Abstract

Background

Even though the global maternal mortality has shown an impressive decline over the last three decades, the problem is still pressing in low-income countries. To bring this to an end, women in a continuum of maternity care should be retained. This study aimed to assess the status of Ethiopian women’s retention in the continuum of maternity care with their possible predictors.

Methods

We used data from the 2019 Ethiopian Mini-Demographic and Health Survey. The outcome variable in this study was retention in the continuum of maternity care, which consists of at least four ANC contacts, delivery in a health facility, and postnatal check within 48 h of delivery. We analyzed the data using STATA version 14 and a binary logistic regression model was used. In the multiple logistic regression model, variables with a p-value ≤ 0.05 were considered as significantly associated with the outcome variable. A weighted analysis was also done.

Results

Of the 3917 women included in this study, only 20.8% of women completed all of the recommended services. Besides, the use of maternal health services favors women living in the biggest city administrations, followed by women living in agrarian regions; however, those living in the pastoralist area were disadvantaged. Having four or more ANC was explained by the maternal secondary level of education [AOR: 2.54; 95% CI: 1.42, 4.54], wealth status [AOR: 2.59; 95% CI: 1.45, 4.62], early initiation of ANC [AOR: 3.29; 95% CI: 2.55, 4.24], and being in a union [AOR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.16,3.29]. After having four ANC, factor-affecting delivery in a health facility was wealth status [AOR: 8.64; 95% CI: 4.07, 18.36]. The overall completion of care was associated with women’s higher level of education [AOR: 2.12; 95% CI: 1.08, 4.25], richest wealth status [AOR: 5.16; 95% CI: 2.65, 10.07], timeliness of the first ANC visit [AOR: 2.17; 95% CI: 1.66, 2.85], and third birth order [AOR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.35, 0.97].

Conclusions

Despite the efforts by the Ethiopian government and other stakeholders, the overall completion of care was quite low. There is also a clear inequality because of women's background characteristics and regional variation. Strategies aiming to empower women through improved educational experience and economic standing have to be implemented in collaboration with other relevant sectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Even though the global Maternal Mortality Ratio (MMR) and neonatal mortality over the last two and three decades have shown an annual 2.9% and a 2.5% decline respectively [1, 2], the problem is still pressing in Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC). MMR is disproportionately higher in low-income regions: for instance, from the total pregnancy and childbirth-related maternal mortality, 7 out of 10 were from Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) countries [3, 4]. As a result, the MMR in low-income countries is about 479 per 100,000 live births, whereas it is 41 per 100,000 live births in high-income countries [5]. In Ethiopia, about 112,000 newborn babies and 14,000 mothers die each year due to preventable causes [6, 7].

To bring this to an end, in 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) launched a strategy to End Preventable Maternal Mortality (EPMM) through the maternal health service continuum across the stages of pregnancy, delivery, and postpartum periods [8]. By then, to meet the WHO's global target of reducing MMR to less than 70 per 100,000 live births on one side, and to lower neonatal mortality to less than 12 per 1000 Live births by 2030 on the other hand [9]. In Ethiopia, as part of the strategies, the government identified maternal, newborn, and child health as a priority agenda aiming to reduce the MMR from 412 to 42 per 100,000 live births by the end of 2035. In addition, with a thorough investment in maternal health services, neonatal mortality was planned to be reduced to 21 per 1000 live births in 2024/25 [10,11,12].

The maternity continuum of care is integrated care; to provide essential health care packages during pregnancy, childbirth, and postnatal periods. It is a focal point of health systems in many countries to minimize preventable maternal loss and complications in most instances and to make pregnancy and childbirth a positive experience in other cases [13]. The provision of the three integrated care including; antenatal care (ANC), delivery in a health facility, and postnatal care (PNC), as a continuum has gained global attention as one of the strategies to improve maternal and neonatal health outcomes [14]. As the evidence shows, complete coverage of the maternity continuum of care could avert an estimated 71% maternal mortality ratio (MMR) [15], and 56% of neonatal death worldwide [16].

As evidence suggests failing to obtain any of the care along the continuum is associated with discontinuity between maternal and child health programs which results in unfavorable maternal and neonatal outcomes [14, 17, 18]. Although studies show the completion of maternity services in Ethiopia, the findings are either limited to some geographic area/region, [15, 19], or the results present inconsistent figures ranging from 14 to 47% or focus on some services [15, 16, 20, 21]. In this paper, we set out to examine the degree of retaining clients within the continuum of maternity care in Ethiopia using recent nationally representative data. We also report on predictors of retention along the continuum of care and at completion.

Method and materials

Study setting and period

This study was conducted in Ethiopia, Africa’s oldest independent state situated in East Africa. Administratively, it is organized into seven agrarians (agriculture as the way of living) regions, two pastoralists (livestock raising as the way of living), two regions with both agrarian and pastoralist areas, and two chartered cities [22]. The population of Ethiopia is around 120 million, where nearly 25 million are shared by women of reproductive age [23]. The health system is federally decentralized along the eleven regions and two city administrations. Access to health care is an exigent challenge in Ethiopia, where around 5215 healthcare facilities managed by the public sector are there for the total population [24]. In addition, the health professional (Medical Doctors, Midwives, and Nurses) to population ratio was below the minimum requirement for SSA, 1.81 per one thousand population, in the year 2019 [25]. The study was conducted from March 21 to June 28, 2019.

Population and sampling

In the study; we used data from the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) database [26]. The sampling frame was a complete list of 149,093 enumeration areas (EAs) created for the 2019 Ethiopia Population and Housing Census (PHC). An EA is a geographic area covering an average of 131 households. The stratification made urban and rural areas for each region and administrative city, yielding a sum of 21 sampling strata.

Samples of EAs were selected independently in each stratum in two stages. In the first stage, 305 EAs (93 in urban areas and 212 in rural areas) were selected with probability proportional to EA size and with independent selection in each sampling stratum. A household listing operation was carried out in all selected EAs from January through April 2019. The resulting lists of households served as a sampling frame for the selection of households in the second stage [27].

Some of the selected EAs for the 2019 EMDHS were large, with more than 300 households. To minimize the task of household listing, each large EA selected for the 2019 EMDHS was segmented. Only one segment was selected for the survey, with probability proportional to the segment size. Household listing is conducted only in the selected segment, that is, a 2019 EMDHS cluster is either an EA or a segment of an EA. In the second stage of selection, a fixed number of 30 households per cluster were selected with an equal probability of systematic selection from the newly created household listing [27]. Women of the reproductive age group, who gave birth within 5 years preceding the survey, were the source population for this study.

All women of reproductive age group, either permanent residents of the selected households or visitors, were eligible for interview. In households with more than one eligible woman, one woman per household was randomly selected.

Data collection

The survey team used DHS Program's standard tools that were adapted to reflect the population and health issues relevant to Ethiopia. Maternal health service-related information was collected using the women's questionnaire among the five questionnaires in the DHS program surveys. The questionnaire includes items related to respondents' background characteristics, reproduction, contraception, pregnancy and postnatal care, child nutrition, childhood immunizations, and health facility information. The Survey was implemented by the Ethiopian Public Health Institute (EPHI), in partnership with the Central Statistical Agency (CSA) and the Ethiopian Ministry of Health (MOH). Seventeen trainees who had some experience on previous Ethiopian DHS surveys obtained training from February 11–20, 2019, and proceeded to data collection after field practice and a debriefing session. The data was collected electronically using tablet computers [28].

Study variables and measurement

Outcome variable

The outcome variable in this study was the continuum of maternal health care. The continuum of care involves attending at least four ANC contacts, delivery in a health facility, and post-natal check within 48 h of delivery. The completion of maternal health service was declared if a woman obtained four or more ANC contacts, delivered in a health facility, and had a postnatal check within 48 h from delivery [29] [Fig. 1].

Four or more ANC means a woman who received four or above ANC contacts during her pregnancy according to the recommendation of the Ethiopian Ministry of Health during the study period [30]. The variable is a binary variable with two categories. We defined institutional delivery (ID) as a mother who gave birth in a health facility (private or public) with the necessary assistance. This variable was also a binary categorical variable. Similarly, PNC was also a binary variable categorized as 1, if the mother got check-ups within 48 h from delivery, and 0, otherwise.

Independent variables

To identify the predictors of the continuum of maternal health services in this analysis several independent variables were assesed. The independent variables include the age of the mother, the mother's level of education, birth order, place of residence (urban/rural), wealth quintile, the timing of the first ANC, mother's marital status, sex of the head of the household, history of child death, and mode of delivery.

Bias

To minimize the possible bias, missing response categories like “don’t know”, “Missing”, inconsistent” were excluded when calculating basic statistics during data analysis. In addition, all analyses were adjusted for cluster and sampling weights for disproportionate stratification of recruited participants.

Data analysis

We analyzed the data using STATA version 14. The analysis involved both descriptive and inferential statistics. Mostly, frequency and proportions were used to describe relevant characteristics of the study participants. We used a binary logistic regression model in two steps to identify predictors of completion in the continuum of maternity care. Primarily we did simple binary logistic regression for each of the independent variables. Variables with p-value ≤ 0.25 were candidates for inclusion in the multiple logistic regression models. Finally, a p-value ≤ 0.05 was used to declare the statistical significance of associations. We did a weighted analysis to account for disproportionate stratification for different sampling units, and to be able to generalize the findings to the national reference population.

Results

Description of the study participants

Around 3,979 women met the inclusion criteria, and 3,917 of them were included in the final analysis. Of the total women, the highest proportion (30.4%) were 25–29 years old, and most of them were married (93.8%). Coming to the place of residence, nearly three-fourths (73.9%) of them were rural dwellers. The highest proportion (51.3%), (21.0%) of them had no education at all and lies at the poorest wealth indices respectively. on the other side; most of them (86.6%), (77.9%) were male-headed households [HHs], and do not have a child's death history respectively [Table 1].

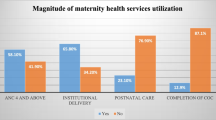

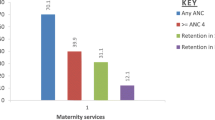

The status of completion of maternal health services

From the total 3,917 women included in the analysis, around three-fourths 2,913 (74.38%) of the women had their first ANC contact. From those who had the first ANC, more than half (57.6%) made it to the fourth or more ANC contacts; about 70% of women who had four or more ANC contacts gave birth in a health facility; furthermore, more than 70% of mothers who delivered in a health facility had PNC within 48 h of their delivery. Overall, 20.8% of pregnant women included in this study completed the continuum of care for their latest child [Fig. 2].

The status of completion of maternal health services across regions

Completion of the maternal health service has shown to be higher in the capital city of Ethiopia, Addis Ababa, followed by the Tigray region and Dire Dawa city administration. The proportion of women who had first ANC contact is higher in Addis Ababa (96.8%), followed by Tigray and Gambella regions (94.7%), (86.3%) respectively. Sustaining the contact up to ANC 4 is similarly higher in Addis Ababa (85.4%), followed by Dirre-Dawa city administration, and Tigray regions. Women who had both at least 4 ANC contacts, and health facility delivery are likewise higher in Addis Ababa (97.7%), followed by Harrar, and Tigray regions. The status of completion for all services (ANC1, ANC 4, institutional delivery, and PNC) is higher in Addis Ababa (64.1%), followed by Tigray (45.2%), and Dire Dawa city administration (33.5%) [Table 2].

Components of maternal health services

This study indicated that the use of maternal health services favors women living in the biggest city administrations followed by women living in mostly agrarian regions. Making 82.1% of the whole pregnant women, women living in city administrations had at least four ANC contacts. Early initiation of first ANC contact is correspondingly higher for women in the two city administrations (65.3%); followed by those living in pastoralist regions (46.1%). Almost all (94.8%) of women residing in the city delivered at the health facility, while this goes down by half (47%), and one-third (30.5%) for agrarian, and pastoralist women respectively. For around three-fourths (76.7%) of women living in the city post-natal check-up was made, whereas, similar was done for around one-third (35%), and only thirteen (25.6%) of agrarian, and pastoralist women respectively. Caesarian delivery service on the other hand has been applied for one-quarter of women living in the city administrations [Table 3].

The relation between the time of initiation of first ANC contact and the continuum of care.

As found in this study, for women who started their first ANC in the early 8 weeks, the chance of completion of the continuum was highest, and the chance of completion starts to go down as the weeks of first contact increased [Fig. 3].

Factors associated with the status of the continuum of maternity care

Having four or more ANC was explained by mothers’ level of education. Women who attended secondary education were 2.5 folds higher (AOR: 2.54; 95% CI: 1.42–4.54) than uneducated women. Women's wealth status was the other factor for complete ANC attendance; richer women were 60% (AOR: 1.6; 95% CI: 1.11–2.32), and the richest women had two and a half folds (AOR: 2.59; 95% CI: 1.45–4.62) of a better chance of having complete ANC than the poorest women. Early initiation of the first ANC is the other factor having potential. As compared to women who were late to start their ANC, those who started earlier have three times (AOR: 3.29; 95% CI: 2.55–4.24) a better chance to attend four or more ANC. Finally, those who were in the union were two times (AOR: 1.95; 95% CI: 1.16–3.29) more likely to have four or more ANC attendance than women who were not in a union.

In our analysis, we found that after having four complete ANC the main factor affecting delivery in a health facility was wealth status. Institutional delivery among those who had at least four ANC was associated with the wealth status of the women. Especially the richest women were eight times more likely to deliver in a health facility (AOR: 8.64; 95% CI: 4.07–18.36) after having four complete ANC. The only factor we found affecting PNC after having four ANC and institutional delivery services is delivery by the caesarian section.

The overall completion of care was associated with women’s level of education. Those with secondary (AOR: 2.74; 95% CI: 1.24–6.07), and higher education, (AOR: 2.12; 95% CI: 1.10–4.25) were twice more likely to complete the course of care than uneducated women. The wealth status of the women was the other one. Compared to the poorest women, all other categories of wealth have a positive effect on completing a full continuum of care with an increasing pattern. For instance, the richest women had a five times more likelihood of completing all maternal health services compared to the poorest (AOR: 5.16; 95% CI: 2.65–10.07). Early initiation of the first ANC was found to have a positive effect on completing the maternal continuum of care (AOR: 2.17; 95% CI: 1.66–2.85). The birth order of the child is another factor affecting the continuum of care, whereby as compared to a woman with a child who was born first the chance of completion of care is about 42% less likely (AOR: 0.58; 95% CI: 0.35–0.97) for those who were born in the third order [Table 4].

Discussion

Reliant on the plausible benefit of completion of the recommended service during and after pregnancy, the maternity continuum of care got attention all over the world as a critical health intervention intending to improve both maternal and child health outcomes [31]. Respectively, the practice obtained recognition in Ethiopia a couple of decades back, and as a result maternal, and child mortality has reduced by half from the devastating Figure [32]. Despite the dramatic achievements from the lowest base, maternal death and morbidities are still stagnant which is partly attributable to the dropout of women from the recommended services during pregnancy, delivery, and post-partum periods. This study assessed women's level of accomplishment in care and the possible predictors of success.

The study found that of all women who gave birth within five years preceding the survey, only around one-fifth of them went through all the services during pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum periods. This finding is in line with a report from the primary health care project in northern Ethiopia (21.6%) [21] and with a national study (21.5%) in the year 2019 [29]. It is revealed as there are improvements regarding completion of service as compared to previous studies like EDHS in 2016 [33], other local studies [34, 35], and SSA and South Asia [4, 36]. The improvement may be attributed to the Ethiopian government's and collaborators’ massive effort for implementing initiatives throughout the nation [37, 38]. Despite the progress made the figure is quite low compared to the findings in other developing countries like Pakistan (27%) [39], Zambia (38%) [18], Ghana (66%) [40], Cambodia (50%) implicating the need for an immense effort.

On the other hand, completion of the care had greater disparities across the regions, it was higher in the 2 city administrations; Addis Ababa (64.1%), Dire Dawa (33.5%), and Tigray region (45.2%), but it was unacceptably low in Somalia region (2.9%). This regional variation is similar to the synthesized information from previous studies in Ethiopia and other developing countries [33, 41,42,43]. The higher percentage of women who completed the continuum of care in the city is possibly due to the relatively better access to care so there is no way to discontinue the care due to transportation costs or, long walking hours to reach the facility [44]. In addition, formally employed women are abundant in urban areas, and most likely to be educated, which gives a woman better insight and understanding of the worthiness to follow the course. On the other hand, another national study indicated that despite the tremendous progress in health, it remains uneven between regions and cities [45].

Related to the above scenario attending the care at each spot has been shown to favor urban women more than those agrarian and pastoralists; obtaining the three services was like a fantasy for the pastoralist women. This finding is supported by earlier studies in Ethiopia [15, 46, 47]. In the pastoralist community, where cattle breeding is the main economic activity to support living, most people travel a lot to find grazing land and water for their cattle making accessing the health centers more challenging and [48] creating a bottleneck to care-seeking, and facilities available were poorly equipped. A study from one of the pastoralist areas in Ethiopia concluded that more than 85% of MM in the region were due to direct obstetric causes while according to the WHO estimate among all MMs around the globe, nearly 70% were attributable to direct obstetric causes [49]. This implies a higher burden of MM associated with the childbearing process in the pastoralist regions.

The overall completion of care was associated with women’s level of education. Those with secondary, and higher education were two times more likely to complete the course of care than those uneducated. This finding is commensurate with various earlier reports [50,51,52,53]. Education often plays a preventive role which gives women a positive influence to adhere to care either through enhancing their socio-economic status [54] or through boosting their knowledge and confidence.

Wealth status was a major characteristic, which had a strong effect on completing the continuum of care. Compared to the poorest, those in the other categories of wealth were more likely to go through all services, and the probability of service use increases as the wealth of the woman increases. Furthermore, wealth status is the only variable that had an effect at each step along the way to the continuum of maternity care. It affects ANC use, it also affects institutional delivery among those who had four or more ANC, and has an effect on the full continuum of maternity care. In studies conducted in Ethiopia, the pro-rich inequalities in maternal health are higher and are, even increasing compared to the previous period [55]. In addition, it is illustrated that in developing countries wealth-related inequalities in utilizing maternal health are overwhelming, especially in Asia and Africa, and yet are higher than inequalities for child vaccination [56, 57].

Another important issue in the completion of maternal health services is the timing of the initiation of the first ANC. Women who initiated the first ANC in the first trimester of pregnancy had more chance of attending all four recommended ANC contacts and completing the continuum of care. It is certain that if a woman starts the first ANC during the early pregnancy stages, she can get sufficient time to attend all the other ANC contacts so that she would have a better chance to complete the continuum. A similar study that was conducted in Kenya reported that women who initiated the ANC contact timely were three times more likely to complete all the recommended maternal health services [58].

On the other hand, the chance of completion of care in this study drops by half for the third child of the household compared to the first child. This finding is in line with what was found in the other three African countries [59]. This could be related to either a woman's encounter with inadequately person-centered care or a disrespectful experience during her prior health facility contacts, which may lead to an unfavorable perception about seeking care at a health facility during pregnancy and childbirth [60,61,62,63]. Alternatively, the women who had prior maternity care at a health facility may have the perception of having the required experience and knowledge to handle the circumstances surrounding pregnancy and childbirth [58].

Limitations of the study

In this study, we used data from the DHS program database on the Ethiopian mini demographic and health survey with a limited number of variables. As a result, we could not recruit as many variables of interest as we intended.

Conclusion and recommendations

Despite the efforts by all stakeholders, the overall completion of the maternity continuum of care is very low in Ethiopia. There was also region-to-region variation, where a higher completion of care in the two city administrations, Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa, and Tigray region. We have also found inequality of service use because of women’s background characteristics like level of education and wealth status. The significant dropout of those pregnant women who received the first ANC contact should alert maternal health program managers to find innovative approaches to retain women in the continuum. Such an approach shall aim to empower women through improved educational experience and economic standing by working with other relevant sectors. Furthermore, awareness creation interventions for the pregnant woman and her family would have the potential to raise early initiation of ANC. Lastly, future research has to investigate the reason behind higher regional variations in the continuum of care .

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available on the DHS program website. [https://www.dhsprogram.com/methodology/survey/survey-display-551.cfm].

Abbreviations

- ANC:

-

Antenatal care

- EA:

-

Enumeration Area

- EDHS:

-

Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey,

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

- LMIC:

-

Low and Middle-Income Countries

- MM:

-

Maternal Mortality

- MMR:

-

Maternal Mortality ratio

- PNC:

-

Post-natal care

References

Organization WH. Newborns: improving survival and well-being. Published 2020. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/newborns-reducing-mortality?__cf_chl_managed_tk__=JuorEwJkfqq8cGycGB6ebOK4V7PG7qzsjGTNC021bYk-1643372917-0-gaNycGzNCaU.

Alkema L, New JR. Global estimation of child mortality using a Bayesian B-spline bias-reduction model. Ann Appl Stat. 2014;8(4):2122–49. https://doi.org/10.1214/14-AOAS768.

Ronsmans C et al. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and when. The Lancet. 2016;368(9542):1189–1200.

Haile D, Kondale M, Andarge E, Tunje A, Fikadu T, Boti N. Level of completion along continuum of care for maternal and newborn health services and factors associated with it among women in Arba Minch Zuria woreda, Gamo zone, Southern Ethiopia: A community based crosssectional study. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6):1–18. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221670.

Bauserman M, Thorsten VR, Nolen TL, et al. Maternal mortality in six low and lower-middle income countries from 2010 to 2018: risk factors and trends. Reprod Health. 2020;17(Suppl 3):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-020-00990-z.

Organization. WH. Trends in Maternal Mortality 2000 to 2017: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division: Executive Summary.; 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/327596.

Tesfaye N. Chinese Government hands over medical supplies to improve newborn health.https://www.unicef.org/ethiopia/press-releases/chinese-government-hands-over-medical-supplies-improve-newborn-health#:~:text=%E2%80%9CThe%20reduction%20of%20newborn%20mortality%20is%20a%20top,live%20births%20in%202019%20to%2021%20in%202024%2F2025.

Document U, Comment USE, To F, Epmm T. Strategies toward ending preventable maternal mortality ( EPMM ). 2015;6736(2013):1-4.

Vargas L, De Felice F, Petrillo A. Editorial journal of multicriteria decision analysis special issue on “Industrial and Manufacturing Engineering: Theory and Application using AHP/ANP.” J Multi-Criteria Decis Anal. 2017;24(5–6):201–2. https://doi.org/10.1002/mcda.1632.

Republic FD. Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Ministry of Health NATIONAL MENTAL. 2015;6(1):16–9.

Consultation W. MINISTRY of HEALTH EN VISIONING ETHIOPIA ’ s PATH TOWAR DS UNIVERSAL HEALTH COVERAGE THROUGH STRENGETHENING PRIMARY HEALTH CARE. Published online 2015:1–128.

Pamela Mitula, Haimanot Ambelu HT. Fewer Maternal Deaths and Stillbirths in Ethiopia: Improving Quality of Care Is Paying Off...; 2019. https://www.afro.who.int/news/fewer-maternal-deaths-and-stillbirths-ethiopia-improving-quality-care-paying.

Panel AP P Brief. Maternal Health. 2010.

Kerber KJ, de Graft-Johnson JE, Bhutta ZA, Okong P, Starrs A, Lawn JE. Continuum of care for maternal, newborn, and child health: from slogan to service delivery. Lancet. 2007;370(9595):1358–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61578-5.

Dadi TL, Medhin G, Kasaye HK, et al. Continuum of maternity care among rural women in Ethiopia: does place and frequency of antenatal care visit matter? Reprod Health. 2021;18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-021-01265-x.

Asratie MH, Muche AA, Geremew AB. Completion of maternity continuum of care among women in the post-partum period: Magnitude and associated factors in the northwest. Ethiopia PLoS One. 2020;15(8 August):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237980.

Ekholuenetale M, Nzoputam CI, Barrow A, Onikan A. Women’s enlightenment and early antenatal care initiation are determining factors for the use of eight or more antenatal visits in Benin: further analysis of the Demographic and Health Survey. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2020;95(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s42506-020-00041-2.

Sserwanja Q, Musaba MW, Mutisya LM, Olal E, Mukunya D. Continuum of maternity care in Zambia: a national representative survey. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2021;21(1):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-04080-1.

Zelka MA, Yalew AW, Debelew GT. Completion and determinants of a continuum of care in maternal health services in Benishangul Gumuz region: A prospective follow-up study. Front Public Heal. 2022;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1014304.

Tizazu MA, Sharew NT, Mamo T, Zeru AB, Asefa EY, Amare NS. Completing the continuum of maternity care and associated factors in debre berhan town, amhara, Ethiopia, 2020. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:21–32. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S293323.

Atnafu A, Kebede A, Misganaw B, et al. Determinants of the continuum of maternal healthcare services in northwest Ethiopia: Findings from the primary health care project. J Pregnancy. 2020;2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4318197.

UNICEF. Ethiopia - Rural Population. https://tradingeconomics.com/ethiopia/rural-population-percent-of-total-population-wb-data.html#:~:text=Rural%20population%20%28%25%20of%20total%20population%29%20in%20Ethiopia,from%20the%20World%20Bankon%20January%20of%202022.%2010Y.

Zelenev S. Towards a “society for all ages”: meeting the challenge or missing the boat. Int Soc Sci J. 2006;58(190):601–16.

Health Facilities Managed by the Public Health Sector. Accessed 27 Jan, 2022. https://ethiopianhealthdata.org/health-facilities.

MoH 2014 Table of Contents Bвeдeниe Fed Democr Repub Ethiop Minist Heal 55 October 2010 1 4.

Demographic and Household Survey Program. The DHS Program - Quality information to plan, monitor and improve population, health, and nutrition programs. The DHS Program. 2022.

DHS. Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019, Sampling. Published 2121. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3946#metadata-sampling.

DHS. Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2019, Data collection. Published 2021. https://microdata.worldbank.org/index.php/catalog/3946#metadata-sampling.

Mohan D, LeFevre AE, George A, et al. Analysis of dropout across the continuum of maternal health care in Tanzania: Findings from a cross-sectional household survey. Health Policy Plan. 2017;32(6):791–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czx005.

Ethiopian Public Health Institute, Research TT and, The TD. IMPROVING ANTENATAL CARE SERVICE UTILIZATION IN ETHIOPIA.; 2016. https://doi.org/10.18356/bf582181-en.

Who. Interventions for Improving Maternal and Newborn Health. World Health. Published online 2009;6:1–6.

USAID. Ethiopia Fact sheet Maternal and Child Health. Nurs Midwifery Board Aust. 2019;035(September):1–3.

Tiruneh GT, Demissie M, Worku A, Berhane Y. Predictors of maternal and newborn health service utilization across the continuum of care in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE. 2022;17(2):e0264612. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0264612.

Eshetu E. Chaka1 2, Mahboubeh, Parsaeian3, Majdzadeh3 R. Factors Associated with the Completion of the Continuum of Care for Maternal, Newborn, and Child Health Services in Ethiopia. Multilevel Model Analysis. Int J Prev Med. 2019;136(19). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6711120/pdf/IJPVM-10-136.pdf.

Emiru AA, Alene GD, Debelew GT. Women’s retention on the continuum of maternal care pathway in west Gojjam zone, Ethiopia: Multilevel analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-020-02953-5.

Sertsewold SG, Debie A, Geberu DM. Continuum of maternal healthcare services utilisation and associated factors among women who gave birth in Siyadebirena Wayu district, Ethiopia: Community-based cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(11):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-051148.

Singh K, Story WT, Moran AC. Assessing the Continuum of Care Pathway for Maternal Health in South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa Kavita. Matern Child Heal. 2016;20(2):281–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-015-1827-6.

Melancon N. EthiopiaNewborns: An Overview of Maternal, Newborn and Child Health in Ethiopia.; 2014. https://www.worldmomsnetwork.com/2014/06/17/field-report-ethiopianewborns-an-overview-of-maternal-newborn-and-child-health-in-ethiopia/.

Foundation M. Launching new Maternal and Newborn Health project in eight new districts in Ethiopia. Published online 2016. https://www.maternity.dk/launching-new-maternal-and-newborn-health-project-in-eight-new-districts-in-ethiopia/.

Iqbal S, Maqsood S, Zakar R, Zakar MZ, Fischer F. Continuum of care in maternal, newborn and child health in Pakistan: Analysis of trends and determinants from 2006 to 2012. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2111-9.

Enos JY, Amoako RD, Doku IK. Utilization, Predictors and Gaps in the Continuum of Care for Maternal and Newborn Health in Ghana. Int J Matern Child Heal AIDS. 2021;10(1):43–53. https://doi.org/10.21106/ijma.425.

Sanogo NA, Yaya S. Wealth Status, Health Insurance, and Maternal Health Care Utilization in Africa: Evidence from Gabon. Biomed Res Int. 2020;2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/4036830.

Tesema GA, Mekonnen TH TA. Individual and community-level determinants, and spatial distribution of institutional delivery in Ethiopia, 2016: Spatial and multilevel analysis. :e0242242. PLoS One. (12;15(11)). 10.1371.

Hailegebreal S, Gilano G, Simegn AE SB. Spatial variation and determinant of home delivery in Ethiopia: Spatial and mixed effect multilevel analysis based on the Ethiopian mini demographic and health survey 2019. PLoS One. 10.1371.

PROJECT, THE BORGEN KH. ADDRESSING THE BARRIERS TO PROPER HEALTH CARE IN ETHIOPIA. https://borgenproject.org/addressing-the-barriers-to-proper-health-care-in-ethiopia/.

Misganaw A, Naghavi M, Walker A, et al. Progress in health among regions of Ethiopia, 1990–2019: a subnational country analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2022;6736(21):1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02868-3.

Dubale T, Mariam DH. Determinants of conventional health service utilization among pastoralists in northeast Ethiopia. Ethiop J Heal Dev. 2007;21(2). https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhd.v21i2.10042.

Ahmed M, Demissie M, Worku A, Abrha A, Berhane Y. Socio-cultural factors favoring home delivery in Afar pastoral community, northeast Ethiopia: A Qualitative Study. Reprod Health. 2019;16(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-019-0833-3.

John Snow I. Reaching Every Sick Child in Pastoralist Areas Integrated Community Case Management in Hamer Woreda. USAID. https://www.pathfinder.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/Reaching-Every-Sick-Child-in-Pastoralist-Areas-Integrated-Community-Case-Management-in-Hamer-Woreda.pdf.

Sara J, Haji Y, Gebretsadik A. Determinants of maternal death in a pastoralist area of borena zone, oromia region, Ethiopia: Unmatched case-control study. Obstet Gynecol Int. 2019;2019. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/5698436.

Tsawe M, Moto A, Netshivhera T, Ralesego L, Nyathi C, Susuman AS. Factors influencing the use of maternal healthcare services and childhood immunization in Swaziland. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0162-2.

Shudura E, Yoseph A, Tamiso A. Utilization and Predictors of Maternal Health Care Services among Women of Reproductive Age in Hawassa University Health and Demographic Surveillance System Site, South Ethiopia: A Cross-Sectional Study. Adv Public Heal. 2020;2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/5865928.

Pintu Paul PC. Socio-demographic factors influencing utilization of maternal health care services in India. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, Lancet. 2020;8(3):666–70 (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2213398420300075).

Rutaremwa G, Wandera SO, Jhamba T, Akiror E, Kiconco A. Determinants of maternal health services utilization in Uganda. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0943-8.

Ricketts TC. Access in health services research: The battle of the frameworks. Nurs Outlooks. 53(6). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2005.06.007.

Gebre E, Worku A, Bukola F. Inequities in maternal health services utilization in Ethiopia 2000–2016: Magnitude, trends, and determinants. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-018-0556-x.

Sanni Yaya BG. Global Inequality in Maternal Health Care Service Utilization: Implications for Sustainable Development Goals. Heal Equity. Published online 2019:145–154. https://doi.org/10.1089/heq.2018.0082.

Howeling TAJ, Ronsmans C, Campbell OMR, Kunst AE. Huge poor–rich inequalities in maternity care: an international comparative study of maternity and child care in developing countries. Bull World Heal Organ. 2007;85(10):745–54.

Kasey Buckles SK. Prenatal investments, breastfeeding, and birth order, Social Science & Medicine. Soc Sci Mediciene. 2014;118:66–70.

Makate M. Maternal health-seeking behavior and child’s birth order : Evidence from Malawi, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. 2016;(72722):1–28. https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/72722/.

Erchafo B, Alaro T, Tsega G, et al. Are we too far from being client centered? PLoS ONE. 2018;13(10):e0205681. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0205681.

Sheferaw ED, Bazant E, Gibson H, et al. Respectful maternity care in Ethiopian public health facilities Prof. Suellen Miller Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0323-4.

Gebremichael MW, Berhane Y, Ababa A, Worku A, Ababa A, Medhanyie AA. Disrespectful Maternity Care Experiences Negatively Influence Future Intention to Use Institutional Delivery in Northern Ethiopia. J Heal Med Nurs. 2020;72(5):1–9. https://doi.org/10.7176/jhmn/72-01.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

There was no funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.B.: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. K.Y.: Conceptualization; Formal analysis; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing. M.W.: Formal analysis; Writing – review & editing. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors analyzed publicly available data obtained from the DHS program database. There was no additional ethical approval sought by the authors.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Birhanu, F., Yitbarek, K. & woldie, M. Client retention in the continuum of maternal health services in Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 569 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09602-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09602-5