Abstract

Background

Non-medical issues (e.g. loneliness, financial concerns, housing problems) can shape how people feel physically and psychologically. This has been emphasised during the Covid-19 pandemic, especially for older people. Social prescribing is proposed as a means of addressing non-medical issues, which can include drawing on support offered by the cultural sector.

Method

A rapid realist review was conducted to explore how the cultural sector (in particular public/curated gardens, libraries and museums), as part of social prescribing, can support the holistic well-being of older people under conditions imposed by the pandemic. An initial programme theory was developed from our existing knowledge and discussions with cultural sector staff. It informed searches on databases and within the grey literature for relevant documents, which were screened against the review’s inclusion criteria. Data were extracted from these documents to develop context-mechanism-outcome configurations (CMOCs). We used the CMOCs to refine our initial programme theory.

Results

Data were extracted from 42 documents. CMOCs developed from these documents highlighted the importance of tailoring—shaping support available through the cultural sector to the needs and expectations of older people—through messaging, matching, monitoring and partnerships. Tailoring can help to secure benefits that older people may derive from engaging with a cultural offer—being distracted (absorbed in an activity) or psychologically held, making connections or transforming through self-growth. We explored the idea of tailoring in more detail by considering it in relation to Social Exchange Theory.

Conclusions

Tailoring cultural offers to the variety of conditions and circumstances encountered in later life, and to changes in social circumstances (e.g. a global pandemic), is central to social prescribing for older people involving the cultural sector. Adaptations should be directed towards achieving key benefits for older people who have reported feeling lonely, anxious and unwell during the pandemic and recovery from it.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

‘Non-medical’ issues affecting health and well-being, such as loneliness or lack of purpose, are matters of concern for older adults [1, 2]. Health problems associated with ageing can have a negative impact on confidence [3], bringing unique challenges in sustaining social relations for older people [4]. The Covid-19 pandemic amplified social isolation experienced by older people (who were identified as being at greater risk from complications of the virus if they contracted it) due to restrictions on in-person interaction [5, 6].

Social prescribing enables healthcare professionals to refer patients to community-based support and activities [7]. It is one way to address issues of well-being in later life during and beyond the Covid-19 pandemic. Social prescribing is an important mode of intervention in countries like the UK [8,9,10], the USA [11, 12], Australia [13] and Canada [14]. It relies on ‘link workers’ (they may be known by other titles, including ‘community connectors’ and ‘social prescribers’ [15]) who connect people to social or community-based services and activities that can help with their non-medical issues.

Part of the rationale for employing link workers is to improve patients’ holistic well-being and, by doing so, reduce demands on healthcare staff, particularly general practitioners [16]. In England, the NHS is funding link worker posts in primary care [17]; patients are often referred to a link worker by their general practitioner. Link workers have time to talk to a patient to find out what is of concern to them and what would help to improve their current situation. These employees should have a good knowledge of local services, organisations, charities and activities, which could help with a range of non-medical issues.

Among the range of community services that link workers might connect individuals to, cultural institutions (such as public gardens, libraries and museums) are promising for social prescribing [18, 19]. The closure of these venues during the pandemic reduced their capacity to support the community. However, the cultural sector has been resilient, setting up alternative means to reach people through digital and remote activities [20, 21].

We were funded to conduct a programme of research by the UK Research and Innovation (UKRI) Arts and Humanities Research Council; as part of this work we completed a rapid realist review. It aimed to understand how, for whom, in what ways and why the cultural sector, as part of social prescribing, can improve the well-being of older people (aged 60 years and above) in the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. We refer to ‘cultural offers’ below, meaning activities or spaces (online or in person) provided by a cultural organisation. This might include (but is not limited to) guided walks around a botanical garden, book groups run by a library or volunteering at a museum.

Methods

Realist reviews are an appropriate way of explaining how complex interventions (such as social prescribing) work, for whom, in what circumstances and why [22]. They are underpinned by a realist philosophy of science, which entails thinking about generative causation—the notion that outcomes are produced by mechanisms (often hidden), which may or may not be triggered depending on context [23]. Within a realist review, literature is drawn upon to develop explanations that focus on mechanisms that produce outcomes, and contexts required to trigger these mechanisms. It involves the development of context-mechanism-outcome configurations (CMOCs). CMOCs inform and are embedded within a programme theory—a proposition of how an intervention works, for whom, under what conditions and why [24].

We conducted a rapid realist review, defined as a “time responsive” approach to developing policy-sensitive recommendations on a topic [25]. A rapid, or restricted, approach has become popular across systematic review types; they are restricted in terms of truncating elements of the process [26]. In our review, this included using a limited number of databases to locate relevant papers (CINAHL, EMBASE, MEDLINE, Cochrane databases). We also sought to identify grey literature on the Repository for Arts and Health Resources (www.artshealthresources.org.uk) and were sent relevant documents by experts in the field.

Figure 1 shows the flow of references from screening to inclusion. Searching for and screening of documents ran between October 2020 and January 2021. Methods we used to identify papers and the review’s eligibility criteria have been published in a blog (https://socialprescribing.phc.ox.ac.uk/news-views/views/locating-data-sources-for-a-rapid-realist-review-on-the-cultural-sector-and-social-prescribing-for-older-people). We followed the RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards) reporting guidelines for realist reviews [27]. As it was a rapid review, we focused on identifying literature related to curated/public gardens, libraries and museums. However, feedback we received from a range of stakeholders whilst producing the review (see below) suggests that our findings relate to other cultural areas and activities.

We started the project by creating an initial programme theory in the form of a diagram, which we have published elsewhere [28]. Our team comprises expertise on social prescribing across disciplines and sectors, and this first iteration was based on our existing knowledge of social prescribing [19] and discussions with representatives from the cultural sector. It proposed how the cultural sector, through social prescribing, might work for older people, under what conditions. Through our engagement with the literature during the rapid realist review, we tested and refined the initial programme theory by considering how emerging CMOCs changed or extended our understanding of the topic.

In line with a realist logic, the analysis explored connections between context, mechanism and outcome to explain how cultural institutions (curated/public gardens, libraries and museums) might play a role in the well-being of older people as part of social prescribing, especially within the context of the Covid-19 pandemic. The qualitative computer programme NVIVO was used to organise data and identify key concepts; it has been noted as a useful tool for data management and analysis in a realist project [29]. Two reviewers (JG and SL) extracted data from included documents into broad concepts. They coded included literature within NVIVO, using this programme to help with clustering sections across documents that were on a similar topic. They initially coded based on broad terms (e.g. importance of space/place, sociability, cultural sector adaptability, patient expectations, link worker understanding). They used these broad concepts to think about CMOCs. They developed and shared their thinking with the rest of the research team in the form of written narratives. We also discussed emerging CMOCs with our project partners (representatives from the cultural sector and those involved in social prescribing) and our public involvement group (composed of older people) in the form of short presentations. Written notes were taken at these meetings. CMOCs were then amended based on this feedback.

Papers were assessed in terms of being ‘fit for purpose’ based on their ability to contribute to programme theory development [30]. This called for researchers to consider whether they contained useful data for extending or testing the emerging CMOCs and/or programme theory (‘relevance’) and examining, when necessary, whether the piece of data used was underpinned by credible and trustworthy methods (‘rigour’). We enhanced the rigour of our work through regular meetings with our project partners and our public involvement group. In February 2021, we also held three stakeholder meetings via Zoom, which were attended by older people, cultural sector staff and link workers (n=40 in total). At these meetings, we shared early findings from the review, which people discussed in small groups. CMOCs presented below came mainly from the reviewed literature but were augmented through conversations we had during these stakeholder meetings.

As is expected for this type of synthesis, we progressively focussed our realist review [27]. Our findings centre more on understanding the engagement of older people with cultural offers (i.e. the earlier parts of our initial programme theory). We judged this focus was important to understand initially because without engaging, any benefits from social prescribing for older people are not going to occur. Furthermore, the literature we found was mostly focussed on engagement.

Results

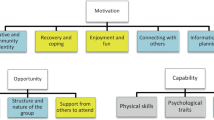

After screening 1033 references, data were extracted from 31 scientific articles and 11 reports [20, 21, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69,70] (details of included documents can be found in Additional file 1). Through our analysis, we created 18 CMOCs, which were used to refine our initial programme theory. These were discussed as a team and resulted in the development of a key concept included in the revised programme theory (see Fig. 2)—‘tailoring’. In broad terms, tailoring can be seen as the shaping of an intervention and its distribution to meet the needs of recipients (and providers) in a way that reflects the environment and circumstances in which it is delivered. In the review, tailoring relates to responses from link workers and cultural sector staff to older people’s needs, preferences and priorities, and to changing social situations (including a global pandemic). Tailoring underpins the pathway that enables older people to obtain benefits from a cultural offer as part of social prescribing, which we summarise in Fig. 2. These benefits can arise from the space in which the offer is provided (e.g. a building), from interactions involved or activities undertaken. In the rest of this section, we describe components of tailoring and the benefits that older people can receive from cultural offers.

Programme theory. Our rapid realist review highlighted how tailoring can help to ensure that an older person is receptive to the idea of engaging with a cultural offer. It also suggested some broad aspects of tailoring that cultural providers should consider when developing cultural offers (e.g. making sure people feel safe—physically and psychologically, that they can access offers—physically but also online, creating offers that are entertaining or absorbing, and providing a welcoming atmosphere, whether in-person or online). Through tailoring to optimise uptake of cultural offers and enjoyment/engagement with them, we propose that older people may experience one or more of the following benefits—being distracted from worries/concerns, feeling psychologically held, connecting with others, transforming their sense of self and place in the world

Components of tailoring

Through our engagement with the included evidence, and discussions with stakeholders, we identified and developed the following components of tailoring. The CMOCs that underpin and explain these components of tailoring are in Table 1.

Messaging—the means through which cultural offers as part of social prescribing are communicated (CMOCs 1–2)

Tailoring highlights how any offer proposed as part of social prescribing must be considered suitable by the recipient. Messaging applies to how someone is connected to a cultural offer as part of social prescribing (e.g. through seeing a link worker). Simply providing information may not be sufficient for such a suggestion to be adopted. Older people may want further details about what a cultural activity would entail [44]. Confidence is a common issue affecting older people’s participation in cultural activities [58, 63]. Hence, reassurance about the safety and welcoming nature of an offer is important [39, 44]. Our consultations with stakeholders emphasised that receiving adequate information plays a role in influencing expectations and decisions to join a cultural offer as part of social prescribing. Acceptance will be influenced by the value given to and recognition of the cultural sector’s role in supporting well-being. This may be shaped by how the idea of a cultural offer is presented to an older person (e.g. as a credible, positive opportunity).

Matching—having a good insight of what an older person might be open to trying and might benefit from, and having appropriate offers to connect them to (CMOCs 3–4)

The variety of requirements and expectations that people have in later life means that understanding and addressing an individual’s needs within social prescribing are key [48, 66]. This is a task for link workers to undertake. As part of tailoring, link workers discuss with an older person what they want/need, which may affect what they are directed towards. For tailoring to ensue, link workers must develop a relationship with an older person so they know what an individual expects. They need to identify who might be receptive to a cultural offer and consider how they propose this suggestion so it sounds like a viable source of support (see messaging above). They also need to be aware of what cultural offers are available locally [45]. Having a variety of activities is useful, to cater for a range of needs [67].

Monitoring—checking that cultural offers are acceptable and adapting them, when necessary, based on feedback and input from stakeholders (CMOCs 5–7)

Reviewed literature referred to the integration of evaluation and monitoring when developing interventions [55, 60]. Similarly, stakeholders stated that designing systems to receive feedback from older people and link workers creates cultural offers that are appropriate and address the needs of those involved in social prescribing. A solid monitoring and evaluation scheme may be necessary to demonstrate to funders the benefits that can transpire from cultural sector activities for social prescribing [55]. For link workers, keeping abreast of available cultural offers and checking with older people if they meet their needs is also important.

Partnerships—as social prescribing centres on human interaction (even when delivered remotely), positive relationships among different parties are required (CMOCs 8–10)

Partnerships are essential to identifying the diversity of circumstances, needs and expectations in later life, and tailoring an offer accordingly. Stakeholders reported that cultural institutions may need support and insight from other agencies to grasp the complex combination of characteristics and circumstances experienced by older people, and/or may not know how to reach individuals in need. Collaborations are important in this regard. The reviewed literature provided relevant examples of strategic collaborations with third sector organisations [49, 67], healthcare providers and clinicians [44, 45] and care homes [58]. Stakeholder feedback stated that communication between link workers and cultural sector staff creates an understanding of the contribution each can make to the well-being of older people. It means that link workers can advise on key information they need when proposing a cultural offer to older people. Interaction between cultural sector staff and older people ensures that offers are acceptable to and appropriate for the latter. Partnerships within a cultural organisation are also required; if an organisation is committed to supporting public well-being, and is open to some risk-taking, it will permit change and enable innovation to flourish. Outreach work may form part of this innovation [55]. Innovation has been required during Covid-19, when buildings were closed and cultural offers had to be delivered remotely (online but also by post or telephone). The importance of taking into account the well-being of cultural sector staff has been noted, as delivering these activities can be demanding; one way to address this is to have several staff working together [67].

Potential benefits for older people from a cultural offer

As we articulate in Fig. 2, it is through tailoring that benefits of cultural offers for older people can be realised. Some benefits may be quick to transpire but short lasting, others may be slower to emerge but more profound. For example, if an older person is seeking to escape from problems momentarily, then engaging with an exhibition online or in person may be appropriate. If they wish to make connections, they may need to attend several meetings or activities (in person or online).

Below, we explore the different benefits that can be derived from a cultural offer; the underpinning CMOCs are in Table 2.

Distracting—cultural offers can provide an immediate boost to people’s well-being (CMOCs 11–12)

Older people may welcome being distracted temporarily from worries by focusing on an offer and learning or trying something new [31, 32, 44, 63]. In the cultural sector, this can happen through stimulation, which can take a range of forms. For instance, handling objects can promote well-being through sensory engagement [39]. Similarly, online cultural offers can provide a multisensory experience by using 3D models of artworks that enable users to engage their imagination [42].

Offers can provide a break from daily routines, prompting people to do something different [36, 48, 58]. Having a consistent meeting time and location for a cultural offer may help with this [67], providing a structure to the week and giving people something to look forward to [48]. In terms of tailoring, link workers need to decipher how much structure an older person wants before referring them to a particular cultural offer.

Holding—cultural offers can afford people a sense of safety and belonging (CMOCs 13–14)

Cultural settings can be spaces where older people feel safe and included—in an ‘older person friendly’ environment. Professionalism and consistency of experience may be required for this to transpire. For example, knowing that staff will be warm and welcoming enables older people to relax and become immersed in a cultural offer [63]. When attending an offer for the first time, cultural sector staff can orient older people, to prevent them from feeling alone and to assuage any anxieties [58].

Efforts should be made to reduce stereotyping and stigmatisation in cultural settings [45], so that older people are treated respectfully as valued visitors [38, 44]. This includes providing adequate support for any physical or cognitive limitations, to prevent alienation. Co-production of cultural offers with older people may be important in this respect [55, 57].

Veall and colleagues [67] advised that cultural sector staff be mindful of a venue’s accessibility; awareness training around potential difficulties that older people may encounter when navigating a venue has been proposed, so that signs of distress are recognised and addressed [57]. Online offers can reduce the stress of traveling to a physical location [21]. Nevertheless, it is important to ensure that digital platforms are easy to navigate [21, 42, 65], and to assist people in their use, if necessary, so they maintain a sense of psychological safety or comfort.

Distress and discomfort can arise when a cultural offer is not suited to the needs and interests of older people. For instance, offers that involve lots of walking can be exhausting [62]. Viewing certain images or pieces of art could be unsettling and may unearth unpleasant memories [65, 67]; however, our consultations with stakeholders suggested this could be cathartic, if staff are available to help people manage how they feel. Offers that are tailored to the needs and interests of older people contribute to them feeling calm and welcomed [49].

Connecting—cultural offers can catalyse new social connections (CMOCs 15–16)

The literature identified making social connections as a vital element to cultural offers [36, 67, 68]. Participants in one article suggested socialisation should be a priority when designing an offer because they linked this to improved health and well-being [68]. This could be facilitated by having a shared point of focus within a cultural activity to promote dialogue between people who are strangers [40]. To make people feel at ease, having a facilitator experienced in knowing when and how to stimulate and moderate discussion is important [63].

Once the cultural offer ends, older people can maintain social connections by meeting on a more informal basis [62]; the cultural venue can act as a base to facilitate this [63]. Cultural offers enable older people to develop their communication skills by expanding the things they can discuss with others [63]. Yet not all cultural offers must contain a social element as not all older people will be seeking to make connections through social prescribing.

Online cultural offers may not necessarily replace face to face interactions [21] but they can provide an avenue for socialisation. They are a means of reaching a wider range of isolated/vulnerable people [42], although consideration is required to ensure the needs of individuals with sensory difficulties are addressed [20]. Online offers delivered through platforms with the capability for social interaction (e.g. Zoom) allow users to establish relationships, reducing isolation [21], with some research suggesting that as older people become accustomed to an online interface they enjoy it more as their confidence increases [42, 65]. To prevent fatigue from screen use, it is recommended that online sessions are kept short [21]. What is not clear is how short they should be; this is something that could be explored through co-producing cultural offers with older people.

Transforming—engaging with cultural offers can lead to self-growth and empowerment (CMOCs 17–18)

Engaging in the arts is associated with increased control and autonomy for older people [66]; cultural offers provide them with an opportunity to express themselves and to engage in pursuits that they perceive to be worthwhile [55]. Confidence, self-esteem and self-direction can be built [44, 66] by learning information or developing skills [32, 38], such as mastering how to use a digital application to access an online cultural offer [42, 65].

There was some evidence that connecting with others in a cultural setting can shape how older people see themselves. Todd and colleagues [63] reported that it enabled them to recognise their personal strengths, as they took steps to improve their situation by trying new things and then sharing their learning. This research also highlighted the positive reinforcement of self-worth and likability that older people received from communicating with peers at cultural settings.

Trying new things and receiving encouragement from staff and others can build self-confidence [63]. However, not all older people want to learn or try something new. Hence, outcomes for each person involved in social prescribing have to be tailored to their specific expectations and needs. Furthermore, although self-growth and transformation can transpire from engaging with a cultural offer, getting someone to accept an offer in the first place may be a problem due to a lack of self-confidence. This highlights the importance of tailoring through messaging, matching, monitoring and partnerships (see above) to encourage people to try something that may be unfamiliar.

Substantive theory: Social Exchange Theory

We considered the programme theory (Fig. 2) and associated CMOCs (Tables 1 and 2) in relation to substantive theories. As we wanted to further our understanding of tailoring and its potential impact on actors (older people, link workers, cultural sector staff), we were most interested in theory that would help us to do this. Social Exchange Theory was regarded as appropriate in this regard.

Homans [71] described human interactions in terms of costs, rewards and reinforcement—core concepts of Social Exchange Theory. What is exchanged in a social interaction might not be explicit. Social rewards can be intrinsic (e.g. feeling valued, respected, understood) or extrinsic (e.g. goods, services). Costs vary and include (but are not limited to) time, energy and money. When someone regards a social exchange as inequitable, frustration can ensue if they feel they are losing more than they gain.

Ongoing exchanges that result in reciprocal benefits foster trust, create interdependence and reduce uncertainty [72, 73]. Relationships are likely to continue through mutual reinforcement and disrupted when someone experiences a lack of symmetry between rewards and costs. This could have implications for (a) older people’s response to a cultural offer as part of social prescribing, (b) interaction between the cultural sector and link workers and (c) the role of the cultural sector in social prescribing for older people.

Social Exchange Theory and our review findings

Social Exchange Theory provides support from existing substantive theory for the key role of tailoring identified within the review—of what is offered, to whom and by whom. Social prescribing can be seen as an exchange between different actors. Our review shows how tailoring forms part of this, as summarised in Table 3, which provides an overview (not necessarily exhaustive) from the literature of potential rewards and costs associated with social exchange and tailoring of cultural offers for older people as part of social prescribing.

Link workers have to invest time and energy into understanding an older person and their needs. They are often paid as an employee for this, but they may receive other benefits (e.g. seeing people they are helping improve their life situation through engaging with a cultural offer). Link workers and cultural sector staff may decide to interact based on anticipated costs and rewards. When an older person gains from a cultural offer, it can foster trust between a link worker and cultural offer provider, although there needs to be a system of communication between these parties so they know that an older person has benefitted from a cultural offer. For an older person to take up (and hopefully sustain) engagement in a cultural offer suggested by a link worker, it is important (at first) that they perceive rewards from the offer as matching or exceeding any costs. What an older person may provide in terms of this exchange includes feedback on a service or showing gratitude to a link worker or cultural sector staff. In terms of benefits for cultural sector providers from engaging in social prescribing, they may receive referrals from a link worker that could diversify the audience engaging with their organisation. They may also receive advice from link workers on how to improve what is provided so it reflects the needs of older people. They are likely to continue providing cultural offers as part of social prescribing if feedback they receive suggests they are making a difference to people’s lives. If they feel that costs associated with such work are not mitigated by the rewards, they may pull back from providing cultural offers.

The overarching concept of tailoring from our review and further understanding brought from Social Exchange Theory emphasise the potential for co-production in ensuring that, as far as possible, cultural offers are shaped to meet the needs and circumstances of older people. Co-production “means delivering public services in an equal and reciprocal relationship between professionals, people using services, their families and their neighbours. Where activities are co-produced in this way, both services and neighbourhoods become far more effective agents of change” [74]. Adopting this approach to service development and delivery can ensure that individuals are working towards a common goal, reforming and potentially improving what is offered. Using co-production has the additional benefit of reducing an older person’s perception that any social exchange they are taking part in is inequitable; it can help them to feel that they can contribute to the development of cultural offers and that their voice is being heard and their ideas valued. For link workers, co-production can broaden the options they have available as offers they are happy to refer people to as part of social prescribing.

Rewards from co-production for any actors must not be undermined by associated costs (some of which are listed in Table 3); this will shape whether all parties remain engaged. It has been noted that co-production is not risk free [75]. Tensions may arise due to the relinquishing of power, conflicting priorities and misunderstandings, alongside the potential need for additional resources and time [76, 77]. If costs outweigh rewards, co-production may not continue.

Discussion

Later life encompasses a variety of needs and circumstances [48, 58] that can influence receptiveness to a cultural offer [55]. Health issues such as dementia or frailty [34, 44], or risk aversion and factors affecting confidence [35, 56, 63], may shape an older person’s response to a link worker’s suggestion that they consider a cultural offer. The pandemic is likely to have heighted these issues for some older people who, our consultations with stakeholders suggested, may worry about safety in venues, and may have experienced a drop in confidence due to social isolation and a disconnection from their usual social networks. We also know that the delivery of social prescribing has changed due to Covid-19, with more interaction between link workers and people they support being undertaken remotely (rather than face-to-face) [78, 79]. Link workers had to be agile in their response to the pandemic [80], as services and activities in the community to refer people on to closed or moved online. It also called for cultural providers to be creative in how they continued to engage with the public when buildings were closed [81,82,83]. The importance of cultural and creative activities in providing people with solace and escapism has been recognised by the Local Government Association [84] in England; it announced a commission to promote the value of cultural provision during and recovery from the pandemic.

Variability in how older people and cultural providers have responded to the pandemic, and how link workers undertake their role, emphasise the importance of tailoring, a key component of our programme theory. For example, link workers must understand an individual and their needs and have a good range of local options to propose to older people [85]. As noted in our programme theory, positive outcomes that may come to older people who engage with cultural offers include being distracted (absorbed), feeling held (e.g. safe and accepted), making connections and transforming through self-growth. In part, this depends on what people are seeking through a cultural offer, which can be explored with a link worker. For some older people, being in a calm or relaxing space may be most important, others may want to learn, whilst for some the social aspect will be key.

As part of tailoring, the cultural sector must be responsive to older people’s needs by addressing things like accessibility and social circumstances (e.g. Covid-19). There will be limits to what is possible in terms of tailoring a cultural offer due to resource constraints and having the time to make changes. It may be a case of tailoring what is essential, which can be decided through co-production of offers with older people. Guidelines for museum and healthcare professionals to tailor activities for older people have been produced [60]. A checklist has also been created of what the cultural sector needs to do to provide an age-friendly environment [57]. Tailoring in this way may help to increase inclusivity in terms of who makes use of cultural offers. Future research could look to creating and evaluating a tailoring checklist to assist cultural providers when thinking about essential things to be accommodated (e.g. transport, toilets, support to attend if lacking confidence). When tailoring is not possible, a cultural offer may only be used by those who would have engaged without being connected through a link worker. This fits with criticism from Weiner [69] that museums tend to work with “known and ‘safe’ communities.” Support from inside and outside an organisation may be required for this to change. Social prescribing could form part of this shift in audience composition.

Training may be helpful for staff if a cultural offer has a social component, so they can support people new to a group; this may include having a range of activities as part of an offer to suit the differing preferences of those present (e.g. listening and watching, discussions, creative tasks, working in pairs) [63]. In terms of training, the pandemic has highlighted that cultural sector staff may require support to deliver attractive and engaging online offers. Likewise, older people may need assisting in their use, and link workers in how to encourage those unfamiliar with digital platforms to try them. During the pandemic, tailoring was required in response to the closure of cultural sector buildings. Digital provision was produced and is likely to form part of delivery going forwards. It has been advised that online offers should be non-patronising and “work to the capabilities not to the limitations of older audiences” [55]. Co-production may assist with this.

Strengths and limitations

Throughout the review, we engaged in conversations with key stakeholders from the cultural sector, social prescribing and with older people, to ensure that our findings resonated with these individuals. A realist approach enabled us to draw on a range of literature. At the point of searching for literature, we found few documents meeting our inclusion criteria that related specifically to the pandemic (due to its recentness). The role of link workers was also missing from most documents we reviewed, as were data on digital offers. We plan to explore these topics in more detail in future research, through primary data collection, using a mixture of qualitative and quantitative methods. This will enable the programme theory presented in this paper to be tested and amended to further understanding of this topic.

We adopted a rapid approach to the review. This meant that the literature search was curtailed, and although extensive (covering grey literature as well as articles in academic journals), it was not exhaustive. There was sufficient information to produce a number of CMOCs that helped us to develop a programme theory that resonated with stakeholders. However, there are elements of our initial broad research question that remain unanswered from our review, which we will seek to address within our planned primary research through a series of interviews with older people and cultural providers, and a questionnaire with link workers.

Conclusions

Tailoring was identified as a key concept within this review to ensure that cultural offers as part of social prescribing meet the needs and aspirations of older people. This has been especially necessarily in light of restrictions imposed by the Covid-19 pandemic across the world. Tailoring can happen at a range of levels (e.g. cultural sector staff being agile and link workers needing to know what older people require and expect). Older people can help with generating appropriate or acceptable cultural offers through feedback and taking a role in co-production. Tailoring can help to ensure that older people benefit from cultural offers; benefits might include a temporary distraction from worries in life, being psychologically held (feeling safe and included), expanding their social network or changing their self-perception. How to tailor cultural offers so they create feelings of safety and connection is an area for further exploration, especially if these offers are to be delivered online as well as in-person. Our review provides some indication of how this might be achieved.

Availability of data and materials

The review drew on published documents that others can access. We have referenced papers included in the review, which others can access should they wish.

References

De Jong GJ, Van Tilburg T. Living arrangements of older adults in the Netherlands and Italy: coresidence values and behaviour and their consequences for loneliness. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 1999;14:1–24.

Luo Y, Hawkley LC, Waite LJ, Cacioppo JT. Loneliness, health, and mortality in old age: a national longitudinal study. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:907–14.

Social isolation, loneliness in older people pose health risks. www.nia.nih.gov/news/social-isolation-loneliness-older-people-pose-health-risks. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

All the lonely people: Loneliness in later life. www.ageuk.org.uk/globalassets/age-uk/documents/reports-and-publications/reports-and-briefings/loneliness/loneliness-report_final_2409.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

Krendl AC, Perry BL. The impact of sheltering in place during the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults’ social and mental well-being. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2021;76:e53–8.

Seifert A, Hassler B. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on loneliness among older adults. Front Sociol. 2020;5:590935.

What is social prescribing? www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/social-prescribing. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

NHS Long term plan. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk. Accessed 20 October 2021.

Social prescribing in Wales. https://primarycareone.nhs.wales/files/social-prescribing/sp-evidence/social-prescribing-final-report-v9-2018-pdf/. Accessed 20 October 2021.

A desk review of social prescribing: From origins to opportunities. www.supportinmindscotland.org.uk/news/social-prescribing-covid-19-rse-report. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

Alderwick HAJ, Gottlieb LM, Fichtenberg CM, Adler NE. Social prescribing in the U.S. and England: emerging interventions to address patients’ social needs. Am J Prev Med. 2018;54:715–8.

Finlay JM, Kobayashi LC. Social isolation and loneliness in later life: a parallel convergent mixed-methods case study of older adults and their residential contexts in the Minneapolis metropolitan area, USA. Soc Sci Med. 2018;208:25–33.

Aggar C, Thomas T, Gordon C, Bloomfield J, Baker J. Social prescribing for individuals living with mental Illness in an Australian community setting: a pilot study. Community Ment Health J. 2021;57:189–95.

Nowak DA, Mulligan K. Social prescribing. Can Fam Physician. 2021;67:88–91.

Tierney S, Wong G, Mahtani KR. Current understanding and implementation of ‘care navigation’ across England: a cross-sectional study of NHS clinical commissioning groups. Br J Gen Pract. 2019;69:e675–81.

Social prescribing: Making it work for GPs and patients. www.bma.org.uk/media/1496/bma-social-prescribing-guidance-2019.pdf. Accessed 08 May 2022.

What is social prescribing? www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/social-prescribing. Accessed 09 May 2022.

Chatterjee HJ, Camic PM, Lockyer B, Thomson LJM. Non-clinical community interventions: a systematised review of social prescribing schemes. Arts Health. 2018;10:97–123.

Can gardens, libraries and museums improve wellbeing through social prescribing? A digest of current knowledge and engagement activities. https://socialprescribing.phc.ox.ac.uk/files/resources/glam-repor-march-2020_rgb-1.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

Delivering participatory theatre during social distancing: what’s working? https://collective-encounters.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Delivering-Participatory-Theatre-During-Social-Distancing-Whats-Working-Low-Res.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

Key workers: Creative ageing in lockdown and after. https://baringfoundation.org.uk/resource/key-workers-creative-ageing-in-lockdown-and-after/. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

Pawson R. The science of evaluation: a realist manifesto. London: Sage; 2013.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realist evaluation. London: Sage; 1997.

Pawson R. Evidence-based policy: a realist perspective. London: Sage; 2006.

Saul JE, Willis CD, Bitz J, Best A. A time-responsive tool for informing policy making: Rapid realist review. Implement Sci. 2013;8:103.

Pluddemann A, Aronson JK, Onakpoya I, Heneghan C, Mahtani KR. Redefining rapid reviews: a flexible framework for restricted systematic reviews. BMJ Evid Based Med. 2018;23:201–3.

Quality standards for realist synthesis (for researchers and peer-reviewers). www.ramesesproject.org/media/RS_qual_standards_researchers.pdf. Accessed 09 May 2022.

Unpacking culture and the well-being of older people during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://socialprescribing.phc.ox.ac.uk/news-views/views/unpacking-culture-and-the-well-being-of-older-people-during-the-covid-19-pandemic. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

Dalkin S, Forster N, Hodgson P, Lhussier M, Carr SM. Using computer assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS; NVivo) to assist in the complex process of realist theory generation, refinement and testing. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2021;24:123–34.

Realist synthesis: RAMESES training materials. www.phc.ox.ac.uk/files/research/realist_reviews_training_materials.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

Age UK. Creative and cultural activities and wellbeing in later life. Published 2018. www.ageuk.org.uk/bp-assets/globalassets/oxfordshire/original-blocks/about-us/age-uk-report%2D%2Dcreative-and-cultural-activities-and-wellbeing-in-later-life-april-2018.pdf. Accessed 12.01.21.

Ander EE, Thomson LJ, Blair K, Noble G, Menon U, Lanceley A, et al. Using museum objects to improve wellbeing in mental health service users and neurological rehabilitation clients. Br J Occup Ther. 2013;76:208–16.

Beauchet O, Barbaros A, Galery K, Vilcocq C. Effect of art museum activity program for the elderly on health: a pilot observational study. Montreal: McGill University; 2018.

Beauchet O, Bastien T, Mittelman M, Hayashi Y, Ho AHY. Participatory art-based activity, community-dwelling older adults and changes in health condition: results from a pre–post intervention, single-arm, prospective and longitudinal study. Maturitas. 2020;134:8–14.

Bengtsson A, Hagerhall C, Englund JE, Grahn P. Outdoor environments at three nursing homes: semantic environmental descriptions. J Hous Elder. 2015;29:53–76.

Bennington R, Backos A, Harrison J, Reader AE, Carolan R. Art therapy in art museums: Promoting social connectedness and psychological well-being of older adults. Arts Psychother. 2016;49:34–43.

Brown Z, Thompson J. Museums, health and social care service. Newcastle: Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums; 2020.

Camic PM, Tischler V, Pearman CH. Viewing and making art together: a multi-session art-gallery-based intervention for people with dementia and their carers. Aging Ment Health. 2014;18:161–8.

Camic PM, Hulbert S, Kimmel J. Museum object handling: a health-promoting community-based activity for dementia care. J Health Psychol. 2019;24:787–98.

Cann PL. Arts and cultural activity: A vital part of the health and care system. Australas J Ageing. 2017;36:89–95.

Culture Health and Wellbeing Alliance. Short report: How creativity and culture has been supporting people who are shielding or vulnerable during Covid-19. Published 2020. www.culturehealthandwellbeing.org.uk/sites/default/files/Short%20report%20-%20How%20creativity%20and%20culture%20has%20been%20supporting%20people%20who%20are%20shielding%20or%20vulnerable%20during%20Covid-19%20-%20UPDATED.pdf. Accessed 12.10.21.

Duncan K. Short narrative report August 2017 - October 2018: Armchair Gallery. Published 2018. http://imaginearts.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/SHORT-AG-Report-2018-compressed.pdf. Accessed 12.10.21.

Fancourt D, Steptoe A, Cadar D. Community engagement and dementia risk: time-to-event analyses from a national cohort study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2020;74:71–7.

Flatt JD, Liptak A, Oakley MA, Gogan J, Varner T, Lingler JH. Subjective experiences of an art museum engagement activity for persons with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease and their family caregivers. Am J Alzheimers Dis Other Dement. 2015;30:380–9.

Ford C. Enriching life with creative expression. Work Older People. 2012;16:111–6.

Ganga RN, Whelan G, Wilson K. Evaluation of the house of memories family carers awareness day. Liverpool: The Institute of Cultural Capital; 2017.

Gould VF. Reawakening the mind: Evaluation of Arts 4 Dementia’s London Arts Challenge in 2012. Published 2013 https://arts4dementia.org.uk/a4d-reports/a4d-report-reawakening-the-mind/. Accessed 12.10.21.

Goulding A. How can contemporary art contribute toward the development of social and cultural capital for people aged 64 and older. Gerontologist. 2013;53:1009–19.

Hendriks I, Meiland FJ, Gerritsen DL, Droes RM. Implementation and impact of unforgettable: an interactive art program for people with dementia and their caregivers. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31:351–62.

Hendriks I, Meiland F, Slotwinska K, Kroeze R, Weinstein H, Gerritsen D, et al. How do people with dementia respond to different types of art? An explorative study into interactive museum programs. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31:857–68.

Howarth M, Griffiths A, da Silva A, Green R. Social prescribing: a ‘natural’ community-based solution. Br J Community Nurs. 2020;25:294–8.

Johnson J, Culverwell A, Hulbert S, Robertson M, Camic PM. Museum activities in dementia care: Using visual analog scales to measure subjective wellbeing. Dementia. 2017;16:591–610.

Joyce C. City Memories: Reminiscence as creative therapy. Qual Ageing Older Adults. 2005;6:34–41.

Liptak A, Tate J, Flatt J, Oakley MA, Lingler J. Humor and laughter in persons with cognitive impairment and their caregivers. J Holist Nurs. 2014;32:25–34.

Lynch E. Ageing well: creative ageing and the city symposium report. Published 2019. https://entelechyarts.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Entelechy-Arts_Creative-Ageing-and-the-City-Symposium.pdf. Accessed 12.10.21.

Mmako NJ, Courtney-Pratt H, Marsh P. Green spaces, dementia and a meaningful life in the community: a mixed studies review. Health Place. 2020;63:102344.

Museum Development North West. Age-friendly museums. Published 2019. https://museumdevelopmentnorthwest.wordpress.com/2019/09/19/new-mdnw-age-friendly-museums-publication/. Accessed 12.10.21.

Roe B, McCormick S, Lucas T, Gallagher W, Winn A, Elkin S. Coffee, cake and culture: Evaluation of an art for health programme for older people in the community. Dementia. 2016;15:539–59.

Schall A, Tesky VA, Adams AK, Pantel J. Art museum-based intervention to promote emotional well-being and improve quality of life in people with dementia: The ARTEMIS project. Dementia. 2018;17:728–43.

Thompson J, Brown Z, Baker K, Naisby J, Mitchell S, Dodds C, et al. Development of the “Museum Health and Social Care Service” to promote the use of arts and cultural activities by health and social care professionals caring for older people. Educ Gerontol. 2020;46:452–60.

Thomson LJM, Chatterjee HJ. Well-being with objects: Evaluating a museum object-handling intervention for older adults in health care settings. J Appl Gerontol. 2016;35:349–62.

Thomson LJ, Lockyer B, Camic PM, Chatterjee HJ. Effects of a museum-based social prescription intervention on quantitative measures of psychological wellbeing in older adults. Perspect Public Health. 2018;138:28–38.

Todd C, Camic PM, Lockyer B, Thomson LJM, Chatterjee HJ. Museum-based programs for socially isolated older adults: understanding what works. Health Place. 2017;48:47–55.

Toepoel V. Cultural participation of older adults: Investigating the contribution of lowbrow and highbrow activities to social integration and satisfaction with life. Int J Disabil Hum Dev. 2011;10:123–9.

Tyack C, Camic PM, Heron MJ, Hulbert S. Viewing art on a tablet computer: a well-being intervention for people with dementia and their caregivers. J Appl Gerontol. 2017;36:864–94.

Tymoszuk U, Perkins R, Spiro N, Williamon A, Fancourt D. Longitudinal associations between short-term, repeated, and sustained arts engagement and well-being outcomes in older adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020;75:1609–19.

Veall D, Arnott R, Bahra H, Boliver L, Booth N, Buruma A, Camic P, Campbell S, Campbell-Gray R, Chatterjee HJ, Day A, Desmarais S, Doane A, Fitzgerald B, Gifford M, Hariprasad J, Hirst K, Johnson J, Kiser R, Kimmel J, Knight D, Lane R, Lockyer B, McDermott T, McDonagh D, Morse N, Muthana A, Nolan C, Phillips L, Pike H, Smith C, Smith H, Thomson L, Wedgebury J., Wenden L, Wilcocks J, Wyche C. Museums on prescription: a guide to working with older people. Published 2017. www.artshealthresources.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/2017-Museums-on-Prescription-Guide.pdf. Accessed on 12.10.21.

Watts E. A handbook for cultural engagement with older men. Published 2015. www.artshealthresources.org.uk/docs/a-handbook-for-cultural-engagement-with-older-men. Accessed on 12.10.21.

Weiner M. Gallery and beyond: training to transform good times. what it takes to build a sustainable creative arts programme for older adults. Published 2014. www.dulwichpicturegallery.org.uk/media/7048/gallery-and-beyond-training-to-transform-good-times.pdf. Accessed on 12.10.21.

Whear R, Coon JT, Bethel A, Abbott R, Stein K, Garside R. What is the impact of using outdoor spaces such as gardens on the physical and mental well-being of those with dementia? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative evidence. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15:697–705.

Homans GC. Social behavior as exchange. Am J Sociol. 1958;63:597–606.

Cook KS, Emerson RM. Power, equity and commitment in exchange networks. Am Sociol Rev. 1978;43:721–39.

Cook KS, Emerson RM. Exchange networks and the analysis of complex organizations. Res Sociol Organ. 1984;3:1–30.

The challenge of co-production. https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/312ac8ce93a00d5973_3im6i6t0e.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct. 2021.

Oliver K, Kothari A, Mays N. The dark side of coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? Health Res Policy Syst. 2019;17:33.

Batalden M, Batalden P, Margolis P, Seid M, Armstrong G, Opipari-Arrigan L, et al. Coproduction of healthcare service. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:509–17.

Holland-Hart DM, Addis SM, Edwards A, Kenkre JE, Wood F. Coproduction and health: public and clinicians’ perceptions of the barriers and facilitators. Health Expect. 2019;22:93–101.

Fixsen A, Barrett S, Shimonovich M. Supporting vulnerable populations during the pandemic: Stakeholders’ experiences and perceptions of social prescribing in Scotland during Covid-19. Qual Health Res. 2022;32:670–82.

Westlake D, Elston J, Gude A, Gradinger F, Husk K, Asthana S. Impact of COVID-19 on social prescribing across an Integrated Care System: a researcher in residence study. Health Soc Care Communit. 2022; [Online ahead of print]. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13802.

Morris SL, Gibson K, Wildman JM, Griffith B, Moffatt S, Pollard TM. Social prescribing during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative study of service providers’ and clients’ experiences. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:258.

Agostino D, Arnaboldi M, Lampis A. Italian state museums during the COVID-19 crisis: from onsite closure to online openness. Mus Manag Curatorsh. 2020;35:362–72.

Khlystova O, Kalyuzhnova Y, Belitski M. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the creative industries: a literature review and future research agenda. J Bus Res. 2022;139:1192–210.

Samaroudi M, Rodriguez Echavarria K, Perry L. Heritage in lockdown: digital provision of memory institutions in the UK and US of America during the COVID-19 pandemic. Mus Manag Curatorsh. 2020;35:337–61.

LGA launches new Commission to promote role of culture in pandemic recovery. www.local.gov.uk/about/news/lga-launches-new-commission-promote-role-culture-pandemic-recovery. Accessed 09 May 2022.

Tierney S, Wong G, Roberts N, Boylan AM, Park S, Abrams R, et al. Supporting social prescribing in primary care by linking people to local assets: A realist review. BMC Med. 2020;8:49.

Acknowledgements

We thank all those who attended our stakeholder meetings. They helped us with sense-checking and alternative ways of thinking about our data.

Funding

This work was funded by UKRI Arts and Humanities Research Council (AH/V008781/1). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and not necessarily those of their host institutions or the funding body.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

NR undertook the literature search. JG and SL were responsible for data screening, extraction and development of CMOCs. ST, GW and KRM developed the initial programme theory and revised this using the CMOCs. ST led on writing the paper. AT, KH, HJC, KE, CP, EW, BM, HW and LS contributed to data analysis during project team meetings and helped to draft the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

As this was a synthesis of published literature, ethics approval was not required.

Consent for publication

N/A.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Overview of included papers.

Additional file 2.

A selection of data extracts used to develop Context-Mechanism-Outcome Configurations (CMOCs), which were also informed by our discussions with stakeholders.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tierney, S., Libert, S., Gorenberg, J. et al. Tailoring cultural offers to meet the needs of older people during uncertain times: a rapid realist review. BMC Med 20, 260 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02464-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-022-02464-4