Abstract

Background

Current research demonstrates that health information technology can improve the efficiency and quality of health services. However, many implementation projects have failed due to behavioural problems associated with technology usages, such as underuse, resistance, sabotage, and even rejection by potential users. Therefore, user acceptance was one of the main factors contributing to the success of health information technology implementation. However, research suggests that behavioural models do not universally hold across cultures.

The present article considers national cultural values (power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, and time orientation) as individual difference variables that affect user behaviour and incorporates them into the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) as moderators of technology acceptance relationships. Therefore, this research analyses which national cultural values affect technology acceptance behaviour in hospitals.

Methods

The authors develop and test seven hypotheses regarding this relationship using the partial least squares (PLS) technique, a structural equation modelling method. The authors collected data from 160 questionnaires completed by clinicians and non-clinicians working in one hospital.

Results

The findings show that uncertainty avoidance, masculinity/femininity, and time orientation are the national cultural values that affect technology acceptance in hospitals. In particular, individuals with masculine cultural values, higher uncertainty avoidance, and a long-term orientation influence behavioural intention to use technology.

Conclusion

The bureaucratic model still decisively characterises the Italian health sector and consequently affects the choices of firms and workers, including the choice of technology adoption. Cultural values of masculinity, risk aversion, and long-term orientation affect intention to use through social norms rather than through perceived utility.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Current research demonstrates that health information technology (HIT) can improve patient safety and healthcare quality, yielding cost savings and reducing medical error rates [1]. However, many implementation projects within the health sector have failed or been abandoned [2]. One of the major factors leading to failure is the inadequate understanding of how clinicians and users react to implemented HIT [3]. For example, Bhattacherjee and Hikmet [4] investigated behavioural problems associated with HIT usage, such as physician resistance, showing that there has been little research on why or how behavioural problems occur. Therefore, several barriers must be overcome for HIT implementation in a hospital [5,6,7].

Technologies usage in medical settings frequently collides with users’ resistance, even if they can benefit from their use [4]. HIT implementation can be linked to underuse, resistance, and sabotage by users, which means many difficulties to achieve the innovation potential imbued in the technology [8]. Therefore, the research considers user acceptance as an important factor contributing to HIT success. In line with this, the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM) [9, 10] is the framework most frequently used to explain users’ acceptance behaviour towards technology. According to the TAM, the behavioural intention to use technology is determined by two beliefs ([10], p. 320): the perceived usefulness (PU), “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would enhance his or her job performance”; and the perceived ease of use (PEOU), “the degree to which a person believes that using a particular system would be free of effort”. Several studies have aimed to improve the TAM model, such as the inclusion of subjective norms (SNs), “the person’s perception that most people who are important to him think he should or should not perform the behaviour in question” ([11], p. 302).

Melas et al. [12] highlighted that the TAM is a good predictor of HIT acceptance. In particular, the reviews by Yarbrough and Smith [13] and Holden and Karsh [3] on the utilisation of the TAM in the healthcare context shown that studies are heterogeneous and attach little importance to moderators, despite TAM research’s findings [12]. In addition, research suggests that behavioural models tend to differ across cultures [15,16,17]. Thus, Lin [14] explored national cultural differences as moderators of nurses’ perspectives on HIT acceptance. Therefore, a research stream emphasises national cultural values as individual difference variables that can play a moderating role within TAM relationships [18, 19, 14].

The current study is part of this research stream and analyses how national culture impacts technology acceptance in healthcare.

Hofstede defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind which distinguishes the members of one human group from another” [15]. To date, the most popular conceptualisation of national culture has been Hofstede’s [15, 20] taxonomy and subsequent extensions [21], describing culture along the following dimensions: power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism-collectivism, masculinity-femininity, and time orientation. According to Hofstede [20] and Hofstede and Bond [21], the cultural dimensions are the following:

-

1)

power distance refers to how people accept the relationship of hierarchical power, that is, the degree of inequality that exists within society;

-

2)

uncertainty avoidance is the degree to which a society is averse to uncertainty and ambiguity;

-

3)

individualism-collectivism represents a preference for a society that emphasises individual goals (individualism), while collectivism is a society where people are integrated into groups;

-

4)

masculinity-femininity refers to the preference for ambition or material success, that is, a society that stresses different gender roles (high masculinity) vs low preference (femininity);

-

5)

time orientation is the degree to which people emphasise future benefit (long-term orientation) or stress immediate rewards (short-term orientation).

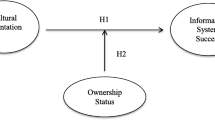

Hence, this study considers national cultural values (power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, and time orientation) as individual difference variables that affect user behaviour and incorporates them into the TAM as moderators of technology acceptance relationships. Therefore, the research question of this article is as follows: which national cultural values promote users’ acceptance of technology in hospitals?

Research model

Research has shown that masculine or feminine values affect relationships in the TAM [18, 22, 23, 14]. Thus, some scholars [18, 23] have stressed that differences in the perception and use of technology might be affected by psychological gender, the prevalence of masculinity or femininity values within society [24, 25]. A working environment with high masculinity is generally characterised by values such as competitiveness and material success, and people tend to be goal-oriented; research has shown that such values can be linked to the individual perceived that technology might improve job performance (perceived usefulness) [26, 27, 18, 14]. Therefore, individuals who espouse masculine cultural values tend to give more emphasis on perceived usefulness than individuals who espouse feminine cultural values.

Moreover, Srite and Karahanna [18] observed that individuals who espouse feminine cultural values are most interested in the quality of work-life and the creation of pleasant and less frustrating work values [25]. These people are inclined to adopt technology that requires little or no effort and, thus, they tend to emphasise perceived ease of use, that is, on the extent to which using the technology is effort-free and easy to use [28]. Hence, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The espoused national cultural value of masculinity/femininity moderates the relationship between perceived usefulness and behavioural intention as well as the relationship between perceived ease of use and behavioural intention.

Masculinity-femininity can also influence the relationship between social norms and behavioural intention to use [26]. According to Bollinger and Hofstede [29], a masculine culture is characterised by competition and success; thus, societies with higher masculinity levels stand out by a desire for material goods and the importance of social status. Bollinger and Hofstede [29] consider Italy a society with a masculine culture since Italian people attach importance to a search for competitive results, affecting technology use behaviour [18, 14]. In highly bureaucratised environments, such as hospitals, the prevailing social behaviour conforms to the majority without undertaking innovative paths [30]. Wooten and Crane [31] observed that clan control mechanisms are developed (congruence of objectives and shared values) to coordinate the individual’s behaviour; consequently, in hospitals, the clan mechanism facilitates the generation of consensus decision making. The bureaucratised environment and the goal orientation of physicians’ work can make the hospital management or peer pressure influence whether a physician will adopt a technology [19]. Thus, pressure in the pursuit of success leads people to consider the social influence of supervisors or peers. Some studies have investigated the cultural value of individualism/collectivism within the relationship between subjective norms and behavioural intention to use [32, 18, 33,34,35]. In collectivist cultures, people are significantly influenced by the group and take into account of opinions of others, mainly to satisfy the need for approval from the group [24]. In contrast, individuals who espouse individualistic cultural values tend to be self-oriented, believe in individual decisions, and are more independent and less loyal to the group than people from collectivistic cultures [27]. Therefore, in a high-individualism cultural environment, people are less concerned with the opinions of others [18]. Thus, the influence of subjective norms on behavioural intention is stronger in a collectivistic culture [32]. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The relationship between subjective norms and behavioural intention to use is moderated by the espoused national cultural values of masculinity/femininity and of individualism/collectivism such that the relationship is stronger for individuals with espoused masculine and collectivistic cultural values.

Scholars have suggested that the cultural value of power distance might moderate the relationship between subjective norms and behavioural intention to use [36, 18, 37,38,39]. People with higher power distance levels tend to be more careful in conforming to the opinions of their superiors [40, 19]. Therefore, these individuals would be more influenced by social norms when deciding whether to adopt technologies [18, 39].

Furthermore, individuals with high uncertainty avoidance values tend to respect rules and adapt to others’ opinions, supervisors, and peers, to reduce this uncertainty [18, 40, 19]. In this context, subjective norms may reduce uncertainty when peers, supervisors, or friends share personal experiences and perceptions of the technology [18]. Thus, social norms might serve as determinants of behaviour for individuals with higher uncertainty avoidance values than those with uncertainty avoidance values. Thus, the research hypothesizes as follows:

Hypothesis 3: The relationship between subjective norms and behavioural intention to use is moderated by the espoused national cultural values of power distance and of uncertainty avoidance such that the relationship is stronger for individuals with higher espoused power distance and uncertainty avoidance cultural values.

Time orientation (short- vs long-term orientation) may affect users’ perception of technology and, particularly, their behavioural intention to use technology [41,42,43, 14, 28]. Cultures with a long-term orientation tend to foster trust and behaviours such as thrift or perseverance towards future rewards; in contrast, cultures with a short-term orientation tend to exhibit a focus on achieving quick results [43].

People with long-term orientation tend to be bonded to current working practices and the routine and values intrinsic in their specific tasks [15]. Indeed, Hofstede [15] highlighted that adaptiveness is the principal work value of long-term orientation. A level low on this dimension, for example, indicates the preference to preserve traditions and norms consolidated over time. Instead, a level high on long-term orientation indicates a more practical approach and, thus, the capacity to adapt traditions with ease to changing conditions. Some scholars have shown that cultures with high long-term orientation levels are more likely to adopt new technologies [44]. Moreover, long-term orientation also increases the imitation effect [45]: traditions can be an obstacle to change, but, one time a change is socially accepted, it is rapidly implemented. Thus, the long-term orientation would more affect intention to use technology than short-term orientation for individuals.

Hypothesis 4: Individuals who are long-term oriented will exert more of an influence on behavioural intention to use technology.

The research model is shown in Fig. 1.

Methodology

The proposed model was tested through a quantitative methodology. A survey method for data collection was used to gather data from September to December 2019. Data were collected by administering a structured questionnaire in the Italian language to 400 healthcare workers (clinicians and non-clinicians) in one of the largest hospitals in southern Italy. A pilot test was conducted with three healthcare managers to assess the consistency of translated items.

Of the 300 administered questionnaires, 190 were returned completed (response rate of 63%). All the collected data were checked for consistency to minimise data entry errors. As a result, 160 valid responses were included.

The questionnaire was divided into two sections. The first section was intended to capture the profile of the survey respondents (age, gender, education level, and IT experience), while the second section contained 32 survey questions derived from the existing IS literature. In particular, BI and SN were measured using Venkatesh and Davis’s [46] two-item scale, while PU and PEOU were measured using Venkatesh and Davis’s [46] four-item scale. Finally, cultural orientation variables, such as MF, IC, PD, UC, and LT, were measured using Baptista and Oliveira’s [47] twenty-item scale. All variables were measured on a seven-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ [1] to ‘strongly agree’ [7].

Data analysis and results

The data analysis was performed using the partial least squares (PLS) method, a structural equation modelling technique used in IS research [48]. Consistent with prior IS research [49], data was perfomed through a PLS-SEM application (XLSTAT) by using a reflective measurement model (i.e., indicators of a construct are considered to be caused by that construct). Using XLSTAT, we first established the psychometric validity of the scales used through the construct reliability -Cronbach’s alpha (α) and composite reliability (ρc)- and discriminant validity -Average Variance Extracted (AVE)-.

Regarding the construct reliability, we noted that both α and ρc must be greater than 0.80 (BI: α = 0.89, ρc = 0.93; PEOU: α = 0.92, ρc = 0.94; PU: α = 0.91, ρc = 0.94; SN: α = 0.90, ρc = 0.92; MF: α = 0.97, ρc = 0.98; IC: α = 0.87, ρc = 0.91; PD: α = 0.88, ρc = 0.92; UC: α = 0.89, ρc = 0.92; and LT: α = 0.92, ρc = 0.94) to indicate good reliability.

Regarding the discriminant validity, we noted that the square root of the AVE for each construct (diagonal of Table 1) is larger than the correlations with other constructs. Table 1 shows the comparison between the AVE and construct correlations.

Moreover, we also noted that all items have factor loadings of 0.70 or greater on their corresponding constructs, as well as they load to a low extent on the other ones, so confirming the discriminant validity. The Additional file 1 displays the scales used in the study and the related factor loadings.

After verifying the constructs’ reliability and the discriminant validity, data analysis was performed using the PLS technique. Table 2 shows the findings of the PLS analysis.

Table 2 shows the findings of the PLS analysis. The three models reported in Table 2 (I, II, and III) show the effects of the independent and moderator variables on dependent variables (PU and BI). In particular, Table 2 shows the effects of the PEOU independent variable on the PU dependent variable (Model I), the effects of the TAM variables and SN on the BI dependent variable (Model II), and the effects of the independent (PEOU, PU, SN, and LT) and moderating variables (MF, IC, PD, and UC) on the BI dependent variable (Model III).

As shown in Table 2, the proposed research model explains approximately 76% of the variance, which SN (β = 0.560, p ≤ 0.005) and LT (β = 0.181, p ≤ 0.005) significantly determine BI independent variables. Thus, hypothesis H4 is supported by the data.

Unlike, findings show that PU and PEOU do not affect BI, thus H1 isn’t supported by the data. Furthermore, the findings of the PLS analysis also show that MF (β = 1.212 m p ≤ 0.010), IC (β = -2.203 m p ≤ 0.005), and UC (β = 2.358, p ≤ 0.005) moderate the relationship between SN and BI, while PD doesn’t moderate this relationship. However, unlike we hypothesised, the explanatory contribution of IC is negative; thus, H2 and H3 are only partially supported by the data.

Discussion

The study analysed how national cultural values (power distance, uncertainty avoidance, individualism/collectivism, masculinity/femininity, and time orientation) affect technology acceptance in hospitals.

In order to test how national cultural values affect the technology acceptance model, we first tested the explanatory contributions of the leading technology model variables revealed by the IS literature, such as PU, PEOU, and SN, to BI. Our findings have shown that PU and PEOU do not affect BI. Empirical investigations on technology acceptance model testing have shown that PEOU does not always influence BI, while the explanatory contribution of PU to BI is often found. In our study, PU does not affect BI simply because using new information technology is mandatory and therefore not linked to its characteristics and usefulness. In other words, in Italian public health, the active involvement of those who will have to use new technologies in the innovation process is not envisaged as they are required to comply with the law and not choose to improve their performance [50]. This pattern is typical of bureaucracy [7]. In particular, in the context of Italian public hospitals, the strong and rooted bureaucratic culture amplifies the effect of national cultural values on the methods of using new technologies. In this regard, several studies [51,52,53] highlighted the relationships between national culture and bureaucratic culture, highlighting precisely how there is a possible overlap and emphasis between them. In other words, bureaucracy can be understood as a real manifestation of the cultural model prevalent in a specific nation, a sort of output which, at the same time, also acts as a driver or input to strengthen and consolidate the same clutural values.

In general, bureaucracy is characterised by adherence to written laws, depersonalisation of working relationships, command line hierarchy, and the separation of actions and consequences [54]. In reality, bureaucracy manifests itself in Italy than in other countries by ignoring the connection between individual action and the outcome, both individually and collectively [55]. Furthermore, the bureaucratic rationale is compounded since the healthcare sector is a professional bureaucracy linked to the special abilities held by some categories, such as physicians, nurses, and others. Organisations in this sector, such as hospitals, operate as a clan, a closed structure, which impedes creativity and change. As a consequence, the bureaucratic context is strengthened, forming a vicious cycle [31].

Furthermore, our findings have also shown that SN positively affects BI. This result is consistent with the existing TAM literature [18]. As noted above, the bureaucratic context of Italian healthcare is characterised by processes of isomorphism, which discourage innovation or the adoption of new tools in the single hospital, especially because innovation processes are guided by a top-down orientation, where hospitals also suffer from an almost centralised purchasing process, which severely limits their autonomy. The working climate, in this scenario, influences the BI and the behaviour of use in the conformist direction [56].

Furthermore, since the 1990s, when the healthcare system was reforming according to new public management, the emphasis has been solely on efficiency and productivity, resulting in the standardisation of individual operator activity [57]. Furthermore, the later-introduced compensation and incentive systems have mirrored this strategy, flattening individual performance [58].

Regarding the cultural variables, our findings have shown that masculinity/femininity and uncertainty avoidance moderate the relationships between subjective norms and behavioural intention to use.

Masculine/feminine values had a significant moderating effect on the relationship between subjective norms and behavioural intention to use such that this relationship was stronger for masculine cultures. In particular, our findings show that the prevalence of a masculine culture is linked to an incessant search for results from a competitive perspective, and this decisively affects the way technology is used [18, 14]. As already highlighted, in highly bureaucratised environments, the prevailing social behaviour advises not taking innovative paths but conforming to the majority, thus having an external or contextual influence on the behaviour of use [30]. In addition, the clan logic, which is characteristic of masculinity, expresses itself as obedience to the will of those who administer the institution [31].

A mechanism copy logic predominates in the healthcare context and introduces changes and innovation [50]. This is in line with the professional bureaucracy and stems in Italy from the legal approach for reforms [58].

Furthermore, our results have also shown that the individualism/collectivism cultural variable significantly moderates the relationship between SN and BI; however, inconsistent with our hypothesis, the explanatory contribution is negative. Our findings show that the prevalence of individualistic cultural value leads healthcare workers to obtain advantages from aligned solutions, giving up space of autonomy. Therefore, it is not surprising that in the Italian context under investigation, the effect of SN on BI diminishes as a collectivist culture grows. In fact, in the competitive search for results and performance, the collectivist approach is not consistent as it would act as a brake on the choice of different methods of using the technology. In other words, collectivist culture negatively affects BI because it hinders the search for individual performance improvement.

In general, health organisations are confirmed as an individualistic context in which the individual adopts behaviours aimed at optimising personal goals concerning those of the organisation [59]. In particular, this is achieved by adhering to the organisation’s rules and procedures. As confirmed by other studies, the ease of use facilitates the acceptance of new technology; that is, it is the decisive factor in the collectivist approach [14, 42, 60].

Regarding uncertainty avoidance cultural values, risk aversion prevails, which, as seen from the data, increases the effect of social influence on user behaviour. The different actors do not work in dynamic and incentive contexts, so there are no benefits in changing the status quo. In the health sector, in particular, the dominant culture provides risk aversion, i.e., the reduction of uncertainty for achieving a goal [14, 61, 62]. As already highlighted, in Italy, the prevalence of the bureaucratic model induces standardised behaviour [63].

Finally, our findings have shown that long-term orientation positively affects users’ behavioural intention to use technology. The operators are permanent employees of the hospitals and, therefore, will work in the same context for a long time. Furthermore, they know that the choices of adopting a new technology concern the long term and that, as such, they are difficult to change in the short term. For this reason, the sooner they learn to use it and use it, the greater the benefits will be for them; thus, only an orientation towards stability (and, therefore, the long term) can help to favour the spread of new tools. This result is not confirmed in the literature in similar contexts [14, 46] since, in previous studies, the orientation of professionals towards the goal in the short term did not influence the long-term approach.

Research implications, conclusions and limits

This research demonstrates how Hofstede’s cultural model contributes to highlighting variables capable of increasing the success of the TAM, in its original dimension, concerning the intention to use new technology.

Overall, this will help improve the effectiveness of the implementation processes of new technologies, thus reducing waste of time and resources and failures and rejections.

The analysis was conducted in the Italian hospital healthcare context, which showed some peculiarities [64]. In this context, it is possible to find several studies that have applied the different models individually [65,66,67], but there have been few attempts to integrate the two [14].

These considerations have at least two implications: one on the theoretical level and the other on the managerial level.

From the theoretical point of view, if the integration of the Hofstede model with the TAM has helped improve its explanatory capabilities, the need for further integration is also highlighted, i.e., with cultural models that consider the sectorial peculiarities in which the analysis occur. As seen from the results, it is precisely the intrinsic characteristics of the Italian healthcare context that determine the possible explanation of the use methods, albeit mediated by Hofstede’s approach. In other words, in the context of national culture, a decisive role is played, also in this case in an integrated way, by the operational particularities of the sector in which the actors involved in the decisions of use operate [68].

In summary, it can be said that the characteristics of the bureaucratic approach, which still decisively characterises the Italian public administration and the health system, are the key factors in guiding the choices of firms and workers [69, 70].

On closer inspection, however, it is a cultural variable and therefore able to interact well with both the Hofstede model and the TAM, albeit at a different and more operational level. The first reason is that it affects that delicate boundary sphere between the values of the individual and the values of the company in which and for which he works; and the second reason is that the intention of use is, in the examined context, more guided by the social norm, understood in a broad sense, concerning perceived utility.

Future research could consider other variables, such as the OCAI model [71] widely used in the healthcare context [72, 62, 7, 51, 73], and investigate the possible role played by bureaucratic culture as a factor that influence the relations between national cultural values and the use of new technologies. Some of these studies highlighted differences between public hospitals and private hospitals, suggesting, among others, the explanatory role of state ownership as a decisive variable in influencing the success of information systems.

Additionally, from a managerial point of view, the usefulness of the Hofstede model in supporting the implementation of processes for the adoption of new technologies is confirmed. In this sense, the data also suggest, in the health sector, the importance for the legislature and management to consider the cultural characteristics of the context in which innovation is going to be placed before selecting new technologies in order to avoid the first failure and then the abandonment of new technologies, as known in the doctrine.

Furthermore, while not discounting the importance of economic convenience or financial limitations in the introduction of new technology [73, 74], the study demonstrates that management must also recognise the involvement of primarily male or female staff and the various types of wards.

Finally, the management entrusted with implementing the new technology, therefore, should clarify in advance that this is an irreversible choice, at least in the short term, if it wants to make the adoption process more efficient.

Furthermore, this variable is consistent with the highly bureaucratic scenario that has always characterised Italian healthcare and, more generally, state institutions [75, 76]. In this context, cultural values of masculinity, risk aversion, and long-term orientation that the findings show are factors capable of affecting intention of use further suggest that managers observe the field of action in advance using a compatible perspective. For example, technology could be modelled more from the user’s perspective.

There are several limitations of the present work. The analysed sample has a low number of observations, so the results are not generalisable; furthermore, considering only the Italian scenario, reference is made to the prevailing cultural model in that country. It may be interesting to extend this survey in future research, especially to culturally distant national contexts.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HIT:

-

Health information technology

- TAM:

-

Technology Acceptance Model

- PU:

-

Perceived usefulness

- PEOU:

-

Perceived ease of use

- SN:

-

Subjective norm

- PD:

-

Power distance

- UC:

-

Uncertainty avoidance

- IC:

-

Individualism-collectivism

- MF:

-

Masculinity-femininity

- LO:

-

Long-term orientation

References

Shekelle PG, Morton SC, Keeler EB. Costs and benefits of health information technology. Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2006;132(April):1–71.

Kijsanayotin B, Pannarunothai S, Speedie SM. Factors influencing health information technology adoption in Thailand’s community health centers: applying the UTAUT model. Int J Med Informatics. 2009;78(6):404–16.

Holden RJ, Karsh BT. The technology acceptance model: its past and its future in health care. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43(1):159–72.

Bhattacherjee A, Hikmet N. Physicians’ resistance toward healthcare information technology: a theoretical model and empirical test. Eur J Inf Syst. 2007;16(6):725–37.

Paré G, Trudel MC. Knowledge barriers to PACS adoption and implementation in hospitals. Int J Med Informatics. 2007;76(1):22–33.

Pynoo B, Devolder P, Tondeur J, Van Braak J, Duyck W, Duyck P. Predicting secondary school teachers’ acceptance and use of a digital learning environment: a cross-sectional study. Comput Hum Behav. 2011;27(1):568–75.

Lepore L, Metallo C, Schiavone F, Landriani L. Cultural orientations and information systems success in public and private hospitals: preliminary evidence from Italy. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):554.

Lapointe L, Rivard S. A multilevel model of resistance to information technology implementation. MIS quarterly. 2005;29(3):461–91.

Davis FD. Technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: theory and results. Unpublished doc-toral dissertation. Cambridge: MIT Sloan School of Management; 1986.

Davis FD. Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS quarterly. 1989;13(3):319–40.

Fishbein M, Ajzen I. Belief, attitude, intention, and behavior: an introduction to theory and research. Reading Mass: Addison-Wesley; 1975.

Melas CD, Zampetakis LA, Dimopoulou A, Moustakis V. Modeling the acceptance of clinical information systems among hospital medical staff: an extended TAM model. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(4):553–64.

Yarbrough AK, Smith TB. Technology acceptance among physicians: a new take on TAM. Med Care Res Rev. 2007;64(6):650–72.

Lin HC. The impact of national cultural differences on nurses’ acceptance of hospital information systems. Comput Inform Nurs. 2015;33(6):265–72.

Hofstede G. Motivation, leadership, and organisation: do American theories apply abroad? Organ Dyn. 1980;9(1):42–63.

Keil M, Tan BC, Wei KK, Saarinen T, Tuunainen V, Wassenaar A. A cross-cultural study on escalation of commitment behavior in software projects. MIS quarterly. 2000;24(2):299–325.

Straub D, Keil M, Brenner W. Testing the technology acceptance model across cultures: a three country study. Inf Manag. 1997;33(1):1–11.

Srite M, Karahanna E. The role of espoused national cultural values in technology acceptance. MIS quarterly. 2006;30(3):679–704.

Lin HC. An investigation of the effects of cultural differences on physicians’ perceptions of information technology acceptance as they relate to knowledge management systems. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;38:368–80.

Hofstede G. The cultural relativity of organisational practices and theories. J Int Bus Stud. 1983;14(2):75–89.

Hofstede G, Bond MH. The confucius connection: from cultural roots to economic growth. Organ Dyn. 1988;16(4):5–21.

McCoy S, Galletta DF, King WR. Applying TAM across cultures: the need for caution. Eur J Inf Syst. 2007;16(1):81–90.

Cyr D, Gefen D, Walczuch R. Exploring the relative impact of biological sex and masculinity–femininity values on information technology use. Behav Inf Technol. 2017;36(2):178–93.

Bem SL, Role BS, Inventory: Professional manual. Palo Alto. CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1981.

Hofstede G. Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values (Vol. 5). New York, NY: Sage; 1984.

Srite, M. "The Influence of National Culture on the Acceptance and Use of Information Technologies: An Empirical Study" (1999). AMCIS 1999 Proceedings. 355. http://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis1999/355.

Veena Parboteeah D, Praveen Parboteeah K, Cullen JB, Basu C. Perceived usefulness of information technology: a cross-national model. J Glob Inf Technol Manag. 2005;8(4):29–48.

Lin HC, Ho WH. Cultural effects on use of online social media for health-related information acquisition and sharing in Taiwan. Int J of Hum Comput Int. 2018;34(11):1063–76.

Bollinger D, Hofstede G. Les différences culturelles dans le management : comment chaque pays gère-t-il ses hommes ? Paris: Edition d’organisations; 1987.

Davies HT. Understanding organisational culture in reforming the national health service. J R Soc Med. 2002;95(3):140–2.

Wooten LP, Crane P. Generating dynamic capabilities through a humanistic work ideology: the case of a certified-nurse midwife practice in a professional bureaucracy. Am Behav Sci. 2004;47(6):848–66.

Chau PYK, Hu PJH. Information technology acceptance by individual professionals: a model comparison approach. Dec Sci. 2001;32(4):699–719.

Hung CL, Chou JCL, Chung RY, Dong TP. A cross-cultural study on the mobile commerce acceptance model. Management of Innovation and Technology (ICMIT), IEEE international conference; 2010. p. 462–467.

Zhang L, Zhu J, Liu Q. A meta-analysis of mobile commerce adoption and the moderating effect of culture. Comput Hum Behav. 2012;28(5):1902–11.

Faqih KM, Jaradat MIRM. Assessing the moderating effect of gender differences and individualism-collectivism at individual-level on the adoption of mobile commerce technology: TAM3 perspective. J Retail Consum Serv. 2015;22:37–52.

McCoy S, Everard A, Jones BM. An examination of the technology acceptance model in Uruguay and the US: A focus on culture. J Glob Inf Technol Manag. 2005;8(2):27–45.

Dinev T, Goo J, Hu Q, Nam K. User behavior towards protective information technologies: the role of national cultural differences. Inf Syst J. 2009;19(4):391–412.

Li X, Hess TJ, McNab AL, Yu Y. Culture and acceptance of global web sites: a cross-country study of the effects of national cultural values on acceptance of a personal web portal. ACM SIGMIS Database. 2009;40(4):49–74.

Tarhini A, Hone K, Liu X, Tarhini T. Examining the moderating effect of individual-level cultural values on users’ acceptance of e-learning in developing countries: a structural equation modeling of an extended technology acceptance model. Interact Learn Environ. 2017;25(3):306–28.

Sun H, Zhang P. The role of moderating factors in user technology acceptance. Int J Hum Comput Stud. 2006;64(2):53–78.

Chau PY. An empirical assessment of a modified technology acceptance model. J Manag Inf Syst. 1996;13(2):185–204.

Veiga JF, Floyd S, Dechant K. Towards modelling the effects of national culture on IT implementation and acceptance. J Inf Technol. 2001;16(3):145–58.

Yoon C. The effects of national culture values on consumer acceptance of e-commerce: online shoppers in China. Inf Manag. 2009;46(5):294–301.

Özbilen P. The impact of natural culture on new technology adoption by firms: a country level analysis. Int J Innov Manag Technol. 2017;8(4):299–305.

Lee SG, Trimi S, Kim C. The impact of cultural differences on technology adoption. J World Bus. 2013;48(1):20–9.

Venkatesh V, Davis FD. A theoretical extension of the technology acceptance model: four longitudinal field studies. Manage Sci. 2000;46(2):186–204.

Baptista G, Oliveira T. Understanding mobile banking: the unified theory of acceptance and use of technology combined with cultural moderators. Comput Hum Behav. 2015;50:418–30.

Urbach N, Ahlemann F. Structural equation modelling in information systems research using partial least squares. JITTA. 2010;11(2):5–40.

Ringle CM, Sarstedt M, Straub DW. Editor’s comments: a critical look at the use of PLS-SEM in" MIS Quarterly". MIS quarterly. 2012;36:iii–xiv.

Marques IC, Ferreira JJ. Digital transformation in the area of health: systematic review of 45 years of evolution. Heal Technol. 2020;10(3):575–86.

Møller MØ. Street-level bureaucracy research and the specification of national culture. Research handbook on street-level bureaucracy, by Hupe P. Edward Elgar publishing; 2019.

Takle M. Immigrant organisations as schools of bureaucracy. Ethnicities. 2015;15(1):92–111.

Im T, Campbell JW, Cha S. Revisiting Confucian bureaucracy: roots of the Korean government’s culture and competitiveness. Public Admin Dev. 2013;33(4):286–96.

Blaise P, Kegels G. Managing change in bureaucratic health care organisations. A case study of a quality improvement project in Zimbabwe. In Proceedings of the 6th “Toulon-Verona Conference Quality in Higher Education, Health Care, Local Government”, Oviedo, Spain, 10–11–12 September 2003. p. 265–273.

Demartini C, Mella P. Beyond feedback control: the interactive use of performance management systems. Implications for process innovation in Italian healthcare organisations. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2014;29(1):1–30.

Macinati MS. The relationship between quality management systems and organisational performance in the Italian national health service. Health Policy. 2008;85(2):228–41.

Adinolfi P. Barriers to reforming healthcare: the Italian case. Health Care Anal. 2014;22(1):36–58.

Pereira MA, Ferreira DC, Figueira JR, Marques RC. Measuring the efficiency of the Portuguese public hospitals: a value modelled network data envelopment analysis with simulation. Expert Syst with Appl. 2021;181:115169.

De Bono S, Heling G, Borg MA. Organisational culture and its implications for infection prevention and control in healthcare institutions. J Hosp Infect. 2014;86(1):1–6.

Bangaly K, Kweku-Muata O. Examining influence of national culture on individuals’ attitude and use of information and communication technology: assessment of moderating effect of culture through cross countries study. Int J Inform Manage. 2013;33(3):441–52.

Sánchez-Franco MJ, Martínez-López FJ, Martín-Velicia FA. Exploring the impact of individualism and uncertainty avoidance in web-based electronic learning: an empirical analysis in European higher education. Comput Educ. 2009;52(3):588–98.

Huang KY, Choi N, Chengalur-Smith IN. Cultural dimensions as moderators of the UTAUT model: a research proposal in a healthcare context. AMCIS; 2010. p. 188. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2010/188.

Armstrong N. What leads to innovation in mental healthcare? Reflections on clinical expertise in a bureaucratic age. BJPsych Bull. 2018;42(5):184–7.

Johnson A, Nguyen H, Groth M, Wang K, Ng JL. Time to change: a review of organisational culture change in health care organisations. J Organ Eff. 2016;3(3):265–88.

Lu CH, Hsiao JH, Chen RC. Factors determining nurse acceptance of hospital systems. Comput Inform Nurs. 2012;30(5):257–64.

Escobar-Rodriguez T, Romero-Alonso MM. Modeling nurses’ attitude toward using automated unit-based medication storage and distribution systems: an extension of the technology acceptance model. Comput Inform Nurs. 2013;31(5):235–43.

Pai FY, Huang KI. Applying the technology acceptance model to the introduction of healthcare information systems. Technol Forecast Soc. 2011;78(4):650–60.

Justice J. The bureaucratic context of international health: a social scientist’s view. Soc Sci Med. 1987;25(12):1301–6.

Scott TIM, Mannion R, Davies HT, Marshall MN. Implementing culture change in health care: theory and practice. Int J Qual Health Care. 2003;15(2):111–8.

Scott T, Mannion R, Marshall M, Davies H. Does organisational culture influence health care performance? A review of the evidence. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2003;8(2):105–17.

Cameron KS, Quinn RE. Diagnosing and changing organizational culture: Based on the competing values framework. MA: Addison-Wesley;2011.

Quinn RE, Rohrbaugh J. A competing values approach to organisational effectiveness. Public Prod Rev. 1981;5:122–40.

Arfi WB, Nasr IB, Khvatova T, Zaied YB. Understanding acceptance of ehealthcare by iot natives and iot immigrants: an integrated model of UTAUT, perceived risk, and financial cost. Technol Forecast and Soc Change. 2020;163:120437.

Lega F, De Pietro C. Converging patterns in hospital organisation: beyond the professional bureaucracy. Health Policy. 2005;74(3):261–81.

Lok P, Rhodes J, Westwood B. The mediating role of organisational subcultures in health care organisations. J Health Organ Manag. 2011;25(5):506–25.

Meterko M, Mohr DC, Young GJ. Teamwork culture and patient satisfaction in hospitals. Med Care. 2004;42:492–8.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by the University of Naples Parthenope for the language editing, proofreading and for the article-processing charge.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CM wrote Background and Research model. RA wrote Methodology and Results and Data analysis and results. LL wrote Discussion. LL wrote Research implications, conclusions and limits. All authors reviewed the manuscript. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Concetta Metallo (CM), Ph.D., is an associate professor of Organization and Information Systems at University Parthenope, Naples, Italy. Her research interests are: technology adoption by organizations and usage behaviours, social media usage, e-government. She has participated as speaker in several international conferences, and she has published papers in journals such as BMC Health Services Research, Government Information Quarterly, Behaviour & Information Technology, Information Systems Management, Technological Forecasting and Social Change, Production Planning & Control, The Information Society.

Rocco Agrifoglio, PhD, is Associate Professor of Organization Studies and Management Information Systems at the University of Naples “Parthenope” (Naples, Italy). He has earned his PhD in Management and Business Administration from the same University and he has also been a visiting scholar at University of Westminster (London, UK) and University of Castilla-La Mancha (Ciudad Real, ES). His primary research interests are communities of practice, technology acceptance and usage, IS continuance, and e-court. He has participated as speakers in several international conferences and has published numerous papers in journals, including Journal of Computer Information Systems (JCIS), Information Systems Management (ISM), Behaviour & Information Technology (BIT), Production Planning & Control (PPC), and Technological Forecasting and Social Change (TFSC).

Luigi Lepore is Associate Professor of Business Administration at Parthenope University of Naples (Italy). He is Head of Studies of Administration and Organization Science and Public Management. He has been a Visiting Researcher at IE Business School (Madrid) and at Institute for Court Management (Williamsburg—USA). His research interests focus on corporate governance, financial distress, accounting and financial reporting, public accounting and public management. He teaches business administration, accounting and public management. He has participated as speaker in several international conferences, including annual congress of European Accounting Association, European Group of Public Administration, Italian Chapter of Information System, European Institute for Advanced Studies in Management and the European Academy of Management. He has published numerous articles in journals, including Business Strategy and the Environment, Journal of Management and Governance, Utilities Policy, BMC Health Services Research, Corporate Governance: The international journal of business in society, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Information System Management, Management Control and Financial Reporting.

Loris Landriani, PhD, is Associate Professor of Business Management at the Department of Business and Economic Studies of the Parthenope University of Naples. He is currently a professor of Business Administration and External Auditing. His research interests mainly concern local utilities, viewed from the perspective of government, control and evaluation. In particular, he has dealt with transport, water services, kindergartens and cultural heritage. He is the author of numerous national and international researches and publications on these topics.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study does not include any data on subjects, human material, or human data from patients. All the data were provided by voluntary answers to semi-structured interviews by the employees of the hospitals. Participants received information about the study verbally. Participants were informed that the study was voluntary, that they could drop out of the study without explanation at any time, and that confidentiality was guaranteed. Participants agreed to participate by responding to the interviews. The informed consent for study participation has been obtained.

The survey was presented and accepted by the Executive Board of the hospital. All the data were collected anonymously. All data material was stored in a database in the University of Naples Parthenope, with a high level of security. No other ethics approval was necessary to be compliant with the Italian regulation (D.Lgs. 101/2018 https://www.gazzettaufficiale.it/eli/id/2018/09/04/18G00129/sg).

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

The participants gave consent for direct quotes from their interviews to be used in this manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

The Measurement Scales and Factor loadings.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Metallo, C., Agrifoglio, R., Lepore, L. et al. Explaing users’ technology acceptance through national cultural values in the hospital context. BMC Health Serv Res 22, 84 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07488-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07488-3