Abstract

Background

Residents have to learn to provide high value, cost-conscious care (HVCCC) to counter the trend of excessive healthcare costs. Their learning is impacted by individuals from different stakeholder groups within the workplace environment. These individuals’ attitudes toward HVCCC may influence how and what residents learn. This study was carried out to develop an instrument to reliably measure HVCCC attitudes among residents, staff physicians, administrators, and patients. The instrument can be used to assess the residency-training environment.

Method

The Maastricht HVCCC Attitude Questionnaire (MHAQ) was developed in four phases. First, we conducted exploratory factor analyses using original data from a previously published survey. Next, we added nine items to strengthen subscales and tested the new questionnaire among the four stakeholder groups. We used exploratory factor analysis and Cronbach’s alphas to define subscales, after which the final version of the MHAQ was constructed. Finally, we used generalizability theory to determine the number of respondents (residents or staff physicians) needed to reliably measure a specialty attitude score.

Results

Initial factor analysis identified three subscales. Thereafter, 301 residents, 297 staff physicians, 53 administrators and 792 patients completed the new questionnaire between June 2017 and July 2018. The best fitting subscale composition was a three-factor model. Subscales were defined as high-value care, cost incorporation, and perceived drawbacks. Cronbach’s alphas were between 0.61 and 0.82 for all stakeholders on all subscales. Sufficient reliability for assessing national specialty attitude (G-coefficient > 0.6) could be achieved from 14 respondents.

Conclusions

The MHAQ reliably measures individual attitudes toward HVCCC in different stakeholders in health care contexts. It addresses key dimensions of HVCCC, providing content validity evidence. The MHAQ can be used to identify frontrunners of HVCCC, pinpoint aspects of residency training that need improvement, and benchmark and compare across specialties, hospitals and regions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Providing high value, cost-conscious care (HVCCC) is critical to improve the value of health care and at the same time counter rising costs, eliminate wasted spending, and reduce overuse (provision of healthcare services with no medical basis or for which harms equal or exceed benefit) [1,2,3,4,5]. Value in this context can be understood as quality divided by cost over time [6]. Cost-conscious refers to the awareness an individual has on the specific expenses and cost-effectiveness of an intervention, as well as negative consequences as a result of providing – or not providing - an intervention, like patient dissatisfaction [7, 8]. Providing HVCCC requires physicians to balance the potential benefits and harms of a test or treatment, while simultaneously considering costs and possible drawbacks [7]. Physician practice patterns influence the number and type of healthcare services patients receive [9]. The post-graduate training appears to be particularly formative in shaping residents’ current and future behaviors related to high-value care, such as during exposure to faculty discussions on patient care [10]. Medical education thus has an obligation to ensure that stakeholders within the post-graduate learning environment support the development of HVCCC practice patterns [11,12,13,14,15,16,17].

Learning environments are complex, involving personal, social, organizational, physical, and virtual components [18]. Multiple individuals from different stakeholder groups contribute to the creation of workplace environments, and the attitudes of these individuals may influence an organizations’ culture regarding how and what residents learn [19,20,21,22,23]. Attitudes are also important (albeit imperfect) predictors of individual behavior [24], as evidenced by multiple studies showing associations between physician attitudes and beliefs and their utilization of healthcare services [25,26,27,28]. Understanding the attitudes of key stakeholders thus has the potential to offer valuable insights into the post-graduate training environment [29], but there is a scarcity of reliable tools to measure individual attitudes on all dimensions of HVCCC.

In post-graduate medical training, staff physicians, administrators and patients shape residents’ recognition and understanding of HVCCC’s necessity [15, 17, 30,31,32]. While different stakeholders can have different preferences regarding the provision of HVCCC, measuring all stakeholders’ attitudes can give insight in the resident’s workplace environment regarding the different dimensions of providing HVCCC. Prior studies have tried to measure the attitudes of particular stakeholder groups with respect to specific dimensions of HVCCC [8, 10, 23, 32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39]. However, a single reliable instrument to measure the individual attitudes of all these stakeholder groups toward multiple dimensions of providing HVCCC has not yet been developed. Such an instrument could both assess attitudes at the individual level and compare attitudes between stakeholders on distinct dimensions. It also enables comparisons among different units, organizations, and specialties on the dimensions of providing HVCCC.

This study aims to a) develop an instrument, the Maastricht HVCCC-Attitudes Questionnaire (MHAQ), to measure resident, staff physician, administrator and patient attitudes toward HVCCC and b) determine, using generalizability (G) theory [40], how many respondents are needed to reliably measure a specialty attitude score on a national level.

Method

We reviewed the literature to identify existing instruments for assessing individual attitudes toward HVCCC. From these, we selected items from the questionnaire used by Leep Hunderfund et al. [36] in their study of medical student attitudes toward cost-conscious care. These items were based on previously published surveys of practicing physicians and focus groups interviews with physicians, who gave input and suggestions on the items, as well as on reviews of the literature on cost-conscious care with input from various field experts [8, 33,34,35], supporting its content validity [41]. For more details on the development of the items, see the study by Leep Hunderfund et al. [36]. However, the concept of HVCCC consists of three key dimensions. Next to cost-conscious care and potential drawbacks, containing both the direct cost-effectiveness and downstream consequences of including cost-effectiveness, also the provision of value needs to be addressed [7]. Furthermore, because results were reported on an item level, underlying constructs needed to be explored in order to methodologically interpret and compare results of different stakeholders.

We developed the MHAQ through a four-phase process (Fig. 1):

-

1)

Investigating subscales of cost-conscious care, using items and original data from the survey conducted by Leep Hunderfund, et al. [36].

-

2)

Adding items, which include the value dimension, to strengthen subscales, and adapting items for use by residents, staff physicians, administrators, and patients.

-

3)

Testing items among four samples of these stakeholders and developing the final version of the MHAQ.

-

4)

Assessing the number of respondents per specialty on a national level needed to reliably measure a specialty attitude score through generalizability analysis.

Phase 1: investigating subscales

Questionnaire and data

We used items from the aforementioned published survey of U.S. medical students as the starting point for questionnaire development, as this survey derived their 21 items assessing individual attitudes toward cost-conscious care, on recently published surveys for practicing physicians [36]. The authors used a four-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree).

Analysis

Since we developed a new scale without having a priori hypotheses about the structure of the variables, we used exploratory factor analysis (principle component analysis, PCA) to examine the structure of these 21 survey items and to define subscales. PCA maximizes explained variance of the items [42] and is considered suitable when examining new constructs [43, 44]. Varimax rotation was performed to maximize spread of all factors, resulting in better interpretable factors [42]. We used a parallel analysis, the Kaiser Guttman criterion (eigenvalues > 1) and inspection of the scree plot, to identify the optimal number of factors [45]. We tested internal-consistency reliability of constructs using Cronbach’s alpha [46].

Phase 2: preparing the MHAQ

Additional items

Based on the internal-consistency reliability of identified subscales (which were around 0.6) and to tailor the MHAQ to new stakeholders and a new context, we added nine items to the original questionnaire. Because the initial 21 items focused primarily on costs, new items focused on value (e.g., risks and benefits of treatment, consideration of patient values) given the importance of value in HVCCC. These items were based on items described in the context of validated surveys on high-value originating from experts in the field [10, 23, 39, 47].

Different stakeholders

We developed a parallel questionnaire for medical residents, staff physicians and administrators. Items for patients were identical in content, but formulated for a lay audience. Additionally, we added a fifth answering option (‘I don’t know’) for patients, to prevent random answering when questions were not well understood. These items were pilot-tested with 56 patients in 4 cycles to refine formulations.

Different context

For usage in a Dutch context, we translated all items into Dutch. A professional translator translated all items back into English to evaluate similarity between the original source and translated items [48].

Phase 3: administering the MHAQ and developing the final version

Data collection

To recruit respondents, we approached hospital educational committees from all academic training regions (n = 8) in the Netherlands. Willing members of the hospital educational committees recruited medical residents and staff physicians to participate in the study. Additionally, we approached residents and staff physicians through the periodic newsletter of the ‘Bewustzijnsproject’, a Dutch project promoting HVCCC on a national level. The last authors (F.S. and L.S.) approached administrators (policy and/or financial) in several hospitals. We approached patients before and after patient consults, after gaining (ethical) approval by the relevant hospital and the physician in charge of the department, and via several patient platforms. We sent all invitations to complete the MHAQ between June 2017 and July 2018. Participants received an information letter, after which they signed an informed consent form before answering the questionnaire. Medical residents, staff physicians and administrators filled out the questionnaire online via Qualtrics, a survey software program. Patients also had the option to answer the questionnaire on hardcopy.

Analysis

We analyzed data following the same procedure as in Phase 1. We analyzed data from all stakeholder groups separately, after which an optimal solution was determined through a parallel analysis, as well as examination of each of the scree-plots and the Kaiser-Guttman criterion, followed by an inspection of the factor loadings. We calculated internal consistency reliability of constructs separately for all subscales and all stakeholders using Cronbach’s alpha. Since we developed new scales, a Cronbach’s alpha > 0.6 was considered acceptable [49].

Phase 4: generalizability analysis

We conducted a generalizability analysis [50] to assess the number of respondents needed to reliably measure a shared attitude score toward HVCCC of residents and staff physicians by specialty on a national level. We used Levene’s homogeneity tests to determine equal variances between specialties of different hospitals. In terms of generalizability theory, we performed a single facet analysis with attitude scores nested within specialties. We carried out a variance component analysis, using specialty as random factor and attitude score as dependent factor. We estimated the variance associated with specialties and the variance of attitude scores nested within specialties using the following formula:

in which Vs is the associated variance of specialties, Vp:s is the associated variance of a participants’ attitude score within specialties, and Np is the number of participants attitude scores. We used results from G-study variance components to estimate SEM and conduct D-studies to project reliability estimates for varying numbers of respondents. For feasibility, we accepted a G-coefficient greater than 0.6 [50]. All data were analyzed using IBM SPSS statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.).

Results

Phase 1

The dataset from the published study on cost-conscious care included responses from students at 10 medical schools geographically distributed across the U.S.. Nine of these schools granted permission to use de-identified data from their students for the purposes of this study (3195 responses of 5992 total students surveyed). No student identifiers were collected and we removed school identifiers prior to sharing. Results of PCA indicated a three subscale-model. All factors had eigenvalues above 1.5. The first subscale contained five items about the responsibility of physicians to provide/promote HVCCC (Table 1); the second subscale contained five items about the relationship of physicians and patients when implementing HVCCC; the final subscale contained four items about considering costs in clinical decision making. Cronbach’s alphas of the subscales were between 0.64 and 0.66. Seven items had factor loadings < .4, representing a low communality for these items, and were not included in these subscales. These items, however, were still included in phases 2 and 3.

Phase 2

Table 3 shows the nine new items we added in phase 2, indicated with an asterisk. After translation into Dutch language, content of the original source items and the translated items was identical. The resulting questionnaires for all stakeholder groups contained 30 items, including 21 items from the original questionnaire and nine newly added items.

Phase 3

In total, 301 residents and 297 staff-physicians completed the MHAQ. Residents and staff physicians worked in 31 different specialties and 32 hospitals, geographically distributed across the Netherlands. Fifty-three administrators and 521 patients completed the MHAQ. Administrators and patients came from five hospitals in the South of the Netherlands (Table 2).

Data analyses

To develop a questionnaire that is applicable to multiple stakeholders in postgraduate medical education and enables reliable comparisons between stakeholders, grouping of items per subscale has to be the same for all stakeholders. S.M. and K.K. determined a best-fitting subscale composition for all stakeholders, based on the inspection of factor structures for each of the stakeholders. When compromises were necessary, factor analyses of residents and staff-physicians were prioritized when creating optimal subscales for all stakeholders, since these groups are most central in post-graduate medical training. The best-fitting subscale composition for all stakeholders was a three-factor model. All factors had eigenvalues above 1. Four of five items of subscale 1 in phase 1 again clustered on the same factor, together with three additional items from the original subscale 3, as well as two items that had a low factor loading in phase 1 and one new item. The four items of subscale 2 in phase 1 again loaded all on the same factor. Three new items also loaded on this factor. The remaining item from subscale 3 loaded on a third factor, which also included one item from subscale 1, two items with low factor loadings in phase 1, and four new items. Thus, eight of the nine items added in phase 2 strengthened the subscales. All items in phase 1 focused on cost-conscious care, but in phase 3 some of these items loaded on high value care. This is due to the content of these items, which do contain a cost component, but are in essence statements on high value care. Because in phase 1 high value care was not evaluated, these items loaded in this phase on a different subscale. For the final subscale composition, we optimized Cronbach’s alphas for each stakeholder group, considering all subscales had to fit every stakeholder.

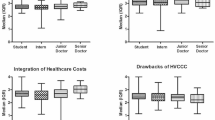

Final MHAQ

The aforementioned analyses resulted in 25 items distributed among three subscales, each covering an important dimension of HVCCC in clinical environments. We defined the labels of subscales in our team of experts, based on the main focus of the consisting items. Subscale 1, defined as high-value care, contained eight items about physicians’ provision of high value care (Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.61 for staff physicians to 0.77 for administrators). Subscale 2, defined as cost incorporation, contained 10 items about the integration of healthcare costs in physicians’ daily practice (Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.69 for staff physicians to 0.80 for patients). Subscale 3, defined as perceived drawbacks, contained seven items about perceived drawbacks of practicing HVCCC (Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.67 for residents to 0.82 for patients). Table 3 presents the final version of the MHAQ. (The survey instrument is available as supplementary file.)

Phase 4

Generalizability

This reliability estimation was performed separately for medical residents and staff physicians and for each subscale. Levene’s homogeneity tests indicated equal variances between specialties (e.g., cardiology, internal medicine) across different hospitals. Results from D-studies indicated the number of respondents needed to reliably measure (G-score ≥ 0.6) residents’ attitude score per specialty on a national level is 28 for the subscale high value care, 52 for the subscale cost incorporation, and 15 for the subscale perceived drawbacks. For staff physicians, the number of respondents needed was respectively 14 for the subscale high value care, 21 for the subscale cost incorporation, and 32 for the subscale perceived drawbacks. Figures 2 and 3 display an overview of the G-score per subscale for residents and staff physicians.

Discussion

This study describes the development of the MHAQ and provides reliability evidence supporting its use to measure attitudes toward HVCCC among important stakeholders in the post-graduate clinical learning environment. The MHAQ assesses three key dimensions of HVCCC and may be used to identify frontrunners who endorse and prioritize HVCCC, to pinpoint aspects of HVCCC that need to be improved or changed to better support HVCCC in the post-graduate learning environment, and to facilitate comparisons among different stakeholder groups, specialties, regions, and potentially hospitals or departments. The MHAQ includes three subscales relating to provision of high-value care (8 items), integration of costs (10 items), and perceived drawbacks of HVCCC (7 items). These subscales encompass all key dimensions of providing HVCCC in clinical practice [7], hence supporting the content validity of MHAQ scores.

Scores on high-value care reflect the degree to which individuals believe physicians should be responsible for limiting unnecessary testing, reducing waste, considering risks, benefits, and patient preferences when making diagnostic or therapeutic intervention decisions. High scores on this subscale can identify proponents of HVCCC who believe physicians should be frontrunners in the provision of high-value care. When key individuals within the clinical learning environment advocate high-value care, corresponding role modelling can help to shape future physicians’ HVCCC practice patterns [17, 30, 51].

Scores on cost incorporation reflect individual beliefs about the degree to which physicians should integrate costs in their daily clinical practice, for example when making treatment decisions or when discussing options with patients. Although physicians assume they contribute minimally to healthcare costs [35], they actually direct up to 87% of all healthcare spending [52]. Knowing physicians’ view on the incorporation of costs in their daily practice, together with patients’ view on the incorporation of costs, can be important starting points for transformation efforts to educate future physicians about providing HVCCC [14].

Scores on perceived drawbacks reflect individual beliefs about potential drawbacks of HVCCC, like patient dissatisfaction or risks of malpractice. Perceptions like these are known barriers to the implementation of HVCCC in practice [53] and drivers of unnecessary testing [54]. When individuals within the same organization have different perceptions of the drawbacks, incorporation of HVCCC in daily clinical practices is unsustainable. Pinpointing organizations as such could initiate aligned education programs for all stakeholders in that organization on the benefits of HVCCC, to create a common understanding and support of the delivery of HVCCC [17, 55].

Internal consistency reliability was sufficient for all stakeholders on all subscales. The internal consistency reliability for subscale scores was lower for residents and staff physicians than for patients and administrators. This could suggest that residents and physicians have more nuanced views on the provision of high-value care, integration of costs into clinical practice, and potential drawbacks of HVCCC. Alternatively, items formulated for a lay audience may be more evident in meaning and therefore clearer to answer than items used in the questionnaires for residents, staff physicians, and administrators. The patient version of the MHAQ thus has the potential to inform future improvement of subscale reliability for other stakeholders when developing the MHAQ further.

The MHAQ can not only be used to measure attitudes toward HVCCC at the individual level, but also to compare attitudes among larger groups, e.g. specialties, hospitals, regions. Our D-study results predict 14 to 52 respondents would be required to reliably assess HVCCC attitudes among resident or staff physicians, supporting the feasibility of group comparisons at the national, specialty level.

Strengths and limitations

This study has certain strengths and limitations. First, the MHAQ is based on a previously published questionnaire informed by a literature review on HVCCC, which was further enhanced through the addition of items (also based on the literature) that emphasized value as an important dimension in addition to cost and drawbacks. Future studies could provide additional content validity evidence for MHAQ scores by presenting items to subject matter experts, for example in a Delphi-study [56]. Second, while we are the first, to our knowledge, to simultaneously survey resident, staff physician, administrator, and patient attitudes toward HVCCC, our study did not include all potential stakeholders. Future studies could extend our work by including other relevant groups, such as nurses and other allied health professionals, who contribute to the clinical learning environment. Third, we used the same items in the U.S. and the Netherlands, which strengthens the broad usability of the MHAQ. However, healthcare delivery systems vary by country and MHAQ items may not be equally applicable in all settings. Fourth, while the final version of the MHAQ showed promising reliabilities, and D-studies support the feasibility of reliable assessments at the specialty level, there were too few results from a single department within a single hospital to calculate a reliable G-score at the department level. Further studies are needed to assess the number of respondents needed for a reliable department-level attitude score, which may most closely approximate the clinical learning environment experience by residents.

Conclusion

The MHAQ is a new instrument capable of reliably measuring attitudes toward HVCCC among individuals within multiple relevant stakeholder groups - residents, staff physicians, administrators, and patients - with subscales that address key dimensions of HVCCC. The MHAQ can be used to identify frontrunners who endorse and prioritize HVCCC, to pinpoint aspects of HVCCC that need to improved or changed to better support HVCCC in the post-graduate learning environment, and to facilitate comparisons among different stakeholder groups, specialties, regions, and potentially hospitals or departments.

Availability of data and materials

The Dutch dataset collected during the current study is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- D-studies:

-

Decision studies

- G-coefficient:

-

Generalizability coefficient

- G-score:

-

Generalizability score

- G-studies:

-

Generalizability studies

- HVCCC:

-

High-Value, Cost Conscious Care

- MHAQ:

-

Maastricht HVCCC Attitude Questionnaire

- PCA:

-

Principal Component Analysis

- SEM:

-

Standard Error of Measurement

- U.S.:

-

United States

References

American College of Physicians. Controlling health care costs while promoting the best possible health outcomes. Philadelphia: American College of Physicians; 2009: Policy Monograph. (Available from American College of Physicians, 190 N. Independence Mall West, Philadelphia, PA 19106.).

Fischer ES, Welch GH. Avoiding the unintended consequences of growth in medical care: how might more be worse? JAMA. 1999;281(5):446–53.

Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau. Meebetalen aan de zorg. In: Het ministerie van Volksgezondheid WeS, editor. Den Haag: Textcetera; 2012.

College Geneeskundige Specialismen. Bewustzijnsproject: Bewust kosteneffectief kwaliteit van zorg leveren in geneeskundig-specialistische vervolgopleidingen. 2015.

Morgan DJ, Brownlee S, Leppin AL, Kressin N, Dhruva SS, Levin L, et al. Setting a research agenda for medical overuse. BMJ. 2015;351:h4534.

Smoldt RK, Cortese DA. Pay-for-performance or pay for value? Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82:210–3.

Owens DK, Qaseem A, Chou R, Shekelle P. High-value, cost-conscious health care: concepts for clinicians to evaluate the benefits, harms, and costs of medical interventions. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:174–80.

Goold SD, Hofer T, Zimmerman M, Hayward RA. Measuring physician attitudes toward cost, uncertainty, malpractice, and utilization review. J Gen Intern Med. 1994;9:544–9.

Sirovich BE, Gallagher PM, Wennberg DE, Fisher ES. Discretionary decision making by primary care physicians and the cost of U.S. health care. Health Aff. 2008;27:813–23.

Ryskina KL, Smith CD, Weissman A, Post J, Dine JC, Bollman K, et al. U.S. internal medicine residents’ knowledge and practice of high-value care: a national survey. Acad Med. 2015;90(10):1373–9.

Cooke M. Cost consciousness in patient care-what is medical education's responsibility? N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1253–5.

King BC, Abramson E, DiPace J, Gerber L, Hammad H, Naifeh M. High value, cost-conscious care: perspective of pediatric faculty and residents. Acad Pediatr. 2016;16(6):e7.

Korenstein D. Charting the route to high-value care the role of medical education. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2359–61.

Weinberger SE. Educating trainees about appropriate and cost-conscious diagnostic testing. Acad Med. 2011;86(11):1352.

Weinberger SE. Providing high value cost-conscious care: A critical seventh general competency for physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:386–8.

Ryskina KL, Korenstein D, Weissman A, Masters P, Alguire P, Smith CD. Development of a high-value care subscore on the internal medicine in-training examination. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(10):733–9.

Stammen LA, Stalmeijer RE, Paternotte E, Oudkerk Pool A, Driessen EW, Scheele F, et al. Training physicians to provide high-value, cost-conscious care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2384–400.

Foundation JMJ. Improving environments for learning in the health professions. Atlanta: Macy Foundation Conference; 2018.

Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718–25.

Jarvis-Selinger S, Pratt DD, Regehr G. Competency is not enough: integrating identity formation into the medical education discourse. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1185–90.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1991;50:179–211.

Ajzen I. The theory of planned behaviour: reactions and reflections. Psychol Health. 2011;26(9):1113–27.

Gupta R, Moriates C, Harrison JD, Valencia V, Ong M, Clarke R, et al. Development of a high-value care culture survey: a modified delphi process and psychometric evaluation. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;0:1–9.

Armitage CJ, Conner M. Efficacy of the theory of planned behaviour: a meta-analytic review. Br J Soc Psychol. 2001;40:471–99.

Cutler D, Skinner JS, Stern AD, Wennberg DE. Physician beliefs and patient preferences: a new look at regional variation in health care spending. Am Econ J: Econ Policy. 2019;11(1):192–221.

Pearson SD, Goldman L, Orav EJ, Guadagnoli E, Garcia TB, Johnson PA, et al. Triage decisions for emergency department patients with chest pain: do physicians’ risk attitudes make the difference? J Gen Intern Med. 1995;10(10):557–64.

Tubbs EP, Broeckel Elrod JA, Flum DA. Risk taking and tolerance of uncertainty: implications for surgeons. J Surg Res. 2006;131:1–6.

Zaat JOM, van Eijk JTM. General Practitioners’ uncertainty, risk preference, and use of laboratory tests. Med Care. 1992;30(9):846–54.

Bhatia RS, Levinson W, Shortt S, Pendrith C, Fric-Shamji E, Kallewaard M, et al. Measuring the effect of choosing wisely: an integrated framework to assess campaign impact on low-value care. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(8):523–31.

Jochemsen-van der Leeuw HG, van Dijk N, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, Wieringa-de Waard M. The attributes of the clinical trainer as a role model: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88(1):26–34.

Finset A. Patient participation, engagement and activation: increased emphasis on the role of patients in healthcare. Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(7):1245–6.

Parand A, Dopson S, Renz A, Vincent C. The role of hospital managers in quality and patient safety: a systematic review. BMJ. 2014;4(9):e005055.

Hurst S, Slowther AM, Forde R, Pegoraro R, Reiter-Theil S, Perrier A, et al. Prevalence and determinants of physician bedside rationing. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:1138–43.

Kirchhoff AC, Hart G, Campbell EG. Rural and urban primary care physician professional beliefs and quality improvement behaviors. J Rural Health. 2014;30:235–43.

Tilburt JC, Wynia MK, Sheeler RD, Thorsteinsdottir B, James KM, Egginton JS, et al. Views of US physicians about controlling health care costs. JAMA. 2013;310(4):380–8.

Leep Hunderfund AN, Dyrbye LN, Starr SR, Mandrekar J, Naessens JM, Tilburt JC, et al. Role modeling and regional health care intensity: U.S. medical student attitudes toward and experiences with cost-conscious care. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):694–702.

Detsky AS. What patients really want from health care. JAMA. 2011;306(22):2500–1.

Weiner BJ, Shortell SM, Alexander J. Promoting clinical involvement in hospital quality improvement efforts: the effects of top management, board, and physician leadership. Health Serv Res. 1997;32(4):491–510.

Colla CH, Kinsella EA, Morden NE, Meyers DJ, Rosenthal MB, Sequist TD. Physician perceptions of choosing wisely and drivers of overuse. Am J Manag Care. 2016;22(5):337–43.

Hall C. Comment: generalizability theory and assessment in medical training. Neurology. 2015;85:1628.

Association AER, Association AP, Education NCoMi. Standards for educational and psychological testing. Washington, United States of America: American Educational Research Association; 2014.

Field A. Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics: sage; 2013.

McCoach DB, Gable RK, Madura JP. Instrument development in the affective domain: school and corporate applications. 3rd ed. New York: Springer; 2013.

Boateng GO, Neilands TB, Frongillo EA, Melgar-Quinonez HR, Young SL. Best practices for developing and validating scales for health, social, and behavioral research: a primer. Front Public Health. 2018;6:149.

O'Connor BP. SPSS and SAS programs for determining the number of components using parallel analysis and Velicer’s MAP test. Behav Res Methods Instrum Comput. 2000;32(3):396–402.

Etchegaray JM, Fischer W. Survey research: be careful where you step. BMJ Qual Saf. 2006;15(3):154–5.

American Board Of Internal Medicine Foundation. National physician survey. 2014.

Brislin RW. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J Cross-Cult Psychol. 1970;1(3):185–216.

Loewenthal K, Lewis CA. An introduction to psychological tests and scales. Philadelphia: Psychology press; 2015.

Bloch R, Norman G. Generalizability theory for the perplexed: a practical introduction and guide: AMEE Guide No. 68. Med Teach. 2012;34(11):960–92.

Colla CH, Sequist TD, Rosenthal MB, Schpero WL, Gottlieb DJ, Morden NE. Use of non-indicated cardiac testing in low-risk patients: choosing wisely. BMJ Qual Saf. 2014;24(2):149–53.

Tartaglia KM, Kman N, Ledford C. Medical student perceptions of cost-conscious care in an internal medicine clerkship: a thematic analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(10):1491–6.

Kanzaria HK, Hoffman JR, Probst MA, Caloyeras JP, Berry SH, Brook RH. Emergency physician perceptions of medically unnecessary advanced diagnostic imaging. Acad Emerg Med. 2015;22(4):390–8.

Bishop TF, Federman AD, Keyhani S. Physician views on defensive medicine a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170(12):1081–3.

Gupta R, Sehgal N, Arora VM. Aligning Delivery System and Training Missions in Academic Medical Centers to Promote High-Value Care. Acad Med. 2018.

Michels NRM, Denekens J, Driessen EW, Van Gaal LF, Bossaert LL, De Winter YD. A Delphi study to construct a CanMEDS competence based inventory applicable for workplace assessment. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):86.

Mordang SBR, Könings KD, Leep Hunderfund AN, Paulus ATG, Smeenk FWJM, Stassen LPS. A new instrument to measure attitudes regarding high value, cost-conscious care of healthcare stakeholders: development of the MHAQ. Vienna: Oral presentation at Association for Medical Education in Europe Annual Conference; 2019.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Angelique van Bijsterveld and Corry den Rooyen for their support and assistance with connecting to key individuals across the Netherlands, who were able to help with data collection. In addition, the authors are grateful for the help of all project leaders in different Dutch educational regions in administering the MHAQ to potential participants. This research study was presented as a research paper at the 2019 Annual AMEE (Association for Medical Education in Europe) Conference, Vienna, Austria, August 26, 2019 [57].

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.M. contributed to conception and design of the study, to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data in this study, and drafting and revising of the paper. He approves submission and publication of the paper and agrees with being accountable for all aspects thereof. K.K. contributed to conception and design of the study, to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of the data in this study, and substantial revising of different versions of the paper. She approves submission and publication of the paper and agrees with being accountable for all aspects thereof. A.L.H. contributed to the acquisition of the data in this study, and substantintial revising of different versions (of parts) of the paper. She approves submission and publication of the paper and agrees with being accountable for all aspects thereof. A.P. contributed to the analysis used in the paper and reviewing of different versions (of parts) of the paper. She approves submission and publication of the paper and agrees with being accountable for all aspects thereof. F.S. contributed to conception and design of the study, to the acquisition and interpretation of the data in this study, and substantial revising of different versions of the paper. He approves submission and publication of the paper and agrees with being accountable for all aspects thereof. L.S. contributed to conception and design of the study, to the acquisition and interpretation of the data in this study, and substantial revising of different versions of the paper. He approves submission and publication of the paper and agrees with being accountable for all aspects thereof. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethical Review Board (ERB) of the Netherlands Association for Medical Education (NVMO) approved this study (no. NERB814 and amendment no. NERB817) before launch.

Informed consent was asked from all participants in this study and all were given the opportunity to withdraw from participating in the study.

Consent for publication

All participants consented to their data being used anonymously.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

The Maastricht HVCCC Attitude Questionnaire (MHAQ).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mordang, S.B.R., Könings, K.D., Leep Hunderfund, A.N. et al. A new instrument to measure high value, cost-conscious care attitudes among healthcare stakeholders: development of the MHAQ. BMC Health Serv Res 20, 156 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4979-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-4979-z