Abstract

Background

Community pharmacists actively engage in managing the health of local residents, but the COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated rapid adaptations in practice activities.

Objectives

We sought to identify the specific adaptations in practice and the expanded roles of community pharmacists in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of published studies reporting the tasks of pharmacists in community pharmacies or who were involved in pharmacy practices addressing the pandemic. Two investigators independently searched PubMed (December 2019–January 2022) for eligible articles. We conducted a meta-analysis to measure the frequencies of practical activities by pharmacists in response to COVID-19.

Results

We identified 30 eligible studies. Meta-analysis of these studies found that the most commonly reported adaptation in pharmacist practice activities was modifying hygiene behaviors, including regular cleaning and disinfection (81.89%), followed by maintaining social distance from staff and clients (76.37%). Educating clients on COVID-19 was reported by 22 studies (72.54%). Telemedicine and home delivery services were provided to clients by 49.03 and 41.98% of pharmacists, respectively.

Conclusions

The roles of community pharmacists in public health activities have adapted and expanded in response to COVID-19, notably by incorporating public health education activities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

As of 3 July 2022, the cumulative numbers of COVID-19 of cases and deaths worldwide have exceeded 546 million and 6.3 million, respectively [1]. Although the rates of COVID-19 infections and deaths have begun to decrease globally, the number of infections and deaths continues to grow in some countries and regions [1].

Pharmacists working in community pharmacies are known to support community health care as the first healthcare providers for community residents, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic [2]. In fact, our previous study indicated that many community pharmacists in Japan often provided the initial COVID-19-related consultations during the early phases of pandemic [3]. Several studies reported that in response to COVID-19, in addition to supplemental hygiene activities such as regular cleaning and disinfection of the pharmacy [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13], community pharmacists were required to provide public health education to the community [14], and other various public health services such as home delivery services to clients [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11] and remote explanation of medications [10, 12, 15,16,17,18,19].

Understanding the adaptations in pharmacists’ practice during the COVID-19 pandemic is crucial to strengthening the role of pharmacists as health partners to the community and for developing effective countermeasures to COVID-19 and potential future infectious disease pandemics. Previous reviews have mentioned the potential for community pharmacists to play an important role in the COVID-19 pandemic by taking on a variety of new roles that complement their existing work [20,21,22]. However, no comprehensive, systematic review and meta-analysis focusing on pharmacists’ practice during the era of the COVID-19 pandemic has been conducted.

The purpose of the present study is to examine the adaptations to the practice of community pharmacists in response to COVID-19 conditions, and how these adaptations contributed to public health and infection preventions, in an effort to provide an evidence base for discussing the role of pharmacists in future pandemics due to emerging infectious diseases.

Methods

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement and the statement by the Meta-analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (MOOSE) group [23, 24] (see Additional file 1).

Eligibility criteria and outcome measures

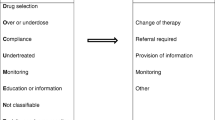

Studies from the PubMed database fulfilling the following selection criteria were included in the meta-analysis: (1) randomized clinical trials, observational studies, letters and commentaries in the IMRD (introduction, methods, results, discussion) format written in the English language; (2) with a study population of pharmacists or others involved in pharmacy practices regarding COVID-19; (3) with primary outcomes of practical activities performed by pharmacists for COVID-19; (4) with outcome variables of pharmacy practices regarding COVID-19 in categories of drug and information delivery, client education, regular cleaning and disinfecting, and structural ingenuity; and (5) with any secondary outcome variable. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies of practical activities such as equipment and disinfection to protect individual pharmacists; (2) studies without reporting of outcome variables; and (3) studies with insufficient or incomplete data. We selected all reported outcome variables from the extracted papers and selected same reported variables in these reports as the outcome variables in the present study.

The main focus of this review was community pharmacists. However, it is necessary to understand what happened in hospitals to fully understand the situation relating to community pharmacists.

Information sources and search strategy

Two investigators (D.K. and T.M.) independently searched for eligible studies published in PubMed, and the Cochrane Library from 1 December 2019 to 31 January 2022. We used the following key words: “novel coronavirus” OR “new coronavirus” OR “emerging coronavirus” OR “2019-nCoV” OR “COVID-19” OR “SARS-CoV-2” AND “pharmacist” OR “chemist” OR “apothecary” OR “pharmaceutist” OR “druggist”. We also reviewed the reference lists of eligible studies using Google Scholar and performed a manual search to ensure that all appropriate studies were included.

Data extraction

Two investigators (D.K. and T.M.) independently searched for eligible studies. Articles obtained from the search were stored in Citation Manager (EndNote 20; Thomson Reuters, New York, NY, USA). After removing redundant articles, we examined the titles, abstracts, and full-text articles. Then, we extracted the data for country, methodology, study design, study participants, study site, sample size, study period, and main focus of each study. Outcome variables were extracted into pre-designed data collection forms. Data accuracy was verified by comparing the collection forms of each investigator, any discrepancies were determined through discussion [25].

Level of evidence

The level of evidence was determined based on the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) framework, which classifies the level of evidence for each outcome based on the risk of bias, imprecision, inconsistency, indirectness, and publication bias [26]. The authors classified the evidence level for each eligible study according to the revised grading system for recommendation in the evidence base guideline (see Additional file 2) [27].

Data analysis

Throughout the meta-analysis, we calculated the prevalence of each outcome variable with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using a random-effects model (generic inverse variance method). To assess the prevalence of the outcome variables among pharmacy practices, the standard error was calculated using the Agresti–Coull method [28]. Heterogeneity among the original studies was evaluated using the I2 statistic [29]. Publication bias was examined using a funnel plot. For all analyses, significance levels were two-tailed, and p < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical tests were performed using Review Manager (RevMan) Version 5.4.1 (Cochrane Collaboration, Copenhagen, Denmark) [30].

Results

Study selection and characteristics

The initial database search identified 497 candidate publications. Of these, 30 studies [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, 15,16,17,18,19, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] reported the outcome variables that met eligibility criteria (Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the included studies.

Of the 30 studies, 27 were cross-sectional studies [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, 15, 17, 18, 31,32,33, 35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44] and 3 were retrospective observational studies based on electronic health records [16, 19, 34]. Although most survey participants in the cross-sectional studies were pharmacists, several studies included customers or patients using community pharmacies [17, 43], home treatment patients [42], and community residents [5] whose responses also indicated pharmacy practices regarding COVID-19. In this study, the largest number of studies on pharmacists’ practices regarding COVID-19 came from the West Asian region with 9 studies [7, 11, 17, 32, 39,40,41,42, 44], the most common country of origin for studies was Jordan [17, 32, 39, 40].

Evaluation of pharmacy practice activities for COVID-19

Table 2 presents the major outcomes of studies of pharmacist practices regarding COVID-19.

Various public health activities were commonly carried out, although the activities reported by pharmacists differed. These outcome variables were integrated into similar categories to estimate the percentage of pharmacist practice activities.

Thirty studies had data on any of the items that met the eligibility criteria [3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, 15,16,17,18,19, 31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. Among the 30 studies with data on the primary outcome, we used meta-analysis to estimate the proportion of pharmacy operations related to COVID-19 in the categories of drugs and information delivery, client education, cleaning and disinfecting regularly, and structural ingenuity for each item.

The estimated proportion of pharmacists who provided telemedicine and home delivery services, classified as drugs and information delivery, were 49.03 and 41.98% respectively (Fig. 2); those who reported providing education for clients regarding COVID-19 was 72.54% (Fig. 3). In the hygiene behaviors item, the estimated proportions of pharmacists who cleaned and disinfected regularly and kept social distance with staff and clients was 81.89 and 76.37%, respectively (Fig. 4). In the structural ingenuity item, 63.88 and 51.00% of the respondents implemented restricted entrance to the pharmacy and restricted access area in the pharmacy, respectively (Fig. 5).

Secondary outcomes

Table 2 presents the various outcomes reported in each study. Of the 30 studies showing pharmacy practice for COVID-19, most focused on community pharmacists; four studies reported on only hospital and clinical pharmacists [15, 16, 19, 34].

Pharmacy practices other than the primary outcome included one report in which “clinical pharmacists recommended medication” for COVID-19 patients admitted to the ICU [34], as well as a report in which community pharmacists limited the number of items per client purchase to eliminate shortages of dietary supplements and medications [37].

Discussion

The present study quantified the extent to which pharmacists are engaged in various public health activities for COVID-19 that augment health and infection prevention strategies for local residents. The most common practice activity of pharmacists in the response to COVID-19 was providing education for community residents.

COVID-19 is an emerging infectious disease with various factors, including prevention and treatment, that are evolving or were unknown, especially in the early days of the pandemic. People needed reliable information relating to COVID-19 and sought out healthcare professionals to provide them the appropriate and necessary information. In fact, in our previous study conducted in the first phases of the pandemic, community pharmacists received more questions from clients regarding COVID-19 than questions regarding drugs and medications [3]. Pharmacists are trusted community health care providers and are not only required to provide consultations as drug experts, but also to provide the necessary information to community residents in an easy-to-understand manner [45]. A scoping review of the role of pharmacists during the COVID-19 pandemic likewise reported that the pharmacist’s primary role was to provide information and counseling to patients [20]. Especially in an emergency situation in the setting of an emerging infectious disease pandemic, pharmacists must adjust their role to place greater emphasis on providing necessary information, conducting consultations and educating local residents. In addition, to augment the information publicly accessible via the media or the internet [3, 9, 36, 39], pharmacists have greater access to reliable scientific information from international organizations such as the World Health Organization and scientific and medical evidence than do the public they serve [4, 11, 32, 35, 41]. This education is the most effective and crucial way to provide information to local residents. In fact, the educational programs conducted by pharmacists for older adults can focus on both the drug regimens for management of their chronic diseases as well as simultaneously on precautions for the personal hygiene management and the necessity of securing physical distance to assist in the prevention of COVID-19 [5, 7, 8, 10, 12, 32, 41]. Some pharmacists’ practice activities adapted to include creating brochures and effectively using visual posters to educate clients about COVID-19 [8, 33, 35]. The results of the present study showing the high frequency of pharmacists providing education to local residents may result from their high level of understanding and motivation of this aspect as a major part of their professional role.

To impede the spread of the COVID-19 epidemic and to curb the impact of many unreliable or intentionally misleading news stories, community pharmacies in Italy worked with the Italian Ministry of Health and others to provide information to the local population on public health responses [13]. This “fake news” not only spreads inaccurate knowledge but has also been reported to have negative health effects on people, including various psychological disorders and fatigue [46]. In many countries, the role of pharmacists has shifted from targeting a product base to providing a variety of nonprescription services for patients [45], and new pharmacist services must continue to expand to reflect new social demands as well as historical changes. As trusted health care providers in the community, pharmacists must provide scientific messages in an easy-to-understand manner and contribute to the education and consultation of community residents regarding infectious diseases. A national survey in Japan reported that community residents consulted community pharmacies more about COVID-19 than medicines [3]. A cross-sectional study among Italian community pharmacy clients confirmed that overall satisfaction with pharmacies is high and that the role of community pharmacies is highly valued [47]. In many countries, community pharmacies are the first point of contact with the health care system for people with health-related problems or who simply need information or reliable evidence-based advice. This is essential even in a crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic [48,49,50].

In the present study, the pharmacist practice reported at the highest frequency was regular cleaning and disinfection activities, followed by keeping social distance from staff and customers. Previous studies indicated that pharmacists, as medical professionals, have basic knowledge about COVID-19 infection control [31, 32, 38]. However, in the present study, the proportion of pharmacists providing home delivery service of medicines was low, even though pharmacist are well informed about the effectiveness of these services in preventing infection. Implementing a home delivery service necessitates additional requirements for the pharmacy, including human resources and distribution expenses. The low proportion of pharmacies offering this service in the pandemic may reflect these difficulties in implementation. Telemedicine is an effective means of offering consultations, especially during the conditions of infectious disease outbreaks. However, telemedicine may also be limited by institutional conditions as well as national infrastructure conditions. Among the studies that reported the adoption of telemedicine, high proportions of implementation were observed only by studies in the United States and Spain [15, 16], with few in low- and middle-income countries [10, 17,18,19].

The present study has some limitations, including those inherent to the nature of systematic reviews and meta-analyses. First, most of the papers included in this study were cross-sectional studies and did not necessarily have a high level of evidence. Because the reported outcomes varied among the studies, the number of studies focusing on each practice varied in this meta-analysis. Second, for the purposes of this analysis it was necessary to clearly organize the activities and focus the wide range of pharmacists’ community activities on the main action items. The categories of community practice activities for COVID-19 were therefore limited to only the items shown in the target criteria, we selected all reported outcome variables from the extracted papers and selected outcomes variables for the present study. Unreported pharmacy practices may exist in each study due to the survey’s focus on defined outcome variables. Third, the published articles included in the study were from only a few countries and did not broadly report practices in many countries. In addition, because the individual observational studies were conducted at different times of the year, we were unable to observe differences in pharmacy practice activities by infection status. Despite these restrictions, the present study is a meta-analysis of pharmacists’ practical activities related to COVID-19, showing the potential of pharmacists and providing important insights for expanding the role of pharmacists in the future.

Some countries have allowed pharmacists to expand their duties to include practices outside the scope of this study, such as COVID-19 vaccination and prescribing oral therapeutics [51,52,53]. However, this is not the case everywhere. We therefore focused on COVID-19-related activities that can be carried out regardless of national systems and backgrounds, and particularly provision of education and consultation by pharmacists. In addition to being involved in regular medication guidance, this work takes advantage of the convenience of pharmacies, where community residents can easily consult with pharmacists, providing rapid access to advice.

Conclusions

In response to the conditions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, pharmacists adapted their practices to engage in various public health activities that have contributed to promoting health and preventing infection for their community residents. The education of local residents is the key element emphasizing the strength of their professional role in the response to COVID-19. Pharmacists have the potential to provide easy-to-understand scientific messages related to infectious diseases, and therefore contribute to protecting the health of local residents.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are included within the paper and the Supporting Information file.

References

World Health Organization. Weekly epidemiological update on COVID-19 - 6 July 2022. [cited 2022 July 12]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19---6-july-2022

Ung COL. Community pharmacist in public health emergencies: quick to action against the coronavirus 2019-nCoV outbreak. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2020;16(4):583–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.02.003.

Kambayashi D, Manabe T, Kawade Y, Hirohara M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practices regarding COVID-19 among pharmacists partnering with community residents: a national survey in Japan. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258805. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0258805.

Hoti K, Jakupi A, Hetemi D, Raka D, Hughes J, Desselle S. Provision of community pharmacy services during COVID-19 pandemic: a cross sectional study of community pharmacists' experiences with preventative measures and sources of information. Int J Clin Pharm. 2020;42(4):1197–206. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01078-1.

Bahlol M, Dewey RS. Pandemic preparedness of community pharmacies for COVID-19. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1888–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.05.009.

Sum ZZ, Ow CJW. Community pharmacy response to infection control during COVID-19. A cross-sectional survey. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1845–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.06.014.

ElGeed H, Owusu Y, Abdulrhim S, Awaisu A, Kattezhathu VS, Abdulrouf PV, et al. Evidence of community pharmacists' response preparedness during COVID-19 public health crisis: a cross-sectional study. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2021;15(1):40–50. https://doi.org/10.3855/jidc.13847.

Elsayed AA, Darwish SF, Zewail MB, Mohammed M, Saeed H, Rabea H. Antibiotic misuse and compliance with infection control measures during COVID-19 pandemic in community pharmacies in Egypt. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(6):e14081. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14081 Epub 2021 Feb 15. Erratum in: Int J Clin Pract. 2021 Dec;75(12):e15016. PMID: 33559255.

Kassem AB, Ghoneim AI, Nounou MI, El-Bassiouny NA. Community pharmacists' needs, education, and readiness in facing COVID-19: actions & recommendations in Egypt. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(11):e14762. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14762.

Novak H, Tadić I, Falamić S, Ortner HM. Pharmacists' role, work practices, and safety measures against COVID-19: a comparative study. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2021;61(4):398–407. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.03.006.

Yılmaz ZK, Şencan N. An examination of the factors affecting community Pharmacists' knowledge, attitudes, and impressions about the COVID-19 pandemic. Turk J Pharm Sci. 2021;18(5):530–40. https://doi.org/10.4274/tjps.galenos.2020.01212.

Giua C, Paoletti G, Minerba L, Malipiero G, Melone G, Heffler E, et al. Community pharmacist's professional adaptation amid Covid-19 emergency: a national survey on Italian pharmacists. Int J Clin Pharm. 2021;43(3):708–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-020-01228-5.

Baratta F, Visentin GM, Ravetto Enri L, Parente M, Pignata I, Venuti F, et al. Community pharmacy practice in Italy during the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic: regulatory changes and a cross-sectional analysis of Seroprevalence. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(5):2302. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18052302.

Cadogan CA, Hughes CM. On the frontline against COVID-19: community pharmacists' contribution during a public health crisis. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):2032–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.015.

Tortajada-Goitia B, Morillo-Verdugo R, Margusino-Framiñán L, Marcos JA, Fernández-Llamazares CM. Survey on the situation of telepharmacy as applied to the outpatient care in hospital pharmacy departments in Spain during the COVID-19 pandemic. Farm Hosp. 2020;44(4):135–40. English. https://doi.org/10.7399/fh.11527.

Yerram P, Thackray J, Modelevsky LR, Land JD, Reiss SN, Spatz KH, et al. Outpatient clinical pharmacy practice in the face of COVID-19 at a cancer center in New York City. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2021;27(2):389–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078155220987625.

Akour A, Elayeh E, Tubeileh R, Hammad A, Ya'Acoub R, Al-Tammemi AB. Role of community pharmacists in medication management during COVID-19 lockdown. Pathog Glob Health. 2021;115(3):168–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/20477724.2021.1884806.

Kua KP, Lee SWH. The coping strategies of community pharmacists and pharmaceutical services provided during COVID-19 in Malaysia. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(12):e14992. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14992.

Wang D, Liu Y, Zeng F, Shi C, Cheng F, Han Y, et al. Evaluation of the role and usefulness of clinical pharmacists at the Fangcang hospital during COVID-19 outbreak. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(8):e14271. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14271.

Visacri MB, Figueiredo IV, Lima TM. Role of pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1799–806. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.07.003.

Pantasri T. Expanded roles of community pharmacists in COVID-19: a scoping literature review. J Am Pharm Assoc. 2022;62(3):649–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.12.013.

Unni EJ, Patel K, Beazer IR, et al. Telepharmacy during COVID-19: a scoping review. Pharmacy (Basel). 2021;9(4):183. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy9040183.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;21(339):b2700. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.b2700.

Stroup DF, Berlin JA, Morton SC, Olkin I, Williamson GD, Rennie D, et al. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology: a proposal for reporting. Meta-analysis of observational studies in epidemiology (MOOSE) group. JAMA. 2000;283(15):2008–12. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.283.15.2008.

Manabe T, Kambayashi D, Akatsu H, et al. Favipiravir for the treatment of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21(1):489. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-021-06164-x.

Balshem H, Helfand M, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, et al. GRADE guidelines: 3. Rating the quality of evidence. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(4):401–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.07.015.

Harbour R, Miller J. A new system for grading recommendations in evidence based guidelines. BMJ. 2001;323(7308):334–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.323.7308.334.

Agresti A, Coull BA. Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am Stat. 1998;52:119–26.

Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557.

Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.4.1, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2020. [cited 2022 January 1]. Available from: https://training.cochrane.org/online-learning/core-software-cochrane-reviews/revman/revman-5-download

Hussain I, Majeed A, Saeed H, Hashmi FK, Imran I, Akbar M, et al. A national study to assess pharmacists' preparedness against COVID-19 during its rapid rise period in Pakistan. PLoS One. 2020;15(11):e0241467. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0241467.

Abdel Jalil M, Alsous MM, Abu Hammour K, Saleh MM, Mousa R, Hammad EA. Role of pharmacists in COVID-19 disease: a Jordanian perspective. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2020;14(6):782–8. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.186.

Meghana A, Aparna Y, Chandra SM, Sanjeev S. Emergency preparedness and response (EP&R) by pharmacy professionals in India: lessons from the COVID-19 pandemic and the way forward. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):2018–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.028.

Wang R, Kong L, Xu Q, Yang P, Wang X, Chen N, et al. On-ward participation of clinical pharmacists in a Chinese intensive care unit for patients with COVID-19: a retrospective, observational study. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1853–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.06.005.

Zaidi STR, Hasan SS. Personal protective practices and pharmacy services delivery by community pharmacists during COVID-19 pandemic: results from a national survey. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1832–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.07.006.

Muhammad K, Saqlain M, Muhammad G, Hamdard A, Naveed M, Butt MH, et al. Y. Knowledge, attitude, and practices (KAPs) of community pharmacists regarding COVID-19: a cross-sectional survey in 2 provinces of Pakistan. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2021;16:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2021.54.

Jovičić-Bata J, Pavlović N, Milošević N, Gavarić N, Goločorbin-Kon S, Todorović N, et al. Coping with the burden of the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study of community pharmacists from Serbia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2021;21(1):304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06327-1.

Nguyen HTT, Dinh DX, Nguyen VM. Knowledge, attitude and practices of community pharmacists regarding COVID-19: a paper-based survey in Vietnam. PLoS One. 2021;16(7):e0255420. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0255420.

Al-Daghastani T, Tadros O, Arabiyat S, Jaber D, AlSalamat H. Pharmacists' perception of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) in Jordan: a cross-sectional study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111541.

Elayeh E, Akour A, Haddadin RN. Prevalence and predictors of self-medication drugs to prevent or treat COVID-19: experience from a middle eastern country. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(11):e14860. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14860.

Okuyan B, Bektay MY, Kingir ZB, Save D, Sancar M. Community pharmacy cognitive services during the COVID-19 pandemic: a descriptive study of practices, precautions taken, perceived enablers and barriers and burnout. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(12):e14834. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14834.

Mukattash TL, Jarab AS, Al-Qerem W, Abu Farha RK, Itani R, Karout S, et al. Coronavirus disease patients' views and experiences of pharmaceutical care services in Lebanon. Int J Pharm Pract. 2022;30(1):82–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpp/riab071.

Patel J, Christofferson N, Goodlet KJ. Pharmacist-provided SARS-CoV-2 testing targeting a majority-Hispanic community during the early COVID-19 pandemic: Results of a patient perception survey. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2022;62(1):187–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.08.015.

Alnajjar MS, ZainAlAbdin S, Arafat M, Skaik S, AbuRuz S. Pharmacists’ knowledge, attitude and practice in the UAE toward the public health crisis of COVID-19: A cross-sectional study. Pharm Pract (Granada). 2022;20(1):2628. https://doi.org/10.18549/PharmPract.2022.1.2628.

Bragazzi NL, Mansour M, Bonsignore A, Ciliberti R. The role of hospital and community pharmacists in the management of COVID-19: towards an expanded definition of the roles, responsibilities, and duties of the pharmacist. Pharmacy (Basel). 2020;8(3):140. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy8030140.

Rocha YM, de Moura GA, Desidério GA, de Oliveira CH, Lourenço FD, de Figueiredo Nicolete LD. The impact of fake news on social media and its influence on health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. Z Gesundh Wiss. 2021;9:1–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01658-z.

Baratta F, Ciccolella M, Brusa P. The relationship between customers and community pharmacies during the COVID-19 (SARS-CoV-2) pandemic: a survey from Italy. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(18):9582. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18189582.

Al-Quteimat OM, Amer AM. SARS-CoV-2 outbreak: how can pharmacists help? Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(2):480–2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.03.018.

Hedima EW, Adeyemi MS, Ikunaiye NY. Community pharmacists: on the frontline of health service against COVID-19 in LMICs. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2021;17(1):1964–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sapharm.2020.04.013.

International Pharmaceutical Federation. FIP COVID-19 guidance (Part 2): Guidelines for pharmacists and the pharmacy workforce. [cited 2023 January 4]. Available from: https://www.fip.org/file/4729

American Pharmacists Association. Pharmacists' Guide To Coronavirus. [cited 2023 January 4]. Available from: https://www.pharmacist.com/coronavirus

Canadian Pharmacists Association. Professional Practice & Advocacy, COVID-19. [cited 2023 January 4]. Available from: https://www.pharmacists.ca/advocacy/issues/covid-19-information-for-pharmacists/

Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. COVID-19 information for pharmacists. [cited 2023 January 4]. Available from: https://www.psa.org.au/coronavirus/

Acknowledgements

We thank John Daniel for editing the English text of a draft of this manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by a grant from Japan Science and Technology (JST), JST-Mirai Program (#20345310). The funders had no role in the design, methods, participant recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: DK and TM. Performed the experiments: DK, TM, MH. Analysed the data: DK. Interpreted the study results: DK, TM, MH. Supervision: MH. Wrote the first draft of the manuscript: DK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The institutional review board and patient consent were not required because of the review nature of this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

PRISMA checklist.

Additional file 2:

Classification standard of the evidence level.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Kambayashi, D., Manabe, T. & Hirohara, M. Adaptations in the role of pharmacists under the conditions of the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Health Serv Res 23, 72 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09071-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09071-w