Abstract

Background

The two inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines, CoronaVac and BBIBP-CorV, have been widely used to control the COVID-19 pandemic. The influence of multiple factors on inactivated vaccine effectiveness (VE) during long-term use and against variants is not well understood.

Methods

We selected published or preprinted articles from PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, medRxiv, BioRxiv, and the WHO COVID-19 database by 31 August 2022. We included observational studies that assessed the VE of completed primary series or homologous booster against SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe COVID-19. We used DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models to calculate pooled estimates and conducted multiple meta-regression with an information theoretic approach based on Akaike’s Information Criterion to select the model and identify the factors associated with VE.

Results

Fifty-one eligible studies with 151 estimates were included. For prevention of infection, VE associated with study region, variants, and time since vaccination; VE was significantly decreased against Omicron compared to Alpha (P = 0.021), primary series VE was 52.8% (95% CI, 43.3 to 60.7%) against Delta and 16.4% (95% CI, 9.5 to 22.8%) against Omicron, and booster dose VE was 65.2% (95% CI, 48.3 to 76.6%) against Delta and 20.3% (95% CI, 10.5 to 28.0%) against Omicron; primary VE decreased significantly after 180 days (P = 0.022). For the prevention of severe COVID-19, VE associated with vaccine doses, age, study region, variants, study design, and study population type; booster VE increased significantly (P = 0.001) compared to primary; though VE decreased significantly against Gamma (P = 0.034), Delta (P = 0.001), and Omicron (P = 0.001) compared to Alpha, primary and booster VEs were all above 60% against each variant.

Conclusions

Inactivated vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection was moderate, decreased significantly after 6 months following primary vaccination, and was restored by booster vaccination. VE against severe COVID-19 was greatest after boosting and did not decrease over time, sustained for over 6 months after the primary series, and more evidence is needed to assess the duration of booster VE. VE varied by variants, most notably against Omicron. It is necessary to ensure booster vaccination of everyone eligible for SARS-CoV-2 vaccines and continue monitoring virus evolution and VE.

Trial registration

PROSPERO, CRD42022353272.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19), caused by SARS-CoV-2, is a global pandemic that has had multiple waves [1], and several variants of concern (VOCs) with global public health significance have emerged during the pandemic [2]. Given the high cost of relying completely on non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs), vaccination is an important pandemic response measure [3]. Several SARS-CoV-2 vaccines have received World Health Organization (WHO) Emergency Use Listing [4], including two China-produced inactivated vaccines, BBIBP-CorV (by Sinopharm, Beijing Institute of Biological Products Co., Ltd.) and CoronaVac (by Sinovac Life Sciences Co., Ltd.). These were the first inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines developed and are based on the wild‐type (WT) strain [5]; their quality, safety, and efficacy were shown in clinical trials to meet the WHO SARS-CoV-2 vaccines target product profile. Both for BBIBP-CorV and CoronaVac, two doses should be administered for primary immunization, and a booster dose may be considered 4–6 months after completion of the primary series, either heterologous or homologous doses can be used [6, 7]. Inactivated vaccines have been widely used in many countries since the earliest days of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine availability [8,9,10], systematic reviews and meta-analyses have reported real-world effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in certain periods, showing good effectiveness and acceptability generally [9, 11,12,13,14].

A growing number of studies are showing that vaccine effectiveness (VE) is influenced by factors such as time since vaccination, variants, vaccination strategies and number of doses [15,16,17,18]. However, there is currently a lack of meta-analysis of the effectiveness changes of inactivated vaccines after long-term vaccination, as well as the combined effect of related factors, no available meta-analysis perform meta-regression of multiple factors related to inactivated VE, making it difficult to explain whether and how a factor actually contributes to VE when there are other related factors, the influence of multiple factors on VE is not well understood [19,20,21].

Knowledge of VE and its influencing factors can help policymakers manage and adjust vaccination strategies, but additional evidence on inactivated VE is needed. We therefore conducted a systematic review with meta-analysis and multiple meta-regression to refine the evidence of effectiveness and related factors of primary series and homologous booster doses of inactivated COVID-19 VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19.

Methods

Our systematic review with meta-analysis followed the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) guidelines [22]; Additional file 1: Table S1 shows the MOOSE Checklist. The study is registered with PROSPERO, registration number CRD42022353272.

Data sources and search strategy

We searched without language restriction for studies published or preprinted by 31 August 2022 on inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine efficacy or effectiveness in PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, medRxiv, BioRxiv, and the WHO COVID-19 database VIEW-HUB website [23], which compiles searches of more than 100 databases. We searched for studies with multiple variations of the primary key search terms: [(“Effectiveness” OR “Efficacy” OR “Evaluation”) AND (COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR Coronavirus) AND (Vaccine OR Vaccination) AND (CoronaVac or Vero Cell or BBIBP or WIBP or Inactivated). The full search strategy is shown in Additional file 1: Table S2. Additionally, the reference lists of the inactivated vaccine meta-analysis articles were hand-searched.

Selection criteria

The selected studies met the following eligibility criteria: (a) observational study (prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case–control studies, and descriptive studies [mainly cross-sectional]); (b) assessing the effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines (CoronaVac or BBIBP-CorV) to prevent SARS-CoV-2 infection or COVID-19-related hospitalization, severe/critical outcomes, and death; (c) reporting VE or related estimates from primary series or homologous booster vaccination at least 14 days after the last dose; and (d) with an unvaccinated reference group. We excluded randomized clinical trials, systematic reviews, and case series; we excluded studies that used only immunoglobulin M (IgM) antibody tests to diagnose COVID-19, serological studies, studies that did not report results of VE or estimates or data that can calculate estimates, and studies that only used a vaccinated reference group. Retrieved articles were exported to EndNote Reference Library, version X9.3.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two independent reviewers (SX and JL) performed the data extraction and quality assessment, and discussed the discrepancies. A third investigator (HW) resolved the remaining discrepancies. We extracted and analyzed VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 infection had to have been confirmed by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) or antigen testing in accordance with the WHO recommendations [24]; studies did not clarify the test method, but confirmed infection cases were also included. Due to differences in national policies for diagnostic testing, infection generally refers to testing after the onset of symptoms, but in countries like China that have large-scale RT-PCR testing, infection includes asymptomatic, test-positive individuals.

Estimates of COVID-19-related hospitalization, severe COVID-19 cases, COVID-19-related intensive care unit (ICU) admission, and death due to COVID-19 from articles were included in the severe COVID-19 outcome of our study. From included articles, severe COVID-19 cases generally defined according to WHO, by any of the following: (1) oxygen saturation < 90% on room air; (2) in adults, signs of severe respiratory distress (accessory muscle use, inability to complete full sentences, respiratory rate > 30; breaths per minute), and in children, very severe chest wall indrawing, grunting, central cyanosis, or presence of any other general danger signs (inability to breastfeed or drink, lethargy or reduced level of consciousness, convulsions) in addition to the signs of pneumonia [25]. Severe COVID-19 cases frequently require hospitalization and, if ventilatory support is required for acute respiratory failure, admission to the ICU. Additionally, if an article included more than one of the severe outcome subtypes and overlapped, we only chose the large-scale one to avoid double counting.

If an article specified the predominant SARS-CoV-2 variant during the study period or the specific variant in the study population, and if the variant was a VOC, we associated the reported VOC with the study estimates. If an article did not mention a predominant variant, had more than one predominant variant, or the variant was not a VOC, we classified the variant as “other.” Data in one article was of the WT strain, and the study showed that antibodies in vaccine-induced serum largely retained neutralizing response against Alpha [26], so we merged the evaluation of the WT strain with the Alpha strain data. If an article did not clearly state the time between vaccination and outcome, we estimated the duration from the start or completion of vaccination in the study setting, based on the information given in the article. Some studies reported vaccine effectiveness data on multiple groups; we combined relevant data in the same study according to the needs of meta-analysis to avoid double counting.

We extracted study data into a Microsoft Excel data extraction tool. Data were basic information, including title, first author, publication year, and study design; characteristics of the study population, including number of participants, country (for representation of regional characteristics and NPI use, we grouped countries by WHO region for the meta-analysis), population type, age range (populations were divided into different age ranges for meta-analysis, ± 5 years if the original age range was not completely specified); predominant SARS-CoV-2 variant during the study period; vaccination status, including vaccine brand, number of doses (primary [full series] and booster vaccination was defined as at least 14 days since two or three doses), and time since last dose; and vaccine effectiveness outcomes, including adjusted estimates, and their 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs).

We evaluated the risk of bias using the Newcastle–Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for cohort and case–control studies. We assessed the quality of descriptive studies using a checklist recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) [27]. Cohort studies and case–control studies were classified as having low (7 scores), moderate (5–6 scores), or high (4 scores) risk of bias with an overall quality score of 9. For descriptive studies, we assigned values to each item of the AHRQ checklist with resulting scores that ranged from 0 to 11. We categorized these scores as low, moderate, and high risk of bias with scores of 8–11, 4–7, and 0–3, respectively.

Statistical analysis

We used DerSimonian and Laird random-effects models to calculate pooled estimates for subgroup analyses [28]: hazard ratios (HR), rate ratios (RR), or odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs, comparing SARS-CoV-2 infection or severe COVID-19 in primary and booster vaccinated participants against different variants by time since vaccination. For data reported as frequencies or proportions, estimates were calculated directly. Vaccine effectiveness was (1-pooled HR/RR/OR) × 100%, together with 95% CIs. For vaccine effectiveness of 100% in which 95% CIs were not estimable, or if there was no event in either group in a trial, we adjusted estimates and approximated 95% CIs using study data, adding 0.5 cases to each group [29]. Negative VEs with study bias after review were excluded. We evaluated publication bias using funnel plots, Begg’s test [30], and Egger’s test [31]. The trim and fill method was used to identify and correct funnel plot asymmetry arising from publication bias [32].

We conducted multiple meta-regression with restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation and Knapp-Hartung adjustment to identify the factors associated with VE after adjusting for other explanatory variables [33, 34]. We used an information theoretic approach based on Akaike’s Information Criterion with the small-sample correction (AICc) for model selection, a valid model selection method outperforms other conventional methods for multiple regression or multiple meta-regression [35, 36], models with the smaller Δi (the difference units between the minimum AICc value model and the ith model) were more likely to be the potential best models, Δi values close to 0 have a lot of empirical support, and in the rough range, 4–7 have considerably less support [37], simply dropping models with ∆AIC will probably discard useful models [38]. Thus, we used multimodel inference to examine all possible factors combinations [36], and selected the top potential best models based on Δi values ranged 0–4, then decided the best model among potential ones by the coefficient of determination (R2) value of meta-regression, which represents the percentage of between-study heterogeneity explained by the factors of the meta-regression model [39]. We also conducted sensitivity analysis by dropping a small fraction of data to assess the robustness of meta-regression results [40], including the estimates from the moderate risk of bias studies, and the outliers identified by Cook’s distance. Factors for model selection were converted into dummy variables, factors, and their reference groups including study region (Western Pacific Region), VOC (Alpha), time since vaccination (14–90 days), vaccine brand (BBIBP-CorV), vaccine doses (primary series), age range (18–59 years old), population type (general), and study design (cohort study). Detailed factor groups can be found in Additional file 1: Tables S3 to S4.

Analyses were performed using the Meta-Analysis of Stata v17.0 and R software v4.2.2; the “metafor,” “dplyr,” “EnvStats,” and “ggplot2” packages were used for model selection, meta-regression, and visualization. A significance level of 5% was used for subsequent analysis.

Results

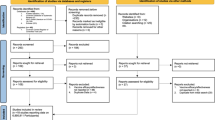

The initial search led to 2607 results. After deduplication and application of the eligibility criteria, 103 articles were included for full-text assessment. We discarded three redundant analyses of already-included studies; we discarded four randomized clinical trials and 45 other studies because they did not report outcomes related to vaccine effectiveness or did not provide relevant data to determine outcomes. In addition, two negative VE estimates were discarded due to study bias. Ultimately, 51 eligible studies with 151 estimates were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Figure 1 shows the study selection flow diagram.

Study characteristics and quality assessment

Additional file 1: Table S5 shows the detailed characteristics of the 51 included studies [41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91], and Additional file 1: Tables S3 to S4 and S6 show the summary of the key characteristics of the included studies and VE evaluations. The total study population was 142,236,816 subjects. Among included studies, 60.78% (31/51) only used the RT-PCR test as the infection identification method, while 35.29% (18/51) used both RT-PCR and antigen test to identify infection, and 2 studies did not specify the identification method of confirmed infection cases. We extracted 151 VE evaluations, among which 65 were evaluations against SARS-CoV-2 infection and 86 were against severe COVID-19.

The quality assessment showed that the risk of bias in most of the studies (48 studies) was low. The other three studies had a moderate risk of bias. Additional file 1: Tables S7 to S9 shows the quality assessment results.

Primary series vaccine effectiveness

Meta-analysis of 44 evaluations of primary series VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection and 57 evaluations of primary series VE against severe COVID-19 during Alpha, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron periods showed that VE against infection varied by VOC and time since vaccination and that VE against severe COVID-19 was higher than against infection and always greater than 60% against each variant (Tables 1 and 2).

The pooled estimate of VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection was higher against Delta (52.8% [95% CI, 43.3 to 60.7%]) and Gamma (44.2% [95% CI, 39.4 to 48.6%]) than against Omicron (16.4% [95% CI, 9.5 to 22.8%]). VE 14–90 days after vaccination was 87.0% (95% CI, 86.0 to 88.0%) against Alpha; 46.2% (95% CI, 38.4 to 53.0%) against Gamma, remaining stable during 90–180 days (42.1% [95% CI, 37.3 to 46.5%]); 56.3% (95% CI, 38.2 to 69.1%) against Delta, decreasing to 22.2% (95% CI, 4.9 to 36.3%) and 20.9% (95% CI, 8.1 to 31.9%) beyond 90 and 180 days respectively; and 34.1% (95% CI, 24.0 to 42.8%) against Omicron, decreasing to 7.2% (95% CI, 2.3 to 11.7%) after 180 days.

The pooled estimate of VE against severe COVID-19 was 84.0% (95% CI, 57.0 to 94.1%) against Alpha, similar to VEs against Gamma (73.3% [95% CI, 64.7 to 79.8%]), Delta (69.4, [95% CI, 63.1 to 74.6%]), and Omicron (66.0% [95% CI, 61.4 to 70.1%]). VE against severe COVID-19 14–90 days after vaccination was 90.0% (95% CI, 88.3 to 91.5%) against Alpha; 77.5% (95% CI, 56.1 to 88.5%) against Gamma, remaining stable during 90–180 days after vaccination (77.0% [95% CI, 74.7 to 79.1%]); 78.7% (95% CI, 59.6 to 88.8%) against Delta, 56.2% (95% CI, 40.0 to 68.0%) and 56.8% (95% CI, 35.7 to 71.0%) beyond 90 and 180 days respectively; 59.9% (95% CI, 46.1 to 70.1%) for Omicron, remaining stable after 180 days post-vaccination (64.5% [95% CI, 55.2 to 71.9%]). More detailed results of the subgroup analysis are shown in Additional file 1: Tables S10 to S12.

Booster dose vaccine effectiveness

Nine evaluations of booster dose VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection showed that VE was 65.2% (95% CI, 48.3 to 76.6%) against Delta, similar to the primary series VE against Delta in 14–90 days. Booster dose VE decreased to 20.3% (95% CI, 10.5 to 28.0%) against Omicron, similar to the primary series VE against Omicron in 14–90 days.

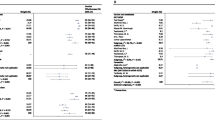

In 14 evaluations of booster dose VE against severe COVID-19, VE was 79.2% (95% CI, 71.7 to 84.7%) against Delta and 87.3% (95% CI, 77.8 to 92.7%) against Omicron, and booster dose was more effective than primary vaccination against Omicron variant (Table 3). Due to the later starting time of booster vaccination, no VE estimates more distant than 14 to 90 days after booster vaccination could be determined. Comparison of primary series and booster doses VE against different VOC and time since vaccination is shown in Fig. 2.

Duration of vaccine effectiveness against each variant of concern. Points with error bars are VEs and 95% CIs of primary series and booster doses against different VOC and time since vaccination. “VOC_Time” includes days since the last dose vaccination during each variant of concern, “ − 90” means 14–90 days, “ − 180” means 91–180 days, and “ − 180 + ” means ≥ 180 days. Dotted lines were the LOESS smoothing curves, indicating VE variation tendency. Effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines for the primary series against SARS-CoV-2 infection waned over time since vaccination and VOC and was restored by booster doses during Delta and Omicron periods; effectiveness against severe COVID-19 was much greater compared to the effectiveness against infection, improved when boosted during Delta and Omicron periods

Meta-regression analysis

For VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection, the lowest AICc value of potential models was 118.462; we selected eight top potential best models based on the ΔAICc among 28 possible models (Table 4). After comparing the R2 values of potential best models, we found that model 6 was the best model with the highest R2 of 33.4%, and its ΔAICc was 3.451 compared to the lowest AICc (model 1). Variables in the best model were “study region,” “VOC,” and “time since vaccination,” and meta-regression results showed that each of these variables had a statistically significant association with vaccine effectiveness (Table 5). VE against Omicron variant was significantly different from VE against Alpha, and the risk of infection after vaccination during Omicron predominant period was 2.963 times compared with Alpha (the exponentiation of correlation coefficient exp(b) = 2.963, P = 0.021) after controlling for study region and time since vaccination. Risk of infection based on time since vaccination was not significantly different 90–180 days since vaccination (P = 0.067) compared to 14–90 days but was 1.772 times higher when the time since vaccination was greater than 180 days (exp(b) = 1.772, P = 0.022). Since vaccine doses were not the factor related to the change of VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection, and distance after booster vaccination for included studies could only be determined up to 90 days, meta-regression results also showed that booster doses restored VE to that seen 14 to 90 days after the primary series. VE against infection in the Eastern Mediterranean region was significantly different (exp(b) = 0.437, P = 0.014) from Western Pacific Region.

For VE against severe COVID-19, the lowest AICc value was 169.355 among 28 possible models; we selected three top potential best models based on the ΔAICc (Table 6). Model 1 was the best model with the highest R2 of 56.9% and the lowest AICc. Variables in the best model were “vaccine doses,” “age range,” “study design,” “study region,” “population type,” and “VOC,” and they all had a statistically significant association with VE against severe COVID-19 (Table 7). After controlling for other explanatory variables, the risk of severe COVID-19 after the booster dose was decreased (exp(b) = 0.541, P = 0.001) compared with the primary series. Compared with Alpha, risks of severe COVID-19 after vaccination during Gamma (exp(b) = 2.195, P = 0.034), Delta (exp(b) = 2.672, P = 0.001), and Omicron (exp(b) = 3.121, P = 0.001) were higher. VE against severe COVID-19 in Western Pacific Region was significantly different from the region of the Americas (exp(b) = 1.589, P = 0.034) and the European region (exp(b) = 2.587, P < 0.001).

Publication bias and sensitivity analysis

Based on visual inspection of the funnel plot (Additional file 1: Figs. S1 to S2), and the results of Egger’s test for small-study effect, we found asymmetry for VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection (P < 0.001) and severe COVID-19 (P = 0.008). However, the results of Begg’s test for small-study effect showed no significant publication bias against SARS-CoV-2 infection (P = 0.865) or severe COVID-19 (P = 0.351). The results did not change after a trim and fill test, indicating that the impact of bias was likely not significant.

After sensitivity analysis (Additional file 1: Tables S13 to S16), meta-regression results did not change except for the model of VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection, factor “study region” related to the VE before it became insignificant after deleting the moderate risk of bias estimate, but results of other factors did not overturn or reverse, indicating the overall robustness of our meta-regression results.

Discussion

This comprehensive systematic review and meta-regression of the effectiveness and associated factors of two globally prominent inactivated vaccines (CoronaVac and BBIBP-CorV) included 151 VE estimates in 51 studies conducted over multiple countries and included a combined total of more than 140 million subjects. Quality assessment and publication bias testing showed relatively high reliability of meta-analysis results. The two negative VE estimates against COVID-19 infection that we excluded have study bias shown in the articles, one is due to health-seeking bias in low- and middle-income populations that would increase the frequency of disease among vaccinated [75], and the other one is due to the generally more active and higher rate of social contact and frequent hospital or hemodialysis center visits for vaccinated younger patients with chronic kidney disease [89]. R2 values in meta-regression were above 30% for regressions on VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection and 50% against severe COVID-19, suggesting that the variables included in the regression model that were possible to extract from articles provided a relatively high degree of explanation of VE heterogeneity. We found that VE against COVID-19 did not vary by vaccine brand, but varied by study region and VOC. Time since vaccination associated with VE against infection specifically, while vaccine doses, age, study design, and study population type associated with VE against severe outcomes specifically.

Changes in VE against variants were observed in the meta-analysis, but for primary series VE against infection during Alpha variant predominant period, we got the opposite result (VE = 72.0%, 95% CI, − 27.3 to 93.8%) after merging two studies which both concluded that VE against Alpha had positive effectiveness. This was due to the use of a randomized effect model [92] to account for the high heterogeneity (P < 0.001, I2 = 99.11%) from much better VE in Petrović’s study [76] compared to Can’s [55]. In our opinion, inactivated vaccines should still have positive and high effectiveness against Alpha, since the risk of bias in two studies was low, and we found that VE was significantly decreased against Omicron compared to Alpha against SARS-CoV-2 infection in meta-regression analysis. We confirmed that VOC related to the decrease of VE, especially during the Omicron variant-predominant period against infection and severe COVID-19, and Gamma and Delta variants also related to the decrease of VE against severe COVID-19 compared to Alpha variant. These findings are consistent with recent studies showing that inactivated VE was significantly lower against some variants, especially Omicron [12, 93,94,95,96], which may be related to immune escape when comparing immunogenicity against the ancestral strain of the virus [97,98,99].

The risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection rose when the time since vaccination was longer than 6 months, 1.772 times that of the 14–90-day risk of infection, consistent with immunological data showing decreased antibody levels over time for different types of vaccines [95, 100,101,102]. However, meta-regression showed no significant difference in VE against severe COVID-19 for more than 6 months. This finding reflects longer-lasting protection provided by inactivated vaccines against severe COVID-19 compared to protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection and is similar to previous studies and meta-analysis [12, 103, 104].

VE of booster dose significantly increased compared to primary vaccination against severe COVID-19, but booster dose VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection did not change significantly compared to primary series VE when adjusting for factors such as time since vaccination. This indicates that booster doses restored effectiveness to that seen shortly after completion of the primary series (and before primary series VE waned). A caveat is that booster dose VE duration was only evaluated for a limited time, up to 90 days could be determined. Our finding is consistent with evidence from an immune response study showing that inactivated vaccine booster doses enhanced seroconversion and neutralizing capability against Delta and Omicron [105], reinforcing the necessity of booster doses 6 months after primary series vaccination.

Regional differences in VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 are likely related to variations in prevention and control strategies, vaccination policies, and force of infection in different countries. Vaccination is an important component of the pandemic response, but vaccination alone is an incomplete response to COVID-19; public health and social measures are necessary to continue building population immunity with SARS-CoV-2 vaccines [106].

Our findings have important policy implications for SARS-CoV-2 vaccination. Inactivated vaccines have strong, sustained protection from severe COVID-19 in our meta-analysis, more than 180 days after the primary series, and VE against severe COVID-19 during Omicron predominant period was 66.0% for the primary series and 87.3% for a booster dose in the real-world studies, supporting the continued use of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines to prevent severe COVID-19. In particular, countries should keep promoting booster dose vaccination, which can restore effectiveness to that seen shortly after the completion of the primary series against SARS-CoV-2 infection, and related to the greater VE compared to the primary series against severe COVID-19. Additionally, attention should be given to the time after vaccination since primary series VE waned after 6 months against infection, and continued surveillance of booster dose VE with time is needed.

Our study has limitations. The definition of infection varies by country and region, and some studies included asymptomatic, infected individuals in the study population, which may lead to an underestimation of vaccine effectiveness. Factors such as vaccination coverage level and COVID-19 prevention and control measures may be associated with SARS-CoV-2 exposure; this information was difficult to extract from the included articles. We included study region in the meta-regression, which may alleviate the influence of control-measure variation, but it cannot eliminate related bias, and it appears to be susceptible to the change of sample due to the variation in the number of included studies across countries, as what we observed in the sensitivity analysis. Although we attempted to determine accurately the predominate VOC in the studies, the mutation of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is a gradual process, some of which included unknown mixtures of other variants and were not possible to separate. In addition, though we discarded redundant studies, it is still possible that there are similar populations among included studies, so the combined total of subjects in our included studies might be slightly lower than the number we counted.

Conclusions

Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines were found to have moderate primary series VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection that wanes over 6 months but is restored by booster doses. Inactivated primary series VE against severe COVID-19 (hospitalization or worse) was much greater than VE against infection and sustained for more than 6 months and was highest when boosted. VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection and severe COVID-19 varied by variant, most notably waned against Omicron. These findings demonstrate optimal protection from severe COVID-19 requires booster doses, and it is important to continue monitoring the evolution of the virus and the effectiveness of the vaccines against new variants and to accelerate vaccine development to produce vaccines capable of blocking infection and preventing severe COVID-19 against a wider range of coronaviruses, either variant-specific vaccines or pan-sarbecovirus vaccines. It is also necessary to monitor the severity of breakthrough infections to ensure that vaccine protection from severe COVID-19 remains robust.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Abbreviations

- AHRQ:

-

Agency for healthcare research and quality

- AIC:

-

Akaike’s information criterion

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- IgM:

-

Immunoglobulin M

- MOOSE:

-

Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology

- NPI:

-

Non-pharmaceutical intervention

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- RR:

-

Rate ratio

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction

- VE:

-

Vaccine effectiveness

- VOC:

-

Variant of concern

- WHO:

-

World health organization

- WT:

-

Wild‐type

References

Khan WH, Hashmi Z, Goel A, Ahmad R, Gupta K, Khan N, et al. COVID-19 pandemic and vaccines update on challenges and resolutions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:690621.

World Health Organization. Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. 2022. https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants. Accessed 12 Oct 2022.

Barranco R, Rocca G, Molinelli A, Ventura F. Controversies and challenges of mass vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 in Italy: medico-legal perspectives and considerations. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1163.

World Health Organization. Status of COVID-19 vaccines within WHO EUL/PQ evaluation process. 2022. https://extranet.who.int/pqweb/sites/default/files/documents/Status_COVID_VAX_21September2022.pdf. Accessed 21 Sep 2022.

Hadj HI. COVID-19 vaccines and variants of concern: a review. Rev Med Virol. 2022;32:e2313.

World Health Organization. The Sinovac-CoronaVac COVID-19 vaccine: what you need to know. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-sinovac-covid-19-vaccine-what-you-need-to-know. Accessed 22 Feb 2023.

World Health Organization. The Sinopharm COVID-19 vaccine: what you need to know. 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/the-sinopharm-covid-19-vaccine-what-you-need-to-know. Accessed 22 Feb 2023.

Zar HJ, MacGinty R, Workman L, Botha M, Johnson M, Hunt A, et al. Natural and hybrid immunity following four COVID-19 waves: a prospective cohort study of mothers in South Africa. EClinicalMedicine. 2022;53:101655.

Fan YJ, Chan KH, Hung IF. Safety and efficacy of COVID-19 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis of different vaccines at phase 3. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:989.

Souza WM, Amorim MR, Sesti-Costa R, Coimbra LD, Brunetti NS, Toledo-Teixeira DA, et al. Neutralisation of SARS-CoV-2 lineage P.1 by antibodies elicited through natural SARS-CoV-2 infection or vaccination with an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: an immunological study. Lancet Microbe. 2021;2:e527-35.

Zheng C, Shao W, Chen X, Zhang B, Wang G, Zhang W. Real-world effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines: a literature review and meta-analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;114:252–60.

Liu Q, Qin C, Liu M, Liu J. Effectiveness and safety of SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in real-world studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10:132.

Dadras O, SeyedAlinaghi S, Karimi A, Shojaei A, Amiri A, Mahdiabadi S, et al. COVID-19 vaccines’ protection over time and the need for booster doses; a systematic review. Arch Acad Emerg Med. 2022;10:e53.

Fu Y, Zhao J, Wei X, Han P, Yang L, Ren T, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of inactivated vaccine to address COVID-19 pandemic in China: evidence from randomized control trials and real-world studies. Front Public Health. 2022;10:917732.

Chemaitelly H, Tang P, Hasan MR, AlMukdad S, Yassine HM, Benslimane FM, et al. Waning of BNT162b2 vaccine protection against SARS-CoV-2 infection in Qatar. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:e83.

Fiolet T, Kherabi Y, MacDonald CJ, Ghosn J, Peiffer-Smadja N. Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28:202–21.

Balkan İ, Dinc HO, Can G, Karaali R, Ozbey D, Caglar B, et al. Waning immunity to inactive SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthcare workers: booster required. Ir J Med Sci. 2023;192:19–25.

Ge Y, Zhang WB, Wu X, Ruktanonchai CW, Liu H, Wang J, et al. Untangling the changing impact of non-pharmaceutical interventions and vaccination on European COVID-19 trajectories. Nat Commun. 2022;13:3106.

Pormohammad A, Zarei M, Ghorbani S, Mohammadi M, Aghayari Sheikh Neshin S, Khatami A, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against Delta (B.1.617.2) variant: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical studies. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;10:23.

Zeng B, Gao L, Zhou Q, Yu K, Sun F. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2022;20:200.

Shao W, Chen X, Zheng C, Liu H, Wang G, Zhang B, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 variants of concern in real-world: a literature review and meta-analysis. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11:2383–92.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis Of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283:2008–12.

International Vaccine Access Center. Results of COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness & impact studies: an ongoing systematic review, methods. https://view-hub.org/covid-19/effectiveness-studies. Accessed 8 Oct 2022.

World Health Organization. WHO COVID-19 case definition. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Surveillance_Case_Definition-2022.1. Accessed 22 Jul 2022.

World Health Organization. Living guidance for clinical management of COVID-19. 2021. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-clinical-2021-2. Accessed 23 Aug 2022.

Chen X, Chen Z, Azman AS, Sun R, Lu W, Zheng N, et al. Neutralizing antibodies against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) variants induced by natural infection or vaccination: a systematic review and pooled analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2022;74:734–42.

Zeng X, Zhang Y, Kwong JS, Zhang C, Li S, Sun F, et al. The methodological quality assessment tools for preclinical and clinical studies, systematic review and meta-analysis, and clinical practice guideline: a systematic review. J Evid Based Med. 2015;8:2–10.

Movahedian M, Golzan SA, Ashtary-Larky D, Clark CCT, Asbaghi O, Hekmatdoost A. The effects of artificial- and stevia-based sweeteners on lipid profile in adults: a GRADE-assessed systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression of randomized clinical trials. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2021.2012641.

Sekizawa Y, Konishi Y, Kimura M. Are the effects of blood pressure lowering treatment diminishing?: meta-regression analyses. Clin Hypertens. 2018;24:16.

Begg CB, Mazumdar M. Operating characteristics of a rank correlation test for publication bias. Biometrics. 1994;50:1088–101.

Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–34.

Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–63.

Thompson SG, Sharp SJ. Explaining heterogeneity in meta-analysis: a comparison of methods. Stat Med. 1999;18:2693–708.

Tanriver-Ayder E, Faes C, van de Casteele T, McCann SK, Macleod MR. Comparison of commonly used methods in random effects meta-analysis: application to preclinical data in drug discovery research. BMJ Open Sci. 2021;5:e100074.

Whittingham MJ, Stephens PA, Bradbury RB, Freckleton RP. Why do we still use stepwise modelling in ecology and behaviour? J Anim Ecol. 2006;75:1182–9.

Cinar O, Umbanhowar J, Hoeksema JD, Viechtbauer W. Using information-theoretic approaches for model selection in meta-analysis. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12:537–56.

Anderson DR. Model based inference in the life sciences: a primer on evidence. New York: Springer; 2008.

Bolker BM. Ecological models and data in R: Princeton University Press; 2008.

Harrer M, Cuijpers P, Furukawa T, Ebert D. Doing meta-analysis with R: a hands-on guide. New York: Chapman and Hall/CRC; 2021.

Broderick T, Giordano R, Meager R. An automatic finite-sample robustness metric: can dropping a little data change conclusions? arXiv.org. 2021;https://arxiv.org/abs/2011.14999.

Arregoces. L, Fernández. J, Rojas-Botero. M, Palacios-Clavijo. A, M. Galvis LER, Pinto-Álvarez. M, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in preventing hospitalizations and deaths in colombia: a pair-matched, national-wide cohort study in older adults. SSRN. 2021; http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3944059.

Hitchings MDT, Ranzani OT, Torres MSS, de Oliveira SB, Almiron M, Said R, et al. Effectiveness of CoronaVac among healthcare workers in the setting of high SARS-CoV-2 Gamma variant transmission in Manaus, Brazil: a test-negative case-control study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2021;1:100025.

Jara A, Undurraga EA, González C, Paredes F, Fontecilla T, Jara G, et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in Chile. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:875–84.

Ranzani OT, Hitchings MDT, Dorion M, D’Agostini TL, de Paula RC, de Paula OFP, et al. Effectiveness of the CoronaVac vaccine in older adults during a gamma variant associated epidemic of covid-19 in Brazil: test negative case-control study. BMJ. 2021;374:n2015.

Suah JL, Tok PSK, Ong SM, Husin M, Tng BH, Sivasampu S, et al. PICK-ing Malaysia’s epidemic apart: effectiveness of a diverse COVID-19 vaccine portfolio. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9:1381.

Pacheco AG, Cruz OG, Carvalho LM, Codeço CT, Costa Gomes MFd, Coelho FC, et al. Effectiveness of mass vaccination in Brazil against severe COVID-19 cases. medRxiv. 2021;https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.09.10.21263084.

Al Kaabi N, Oulhaj A, Ganesan S, Al Hosani FI, Najim O, Ibrahim H, et al. Effectiveness of BBIBP-CorV vaccine against severe outcomes of COVID-19 in Abu Dhabi United Arab Emirates. Nat Commun. 2022;13:3215.

Arregocés-Castillo L, Fernández-Niño J, Rojas-Botero M, Palacios-Clavijo A, Galvis-Pedraza M, Rincón-Medrano L, et al. Effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in older adults in Colombia: a retrospective, population-based study of the ESPERANZA cohort. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2022;3:e242–52.

Arriola C, Soto G, Westercamp M, Bollinger S, Espinoza A, Grogl M, et al. Effectiveness of whole-virus COVID-19 vaccine among healthcare personnel, Lima. Peru Emerg Infect Dis. 2022;28:S238–43.

Ashmawy. R, Kamal. E, Sharaf. S, Elsaka. N, Esmail. OF, Kabeel. S, et al. Effectiveness and safety of inactivated SARS-CoV2 vaccine (BBIBP-CorV) among healthcare workers: a seven-month follow-up study at fifteen hospitals. Research Square. 2022;https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-1431715/v1.

Aslam J, Rauf UI Hassan M, Fatima Q, Bashir Hashmi H, Alshahrani MY, Alkhathami AG, et al. Association of disease severity and death outcome with vaccination status of admitted COVID-19 patients in delta period of SARS-COV-2 in mixed variety of vaccine background. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2022;29:103329.

Bayhan GI, Guner R. Effectiveness of CoronaVac in preventing COVID-19 in healthcare workers. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2022;18:2020017.

Belayachi J, Obtel M, Mhayi A, Razine R, Abouqal R. Long term effectiveness of inactivated vaccine BBIBP-CorV (Vero Cells) against COVID-19 associated severe and critical hospitalization in Morocco. PLoS One. 2022;17:e0278546.

Rivas AL, van Regenmortel MHV. COVID-19 related interdisciplinary methods: preventing errors and detecting research opportunities. Methods. 2021;195:3–14.

Can G, Acar HC, Aydin SN, Balkan II, Karaali R, Budak B, et al. Waning effectiveness of CoronaVac in real life: a retrospective cohort study in health care workers. Vaccine. 2022;40:2574–9.

Cerqueira-Silva T, Andrews JR, Boaventura VS, Ranzani OT, de Araújo Oliveira V, Paixão ES, et al. Effectiveness of CoronaVac, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, BNT162b2, and Ad26.COV2.S among individuals with previous SARS-CoV-2 infection in Brazil: a test-negative, case-control study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:791–801.

Cerqueira-Silva T, de Araujo OV, Paixão ES, Florentino PTV, Penna GO, Pearce N, et al. Vaccination plus previous infection: protection during the omicron wave in Brazil. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:945–6.

Cerqueira-Silva T, de Araujo OV, Paixão ES, Júnior JB, Penna GO, Werneck GL, et al. Duration of protection of CoronaVac plus heterologous BNT162b2 booster in the Omicron period in Brazil. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4154.

Cerqueira-Silva T, Katikireddi SV, de Araujo OV, Flores-Ortiz R, Júnior JB, Paixão ES, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of heterologous CoronaVac plus BNT162b2 in Brazil. Nat Med. 2022;28:838–43.

González S, Olszevicki S, Gaiano A, Baino ANV, Regairaz L, Salazar M, et al. Effectiveness of BBIBP-CorV, BNT162b2 and mRNA-1273 vaccines against hospitalisations among children and adolescents during the Omicron outbreak in Argentina: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;13:100316.

Institute of Public Health. Evaluación de la efectividad de la vacuna contra la COVID-19 en Chile. 2021. https://www.paho.org/es/node/86651. Accessed 20 Aug 2022.

Hu Z, Tao B, Li Z, Song Y, Yi C, Li J, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines against severe illness in B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant-infected patients in Jiangsu, China. China Int J Infect Dis. 2022;116:204–9.

Jara. A, Undurraga. E, Flores. JC, Zubizarreta. J, González. C, Pizarro. A, et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in children and adolescents: a large-scale observational study. SSRN. 2022; http://dx.doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4035405.

Jara A, Undurraga EA, Zubizarreta JR, González C, Acevedo J, Pizarro A, et al. Effectiveness of CoronaVac in children 3–5 years of age during the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron outbreak in Chile. Nat Med. 2022;28:1377–80.

Jara A, Undurraga EA, Zubizarreta JR, González C, Pizarro A, Acevedo J, et al. Effectiveness of homologous and heterologous booster doses for an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine: a large-scale prospective cohort study. Lancet Glob Health. 2022;10:e798-806.

Ma C, Sun W, Tang T, Jia M, Liu Y, Wan Y, et al. Effectiveness of adenovirus type 5 vectored and inactivated COVID-19 vaccines against symptomatic COVID-19, COVID-19 pneumonia, and severe COVID-19 caused by the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant: evidence from an outbreak in Yunnan, China, 2021. Vaccine. 2022;40:2869–74.

Marra AR, Miraglia JL, Malheiros DT, Guozhang Y, Teich VD, da Silva VE, et al. Effectiveness of two coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vaccines (viral vector and inactivated viral vaccine) against severe acute respiratory coronavirus virus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection in a cohort of healthcare workers. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2023;44:75–81.

McMenamin ME, Nealon J, Lin Y, Wong JY, Cheung JK, Lau EHY, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of one, two, and three doses of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac against COVID-19 in Hong Kong: a population-based observational study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:1435–43.

Mirahmadizadeh A, Heiran A, Bagheri Lankarani K, Serati M, Habibi M, Eilami O, et al. Effectiveness of coronavirus disease 2019 vaccines in preventing infection, hospital admission, and death: a historical cohort study using Iranian registration data during vaccination program. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2022;9:ofac177.

Mousa M, Albreiki M, Alshehhi F, AlShamsi S, Marzouqi NA, Alawadi T, et al. Similar effectiveness of the inactivated vaccine BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) and the mRNA vaccine BNT162b2 (Pfizer-BioNTech) against COVID-19 related hospitalizations during the Delta outbreak in the UAE. J Travel Med. 2022;29:taac036.

Nukenova G, Yesmagambetova A, Singer D, Henderson A, Tsoy A. Effectiveness of four vaccines in preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection in Kazakhstan. medRxiv. 2022;https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.04.14.22273868.

Nadeem I, Ul Munamm SA, Ur Rasool M, Fatimah M, Abu Bakar M, Rana ZK, et al. Safety and efficacy of Sinopharm vaccine (BBIBP-CorV) in elderly population of Faisalabad district of Pakistan. Postgrad Med J. 2022:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/postgradmedj-2022-141649.

Vokó Z, Kiss Z, Surján G, Surján O, Barcza Z, Wittmann I, et al. Effectiveness and waning of protection with different SARS-CoV-2 primary and booster vaccines during the Delta pandemic wave in 2021 in Hungary (HUN-VE 3 Study). Front Immunol. 2022;13:919408.

Paixao ES, Wong KLM, Alves FJO, de Araújo OV, Cerqueira-Silva T, Júnior JB, et al. CoronaVac vaccine is effective in preventing symptomatic and severe COVID-19 in pregnant women in Brazil: a test-negative case-control study. BMC Med. 2022;20:146.

Paternina-Caicedo A, Jit M, Alvis-Guzmán N, Fernández JC, Hernández J, Paz-Wilches JJ, et al. Effectiveness of CoronaVac and BNT162b2 COVID-19 mass vaccination in Colombia: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Am. 2022;12:100296.

Petrović V, Vuković V, Marković M, Ristić M. Early effectiveness of four SARS-CoV-2 vaccines in preventing COVID-19 among adults aged ≥60 years in Vojvodina, Serbia. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:389.

Ranzani OT, Hitchings MDT, de Melo RL, de França GVA, Fernandes CFR, Lind ML, et al. Effectiveness of an inactivated COVID-19 vaccine with homologous and heterologous boosters against Omicron in Brazil. Nat Commun. 2022;13:5536.

Rearte A, Castelli JM, Rearte R, Fuentes N, Pennini V, Pesce M, et al. Effectiveness of rAd26-rAd5, ChAdOx1 nCoV-19, and BBIBP-CorV vaccines for risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 and death due to COVID-19 in people older than 60 years in Argentina: a test-negative, case-control, and retrospective longitudinal study. Lancet. 2022;399:1254–64.

Sritipsukho P, Khawcharoenporn T, Siribumrungwong B, Damronglerd P, Suwantarat N, Satdhabudha A, et al. Comparing real-life effectiveness of various COVID-19 vaccine regimens during the delta variant-dominant pandemic: a test-negative case-control study. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11:585–92.

Suah JL, Husin M, Tok PSK, Tng BH, Thevananthan T, Low EV, et al. Waning COVID-19 vaccine effectiveness for BNT162b2 and CoronaVac in Malaysia: an observational study. Int J Infect Dis. 2022;119:69–76.

Suphanchaimat R, Nittayasoot N, Jiraphongsa C, Thammawijaya P, Bumrungwong P, Tulyathan A, et al. Real-world effectiveness of mix-and-match vaccine regimens against SARS-CoV-2 Delta variant in Thailand: a nationwide test-negative matched case-control study. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:1080.

Hermawan A, Ramadhany R, Indalao IL, Agustiningsih A, Fikriyah EH, Tobing KL, et al. Real world performance of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine (CoronaVac) against infection, hospitalization and death due to COVID-19 in adult population in Indonesia. medRxiv. 2022;https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.02.02.22270351.

Toker İ, Kılınç Toker A, Turunç Özdemir A, Çelik İ, Bol O, Bülbül E. Vaccination status among patients with the need for emergency hospitalizations related to COVID-19. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;54:102–6.

Torres R, Toro L, Sanhueza ME, Lorca E, Ortiz M, Pefaur J, et al. Clinical efficacy of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int Rep. 2022;7:2176–85.

Wu D, Zhang Y, Tang L, Wang F, Ye Y, Ma C, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines against symptomatic, pneumonia, and severe disease caused by the Delta variant: real world study and evidence - China, 2021. China CDC Wkly. 2022;4:57–65.

Zhang Y, Belayachi J, Yang Y, Fu Q, Rodewald L, Li H, et al. Real-world study of the effectiveness of BBIBP-CorV (Sinopharm) COVID-19 vaccine in the Kingdom of Morocco. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1584.

Florentino PTV, Alves FJO, Cerqueira-Silva T, Oliveira VA, Júnior JBS, Jantsch AG, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of CoronaVac against COVID-19 among children in Brazil during the Omicron period. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4756.

Yan VKC, Wan EYF, Ye X, Mok AHY, Lai FTT, Chui CSL, et al. Effectiveness of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac vaccinations against mortality and severe complications after SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 infection: a case-control study. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11:2304–14.

Cheng FWT, Fan M, Wong CKH, Chui CSL, Lai FTT, Li X, et al. The effectiveness and safety of mRNA (BNT162b2) and inactivated (CoronaVac) COVID-19 vaccines among individuals with chronic kidney diseases. Kidney Int. 2022;102:922–5.

Wan EYF, Mok AHY, Yan VKC, Wang B, Zhang R, Hong SN, et al. Vaccine effectiveness of BNT162b2 and CoronaVac against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2 infection, hospitalisation, severe complications, cardiovascular disease and mortality in patients with diabetes mellitus: a case control study. J Infect. 2022;85:e140-4.

Kang M, Yi Y, Li Y, Sun L, Deng A, Hu T, et al. Effectiveness of inactivated COVID-19 vaccines against illness caused by the B.1.617.2 (Delta) variant during an outbreak in Guangdong, China: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:533–40.

Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. A basic introduction to fixed-effect and random-effects models for meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods. 2010;1:97–111.

Buathong R, Hunsawong T, Wacharapluesadee S, Guharat S, Jirapipatt R, Ninwattana S, et al. Homologous or heterologous COVID-19 booster regimens significantly impact sero-neutralization of SARS-CoV-2 virus and its variants. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:1321.

Zou L, Zhang H, Zheng Z, Jiang Y, Huang Y, Lin S, et al. Serosurvey in SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine-elicited neutralizing antibodies against authentic SARS-CoV-2 and its viral variants. J Med Virol. 2022;94:6065–72.

Dolgin E. COVID vaccine immunity is waning - how much does that matter? Nature. 2021;597:606–7.

Uriu K, Kimura I, Shirakawa K, Takaori-Kondo A, Nakada TA, Kaneda A, et al. Neutralization of the SARS-CoV-2 Mu variant by convalescent and vaccine serum. N Engl J Med. 2021;385:2397–9.

Melo-González F, Soto JA, González LA, Fernández J, Duarte LF, Schultz BM, et al. Recognition of variants of concern by antibodies and T cells induced by a SARS-CoV-2 inactivated vaccine. Front Immunol. 2021;12:747830.

Duan LJ, Jiang WG, Wang ZY, Yao L, Zhu KL, Meng QC, et al. Neutralizing immunity against SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.1 by infection and vaccination. iScience. 2022;25:104886.

Hua Q, Zhang H, Yao P, Xu N, Sun Y, Lu H, et al. Immunogenicity and immune-persistence of the CoronaVac or Covilo inactivated COVID-19 vaccine: a 6-month population-based cohort study. Front Immunol. 2022;13:939311.

Hamady A, Lee J, Loboda ZA. Waning antibody responses in COVID-19: what can we learn from the analysis of other coronaviruses? Infection. 2022;50:11–25.

Kitabatake M, Ouji-Sageshima N, Sonobe S, Furukawa R, Konda M, Hara A, et al. Transition of antibody titers after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination in Japanese healthcare workers. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2023;76:72–6.

Naaber P, Tserel L, Kangro K, Sepp E, Jürjenson V, Adamson A, et al. Dynamics of antibody response to BNT162b2 vaccine after six months: a longitudinal prospective study. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;10:100208.

Khoury DS, Cromer D, Reynaldi A, Schlub TE, Wheatley AK, Juno JA, et al. Neutralizing antibody levels are highly predictive of immune protection from symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2021;27:1205–11.

Feikin DR, Higdon MM, Abu-Raddad LJ, Andrews N, Araos R, Goldberg Y, et al. Duration of effectiveness of vaccines against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease: results of a systematic review and meta-regression. Lancet. 2022;399:924–44.

Chen Y, Chen L, Yin S, Tao Y, Zhu L, Tong X, et al. The third dose of CoronVac vaccination induces broad and potent adaptive immune responses that recognize SARS-CoV-2 Delta and Omicron variants. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2022;11:1524–36.

World Health Organization. Updated WHO SAGE Roadmap for prioritizing uses of COVID-19 vaccines. 2022. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-2019-nCoV-Vaccines-SAGE-Prioritization-2022.1. Accessed 8 Sep 2022.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Lance Rodewald for the English language editing of the manuscript.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HW developed the idea for the study. SX and ZW designed the study. SX and JL conducted the database searches, article screening, and data extraction with the assistance of HW. SX performed the statistical analysis. ZY, HW, and FW verified the data. SX and JL wrote the first draft of the manuscript. ZW and ZY reviewed the subsequent drafts. All authors provided critical review and revision of the text and approved the final version. All authors had full access to all data and had joint responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. ZW and ZY had the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

MOOSE Checklist for Meta-analyses of Observational Studies. Table S2. Full search strategy for studies. Table S3. Characteristics of included studies. Table S4. Characteristics of VE evaluations. Table S5. Data extracted by included studies. Table S6. Population and SARS-CoV-2 infection Identification of included studies. Table S7. Quality assessment of cohort study. Table S8. Quality assessment of case-control study. Table S9. Quality assessment of descriptive study. Table S10. Subgroup analysis of primary series VE against VOC. Table S11. Subgroup analysis of primary series VE by time since vaccination. Table S12. Subgroup analysis of booster VE against VOC. Fig. S1. Funnel plot for VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Fig. S2. Funnel plot for VE against severe COVID-19. Table S13. Sensitivity analysis: meta-regression of VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Table S14. Sensitivity analysis: meta-regression of VE against severe COVID-19. Table S15. Sensitivity analysis: meta-regression of VE against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Table S16. Sensitivity analysis: meta-regression of VE against severe COVID-19.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, S., Li, J., Wang, H. et al. Real-world effectiveness and factors associated with effectiveness of inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccines: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. BMC Med 21, 160 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02861-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-023-02861-3