (and thus convenience and flexibility), time spent with patients or the emotional resources of practitioners to participate in person-centred, trauma-informed care [40, 66, 101, 103, 162]. Models of funding that are based on numerical targets may actively discourage in-depth engagement with patients with more complex needs [66, 69, 71, 117]. Several papers discuss the benefits of specialist primary care provision for groups experiencing access issues, but these services often face insecure and limited funding and local variability and may risk ‘ghettoising’ primary care rather than seeking to improve it [69, 71, 101, 105, 111]. Candidacy issues in other areas of the health and social care system are also relevant. Issues of treatment burden connect to whether care is integrated or co-located or whether collaboration exists between services. If not, patients may fall into gaps, and many experience difficulties navigating referral thresholds and eligibility criteria, leaving them without adequate support and with reduced trust in the system to meet their needs [46, 62, 69, 71, 101, 103, 108, 111, 112, 163]. In the UK, these issues are exacerbated by austerity, with impacts on the resources available to local authorities, third sector organisations, and to many patients themselves. More recently, the cost of living crisis has impacted on the resources available for people to travel to appointments, and to access medications, and other essentials required to maintain or manage their health [140]. The absence of many of wider contextual issues from the existing research means that many causal influences remain unseen.

Discussion

These findings have several implications. There is a pressing need to move from framing missed appointments as an issue for services created by patients, towards perspectives exploring the interaction between patients’ circumstances and service dynamics [29, 40, 78]. Studies into non-attendance would benefit from including a ‘missingness’ perspective in their design—identifying missingness in administrative data, actively seeking the perspectives of those experiencing missingness using inclusive methods of recruitment and data collection and stratifying findings to report on missingness rather than just missed appointments. Positive examples in this review include those studies comparing findings around non-attendance, health outcomes and circumstances for those experiencing missingness with those who miss fewer or no appointments [15,16,17,18,19, 56, 58, 64, 93]. Reflections on the representativeness of samples (including non-respondents) would be beneficial for contextualising findings [55, 59, 95]. Further explication of local operating conditions would also support contextualisation of heterogeneous research findings [27, 46, 103]. Finally, we suggest that non-attendance research rebalance the disproportionate focus on statistical associations and surveys with in-depth research (e.g. qualitative or mixed-methods) and work underpinned by substantive theoretical engagement [14, 39, 40, 47]. The emergence of literature focused exclusively on machine-learning and predictive algorithms is not encouraging in this respect, not least because those models are built upon a flawed evidence base.

Emerging principles for policy and practice

Our interpretation of the evidence suggests that to design services that are more equitable and account for the complex reasons underlining missingness, systems should be designed to identify ‘missing’ patients and interventions tailored to the needs of these patients. Papers included in this review suggest a need to identify and actively reach out to patients experiencing missingness to discuss their candidacy experiences, both to allow tailoring of interventional approaches and to support service design based on patient experience. Dumontier et al. [9] and others suggest that these conversations help build a local evidence base and act as a first line of intervention:

“Personal, respectful, and supportive contact both improves health care providers’ understanding of their patients’ individual and collective issues and may decrease anxiety that those patients may have about seeking care.” (p.640).

Others suggest proactive, structured assessments of domains related to non-attendance (e.g. mental health, particularly depression and anxiety [33, 106, 110, 129]; post-traumatic stress disorder, attachment and Adverse Childhood Experiences [8, 11, 33]; or ‘patient activation’ [58, 164]) or more holistic assessments of patients’ needs and circumstances [41, 105, 163]. Interventions can then be designed with these patients in mind, tailored to them, or evaluated according to effectiveness or appropriateness for ‘missing’ patients [8, 9, 31, 33, 39, 41, 42, 58, 71, 72, 105, 110, 129, 130]. Without tailoring, interventions designed to address missed appointments risk worsening inequalities of access [13, 18, 27, 59, 63, 69, 81, 95, 98, 117, 148, 155, 165,166,167,168,169,170,171,172].

Tailoring and targeting of interventions will be more beneficial if they target multiple causal domains and the interaction between patients and services. Often, policy and practice are designed to tackle a single domain identified in the literature and often focus solely on patient cognition or behaviour—for example, using reminders for forgetfulness or behavioural “nudges” to encourage the ‘correct’ patient behaviour [3, 119, 162, 173,174,175,176]. These perpetuate the inaccurate and stigmatising notion that patients are the primary cause of non-attendance, precluding action on other influences. Targeting one domain in isolation is unlikely to resolve the multiple, overlapping causes of missingness outlined here, and any complex intervention must go beyond perspectives on patients’ behaviours to address structural forces, service design and organisational cultures [27, 39, 40, 98, 104, 122, 174].

The evidence above shows that missingness is driven by dynamics where patients feel unheard, disempowered, unsafe or threatened. Promoting relational, cultural and structural safety involves identifying and addressing problematic relational dynamics and power differentials within services, while acknowledging how patients’ candidacies are impacted by the intersections of their broader relational, cultural and structural circumstances [10, 11, 40, 42, 44, 45, 59, 71, 87, 103, 104, 120, 177, 178]. Work is required to address how stigma, judgement and dehumanisation are communicated or to address the mistrust caused by relational difficulties or wider social exclusion [41, 42, 44, 46, 66, 69, 71, 93, 96, 101, 105, 108, 111, 117, 163]. Building on trauma-informed, patient-centred and culturally safe principles, healthy relationships have benefits in themselves and act as the scaffolding upon which other interventions can be built [11, 32, 40, 42, 44, 45, 57, 59, 66, 71, 87, 90, 94, 101, 120, 122, 163, 179].

Conclusions

This realist review has sought to identify and understand the factors which lead to multiple missed appointments, differentiating the situational causal dynamics of single missed appointments from the enduring dynamics that underpin ‘missingness.’ Patients may not attend because of a belief that services and their offerings are not “for them”—not suitable, beneficial or appropriate for their needs or their identities. This can reflect a lifetime of experiences with services as well as other meaningful relationships that shape patients’ sense of self in relation to health services and to caring relationships. Attendance may not feel beneficial or worthwhile, or it may be a source of unmanageable anxiety or threat. Negative past relational experiences and anticipated future difficulties, including disempowerment, hostility and stigma, make patients feel unsafe and unwelcome. Processes of prioritisation for those exposed to multiple, competing demands and urgencies can interfere with healthcare, and patients’ resources may be insufficient to support the management of competing candidacies or the logistics of attendance. Appointment systems may prevent access to timely, convenient, relationally accessible care. These domains overlap and mutually reinforce, and the content, configuration and relative influence of each vary between patients and settings.

The strength of realist review is in its theory-driven synthesis of a diverse evidence base, creating a coherent, evidence-informed narrative to inform future action. The use of candidacy and fundamental causation has led to a rich and nuanced understanding of the multiple, overlapping influences in missingness, which operate at the micro-, meso- and macro-level. The main limitations of this review relate to the evidence base. The reliance on administrative data and surveys/questionnaires, and the lack of a missingness perspective in research design and reporting, means that parents experiencing missingness are also ‘missing’ from research and public policy conversations around healthcare provision. Realist review allows for some of these gaps to be addressed and enables us to draw inferences from a wide evidence base. There remains a need for new research to broaden and deepen this evidence base so that those seeking to address missingness can act from firm foundations.

There is a need to reframe the problem from one of patient behaviour causing challenges for services and towards an understanding of issues in access/quality in the interaction between patients and services. Moreover, if missingness is an issue of access to and quality of care, it is only one part of the mutually reinforcing relationship between socio-economic status and health. We have to stay open to the important challenge of what contribution this emphasise on service provision makes when wider structural factors are so pervasive [104]. Health services need to be at their best where they are needed most to have a chance of doing this and reversing the inverse care law [180].

Availability of data and materials

The papers reported in the realist evidence synthesis are listed in the supplementary file along with the CMOCs which underpin the results. When the paper is published these will be available on the overall study Openscience Framework webpage.

Abbreviations

- CMO or CMOC:

-

Context-Mechanism-Outcome or Context-Mechanism-Outcome Configuration

- GP:

-

General practice/general practitioner

- NHS:

-

National Health Service

- NIHR:

-

National Institute for Health and Care Research

- PTSD:

-

Post-traumatic stress disorder

- RAMESES:

-

Realist And MEta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards

References

NHS Borders. Going to miss your appointment? Let us know and we’ll give it to someone else: NHS Borders; 2016. https://www.nhsborders.scot.nhs.uk/missedappointments?platform=hootsuite. [accessed 29.04.2024]

NHS England. NHS Long Term Plan 2019. https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/. [accessed 29.04.2024].

Martin SJ, Bassi S, Dunbar-Rees R. Commitments, norms and custard creams - a social influence approach to reducing did not attends (DNAs). J R Soc Med. 2012;105(3):101–4.

Fairhurst K, Sheikh A. Texting appointment reminders to repeated non-attenders in primary care: randomised controlled study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(5):373–6.

Shah SJ, Cronin P, Hong CS, Hwang AS, Ashburner JM, Bearnot BI, et al. Targeted reminder phone calls to patients at high risk of no-show for primary care appointment: a randomized trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(12):1460–6.

Kurasawa H, Hayashi K, Fujino A, Takasugi K, Haga T, Waki K, et al. Machine-learning-based prediction of a missed scheduled clinical appointment by patients with diabetes. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2016;10(3):730–6.

Carreras-García D, Delgado-Gómez D, Llorente-Fernández F, Arribas-Gil A. Patient no-show prediction: a systematic literature review. Entropy. 2020;22(6):675.

Traeger L, O’Cleirigh C, Skeer MR, Mayer KH, Safren SA. Risk factors for missed HIV primary care visits among men who have sex with men. J Behav Med. 2012;35(5):548–56.

DuMontier C, Rindfleisch K, Pruszynski J, Frey JJ. A multi-method intervention to reduce no-shows in an urban residency clinic. Fam Med. 2013;45(9):634–41.

Cashman SB, Savageau JA, Lemay CA, Ferguson W. Patient health status and appointment keeping in an urban community health center. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004;15(3):474–88.

Chapman KA, Machado SS, van der Merwe K, Bryson A, Smith D. Exploring primary care non-attendance: a study of low-income patients. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13

Shimotsu S, Roehrl A, McCarty M, Vickery K, Guzman-Corrales L, Linzer M, et al. Increased likelihood of missed appointments (“no shows”) for racial/ethnic minorities in a safety net health system. J Prim Care Community Health. 2016;7(1):38–40.

Parker MM, Moffet HH, Schillinger D, Adler N, Fernandez A, Ciechanowski P, et al. Ethnic differences in appointment-keeping and implications for the patient-centered medical home: findings from the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). Health Serv Res. 2012;47(2):572–93.

Samuels RC, Ward VL, Melvin P, Macht-Greenberg M, Wenren LM, Yi J, et al. Missed appointments: factors contributing to high no-show rates in an urban pediatrics primary care clinic. Clin Pediatr. 2015;54(10):976–82.

Williamson AE, McQueenie R, Ellis DA, McConnachie A, Wilson P. ‘Missingness’ in health care: associations between hospital utilization and missed appointments in general practice. A retrospective cohort study PLoS One. 2021;16(6): e0253163.

McQueenie R, Ellis DA, Fleming M, Wilson P, Williamson AE. Educational associations with missed GP appointments for patients under 35 years old: administrative data linkage study. BMC Med. 2021;19(1):219.

McQueenie R, Ellis DA, McConnachie A, Wilson P, Williamson AE. Morbidity, mortality and missed appointments in healthcare: a national retrospective data linkage study. BMC Med. 2019;17:9.

Ellis DA, McQueenie R, McConnachie A, Wilson P, Williamson AE. Demographic and practice factors predicting repeated non-attendance in primary care: a national retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet Public Health. 2017;2(12):E551–9.

Williamson AE, Ellis DA, Wilson P, McQueenie R, McConnachie A. Understanding repeated non-attendance in health services: a pilot analysis of administrative data and full study protocol for a national retrospective cohort. BMJ Open. 2017;7(2):11.

Lindsay C, Baruffati D, Mackenzie M, Ellis DA, Major M, O’Donnell K, et al. A realist review of the causes of, and current interventions to address ‘missingness’ in health care. NIHR Open Research. 2023;3:33.

Gkiouleka A, Wong GF, Sowden S, Bambra C, Siersbaek R, Manji S, et al. Reducing health inequalities through general practice. Lancet Public Health. 2023;8(6):E463–72.

Pawson R, Greenhalgh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review-a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(1_suppl):21–34.

Duddy C, Wong G. Grand rounds in methodology: when are realist reviews useful, and what does a ‘good’realist review look like? BMJ Qual Saf. 2023;32:173–80.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Pawson R. Internet-based medical education: a realist review of what works, for whom and in what circumstances. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):1–10.

Wong G, Westhorp G, Greenhalgh J, Manzano A, Jagosh J, Greenhalgh T. Quality and reporting standards, resources, training materials and information for realist evaluation: the RAMESES II project. Health Services and Delivery Research. 2017;5(28):1–108.

Wong G, Greenhalgh T, Westhorp G, Pawson R. Development of methodological guidance, publication standards and training materials for realist and meta-narrative reviews: the RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses – Evolving Standards) project. NIHR Journals Library, Southampton (UK); 2014.

Amberger C, Schreyer D. What do we know about no-show behavior? A systematic, interdisciplinary literature review. J Econ Surv. 2024;38(1):57–96.

Dantas LF, Fleck JL, Cyrino Oliveira FL, Hamacher S. No-shows in appointment scheduling - a systematic literature review. Health Policy. 2018;122(4):412–21.

George A, Rubin G. Non-attendance in general practice: a systematic review and its implications for access to primary health care. Fam Pract. 2003;20(2):178–84

Parsons J, Bryce C, Atherton H. Which patients miss appointments with general practice and the reasons why: a systematic review. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(707):E406–12.

Sun CA, Taylor K, Levin S, Renda SM, Han HR. Factors associated with missed appointments by adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2021;9(1):e001819.

Wilson R, Winnard Y. Causes, impacts and possible mitigation of non-attendance of appointments within the National Health Service: a literature review. J Health Organ Manag. 2022;36(7):892–911.

Ciechanowski P, Russo J, Katon W, Simon G, Ludman E, Von Korff M, et al. Where is the patient? The association of psychosocial factors and missed primary care appointments in patients with diabetes. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28(1):9–17.

Ellis DA, McQueenie R, McConnachie A, Wilson P, Williamson A. Non-attending patients in general practice. Lancet Public Health. 2018;3(3):e113.

Hussain-Gambles M, Neal RD, Dempsey O, Lawlor DA, Hodgson J. Missed appointments in primary care: questionnaire and focus group study of health professionals. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(499):108–13.

Neal RD, Hussain-Gambles M, Allgar VL, Lawlor DA, Dempsey O. Reasons for and consequences of missed appointments in general practice in the UK: questionnaire survey and prospective review of medical records. BMC Fam Pract. 2005;6:47.

Margham T. Reducing missed appointments in general practice: evaluation of a quality improvement programme in East London. Br J Gen Pract. 2021;71(704):109.

Philpott-Morgan S, Thakrar DB, Symons J, Ray D, Ashrafian H, Darzi A. Characterising the nationwide burden and predictors of unkept outpatient appointments in the National Health Service in England: a cohort study using a machine learning approach. PLoS Med. 2021;18(10):e1003783.

Garuda SR, Javalgi RG, Talluri VS. Tackling no-show behavior: a market-driven approach. Health Mark Q. 1998;15(4):25–44.

McLean S, Gee M, Booth A, Salway S, Nancarrow S, Cobb M, et al. Targeting the use of reminders and notifications for uptake by populations (TURNUP): a systematic review and evidence synthesis. Health Services and Delivery Research. 2014;2(34):1–84.

Ballantyne M, Liscumb L, Brandon E, Jaffar A, Macdonald A, Beaune L. Mothers’ perceived barriers to and recommendations for health care appointment keeping for children who have cerebral palsy. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2019;6.

van Baar JD, Joosten H, Car J, Freeman GK, Partridge MR, van Weel C, et al. Understanding reasons for asthma outpatient (non)-attendance and exploring the role of telephone and e-consulting in facilitating access to care: exploratory qualitative study. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15(3):191–5.

Fiori KP, Heller CG, Rehm CD, Parsons A, Flattau A, Braganza S, et al. Unmet social needs and no-show visits in primary care in a US northeastern urban health system, 2018–2019. Am J Public Health. 2020;110:S242–50.

Cameron EZ, editor. A mixed methods investigation of parental factors in non-attendance at general paediatric hospital outpatient appointments. [Dissertation] Birmingham, Aston University; 2015. https://publications.aston.ac.uk/id/eprint/25145/.

Abdulkadir LS, Mottelson IN, Nielsen DS. Why does the patient not show up? Clinical case studies in a Danish migrant health clinic. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc. 2019;7(2):316–24.

Brewster SZ. The role of community pharmacy in supporting people with diabetes who have a history of repeated non-attendance at healthcare appointments. Dissertation, University of Southampton; 2023.

Claveau J, Authier M, Rodrigues I, Crevier-Tousignant M. Patients’ missed appointments in academic family practices in Quebec. Can Fam Physician. 2020;66(5):349–55.

Poll R, Allmark P, Tod AM. Reasons for missed appointments with a hepatitis C outreach clinic: a qualitative study. Int J Drug Policy. 2017;39:130–7.

Ayalde J, Soong W, Thomas S, McCann P, Griffiths J, Nicholls C, et al. Reasons for non-attendance in youth mental health clinics: insights from mobile messaging communications. Early Interv Psychiatry. 2023;17(9):877–83.

Leavey G, Vallianatou C, Johnson-Sabine E, Rae S, Gunputh V. Psychosocial barriers to engagement with an eating disorder service: a qualitative analysis of failure to attend. Eat Disord. 2011;19(5):425–40.

Bean AG, Talaga J. Appointment breaking: causes and solutions. J Health Care Mark. 1992;12(4):14–25.urce>

Harrington EE, Reese-Melancon C, Bock JE. Sometimes they show, sometimes they don’t: appointment attendance as a naturalistic prospective memory task. Appl Cogn Psychol. 2023;37(3):590–9.

Dyer BT, Swann F, Kadam M, Draper J, Mc Gill LA, Kapetanakis S, et al. Understanding non-attendance to an inner city tertiary centre heart failure clinic: a pilot project. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(Supplement 1):3747.

Mault S, McDonough BJ, Currie P, Burhan H. Reasons proffered for non-attendance at a difficult asthma clinic. Thorax. 2012;67(SUPPL. 2):A187.

Kaplan-Lewis E, Percac-Lima S. No-show to primary care appointments: why patients do not come. J Prim Care Community Health. 2013;4(4):251–5.

Simmons D, Clover G. A case control study of diabetic patients who default from primary care in urban New Zealand. Diabetes Metab. 2007;33(2):109–13.

Bansal I, Soni R, Eisen S, Ward A, Longley N, Sen C. 464 Breaking the barriers to accessing care: co-creating solutions with refugee service users. Arch Dis Child. 2023;108:A411.

Barker I, Steventon A, Williamson R, Deeny SR. Self-management capability in patients with long-term conditions is associated with reduced healthcare utilisation across a whole health economy: cross-sectional analysis of electronic health records. BMJ Qual Saf. 2018;27(12):989–99.

Jefferson L, Atkin K, Sheridan R, Oliver S, Macleod U, Hall G, et al. Non-attendance at urgent referral appointments for suspected cancer: a qualitative study to gain understanding from patients and GPs. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(689):E850–9.

Liu S, Ng JKY, Moon EH, Morgan D, Woodhouse N, Agrawal D, et al. Impact of COVID-19-associated anxiety on the adherence to intravitreal injection in patients with macular diseases a year after the initial outbreak. Ther Adv Ophthalmol. 2022;14:1–12.

Lyon R, Reeves PJ. An investigation into why patients do not attend for out-patient radiology appointments. Radiography. 2006;12(4):283–90.

Eades C, Alexander H. A mixed-methods exploration of non-attendance at diabetes appointments using peer researchers. Health Expect. 2019;22(6):1260–71.

Sun CA, Shenk Z, Renda S, Maruthur N, Zheng S, Perrin N, et al. Experiences and perceptions of telehealth visits in diabetes care during and after the COVID-19 pandemic among adults with type 2 diabetes and their providers: qualitative study. JMIR diabetes. 2023;8:e44283–e.

Howarth AR, Apea V, Michie S, Morris S, Sachikonye M, Mercer CH, et al. Associations with sub-optimal clinic attendance and reasons for missed appointments among heterosexual women and men living with HIV in London. AIDS Behav. 2022;26(11):3620–9.

Gurewich D, Linsky AMM, Harvey KLL, Li M, Griesemer I, MacLaren RZZ, et al. Relationship between unmet social needs and care access in a veteran cohort. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(SUPPL 3):841–8.

Akter S, Doran F, Avila C, Nancarrow S. A qualitative study of staff perspectives of patient non-attendance in a regional primary healthcare setting. Australas Med J. 2014;7(5):218–26.

Macharia WM. An overview of interventions to improve compliance with appointment keeping for medical services. JAMA. 1992;267(13):1813–7.

Cameron E, Heath G, Redwood S, Greenfield S, Cummins C, Kelly D, et al. Health care professionals’ views of paediatric outpatient non-attendance: implications for general practice. Fam Pract. 2014;31(1):111–7.

Crane MA, Cetrano G, Joly LMA, Coward S, Daly BJM, Ford C, et al. Mapping of specialist primary health care services in England for people who are homeless. Summary of findings and considerations for health service commissioners and providers. 2018. Social Care Workforce Research Unit, King’s College London. https://doi.org/10.18742/pub01-091

Brown S. Qualitative evaluation of focused care. Focused Care, 2019. https://focusedcare.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/FC-Qualitative-Eval.pdf . [Accessed 29.04.2024].

McCarthy L, Parr S, Green S, Reeve K. Understanding models of support for people facing multiple disadvantage: a literature review. 2020. Fulfilling Lives Lambeth, Southwark & Lewisham. https://www.shu.ac.uk/centre-regional-economic-social-research/publications/understanding-models-of-support-for-people-facing-multiple-disadvantage-a-literature-review. [accessed 29.04.2024].

Izard T. Managing the habitual no-show patient. Fam Pract Manag. 2005;12(2):65–6.

Waller J, Hodgkin P. Defaulters in general practice: who are they and what can be done about them? Fam Pract. 2000;17(3):252–3.

Pawson R. Digging for nuggets: how ‘bad’ research can yield ‘good’ evidence. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2006;9(2):127–42.

Freese J, Lutfey K. Fundamental causality: challenges of an animating concept for medical sociology. In: Pescosolido B, Martin J, McLeod J, Rogers A, editors. Handbook of the sociology of health, illness, and healing: A blueprint for the 21st century. New York: Springer; 2010. p. 67–81.

Lutfey K, Freese J. Toward some fundamentals of fundamental causality: socioeconomic status and health in the routine clinic visit for diabetes. Am J Sociol. 2005;110(5):1326–72.

Clouston SA, Link BG. A retrospective on fundamental cause theory: state of the literature and goals for the future. Annu Rev Sociol. 2021;47:131–56.

Dixon-Woods M, Cavers D, Agarwal S, Annandale E, Arthur A, Harvey J, et al. Conducting a critical interpretive synthesis of the literature on access to healthcare by vulnerable groups. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2006;6:1–13.

Mackenzie M, Conway E, Hastings A, Munro M, O’Donnell CA. Intersections and multiple ‘candidacies’: exploring connections between two theoretical perspectives on domestic abuse and their implications for practicing policy. Soc Policy Soc. 2015;14(1):43–62.

Mackenzie M, Conway E, Hastings A, Munro M, O’Donnell C. Is ‘Candidacy’ a useful concept for understanding journeys through public services? A critical interpretive literature synthesis. Soc Policy Adm. 2013;47(7):806–25.

Herber OR, Smith K, White M, Jones MC. ‘Just not for me’–contributing factors to nonattendance/noncompletion at phase III cardiac rehabilitation in acute coronary syndrome patients: a qualitative enquiry. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26(21–22):3529–42.

Hamilton W. Non-attendance in general practice: a questionnaire. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2002;3(4):226–30.

Deyo RA, Inui TS. Dropouts and broken appointments. A literature review and agenda for future research. Med Care. 1980;18(11):1146–57.

Roberts L, Garo-Falides J, Bowran H. Non-attendance in musculoskeletal outpatients: the good, the bad and the ugly. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom). 2015;101(SUPPL. 1):eS1289–90.

Minshall I, Neligan A. A review of people who did not attend an epilepsy clinic and their clinical outcomes. Seizure. 2017;50:121–4.

Zailinawati AH, Ng CJ, Nik-Sherina H. Why do patients with chronic illnesses fail to keep their appointments? A telephone interview. Asia-Pac J Public Health. 2006;18(1):10–5.

Thapar A, Ghosh A. Non-attendance at a psychiatric clinic. Psychiatr Bull. 1991;15(4):205–6.

Prudden G. Quality improvement project exploring the factors in non-attendance at an NHS musculoskeletal outpatients department. Physiotherapy (United Kingdom). 2021;113(Supplement 1):e151–2

Unger K, Lesiuk A, Unger S. 947 How do we save£ 1200 lost to DNAs’ per complex paediatric respiratory clinic and protect our most vulnerable patients? Arch Dis Child. 2023;108:A441.

Barron WM. Failed appointments - who misses them, why are they missed, and what can be done. Prim Care. 1980;7(4):563–74.

Bickler CB. Defaulted appointments in general practice. J R Coll Gen Pract. 1985;35(270):19–22.

Stevenson JS. Appointment systems in general practice: how patients use them. BMJ. 1967;2(5555):827.

Koester KA, Johnson MO, Wood T, Fredericksen R, Neilands TB, Sauceda J, et al. The influence of the ‘good’ patient ideal on engagement in HIV care. PLoS One. 2019;14(3):e0214636.

Biggs J, Njoku N, Kurtz K, Omar A. reasing missed appointments at a community health center: a community collaborative project. J Prim Care Community Health. 2022;13:3.

Anyaegbu CT. SMS reminders: reducing DNA at a community mental health depot clinic. J Commun Nurs. 2021;35(1):50–55.

Finlayson S, Boelman V, Young R, Kwan A. Saving lives, saving money: how homeless health peer advocacy reduces health inequalities. Groundswell; 2015. https://groundswell.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Groundswell-Saving-Lives-Saving-Money-Full-Report-Web-2016.pdf. [accessed 30.04.2024].

Blankenstein R. Failed appointments - do telephone reminders always work? Clin Gov. 2003;8(3):208–12

Buetow S. Non-attendance for health care: when rational beliefs collide. Sociol Rev. 2007;55(3):592–610.

Horigan G, Davies M, Findlay-White F, Chaney D, Coates V. Reasons why patients referred to diabetes education programmes choose not to attend: a systematic review. Diabet Med. 2017;34(1):14–26.

Cosgrove MP. Defaulters in general practice: reasons for default and patterns of attendance. Br J Gen Pract. 1990;40(331):50–2.

Aspinall PJ. Inclusive practice: vulnerable migrants, gypsies and travellers, people who are homeless, and sex workers: a review and synthesis of interventions/service models that improve access to primary care & reduce risk of avoidable admission to hospital. University of Kent; 2014. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5a7db8b2e5274a5eaea65ee4/Inclusive_Practice.pdf. [accessed 30.04.2024].

Lacy NL, Paulman A, Reuter MD, Lovejoy B. Why we don’t come: patient perceptions on no-shows. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(6):541–5.

Mahmood FZ. Exploring reasons for clients’ non-attendance at appointments within a community-based alcohol service: clients’ and practitioners’ perspectives. Dissertation, Manchester Metropolitan University, 2021.

Arnold OF. Reconsidering the “NO SHOW” stamp: increasing cultural safety by making peace with a colonial legacy. Northern Review. 2012;36:77–96.

Gunner E, Chandan SK, Marwick S, Saunders K, Burwood S, Yahyouche A, et al. Provision and accessibility of primary healthcare services for people who are homeless: a qualitative study of patient perspectives in the UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(685):e526–36.

Moscrop A, Siskind D, Stevens R. Mental health of young adult patients who do not attend appointments in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Fam Pract. 2012;29(1):24–9.

Winkley K, Evwierhoma C, Amiel SA, Lempp HK, Ismail K, Forbes A. Patient explanations for non-attendance at structured diabetes education sessions for newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes: a qualitative study. Diabet Med. 2015;32(1):120–8.

Pakhomova TEE, Nicholson V, Fischer M, Ferguson J, Moore DMM, Salters K, et al. Exploring primary healthcare experiences and interest in mobile technology engagement amongst an urban population experiencing barriers to care. Qual Health Res. 2023;33(8–9):765–77.

Marshall D, Quinn C, Child S, Shenton D, Pooler J, Forber S, et al. What IAPT services can learn from those who do not attend. J Ment Health. 2016;25(5):410–5.

Gonzalez JS, Peyrot M, McCarl LA, Collins EM, Serpa L, Mimiaga MJ, et al. Depression and diabetes treatment nonadherence: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2398–403.

Vetter I. Primary health care for people with multiple and complex needs: what does best practice look like? Fulfilling Lives/University of Brighton, 2020. https://www.bht.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/Primary-Healthcare-What-does-best-practice-look-like-May-2020.pdf. [accessed 30.04.2024].

Tonnesen M, Hedeager Momsen A-M. Bridging gaps in health? A qualitative study about bridge-building and social inequity in Danish healthcare. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2023;18(1):2241235.

Revolving Doors Agency. Navigating complexity: learning from Navigators across Birmingham. Revolving Doors Agency, 2020. https://www.tnlcommunityfund.org.uk/media/insights/documents/Navigating-Complexity-Learning-from-the-navigators-across-Birmingham-2020.pdf?mtime=20220601114929&focal=none. [accessed 30.04.2024].

Parkes T, Matheson C, Carver H, Foster R, Budd J, Liddell D, et al. A peer-delivered intervention to reduce harm and improve the well-being of homeless people with problem substance use: the SHARPS feasibility mixed-methods study. Health Technol Assess. 2022;26(14):1–128.

Martin C, Perfect T, Mantle G. Non-attendance in primary care: the views of patients and practices on its causes, impact and solutions. Fam Pract. 2005;22(6):638–43.

Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(5):813–21.

Wilson B, Astley P. Gatekeepers: access to primary care for those with multiple need. VOICES, Healthwatch and Expert Citizens, 2016.

Maggs C, Langley C. Why patients miss primary care appointments: involving patients in research. Prim Health Care. 2008;18(2):34–7.

Ruggeri K, Folke T, Benzerga A, Verra S, Buttner C, Steinbeck V, et al. Nudging New York: adaptive models and the limits of behavioral interventions to reduce no-shows and health inequalities. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Department for Levelling Up. Frontline support models for people experiencing multiple disadvantage: A Rapid Evidence Assessment. London: HMSO. April 2023. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/642af3507de82b000c31350c/Changing_Futures_Evaluation_-_Frontline_support_models_REA.pdf. [accessed 30.04.2024].

Lawal MO. Non-attendance in diabetes education centres: perceptions of patients and education providers. Diabet Med. 2014;31(SUPPL. 1):102–3.

Wilsey KZ. Why patients miss appointments at an integrated primary care clinic. Dissertation, Antioch University, 2020. [accessed 30.04.2024]

Sharp DJ, Hamilton W. Non-attendance at general practices and outpatient clinics. BMJ (Clinical research ed). 2001;323(7321):1081–2.

Change booking system to cut DNAs. Practice Nurse. 2020;50(10):6.

Ullah S, Rajan S, Liu T, Demagistris E, Jahrstorfer R, Anandan S, et al. Why do patients miss their appointments at primary care clinics. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2018;4(3):1–5.

Shahab I, Meili R. Examining non-attendance of doctor’s appointments at a community clinic in Saskatoon. Can Fam Physician. 2019;65(6):E264–8.

Denneny EK, Black SE, Bogle Y, Macavei VM, O’Shaughnessy TC, White VLC, et al. Tackling poor attendance to tuberculosis clinic-who, why and what can be done. Thorax. 2014;69(SUPPL. 2):A210

Pal B, Taberner DA, Readman LP, Jones P. Why do outpatients fail to keep their clinic appointments? Results from a survey and recommended remedial actions. Int J Clin Pract. 1998;52(6):436–7.

Bowser DM, Utz S, Glick D, Harmon R. A systematic review of the relationship of diabetes mellitus, depression, and missed appointments in a low-income uninsured population. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2010;24(5):317–29.

Campbell K, Millard A, McCartney G, McCullough S. Who is least likely to attend? An analysis of outpatient appointment ‘did not attend’(DNA) data in Scotland. Edinburgh: NHS Health Scotland. 2015. https://www.healthscotland.scot/media/1129/5348_dna-analysis_nhs-ggc.pdf. [accessed 30.04.2024].

Boshers EB, Cooley ME, Stahnke B. Examining no-show rates in a community health centre in the United States. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30(5):e2041–9.

Magan T, Kirmani A, Robertson M, Mohamed M, Mann S. Non-attendance in the ranibizumab treatment clinic for diabetic macular oedema: Rates and reasons. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2014;24(3):465–6.

Mason C. Non-attendance at out-patient clinics: a case study. J Adv Nurs. 1992;17(5):554–60.

Campbell-Richards D. Exploring diabetes non-attendance: an Inner London perspective. J Diabetes Nurs. 2016;20(2):73–8.

Hickmott S, Stroud T. Hidden dimensions. The complexities of podiatry clinic non attendance of people with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2009;26(SUPPL.1):174.

Lawal M, Woodman A. Socio-demographic determinants of attendance in diabetes education centres: a survey of patients’ views. Eur Med J Diabetes. 2021;9(1):102–9.

Arber S, Sawyer L. Do appointment systems work? BMJ. 1982;284(6314):478–80.

Sharp L, Cotton S, Thornton A, Gray N, Cruickshank M, Whynes D, et al. Who defaults from colposcopy? A multi-centre, population-based, prospective cohort study of predictors of non-attendance for follow-up among women with low-grade abnormal cervical cytology. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 2012;165(2):318–25.

Corrigan PW, Pickett S, Schmidt A, Stellon E, Hantke E, Kraus D, et al. Peer navigators to promote engagement of homeless African Americans with serious mental illness in primary care. Psychiatry Res. 2017;255:101–3.

Healthwatch. Cost of living: People are increasingly avoiding NHS appointments and prescriptions. Healthwatch. 2023. https://www.healthwatch.co.uk/news/2023-01-09/cost-living-people-are-increasingly-avoiding-nhs-appointments-and-prescriptions.[accessed 30.04.2024].

Guo JF, Bard JJ, Morrice D, Jaen CR, Poursani R. Offering transportation services to economically disadvantaged patients at a family health center: a case study. Health Syst. 2022;11(4):251–75.

Dockery F, Rajkumar C, Chapman C, Bulpitt C, Nicholl C. The effect of reminder calls in reducing non-attendance rates at care of the elderly clinics. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77(903):37–9.

Hull AM, Alexander DA, Morrison F, McKinnon JS. A waste of time: non-attendance at out-patient clinics in a Scottish NHS Trust. Health Bull (Edinb). 2002;60(1):62–9.

Jones MC, Smith K, Herber O, White M, Steele F, Johnston DW. Intention, beliefs and mood assessed using electronic diaries predicts attendance at cardiac rehabilitation: an observational study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;88:143–52.

Lakshminarayana I. Measures to improve non attendance rates of community paediatric outpatient clinics. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101(Supplement 1):A106.

Mitchell AJ, Selmes T. A comparative survey of missed initial and follow-up appointments to psychiatric specialties in the United kingdom. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(6):868–71.

Morris L, Haywood S. Why do patient miss appointments? A retrospective population study in paediatric outpatients in a metropolitan hospital. Arch Dis Child. 2014;99(SUPPL. 1):A96.

Nguyen DL, Dejesus RS, Wieland ML. Missed appointments in resident continuity clinic: patient characteristics and health care outcomes. J Grad Med Educ. 2011;3(3):350–5.

Tait J, Noyes K, Bath L, Henderson M, Elleri D. Clinic non-attendance, glycaemic control and deprivation score in paediatric and young persons’ diabetes clinics in Lothian, Scotland. Pediatr Diabetes. 2017;18(Supplement 25):88.

Weltermann BM, Doost SM, Kersting C, Gesenhues S. Hypertension management in primary care: how effective is a telephone recall for patients with low appointment adherence in a practice setting? Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2014;126(19–20):613–8.

Williamson AE, Mullen K, Wilson P. Understanding, “revolving door” patients in general practice: a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15:1–11.

Practice Nurse. Missing appointments increases risk of death. Pract Nurse. 2019;49(1):10.

Qin J, Chan CW, Dong J, Homma S, Ye S. Telemedicine is associated with reduced socioeconomic disparities in outpatient clinic no-show rates. J Telemed Telecare. 2023:0(0).

Woodcock EW. Managing your appointment ‘no-shows.’ J Med Pract Manag. 2000;15:284–8.

Kiruparan P, Kiruparan N, Debnath D. Impact of pre-appointment contact and short message service alerts in reducing ‘Did Not Attend’ (DNA) rate on rapid access new patient breast clinics: a DGH perspective. BMC Health Serv Research. 2020;20(1):9.

Moscrop A. Would it be a good idea to charge for missed appointments at the doctors surgery? BMJ Opinion. 2015;351:23.

Taylor B. Patient use of a mixed appointment system in an urban practice. BMJ. 1984;289(6454):1277–8.

Corfield L, Schizas A, Williams A, Noorani A. Non-attendance at the colorectal clinic: a prospective audit. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2008;90(5):377–80.

Royal College of General Practitioners. Charging for missed appointments won’t address intense GP pressures. Royal College of General Practitioners, 2022. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/news/missed-appointments [accessed 30.04.2024]

Royal College of General Practitioners. Missed GP appointments are frustrating – but there may be underlying reasons why patients don't turn up, says College. Royal College of General Practitioners, 2020. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/news/missed-gp-appointments. [accessed 08.03.2023].

Royal College of General Practitioners. Charging for GP appointments would have the biggest impact on vulnerable patients, says College Chair. Royal College of General Practitioners, 2023. https://www.rcgp.org.uk/News/GP-appointment-charges-response#:~:text=However%2C%20the%20College%20does%20not,already%20working%20under%20immense%20pressures. [accessed 30.04.2024].

Bull SL, Frost N, Bull ER. Behaviourally informed, patient-led interventions to reduce missed appointments in general practice: a 12-month implementation study. Fam Pract. 2023;40(1):16–22.

Coulter A, Roberts S, Dixon A. Delivering better services for people with long-term conditions: Building the house of care. The King’s Fund, 2013. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/insight-and-analysis/reports/better-services-people-long-term-conditions. [accessed 30.04.2024].

Ogunyemi AO. Reducing the prevalence of missed primary care appointments in community health centers. Dissertation, University of Southern California; 2020.

McLean SM, Booth A, Gee M, Salway S, Cobb M, Bhanbhro S, et al. Appointment reminder systems are effective but not optimal: results of a systematic review and evidence synthesis employing realist principles. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2016;10:479–99.

Opon SO, Tenambergen WM, Njoroge KM. The effect of patient reminders in reducing missed appointment in medical settings: a systematic review. PAMJ-One Health. 2020;2(9).

Gurol-Urganci I, de Jongh T, Vodopivec-Jamsek V, Car J. Mobile phone messaging reminders for attendance at healthcare appointments. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;2013(12):CD007458.

Martin PM. Coroner inquest into ‘hospital non-attendance’ management in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69(681):195.

Raja L, Wagner S, Struyven R, Cortina-Borja M, Keane PA, Huemer J, et al. Determinants of non-attendance in synchronous teleophthalmology clinics. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2022;63(7):1412–A0108

Chen K, Zhang C, Gurley A, Jackson H, Akkem S. Appointment non-attendance for telehealth versus in-person primary care visits at a large public healthcare system. J Genl Intern Med. 2023;38(4):922–8

Morris J, Campbell-Richards D, Wherton J, Sudra R, Vijayaraghavan S, Greenhalgh T, et al. Webcam consultations for diabetes: findings from four years of experience in Newham. Pract Diabetes. 2017;34(2):45–50.

Sumarsono A, Case M, Kassa S, Moran B. Telehealth as a tool to improve access and reduce no-show rates in a large safety-net population in the USA. Bull N Y Acad Med. 2023;100(2):398–407.

Aggarwal A, Davies J, Sullivan R. “Nudge” and the epidemic of missed appointments: can behavioural policies provide a solution for missed appointments in the health service? J Health Organ Manag. 2016;30(4):558–64.

Teo AR, Niederhausen M, Handley R, Metcalf EE, Call AA, Jacob RL, et al. Using nudges to reduce missed appointments in primary care and mental health: a pragmatic trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(SUPPL 3):894–904.

Schwebel FJ, Larimer ME. Using text message reminders in health care services: a narrative literature review. Internet Interv. 2018;13:82–104.

Prentice P. Missed appointments. Practice. Management. 2004;14(8):14.

Mackenzie M, Gannon M, Stanley N, Cosgrove K, Feder G. You certainly don’t go back to the doctor once you’ve been told,“I’ll never understand women like you.”’Seeking candidacy and structural competency in the dynamics of domestic abuse disclosure. Sociol Health Illn. 2019;41(6):1159–74.

Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, Walker C, Loring B, Paine S-J, et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Int J Equity Health. 2019;18(1):1–17.

Wang Y, Baidoo FA. Design of integral reminder for collaborative appointment management. 50th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (HICSS). 2017:910–9.

Hart JT. The inverse care law. The Lancet. 1971;297(7696):405–12.

Acknowledgements

Claire Duddy, formerly University of Oxford, was the information specialist co-investigator. She devised and conducted the literature searches.

Funding

This was funded by a National Institute of Health Research UK research grant; NIHR study identification 135034.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AEW, DAE, MM1, CAO’D, SAS, and GW conceived the study. CL curated the data, conducted the formal analysis, wrote the original draft manuscript and led on the final version for submission. GW was the methodology expert. AEW and GW validated the data. DB, MM1, DAE, MM2, CAO’D, SAS, AEW and GW reviewed, edited and agreed the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lindsay, C., Baruffati, D., Mackenzie, M. et al. Understanding the causes of missingness in primary care: a realist review. BMC Med 22, 235 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03456-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-024-03456-2