Abstract

Background

Human babesiosis, caused by parasites of the genus Babesia, is an emerging and re-emerging tick-borne disease that is mainly transmitted by tick bites and infected blood transfusion. Babesia duncani has caused majority of human babesiosis in Canada; however, limited data are available to correlate its genomic information and biological features.

Results

We generated a B. duncani reference genome using Oxford Nanopore Technology (ONT) and Illumina sequencing technology and uncovered its biological features and phylogenetic relationship with other Apicomplexa parasites. Phylogenetic analyses revealed that B. duncani form a clade distinct from B. microti, Babesia spp. infective to bovine and ovine species, and Theileria spp. infective to bovines. We identified the largest species-specific gene family that could be applied as diagnostic markers for this pathogen. In addition, two gene families show signals of significant expansion and several genes that present signatures of positive selection in B. duncani, suggesting their possible roles in the capability of this parasite to infect humans or tick vectors.

Conclusions

Using ONT sequencing and Illumina sequencing technologies, we provide the first B. duncani reference genome and confirm that B. duncani forms a phylogenetically distinct clade from other Piroplasm parasites. Comparative genomic analyses show that two gene families are significantly expanded in B. duncani and may play important roles in host cell invasion and virulence of B. duncani. Our study provides basic information for further exploring B. duncani features, such as host-parasite and tick-parasite interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human babesiosis, caused by the genus Babesia, is an emerging and reemerging tick-borne infectious disease that is mainly transmitted by tick bites, blood product transfusion, and congenitally. There is a broad agreement that the main causative agents of human babesiosis are B. microti, B. divergens, B. duncani, B. crassa, and B. motasi [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Symptoms of babesiosis include fever, headache, multi-system organ failure, and even death [7, 8]. In recent years, an increasing number of cases of human babesiosis have drawn people’s attention. During the past decades, the majority of knowledge has been obtained about B. microti, which is responsible for the majority of Babesia species infections in humans throughout the world. Traditionally, other Babesia spp. have been neglected because they cause relatively fewer cases in comparison with B. microti [9]. Compared with B. microti, B. duncani is characterized by a rapid increase in parasitemia and severe pathology, with mortality rates of around 95% in infected C3H, A/J, AKR/N, and DBA/1J mice [10, 11]. The recent emergence of significant human babesiosis cases caused by B. duncani in the Pacific coast region, as well as the observation of severe and even fatal human cases, has stimulated interest in this enigmatic species, including its biological features, phylogenetic relationships, and adaptive evolution.

As the highest virulent Babesia species as-confirmed in animal models (such as in mice and hamsters), B. duncani was first reported in a 41-year-old man who contracted human babesiosis in Washington state in 1993 [12]. Since then, additional cases caused by this pathogen were documented in California and Canada [13, 14]. Earlier studies confirmed B. duncani in a clade with parasite B. conradae isolated from canines in California, based on its phylogenetic analysis targeting the 18S rRNA gene, whereas by targeting the ITS (Internal transcribed spacer) gene, B. duncani was placed in a distinct clade from other known Babesia spp. [15]. However, those controversial conclusions were recently challenged with the completeness of mitochondrial genome sequencing that placed this parasite in a clade with T. orientalis and T. parva, infecting buffo and cattle, respectively, but distinct from other Babesia spp. and Plasmodium spp. [16]. The updated phylogeny-based classification of the Piroplasmida is challenging the previous taxonomic evolutionary analysis. Babesia spp. form a polyphyletic group, in terms of their phenotype and life history, which provides valuable information for understanding the taxonomy of the Piroplasmida [17]. The B. duncani lineage is classified as Babesia sensu lato, suggesting that B. duncani belongs to clade III of Piroplasmida [18].

In this context, we use genomic and transcriptomic data derived from B. duncani merozoites to assemble a reference genome and to perform a comparative analysis of genomes from apicomplexan parasites. Our analyses provide a better understanding of its evolution and key features correlated with its biology, such as gene family expansion and host cell invasion.

Results and discussion

Genome assembly and annotation

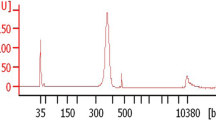

Babesia duncani genome was sequenced using ONT and Illumina platforms. Long reads derived from ONT (182,649 reads, median length 25,597 bp, total bases 4.7 Gb) were assembled into the draft assembly, which was further corrected using ONT long reads and Illumina reads (length 150 bp, total paired sequences 9,442,873, total bases 2.2 Gb). The overall coverage of sequencing data was evaluated using Jellyfish v2.3.0 (Fig. 1a) [19]. Eventually, a total length of 7.9 Mb with seven scaffolds was generated, which size is comparable to B. microti, B. bovis, and Babesia sp. Xinjiang, ranging from 6.4 to 8.4 Mb. However, the B. duncani genome is the second smallest Babesia spp. genome. GC content is similar between B. microti and B. duncani (Table 1), but lower than other Piroplasm parasites, such as B. bovis, B. bigemina, and B. ovata. Babesia duncani genome contains 9.1% repeated sequences, including 8.8% of unclassified repeats and 0.2% simple repeats, and classic transfer RNA genes. The completeness of the genome, evaluated by BUSCO (v5.1.3) using the core apicomplexan dataset (apicomplexa_odb10), was 95.3% [20]. Comparisons of B. duncani reference genome with these of B. bovis and B. microti reveal some common features, including a similar GC content, some degree of collinearity, rearrangements of large fragment, and conservation of gene content (Table 1, Figs. 2, and 3a).

Phylogenetic relationship with other Apicomplexa parasites and critical features of their genomes. a Circular plot shows basic features of the B. duncani genome assembly. From the outermost to the innermost ring: density of short interspersed elements, levels of gene expression, % of GC content, density of gene model, and gene family of blf 1. b Maximum likelihood species tree of Apicomplexa parasites was constructed based on a concatenated alignment of 493,035 amino acids from 310 single-copy orthologous genes. The rooting of the tree at Therahymena thermophila is based on a previously documented Babesia phylogenetic relationship [21]. Bootstrap values were shown on each node

We predicted 3759 protein-coding genes in the B. duncani genome, which is similar in the number of genes to those of other Babesia spp., 61.4% of which were proved by RNA-Seq data. Almost half of these genes (1636 genes) were annotated to Gene Ontology (GO) terms (Additional file 1: Table S1). A total of 369 (9.8%) of predicted proteins contained signal peptide sequences. A total of 1625 genes are lacking introns, and the remaining 2134 (56.8%) genes are present with one or several introns. The percentages of genes containing one or even more introns are almost similar in lineage-specific gene families (52/89, 58.4%) and expanded gene families (12/21, 57.1%), whereas a significantly high percentage of multiple introns genes is observed in conserved housekeeping genes (1279/1900, 67%) (p < 0.01). Gene length is a positive correlation with the number of exons (Fig. 1b).

Phylogenetic relationship with other Apicomplexa parasites

There is an agreement that mitochondrial protein-coding sequences are commonly used to investigate the evolutionary and phylogenetic relationships of apicomplexan parasites. Recently, analysis of cytochrome c oxidase subunit I (CoxI), cytochrome b (Cob) protein sequences, and 18S rRNA revealed that B. duncani was defined in a clade with Theileria spp. (including T. orientalis and T. parva), whereas it has a relatively remote phylogenetic relationship with Babesia spp .[16, 17]. In addition, to provide a reliable evolutionary position of B. duncani and fully analyze the relationship between this parasite with Apicomplexa parasites, 310 single-copy orthologous nuclear genes from 18 species across Apicomplexa were used to reconstruct maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees. Our result is consistent with the previous results, based on the analysis of CoxI and Cob sequences, that B. duncani is ascribed to a new lineage distinct from B. microti, B. bovis, Theileria spp., and Plasmodium spp. [16]. It is noted that when B. microti is included, Babesia spp. are paraphyletic, with sister-group relationships of B. bigemina and B. ovata with Babesia sp. Xinjiang and B. bovis. In contrast to the previous results that ascribed a close relationship between B. duncani and two Theileria spp. (T. orientalis and T. parva), this parasite falls in the same group as four other Babesia spp. (B. bigemina, B. ovata, Babesia sp. Xinjiang, and B. bovis), but itself forms a separate clade [16]. Obviously, each species responsible for human babesiosis forms a monophyletic clade. One reason for our results differing from previous reports is limited phylogenetic information on the single or a few genes used to analyze this relationship. Our results provide robust evidence to resolve the position for this human pathogen (Fig. 3b).

Estimating the dates of speciation across Apicomplexa is a challenging task, as there are no available fossil documents, whereas the increasing amount of apicomplexan parasite genome data enables estimation of divergence time, which was performed using a Generalized Phylogenetic Coalescent Sampler (G-PhoCS) [22]. Babesia duncani and other Babesia spp. infective to bovine and ovine species appear to have split around 351.5 million years ago (Mya). Interestingly, one of the Babesia species, B. microti, derived from a common ancestor with other Piroplasm parasites around 614.2 Mya (Fig. 4). This result is consistent with previous reports that revealed piroplasm parasite speciation events to have been earlier than those of their hosts and vectors [23, 24].

Estimated divergence time across Apicomplexa parasites. Species dates were determined using 310 orthologous groups across 18 Apicomplexa parasites and an outgroup species reference genomes. Three fossil times were included to calibrate the split of these species. Ninety-five percent confidence intervals for each node are shown by heat maps

Babesia duncani species-specific genes

Multigene families are well known to play critical roles and evolve extremely rapidly during species evolution and adaptation to hosts. Completeness of B. duncani genome sequencing facilitates a better understanding of its adaption evolution, vector-pathogen and pathogen-host interactions, and the discovery of virulence factors. For Apicomplexa parasites, most large size of family is species-specific genes, such as fam gene families in Plasmodium gallinaceum and Plasmodium relictum, var genes in P. falciparum, pir genes in P. vivax, and Plasmodium knowlesi, msa in Babesia spp. [25,26,27,28]. Likewise, we identified the largest gene family in B. duncani, containing 89 members that encode a motif conserved across family members, which is a novel family, and is named B. duncani largest family 1 (blf 1, Additional file 2: Table S2) [29,30,31]. Additionally, conserved motifs were identified in this gene family by MEME (Fig. 5) [32, 33]. Sixty-five out of 89 genes each encodes a protein with at least one predicted transmembrane helix, and the remainder of these are predicted to be exported. It is impossible to determine significant sequence similarity to other apicomplexan parasite genomes. Almost all of these genes are located in the subtelomeric region, and subtelomeric multigene families in Plasmodium spp. have been proved to be important for transporting proteins into/through the host cell (Fig. 6) [34]. RNA-Seq data proved that 53 out of 89 members of blf 1 gene family are expressed in blood-stage.

We identify 223 species-specific genes without orthologs in other Babesia spp. and Theileria spp. included in this study, which were distributed across its whole genome (Fig. 6). Thirty-one of these genes present signal peptide, identified by signalp-5.0b (Additional file 3: Table S3), and almost all proteins encoded by these genes are secreted into the host cell environment using TMHMM, suggesting that these genes might involve in parasite and host/vector receptor interactions [35, 36]. Relative synonymous codon usage was estimated by CodonW v1.4.2 program (https://github.com/smsaladi/codonw-slim). No codon usage bias was observed between 223 species-specific genes and all orthologues in B. duncani (Fig. 7). The values of relative synonymous codon usage were tested by paired t test, and no significant difference was observed between species-specific genes and all orthologs (p = 0.997). Aligning with RNA-Seq data of B. duncani, 215 out of 223 B. duncani species-specific genes show evidence of expression in the blood-stage, meaning that the remaining eight genes might play a role in other stages of the life cycle. Ninety-eight of these genes are unlikely to ascribe their potential functions by BLASTP and Interproscan (v5.48-83.0), highlighting that limited efforts have been made to explore the content of genome that may play critical roles relating to host specificity and immune evasion [37, 38]. Species-specific genes may be an alternative source of evolutionary innovations and host adaptations, whereas their precise biological functions remain to be investigated.

Multigene families

Although we observed 46 expanded and 705 contracted gene families involving 61 genes gained and 710 genes lost, except for glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein family (GPI-AP) and serine esterase (SEA) (Fig. 8; Additional file 5: Table S5), almost all of gene families members slightly increased by 1 or 2 copies and decreased by 1 to 2 copies. Compared with B. microti, these expanded and contracted gene families showed no significant difference. These small expansions and contractions may be caused by an artifact of genome sequencing. GPI-APs have been identified in the membranes of apicomplexan, such as P. falciparum, T. gondii, B. bovis, Trypanosoma brucei, and Leishmania donovani [39,40,41]. Some of the GPI-APs that bind to receptors of erythrocytes in B. divergens and B. canis are expressed on the surface of parasite merozoites [42, 43]. Babesia divergens antigen Bd37 is a GPI-AP expressed on the surface of merozoites, which has been used to immunize animals against B. divergens infection [44]. Subsequently, a homologous GPI-AP of B. canis was proved to protect dogs against this parasite infection [45]. These results highlight the feasibility of a more general strategy involving GPI-AP to develop protective vaccines against Babesia spp., including B. duncani [46]. GPI-APs are also an attractive pool of antigens for vaccine and diagnostic test development. Some of the GPI-APs, including BmGPI12 and BmGPI13 in B. microti, and GPI-anchored merozoite surface antigen-1 are highly expressed in red blood cell stages, suggesting their importance for membrane structure or function [47, 48]. BmGPI12 is also a sensitive diagnostic antigen for determining the prevalence of B. microti in affected countries [49, 50]. The performance of GPI-APs against B. duncani infection and in diagnostic assays needs to be investigated. Concerning the six-cysteine gene family in P. falciparum, some members (Pf48/45, Pf230, and Pf47) contribute to parasite fertilization, while PfP52 and PfP36 perform a vital role in sporozoite invasion of hepatocytes [51,52,53,54]. Mosquito stage-specific proteins of the six-cysteine family, such as P25, P28, P230, P48/45, and Pfs47, show significant efficiency in transmission blocking against Plasmodium; meanwhile, six-cysteine A and B emphasize candidates from this family blocking B. bovis transmission in vector ticks [55,56,57,58]. Twenty-three members of this gene family are identified in B. duncani. However, whether these members perform similar roles in B. duncani development and immune response remains largely unknown.

Evolution gene families in Babesia spp. The dynamics of gene family sizes in the genomes of B. microti, B. duncani, B. ovata, B. bigemina, B. bovis, and Babesia sp. xinjiang. Numbers below the branches indicate gene family expansions/contractions, and the numbers above the branches show gene gains/losses

To complete the life cycle of Babesia spp., host cell invasion is initiated with interactions between parasite proteins and host receptors. Thrombospondin-related anonymous proteins (TRAP) contribute to sporozoites of Plasmodium infecting salivary glands/live cells and merozoites of Babesia infecting red blood cells [59, 60]. In some Plasmodium spp., such as P. berghei ANKA and P. vivax P01, a single copy of TRAP was identified in genomes [60]. However, we identified seven copies in B. duncani, revealing that they may contribute to a more sophisticated process in terms of parasite-host interactions. Furthermore, transcriptional evidence of all these genes is found in blood stages, consistent with their role in red blood cell adhesion/invasion.

Babesia duncani adaptive evolution

Using pairwise Ka/Ks comparisons of the B. duncani genome with its closest sister species, we are able to discover species-specific adaptation to vectors or hosts. A branch-site model analysis was performed to determine the positive selection across 1437 orthologous genes that occurred in B. duncani and other piroplasm parasites. Within the B. duncani genome, we identified 38 genes that presented positive selection (Table 2). Furthermore, we determined these positive selection genes to fully examine whether they could perform specific functions in B. duncani life cycle. We noticed that some essential genes received selection pressure and took important roles in cellular process, including in transcription (high mobility group protein B1, AP2 domain transcription factor ap2ix-6, helicase), translation (tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase, RNA methyltransferase, ribosomal protein L24, N6-adenine-specific methylase), post-transcription modification (phosphatase methylesterase, GPI ethanolamine phosphate transferase 3), and protein degradation (peptidase, 26S proteasome, ERAD-associated E3 ubiquitin-ligase, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase, ubiquitin carboxyl-terminal hydrolase).

We also observed positive selection events in some genes correlated with the survival environment of B. duncani. Selection was detected in a gene involved in taking nutrients from red blood cell plasma (heme oxygenase), implying adaptation to the internal environment of red blood cells. Positive selection was also found in genes contributing to maintaining the morphology of B. duncani, including cytoskeleton-associated protein (subpellicular microtubule protein 1) and erythrocyte-binding protein (CD2 antigen cytoplasmic tail-binding 2).

Conclusions

In conclusion, using ONT sequencing and Illumina sequencing technologies, we assembled and generated the first B. duncani reference genome, which is essential to better understand this species’ biological features. We confirmed that B. duncani forms a phylogenetically distinct clade from other Piroplasm parasites and estimated the speciation date of B. duncani that occurred later than that of B. microti, providing new insights into the evolutionary history of B. duncani. Two gene families present significant expansion in B. duncani and may play important roles in host cell invasion and virulence of B. duncani, using comparative genomic analyses. Whether these gene families perform predicted roles needs to be unraveled through genetic manipulation technology and functional studies. Genes identified in B. duncani presenting signal of positive selection perform diverse roles in transcription, translation, and post-translated modification processes. Our study provides basic information for further exploring B. duncani features, such as host-parasite and tick-parasite interactions.

Methods

Sequencing and preparing data

The first case of babesiosis, caused by B. duncani WA1, was reported in a 41-year-old man in Washington state. This parasite was obtained from ATCC (PRA-302™) and injected into hamsters. Sub-cloning of this parasite was not performed, as a continuous culture system in vitro has not been developed in our laboratory. When the parasitemia reached 10%, infected red blood cells were collected and merozoites of B. duncani were purified as previously reported with minor modification [61]. Briefly, host nucleated blood cells were removed using a syringe filter for white blood cells (PALL, USA). Following this, blood cells were washed three times with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH7.4) and lysed by saponin (0.05% in PBS). Merozoites were collected by centrifugation at 10,000g for 30 min.

Genomic DNA was extracted using a commercial DNA extractions kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). The library for PromethION was constructed using a ligation kit (SQK- LSK109, Oxford Nanopore Technology, Oxford, UK) and then analyzed using two FLOMIN106 flow cells (v9.4.1). The raw FAST5 data were base called using Guppy (v3.2.2) [62]. A library of 400-bp paired-end reads of genomic DNA was prepared for genome correction and sequenced using the Illumina sequencing platform. Total RNA was extracted, and library construction was performed according to Illumina TruSeq mRNA library protocol.

De novo assembly

To remove hamster genomic DNA contamination, the NanoLyse software package was used to compare ONT sequencing data with Cricetulus griseus genome (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/; accession number GCA_000223135.1) [63]. Eventually, 11,118 reads (account for 5.7% of ONT data) from host genomic DNA were removed. Low-quality reads, contained in ONT sequencing data, were filtered by NanoFilt [63]. Meanwhile, for Illumina sequencing data, low-quality base/reads and adaptor sequences were removed by trim_galore (https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore) and contamination of host genome DNA (423,726 paired reads account for 4.49% of Illumina sequencing data) was depleted by aligning Illumina reads with Cricetulus griseus genome using bowtie2 [64].

In our previous study, genome assembly pipelines were developed for Piroplasm parasites [65]. Briefly, genome assembly of ONT reads was performed using NECAT (v0.0.1) and Canu (v2.2.2) with default parameters. Correction of raw draft genomes is a critical step in ONT reads assembly (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn, CRA004588; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA844476) [66, 67]. Draft genomes were improved by ONT reads self-correction using Medaka (v1.3.4). Further error correction was an essential step using Illumina data, which are available from the National Genomics Data Center (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn) under accession number CRA004607 and the National Center for Biotechnology Information (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov) under accession number PRJNA844476, using Pilon to generate the final assembly output [66,67,68]. To generate more contiguity assembly, we also merged assembly outputs from assemblies derived from distinct de novo tools (NEACT and Canu) (Fig. 9). Samtools was employed to determine the overall coverage of the genome assembly by mapping Illumina sequencing reads to it. We obtained 98.1% coverage of the assembly. Furthermore, the quality of assembly was evaluated using Benchmarking Universal Single-copy Orthologs (BUSCO v5.1.3) to determine the completeness using the core apicomplexan dataset (apicomplexa_odb10) [20, 69, 70].

The framework of genome assembly. In the stage of assembly, Nanoplot and NanoComp were applied to statistic reads length and quality distribution. Nanofilt and NanoLyse were employed to remove low-quality reads and remove contaminated DNA from host, respectively. Subsequently, each draft genome was corrected using ONT reads and Illumina reads to improve genome accuracy. Finally, genomes generated from NECAT and Canu were merged with the quickmerge software to produce contiguity assembly

Genome annotation

Before genome annotation, repeat sequences were masked to reduce the requirements of computed resources and to produce reliable annotation outcomes. For this purpose, a standard pipeline was performed including (1) simple tandem repeat sequences predicted using TRF (v4.09) program, (2) ab initio repeat identification using RepeatScout (v1.0.5), and (3) homologous alignment using RepeatMasker program [71,72,73]. The genome of masked sequences was performed gene structure annotation.

Gene structures were predicted by a combination of ab initio, homology alignment, and transcriptome data. In terms of ab initio, PASA (v2.3.1) was applied to produce candidate gene structures based on the longest open reading frame and a GFF3 file, which could be applied to obtain a set of gene structured for training gene models of Augustus (v3.3.3) and GlimmerHMM (3.0.4) programs [64, 74,75,76,77]. Following this, we used Augustus and GlimmerHMM to predict the gene structure based on the trained gene models. Furthermore, ATT, exonerate (2.4.0), and GeneID (v1.4.5) programs were used to align with the UniProt apicomplexan database to identify candidate gene structures [78,79,80]. Illumina RNA-Seq reads (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn, CRA004607) were mapped against the B. duncani genome with Tophat2 (v2.1.1) [81]. Mapped reads were processed using Cufflinks (v2.2.1) to generate annotation information as transcriptional prediction data [82,83,84]. The evidence of gene annotation from ab initio, homologous alignments, and transcriptional data was integrated into a non-redundant gene set by EvidenceModeler (v1.1.1) [85].

Collinearity analysis

Three species with completed genomes, including B. duncani (https://www.cncb.ac.cn/, GWHBECJ00000000), B. microti (GCF_000691945.2), and B. bovis (AAXT02000000), were selected for collinearity analysis. MCScanX (https://github.com/tanghaibao/jcvi/wiki/MCscan-(Python-version)) was used to identify homologous scaffolds and gene synteny. The pairwise blocks were defined as at least five homologous genes in the 25-gene size window.

Ortholog group identification and gene family expansion and contraction analysis

Apicomplexan protein sequences were downloaded from NCBI and Plasmo DB databases. The orthologous group across 18 species, including B. duncani (https://www.cncb.ac.cn/, GWHBECJ00000000), B. bigemina (GCA_000981445.1), B. bovis (AAXT02000000), B. microti (GCF_000691945.2), B. ovata (GCA_002897235.1), Babesia sp. Xinjiang (GCA_002095265.1), T. annulata (GCA_000003225.1), T. parva (GCA_000165365.1), T. equi (GCA_000342415.1), T. orientalis (GCA_000740895.1), Toxoplasma gondii (GCA_000006565.2), Neospora caninum (GCA_016097395.1), Plasmodium falciparum (GCA_000002765.3), P. vivax (GCA_000002415.2), P. yoelii (GCA_900002385.2), Cryptosporidium parvum (GCA_000165345.1), Eimeria tenella (GCA_000499545.1), and Tetrahymena thermophila (GCA_000189635.1), were identified using OrthoFinder (v2.5.4), which is a practical, fast, accurate, and comprehensive tool for comparative genomes [86, 87]. The program, based on amino acid sequence alignment, uses diamond, and the important parameter inflation index was set at 1.5 to balance sensitivity and selectivity. Identified ortholog groups were used for further analysis of gene family expansion and contraction with café (v2.0) [88, 89].

Phylogenetic analysis and divergence time estimation

Three hundred ten single-copy orthologous that were present in 18 species of Apicomplexa parasites were aligned with MUSCLE, and ambiguous alignments were processed using Gblocks with default parameters (parameters: -t = p –b = h –p =n –b4 = 2) [90]. Then aligned sequences were concatenated by custom scripts to generate FASTA files for further phylogenetic analysis. The maximum likelihood phylogenetic trees were generated by RAxML with the best fit model LG+F+R5 [91]. ITOL was used to visualize and edit the labels of phylogenetic trees (http://itol2.embl.de/upload.cgi) [92].

The divergence time for Apicomplexa parasites was estimated using the mcmctree program with three correlated time points, 817 million years ago (Mya, divergence time between T. gondii and P. falciparum, ranging from 580 to 817 Mya), 470 Mya (divergence time between E. tenella and N. caninum), and 1290 Mya (divergence time between C. parvum and T. thermophila, ranging from 767 to 1344 Mya) [93,94,95,96,97].

Ka/Ks analysis

The nonsynonymous (Ka) and synonymous (Ks) substitution rates and positive selection strength (Ka/Ks) were calculated by KaKs_Calculator (v2.0) [98]. First, reciprocal BLAST was used to run the pairwise alignments between Babesia spp., the e-value was set to 10−5, and the number of hits for each pair of species was set to 5. Second, each pairwise protein sequence was aligned by MUSCLE, and pairwise nucleotide sequence alignments were generated by transforming protein alignments into codon alignments with ParaAT [99]. Third, Ka/Ks ratios were calculated based on pairwise codon alignments using KaKs_Calculator, and the models of KaKs_Calculator were invoked from PAML. M0 model (Branch site model) was used in this study [100].

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the article, its supplementary information files are publicly available in repositories. The genomic sequencing data of ONT reads and Illumina reads presented in this study have been deposited in the China National Center for Bioinformation (https://www.cncb.ac.cn/; CRA004588 and CRA004607) and the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under project accession number PRJNA844476 [66, 67]. The RNA-seq data have also been deposited in the China National Center for Bioinformation (CRA004607) and the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) database under project accession number PRJNA84447 [66, 67].

Abbreviations

- ONT:

-

Oxford Nanopore Technology

- ITS:

-

Internal transcribed spacer

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- CoxI :

-

Coxidase subunit I

- Cob :

-

Cytochrome b

- blf 1:

-

B. duncani largest family 1

- TRAP:

-

Thrombospondin-related anonymous protein

- GPI-AP:

-

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein family

- SEA:

-

Serine esterase

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- Ka:

-

Nonsynonymous

- Ks:

-

Synonymous

References

Kim JY, Cho SH, Joo HN, Tsuji M, Cho SR, Park IJ, et al. First case of human babesiosis in Korea: detection and characterization of a novel type of Babesia sp. (KO1) similar to ovine Babesia. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45(6):2084–7.

Shih CM, Liu LP, Chung WC, Ong SJ, Wang CC. Human babesiosis in Taiwan: asymptomatic infection with a Babesia microti-like organism in a Taiwanese woman. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35(2):450–4.

Man SQ, Qiao K, Cui J, Feng M, Fu YF, Cheng XJ. A case of human infection with a novel Babesia species in China. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5:28.

Gonzalez LM, Castro E, Lobo CA, Richart A, Ramiro R, Gonzalez-Camacho F, et al. First report of Babesia divergens infection in an HIV patient. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;33:202–4.

Jia N, Zheng YC, Jiang JF, Jiang RR, Jiang BG, Wei R, et al. Human babesiosis caused by a Babesia crassa-like pathogen: a case series. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67(7):1110–9.

Wang J, Zhang S, Yang J, Liu J, Zhang D, Li Y, et al. Babesia divergens in human in Gansu province, China. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2019;8(1):959–61.

Kjemtrup AM, Conrad PA. Human babesiosis: an emerging tick-borne disease. Int J Parasitol. 2000;30(12-13):1323–37.

Vannier EG, Diuk-Wasser MA, Ben Mamoun C, Krause PJ. Babesiosis. Infect Dis Clin N Am. 2015;29(2):357–70.

Ord RL, Lobo CA. Human babesiosis: pathogens, prevalence, diagnosis and treatment. Curr Clin Microbiol Rep. 2015;2(4):173–81.

Dao AH, Eberhard ML. Pathology of acute fatal babesiosis in hamsters experimentally infected with the WA-1 strain of Babesia. Lab Investig. 1996;74(5):853–9.

Moro MH, David CS, Magera JM, Wettstein PJ, Barthold SW, Persing DH. Differential effects of infection with a Babesia-like piroplasm, WA1, in inbred mice. Infect Immun. 1998;66(2):492–8.

Quick RE, Herwaldt BL, Thomford JW, Garnett ME, Eberhard ML, Wilson M, et al. Babesiosis in Washington state: a new species of Babesia? Ann Intern Med. 1993;119(4):284–90.

Herwaldt BL, Kjemtrup AM, Conrad PA, Barnes RC, Wilson M, McCarthy MG, et al. Transfusion-transmitted babesiosis in Washington state: first reported case caused by a WA1-type parasite. J Infect Dis. 1997;175(5):1259–62.

Scott JD, Scott CM. Human babesiosis caused by Babesia duncani has widespread distribution across Canada. Healthcare-Basel. 2018;6(2):49.

Conrad PA, Kjemtrup AM, Carreno RA, Thomford J, Wainwright K, Eberhard M, et al. Description of Babesia duncani n.sp (Apicomplexa: Babesiidae) from humans and its differentiation from other piroplasms. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36(7):779–89.

Virji AZ, Thekkiniath J, Ma WX, Lawres L, Knight J, Swei A, et al. Insights into the evolution and drug susceptibility of Babesia duncani from the sequence of its mitochondrial and apicoplast genomes. Int J Parasitol. 2019;49(2):105–13.

Schnittger L, Rodriguez AE, Florin-Christensen M, Morrison DA. Babesia: a world emerging. Infect Genet Evol. 2012;12(8):1788–809.

Jalovecka M, Sojka D, Ascencio M, Schnittger L. Babesia life cycle - when phylogeny meets biology. Trends Parasitol. 2019;35(5):356–68.

Marcais G, Kingsford C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(6):764–70.

Manni M, Berkeley MR, Seppey M, Simao FA, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO update: novel and streamlined workflows along with broader and deeper phylogenetic coverage for scoring of eukaryotic, prokaryotic, and viral genomes. Mol Biol Evol. 2021;38(10):4647–54.

Guan GQ, Korhonen PK, Young ND, Koehler AV, Wang T, Li YQ, et al. Genomic resources for a unique, low-virulence Babesia taxon from China. Parasite Vector. 2016;9:564.

Gronau I, Hubisz MJ, Gulko B, Danko CG, Siepel A. Bayesian inference of ancient human demography from individual genome sequences. Nat Genet. 2011;43(10):1031–4.

Douzery EJ, Snell EA, Bapteste E, Delsuc F, Philippe H. The timing of eukaryotic evolution: does a relaxed molecular clock reconcile proteins and fossils? Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(43):15386–91.

Parfrey LW, Lahr DJ, Knoll AH, Katz LA. Estimating the timing of early eukaryotic diversification with multigene molecular clocks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(33):13624–9.

Su XZ, Heatwole VM, Wertheimer SP, Guinet F, Herrfeldt JA, Peterson DS, et al. The large diverse gene family var encodes proteins involved in cytoadherence and antigenic variation of Plasmodium falciparum infected erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82(1):89–100.

Otto TD, Bohme U, Jackson AP, Hunt M, Franke-Fayard B, Hoeijmakers WAM, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of rodent malaria parasite genomes and gene expression. BMC Biol. 2014;12:86.

Otto TD, Rayner JC, Bohme U, Pain A, Spottiswoode N, Sanders M, et al. Genome sequencing of chimpanzee malaria parasites reveals possible pathways of adaptation to human hosts. Nat Commun. 2014;5:4754.

Brayton KA, Lau AOT, Herndon DR, Hannick L, Kappmeyer LS, Berens SJ, et al. Genome sequence of Babesia bovis and comparative analysis of apicomplexan hemoprotozoa. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(10):1401–13.

Bailey TL, Boden M, Buske FA, Frith M, Grant CE, Clementi L, et al. MEME SUITE: tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Web Server issue):W202–8.

Carlton JM, Angiuoli SV, Suh BB, Kooij TW, Pertea M, Silva JC, et al. Genome sequence and comparative analysis of the model rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium yoelii. Nature. 2002;419(6906):512–9.

Neafsey DE, Galinsky K, Jiang RH, Young L, Sykes SM, Saif S, et al. The malaria parasite Plasmodium vivax exhibits greater genetic diversity than Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Genet. 2012;44(9):1046–50.

Bailey TL, Johnson J, Grant CE, Noble WS. The MEME Suite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(W1):W39–49.

Bailey TL, Elkan C. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1994;2:28–36.

Marti M, Good RT, Rug M, Knuepfer E, Cowman AF. Targeting malaria virulence and remodeling proteins to the host erythrocyte. Science. 2004;306(5703):1930–3.

Krogh A, Larsson B, von Heijne G, Sonnhammer ELL. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: application to complete genomes. J Mol Biol. 2001;305(3):567–80.

Sonnhammer EL, von Heijne G, Krogh A. A hidden Markov model for predicting transmembrane helices in protein sequences. Proc Int Conf Intell Syst Mol Biol. 1998;6:175–82.

Quevillon E, Silventoinen V, Pillai S, Harte N, Mulder N, Apweiler R, et al. InterProScan: protein domains identifier. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):W116–20.

Zdobnov EM, Apweiler R. InterProScan - an integration platform for the signature-recognition methods in InterPro. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(9):847–8.

Smith TK, Sharma DK, Crossman A, Dix A, Brimacombe JS, Ferguson MAJ. Parasite and mammalian GPI biosynthetic pathways can be distinguished using synthetic substrate analogues. EMBO J. 1997;16(22):6667–75.

Ferguson MAJ. The structure, biosynthesis and functions of glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchors, and the contributions of trypanosome research. J Cell Sci. 1999;112(17):2799–809.

Rodriguez AE, Couto A, Echaide I, Schnittger L, Florin-Christensen M. Babesia bovis contains an abundant parasite-specific protein-free glycerophosphatidylinositol and the genes predicted for its assembly. Vet Parasitol. 2010;167(2-4):227–35.

Delbecq S, Auguin D, Yang YS, Loehr F, Arold S, Schetters T, et al. The solution structure of the adhesion protein Bd37 from Babesia divergens reveals structural homology with eukaryotic proteins involved in membrane trafficking. J Mol Biol. 2008;375(2):409–24.

Yang YS, Murciano B, Moubri K, Cibrelus P, Schetters T, Gorenflot A, et al. Structural and functional characterization of Bc28.1, major erythrocyte-binding protein from Babesia canis merozoite surface. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(12):9495–508.

Hadj-Kaddour K, Carcy B, Vallet A, Randazzo S, Delbecq S, Kleuskens J, et al. Recombinant protein Bd37 protected gerbils against heterologous challenges with isolates of Babesia divergens polymorphic for the bd37 gene. Parasitology. 2007;134:187–96.

Moubri K, Kleuskens J, Van de Crommert J, Scholtes N, Van Kasteren T, Delbecq S, et al. Discovery of a recombinant Babesia canis supernatant antigen that protects dogs against virulent challenge infection. Vet Parasitol. 2018;249:21–9.

Wieser SN, Schnittger L, Florin-Christensen M, Delbecq S, Schetters T. Vaccination against babesiosis using recombinant GPI-anchored proteins. Int J Parasitol. 2019;49(2):175–81.

Silva JC, Cornillot E, McCracken C, Usmani-Brown S, Dwivedi A, Ifeonu OO, et al. Genome-wide diversity and gene expression profiling of Babesia microti isolates identify polymorphic genes that mediate host-pathogen interactions. Sci Rep. 2016;6:35284.

Pedroni MJ, Sondgeroth KS, Gallego-Lopez GM, Echaide I, Lau AOT. Comparative transcriptome analysis of geographically distinct virulent and attenuated Babesia bovis strains reveals similar gene expression changes through attenuation. BMC Genomics. 2013;14:763.

Cheng K, Coller KE, Marohnic CC, Pfeiffer ZA, Fino JR, Elsing RR, et al. Performance evaluation of a prototype architect antibody assay for Babesia microti. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56(8):e00460–18.

Cornillot E, Dassouli A, Pachikara N, Lawres L, Renard I, Francois C, et al. A targeted immunomic approach identifies diagnostic antigens in the human pathogen Babesia microti. Transfusion. 2016;56(8):2085–99.

Arredondo SA, Kappe SHI. The s48/45 six-cysteine proteins: mediators of interaction throughout the Plasmodium life cycle. Int J Parasitol. 2017;47(7):409–23.

Anthony TG, Polley SD, Vogler AP, Conway DJ. Evidence of non-neutral polymorphism in Plasmodium falciparum gamete surface protein genes Pfs47 and Pfs48/45. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2007;156(2):117–23.

VanBuskirk KM, O’Neill MT, De La Vega P, Maier AG, Krzych U, Williams J, et al. Preerythrocytic, live-attenuated Plasmodium falciparum vaccine candidates by design. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(31):13004–9.

van Dijk MR, van Schaijk BCL, Khan SM, van Dooren MW, Ramesar J, Kaczanowski S, et al. Three members of the 6-cys protein family of Plasmodium play a role in gamete fertility. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(4):e1000853.

Alzan HF, Bastos RG, Ueti MW, Laughery JM, Rathinasamy VA, Cooke BM, et al. Assessment of Babesia bovis 6cys A and 6cys B as components of transmission blocking vaccines for babesiosis. Parasit Vectors. 2021;14(1):210.

Acquah FK, Adjah J, Williamson KC, Amoah LE. Transmission-blocking vaccines: old friends and new prospects. Infect Immun. 2019;87(6):e00775–18.

Saul A. Mosquito stage, transmission blocking vaccines for malaria. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20(5):476–81.

Ishino T, Chinzei Y, Yuda M. Two proteins with 6-cys motifs are required for malarial parasites to commit to infection of the hepatocyte. Mol Microbiol. 2005;58(5):1264–75.

Gaffar FR, Yatsuda AP, Franssen FFJ, de Vries E. A Babesia bovis merozoite protein with a domain architecture highly similar to the thrombospondin-related anonymous protein (TRAP) present in Plasmodium sporozoites. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 2004;136(1):25–34.

Aunin E, Bohme U, Sanderson T, Simons ND, Goldberg TL, Ting N, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic evidence for descent from Plasmodium and loss of blood schizogony in Hepatocystis parasites from naturally infected red colobus monkeys. PLoS Pathog. 2020;16(8):e1008717.

Guan GQ, Moreau E, Liu JL, Ma ML, Rogniaux H, Liu AH, et al. BQP35 is a novel member of the intrinsically unstructured protein (IUP) family which is a potential antigen for the sero-diagnosis of Babesia sp. BQ1 (Lintan) infection. Vet Parasitol. 2012;187(3-4):421–30.

Wick RR, Judd LM, Holt KE. Performance of neural network basecalling tools for Oxford Nanopore sequencing. Genome Biol. 2019;20:129.

De Coster W, D’Hert S, Schultz DT, Cruts M, Van Broeckhoven C. NanoPack: visualizing and processing long-read sequencing data. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(15):2666–9.

Langmead B, Salzberg SL. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods. 2012;9(4):357–9.

Wang J, Chen K, Ren Q, Zhang Y, Liu J, Wang G, et al. Systematic comparison of the performances of de novo genome assemblers for Oxford Nanopore Technology reads from Piroplasm. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:696669.

Wang J, Guan G, Yin H, Luo J. Babesia duncani genome. China National Center for Bioinformation. 2021. https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/21837/show.

Wang J, Guan G, Yin H, Luo J. Babesia duncani genome sequencing and assembly. NCBI. 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA844476.

Hu J, Fan J, Sun Z, Liu S. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics. 2020;36(7):2253–5.

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(14):1754–60.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, et al. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(16):2078–9.

Benson G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999;27(2):573–80.

Price AL, Jones NC, Pevzner PA. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:I351–8.

Flynn JM, Hubley R, Goubert C, Rosen J, Clark AG, Feschotte C, et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(17):9451–7.

Haas BJ, Delcher AL, Mount SM, Wortman JR, Smith RK, Hannick LI, et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(19):5654–66.

Stanke M, Tzvetkova A, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS at EGASP: using EST, protein and genomic alignments for improved gene prediction in the human genome. Genome Biol. 2006;7(Suppl:1):S11.1-8.

Stanke M, Morgenstern B. AUGUSTUS: a web server for gene prediction in eukaryotes that allows user-defined constraints. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33(Web Server issue):w465–7.

Majoros WH, Pertea M, Salzberg SL. TigrScan and GlimmerHMM: two open source ab initio eukaryotic gene-finders. Bioinformatics. 2004;20(16):2878–9.

Huang XQ, Adams MD, Zhou H, Kerlavage AR. A tool for analyzing and annotating genomic sequences. Genomics. 1997;46(1):37–45.

Slater GS, Birney E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. Bmc Bioinformatics. 2005;6:31.

Parra G, Blanco E, Guigo R. GeneID in Drosophila. Genome Res. 2000;10(4):511–5.

Kim D, Pertea G, Trapnell C, Pimentel H, Kelley R, Salzberg SL. TopHat2: accurate alignment of transcriptomes in the presence of insertions, deletions and gene fusions. Genome Biol. 2013;14(4):R36.

Trapnell C, Hendrickson DG, Sauvageau M, Goff L, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential analysis of gene regulation at transcript resolution with RNA-seq. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31(1):46–53.

Roberts A, Pimentel H, Trapnell C, Pachter L. Identification of novel transcripts in annotated genomes using RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2011;27(17):2325–9.

Roberts A, Trapnell C, Donaghey J, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Improving RNA-Seq expression estimates by correcting for fragment bias. Genome Biol. 2011;12(3):R22.

Haas BJ, Salzberg SL, Zhu W, Pertea M, Allen JE, Orvis J, et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 2008;9(1):R7.

Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 2019;20(1):238.

Emms DM, Kelly S. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015;16(1):157.

Han MV, Thomas GWC, Lugo-Martinez J, Hahn MW. Estimating gene gain and loss rates in the presence of error in genome assembly and annotation using CAFE 3. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(8):1987–97.

Hahn MW, De Bie T, Stajich JE, Nguyen C, Cristianini N. Estimating the tempo and mode of gene family evolution from comparative genomic data. Genome Res. 2005;15(8):1153–60.

Talavera G, Castresana J. Improvement of phylogenies after removing divergent and ambiguously aligned blocks from protein sequence alignments. Syst Biol. 2007;56(4):564–77.

Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–3.

Letunic I, Bork P. Interactive Tree Of Life (iTOL) v4: recent updates and new developments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W256–9.

dos Reis M, Donoghue PCJ, Yang ZH. Bayesian molecular clock dating of species divergences in the genomics era. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(2):71–80.

Yang ZH, Rannala B. Bayesian estimation of species divergence times under a molecular clock using multiple fossil calibrations with soft bounds. Mol Biol Evol. 2006;23(1):212–26.

dos Reis M, Yang ZH. Approximate likelihood calculation on a phylogeny for bayesian estimation of divergence times. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28(7):2161–72.

Gilabert A, Otto TD, Rutledge GG, Franzon B, Ollomo B, Arnathau C, et al. Plasmodium vivax-like genome sequences shed new insights into Plasmodium vivax biology and evolution. PLoS Biol. 2018;16(8):e2006035.

Otto TD, Gilabert A, Crellen T, Bohme U, Arnathau C, Sanders M, et al. Genomes of all known members of a Plasmodium subgenus reveal paths to virulent human malaria. Nat Microbiol. 2018;3(6):687–97.

Wang D, Zhang Y, Zhang Z, Zhu J, Yu J. KaKs_Calculator 2.0. a toolkit incorporating gamma-series methods and sliding window strategies. Genomics Proteomics Bioinform. 2010;8(1):77–80.

Zhang Z, Xiao J, Wu J, Zhang H, Liu G, Wang X, et al. ParaAT. a parallel tool for constructing multiple protein-coding DNA alignments. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;419(4):779–81.

Di Maro A, Citores L, Russo R, Iglesias R, Ferreras JM. Sequence comparison and phylogenetic analysis by the maximum likelihood method of ribosome-inactivating proteins from angiosperms. Plant Mol Biol. 2014;85(6):575–88.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Jianming Zeng (University of Macau), and all members of his bioinformatics team and Biotrainee for sharing their experience and codes. The use of the biorstudio high performance computing cluster (https://biorstudio.cloud) at Biotrainee and the Shanghai HS Biotach Co.,Ltd for conducting the research reported in this paper. We also thank Dr. Haoyu Chao (Zhejiang University) for sharing the codes.

Funding

This study was financially supported by the NSFC (№31972701), ASTIP (CAAS-ASTIP-2016-LVRI), NBCIS (CARS-37), the National Parasitic Resources Center (NPRC-2019-194-30), the Leading Fund of Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute (LVRI-SZJJ-202105), and the hatching program of SKLVEB (SKLVEB2021CGQD02).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Manuscript: JW and KC. Analysis: JW, KC, and GW. Reagents/materials: JY, SZ, JX, YL, and GL. Supervision: JL, YH, and GG. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The collection and manipulation of sheep blood samples were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Lanzhou Veterinary Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences. All sampling procedures were handled in accordance with the Animal Ethics Procedures and Guidelines of the People’s Republic of China (Permit No. LVRIAEC-2018-001). All the procedures conducted were according to the Ethical Procedures and Guidelines of the People’s Republic of China.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1

. Protein annotations of B. duncani using BLASTP and Interproscan programs.

Additional file 2: Table S2

. Babesia duncani largest gene family 1.

Additional file 3: Table S3

. 223 species specific genes in B. duncani.

Additional file 4: Table S4

. Multi-gene families in B. duncani.

Additional file 5: Table S5

. Significantly expanded gene families in B. duncani.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Chen, K., Yang, J. et al. Comparative genomic analysis of Babesia duncani responsible for human babesiosis. BMC Biol 20, 153 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-022-01361-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12915-022-01361-9