Abstract

Background

South Africa had an estimated 7.5 million people living with HIV (PLHIV), accounting for approximately 20% of the 38.4 million PLHIV globally in 2021. In 2015, the World Health Organization recommended the universal test and treat (UTT) intervention which was implemented in South Africa in September 2016. Evidence shows that UTT implementation faces challenges in terms of human resources capacity or infrastructure. We aim to explore healthcare providers (HCPs)’ perspectives on the implementation of the UTT strategy in uThukela District Municipality in KwaZulu-Natal province.

Methods

A qualitative study was conducted with one hundred and sixty-one (161) healthcare providers (HCPs) within 18 healthcare facilities in three subdistricts, comprising of Managers, Nurses, and Lay workers. HCPs were interviewed using an open ended-survey questions to explore their perceptions providing HIV care under the UTT strategy. All interviews were thematically analysed using both inductive and deductive approaches.

Results

Of the 161 participants (142 female and 19 male), 158 (98%) worked at the facility level, of which 82 (51%) were nurses, and 20 (12.5%) were managers (facility managers and PHC manager/supervisors). Despite a general acceptance of the UTT policy implementation, HCPs expressed challenges such as increased patient defaulter rates, increased work overload, caused by the increased number of service users, and physiological and psychological impacts. The surge in the workload under conditions of inadequate systems’ capacity and human resources, gave rise to a greater burden on HCPs in this study. However, increased life expectancy, good quality of life, and immediate treatment initiation were identified as perceived positive outcomes of UTT on service users. Perceived influence of UTT on the health system included, increased number of patients initiated, decreased burden on the system, meeting the 90-90-90 targets, and financial aspects.

Conclusion

Health system strengthening such as providing more systems’ capacity for expected increase in workload, proper training and retraining of HCPs with new policies in the management of patient readiness for lifelong ART journey, and ensuring availability of medicines, may reduce strain on HCPs, thus improving the delivery of the comprehensive UTT services to PLHIV.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Globally there were 38.4 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) at the end of 2021 and 28.7 million were initiated on treatment by the end of December 2021. [1, 2]. South Africa continues to have the largest number of PLHIV with an estimated 7.5 million, accounting for approximately 20% of the 38.4 million PLHIV in the world in 2021 [3, 4]. South Africa has achieved great strides in its response strategies on HIV treatment with the roll-out of ART that has led to a decline in HIV-related mortality rates [5, 6]. South Africa has been reported as having the largest HIV treatment programme in the world [7, 8]. The government has implemented several strategies to curb the disease, including the execution of the comprehensive ART Clinical Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Adults, Pregnancy, Adolescents, Children, Infants and Neonates [9].

In May 2016, following recommendations of the World Health Organization (WHO) [10], the South African government announced the progressive rollout of the universal test and treat (UTT), with an intention to reduce deaths and new infections by 2030 [11, 12]. The 2030 targets included the 95-95-95 targets, which state that 95% of HIV positive people should know their status, 95% of those who know their status should be on treatment and 95% of those on treatment should be virally supressed [13]. UTT advocates that all individuals testing for HIV be initiated on treatment regardless of their clinical staging or CD4 count [14, 15], which is a promising strategy to improve the health of PLHIV [16,17,18,19]. It aims to reduce the incidence of HIV infection through increased HIV testing and provision of immediate access to treatment.

Given the high HIV prevalence in South Africa, the reported benefits of early treatment initiation for PLHIV gives hope of reducing HIV incidence rates. Four large population-based randomized trials of UTT, the population effects of ART to reduce HIV transmission (PopART) [20], Botswana Combination Prevention Project (BCPP) [21], the sustainable East Africa research in community health (SEARCH) [22] and TasP [18, 19], have shown to some degree the benefit of UTT for reducing HIV transmission. For instance, the PopART trial conducted in South Africa and Zambia, which examined the impact of a package of HIV prevention interventions on community-level HIV incidence, showed a significant reduction in new HIV infections [20]. However, not all these trials have shown impact on reducing HIV incidence.

Despite the importance of UTT, evidence shows that the implementation of UTT in South Africa faces challenges such as increased non-retention rates [23,24,25], increased workload [24], leading to inadequate human resource [18, 26], and challenges with infrastructure [26, 27], human resources capacity and infrastructure [18, 24, 26, 28, 29]. Other potential barriers include psychosocial and health systems factors [27, 30], such as shortages of drugs [31, 32], long patient waiting times [33], leadership and governance [29], competing clinical care priorities [34], communication breakdown between HCPs and patients [35], insufficient skill and inadequate supervisory support [29]. These could have negative impacts on the effective implementation of UTT.

Healthcare providers (HCPs) are key players in the implementation of UTT in the health facilities [36, 37]. They are the ambassadors of the national Department of Health (NDoH) in advocating for the new HIV treatment guidelines particularly in terms of communicating new guidelines to those diagnosed with HIV. To identify the health system gaps, it is therefore important to understand how HCPs navigate the new changes and impacts to their health service delivery. In this study, we aimed to explore HCPs’ perspectives on the implementation of UTT in the uThukela district, KwaZulu-Natal province.

Materials and methods

Study design and setting

A qualitative study design approach was followed to understand the perceptions and experiences of HCPs on the implementation of the UTT strategy. The study was conducted in the uThukela District Municipality (DM) in KwaZulu-Natal (KZN), South Africa. uThukela DM is a predominantly rural district with high HIV prevalence of 22.4% [38] and shares its western border with the country of Lesotho. The district is comprised of three local municipalities (LMs) namely Alfred Duma LM, Inkosi Langalibalele LM and Okhahlamba LM.

Universal Test and Treat in the uThukela DM is implemented and delivered through multiple modalities of differentiated treatment delivery models. However, in the 18 facilities selected for this study (Table 1), UTT is delivered mainly through the facility-based and community-based models, which are integrated with other services such as those for patients with non-communicable diseases [39]. The facility-based model consists of HCP-led group of patients who meet regularly at the facility to receive health education, health screenings, adherence support, peer support, and collect ART; while the community outreach model, which are also nurse-led, provide both clinical care and medications at offsite areas in the community as an extension of the clinic (mobile clinics). In addition to the support provided by HIV counsellors, the use of case managers, linkage officers, and nurse clinicians have become critical in providing support to individuals diagnosed with HIV, in so far as complementing the initial counselling services provided by counsellors. These differentiated service delivery models have the potential to increase retention in care and adherence to medication among people living with HIV [40].

Conceptual framework

To analyse HCPs’ experience and perceptions providing HIV care under the UTT strategy, an adapted version of the framework for a systems approach to healthcare delivery (FSAHD) [41] was used. This four-level model of the health care system consists of (a) individual patient (the service users); (b) the care team or frontline workers, i.e., HCPs, patients’ family members and other care givers; (c) the organization that provides the infrastructure and resources for care such as hospital, clinic, and nursing home. The fourth level in this model is the political and economic environment such as the public and private regulator, insurers, healthcare purchasers, research funders that influence the structure and performance of health care. For analysis purposes, this study will only focus on the first three levels.

Key informant interview procedures

A sample of 161 HCPs were purposively selected from 18 health facilities and three sub-districts, based on their experience implementing the UTT programme (Table 1). These consisted of at least two HPCs from each available cadres comprising of Managers (facility managers and PHC manager/supervisors); Nurses (enrolled, auxiliary, and professional Nurses) and Lay workers (lay counsellors, community health workers, linkage officers).

Data collection procedure

An open-ended questionnaire adapted from Hoffman et al., 2015 [42] was used to collect qualitative data from HCPs. This structured interview included data on demographic characteristics, work experience and HCPs’ perceptions on the implementation of UTT. Participants were approached by trained interviewers and depending on availability, an appointment was secured in order not to disrupt the daily functioning of the health facilities. In most instances the interview, which lasted between 20 and 105 minutes, was conducted over more than one visit depending on the availability and time constraints of the individual. The interviews were audio recorded, and simultaneously captured into REDCap by the interviewers to reduce the time spent on transcriptions.

Each respondent had a unique code, e.g., BISC-EN-M, which are added at the end of each quote to provide context. The first initial letters describe the facility area and the type (i.e., primary clinic, mobile clinic etc.), followed by participants’ job category (e.g., enrolled nurse - EN) and gender (F/M) at the time of the interview.

Data management and analysis

The recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim and updated in REDCap and exported to Excel. The analysis team, which comprised of three members (EN, VM, NAJ), independently read through all the transcripts to gain a general understanding of the content and scope, and discussed initial emerging themes used to develop a structured coding framework. Coded information was linked to broader emerging themes across interviews. Data from HCP interviews were coded independently using ATLAS.ti v8 software. Comparative analysis between two skilled qualitative researchers was performed to ensure analysis accuracy. The analysis process was informed by the interview questions, literature, and the inductive approach to the data.

Results

Of the 161 HCPs included in this study, 41% (66) were from Alfred Duma local municipality where eight of the 18 health facilities are located (Table 2). The study consisted of 97.5% (n = 157) Black African participants, of which 88.2% (142) were female, and most 90% (145) had obtained a tertiary level of education. While a fifth of the participants (33) were professional nurses, most participants (98.1%, 158) were employed in a public clinic setting (Table 2).

Perceptions on the implementation of UTT

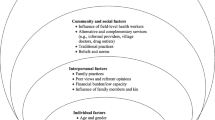

Several themes relating to HCPs’ perceptions on the implementation of UTT were identified and classified under three levels according to the adapted framework for a systems approach to healthcare delivery (FSAHD) [41] i.e., health service users (patients), healthcare providers and health system (Fig. 1). Thirteen themes emerged from the data and are presented in detail with illustrative quotes.

Perception of UTT on service users

Almost all interviewed HCPs reported positive effects of UTT on service users, such as helping the patients to live longer and healthier. These were some of the themes that emerged:

Good quality of life and immediate initiation in care

The general perception among HCPs was that UTT provided people living with HIV (PLHIV) the opportunity to have a good quality of life through immediate access to prevention and care services, which potentially increases early retention in care and adherence to medication.

“It [UTT] has given them [PLHIV] the opportunity to easy access to treatment and services. It has prevented unnecessary sickness.” (BNHC005_PN_F)

“It [UTT] is a good impact, people are getting primary prevention, they are getting treatment early, which prevents other diseases from manifesting.” (KEMG012_PN_F)

“It [UTT] doesn’t get to a stage where someone is very sick, early treatment is helping them out.” (KEMG002_EN_F)

Increased life expectancy

Most of the participants agree that the implementation of UTT has led to increased life expectancy among PLHIV, with more people living a healthy life.

“Good impact because they now live longer, and the stigma percentage have dropped.” (KEMP008_EN_F)

“It [UTT] has a very positive impact because they start treatment while the CD4 count is still alright, which reduces the number of infections; people live longer and are protected.” (DIGC002_LC_F)

“It [UTT] has increased life expectancy and more patients are living a healthy life.” (DIGC005_PN_F)

Reduced clinic process time

Narratives also suggest that the time spent by patients accessing care in the clinics has reduced and that clinics are not as congested as were the case pre-UTT. Participants attributed the reduced waiting time and reduced congestion at clinics to the implementation of the UTT strategy.

“It [UTT] has reduced the waiting period of patients at the clinic, because people are being quickly treated which reduces the number of people coming to the clinic.” (BNHC011_EN_F)

“It [UTT] has also made things easy for patients, because they come once a month to fetch treatment, after they have been diagnosed with HIV and also everything (initiating, HIV classes and taking bloods) is done on the same day, patient doesn’t have to keep on coming back to do all these things on a weekly basis.” (KB2M002_LC_F)

Perception of UTT on healthcare providers

HCPs expressed different views on the effects the new UTT intervention has on them. While majority of participants reported on the negative effects of UTT on HCPs, there were some positive effects. These include increased workload, increased defaulters, physiological and psychological impacts, improved processes at the facilities, better patient management, and human resources.

Increased defaulters and workload

One of the major challenges reported by the HCPs was that UTT implementation increased patient defaulter rates due to patients’ unreadiness to initiate ART. HCPs expressed that UTT creates a high number of ART defaulters, which is believed to have been caused by overwhelming feeling of starting a lifelong treatment immediately after diagnosis. According to the participants, some patients are not ready to start treatment since they are yet to accept their new HIV status, and as such would like some time to process the new reality of living with HIV. However, because they respect health care workers, they go along with the same day initiation post HIV positive diagnosis and some never get retained in care.

“I feel like it [UTT] creates a lot of defaulters, because most people who test positive before they accept their status, ...are given treatment which they take just to please you as a health care worker, while they are not ready to take treatment; so, they just take it once off and never come back.” (DLHC001_CM_F)

“…It [UTT] also have some disadvantages which is that we initiate them [HIV patients] same day assuming they are ready to start, yet they have not accepted [the new status] and they never come back and sometimes they provide incorrect information and when tracing them we never find them.” (ECHC008_PN_F)

Healthcare providers reported that the increased volume of defaulters is one of the reasons for increased workload causing a greater burden on them. The other reason for the increased workload reported by the HCPs was that UTT process is long, and counsellors have to provide all necessary services to patients in one session.

“More work as counsellors have to do everything in one session with clients.” (BISC008_CHW_F)

“More work for them as they have to account also for patients, why they did not start ART.” (BISC006_CHW_F)

“The level of work has increased because they [HCPs] have to do post counselling, initiating, doing baseline bloods.” (DIGC006_NA_F)

However, other HCPs saw the increase in workload as a good opportunity to improve the processes in the facilities. They stated that:

“There is more paperwork, but the good side is that health care workers get a chance to do everything with the client in one session.” (BISC005_PN_F)

“It [UTT] has created more work which has a good impact because that has cut out unnecessary delays.” (BNHC003_LC_F)

Physiological and psychological impacts

Another negative side of UTT is the effect it has on the well-being of HCPs, which include some physiological and psychological impacts such as stress and burnout. One clinic manager and professional nurse highlighted issues of burnout and being overworked. Others highlighted issues around feeling under pressure and stressed.

“Burnout on staff” (BISC004_CM_F)

“It [UTT] has created a lot of stress and demand due to targets that has to be met.” (BNHC005_PN_F)

“UTT has made working easy but there is so much pressure ….” (BISC009_EN_F)

Better patient clinical management

Some clinic managers expressed several benefits of UTT on patient clinical management, while others commented on the advantage of UTT as it has improved the clinic flow and operations. HCPs felt that the introduction of UTT has improved patient management and care compared to the old HIV guidelines. Mostly because they do not have to treat very sick patients since UTT promotes same-day initiation after diagnosis.

“[UTT] has many benefits and avoids clients coming constantly to facility and decreases mortality rate. Clients also feel welcome in clinic because they immediately receive medication.” (ELSG015_CM_F)

“It [UTT] is good because before UTT people had to go and come back the next day to do baseline bloods and they would not come back again. But now with UTT people start treatment and take bloods on the day they are diagnosed.” (DLHC005_EN_F)

“Getting to sit clients in one session and go through everything is better than breaking into several sessions.” (UCSC004_EN_F)

Human resources

In some of the facilities, the implementation of UTT is reported to have improved the skills of HCPs through the trainings provided to them. Also, HCPs reported that more manpower have been hired in some facilities to help ease the workload.

“Personnel has been hired. Less money spent on minor ailments.” (PMSA1_CL_F)

“Yes, this is because us as health care providers were given training on HIV testing and treatment.” (KEMG005_EN_F)

Perception of UTT on the organization of care in the health system

Participants expressed different views about the effect of UTT on care organization in the health system. They mostly highlighted how the implementation has assisted in decreasing the burden on the health system and helped to attain the NDoH goals of having more individuals linked to care and the provision of immediate access to treatment, to reduce the incidence of HIV infection. These were some of the themes which emerged:

Increased number of patients initiated

There was a consensus among HCPs that the UTT strategy has led to an improvement in the number of PLHIV who initiated care and are started on treatment.

“It [UTT] has increased the number of people getting tested and getting medication soon after they are tested positive.” (ESVC007_CHW_F)

“It [UTT] has increased the stats numbers for people initiated on medication.” (ECHC014_EN_F)

Decreased burden on the system

Participants claimed that because of the implementation of the UTT strategy, hospitals no longer experience high admissions and high rates of lost to follow-up of PLHIV due to fewer people getting sick, and the absence of the prescribed pre-antiretroviral therapy services, such as counselling, and clinical staging.

“[UTT] reduced the number of admissions because clients do not get sick.” (KEMP007_EN_F)

“[UTT] reduced the number of lost to follow-up because they don’t do pre-ART anymore.” (DIGC011_EN_F)

“Many people start treatment before they would get sick, therefore less people are admitted to the hospital for HIV.” (UECG007_EN_F)

Reaching NDoH targets

The main purpose of implementing the UTT strategy was to reduce the incidence of HIV infection through increased HIV testing and provision of immediate access to treatment to PLHIV. Achieving this require the attainment of certain targets. Participants asserted that UTT has increased the number of PLHIV retained in care and are virally suppressed.

“It [UTT] has increased the numbers of people who are on treatment for HIV which has improved the 90-90-90 programme.” (ECHC007_HM_F)

“It [UTT] has helped us know the number of people tested positive, initiated, with suppressed viral loads and to reach the 90-90-90.” (ESVC006_LO_F)

“It [UTT] has increased the number of people getting tested and getting medication soon after they are tested positive.” (ESVC007_CHW_F)

Financial aspects and stakeholder involvement

Other concerning challenges highlighted by the participants include the need for more medical stocks (ARVs) as the number of patients being initiated on ART increases. In some facilities, HCPs voiced their concern about ARV stock-outs and the increased financial burden that comes with purchasing more ARVs. This is further linked to the lack of involvement of stakeholders (i.e., health care facility managers) in the decisions to implement UTT in under-resourced facilities. Unhappy feelings were expressed by most HCPs on the processes followed to implement UTT. They mentioned not being part of the decision-making team, and highlighted gaps in the UTT implementation processes such as the absence of piloting UTT and the provision of training on some of the processes that were adopted. These were their views:

“The drugs [ARVs] are running out.” (DIGC006EN_F)

“The money spent on ART is increasing.” (DIGC010_EN_F)

“I feel that we were not involved as people on the ground level; they [policy makers] didn’t consult with us when they were deciding on it [UTT]. So, the only people who were involved were people from the national level and we were not consulted before its implementation as well but were instructed to implement it.” (ESVC001_CM_F)

Discussion

South Africa has invested so much in upscaling the UTT strategy with the hopes of improving linkage to and retention in care among PLHIV [16,17,18,19]. This study, which aimed to explore HCPs’ perspectives on the implementation of UTT, is one of the very few conducted amongst South African healthcare providers to understand their views and perceptions about the implementation of UTT. Findings from this study highlight the perceived influence of implementing UTT on service users, on healthcare providers, and on the health system in the uThukela DM in KwaZulu-Natal province, South Africa. Our study reveals a general acceptance by healthcare providers of the implementation of the UTT strategy, which came with the understanding that HIV-positive clients will have a better chance of living longer if they are immediately started on treatment. Clinical benefits were also seen as a positive outcome of the implementation of UTT as the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets were met. In some facilities, enrolled nurses and clinic managers commented on the advantage of implementing UTT as it has improved the clinic flow and operations. These positive views on the implementation of UTT were similarly found in other studies [23, 27]. The acceptance from HCPs who are in the frontline and advocates of the new UTT policy guidelines gives hope that South Africa is on the right direction towards improved rates of HIV testing, linkage to care, and viral load suppression.

Furthermore, HCPs highlighted the positive influences UTT has on the quality of life of patients. They also mentioned that UTT reduced congestion and waiting times at clinics and therefore making clinic flows better for patient satisfaction. Similar findings were reported in other studies where HCPs emphasized patients’ health benefits resulting from the implementation of UTT [27, 43, 44].

The main disadvantage highlighted by HCPs was that UTT might cause an increase in patient defaulters, as some patients may not be ready to immediately initiate treatment [45]. HCPs reported that the increased volume of defaulters has led to a surge in their workload since the implementation of UTT. The challenges about increased workload have been reported in other studies as well [24, 46, 47], and may undermine the quality of care provided by healthcare workers. Improved counselling strategies are needed in these facilities to reduce the number of defaulters caused by overwhelmed patients [26]. One of the crucial aspects of providing quality health care is proper training of HCPs [48], and this could be undermined by the lack of skills and training, and staff shortages. Health system strengthening such as providing more capacity and capability might decrease the already over-burdened system, and thus improve the delivery of the comprehensive UTT services to PLHIV [49]. This study show that training provided to HCPs on the implementation of UTT were insufficient. These issues have been highlighted in other studies [25,26,27,28,29, 47]. Findings from Plazy and colleagues [26] favoured the move from the use of few experienced nurses to an integrated model of care, with a workforce trained in the Nurse Initiated Management of Antiretroviral Therapy (NIMART) [50], who have counselling skills. Other studies support the provision of differentiated service delivery models that have the potential to increase the retention in care rates and adherence to medication among people living with HIV [39, 40].

Another disadvantage of the UTT strategy reported by HCPs includes poor consultation from the National Department of Health on the implementation of the UTT. This may have led to the gaps mentioned by some facility managers, such as insufficient training for HCPs [18] as some of their responses were not in line with the UTT guidelines. To strengthen health system and provide effective UTT services, there is a need to explore better mechanisms to ensure that adequate information is available to HCPs, and that they are provided with the necessary training to offer comprehensive UTT services [27]. The crucial importance of retraining HCPs with new policies can never be over stressed if there must be adequate health workforce to deliver UTT services [18, 26].

This study shows that UTT has led to increased number of patients being tested and immediately initiated on treatment. It is concerning to note that this increase translates to more required medical stocks and that some facilities experience ARV stock-outs and increased financial burden that comes with purchasing more ARVs. Shortages of ARVs can be a barrier in effective implementation of UTT as it means that patients may not be immediately initiated on treatment, and this could have a negative impact on the attainment of the 95-95-95 targets. Shortages of treatment has been reported in at least one out of three facilities in South Africa [18, 31, 32, 51]. For the success of the UTT policy, it is suggested that the NDoH engage fully with stakeholders to ensure that under-resourced facilities are provided with the necessary health equipment and training to enable HCPs offer comprehensive UTT services.

Study Limitations

A limitation of this study is that most interviews were conducted in clinics, which might have caused discomfort and led to socially desirable responses. However, interviewers were well trained in managing these issues. Results from this study may not be generalizable as the study included a small sample from a single district in KZN province, which may be different from the other eight provinces in South Africa.

Conclusion

Our results highlight important gaps in the implementation of UTT in a high HIV burden district in South Africa. There is a need for policy makers to engage with facility managers around elements such as infrastructure, human resources, and financial capacity which are crucial in providing a comprehensive UTT programme. For a country such as South Africa, health system level interventions like UTT would need to also focus on clinic readiness in terms of providing patients with the necessary and effective health services such as proper counselling care and psychological assistance to manage their HIV status. This includes proper training for the counsellors to be able to provide appropriate counselling care in the management of patient readiness for the lifelong ART journey. Other health system interventions such as ensuring availability of medicines based on the expected demand, and adequate human resources for the expected increase in workload, could reduce strain on HCPs. This would improve and increase the number of patients who link to care and remain in care, and thus meet the 95-95-95 targets.

More studies are needed on the acceptability of UTT by health care workers in South Africa. Furthermore, for the success of the UTT policy, we recommend that the NDoH engage fully with stakeholders including HCPs to ensure that they are provided with the necessary training to offer comprehensive UTT services. The importance of retraining HCPs with new policies can never be over stressed if there must be adequate health workforce to deliver UTT services.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

UNAIDS. AIDSinfo Data Sheet 2021. 2021. https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/ Accessed January 2023.

UNAIDS, Fact sheet. 2022. 2022. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/UNAIDS_FactSheet_en.pdf Accessed January 2023.

Simbayi LC, Zuma K, Zungu N, Moyo S, Marinda E, Jooste S, Mabaso M, Ramlagan S, North A, van Zyl J, Mohlabane N, Dietrich C, Naidoo I, the SABSSM V Team. South african National HIV Prevalence, incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2017. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2019.

SANAC. 2018, Republic of South Africa 2018 global AIDS monitoring report, https://sanac.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Global-AIDS-Report-2018.pdf. Retrieved July 2021

Bor J, Herbst AJ, Newell ML, et al. Increases in adult life expectancy in rural South Africa: valuing the scale-up of HIV treatment. Science. 2013;339:961–5.

Mee P, Collinson MA, Madhavan S, et al. Determinants of the risk of dying of HIV/AIDS in a rural south african community over the period of the decentralised roll-out of antiretroviral therapy: a longitudinal study. Glob Health Action. 2014;20:24826.

Simelela NP, Venter WD. A brief history of South Africa’s response to AIDS. S Afr Med J. 2014;104(3 Suppl 1):249–51.

Venter WDF. A South African decade of antiretrovirals. S Afr Med J. 2014;104(1):3.

South African National Department of Health (NDoH), 2019. ART Clinical Guidelines for the Management of HIV in Adults, Pregnancy, Adolescents, Children, Infants and Neonates. https://www.knowledgehub.org.za/elibrary/2019-art-clinical-guidelines-management-hiv-adults-pregnancy-adolescents-children-infants. Retrieved 14 Dec 2021

World Health Organization. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva. ; 2015.13. UNAIDS. Fast Track: Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030: UNAIDS; 2014 [Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/JC2686_WAD2014report.

Perriat D, Balzer L, Hayes R et al. Comparative assessment of five trials of universal HIV testing and treatment in sub-Saharan Africa.J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(1)

Onoya D, Sineke T, Hendrickson C, et al. Impact of the test and treat policy on delays in antiretroviral therapy initiation among adult HIV positive patients from six clinics in Johannesburg, South Africa: results from a prospective cohort study. BMJ Open. 2020;10:e030228.

UNAIDS. Fast Track: Ending the AIDS epidemic by 2030.: UNAIDS. ; 2014 [Available from: http://www.unaids.org/en/resources/documents/2014/JC2686_WAD2014report.

South African National Department of Health (NDoH). Final draft. In: Africa DoHS, editor. Natinoal Policy on HIV Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) and test and treat (T&T). Pretoria: NDoH; 2016.

Girum T, Yasin F, Wasie ST, Bekele F, Zeleke B. The efect of “universal test and treat”program on HIV treatment outcomesand patient survival among a cohort of adults taking antiretroviral treatment (ART) in low income settings of Gurage zone, South Ethiopia. AIDS Res Ther. 2020;17(19). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-020-00274-3.

Grinsztejn B, Hosseinipour MC, Ribaudo HJ, et al. Effects of early versus delayed initiation of antiretroviral treatment on clinical outcomes of HIV-1 infection: results from the phase 3 HPTN 052 randomised controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:281–90.

National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services. Starting antiretroviral treatment early improves outcomes for HIV-infected individuals [news release]. https://www.nih.gov/news-events/news-releases/starting-antiretroviral-treatment-early-improves-outcomes-hiv-infected-individuals. Published May 27, 2015.

Boyer S, Iwuji C, Gosset A, Protopopescu C, Okesola N, Plazy M et al. Factors associated with antiretroviral treatment initiation amongst HIV-positive individuals linked to care within a universal test and treat programme: early findings of the ANRS 12249 TasP trial in rural South Africa. AIDS care. 2016;28 Suppl 3:39–51. Epub 2016/07/16. pmid:27421051

Iwuji CC, Orne-Gliemann J, Larmarange J, Balestre E, Thiebaut R, Tanser F, et al. Universal test and treat and the HIV epidemic in rural South Africa: a phase 4, open-label, community cluster randomised trial. Lancet HIV. 2018 Mar;5(3):e116–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(17)30205-9. Epub 2017 Nov 30. PMID: 29199100.

Hayes RJ, Donnell D, Floyd S, Mandla N, Bwalya J, Sabapathy K, et al. Effect of Universal Testing and Treatment on HIV incidence - HPTN 071 (PopART). N Engl J Med. 2019;381:207–18.

Makhema J, Wirth KE, Pretorius Holme M, Gaolathe T, Mmalane M, Kadima E, et al. Universal testing, expanded treatment, and incidence of HIV infection in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(3):230–42.

Chamie G, Kamya MR, Petersen ML, Havlir DV. Reaching 90-90-90 in rural communities in East Africa: lessons from the Sustainable East Africa Research in Community Health Trial. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2019 Nov;14(6):449–454. PMID: 31589172; PMCID: PMC6798741. https://doi.org/10.1097/COH.0000000000000585.

Onoya D, Hendrickson C, Sineke T, Maskew M, Long L, Bor J, et al. Attrition in HIV care following HIV diagnosis: a comparison of the pre-UTT and UTT eras in South Africa. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 2021;24(2):e25652. Epub 2021/02/20. pmid:33605061

Kimanga DO, Oramisi VA, Hassan AS, Mugambi MK, Miruka FO, Muthoka KJ et al. Uptake and effect of universal test-and-treat on twelve months retention and initial virologic suppression in routine HIV program in Kenya.PLoS One. 2022 Nov22;17(11):e0277675. doi: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0277675. PMID: 36413522; PMCID: PMC9681077.

Stafford KA, Odafe SF, Lo J, Ibrahim R, Ehoche A, Niyang M et al. Evaluation of the clinical outcomes of the Test and Treat strategy to implement Treat All in Nigeria: Results from the Nigeria Multi-Center ART Study. PloS one. 2019;14(7):e0218555. Epub 2019/07/11. pmid:31291273

Plazy M, Perriat D, Gumede D, Boyer S, Pillay D, Dabis F, et al. Implementing universal HIV treatment in a high HIV prevalence and rural south african setting—field experiences and recommendations of health care providers. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(11):e0186883.

Onoya D, Mokhele I, Sineke T, et al. Health provider perspectives on the implementation of the same-day-ART initiation policy in the Gauteng province of South Africa. Health Res Policy Sys. 2021;19:2.

Orange E. Assessing health policy implementation in South Africa: case study of HIV universal test and treat. Washington 2018. https://digital.lib.washington.edu/researchworks/handle/1773/41715

Mnyaka OR, Mabunda SA, Chitha WW, Nomatshila SC, Ntlongweni X. Barriers to the Implementation of the HIV Universal Test and Treat Strategy in Selected Primary Care Facilities in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province.J Prim Care Community Health. 2021 Jan-Dec;12:21501327211028706. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/21501327211028706. PMID: 34189991; PMCID: PMC8252362.

Nansseu JRN, Bigna JJR. Antiretroviral therapy related adverse effects: can sub-saharan Africa cope with the new “test and treat” policy of the World Health Organization? Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40249-017-0240-3.

Hodes R, Price I, Bungane N, Toska E, Cluver L. How front-line healthcare workers respond to stock-outs of essential medicines in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2017;107(9):738–40.

Ankomah A, Ganle JK, Lartey MY, et al. ART access-related barriers faced by HIV-positive persons linked to care in southern Ghana: a mixed method study. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16(1):738.

Rosen S, Fox MP, Larson BA, et al. Accelerating the uptake and timing of antiretroviral therapy initiation in Sub-Saharan Africa: an operations research agenda. PLoS Med. 2016;13(8):e1002106.

Bassett IV, Regan S, Luthuli P, et al. Linkage to care following community-based mobile HIV testing compared with clinic-based testing in Umlazi Township, Durban, South Africa. HIV Med. 2014;15(6):367–72.

Govindasamy D, Ford N, Kranzer K. Risk factors, barriers and facilitators for linkage to antiretroviral therapy care: a systematic review. AIDS. 2012 Oct 23;26(16):2059-67. Doi: https://doi.org/10.1097/QAD.0b013e3283578b9b. PMID: 22781227.

Chen L, Evans T, Anand S, Boufford JI, Brown H, Chowdhury M, et al. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet. 2004;364(9449):1984–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17482-5.

Van Damme W, Kober K, Kegels G. Scaling-up antiretroviral treatment in southern african countries with human resource shortage: how will health systems adapt? Soc Sci Med. 2008;66(10):2108–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.043.

Cooperative governance and traditional affairs (COGTA). PROFILE: UTHUKELA DISTRICT MUNICIPALITY. https://www.cogta.gov.za/ddm/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Uthukela-October-2020.pdf. Retrieved 14 December 2021.

Duffy M, Sharer M, Davis N, Eagan S, Haruzivishe C, Katana M, Makina N, Amanyeiwe U. Differentiated antiretroviral therapy distribution models: enablers and barriers to universal HIV treatment in South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe. J Assoc of Nurses AIDS Care. 2019 Sep-Oct;30(5):e132-e143. https://doi.org/10.1097/JNC.0000000000000097

Fox MP, Pascoe S, Huber AN, et al. Adherence clubs and decentralized medication delivery to support patient Retention and sustained viral suppression in Care: results from a cluster randomized evaluation of differentiated ART delivery models in South Africa. PLOS Med. 2019;16:e1002874.

National Academy of Engineering (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Engineering and the Health Care System; Reid PP, Compton WD, Grossman JH, et al., editors. Building a Better Delivery System: A New Engineering/Health Care Partnership. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US) et al. ; 2005. 2, A Framework for a Systems Approach to Health Care Delivery. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK22878/?log$=activity

Hoffman S. Linkage to HIV Care in South Africa: Qualitative and Quantitative Findings from Pathways to Care.Columbia University.

Dovel K, Phiri K, Mphande M, et al. Optimizing test and treat in Malawi: health care worker perspectives on barriers and facilitators to ART initiation among HIV-infected clients who feel healthy. Glob Health Action. 2020;13:1728830.

Pell C, Reis R, Dlamini N, Moyer E, Vernooij E. 2019, ‘Then her neighbour will not know her status’: how health providers advocate antiretroviral therapy under universal test and treat, International Health, Volume 11, Issue 1, January 2019, Pages 36–41, https://doi.org/10.1093/inthealth/ihy058

Evans C, Bennett J, Croston M, Brito-Ault N, Bruton J. In reality, it is complex and difficult”: UK nurses’ perspectives on “treatment as prevention” within HIV care. AIDS Care. 2015;27(6):753–7. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.1002826.

Songo J, Wringe A, Hassan F, et al. Implications of HIV treatment policies on the health workforce in rural Malawi and Tanzania between 2013 and 2017: evidence from the SHAPE-UTT study. Glob Public Health. 2021;16:256–73.

Laar AS, Dalinjong PA, Ntim-Adu C, Anaman-Torgbor JA et al. Understanding health facility challenges in the implementation of option B + guidelines in Ghana: the perspectives of health workers.J Hosp Manag Health Policy2:29–37.

Luxford K, Safran DG, Delbanco T. Promoting patientcentered care: a qualitative study of facilitators and barriers inhealthcare organizations with a reputation for improving the patient experience. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011;23(5):510–5.

Barnighausen T, Bloom DE, Humair S. Human Resources for treating HIV/AIDS: are the Preventive Effects of Antiretroviral Treatment a game changer? PLoS ONE. 2016;11(10):e0163960. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0163960.

Zuber A, McCarthy CF, Verani AR, Msidi E, Johnson C. A survey of nurse-initiated and -managed antiretroviral therapy (NIMART) in practice, education, policy, and regulation in east, central, and southern Africa. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2014;25(6):520–31.

Hodes R, Price I, Bungane N, Toska E, Cluver L. How frontline healthcare workers respond to stock-outs of essential medicines in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. S Afr Med J. 2017;107(9):738–40.

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend our word of appreciation to the uThukela district manager, Dr T. Zulu as well as the deputy district manager of monitoring and evaluation, Mr. M. Asvat for their unending support to the project. We also appreciate the co-operation of the staff in the selected facilities for participating in this study, and would like to thank Ms T. Makowa, and the fieldwork team for data collection.

Funding

This research has been supported by the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) through the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), under the terms of Cooperative Agreement Number 1U2GGH001150.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EN conceived and implemented the study design, modified the data collection instruments, conducted, and transcribed the interviews, performed data analysis and interpretation, drafted, and revised the manuscript. DB contributed to the study design, data analysis and interpretation, revised the instruments and the manuscript, while VM, NAJ, and WB contributed to data analysis, interpretation and revised the manuscript. In addition, VM contributed to the initial drafting of the manuscript, DP contributed to data collection, and MH provided critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) ethics committee in October 2017 (EC021-7/2016). It was also reviewed in accordance with US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) human research protection procedures and was determined to be research, but CDC investigators did not interact with human subjects or have access to identifiable data or specimens for research purposes. Additional approval was received from the KZN provincial Department of Health and uThukela district municipality in October 2017. Informed consent was obtained from all participants before participating in the study. Confidentiality and privacy were maintained using study pseudonyms instead of healthcare providers’ personal details in all our records. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations in Ethics Approval and Consent to participate.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official position of the funding agencies.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

We declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Nicol, E., Mehlomakulu, V., Jama, N.A. et al. Healthcare provider perceptions on the implementation of the universal test-and-treat policy in South Africa: a qualitative inquiry. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 293 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09281-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09281-2