Abstract

Background

The epidemiology of CNS infections in Europe is dynamic, requiring that clinicians have access to up-to-date clinical management guidelines (CMGs) to aid identification of emerging infections and for improving quality and a degree of standardisation in diagnostic and clinical management practices. This paper presents a systematic review of CMGs for community-acquired CNS infections in Europe.

Methods

A systematic review. Databases were searched from October 2004 to January 2019, supplemented by an electronic survey distributed to 115 clinicians in 33 European countries through the CLIN-Net clinical network of the COMBACTE-Net Innovative Medicines Initiative. Two reviewers screened records for inclusion, extracted data and assessed the quality using the AGREE II tool.

Results

Twenty-six CMGs were identified, 14 addressing bacterial, ten viral and two both bacterial and viral CNS infections. Ten CMGs were rated high quality, 12 medium and four low. Variations were identified in the definition of clinical case definitions, risk groups, recommendations for differential diagnostics and antimicrobial therapy, particularly for paediatric and elderly populations.

Conclusion

We identified variations in the quality and recommendations of CMGs for community-acquired CNS infections in use across Europe. A harmonised European “framework-CMG” with adaptation to local epidemiology and risks may improve access to up-to-date CMGs and the early identification and management of (re-)emerging CNS infections with epidemic potential.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Endemic, epidemic and emerging infectious diseases, including antimicrobial resistant organisms, remain a serious, cross-border threat to health in Europe. The response to these threats needs to be evidence-based and coordinated, and whilst Europe-wide efforts have been made to link and harmonise public health responses, much less has been done in the clinical sphere. The EU-funded Platform for European Preparedness Against R(e-)emerging Epidemics (PREPARE) was established to promote harmonised clinical research studies on infectious diseases with epidemic potential in order to improve patient outcomes and inform public health responses. One issue identified by PREPARE was the lack of understanding of variations in clinical practice across Europe, which may hamper the interpretation of clinical and surveillance data on emerging infectious threats with epidemic potential and impede the implementation of cross-border clinical research.

Central nervous system (CNS) infections continue to affect populations worldwide with high morbidity, mortality and risk of long-term sequelae and are also associated with a range of emerging and re-emerging viral threats to Europe, such as West Nile virus, Toscana virus, measles and enteroviruses [1, 2]. The epidemiology of community-acquired CNS infections is neither fixed nor homogeneous, with changes over time and between locations. The introduction of vaccines has reduced the burden of the two most common etiological agents for bacterial meningitis in adults and older children, Streptococcus pneumoniae and Neisseria meningitidis [3, 4]. Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) is also becoming a rare cause of meningitis in Europe [5]. However, reports of serotype replacement and an increased rate of reduced sensitivity to antimicrobial agents of S. pneumoniae, with varying rates across the region, are a cause of concern, which requires antibiotic regimes to be tailored to regions and travel [3, 5]. Neonatal meningitis is associated with high morbidity and higher incidence compared to older age groups [6]. In neonates, common pathophysiology are primary bloodstream infections with secondary haematogenous distribution to the CNS [6] most commonly caused by Streptococcus agalactiae (group B streptococcus; GBS) or Escherichia coli [3]. Encephalitis, an inflammation of the brain parenchyma associated with high morbidity and risk of long-term sequelae, is commonly caused by viruses [7]. It is estimated that 40 to 60% of cases remain without an aetiological diagnosis [8, 9]. This may partly be due to a lack of consensus on clinical case definitions and standardised diagnostic approaches [10]. The most commonly diagnosed causes of viral CNS infections in Europe are Herpes simplex virus (HSVs), enteroviruses, Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) and arthropod-borne viruses (arboviruses) [11]. The epidemiology of encephalitis is constantly evolving [11], and emerging infectious diseases may present as undifferentiated CNS infections [12]. This is ilustrated by the re-emergence of West Nile virus (WNV) in south-eastern Europe and the emergence of Toscana virus as a leading cause of aseptic meningitis in regions in southern Europe during the summer [13, 14]. Another cause of concern are recent outbreaks of enterovirus-associated severe neurological disease which cause a strain on paediatric intensive care units [15].

Clinical case definitions and clinical management guidelines (CMGs) are important tools for identifying emerging infectious diseases, informing diagnostic and clinical management and providing a degree of standardisation in clinical management practices. In addition, harmonisation of diagnostic and clinical management practices can inform public health outbreak responses and facilitate the design and interpretation of multi-country research, which is a necessity for adequately powered studies of comparatively rare diseases such as CNS infections.

The aim of this review is to identify variations in practices which might be a barrier to the early identification and characterisation of emerging CNS infections with epidemic potential and the implementation of cross-border clinical research as well as public health responses. This is, to our knowledge, the first systematic review and quality appraisal of European CMGs for viral and bacterial CNS infections.

Methods

The systematic review was completed based on a protocol registered in the PROSPERO International prospective register of systematic reviews (ID: CRD42014014212). The protocol was informed by infectious disease specialists and systematic reviewers.

Search strategy

One reviewer conducted the first electronic database search (PubMed, National Guideline Learning Centre, International Guideline Library, TRIP Database) from October 2004 to October 2014. Search terms were as follows: (central nervous system infection [MeSH Terms]) AND (clinical guideline OR clinical practice guideline OR physician guideline OR bedside clinical guideline OR clinical management guideline OR clinical practice protocol OR physician protocol OR clinical management protocol) AND (“last 10 years” [PDat]). An information specialist performed a second updated electronic search of Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid Embase, PubMed, TRIP Database and Google using the exploded thesaurus term “exp Central Nervous System Infections/”, and the free text terms meningitis, encephalitis, meningoencephalitis, combined with a search filter for guidelines to 22 June 2017.

Search terms:

(“Central Nervous System Infections”[Mesh]) OR meningitis [Title/Abstract]) OR meningoencephalitis [Title/Abstract]) OR encephalitis [Title/Abstract])) AND (guideline [Title]) OR guidelines [Title]) OR guidance [Title]) OR protocol [Title]) OR protocols [Title]) OR ((“Guideline” [Publication Type] OR “Guidelines as Topic”[Mesh]) OR “Practice Guideline” [Publication Type])).

TRIP Database and Google were also searched for “meningitis guideline*”, “encephalitis guideline*” and “meningoencephalitis guideline*” up to 31 January 2019. The electronic database searches were supplemented by searching the references of included CMGs and CMGs identified through a brief electronic survey which was e-mailed to 115 clinicians in 33 European countries, through the CLIN-Net clinical network of the COMBACTE-Net Innovative Medicines Initiative [16, 17]. The survey asked clinicians which CMGs they used in their daily practice to identify and manage patients presenting with syndromes of acute, community-acquired CNS infections, and asked them to submit the CMGs via hyperlink or by e-mail. The survey was open from 20 June to 30 December 2016, with two electronic reminders.

Eligibility criteria

Two reviewers screened the title, abstract and full-text guidelines for inclusion. CMGs covering diagnostics and/or clinical management of suspected community-acquired bacterial or viral CNS infections which were aimed at or used by clinicians in Europe and published from 2004 onwards were included. The CMG produced by Médicins Sans Frontières (MSF) aimed at field settings globally was included, as it could be used in Europe in emergency situations. There were no language limitations. Guidelines published in non-English languages were translated using Google Translate and reviewed by a reviewer with good to excellent knowledge of the language. Guidelines that were not aimed at European populations were excluded, unless a clinician responding to the survey reported using them. General antibiotic and local standard operating policies were excluded. Guidelines focused only on patients with specific risk factors, such as HIV, were excluded.

Data extraction

A standardised form for data extraction covering case definitions, diagnostic methods, differential diagnostics and medical management recommendations was developed. One reviewer extracted data from the CMGs and a second reviewer checked the data.

Quality appraisal

The CMGs were critically appraised by two reviewers independently using the Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II (AGREE II) Instrument [18, 19]. The quality was assessed independently by each reviewer for six domains: (1) scope and purpose, (2) stakeholder involvement, (3) rigour of development, (4) clarity of presentation, (5) applicability and (6) editorial independence, and through an overall quality score. Efforts were made to find additional information online on associated webpages for CMGs with limited information about the methodology used. Within each domain, there were a number of sub-criteria to score from 1 to 7 (Additional file 1). A score of one was assigned if there was no information or the criteria was not met; a score of seven when the criteria were met. These scores were summarised for each domain, and the total score for the domain calculated as the percentage of the total possible score for that domain. The final score for each domain was calculated as the average of the reviewers’ scores. Each CMG was also given a total overall quality assessment score based on the average score for all the domains (7 being the highest quality) together with a recommendation for use with or without further modifications.

Results

Clinical management guidelines

A total of 26 CMGs covering community-acquired suspected bacterial or viral CNS infections met the inclusion criteria for the review (Fig. 1). The 26 CMGs were produced in Denmark (n = 2), France (n = 2), Germany (n = 2), Ireland (n = 1), the Netherlands (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), Scotland (n = 1), Spain (n = 3), the UK (n = 6), Europe (n = 3), the USA (n = 3) and MSF (n = 1) (Fig. 2). Ten focused on viral encephalitis/meningoencephalitis, 14 on bacterial meningitis and two on both (Additional file 2).

Of the 76 clinicians (n = 76/115, 66%) from 30 European countries who responded to the survey, 29% reported using CMGs produced by US-based, 27% by national, 23% by local and 14% by European organisations. There were no national CMGs identified from those countries where respondents reported using international CMGs.

Quality appraisal

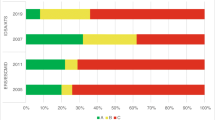

The overall quality of the CMGs ranged from three to seven (Table 1). Ten CMGs were assessed as of high quality (scores 6–7), 12 of medium (scores 4–5) and four of low quality (score ≤ 3). Six CMGs which focused on bacterial CNS infections gained the maximum quality score. Three CMGs scored below 4 and were assessed as in need of modifications in order to adhere to the AGREE II guideline development standards [19]. These modifications included additional information such as the methodology used to identify evidence and formulate recommendations, explicit links between evidence and recommendations and information about stakeholder engagement and peer review. Wide variations in scores between CMGs were seen for “rigour of development”. Seven CMGs scored above 75% for this domain, six of which covered bacterial [2, 5, 20,21,22,23,24], and one viral [22] CNS infections. Most CMGs scored well on “clarity of presentation” and “scope and purpose”. Some score variations may be due to a lack of information presented, such as on stakeholder engagement, editorial independence and plans for regular revisions. This may partly explain the general low scores for “applicability” and “editorial independence”.

Signs and symptoms at presentation

Viral encephalitis/meningoencephalitis

Encephalitis is an inflammation of the brain parenchyma associated with neurological dysfunction [7, 10], which is reflected in the syndromic presentation. Meningoencephalitis affects both the brain parenchyma and meninges [25]. Four of the 12 CMGs covering viral aetiologies described symptoms at presentation in adults [7, 10, 22, 26], four in paediatric populations [7, 10, 27, 28] and six in unspecified populations [25, 29,30,31,32,33] (Table 2). Most of the guidelines cited focal neurological signs, seizures, fever, altered levels of consciousness (ALOC) and changes to personality or behaviour as signs and symptoms of encephalitis in both children and adults. It was noted that objective fever might be lacking at the time of assessment [10, 26] particularly in immunosuppressed patients [10].

Bacterial meningitis

Nine CMGs covering bacterial CNS meningitis presented symptoms at presentation in adults [2, 5, 23, 34,35,36,37,38,39], ten in children [5, 20, 21, 23, 24, 34,35,36, 38, 40], eight in infants [5, 20, 23, 24, 34, 35, 38, 40] and one in unspecified populations [31] (Table 2). The classic symptoms of fever, headache, neck stiffness, followed by altered mental status and petechial rash, were most frequently described for adults and older children. However, for children, there were a wider range of symptoms reported, with some such as leg pain and cold hands and feet specifically described in children. The symptoms in infants and neonates were more general and can be undistinguishable from sepsis [20]. Irritability, fever and poor feeding were most commonly described, followed by bulging fontanelle, petechial rash and lethargy. It was also highlighted by several CMGs that although high fever can be a sign of severity, fever might not always be present [24, 34], particularly in neonates [5, 23, 24, 40]. This is consistent with the conclusions in the recent CMG by the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) that, based on evidence reviews, there are no clinical signs and symptoms that are present in all children [5]. It was also highlighted that the classic signs of meningitis are not always present in adults either [23]. Therefore, bacterial meningitis cannot be ruled out based on the absence of classical signs and symptoms alone [5].

Diagnostic methods

Viral encephalitis/meningoencephalitis

Encephalitis is generally diagnosed based on a combination of clinical, laboratory and neuroimaging features [10, 22]. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) investigation with polymerase chain reaction (PCR) can differentiate common aetiologies [41,42,43]. Epidemiological factors can guide further investigations [22]. Most CMGs recommended urgent blood and CSF sampling, unless lumbar puncture (LP) is contraindicated due to signs of raised intracranial pressure (ICP) (Table 3). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was also recommended when possible, or alternatively computed tomography (CT), since MRI can be useful to detect early changes and for excluding alternative causes and is more sensitive and specific compared to CT [10]. It was highlighted that although some specific changes on MRI have been associated with certain aetiological agents (e.g. HSV and arboviruses), it does not always assist in differentiation and findings might initially be normal [7]. EEG to aid diagnostics was mainly recommended for patients displaying certain symptoms such as altered behaviour or non-convulsive seizures, to exclude non-infectious causes [22].

Bacterial meningitis

All CMGs covering bacterial CNS infections recommended urgent LP and most recommended blood sampling (Table 3), since a positive CSF culture is confirmative of bacterial meningitis and enables in vitro testing of antimicrobial susceptibility to optimise antibiotic treatment, and urgent LP increases diagnostic chances [5]. If CSF examination is not possible, serum markers of inflammation and blood cultures, especially if taken prior to antibiotics, can support the diagnosis and immunochromatographic antigen testing and PCR can provide additional information [5]. The CMG by MSF did not recommend LP for new cases in an epidemic context when a meningococcal aetiology was confirmed [38]. Sixty-nine percent (n = 11/16) recommended a CT scan before LP if clinical signs of raised ICP [2, 5, 23, 31, 34,35,36,37, 39, 40, 44]. In contrast, the CMG by NICE stated that CT is unreliable for identifying raised ICP and recommended clinical assessment instead of CT [24].

Differential diagnostics

Viral encephalitis/meningoencephalitis

There were wide variations in the differential diagnostic recommendations for suspected viral CNS infections, reflecting the many potential causative agents (Table 4). All CMGs recommended testing for HSV and VZV and most also for enteroviruses and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV). Fifty percent recommended testing for parechoviruses [10, 22, 25, 28, 30, 31], with one CMG specifying only in children [31] and three only in children under 3 years old [10, 25, 30]. Other CMGs recommended testing for Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), human herpesvirus [6, 7], adenoviruses and, depending on season or exposure, arboviruses. Testing for influenza, mumps, measles and rubella were also recommended, especially during an on-going epidemic [30]. Many, but not all CMGs provided differential diagnostic tables based on risk factors, such as age, immune status, travel, animal contact and seasonality [7, 10, 22, 25, 27,28,29]. It was noted by some that PCR, e.g. for HSV, the most commonly diagnosed aetiological agent, can be falsely negative, especially in children and early disease course [10]. If a test is negative and still concerns about the diagnosis, it was recommended to take a second CSF sample within 3 to 7 days [7, 10, 22]; one CMG specified a minimum of 4 days after onset of neurological symptoms [26].

Bacterial meningitis

There was consensus on the initial differential diagnostics for adults and older children presenting with syndromes suggestive of bacterial meningitis (Table 5). Besides two CMGs which only focused on N. meningitidis [20, 21], all recommended testing for N. meningitidis and S. pneumoniae in adults and children, but with variations in recommendations for Hib testing. Most also recommended testing for L. monocytogenes in adults; four specified for adults over 50 years [5, 31, 39, 44], and one in adults over 60 years [2]. Additional risk groups for L. monocytogenes were specified as adults over 18 years old with chronic conditions causing immunosuppression [2, 5, 25, 36, 39].

The different epidemiology for neonatal meningitis was reflected in the eight CMGs providing recommendations for neonates. All recommended testing for GBS, most also for E. coli (n = 7) and L. monocytogenes (n = 7). There were variations in the definitions of risk groups for neonates and infants. The CMG produced by MSF recommended testing for GBS and Gram-negative bacteria up to 7 days of age and S. pneumoniae and L. monocytogenes in more than 7-day-old neonates [38]. Two CMGs recommended using the neonate recommendations in infants up to 3 months of age [24, 38]. For infants beyond the neonatal period, most recommended testing for N. meningitidis (n = 11), S. pneumoniae (n = 10) and Hib (n = 6), again with variations in the age cut-offs.

Empirical treatment

Viral encephalitis/meningoencephalitis

Although a wide range of viruses can cause CNS infections, the treatment options are limited. Early treatment using acyclovir (I.V.) pending diagnosis was recommended by the CMGs focused on viral CNS infections that included treatment recommendations [7, 22, 26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33] since early treatment with acyclovir has been associated with a lower risk of sequelae and death from the most commonly diagnosed cause, HSV [7] (Table 6). The recommended dose for adults or unspecified populations was 10 mg/kg I.V. with a recommended duration varying from 10 to more than 14 days. A CMG from France (2017) recommended the addition of amoxicillin in adults to cover for risk of L. monocytogenes [26]. The dose for children ranged from 10 to 20 mg/kg acyclovir I.V. for 14 to more than 21 days [27, 28], to 20 mg/kg I.V. for neonates for at least 14 days [27, 28, 32]. It was noted that treatment and duration should be assessed depending on additional symptoms and modified depending on diagnostic results.

Bacterial meningitis

All 15 CMGs covering treatment recommended urgent administration of antibiotics on clinical suspicion of bacterial meningitis (Table 7). Thirty-three percent (n = 5/15) specified a time-frame for administration, ranging from within one [2, 5] to three [34, 36, 37] hours. Forty-seven percent (n = 7/15) recommended pre-hospital antibiotics if the patient initially presents to a healthcare setting outside of a hospital. One CMG noted that there are no prospective clinical data on the relationship of the timing of antimicrobial administration to clinical outcome in patients with bacterial meningitis, but since it is a neurologic emergency, appropriate therapy is recommended as soon as possible after the diagnosis is considered likely [44]. It was highlighted that the choice of antibiotics should be informed by risk factors for different aetiologies, such as age and risk of reduced susceptibility to penicillin and third-generation cephalosporins [5]. This was reflected in the CMGs, though with variations in specification of at-risk groups. Most recommended a third-generation cephalosporin alone [5, 34,35,36, 38, 39, 44] or in combination with a penicillin for all adults [2, 23, 37], “elderly” [36] and over 50 [5, 39, 44] or over 60 years [2], due to higher risk of L. monocytogenes infection in these risk groups [5, 34, 36, 39]. Most guidelines that provided recommendations for neonates recommended a third-generation cephalosporin plus penicillin [5, 20, 23, 24, 35, 38, 40, 44] or alternatively an aminoglycoside with penicillin [5, 35, 38, 44]. However, the age cut-off for these recommendations varied, ranging from 1 [5, 23, 44], to 2 [35], or 3 months of age [20, 24, 38, 40]. For older infants and children, there was consensus on the recommendations of a third-generation cephalosporin alone [5, 19,20,21, 23, 34,35,36, 38]. The guideline by MSF recommended a cephalosporin in an epidemic context where N. meningitides is the most likely pathogen, and addition of cloxacillin if associated skin or umbilical cord infection for all age-groups [38].

Many CMGs recommended the addition of vancomycin [2, 5, 34,35,36,37, 39, 40] alternatively rifampicin [2, 5, 37, 39] if there is suspicion of reduced sensitivity to penicillin, except for neonates. However, the CMGs produced by IDSA (USA) and NICE (UK) gave different advice. The first recommended vancomycin to everyone except neonates (< 28 days old) [44], whereas the CMG by NICE recommended vancomycin to all returning travellers or those with recent prolonged or multiple exposure to antibiotics within the past 3 months, to cover risk of penicillin-resistant strains of S. pneumoniae [24].

All CMGs focused on bacterial CNS infections recommended adjunctive corticosteroids therapy before or with first dose of antibiotics. Some recommended it up to a few hours [37], 4 h [5, 39], 12 h [2, 24] or 24 h post-antibiotics [20, 35]. Four explicitly did not recommend steroids for patients with immunosuppression [34] or for neonates [5, 24, 44]. One CMG noted that corticosteroids in infants is controversial and only recommended for Hib meningitis [44]. It was highlighted that corticosteroids can reduce inflammation and brain oedema and has in some studies shown benefits of reducing rates of complications and improving outcomes in patients with meningitis, but also that some studies have raised concerns about potential side effects [2].

Discussion

The data highlights the wide range of CMGs for acute, community-acquired CNS infections in use across Europe and variations in quality, clinical case definitions for guiding identification and in initial clinical recommendations. Most CMGs were produced by national or European organisations. Several survey respondents reported using CMGs produced by other countries in or outside of Europe, which may have implications for timely identification of causative pathogens and use of antibiotics, unless they are adapted to regional epidemiology.

There were several high-quality CMGs that adhered to most of the standards set out in the AGREE II tool. All of the highest scoring CMGs were focused on bacterial aetiologies. Many were more than 3 years old, which is the recommended time-frame for re-assessment of validity [18, 45, 46]. This is a concern in light of the rapidly changing epidemiology of infections and antimicrobial resistance. The most recent Europe-wide CMG on bacterial meningitis was published in 2016 [5], whilst the most recent Europe-wide CMG for viral CNS infections was updated in 2010 [32]. Though there might be additional CMGs not identified through the review or survey, this, together with the fact that many survey respondents used international CMGs, highlights a need for an updated European-wide CMG covering viral CNS infections in adult and paediatric populations that can be adapted nationally.

There was a general consensus on diagnostic methods, but wider variations in infectious disease differential diagnostics recommendations, especially for paediatric and elderly populations. There was also general consensus on the most common bacterial causative agents for adults and older children, but variations in differential diagnostic recommendations for infants, neonates and elderly and in the definitions of these risk groups. This is illustrated by the different risk groups identified for L. monocytogenes infection, which in two CMGs were defined as adults over 50 years [5, 44], whereas over 60 years in another [2]. It is also illustrated by the wide variations in the definition of risk groups for GBS, defined as younger than 1 week [38], 28 days [2, 5, 23, 24, 45], 3 months [34, 40] or 24 months [44] in the recommendations for neonates and infants.

In regard to empirical treatment, there was general consensus on recommended initial therapy for suspected viral aetiologies, pending diagnostics. Moreover, there was a consensus across CMGs on the need for urgent I.V. antibiotics on clinical suspicion of bacterial meningitis. However, only about half recommended pre-hospital antibiotics when presenting outside of a hospital setting. All CMGs recommended a third-generation cephalosporin for suspected bacterial aetiologies, to cover the most common pathogens in adults and children, but with variations in recommendations for adding penicillin to cover L. monocytogenes. Most of the European CMGs recommended the addition of vancomycin or rifampicin if decreased susceptibility to penicillin or third-generation cephalosporin is suspected based on geographical regions visited, whereas the CMG by NICE recommended it to all returning travellers [24]. The CMG by IDSA aimed at all global settings recommended vancomycin to everyone beyond neonatal age [44], which highlights the risk of inappropriate antibiotics usage unless adapted to regional epidemiology.

Some of the variations in recommendations can be explained by regional differences in epidemiology and risks of reduced sensitivity to antimicrobial agents. ECDC data from 2015 shows wide variations in reduced penicillin resistance rates of S. pneumoniae from 0.6% in Belgium, to more than 20% in Slovakia, Bulgaria, France, Spain, Iceland, Poland, Malta and Romania [47]. The variations in recommendations seen between CMGs produced in Europe, compared to those produced outside of Europe, but used by clinicians in Europe, indicate risks of inappropriate differential diagnostic requests and antimicrobial treatment regimes, unless the guidelines are adapted to national settings. This may lead to delayed identification of diseases and inappropriate initial management. The variations seen in recommendations for paediatric and elderly populations and the limited number of CMGs covering these populations also indicate a need to ensure equity in access to CMGs covering all different at-risk population, as well as region-appropriate recommendations.

The review highlights a need for clinicians to ensure that CMGs are robustly developed, up-to-date and appropriate for the setting and population. In an increasingly global world, it is important to ensure CMGs also address risks of travel-imported infections. Some CMGs addressed this by providing tables based on risk factors [7, 10], or links to websites with up-to-date international surveillance data and risk assessments [5], such as the ECDC and the World Health Organizations websites. This highlights the importance of these websites to provide current data about the epidemiology of circulating infections and the risk of antibiotic-resistant strains globally. Other variations reflect limitations in the evidence available, such as the definition of risk groups for infections and effective treatment strategies for these. Furthermore, the limitations in evidence was also reflected in the variations in recommended timing of antibiotics and corticosteroids for bacterial CNS infections, which was also noted in a recent review [3].

This review highlights important differences in quality, coverage and initial clinical recommendations between the CMGs. The AGREE II tool was useful for assessing the quality of the CMGs. It may be used together with other tools, such as the 4-item Global Rating Scale (GRS), but a comparison showed that the GRS is less sensitive in detecting differences in guideline quality [48]. There are limitations to the review, in only including CMGs which were published or accessible via the survey, and despite the lack of language restrictions, most CMGs identified were produced in English or by EU/EEA member states. Furthermore, the data extraction was limited to parameters associated with the early identification and initial management of syndromes of community-acquired CNS infections, to assess variations which could impact on the early identification, management and control of emerging infections with epidemic potential. Antibiotic dosage was not presented, as this is a clinical decision which may be affected by individual patient characteristics. The review does not attempt to create a new guideline, but to highlight important limitations and differences in CMGs in use across Europe, identifying the need to update recommendations and harmonise standards in order to inform future research needs and CMG development.

Despite these limitations, this review highlights variations in quality and recommendations between the CMGs, which may be barriers for the rapid identification and management of CNS infections which may have an impact on health outcomes and timely identification of emerging outbreaks. Considering the resources required to develop complex, evidence-based CMGs, not all health systems might have the resources required. A “framework-CMG” produced by an international network of appropriate experts and stakeholders can provide a useful model for CMG development, as evident by the high-quality CMGs identified, some of which have been adopted by clinicians in several countries. This internationally produced framework CMG would need to address regional risks and consider resources for regular review, updating and dissemination. This model can also improve harmonisation of case definitions and recommendations, which can facilitate equity in access to best available evidence-based recommendations, rapid identification of emerging infections and clinical, research and public health responses to epidemics. The recent guideline on bacterial CNS infections produced by ESCMID [5] is a good example of a robust, comprehensive CMG aimed at a Europe-wide audience, which can serve as a model to be adapted to regional epidemiology as appropriate and monitored for uptake across the region.

Conclusions

This review highlights variations in the quality and recommendations of CMGs for community-acquired CNS infections in use across Europe. A harmonised European framework-CMG with adaptation to local epidemiology and risks may improve access to up-to-date CMGs and the early identification and management of (re-) emerging CNS infections with epidemic potential. The review particularly highlights the need for an updated European CMG for infectious encephalitis, which covers all risk groups, including paediatric and elderly populations. Further research into risk groups for infections and effective treatment strategies to target these populations is required.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article [and its Additional files].

Abbreviations

- AEPED:

-

Asociación Española de Pediatría

- AGREE II:

-

Appraisal of Guidelines for Research and Evaluation II

- ALOC:

-

Altered level of consciousness

- AMS:

-

Altered mental status

- BIA: ABN:

-

British Infection Association: Association of British Neurologists

- BPAIIG:

-

The British Paediatric Allergy Immunology and Infections Group

- CLIN-Net:

-

Clinical investigator network

- CMG:

-

Clinical management guideline

- CMV:

-

Cytomegalovirus

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- COMBACTE-Net:

-

Combatting antibiotic resistance in Europe-network

- CSF:

-

Cerebral spinal fluid

- CT:

-

Computerised tomography

- DGN: BM:

-

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie: Bakterielle Meningoenzephalitis

- DGN: VM:

-

Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie: Virale Meningoeczephalitis

- DNS:

-

Dansk Neurologisk Selskab

- DSI:

-

Dansk Selskab for Infektionsmedicin

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus

- ECDC:

-

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

- EEA:

-

European Economic Area

- EEG:

-

Electroencephalogram

- EFNS:

-

European Federation of Neurological Societies

- ESCMID:

-

European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases

- EU:

-

European Union

- GBS:

-

Streptococcus agalactiae; group B streptococcus

- GRS:

-

Global Rating Scale

- HHV:

-

Human herpesvirus

- Hib:

-

Haemophilus influenzae type B

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HPSC:

-

Health Protection Surveillance Centre

- HSV:

-

Herpes simplex virus

- ICP:

-

Intracranial pressure

- IDSA:

-

Infectious Diseases Society of America

- IEC:

-

International Encephalitis Consortium

- I.V.:

-

Intravenous

- JEV:

-

Japanese encephalitis virus

- LP:

-

Lumbar puncture

- MeSH:

-

Medical subject headings

- MHSSE:

-

Ministry of Health, Social Services and quality

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- MSF:

-

Médicins Sans Frontières

- NICE:

-

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

- NNF:

-

Norsk Nevrologisk Forening

- NVN:

-

Nederlandse Vereniging voor Neurologie

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PHE: ME:

-

Public Health England: Meningoencephalitis

- PHE: VE:

-

Public Health England: Viral Encephalitis

- PREPARE:

-

Platform for European Preparedness Against (Re-)emerging Epidemics

- PROSPERO:

-

International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews

- RSV:

-

Respiratory syncytial virus

- SIGN:

-

Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network

- SPILF:

-

Société de Pathologie Infectieuse de Langue Française

- TBEV:

-

Tick-borne encephalitis virus

- TRIP:

-

Turning research into practice

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- UKJSS:

-

UK Joint Specialist Societies

- VZV:

-

Varicella-zoster virus

- WNV:

-

West Nile virus

References

Sundaram C, Shankar SK, Thong WK, Pardo-villamizar CA. Pathology and diagnosis of central nervous system infections. SAGE-Hindawi Access Res Pathol Res Int. 2011;2011:8782–63.

McGill F, Heyderman RS, Michael BD, Defres S, Beeching NJ, Borrow R, et al. The UK joint specialist societies guideline on the diagnosis and management of acute meningitis and meningococcal sepsis in immunocompetent adults. J Infect. 2016;72(4):405–38.

van Ettekoven CN, van de Beek D, Brouwer MC. Update on community-acquired bacterial meningitis: guidance and challenges. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(9):601–6.

McIntyre PB, O'Brien KL, Greenwood B, van de Beek D. Effect of vaccines on bacterial meningitis worldwide. Lancet. 2012;380(9854):1703–11.

van de Beek D, Cabellos C, Dzupova O, Esposito S, Klein M, Kloek AT, et al. ESCMID guideline: diagnosis and treatment of acute bacterial meningitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2016;(22):S37-S62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2016.01.007.

Ku LC, Boggess KA, Cohen-Wolkowiez M. Bacterial meningitis in the infant. Clin Perinatol. 2015;42(1):29–45.

Tunkel AR, Glaser CA, Bloch KC, Sejvar JJ, Marra CM, Roos KL, et al. The management of encephalitis: clinical practice guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;47:303–27.

Glaser CA, Gilliam S, Schnurr D, Forghani B, Honarmand S, Khetsuriani N, et al. In search of encephalitis etiologies: diagnostic challenges in the California encephalitis project, 1998-2000. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36(6):731–42.

Granerod J, Ambrose HE, Davies NW, Clewley JP, Walsh AL, Morgan D, et al. Causes of encephalitis and differences in their clinical presentations in England: a multicentre, population-based prospective study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2010;10(12):835–44.

Venkatesan A, Tunkel AR, Bloch KC, Lauring AS, Sejvar J, Bitnun A, et al. Case definitions, diagnostic algorithms, and priorities in encephalitis: consensus statement of the international encephalitis consortium. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:1114–28.

Boucher A, Herrmann JL, Morand P, Buzele R, Crabol Y, Stahl JP, et al. Epidemiology of infectious encephalitis causes in 2016. Med Mal Infect. 2017;47(3):221–35.

Mailles A, Stahl JP, Bloch KC. Update and new insights in encephalitis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017;23(9):607–13.

Charrel RN, Gallian P, Navarro-Marí J-M, Nicoletti L, Papa A, Sánchez-Seco MP, et al. Emergence of Toscana virus in Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11(11):1657–63.

Sigfrid L, Reusken C, Eckerle I, Nussenblatt V, Lipworth S, Messina J, et al. Preparing clinicians for (re-)emerging arbovirus infectious diseases in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018;24(3):229–39.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Rapid Risk Assessment - Enterovirus detections associated with severe neurological symptoms in children and adults in European countries. Stockholm: ECDC; 2016. [cited 2017 27 Nov]

ND4BB COMBACTE. CLIN-Net the Netherlands2019. Available from: https://www.combacte.com/about/clin-net/. [cited 2019 feb]

UMC Utrecht Julius Centre. Research Online Utrecht. the Netherlands; 2019. Available from: http://portal.juliuscentrum.nl/research/en-us/home.aspx. [cited 2019 Feb]

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. AGREE II: advancing guideline development, reporting and evaluation in health care. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1308–11.

AGREE Next Steps Consortium. The AGREE II Instrument [Electronic version] 2009 Available from: http://www.agreetrust.org. [cited 2017 5 Dec]

SIGN. Management of invasive meningococcal disease in children and young people: a national clinical guideline Scotland 2008 [cited 2018 April].

Álvarez JCB, Villena AE, Moya JMG-L, Benavent PG, Dios JGd, Hoyos JAGd, et al. Clinical practice guidelines in the Spanish NHS: clinical practice guideline on the management of invasive meningococcal disease 2013 [cited 2018 March].

Solomon T, Michael BD, Smith PE, Sanderson F, Davies NWS, Hart IJ, et al. Management of suspected viral encephalitis in adults - Association of British Neurologists and British Infection Association National Guidelines. J Infect. 2012;64:347–73.

van de Beek D, Brouwer MC, de Gans J, Verstegen MJT, Spanjaard L, Pajkrt D, et al. Richtijn Bacteriële Meningitis 2013 [cited 2018 March].

NICE Clinical Guidelines No. 102. Meningitis (bacterial) and meningococcal septicaemia in under 16s: recognition, Diagnosis and management UK2015 [cited 2019 Feb].

PHE. UK standards for microbiology investigations: meningoencephalitis UK: PHE; 2014. Available from: www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/344105/S_5i1.pdf. [cited 2018 March]

Stahl JP, Azouvi P, Bruneel F, Broucker T, Duval X, Fantin B, et al. Guidelines on the management of infectious encephalitis in adults. Med Mal Infect. 2017;47(3):179-94.

Navarro Gómez M, González F, Santos Sebastián M, Saavedra Lozano J, Hernández Sampelayo Matos T. Encefalitis Spain: AEPED; 2011 [cited 2018 March].

Kneen R, Michael BD, Menson E, Mehta B, Easton A, Hemingway C, et al. Management of suspected viral encephalitis in children - Association of British Neurologists and British Paediatric Allergy, Immunology and Infection Group National Guidelines. J Infect. 2012;64:449–77.

Skovbølling SL, Pleger C. Encephalitis Stratgidokument 2015 [cited 2018 March].

PHE. UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations: Investigation of Viral Encephalitis (G4: Investigations of Viral Encephalitis and Meningitis) UK, PHE, 2014 (cited 2018 March).

Norsk nevrologisk forening. Veileder I akuttnevrologi Norway2016 [cited 2018 March].

Steiner I, Budka H, Chaudhuri A, Koskiniemi M, Sainio K, Salonen O, et al. Viral meningoencephalitis: a review of diagnostic methods and guidelines for management. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17:999–1009.

Uta-Meyding-Lamadé. Virale Meningoenzephalitis Stuttgart: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie; 2012 [cited 2018 March].

Guery B, Roblot F, Gauzit R, Varon E, Lina B, Bru P, et al. Practice guidelines for acute bacterial Meningitidis (except newborn and nosocomial meningitidis): short version. Med Mal Infect. 2008;39:356–67.

O’Flanagan D, Bambury N, Butler K, Cafferkey M, Cotter S, McElligott P, et al. Guidelines for the early clinical and public health management of bacterial meningitis (including meningococcal disease) 2015 [cited 2018 March].

Chaudhuri A, Martin PM, Kennedy PGE, Andrew Seaton R, Portegies P, Bojar M, et al. EFNS guideline on the management of community-acquired bacterial meningitis: report of an EFNS task force on acute bacterial meningitis in older children and adults. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:649–59.

Pfister H. Ambulant erworbene bakterielle (eitrige) Meningoenzephalitis. Stuttgart: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie; 2012. Report No.: 313155455X

MSF. Bacterial meningitis. In: Grouzard V, Rigal J, Sutton M, editors. Clinical guidelines diagnosis and treatment manual; 2016. p. 175–9.

Lebech A, Hansen B, Brandt C, von Lüttichau H, Bodilsen J, Wiese L, et al. Rekommandationer for initial behandling af akut bakteriel meningitis hos voksne. Denmark: Dansk Selskab for Infektionsmedicin; 2018.

Artigao F, Lopez R, Castillo Martin del F. Meningitis bacteriana. Spain: Protocolos de la AEP. 3; 2011. p. 47–57.

Khatib U, van de Beek D, Lees JA, Brouwer MC. Adults with suspected central nervous system infection: a prospective study of diagnostic accuracy. J Infect. 2017;74(1):1–9.

McGill F, Griffiths MJ, Bonnett LJ, Geretti AM, Michael BD, Beeching NJ, et al. Incidence, aetiology, and sequelae of viral meningitis in UK adults: a multicentre prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(9):992–1003.

Brouwer MC, van de Beek D. Viral meningitis in the UK: time to speed up. Lancet Infect Dis. 2018;18(9):930–1.

Tunkel A, Hartman B, Kaplan S, Kaufman B, Roos K, Scheld W, et al. Practical guidelines for the management of bacterial meningitis: Infectious Diseases Society of America; 2004 [cited 2017 21 Dec].

Shekelle P, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, Woolf SH. When should clinical guidelines be updated? BMJ. 2001;323:155–7.

Shekelle PG, Ortiz E, Rhodes S, Morton SC, Eccles MP, Grimshaw JM, et al. Validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical practice Guidelines. JAMA. 2001;286:1461–7.

European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Antimicrobial resistance surveillance in Europe 2015. Stockholm: ECDC; 2017.

Brouwers MC, Kho ME, Browman GP, Burgers JS, Cluzeau F, Feder G, et al. The global rating scale complements the AGREE II in advancing the quality of practice guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2017;65:526–34.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Belmira Belić and Miranda Hopman at the Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, European Projects University Medical Center Utrecht, for distributing the electronic survey and to all clinicians who responded to the survey.

Funding

This work forms part of the platform for the European preparedness against (re-)emerging epidemics (PREPARE) Work Package 2. PREPARE is funded by the European Commission’s FP7 Programme grant number 602525. This research was partially funded by the University Of North Carolina School Of Medicine International Health Fellowship Award.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CP, LS, AR and PH designed the project. AR and EH carried out the systematic evidence search. LS, AR and CP screened returned search results. AR, CP, LS and SL independently extracted data from guidelines. The CMGs were critically appraised by CP and LS. KSL, GC, LS and PH distributed the survey. KSL, SL and LS screened the survey results. CP and LS drafted the publication with contributions from SL, JL, EH, HG and PH. All authors reviewed and approved the final content for publication.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

AGREE II Instrument for the Quality Assessment of Clinical Management Guidelines (PDF 76 kb)

Additional file 2:

Clinical management guidelines included in the review (PDF 57 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Sigfrid, L., Perfect, C., Rojek, A. et al. A systematic review of clinical guidelines on the management of acute, community-acquired CNS infections. BMC Med 17, 170 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1387-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-019-1387-5