Abstract

Background

In Canada, primary care reforms led to the implementation of various team-based care models to improve access and provide more comprehensive care for patients. Despite these advances, ongoing challenges remain. The aim of this scoping review is to explore current understanding of the functioning of these care models as well as the contexts in which they have emerged and their impact on the population, providers and healthcare costs.

Methods

The Medline and CINAHL databases were consulted. To be included, team-based care models had to be co-located, involve a family physician, specify the other professionals included, and provide information about their organization, their relevance and their impact within a primary care context. Models based on inter-professional intervention programs were excluded. The organization and coordination of services, the emerging contexts and the impact on the population, providers and healthcare costs were analysed.

Results

A total of 5952 studies were screened after removing duplicates; 15 articles were selected for final analysis. There was considerable variation in the information available as well as the terms used to describe the models. They are operationalized in various ways, generally consistent with the Patient’s Medical Home vision. Except for nurses, the inclusion of other types of professionals is variable and tends to be associated with the specific nature of the services offered. The models primarily focus on individuals with mental health conditions and chronic diseases. They appear to generally satisfy the expectations of the overarching framework of a high-performing team-based primary care model at patient and provider levels. However, economic factors are seldom integrated in their evaluations.

Conclusions

The studies rarely provide an overarching view that permits an understanding of the specific contexts, service organization, their impacts, and the broader context of implementation, making it difficult to establish universal guidelines for the operationalization of effective models. Negotiating the inherent complexity associated with implementing models requires a collaborative approach between various stakeholders, including patients, to tailor the models to the specific needs and characteristics of populations in given areas, and reflection about the professionals to be included in delivering these services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Primary care is defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as a “model of care that supports first-contact, accessible, continuous, comprehensive, and coordinated person-focused care” [1]. A model of care is a conceptualization and operationalization of how services are delivered, encompassing care processes, organization of providers, management of services and enabling factors to support their development [2]. Primary care serves as an accessible entry point for healthcare, providing ongoing care for patients. Primary care also emphasizes prevention and intersectoral collaboration, allowing consideration of the social determinants of health to provide comprehensive treatment [3].

In Canada, primary care services are mostly provided by family physicians and nurse practitioners in family physician clinics, walk-in clinics or privately funded services (e.g., insurer-paid) [4]. Primary care providers detect and treat common health issues, monitor chronic diseases, and as necessary, refer patients to medical specialists and other healthcare services [4]. In the early 2000s, reforms in primary care were implemented to enhance access to quality healthcare. According to the Quintuple Aim, the indicators of quality healthcare include improving patient experience, population health and healthcare provider satisfaction, reducing healthcare costs, and ensuring health equity [3, 4]. The Canadian reforms aimed to provide integrated care, facilitate access to psychosocial services, prioritize prevention programs, and address the management of chronic diseases [3, 5, 6]. In 2004, the federal ministry of health set a goal that by 2011, 50% of Canadians should have 24/7 access to a multidisciplinary primary health care team [7]. This objective led to the emergence of various primary care groups and networks, for example, the Groupes de médecine familiale (Family Medicine Groups, FMG) in the province of Quebec and the Family Health Teams (FHT) in the province of Ontario [3]. These models are considered co-located team-based primary care models; that is, an interprofessional team collaborates with family physicians in the same location, regardless of the services provided (e.g., mental health care, medical care). These models require the optimization of professional roles so that the right care is delivered by the appropriate professional according to their expertise [8, 9]. Optimizing professional roles means that professionals mobilize their expertise to a greater extent consistent with their respective scope of practice [9, 10]. Role optimization relies on strong interprofessional collaboration within the team to provide effective and comprehensive care [11]. Models of care resulting from the primary care reform, such as the FMG or FHT, were anchored in the Patient’s Medical Home (PMH) vision, which focuses on delivering quality care to patients throughout their lives [12]. In this vision, the family physician plays a central role as the principal primary care provider. To ensure the successful functioning of the model consistent with this vision and the accessibility of care, an interprofessional team working in the same physical space with optimized professional roles collaborates with family physicians to support them in providing prevention and health promotion, psychosocial services and chronic disease management to the general population. The patient can consult an appropriate professional, even if it's not their family physician, as collaboration and communication within the team keep the family physician involved as needed, ensuring effective care coordination. Other models based on interprofessional collaboration exist. However, these models tend to be coordinated intervention programs designed to deal with specific problems in certain primary care settings, for example, a program for people with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [13] or an intervention for depression, diabetes or cardiovascular diseases [14]. These interprofessional interventions differ from the regular services offered in FMGs, possibly cutting across several primary care settings, albeit still requiring collaboration with family physicians.

Although FMGs and FHTs represent examples of significant advancements in the evolution of Canadian primary care services, including their alignment with the PMH perspective, further progress is required, as the initial objectives of these models have not been entirely achieved. For example, with respect to FMGs, a considerable proportion of the population in Quebec still lacks access to a family physician, hospital emergency departments are not adequately relieved of congestion, and access to psychosocial services remains limited [15]. Given these ongoing challenges, it is important to better understand innovative co-located primary care team-based models to identify what is effective, with a view to identifying elements that will contribute towards better meeting the needs of the populations in Quebec, in other Canadian jurisdictions, and elsewhere.

Some reviews have been published that deepen the understanding of primary care models that involve different forms of co-located team-based care [16,17,18,19]; some promising results have emerged. For example, Norful and colleagues [19] demonstrated that there is a significantly better adherence to recommended care guidelines within models where there is co-management between nurse practitioners (NPs) and physicians. A reduction in health services utilization (e.g., emergency room visits) has been demonstrated in some investigations when patients are managed within team-based care models [17, 18]. Despite the usefulness of these findings, these reviews generally focus on a single dimension of the models. When the focus is on an organisational model for a given population, the results tend to concern population health outcomes [16, 18], and more rarely economic outcomes [17], and do not describe how each model works, which makes it difficult to reproduce them. Conversely, when the research focuses more specifically on how the model functions with respect to interprofessional collaboration [20] or on the context in which the models are implemented [21], the evaluation of the impact of these models on the population and healthcare is rarely included, which makes it difficult to assess their performance. Longhini and colleagues’ [22] review adopted a more integrated approach by presenting elements of the functioning of the different models of care identified and the impact on the population and healthcare. However, this review’s findings are limited to people with chronic illnesses, and do not provide information on the contexts in which the models are implemented.

Thus, the existing reviews have rarely provided an integrated overview of the composition of teams, the organization of the model of care, details of the context in which the model of care was implemented, and the impact on the population, professionals and the economy of the healthcare system. To facilitate the development and improvement of team-based care models, it is essential to have a better understanding of the functioning of these models and to have an overall vision that considers the inherent complexity of how these models work. Consistent with our earlier definition of model of care [2], functioning refers to the selection and organization of services (e.g., care processes, type of providers), the management of services, and enabling factors (e.g., financing, resources, system to support collaboration and improve quality).

In this article we report the findings of a scoping review of the studies that have examined the functioning of co-located team-based primary care models in their specific contexts. This review includes three sub-objectives:

-

1.

Identify how these co-located models are operationalized within environments with respect to service organization and coordination;

-

2.

Identify in response to which needs and/or in which contexts these models have emerged;

-

3.

Identify the impact of these models on the population, providers and healthcare costs.

Methods

We chose to carry out a scoping review because this approach permits the development of a portrait of the literature on a relatively vast subject [23], which is relevant given our goal of obtaining an overview of existing co-located team based primary care models, without restricting ourselves to a specific population or a particular context. We adhered to Arksey and O’Malley’s [23] guidelines in conjunction with Levac and colleagues’ [24] approach to guide this scoping review, which follows five steps: (1) identify the research question; (2) identify relevant studies; (3) select study by specifying inclusion and exclusion criteria; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing and reporting the results.

Identifying the research question

The research question that guided this scoping review is as follows: How do co-located primary care models based on interprofessional collaboration function in their specific context?

Identifying relevant studies and study selection

Our initial search was conducted in May 2022, and was subsequently updated in October 2023. Consistent with the socio-medical nature of our research question, we searched the MEDLINE and CINAHL databases, which cover health and other topics related to health care disciplines. We used the following three main keywords, including their variations and the appropriate thesaurus for each database, in English, to identify relevant studies: 'primary care,' 'interprofessional collaboration’, 'model '.

We focused on the concept of interprofessional collaboration, as this concept is broader than role optimization, with the latter relying on interprofessional collaborative practices. The addition of the concept model was made with a focus on models of care and to exclude intervention programs as well as the sole description of interprofessional collaborative practices. This search strategy was reviewed by a librarian, who informed us about the variability of terms and their meanings in the literature, thus increasing the precision of our search strategy and better ensuring that we captured all potentially relevant articles. The detailed search strategy used for MEDLINE (conducted in EBSCOhost) is available in Table 1.

Two reviewers conducted the initial screening (reviewing titles and abstracts) based on inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in the next section. Subsequently, the selected articles were read integrally. To ensure rigour in this process, the two reviewers independently performed both screenings and subsequently consulted with each other to reach a consensus about the articles to be included. In case of any impasse, a third reviewer was involved. Because of the variability of the concepts’ definitions used in the articles, the three reviewers met regularly to ensure a common understanding of each article. During the screening, it was necessary to refine the inclusion and exclusion criteria due to several nuances encountered in our readings. Two additional researchers were consulted as needed to verify the analysis of the selected articles given the complexity of the subject.

Selecting inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied: (1) Empirical research that evaluated a primary care team-based model; we excluded research protocols and literature reviews. (2) The co-located team-based model had to be operationalized in a primary care context; any articles focused on, for example, hospital settings were excluded. (3) Given our interest in models of care involving the integration of healthcare professionals co-located with family physicians to support primary care provision, models based on inter-professional intervention programs across several primary care settings were excluded. (4) An interprofessional team utilizing the co-located collaboration model had to be in operation within the care setting. (5) Because our interest lies in models similar to FMGs and FHTs that rely on the collaboration and the optimization of roles between a family physician and other professionals, the team had to include a family physician, and the articles had to clarify the types of professionals present. (6) The studies had to include assessment of the impact of the models on the population, professionals and/or costs for the healthcare system. In this regard, articles that solely described collaboration dynamics, interprofessional collaboration skills, and the introduction of a new professional, were not included. (7) Consistent with our focus on the Canadian context, we only included studies conducted in countries with a predominantly Western culture (e.g., Western Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand) given their greater potential applicability to this context. (8) Studies were published since 2000, based on the relatively recent evolution in primary care models. (9) Studies were published in English or French, given the authors’ mastery of both languages.

Charting the data

We conducted an initial data extraction by charting the selected articles to identify key elements relevant to our research objectives. First, we highlighted the practice setting to understand the type of primary care organization (e.g., family medicine clinic, community center). Subsequently, to understand how the models are operationalized with respect to the organization and coordination of services (Objective 1), keeping in mind our interest in optimizing professional roles, we extracted information relating to: the type of professionals present in each of the teams; the principle orientation of the services offered (e.g., mental health, chronic illness); the access methods to these professionals and the patient's trajectory in the setting; the systems used to support collaboration and communication (e.g., use of a shared electronic medical record, patient registry, interprofessional meetings) and the type of management. This data will help to document the selection, organization and management of services, especially regarding interprofessional team-based organization [2]. Communication, which is supported by the use of technology, is an essential part of team-based organization [25]. We also identified the model of care approach, as described by the authors; this approach refers to the overall vision that underpins the design and delivery of healthcare services based on patient needs and clinical best practices [26]. Subsequently, we created a category to collect data regarding the contexts in which these models emerged (Objective 2). Specifically, we extracted data related to the socio-professional context, the socio-demographic characteristics of the population in the target area, and the nature and origin of the support received for the model's operation (e.g., provincial funding, a local initiative supported by the city). Understanding local contexts and identifying the specific enabling factors within them permits a clearer comprehension of how these models were adapted to meet local needs, opportunities, and constraints [27]. We also identified the methodology used in each selected article, including objectives, data collection methods, and sample characteristics. Last, we extracted the main results of the studies documenting the impact of the models on the population, professionals and costs for the healthcare system (Objective 3).

Collating, summarizing and reporting the results

Two reviewers independently created summaries of the gathered information and subsequently compared their respective versions to reach a consensus, ensuring the quality of the retained data. In case of any conflicts, a third person helped resolve the impasse. This process made it possible to synthesize the considerable volume of information extracted and standardize the presentation of the data so that it could be compared. We reported the results according to our three sub-objectives, that is: (1) information that provides a clearer understanding of the organization and coordination of services; (2) information relating to the contexts with the aim of understanding the characteristics of the sector in which the models were implemented and the factors that led to their development; (3) the results relating to the impact of the model and the methodological aspects of the research, in order to make sense of these results.

Results

Description

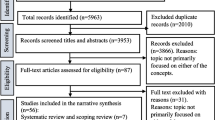

A total of 5952 studies were screened following the removal of duplicates. Subsequently, 5420 studies were excluded following title and abstract screening, leaving 532 articles requiring full text screening. Following the exclusion of 517 documents, 15 were included in the scoping review. The detailed selection process, including the reasons for exclusion, is shown in Fig. 1. The significant reduction is explained by the fact that most team-based models are coordinated intervention programs designed to treat specific problems (e.g., diabetes, Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, depressive symptoms, dementia) rather than models of care based on the provision by co-located interprofessional teams of services for a range of conditions (see “Limitations of the study” for further details). Moreover, there was considerable variability regarding the definition of the concept of team, team-based care model, interprofessional teams or integrated care. The team-based models reported have been implemented mostly in the United-States and Canada (13/15; 86,7%).

Model of care approach

Nearly all the studies referred to the model of care approach upon which the practice was implemented in their settings. In Table 2, these approaches are presented using the study authors’ definitions provided in their article. When the underlying approach was developed by other authors, the reference is indicated in the first column. In this case, the original definition was provided. Although not consistently stated explicitly by the authors, in all team-based models, complementary services and primary care are delivered in the same location [8]. Across the studies, there was considerable variability in the approaches used and how they were defined. This variability reflects different ways of organizing services. For example, multiple variations of a collaborative care model have been presented. Among these variations, one approach highlights the integration of a care manager [28], another the development of the nurse practitioner role [29], while another emphasizes the nature of interprofessional collaboration [30]. The most cited approach is the Canadian shared-care model (3/15; 20%) designed by Kates and colleagues [31].

Organization and coordination of services in the co-located team-based model

To better illustrate how these approaches are operationalized within service organization and coordination, Table 3 presents, in each column: the principle orientation of services; practice context; team composition; which professional is the first entry point for accessing complementary services, service trajectories, and tools to support interprofessional collaboration within the team-based models. To improve the readability and comparability of the information, each column contains a list of possible options revealed during the results collation stage; more than one option could be selected in accordance with the information presented in the article. When the item did not present any information relating to the category presented in the column, the not specified box was checked.

Although all models were situated in a primary care context, seven of these (7/15; 46,7%) were implemented in family medical practices similar to a FMG or a FHT. Two models were community-oriented, for example, the community primary healthcare in Nova Scotia, which provided health promotion activities and programs in a family medical practice but also in other community settings (e.g., outreach programs) [29]. The most common service orientation was for people with mental health conditions (10/15; 66,7%) and chronic disease (6/15; 40%). Some models provided services directed to young people or older adults. In mental health, teams are mainly staffed by family physician, nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers [28, 30, 32,33,34,35,36]. For chronic diseases, teams generally comprise family physicians, nurses (RN, NP or nurse coordinator) [29, 37,38,39] and medical assistants [29, 37,38,39,40]. An exception is Scanlon and colleagues’ [39] model, which includes a social worker. Only the three Ontario (Canada) FHT models integrated both mental health professionals and dieticians [32, 41, 42].

Some team-based models (5/15; 33,3%) included a care manager, this role most frequently being filled by a nurse [37,38,39] or a social worker [36]. Care managers facilitate patient engagement and education [28, 36, 41], provide proactive follow-up [28, 36, 37] and coordinate care [28, 36, 37, 41].

Regarding which professional is the entry point for accessing complementary services, the FP was the professional most cited (9/15; 60%), followed by nurses (3/15; 20%). These professionals evaluate patients’ needs and refer them to other professionals, and, in three (3/15;20%) team-based models, they also use a screening tool to detect mental health problems. In the case of Kates’ study [41], dieticians also used screening tools with individuals with diabetes to screen for depression. The trajectory of patients following this initial assessment is infrequently specified in the articles; in only three studies (3/15; 20%) was the existence of a predefined service trajectory or care plan for patients specified.

Regarding the collaboration tools used within the team, the most frequent tools identified include team meetings (5/15, 33,3%), shared electronic medical record or patient registry (8/15; 53,3%), and joint care planning, consultation or management (6/15; 40%). Only two studies explicitly named the patient as an integral part of care planning [33, 34].

The management of the team-based models was described in six studies (6/15; 40%) [33, 36, 40,41,42,43]. They mostly describe how the management roles are shared between professionals or organizations involved, sometimes with a description of these roles, for example: a FP can run the clinic [33]; diverse sites can have one central management team [42]; each practice can be autonomous in decisions [43].

Contexts of emergence of the co-located team-based care models

Consistent with our objectives, we summarized the data regarding contexts to better understand the emerging context of the team-based model and the type of support provided. These data are inconsistently reported across the articles. Nevertheless, we have been able to capture the models’ main goals, the sector’s characteristic in which they have been implemented, if they have been implemented in more than one practice site, and the type of support provided.

The goals of the team-based primary care models studied have been explicitly reported in 7/15 (46,7%) studies. The main goals included: improve access to complementary services, especially mental health services [32, 40,41,42]; improve quality of care, clinical outcomes and patient experience [28, 37, 41]; improve skills of family physician, especially in mental health [34, 41, 42]; use resources more efficiently [41].

The characteristics of the sector in which the model has emerged have been provided by all studies with, however, considerable variability regarding the details. The models were implemented in an urban/suburban area (8/15; 53,3%) [28, 34, 35, 37, 40,41,42,43], in a rural area (3/15; 20%) [29, 33, 39] or in both (1/15; 6,7%) [32]. Some initiatives (3/15; 20%) specifically focused on districts with vulnerable or marginalized populations (e.g., low-income) [35, 36, 39]. Several sectors (4/15; 26,7%) were characterized by poor access to mental health services, resulting in under-treatment of these conditions [30, 33, 34, 41]. In several sectors (3/15; 20%), the family physician’s role was identified as important in providing mental health care [30, 33, 41]. A shortage of specialists was also highlighted in a few sectors (2/15; 13,3%) [33, 34]. Only one model specifically addressed chronic medical conditions; the authors reported that most patients in their area were underserved, and performance needed to be improved [37].

Some models (6/15, 40%) have been developed in only one practice [29, 30, 33, 36, 37, 40]. Others have been deployed locally in several sites; either in one area (8/15; 53,3%) [28, 34, 35, 38, 39, 41,42,43] (e.g., Hamilton, Ontario [41, 42]) or within a single province/state (1/15; 6,7%) [32].

The type of support documented in the article was limited to the type of financial support provided. When reported, the authors provided varying levels of detail regarding funding. The type of funding received varied significantly. It was possible to discriminate the type of physician’s payment and the source of the funding for the complementary services (federal, provincial, private, municipal). The type of physicians’ payment was indicated in 3/15 (20%) articles, all situated in Canada [29, 32, 41]. Physicians within these team-based models were primarily compensated through alternative funding arrangements, with capitation-based funding being the most common approach [32, 41]. Regarding complementary services in the US, Canada and Australia, funding came from federal public funds (3/15; 20%) [28, 39, 40], private foundations (2/15; 13,3%) [36, 43], provincial or state (2/15; 13,3%) [33, 41], or a joint federal and provincial initiative [34]. One model was funded by a local public program (Mental Health and Nutrition Program in Hamilton, Canada) [42]. In another model located in Norway, physicians were paid in three different ways (capitation based, fee-for-service, co-payments by patients). In this model, although mental health professionals provided a free service to patients, these services could not be funded if not provided within these professionals’ own employment structure [30].

Impacts on population, providers and healthcare costs

Study objectives, design, participants, and main results are presented in Table 4 to present the information related to the impacts of the team-based primary care models, and the key factors that influenced these impacts. The results regarding impacts were classified according to their target: patients, providers, and cost-effectiveness. The impact of team-based models on patients have been reported in 14/15 (93,3%) studies, while 7/15 (46,7%) studies reported effects on providers. The main effects on patients include: improved access and reduced stigma, especially for individuals with mental health problems [32, 41, 42]; enhanced chronic disease management [29]; better treatment adherence and follow-up [28, 33, 35]; better relationship with FP [32,33,34]; and improvement in symptoms or functioning [28, 40, 41]. Positive impacts on providers include: upskilling [33, 34, 42]; better job satisfaction [33, 37]; and redistribution of workloads [37].

Some key facilitators of these benefits include: the addition of a care manager [28, 35]; strong leadership and support from the management team [29, 38, 41]; physician’s adherence to the model [29, 41]; stable staffing [33, 38]; individual skills and comfort with new or modified professional roles [29, 41, 42]; and shared vision of the model [41, 43]. The lack of adequate funding is the main barrier reported by the studies [29, 30, 33, 42].

Cost-effectiveness has been documented in 2/15 (13,3%) studies. However, although some organisational and cost savings benefits by ensuring more efficient practices have been reported by Fitzpatrick and colleagues [33] and Scanlon and colleagues’ study [39], they do not show significant changes in cost or use of healthcare resources.

Discussion

Team composition, role optimization and organisation of services

The results indicate that team-based care models have been operationalized in various ways within primary care environments. The models reviewed were predominantly implemented in the United States and Canada, which raises the question regarding the contextual elements that might be associated with the implementation of these kinds of models.

The composition of teams in the reviewed models is diverse, encompassing various professionals in addition to family physicians. With minor exception, the models tend to focus either on the provision of mental health services, on chronic disease management, but rarely on both. Team composition appears to be associated with the nature of the services offered. Evidence suggests that the addition of a broader range of health care providers (e.g., pharmacists, nurse) expands the array of services, and that it improves health outcomes [44]. Our findings suggest that it is also important to consider the type of professionals involved, as the absence of certain professionals in the team may have an impact on the quality of care, the nature of services provided and the optimal use of roles. For example, Vader and colleagues [45] reported that the absence of a physiotherapist within the team limited the quality of services for patients with chronic low back pain. The integration of dieticians or rehabilitation specialists (e.g., physiotherapists, occupational therapists) also appears to be very limited in the models examined. This finding is of concern particularly regarding chronic diseases given the important role that these professionals play in improving patients' day-to-day health and functioning, promoting prevention, and reducing the use of healthcare system resources (e.g., fewer medical visits and hospitalizations) [46,47,48]. Although several models that integrate rehabilitation in primary care exist, most of these are designed for specific populations (e.g., older adults, individuals with disabilities) or in community-based settings [49].

The organisation of the team-based models included in this review emphasizes the role of family physicians as the primary entry point and assessors of patients' needs, as expected in a PMH model. Nevertheless, a few models relied more on nurses (RN or NP depending on the model) to perform these roles, which suggests a greater use of the nurses’ expertise in the team. More generally, some models illustrate the effective integration and versatility of nurses (NPs or RNs), who occupy clinical, coordination and educational roles, as many of the care managers reported were nurses. This finding is consistent with recent studies highlighting both NPs’ essential roles in primary care (e.g., managing patients, improving access to care, dealing with complex health care issues) and the need to improve their integration in primary care teams [50,51,52].

Regarding collaboration, most team-based models used tools (e.g., team meetings, shared electronic records) that facilitated communication and coordination among team members. Support from managers appears to be essential for facilitating collaboration. Our findings are consistent with the findings of Wranik and colleagues’ [44] systematic review, which revealed strong evidence that co-location, shared tools and appropriate leadership are important factors for collaboration. However, the inclusion of patients as integral participants in care planning appeared to be missing from the models reviewed, highlighting the potential for greater patient engagement. This engagement is recognized as an essential aspect of team-based care, especially in PMH [53].

Our review revealed a wide range of model of care approaches underpinning team-based care, which might reflect the flexibility necessary to cater to different healthcare contexts and patient populations. It is important to understand how these approaches influence the organization and delivery of care. As noted, given that most of the studies reviewed were conducted in North America, some prudence is required regarding their applicability within other countries.

Tailoring the models to the specific characteristics and needs of a sector

The models identified primarily target individuals with mental health conditions and chronic diseases. The emphasis on these populations underscores the need for integrated and comprehensive care for individuals with co-morbidities, whether mental health problems or chronic diseases. This point also highlights the necessity to integrate social and health services within the same location, to better respond to these complex healthcare needs [54, 55]. Some initiatives specifically target districts with vulnerable or marginalized populations, for example, low-income communities, highlighting the models' required adaptability to address health disparities. This orientation is consistent with the fifth aim of primary care transformation [5].

No universal socio-demographic or socio-professional characteristics in favor of the development of these team-based models emerged in our review. Rather, what appears to be important is the careful study of the specific characteristics and needs of a sector. Nevertheless, the results permit the identification of elements to consider when implementing a team-based model: the sector (urban, suburban, rural); the population's need for services (e.g., mental health, chronic diseases); the type and ratio of professionals available in the sector, and consequently, the professionals required. The goal is to match the supply, access to, and quality of services in a sector and the population's need for services (type of physical and mental health problems). These elements reinforce Tomoaia-Cotisel and colleagues’ [21] highlighting of important contextual factors at multiple levels (level 1: external environment; level 2: larger organization; level 3: practice), diverse perspectives and data source, and the interactions between contextual factors and both the process and outcome of studies.

Limited integration of population health outcomes, patients’ and providers’ experience and healthcare costs

Our review provides some insights into the outcomes of team-based care models, which encompass a range of benefits for patients and providers. Although some prudence in interpretation is required given that we did not evaluate the methodology of the studies, the models examined appear to generally satisfy the expectations of the overarching framework of a high-performing team-based primary care model at patient and provider levels [3, 6, 56]. On the other hand, the studies revealed few outcomes regarding prevention and patient self-management, even though these are important goals of primary care reform [3].

Only two articles provide results, which are inconclusive, regarding cost-effectiveness [33, 39]. These findings are consistent with those of other studies that have examined various forms of physician and complementary services financing under different models in North America and their cost-effectiveness [17, 57]. Furthermore, our results suggest that there has been little integration of qualitative data regarding patients’ experiences with the cost effectiveness data.

Several studies in our review discussed factors that facilitated or hindered positive outcomes for patients and providers (e.g., inadequate funding, presence of care managers, physician adherence, stable staffing, individual skills, shared vision). These results are consistent with Rawlinson and colleagues’ [20], analysis, in which these barriers and facilitators were classified into four categories: system (e.g., financing, supportive policies and government), organizational (e.g., co-location, effective leadership, shared data system, staffing), inter-individual (e.g., communication, common goals), individual (e.g., resistance to change, intention to collaborate).

Despite inadequate funding being a common barrier in the implementation of the team-based models, limited descriptions of model funding were provided in the reviewed studies. How funds are allocated, the modalities of professional payment, or reimbursement for services remain unclear, as does the distinction between funding for physicians and supplementary services. Funding arrangements appear to be complex as they involve multiple stakeholders at federal, provincial/state, or municipal levels.

Implications for research

Regarding research implications, it is essential to integrate a multi-level analysis to consider elements from the external environment/system (macro level) such as population needs, funding or government policy; larger organization (meso level) such as co-location, leadership or type of provider available; and at the practice/individual (micro level), for example, communication, individual skills and readiness for change or role optimization, to gain a comprehensive understanding of these models. The importance of integrating economic and quantitative evaluations with qualitative aspects is also recognized. Finally, it will be important to identify the most relevant indicators for assessing a model’s performance.

Limitations of the study

The extensive variability in the concepts used, their meanings, and the diversity of implemented models has made the process of selecting and analyzing articles complex. Although the Peek and National Integration Academy Council [58] has attempted to resolve this issue with a lexicon, this tool appears to be seldom used, and was not referred to in our reviewed studies. In our efforts to maintain rigour, several types of models were not included in this review. Models that rely on the integration of coordinated intervention programs were especially numerous. The TEAMcare, IMPACT, or COMPASS programs are examples of this type of program that target the treatment of depressive symptoms and certain chronic conditions [59]. Instead, we have opted for team-based models that rely on the integration of professionals to expand the range of primary care services and improve access without imposing special conditions on access to those services. Furthermore, as our primary focus was on service organization and the context of model implementation, numerous models that could have met the desired model type were excluded. Despite these limitations, the selected articles provided a range of pertinent details. Future research should seek a more comprehensive documentation of these elements and their integration into the model analysis.

Conclusion

Studies rarely provide an overarching view that permits an understanding of the specific contexts, service organization, impact on the population, providers and healthcare costs, and the broader context of implementation. Therefore, it is difficult to identify universal guidelines for the functioning of efficient models. This point highlights the inherent complexity of operationalizing these models. It also underscores the importance of tailoring them to the specific needs and characteristics of a population in a given area, and reflecting on which professionals should be included in the team to truly meet those needs. In this sense, our results permit greater reflection on the deployment of professional role optimization within these co-located team-based models. A collaborative approach with the various stakeholders, including patients, involved in service organization appears to be essential to achieve this outcome.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- FHT:

-

Family health teams

- FMG:

-

Family medecine group

- FP:

-

Family physician

- NP:

-

Nurse practitioner

- PMH:

-

Patient’s medical home

- RN:

-

Registered nurse

References

World Health Organization. Primary care. World Health Organization n.d. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/clinical-services-and-systems/primary-care. Accessed 11 Oct 2023).

World Health Organization. Access to health services “Integrated people-centred health services” PHC-oriented models of care. World Health Organ 2024. https://www.emro.who.int/uhc-health-systems/access-health-services/phc-oriented-models-of-care.html. Accessed 20 May 2024.

Aggarwal M, Hutchison B. Toward a primary care strategy for Canada. Ottawa (CA): Canadian Foundation for Healthcare Improvement; 2012.

Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Taking the pulse: A snapshot of Canadian health care, 2023 2023. https://www.cihi.ca/en/taking-the-pulse-a-snapshot-of-canadian-health-care-2023/88-of-canadians-have-a-regular-health. Accessed 13 May 2024.

Nundy S, Cooper LA, Mate KS. The quintuple aim for health care improvement: a new imperative to advance health equity. J Am Med Assoc. 2022;327:521–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.25181.

Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12:573–6. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1713.

Government of Canada. ARCHIVED- A 10-year plan to strengthen health care 2004. https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-care-system/health-care-system-delivery/federal-provincial-territorial-collaboration/first-ministers-meeting-year-plan-2004/10-year-plan-strengthen-health-care.html. Accessed 11 Oct 2023.

Collins C, Heuson DL, Munger R, Wade T. Evolving models of behavioral health integration in primary care. New York (NY): Milbank Memorial Fund; 2010.

Nelson S, Turnbull J, Bainbridge L, Caulfield T, Hudon G, Kendel D, et al. Optimizing scopes of practice: New models of care for a new health care system. Ottawa (CA): Canadian Academy of Health Sciences; 2014.

Bourgeault IL, Merritt K. Deploying and managing health human resources. Palgrave Int. Handb. Healthc. Policy Gov., London: Palgrave Macmillan UK; 2015, p. 308–24.

Reeves S, Pelone F, Harrison R, Goldman J, Zwarenstein M. Interprofessional collaboration to improve professional practice and healthcare outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:1–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD000072.pub3.

College of Family Physicians of Canada. A new vision for Canada: family practice—the patient’s medical home 2019. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2019.

Sibbald SL, Misra V, daSilva M, Licskai C. A framework to support the progressive implementation of integrated team-based care for the management of COPD: a collective case study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07785-x.

Beck A, Boggs JM, Alem A, Coleman KJ, Rossom RC, Neely C, et al. Large-scale implementation of collaborative care management for depression and diabetes and/or cardiovascular disease. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31:702–11. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2018.05.170102.

Plourde A. Bilan des groupes de médecine de famille après 20 ans d’existence: Un modèle à revoir en profondeur. Montréal: Inst Rech Inf Socioéconomiques; 2022. p. 1–25. https://iris-recherche.qc.ca/apropos-iris/nous-joindre/.

Asarnow JR, Rozenman M, Wiblin J, Zeltzer L. Integrated medical-behavioral care compared with usual primary care for child and adolescent behavorial health: A meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:929–37. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1141.

Carter R, Riverin B, Levesque J-F, Gariepy G, Quesnel-Vallée A. The impact of primary care reform on health system performance in Canada: A systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;16:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1571-7.

McManus LS, Dominguez-Cancino KA, Stanek MK, Leyva-Moral JM, Bravo-Tare CE, Rivera-Lozada O, et al. The patient-centered medical home as an intervention strategy for diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the litterature. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2021;17:317–31. https://doi.org/10.2174/1573399816666201123103835.

Norful AA, Swords K, Marichal M, Hwayoung C, Poghosyan L. Nurse practitioner-physician comanagement of primary care patients: The promise of a new delivery care model to improve quality of care. Health Care Manage Rev. 2019;44:235–45. https://doi.org/10.1097/HMR.0000000000000161.

Rawlinson C, Carron T, Cohidon C, C A, Hong QN, Pluye P, et al. An overview of reviews on interprofessional collaboration in primary care: Barriers and facilitators. Int J Integr Care 2021;21:1–25. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.5589.

Tomoaia-Cotisel A, Scammon DL, Waitzman NJ, Cronholm PF, Halladay JR, Driscoll DL, et al. Context matters: the experience of 14 research teams in systematically reporting contextual factors important for practice change. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11:S115–23. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1549.

Longhini J, Canzan F, Mezzalira E, Saiani L, Ambrosi E. Organisational models in primary health care to manage chronic conditions: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2022;30:565–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13611.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

Reeves, S, Lewin, S, Espin, S, Zwarenstein, M. A conceptual framework for interprofessional teamwork. Interprofessional Teamwork Health Soc. Care. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.; 2010, p. 57–76.

Cancer Care Ontario. 10 tools for implementing new models of care: a guide to change management. Cancer Care Ontario; 2017.

World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF). Operational framework for primary health care: Transforming vision into action. World Health Organization; 2020.

Blackmore MA, Carleton KE, Ricketts SM, Patel UB, Stein D, Mallow A, et al. Comparison of collaborative care and colocation treatment for patients with clinically significant depression symptoms in primary care. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69:1184–7. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201700569.

Lawson B, Dicks D, Macdonald L, Burge F. Using quality indicators to evaluate the effect of implementing an enhanced collaborative care model among a community, primary healthcare practice population. Nurs Leadersh. 2012;25:28–42. https://doi.org/10.12927/cjnl.2013.23057.

Rugkåsa J, Tveit OG, Berteig J, Hussain A, Ruud T. Collaborative care for mental health: a qualitative study of the experiences of patients and health professionals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20:844. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05691-8.

Kates N, Craven M, Bishop J, Clinton T, Kraftcheck D, LeClair K, et al. Shared mental health care in Canada. Can J Psychiatry 1997;42. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674379704200819.

Ashcroft R, Menear M, Greenblatt A, Silveira J, Dahrouge S, Sunderji N, et al. Patient perspectives on quality of care for depression and anxiety in primary health care teams: a qualitative study. Health Expect. 2021;24:1168–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13242.

Fitzpatrick SJ, Perkins D, Handley T, Brown D, Luland T, Corvan E. Coordinating mental and physical health care in rural Australia: an integrated model for primary care settings. Int J Integr Care. 2018;18:1–9. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.3943.

McElheran W, Eaton P, Rupcich C, Basinger M, Johnston D. Shared mental health care: the Calgary model. Fam Syst Health. 2004;22:424–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/1091-7527.22.4.424.

Moore JA, Karch K, Sherina V, Guiffre A, Jee S, Garfunkel LC. Practice procedures in models of primary care collaboration for children with ADHD. Fam Syst Health. 2018;36:73–86. https://doi.org/10.1037/fsh0000314.

Sanchez K, Adorno G. “It’s like being a well-loved child”: Reflections from a collaborative care team. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord 2013;15. https://doi.org/10.4088/PCC.13m01541.

Lyon RK, Slawson JG. An organized approach to chronic disease care. Fam Pract Manag. 2011;18:27–31.

Misra-Hebert AD, Perzynski A, Rothberg MB, Fox J, Mercer MB, Liu X, et al. Implementing team-based primary care models: A mixed-methods comparative case study in a large, integrated health care system. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1928–36. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-018-4611-7.

Scanlon DP, Hollenbeak CS, Beich J, Dyer A-M, Gabbay RA, Milstein A. Financial and clinical impact of team-based treatment for Medicaid enrollees with diabetes in a federally qualified health center. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:2160–5. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc08-0587.

Emerson MR, Huber M, Mathews TL, Kupzyk K, Walsh M, Walker J. Improving integrated mental health care through an advanced practice registered nurse-led program: challenges and successes. Public Health Rep. 2023;138:22S–28S. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549221143094.

Kates N, McPherson-Doe C, George L. Integrating mental health services within primary care settings: the Hamilton family health team. J Ambulatory Care Manage. 2011;34:174–82. https://doi.org/10.1097/JAC.0b013e31820f6435.

Paquette-Warren J, Vingilis E, Greenslade J, Newnam S. What do practitioners think? A qualitative study of a shared care mental health and nutrition primary care program. Int J Integr Care. 2006;6. https://doi.org/10.5334/ijic.164.

Roblin DW, Howard DH, Junling R, Becker ER. An evaluation of the influence of primary care team functioning on the health of Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care Res Rev. 2011;68:177–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077558710374619.

Wranik WD, Price S, Haydt SM, Edwards J, Hatfield K, Weir J, et al. Implications of interprofessional primary care team characteristics for health services and patient health outcomes: A systematic review with narrative synthesis. Health Policy. 2019;123:550–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2019.03.015.

Vader K, Donnelly C, Lane T, Newman G, Tripp DA, Miller J. Delivering team-based primary care for the management of chronic low back pain: An interpretive description qualitative study of healthcare provider perspectives. Can J Pain. 2023;7:2226719. https://doi.org/10.1080/24740527.2023.2226719.

Goodwin R, Hendrick P. Physiotherapy as a first point of contact in general practice: A solution to a growing problem? Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2016;17:489–502. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423616000189.

Howatson A, Clare W, Turner-Benny P. The contribution of dietitians to the primary health care workforce. J Prim Health Care. 2015;7:324–32. https://doi.org/10.1071/HC15324.

Richardson J, Letts L, Chan D, Stratford P, Hand C, Price D, et al. Rehabilitation in a primary care setting for persons with chronic illness – a randomized controlled trial. Prim Health Care Res Dev. 2010;11:382–95. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1463423610000113.

McColl M-A, Shortt S, Godwin M, Smith K, Rowe K, O’Brien P, et al. Models for integrating rehabilitation and primary care: A scoping study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90:1523–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apmr.2009.03.017.

Carryer J, Yarwood J. The nurse practitioner role: Solution or servant in improving primary health care service delivery. Collegian. 2015;22:169–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.colegn.2015.02.004.

Chouinard V, Contandriopoulous D, Perroux M, Larouche C. Supporting nurse practitioners’ practice in primary healthcare settings: A three-level qualitative model. BMC Health Serv Res 2017;17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2363-4.

Perry C, Thurston M, Killey M, Miller J. The nurse practitioner in primary care: alleviating problems of access?. Br J Nurs. 2013;14:255–9. https://doi.org/10.12968/bjon.2005.14.5.17659.

Sharma AE, Grumbach K. Engaging patients in primary care practice transformation: Theory, evidence and practice. Fam Pract. 2017;34:262–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/fampra/cmw128.

Egede L. Disease-focused or integrated treatment: diabetes and depression. Med Clin North Am. 2006;90:627–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.MCNA.2006.04.001.

Oni T, McGrath N, BeLue R, Roderick P, Colagiuri S, May CR, et al. Chronic diseases and multi-morbidity–a conceptual modification to the WHO ICCC model for countries in health transition. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:575. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-575.

Coleman K, Wagner E, Schaefer J, Reid R, LeRoy L. Redefining primary care for the 21st century. White paper. vol. 16. Rockville (MD): AHRQ Publication; 2016.

Jackson GL, Powers BJ, Chatterjee R, Bettger Prvu J, Kemper RA, Hasselblad V, et al. The Patient-Centered Medical Home: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;158:169–78. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-158-3-201302050-00579.

Peek CJ, National Integration Academy Council. Lexicon for behavioral health and primary care integration: concepts and definitions developed by expert consensus. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 2013.

Chauhan M, Niazi SK. Caring for patients with chronic physical and mental health conditions: Lessons from TEAMcare and COMPASS. Focus. 2017;15:279–83. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.focus.20170008.

Doherty WJ, McDaniel SH, Baird MA. Five levels of primary care/behavioral healthcare collaboration. Behav Healthc Tomorrow. 1996;5:25–7.

Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. Milbank Q. 1996;74:511–44.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the Quebec Ministry of Health and Social Services (MSSS). This funding body played no role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, nor in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the final version of this manuscript. YF, AF, CC and MD made substantial contributions to all stages of the research project, including design of the work, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation and revision of this manuscript. NC made a substantial contribution in the design of the work, and in the preparation and revision of this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Frikha, Y., Freeman, A.R., Côté, N. et al. Transformation of primary care settings implementing a co-located team-based care model: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 890 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11291-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11291-7