Abstract

Introduction

Ethiopia strives to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) through Primary Health Care (PHC) by expanding access to services and improving the quality and equitable comprehensive health services at all levels. The Health Extension Program (HEP) is an innovative strategy to deliver primary healthcare services in Ethiopia and is designed to provide basic healthcare to approximately 5000 people through a health post (HP) at the grassroots level. Thus, this review aimed to assess the magnitude of health extension service utilization in Ethiopia.

Methods

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) checklist guideline was used for this review and meta-analysis. The electronic databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, and African Journals Online) and search engines (Google Scholar and Grey literature) were searched to retrieve articles by using keywords. The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) meta-analysis of statistics assessment and review instrument was used to assess the quality of the studies. Heterogeneity was assessed using the I2 statistic. The meta-analysis with a 95% confidence interval using STATA 17 software was computed to present the pooled utilization of health extension services. Publication bias was assessed by visually inspecting the funnel plot and statistical tests using Egger’s and Begg’s tests.

Result

22 studies were included in the systematic review with a total of 28,171 participants, and 8 studies were included in the meta-analysis. The overall pooled magnitude of health extension service utilization was 58.5% (95% CI: 40.53, 76.48%). In the sub-group analysis, the highest pooled proportion of health extension service utilization was 60.42% (28.07, 92.77%) in the mixed study design, and in studies published after 2018, 59.38% (36.42, 82.33%). All studies were found to be within the confidence interval of the pooled proportion of health extension service utilization in leave-out sensitivity analysis.

Conclusions

The utilization of health extension services was found to be low compared to the national recommendation. Therefore, policymakers and health planners should come up with a wide variety of health extension service utilization strategies to achieve universal health coverage through the primary health care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ethiopia strives to achieve Universal Health Coverage (UHC) through Primary Health Care (PHC) by expanding access to services and improving the provision of quality and equitable comprehensive health services at all levels [1, 2]. Primary Health Care (PHC) services are fundamental to improving health and health equity, particularly in the context of low-and middle-income countries [3, 4]. The Health Extension Program (HEP) is an innovative strategy to deliver PHC services in Ethiopia and provides a model for countries struggling to improve health outcomes in a resource-constrained setting [5, 6].

Ethiopia has been implementing a Community Health Program (CHP) called the Health Extension Program (HEP) since 2003, which is planned to improve the health of the community by focusing on preventive, promotional, and selected curative health services with a special focus on maternal and child health [7, 8], and it has made significant contributions in improving access and coverage of key primary healthcare services for the last 15 years [9, 10]. The HEP is intended to give ownership and responsibility for maintaining health to households so that communities are empowered to produce and maintain their health. The program involves women in decision-making processes and promotes community ownership, empowerment, autonomy, and self-reliance [9].

Health Extension Workers (HEWs) are responsible for implementing the 16 HEP packages in five categories. The five categories of HEP were family health services, personal hygiene and environmental sanitation, major communicable and neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), non-communicable diseases (NCDs), and health education and communication. The packages were considered relevant by policymakers to the rural communities and have been delivered through outreach, home visits, and static approaches [2, 11, 12]. The program expanded to urban centers with additional curative services in 2009 [9, 13]. Additionally, in 2016, the government added two new service packages that made up a total of 18 packages with additional standards of commodities and training of HEWs [9]. It is designed to provide basic healthcare to approximately 5000 people through a health post (HP) at the grassroots level. Every HP is staffed by two female health extension workers (HEWs) trained for one year and paid directly by the government [12]. The HEWs spend 75% of their time on home visits to teach and demonstrate HEP packages to family households and the rest of their time in the health post to provide basic health services [14, 15].

The primary purpose of the HEP is to improve access to and utilization of health care particularly for children and mothers [9, 16, 17]. Health service utilization is a result of multiple factors, such as health workers’ behavior and the characteristics of the community (family characteristics, social structure, and perceptions about modern health services) [15, 18]. It is also influenced by enabling factors, such as the availability of health facilities, accessibility to health services, quality of services, and affordability as well as the characteristics of complaints and the intensity of illness [15]. According to Andersen, factors associated with the utilization of health services can be categorized into predisposing, enabling, and needs factors [19].

According to the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) of 2016, the four consecutive EDHS starting in 2000, showed institutional delivery increased from 5 to 26%, antenatal care increased from 27 to 62%, modern contraceptive utilization increased from 6 to 35%, and infant mortality decreased from 97 to 48% [20]. Despite an encouraging trend of accomplishments, Ethiopia still has several poor health outcome indicators related to the health extension program [8]. The second Health Sector Transformation Plan (HSTP II) revealed that the proportion of model households is 18%, open defecation-free is 40%, and households having hand washing facilities with soap and water are 8%, while the targets in 2024/25 are 50%, 60%, 80%, and 58%, respectively [1], which needs an extensive effort in utilization of the health extension services to achieve the target. These poor outcomes are mainly due to low utilization of the HEP and poor access to health services [3, 4, 8].

In Ethiopia, different studies showed that different levels of health extension service utilization ranged from 9.3 to 86% [3, 4, 7, 8, 16, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. However, there is still no consistent evidence about the utilization of health extension services in Ethiopia. Therefore, this study was aimed to assess the utilization of health extension services in Ethiopia through a systematic review and meta-analysis. The findings of the study will contribute to the development of targeted strategies for the provision of health extension services, for designing public health interventions to improve the utilization of health extension services, and for strengthening the community HEP for UHC through primary health care services.

Research question: What is the pooled magnitude of health extension service utilization in Ethiopia?

Methods and materials

Information source and search strategy

This systematic review and meta-analysis was performed by following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [28]. An electronic search strategy was implemented using databases (PubMed, Cochrane Library, and African Journals Online), which were systematically searched to retrieve related articles using keywords. Google Scholar and relevant grey literature were also searched. The literature search technique was conducted by using the keywords (“Service”) OR (“Package”) AND (“Utilization”) OR (“Uptake”) OR (“Usage”) AND (“Health extension worker”) OR (“Community health worker”) AND (“Ethiopia”) OR (“Ethiopian”). All studies conducted up to October 31/2023 were included. We also performed a manual hand search for reference lists of the articles found through the database search and included the articles relevant to our topic of review. The protocol for this systematic review and meta-analysis is registered in the international Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) and obtained a registration number of CRD 42,023,441,568.

Eligibility criteria

For the review, the CoCoPop mnemonic (Condition, Context, and Population) was used to construct a clear and meaningful review question. Condition: health extension service utilization; Context: Ethiopia and Population: all people live in Ethiopia. Studies that reported the magnitude of health extension service utilization in Ethiopia using an observational study design (cross-sectional, case-control, and cohort) on the health extension services, with open or free access to full text and written in English were included.Studies without abstracts and full-texts, reports, and qualitative studies were excluded. Editorials, newspaper articles, and other forms of popular media reports were excluded, as were studies that did not report the magnitude of service utilization provided by health extension workers. Articles were assessed for inclusion using their title and abstract, and then a full review of the articles was done before they were included in the final review.

Data extraction and management

Eligible studies were imported to Endnote v.20, and duplicates were removed. The four independent reviewers (MGT, ETF, DE, and AMD) did the abstract and full-text reviews and extracted data by the Microsoft Excel spreadsheet using a standardized data extraction checklist. Any disagreements and uncertainties during the extraction process were resolved through logical consensus among the four authors, and the final consensus was approved with the participation of the author (TFA). The following data were extracted: author, publication year, study design, place of study, type of package, sample size, and magnitude of service utilization.

Quality assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal checklist was used to assess the quality of studies, which is freely available at https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. We used the following items to evaluate the studies: Inclusion criteria; Description of study subject and setting; Valid and reliable measurement of exposure; Objective and standard criteria used; Identification of confounders; Strategies to handle confounders; Valid and reliable measurement of outcome; and Appropriate statistical analysis. Using the tool as a protocol, the reviewers (MGT, OA, AAT, and EKB) evaluate the quality of the original articles independently. Those studies, with scores of 5 or more in the JBI critical appraisal were considered to have good quality and included in the review. Discrepancies in the quality assessment were resolved through the involvement of the author (TFA) (Table 1).

Statistical analysis

The data were extracted from the studies using Microsoft Excel V.2016, and the extracted data were exported to STATA-17 software for analysis. The articles were summarized by tables and forest plots. The standard error (SE) of health extension service utilization was calculated. The I2 statistical test was computed to check heterogeneity across the studies [29]. Since significant heterogeneity was detected across the studies, a meta-analysis using a random effects model was employed to estimate the pooled magnitude with a 95% CI. The presence of publication bias was checked visually by using a funnel plot and statistically by using Egger’s and Begg’s statistical tests [30]. Subgroup analysis was also done based on the study design and publication year. Sensitivity analysis was also done to evaluate the effect of each study on the pooled magnitude of health extension service utilization by excluding each study.

Result

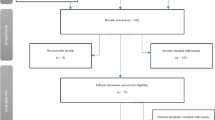

A total of 1690 articles were identified through our initial database search. After duplicate records were removed, 570 records were reviewed by title and abstract. Ninety-one articles were included for full text review. Finally, twenty-two studies were included in the review after applying inclusion and exclusion criteria (Fig. 1). No additional studies were obtained after manual retrieval of the references of the included articles.

Study characteristics

In the systematic review, 22 articles with 28,171 participants were included [3, 4, 7, 8, 16, 17, 21,22,23,24,25,26,27, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. Eight of the studies were from Oromiya [4, 7, 16, 23, 27, 37,38,39], six in the SNNP region [17, 22, 25, 31, 32, 34], four in the Amhara region [8, 21, 33, 36] and four of the articles were from Tigray, Somali, Addis Ababa, and nationwide each region accounts for one study [3, 24, 26, 35]. Fifteen studies were cross-sectional [3, 4, 8, 17, 22, 23, 26, 27, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38], and seven articles were mixed cross-sectional by study design [7, 16, 21, 24, 25, 31, 39]. The maximum sample size was 12,000 households in the Oromiya region [27] and the minimum sample size was 226 in the SNNP region [22]. The year of publication was ranged from 2013 to 2023, five studies were conducted in 2020, 14 studies were done between 2013 and 2019, and three studies were between 2022 and 2023. Five of the included studies [3, 7, 8, 16, 25] were assessed the utilization of urban health extension packages (Table 2). Eight studies reported the proportion of health extension service utilization without specification of the packages. From the included 22 studies, 14 studies reported different outcomes related to the utilization of health extension services, which weren’t reported in other studies. Out of 14 articles with different reported service outcomes, eleven studies [16, 17, 22, 23, 27, 31,32,33,34,35, 37] focused on the utilization of the maternal and child health service package of the health extension program. One of the studies in Somali region emphasized on tuberculosis screening service provided by HEWs [24], the others were aimed on the sexual reproductive health [26] and basic health services provided by HEWs [36].

Magnitude of health extension services utilization

The prevalence of health extension services utilization in individual studies ranged from 9.3 to 92.4% [27, 39]. The eight included studies were from the Oromiya region, which were conducted at different periods of time, showed that the magnitude of health extension service utilization was 39%, 73.1%, 9.3%, 14.2%, 72.8%, 51.7%, 92.4% and 41.8% [4, 7, 16, 23, 27, 37,38,39]. The six included studies were from the SNNP region, which were conducted at different periods of time, showed that the magnitude of health extension service utilization was 19%, 69.82%, 61.7%, 12.4%, 32.8% and 46.47% [17, 22, 25, 31, 32, 34]. The four included studies were from Amhara region and were conducted at different periods of time, showed that the magnitude of health extension service utilization was 59.5%, 78.5%, 15.13% and 14.8% [8, 21, 33, 36]. Four different studies were from Addis Ababa, Tigray, Somali and nationwide showed that the magnitude to be 86%, 24.1%, 20.3% and 19.18% respectively [3, 24, 26, 35].

From the 22 included studies in the systematic review, 14 studies reported outcomes that are not reported in any other included studies, only eight studies [3, 4, 7, 8, 21, 25, 38, 39] which reported similar outcome the proportion of health extension service utilization were included in the quantitative synthesis (meta-analysis).

The estimated overall magnitude of health extension services utilization is presented in a forest plot (Fig. 2). The overall pooled magnitude of health extension service utilization was 58.5% (95% CI: 40.53, 76.48%). Based on the tau square (between study variance), tau2 = 669.40 & I2 = 99.61% with p value < 0.01 which indicates there is statistically significant heterogeneity among studies.

Subgroup analysis

Subgroup analysis was done based on the study design and publication year. Based on this, the magnitude of health extension service utilization was found to be 56.60% and 60.42% in cross-sectional and mixed study designs, respectively. On the other hand, the magnitude of health extension service utilization was 55.87% and 59.38% in studies conducted before and after 2018, respectively (Table 3).

Publication bias

The publication bias was assessed by using a funnel plot (subjectively), and Egger’s and Begg’s tests (objectively). In this study, a funnel plot showed a symmetrical distribution (Fig. 3). Eggers and Begg’s tests also showed no evidence of publication bias at the 0.05 significance level, with a P-value of 0.8155 and 1.00, respectively.

Sensitivity analysis

The meta-leave-out sensitivity analysis was done to estimate the effect of each study on the pooled magnitude of health extension service utilization by eliminating each study step by step. The result showed that no studies were found to be outside the confidence interval of the pooled proportion of health extension service utilization. Therefore, it showed that all studies had nearly equal influence on the overall pooled proportion of health extension service utilization by excluding the leave-out study from meta-analysis (Fig. 4).

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis was aimed at estimating the pooled magnitude of health extension service utilization in Ethiopia. The emphasis of this review was to assess the pooled magnitude of health extension service utilization for a better understanding of service delivery and provision at the grassroots level.

The community health extension services are crucial for marginalized groups who face significant barriers to healthcare, particularly in low- and middle-income countries [40,41,42,43,44], and Community Health Workers (CHWs) are one of the cornerstones of comprehensive PHC by providing basic health services and contributing to achieving the key principles of community health and PHC: equity, responding to local health needs, community involvement, and inter-sectorial collaboration [45, 46].

This review revealed that, from the included eight studies, the pooled magnitude of health extension service utilization was found to be 58.5% (95% CI: 40.53, 76.48%). The result of this review was in agreement with a finding from the Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) of antenatal care (ANC) utilization, which was 62.8% [47], and postnatal care (PNC) utilization of 47% [48]. It was also consistent with findings documented in a study considering child health service delivery by female community health volunteers in Nepal, with a reported child health service provision of 62.6% [49]. Besides, the finding of this review was also comparable with the study conducted in India; the magnitude of community healthcare workers visit was 46.1% [50], and the national utilization of ANC by community health workers in India was 48.9% [51]. Furthermore, it was consistent with studies conducted in western Kenya on the contribution of community health workers for maternal health services (delivery 48% and ANC 66%) [52].

However, the finding of this review was higher than the 2016 EDHS report on institutional delivery service, 26% [20]. The possible justification might be due to the difference in the outcome variable where this review focused on HEP of multiple packages rather than a single service as the only institutional delivery service. It was also higher than a study conducted in community health workers contribution on glycemic control in lower income countries, 21% [53]. The possible explanation for the variation might be due to the methodological differences in which our review included cross-sectional studies rather than a randomized control trial on a glycemic control contribution review of lower income countries. Additionally, the finding of this review was also higher than a study done in Uganda, 27.3% [54]. The possible explanation for this variation might be attributed to the sample size of the study in Uganda, and it was focused on the CHWs contribution from the overall utilization of Integrated Community Case Management (ICCM) services that might be provided by other stakeholders in the study area. Furthermore, this study finding was also higher than a review considered health service utilization in Brazil, 71% [55]. The reason for the variation might be due to the definition of the outcome variable, in which the previous study focused on the overall utilization of health services by all healthcare providers, whereas this review emphasized the utilization of health extension services. The health systems, policies, and government structure might also be the reason for the difference.

The result of this review was lower than a study conducted on the long acting reversible contraception contribution by CHWs in Rwanda, 79% [56] and modern health service utilization in Southern Ethiopia, 77.2% [57]. The possible reason for the variation might be attributed to our study was the pooled result from different studies.

The subgroup analysis of this systematic review and meta-analysis showed that there was no significant difference in health extension service utilization by study design and publication year.

Policy implications

The result we presented showed that interventions should be taken to increase the utilization of health extension services in Ethiopia. The policymakers might use the finding of this study as an input for developing different health extension service utilization improvement strategies.

Limitation

The number of studies included in the meta-analysis was small, which may affect the result of the pooled magnitude of health extension service utilization by affecting the precision. We can’t include all the studies in the meta-analysis due to reporting of different outcomes in relation to the HEP.

Conclusion

This systematic review and meta-analysis reported that health extension service utilization was low compared to the national recommendation. Therefore, the government and policymakers should come up with different mechanisms, including a wide variety of health extension service utilization strategies, so as to achieve universal health coverage through primary health care. Further meta-analysis should also be recommended to identify the associated factors.

Data availability

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplemental information.

Abbreviations

- CHWs:

-

Community Health Workers

- HEWs:

-

Health Extension Workers

- HEP:

-

Health Extension Program

- HES:

-

Health extension service

- UHC:

-

Universal Health Coverage

References

Ministry of Health. Health Sector Transformation Plan II. Addis Ababa; 2021.

Ministry of Health. Health sector transformation plan I. FMOH: Addis Ababa; 2015.

Girmay AM, et al. Urban health extension service utilization and associated factors in the community of Gullele sub-city administration, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Int J Community Med Public Health. 2019;6(3):976–85.

Kelbessa Z, Baraki N, Egata G. Level of health extension service utilization and associated factors among community in Abuna Gindeberet District, West Shoa Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–9.

Assefa Y, et al. Community health extension program of Ethiopia, 2003–2018: successes and challenges toward universal coverage for primary healthcare services. Globalization Health. 2019;15:1–11.

Workie NW, Ramana GN. The Health Extension Program in Ethiopia, in UNICO studies Series 10. World Bank Washington DC; 2013.

Gebreegziabher EA, et al. Urban health extension services utilization in Bishoftu town, Oromia regional state, Central Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–10.

Molla S, Tsehay CT, Gebremedhin T. Urban health extension program and health services utilization in Northwest Ethiopia: a community-based study. Risk Manage Healthc Policy, 2020: p. 2095–102.

Federal Ministry of Health, Second Generation Health Extension Program. 2015: Addis Ababa

Teklu A, et al. National assessment of the Ethiopian health extension program. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: MERQ Consultancy PLC; 2019.

FMOH, Health extension program, evaluation and optimization document. 2018

Federal Ministry of Health, Health service extension programme: implementation guideline. 2005

Gobezie WA et al. Relevance of the Health Extension Program to the current health needs and evolving demands of Rural Ethiopia: a mixed-method analysis. Ethiop J Health Sci, 2023. 33(2).

Tadesse D, et al. Unmet need for family planning among rural married women in Ethiopia: what is the role of the health extension program in reducing unmet need? Reproductive Health. 2022;19(1):1–10.

Yitayal M et al. The community-based Health extension program significantly improved contraceptive utilization in West Gojjam Zone, Ethiopia. J Multidisciplinary Healthc, 2014: p. 201–8.

Berri KM, et al. Maternal health service utilization from urban health extension professionals and associated factors among women who gave birth in the last one year in Ambo town, Oromia regional state, Ethiopia, 2018. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–10.

Negussie A, Girma G. Is the role of Health Extension workers in the delivery of maternal and child health care services a significant attribute? The case of Dale district, southern Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17:1–8.

Tafesse N, Gesessew A, Kidane E. Urban health extension program model housing and household visits improved the utilization of health services in Urban Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–11.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav, 1995: p. 1–10.

CSA I. Central Statistical Agency. Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa: CSA and ICF; 2016.

Aynalem BY, Melesse MF. Health extension service utilization and associated factors in East Gojjam Zone, Northwest Ethiopia: a community-based cross-sectional study. PLoS ONE. 2021;16(8):e0256418.

Bayou NB, Gacho YHM. Utilization of clean and safe delivery service package of health services extension program and associated factors in rural kebeles of Kafa Zone, Southwest Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2013;23(2):79–89.

Gela BD, et al. Antenatal care utilization and associated factors from rural health extension workers in Abuna Gindeberet district, West Shewa, Oromiya region, Ethiopia. Am J Health Res. 2014;2(4):113–7.

Getnet F, et al. Low contribution of health extension workers in identification of persons with presumptive pulmonary tuberculosis in Ethiopian Somali Region pastoralists. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–9.

Jikamo B, Woelamo T, Samuel M. Utilization of urban health extension Program services and associated factors among hosanna dwellers, Hadiya zone, southern Ethiopia: a community based cross-sectional study 2019.

Jisso M, et al. Sexual and reproductive health service utilization of young girls in rural Ethiopia: what are the roles of health extension workers? Community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ open. 2022;12(9):e056639.

Shaw B, et al. Determinants of utilization of health extension workers in the context of scale-up of integrated community case management of childhood illnesses in Ethiopia. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2015;93(3):636.

Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med; 2009. Altman DG.

Higgins J, Green S. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: cochrane book series. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions: cochrane book series. 2008. 2008, John Wiley & Sons Location: Hoboken, New Jersy, USA.

Sterne JA. And M.J.J.o.c.e. Egger, funnel plots for detecting bias in meta-analysis: guidelines on choice of axis. 2001. 54(10): p. 1046–55.

Hadaro DD, Temesgen Tantu MG, Zewudu D. Health Extension Postnatal Care Services Utilization and Associated factors among mothers in Kindo Didaye District, Southern Ethiopia: a community-based mixed-method study J. Women Health Care Issues, 2022. 5(3).

Gebretsadik A et al. Home-based neonatal care by Health Extension Worker in rural Sidama Zone southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study Pediatric health, medicine and therapeutics, 2018: pp. 147–155.

Asmamaw DB, et al. Early postnatal home visit Coverage by Health Extension Workers and Associated factors among Postpartum women in Gidan District, Northeast Ethiopia. Int J Public Health. 2023;68:1605203.

Gebretsadik A, et al. Health extension workers involvement in the utilization of focused antenatal care service in rural sidama zone, Southern Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Health Serv Res Managerial Epidemiol. 2019;6:2333392819835138.

Tesfau YB, et al. Postnatal home visits by health extension workers in rural areas of Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study design. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Yitayal M, et al. Health extension program factors, frequency of household visits and being model households, improved utilization of basic health services in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):1–9.

Birhanu Z, et al. Mothers’ experiences and satisfactions with health extension program in Jimma Zone, Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13(1):1–10.

Zeleke AT, Molla DT, Kassa NA. Factors associated with Health Extension Service utilization in Dera District, Oromia, Ethiopia: a multi level analysis. Am J Theoretical Appl Stat. 2019;8(3):85–93.

Sinki MU et al. Level of Health Extension Service utilization and Associated factors among community of Merti Woreda Arsi Zone, Oromia Regional State, Ethiopia.

Ahmed S, et al. Community health workers and health equity in low-and middle-income countries: systematic review and recommendations for policy and practice. Int J Equity Health. 2022;21(1):49.

Kok MC, et al. Optimising the benefits of community health workers’ unique position between communities and the health sector: a comparative analysis of factors shaping relationships in four countries. Glob Public Health. 2017;12(11):1404–32.

Ludwick T, et al. The distinctive roles of urban community health workers in low-and middle-income countries: a scoping review of the literature. Health Policy Plann. 2020;35(8):1039–52.

Pallas SW, et al. Community health workers in low-and middle-income countries: what do we know about scaling up and sustainability? Am J Public Health. 2013;103(7):e74–82.

Watkins JA, Griffiths F, Goudge J. Community health workers’ efforts to build health system trust in marginalised communities: a qualitative study from South Africa. BMJ open. 2021;11(5):e044065.

Javanparast S, et al. Community health worker programs to improve healthcare access and equity: are they only relevant to low-and middle-income countries? Int J Health Policy Manage. 2018;7(10):943.

Tilahun D, et al. Training needs and perspectives of community health workers in relation to integrating child mental health care into primary health care in a rural setting in sub-saharan Africa: a mixed methods study. Int J Mental Health Syst. 2017;11:1–11.

Tsegaye B, Ayalew M. Prevalence and factors associated with antenatal care utilization in Ethiopia: an evidence from demographic health survey 2016. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Mekonnen T, et al. Postnatal care service utilisation in Ethiopia: reflecting on 20 years of demographic and health survey data. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(1):193.

Bhattarai HK, et al. Factors associated with child health service delivery by female community health volunteers in Nepal: findings from a national survey. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):1–8.

Seth A, et al. Differential effects of community health worker visits across social and economic groups in Uttar Pradesh, India: a link between social inequities and health disparities. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16:1–9.

Nadella P, Subramanian S, Roman-Urrestarazu A. The impact of community health workers on antenatal and infant health in India: a cross-sectional study. SSM-Population Health. 2021;15:100872.

Akinyi C, Nzanzu J, Kaseje D. Effectiveness of community health workers in promotion of maternal health services in Butere district, rural western Kenya. Univers J Med Sci. 2015;3(1):11–8.

Palmas W, et al. Community health worker interventions to improve glycemic control in people with diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:1004–12.

Muhumuza G, et al. Acceptability and utilization of community health workers after the adoption of the integrated community case management policy in Kabarole District in Uganda. Volume 2. Health systems and policy research; 2015. 1.

Araújo MEdA, et al. Prevalence of health services utilization in Brazil: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Volume 26. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde; 2017. pp. 589–604.

Mazzei A, et al. Community health worker promotions increase uptake of long-acting reversible contraception in Rwanda. Reproductive Health. 2019;16:1–11.

Workie SB et al. Modern health service utilization and associated factors among adults in Southern Ethiopia Journal of Environmental and Public Health, 2021. 2021.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.G.T., E.T.F., A.A.T., E.K.B. and T.F.A. developed the protocol and were involved in the design, selection of study, data extraction, and statistical analysis. M.G.T., D.E., and O.A.T. were involved in data extraction and quality assessment. M.G.T. and A.M.D. were developing the initial drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final draft of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tiruneh, M.G., Fenta, E.T., Endeshaw, D. et al. Health extension service utilization in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 24, 537 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11038-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-024-11038-4