Abstract

Background

The role of an advanced practice physiotherapist has been introduced in many countries to improve access to care for patients with hip and knee arthritis. Traditional models of care have shown a gender bias, with women less often referred and recommended for surgery than men. This study sought to understand if patient gender affects access to care in the clinical encounter with the advanced practice provider. Our objectives were: (1) To determine if a gender difference exists in the clinical decision to offer a consultation with a surgeon; (2) To determine if a gender difference exists in patients’ decisions to accept a consultation with a surgeon among those patients to whom it is offered; and, (3) To describe patients’ reasons for not accepting a consultation with a surgeon.

Methods

This was a prospective study of 815 patients presenting to a tertiary care centre for assessment of hip and knee arthritis, with referral onward to an orthopaedic surgeon when indicated. We performed a multiple logistic regression analysis adjusting for severity to address the first objective and a simple logistic regression analysis to answer the second objective. Reasons for not accepting a surgical consultation were obtained by questionnaire.

Results

Eight hundred and fifteen patients (511 women, 304 men) fulfilled study eligibility criteria. There was no difference in the probability of being referred to a surgeon for men and women (difference adjusted for severity = − 0.02, 95% CI: − 0.07, 0.02). Neither was there a difference in the acceptance of a referral for men and women (difference = − 0.05, 95% CI: − 0.09, 0.00). Of the 14 reasons for declining a surgical consultation, 5 showed a difference with more women than men indicating a preference for non-surgical treatment along with fears/concerns about surgery.

Conclusions

There is no strong evidence to suggest there is a difference in proportion of males and females proceeding to surgical consultation in the model of care that utilizes advanced practice orthopaedic providers in triage. This study adds to the evidence that supports the use of suitably trained alternate providers in roles that reduce wait times to care and add value in contexts where health human resources are limited. The care model is a viable strategy to assist in managing the growing backlog in orthopaedic care, recently exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip and knee is a disabling condition when in advanced stages [1, 2]. Total hip arthroplasty and total knee arthroplasty are successful surgical procedures undertaken to relieve pain and restore function. In Canada, more than 137,000 patients undergo such procedures annually [3], and yet, patients with advanced arthritis continue to experience significant delays in accessing care, specifically a consultation with an orthopaedic surgeon. A report published by the Fraser Institute shows orthopaedics as having some of the longest waits among 12 medical specialties in Canada [4]. Patients now face even longer waits due to the COVID-19 pandemic which saw hospitals directed to substantially reduce elective, but medically necessary, surgeries to preserve health care resources, resulting in a growing backlog in orthopaedic care globally [5,6,7,8].

Over the past decade, models of care utilizing advanced practice physiotherapists (APPs) to assess and prioritize patients have been adopted and spread to improve access and care for orthopaedic patients [9,10,11]. Research has shown that suitably trained physiotherapists in an advanced practice role improve access to care and add value to the clinic visit by identifying patients that require a consultation with a surgeon, and diverting those that do not, to alternate treatment options, and by providing patients with personalized education and advice [12,13,14,15,16,17]. Level of agreement between APPs and orthopaedic surgeons on diagnosis and care decisions has been found to be high, and patients are highly satisfied with the technical skills, personal manner, information received and APP visit overall [18,19,20,21,22]. While a large body of research has accumulated regarding the clinical effectiveness of the APP role in the UK, Canada, Australia, and other countries, there is currently no information on unintended negative consequences of the model of care which are necessary to explore for its sustainability.

The APP’s role in evaluating which patients require surgical consultation and which patients do not is a complex process that involves a detailed examination of patient characteristics and a discussion with the patient regarding their knowledge of OA and views on joint replacement [16, 23, 24]. Previous research exploring the rate of use of total joint replacement found that women were less likely to be recommended a surgical approach to care by their primary care physicians as well as orthopaedic surgeons [25,26,27]. Further, Borkhoff et al. demonstrated that gender bias influences elements of informed decision-making during the clinical encounter, with poorer physician performance when the patient was a woman, and less time given to women in the encounter [26]. These findings are concerning in that the APP is an additional point of assessment for patients with moderately advanced arthritis and the potential for gender bias exists. An important goal for the clinic visit with the advanced practice provider is that patients with similar clinical characteristics receive the same information and treatment options regardless of gender.

Since inception of our model of care, we have employed an evaluation strategy that uses both quality improvement methodology and formal research. As part of our quality approach, we conducted a retrospective review (unpublished) on patients presenting to the clinic between 2011 and 2014, where women appeared less likely to proceed to a consultation with a surgeon. This may have occurred for 1 of 2 reasons: either women were less likely to be recommended a consultation with a surgeon or, women were less likely to accept the referral. Due to gaps in clinical documentation, we were unable to identify if this reflected a gender disparity in utilization of specialty care; furthermore, that analysis did not take disease severity into account.

The advanced practice provider’s assessment integrates complex information across several aspects including clinical findings, functional status, and results of diagnostic imaging. It is important to understand what factors within these aspects predict the offer of a consultation with a surgeon and to examine gender as one of the factors that may influence treatment recommendations. Possible explanations for the gender gap include patient perceptions about surgery (and associated risks, benefits, and recovery), personal preferences, availability of social support, caregiving responsibilities, and the patient-provider interaction [24, 28, 29].

Study objectives

Our study had three objectives: (1) To determine if a gender difference exists in the clinical decision to offer a consultation with a surgeon; (2) To determine if a gender difference exists in patients’ decisions to accept a consultation with a surgeon among those patients to whom it is offered; and, (3) To describe patients’ reasons for not accepting a consultation with a surgeon. The conclusions will inform the development of mitigating strategies and be useful to decision-makers in Canada and other countries with Universal coverage and where access to care is a significant issue necessitating development of alternate models of care.

Methods

Study design

This prospective study analysed data from 815 consecutive patients fulfilling this study’s eligibility criteria and presenting to a tertiary care centre in Ontario, Canada for initial assessment of moderate to advanced hip and knee arthritis. Participation was voluntary and all participants provided informed consent. Approval for use of human subjects was obtained from the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre.

Setting and participants

Patients are referred to the tertiary care centre by primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician specialists for consideration of arthroplasty and undergo a comprehensive assessment with an advanced practice provider (Physiotherapist or Occupational Therapist) in the outpatient clinic within 4 weeks from referral. The advanced practice provider evaluates the patient’s condition and facilitates referral onward to an orthopaedic surgeon when indicated. Patients were eligible to participate in the study if they were attending the clinic for initial assessment and, the reason for referral indicated moderate to advanced hip and knee arthritis. Patients were excluded from the study if they were returning for a follow up visit, unable to independently complete questionnaires, and if they presented for second opinion on prior total hip or knee replacement which is an additional function of the clinic.

During the initial assessment, the advanced practice provider performs a history and physical examination and incorporates results from standardized patient reported and performance outcome measurement, and diagnostic tests. The providers discuss the results of the assessment and treatment options with the patient, and together with the patient, devise a management plan, including referral to an orthopaedic surgeon.

Advanced practice providers

These healthcare professionals are typically physiotherapists with advanced formal education (beyond entry to practice) and extensive orthopaedic experience. We have one occupational therapist among 6 physiotherapists in the role. The advanced practice providers function independently upon successful completion of a 3-month Practice Development Program which is a workplace-based structured learning process, with competency assessment utilizing tools developed at our centre and those developed by colleagues in Australia [13, 30, 31]. Advanced practice providers have an extended scope of practice and are equipped to order X-rays, laboratory tests, and other investigations through Medical Directives.

Standardized clinical prioritization

The advanced practice providers use a tool developed by our centre for prioritizing patients (the Severity Scoring System) which acts as a guide to interpreting findings across three main elements of the standardized assessment: clinical findings, functional findings, and radiological findings. The clinical and functional findings are scored across 4 severity levels (e.g. no findings, mild, moderate, and severe) and scored from a rating of 0 to 3. Clinical findings include a patient-reported standardized outcome measure for pain intensity, the P4 [32]. Functional findings include results from the following standardized outcome measures recommended in the assessment of patients with hip and knee OA: patient-reported function with the Lower Extremity Functional Scale (LEFS); 30s Chair Stand Test; 40 m Fast Paced Walk Test; and, Timed Up and Go in lower functioning patients [33]. Radiological findings are scored across 3 severity levels (e.g. no findings, mild/moderate, and marked/advanced) and scored from a rating of 0 to 2 given the known lack of association between radiological findings and pain and disability [34]. The data coding for radiological findings had 4 categories (Kellgren-Lawrence grade) [35]. The Total Severity Score out of 8 is then aligned with urgency and priority levels to assist the clinician in determining an appropriate management plan.

Reasons for declining surgical consultation and surgery

The project team developed a simple questionnaire for participants declining the offer of surgical consultation to indicate their reasons for not proceeding, so as to explore patient preferences as a potential factor in gender disparity (see Additional file 1). The list of reasons was informed by the literature and confirmed with patients through an initial trial period until saturation in items was reached [24, 29, 36].

Data analysis

We summarized data as frequency counts and percentages, means and standard deviations or quartiles depending on the data’s parametric properties. For the first objective that addresses a potential gender difference in the patients referred forward, we performed three logistic regression analyses with the dependent variable being the decision to refer to surgeon (yes, no). Gender was the only independent variable in the first analysis. The second analysis examined the effect of gender having adjusted for joint type, age, radiological findings, P4, LEFS, 30s Chair Stand Test, and trial of conservative treatment. The third analysis examined the effect of gender having adjusted for the total severity score. We applied a simple logistic regression analysis for the second objective that examined a gender difference in the proportion of patients accepting a referral with the orthopaedic surgeon. We estimated gender specific probabilities of referral (1st objective) and acceptance (2nd objective), and their 95% confidence intervals. We applied a critical p-value of 0.05 for hypotheses tests. Data were analyzed using STATA v16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, Texas).

Objective 1: Sample size estimates for multiple logistic regression analyses are typically estimated by considering the expected number of events per variable (EPV) [37]. Our sample size estimate was based on 8 independent variables (7 covariates plus gender), 20 events per variable, and 20% of patients not being referred forward. These assumptions produced a sample size of 800 patients. Objective 2: We anticipated that 85% of patients offered a consultation with the surgeon would accept. The assumptions for the sample size calculation were: Type 1 error 0.05 2-tailed; Type II error 0.20; anticipated proportion of patients accepting referral in the larger proportion group = 0.90; anticipated difference in proportion 0.10 (i.e., smaller proportion = 0.80). These assumptions yielded a sample size of 398 patients.

Results

Eight hundred fifteen patients (511 women, 304 men) fulfilled our study’s eligibility criteria. Table 1 provides a summary of the participants’ characteristics and sample sizes when data were available for fewer than the entire sample. Women and men were of similar age and BMI. Women and men also had similar clinical, functional, and radiological severity scores. As would be expected, men had slightly faster times for the performance measures.

Three analyses—one unadjusted and two adjusted—were performed to estimate the probabilities of women and men being referred to a surgeon (Table 2). All three analyses yielded between gender differences that were neither statistically significant (p > 0.05) nor met our a priori specification of an important difference (i.e., a difference in proportions > 0.10). For the unadjusted analysis the proportion of women offered a surgical referral was 0.75 (382/511) compared to 0.79 (241/304) for men (difference = − 0.04, 95% CI: − 0.10, 0.01). Six hundred sixty-two patients (404 women, 258 men) had complete data for the analysis that adjusted for joint, age, Kellgren-Lawrence score, P4 score, LEFS score, 30s chair stand score, trial of conservative treatment. The adjusted probability of being referred to a surgeon was virtually identical for women and men (difference = − 0.01, 95% CI: − 0.06, 0.04). For the analysis that adjusted for Total Severity Score, complete data were available for 814 patients (510 women, 304 men). Once again, the adjusted probabilities of being referred to a surgeon were nearly identical for women and men (difference = − 0.02, 95% CI: − 0.07, 0.02).

Our second objective was to determine if there was a difference in the proportion of women and men accepting a referral to a surgeon. Of the 815 patients assessed, 609 were offered a referral (Table 3). The proportion of women accepting a surgical referral was 0.88 (329/373) compared to 0.93 (219/236) for men. This difference (difference = − 0.05, 95% CI: − 0.09, 0.00) was neither statistically significant (p > 0.05) nor did it meet our standard for an important between gender difference of |0.10|.

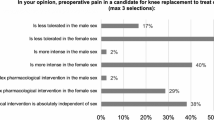

Table 4 summarizes the reasons for not accepting a surgical referral. Five items where the endorsement proportions differed by 0.10 or more and their respective confidence intervals excluded zero were: prefer no surgery, prefer non-surgical treatments, afraid of surgery, surgery may not help or may make worse; and, burden on others.

Discussion

Our study has shown that there was no difference in the probability of being referred to a surgeon for men and women with hip and knee arthritis by advanced practice orthopaedic providers in a tertiary care setting. This finding adds support for the model of care as a pathway to optimize access to care and treatment. At the core of this research is an inquiry into whether there is gender disparity in patients referred to surgeons by advanced practice providers as potentially indicated in our previous research. Gender disparity, due to gender bias influencing clinical decision-making, is well documented in traditional routes of care for patients with hip and knee arthritis, with women less often referred for surgical consultation and surgical treatment [25, 27, 38, 39]. In addition, the patient-physician interaction is known to be suboptimal for women with respect to informed decision-making and physician interpersonal behaviour [26]. In our model of care utilizing appropriately qualified and trained alternate advanced practice providers, women were not disadvantaged in receiving care.

It is interesting to note that 5 of the 14 reasons for declining a consultation with a surgeon show a gender difference: more women than men indicated a preference for non-surgical treatment along with fears/concerns about surgery. Additionally, women indicated they did not want to be a burden on others. These findings substantiate what has been documented in prior research; women wait longer for surgery, are fearful, and are concerned for their caregiving roles [29, 40]. These are important points of discussion when presenting treatment options to women. Women hesitant regarding surgery may require additional medical information (risks and benefits of surgery), information regarding the recovery trajectory and how much help/what sort of help would be needed following surgery, in addition to when usual activities can be resumed. These topics are key elements of informed decision making which was shown to be lacking in the traditional model of care, particularly in clinical encounters with women [26, 41]. While informed decision making was not specifically examined in the current study, the advanced practice providers are trained to encourage participation in the discussion regarding treatment options and explore patient preferences, and have additional clinical time to do so; furthermore, these providers are trained to gauge patient understanding. These enhancements to the traditional model of care likely improve the quality of the assessment and contribute to our study findings.

Equitable access to care through standardized assessment is the rationale for implementation of this model of care in Ontario, Canada [13, 42]. The model of care includes supporting elements that are integral to its performance such as standardized role entry qualifications, standardized training with competency assessment, standardized clinical assessments, and the incorporation of outcome measurement – both patient reported and performance measures, in addition to an emphasis on shared decision-making regarding treatment options that include self-management and non-surgical best practice recommendations. The model of care, as designed, does not appear to negatively impact women in accessing a surgical consultation or surgical treatment, and continues to show promise as a sustainable strategy that improves access to quality care and adds value when utilizing experienced healthcare professionals with a complementary skillset in triage.

Wait times have been made worse by the COVID-19 pandemic and a backlog of elective surgeries is now experienced in many countries that were forced to pause non urgent services to maintain health system capacity. The model of care is a viable strategy to address the backlog in orthopaedic care through effective prioritization of patients, and is consistent with service recovery recommendations [43]. In countries with universal health care systems, alternate models of care such as this are required to assist with resumption of services and improving access to care.

Limitations

This study is the first to look at gender bias in a model of care utilizing alternate orthopaedic providers, and as such makes an important contribution to the body of literature on models of care in orthopaedics and arthritis. A potential limitation of the study is that it was conducted in a single academic hospital (the developers of the model of care) in Ontario; however, results can be generalized to other sites that have applied and maintained the key characteristics of the model of care. This team has had particular interest in gender bias and shared decision-making. If bias were found in these advanced practice providers, then it’s likely that similar or greater bias would be found in advanced practice providers elsewhere and would warrant further exploration and mitigating strategies. The advanced practice providers were aware of the study objectives; which, in addition to the team’s special interest in gender bias, likely contributed to the positive outcome. Further research examining shared decision-making would be beneficial to examine with advanced practice providers.

Conclusion

Gender does not appear to play a role in access to care when patients are assessed by experienced, suitably-trained advanced practice providers suggesting an improvement in the quality of the assessment and patient-clinician interaction from the traditional model of care.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- APP:

-

Advanced practice physiotherapist

- LEFS:

-

Lower Extremity Functional Scale

- BMI:

-

Body Mass Index

References

McDonough C, Jette A. The contribution of osteoarthritis to functional limitations and disability. Clin Geriatr Med. 2010;26(3):387–99.

Hawker GA, Croxford R, Bierman AS, Harvey PJ, Ravi B, Stanaitis I, et al. All-Cause Mortality and Serious Cardiovascular Events in People with Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis: A Population Based Cohort Study. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3):e91286.

Canadian Institute for Health Information. Hip and Knee Replacements in Canada: CJRR Annual Statistics Summary, 2018–2019, Canadian joint replacement registry (CJRR) annual report. Ottawa: CIHI; 2020.

Bacchus B, Moir M. Waiting your turn: Wait times for Health Care in Canada, 2020 Report; 2020.

Bedard NA, Elkins JM, Brown TS. Effect of COVID-19 on Hip and Knee Arthroplasty Surgical Volume in the United States. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35(7):S45–8.

Thaler M, Khosravi I, Hirschmann MT, Kort NP, Zagra L, Epinette JA, et al. Disruption of joint arthroplasty services in Europe during the COVID-19 pandemic: an online survey within the European Hip Society (EHS) and the European Knee Associates (EKA). Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthroscopy. 2020;28(6):1712–9.

Carr A, Smith JA, Camaradou J, Prieto-Alhambra D. Growing backlog of planned surgery due to covid-19. BMJ. 2021;372:n339.

Wang J, Vahid S, Eberg M, Milroy S, Milkovich J, Wright FC, et al. Clearing the surgical backlog caused by COVID-19 in Ontario: a time series modelling study. Can Med Assoc J. 2020;192(44):E1347–56.

Desmeules F, Roy J-S, MacDermid JC, Champagne F, Hinse O, Woodhouse LJ. Advanced practice physiotherapy in patients with musculoskeletal disorders: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2012;13(1):107.

Samsson KS, Grimmer K, Larsson MEH, Morris J, Bernhardsson S. Effects on health and process outcomes of physiotherapist-led orthopaedic triage for patients with musculoskeletal disorders: A systematic review of comparative studies. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):673.

Fennelly O, Blake C, FitzGerald O, Breen R, O’Sullivan C, O’Mir M, et al. Advanced musculoskeletal physiotherapy practice in Ireland: A National Survey. Musculoskeletal Care. 2018;16(4):425–32.

Daker-White G, Carr A, Harvey I, et al. A randomized controlled trial. Shifting boundaries of doctors and physiotherapists in orthopaedic outpatient departments. J Epidemiol Community. 1999;53(10):643–50.

Robarts S, Kennedy D, MacLeod A, et al. A framework for the development and implementation of an advanced practice role for physiotherapists that improves access and quality of care for patients. Healthc Q. 2008;11(2):67–75.

Aiken A, Harrison M, Atkinson M, et al. Easing the burden for joint replacement wait times: the role of the expanded practice physiotherapist. Healthc Q. 2008;11(2):62–6.

MacKay C, Davis AM, Mahomed N, Badley EM. Expanding roles in orthopaedic care: A comparison of physiotherapist and orthopaedic surgeon recommendations for triage. J Eval Clin Pract. 2009;15(1):178–83.

Macintyre NJ, Johnson J, Macdonald N, Pontarini L, Ross K, Zubic G, et al. Characteristics of people with hip or knee osteoarthritis deemed not yet ready for total joint arthroplasty at triage. Physiother Can. 2015;67(4):369–77.

Fennelly O, Blake C, Fitzgerald O, Breen R, Ashton J, Brennan A, et al. Advanced practice physiotherapy-led triage in Irish orthopaedic and rheumatology services: National data audit. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018;19(1):181.

Razmjou H, Robarts S, Kennedy D, McKnight C, MacLeod AM, Holtby R. Evaluation of an advanced-practice physical therapist in a specialty shoulder clinic: Diagnostic agreement and effect on wait times. Physiother Can. 2013;65(1):46–55.

Robarts S, Stratford P, Kennedy D, Malcolm B, Finkelstein J. Evaluation of an advanced-practice physiotherapist in triaging patients with lumbar spine pain: Surgeon-physiotherapist level of agreement and patient satisfaction. Can J Surg. 2017;60(4):266–72.

Kennedy DM, Robarts S, Woodhouse L. Patients are satisfied with advanced practice physiotherapists in a role traditionally performed by orthopaedic surgeons. Physiother Can. 2010;62(4):298–305.

Lowry V, Bass A, Lavigne P, Léger-St-Jean B, Blanchette D, Perreault K, et al. Physiotherapists’ ability to diagnose and manage shoulder disorders in an outpatient orthopedic clinic: results from a concordance study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2020;29(8):1564–72.

Madsen MN, Kirkegaard ML, Klebe TM, Linnebjerg CL, Villumsen SMR, Due SJ, et al. Inter-professional agreement and collaboration between extended scope physiotherapists and orthopaedic surgeons in an orthopaedic outpatient shoulder clinic – a mixed methods study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2021;22(1):4.

Hudak PL, Clark JP, Hawker GA, Coyte PC, Mahomed NN, Kreder HJ, et al. “You’re perfect for the procedure! Why don’t you want it?” Elderly arthritis patients’ unwillingness to consider total joint arthroplasty surgery: A qualitative study. Medical Decision Making. 2002;22(3):272–8.

Frankel L, Sanmartin C, Conner-Spady B, Marshall DA, Freeman-Collins L, Wall A, et al. Osteoarthritis patients’ perceptions of “ appropriateness” for total joint replacement surgery. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2012;20(9):967–73.

Hawker GA, Wright JG, Coyte PC, Williams JI, Harvey B, Glazier R, et al. Differences between Men and Women in the Rate of Use of Hip and Knee Arthroplasty. New England J Med. 2000;342(14):1016–22.

Borkhoff CM, Hawker GA, Kreder HJ, Glazier RH, Mahomed NN, Wright JG. Influence of patients’ gender on informed decision making regarding total knee arthroplasty. Arthritis Care Res. 2013;65(8):1281–90.

Borkhoff CM, Hawker GA, Kreder HJ, Glazier RH, Mahomed NN, Wright JG. The effect of patients’ sex on physicians’ recommendations for total knee arthroplasty. CMAJ. 2008;178(6):681–7.

Hawker GA, Wright JG, Badley EM, Coyte PC. Perceptions of, and willingness to consider, total joint arthroplasty in a population-based cohort of individuals with disabling hip and knee arthritis. Arthritis Care Rese. 2004;51(4):635–41.

Karlson EW, Daltroy LH, Liang MH, Eaton HE, Katz JN. Gender differences in patient preferences may underlie differential utilization of elective surgery. Am J Med. 1997;102(6):524–30.

Harding P, Prescott J, Sayer J, Pearce A. Advanced musculoskeletal physiotherapy clinical education framework supporting an emerging new workforce. Aust Health Rev. 2015;39(3):271–82.

Harding PA, Pearce A. Advanced musculoskeletal physiotherapy in public hospitals: utilizing a competency based training and assessment approach. Physiotherapy. 2015;101:e1184.

Spadoni GF, Stratford PW, Solomon PE, Wishart LR. The Evaluation of Change in Pain Intensity: A Comparison of the P4 and Single-Item Numeric Pain Rating Scales. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2004;34(4):187–93.

Dobson F, Hinman RS, Roos EM, Abbott JH, Stratford P, Davis AM, et al. OARSI recommended performance-based tests to assess physical function in people diagnosed with hip or knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013;21(8):1042–52.

Dieppe PA, Cushnaghan J, Shepstone L. The Bristol “OA500” Study: Progression of osteoarthritis (OA) over 3 years and the relationship between clinical and radiographic changes at the knee joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1997;5(2):87–97.

Kellgren J, Lawrence J. Radiological assessment of osteoarthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1957;16:494–502.

Hawker G, Frankel L, Freeman-Collins L, Marshall D, Conner-Spady B, SanMartin C. Osteoarthritis patients’ perceptions regarding appropriateness for total joint replacement surgery. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18,S40.

Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, Holford TR, Feinstem AR. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(12):1373–9.

Borkhoff CM, Hawker GA, Wright JG. Patient gender affects the referral and recommendation for total joint arthroplasty. In: Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research; 2011.

Mota REM, Tarricone R, Ciani O, Bridges JFP, Drummond M. Determinants of demand for total hip and knee arthroplasty: A systematic literature review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12(1):225.

Katz JN, Wright EA, Guadagnoli E, Liang MH, Karlson EW, Cleary PD. Differences between men and women undergoing major orthopedic surgery for degenerative arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1994;37(5):687–94.

Braddock CH, Edwards KA, Hasenberg NM, Laidley TL, Levinson W. Informed decision making in outpatient practice: Time to get back to basics. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;282(24):2313–20.

Winter Di Cola J, Juma S, Kennedy D, Dickson P, Denis S, Robarts S, Gollish J, Webster F. Patients' perceptions of navigating "the system" for arthritis management: are they able to follow our recommendations? Physiother Can. 2014;66(3):264–71. https://doi.org/10.3138/ptc.2012-66.

Cisternas AF, Ramachandran R, Yaksh TL, Nahama A. Unintended consequences of COVID-19 safety measures on patients with chronic knee pain forced to defer joint replacement surgery. Pain Rep. 2020;5(6):e855. https://doi.org/10.1097/PR9.0000000000000855.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge Leslie Corrigan, APP; and, James Falconer, physiotherapy assistant for their commitment to excellence in patient care and to this study. We thank James Falconer and Hajra Imam for assistance with data collection and data entry; and, Rachel Kagan, our Patient Research Partner, for valued insight throughout the project.

Funding

Funding for the study was obtained through the Practice Based Research grant competition at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre. The funding body does not have a role in the design of the study, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data, or in the writing of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SR, SD, DK, and PS made substantial contributions to the conception and design of the study, data analysis, and drafting the manuscript. PS provided statistical analysis, interpretation of data, and prepared Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4. PD, SJ, VP, MR, and DBS made substantial contributions to the study’s conception and design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All study participants provided informed consent. Approval for use of human subjects was obtained from the Research Ethics Board of the Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre, #346–2019. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1.

Patient Questionnaire: Reasons for not proceeding to see a surgeon.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Robarts, S., Denis, S., Kennedy, D. et al. Patient gender does not influence referral to an orthopaedic surgeon by advanced practice orthopaedic providers: a prospective observational study in Canada. BMC Health Serv Res 21, 952 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06965-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-06965-5