Abstract

Background

Although benchmarking may improve hospital processes, research on this subject is limited. The aim of this study was to provide an overview of publications on benchmarking in specialty hospitals and a description of study characteristics.

Methods

We searched PubMed and EMBASE for articles published in English in the last 10 years. Eligible articles described a project stating benchmarking as its objective and involving a specialty hospital or specific patient category; or those dealing with the methodology or evaluation of benchmarking.

Results

Of 1,817 articles identified in total, 24 were included in the study. Articles were categorized into: pathway benchmarking, institutional benchmarking, articles on benchmark methodology or -evaluation and benchmarking using a patient registry. There was a large degree of variability:(1) study designs were mostly descriptive and retrospective; (2) not all studies generated and showed data in sufficient detail; and (3) there was variety in whether a benchmarking model was just described or if quality improvement as a consequence of the benchmark was reported upon. Most of the studies that described a benchmark model described the use of benchmarking partners from the same industry category, sometimes from all over the world.

Conclusions

Benchmarking seems to be more developed in eye hospitals, emergency departments and oncology specialty hospitals. Some studies showed promising improvement effects. However, the majority of the articles lacked a structured design, and did not report on benchmark outcomes. In order to evaluate the effectiveness of benchmarking to improve quality in specialty hospitals, robust and structured designs are needed including a follow up to check whether the benchmark study has led to improvements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Healthcare institutions are pressured by payers, patients and society to deliver high-quality care and have to strive for continuous improvement. Healthcare service provision is becoming more complex, leading to quality and performance challenges [1]. In addition, there is a call for transparency on relative performance between and within healthcare organizations [2]. This pushes providers to focus on performance and show the added value for customers/patients [3, 4].

Without objective data on the current situation and comparison with peers and best practices, organizations cannot determine whether their efforts are satisfactory or exceptional, and specifically, what needs improvement. Benchmarking is a common and effective method for measuring and analyzing performance. The Joint commission defines benchmarking as:

A systematic, data-driven process of continuous improvement that involves internally and/or externally comparing performance to identify, achieve, and sustain best practice. It requires measuring and evaluating data to establish a target performance level or benchmark to evaluate current performance and comparing these benchmarks or performance metrics with similar data compiled by other organizations, including best-practice facilities [5].

Benchmarking may improve hospital processes, though according to Van Lent et al. [6], benchmarking as a tool to improve quality in hospitals is not well described and possibly not well developed. Identifying meaningful measures that are able to capture the quality of care in its different dimensions remains a challenging aspiration [7].

Before embarking on an international project to develop and pilot a benchmarking tool for quality assessment of comprehensive cancer care (the BENCH-CAN project [8]) there was a need to establish the state of the art in this field, amongst others to avoid duplication of work. The BENCHCAN project [8] aims at benchmarking comprehensive cancer care and yield good practice examples at European Cancer Centers in order to contribute to improvement of multidisciplinary patient treatment. This international benchmark project included 8 pilot sites from three geographical regions in Europe (North-West (N = 2), South (N = 3), Central-East (N = 3). The benchmarking study was executed according to the 13 steps developed by van Lent et al. [6], these steps included amongst others the construction of a framework, the development of relevant and comparable indicators selected by the stakeholders and the measuring and analysing of the set of indicators. Accordingly, we wanted to obtain an overview on benchmarking of specialty hospitals and specialty care pathways. Schneider et al. [9] describe specialty hospitals as hospitals “that treat patients with specific medical conditions or those in need of specific medical or surgical procedures” (pp.531). These are standalone, single-specialty facilities.

The number of specialty hospitals is increasing [9]. Porter [10] suggests that specialization of hospitals improves performance; it results in a better process organization, improved patient satisfaction, increased cost-effectiveness and better outcomes. According to van Lent et al. [6] specialty hospitals represent a trend, however, the opinions about the added value are divided. More insight into the benchmarking process in specialty hospitals could be useful to study differences in organization and performance and the identification of optimal work procedures [6]. Although specialty hospitals may differ according to discipline they have similarities such as the focus on one disease category and the ambition to perform in sufficient volumes. The scope of the BENCH-CAN [8] project was on cancer centers and cancer pathways, however, we did not expect to find sufficient material on this specific categories and thus decided to focus on specialty hospitals in general. Against this background, we conducted a scoping review. A scoping review approach provides a methodology for determining the state of the evidence on a topic that is especially appropriate when investigating abstract, emerging, or diverse topics, and for exploring or mapping the literature [11] which is the goal of this study. This study had the following objectives: (i) provide an overview of research on benchmarking in specialty hospitals and care pathways, (ii) describe study characteristics such as method, setting, models/frameworks, and outcomes, (iii) verify the quality of benchmarking as a tool to improve quality in specialty hospitals and identify success factors.

Method

Scoping systematic review

There are different types of research reviews which vary in their ontological, epistemological, ideological, and theoretical stance, their research paradigm, and the issues that they aim to address [12]. Scoping reviews have been described as a process of mapping the existing literature or evidence base. Scoping studies differ from systematic reviews in that they provide a map or a snapshot of the existing literature without quality assessment or extensive data synthesis [12]. Scoping studies also differ from narrative reviews in that the scoping process requires analytical reinterpretation of the literature [11]. We used the framework as proposed by Arksey and O’Mally [13]. This framework consist of 6 steps: (i) identifying the research question, (iii) study selection, (iv) charting the data, (v) collating, summarizing and reporting the results, (vi) optional consultation. Step 6 (optional consultation) was ensured by asking stakeholders from the BENCH-CAN project for input. Scoping reviews are a valuable resource that can be of use to researchers, policy-makers and practitioners, reducing duplication of effort and guiding future research.

Data sources and search methods

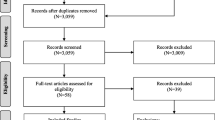

We performed searches in Pubmed and EMBASE. To identify the relevant literature, we focused on peer-reviewed articles published in international journals in English between 2003 and 2014. According to Saggese et al. [14] “this is standard practice in bibliometric studies, since these sources are considered ‘certified knowledge’ and enhance the results’ reliability” (pp.4). We conducted Boolean searches using truncated combinations of three groups of keywords and free text terms in title/abstract (see Fig. 1). The first consists of keywords concerning benchmarking and quality control. The second group includes key words regarding type of hospitals. All terms were combined with group 3: organization and administration. Different combinations of keywords led to different results, therefore five different searches in PubMed and four in EMBASE were performed. The full search strategies are presented in the Additional file 1. To retrieve other relevant publications, reference lists of the selected papers were used for snowballing. In addition stakeholders involved in the BENCH-CAN project [8] were asked to provide relevant literature.

Selection method/article inclusion and exclusion criteria

Using abstracts, we started by excluding all articles that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria, which covered topics not related to benchmarking and specialty hospitals. The two authors independently reviewed the remaining abstracts and made a selection using the following criteria: The article had to discuss a benchmarking exercise in a specialty hospital either in theory or in practice and/or the article had to discuss a benchmark evaluation or benchmark tool development. Only studies including organizational and process aspects were used, so studies purely benchmarking clinical indicators were excluded. At least some empirical material or theory (or theory development) on benchmarking methodology should be present; essays mainly describing the potential or added value of benchmarking without proving empirical evidence were thus excluded. The articles also had to appear in a peer-reviewed journal. The full texts were reviewed and processed by the first author. Only papers written in English were included.

Data extraction

General information was extracted in order to be able to provide an overview of research on benchmarking in specialty hospitals and care pathways. The following information was extracted from the included articles: first author and year of publication, aim, and area of practice. The analytical data were chosen according to our review objective. They included the following: (I) study design, (II) Benchmark model and/or identified steps, (III) type of indicators used, (IV) Study outcome, (V) The impact of the benchmarking project (measured by the identified improvements achieved through the benchmark or suggestions for improvements), and (VI) Success factors identified. The first author independently extracted the data and the second author checked 25% of the studies to determine inter-rater reliability.

Classification scheme benchmark models

At present, there is no standard methodology to classify benchmark models within healthcare in general and more specifically within specialty hospitals and care pathways. Therefore we looked at benchmark classification schemes outside the healthcare sector, especially in industry. A review of benchmarking literature showed that there are different types of benchmarking and a plethora of benchmarking process models [15]. One of these schemes was developed by Fong et al. [16] (Table 1). This scheme gives a clear description of each element included in the scheme and will therefore be used to classify the benchmark models described in this paper. It can be used to assess academic/research-based models. These models are developed mainly by academics and researchers mainly through their own research, knowledge and experience (this approach seems most used within the healthcare sector). This differs from Consultant/expert-based models (developed from personal opinion and judgment through experience in providing consultancy to organizations embarking on a benchmarking project) and Organization-based models (models developed or proposed by organizations based on their own experience and knowledge. They tend to be highly dissimilar, as each organization is different in terms of its business scope, market, products, process, etc.) [16].

Results

Review

The search strategy identified 1,817 articles. The first author applied the first review eligibility criteria, the topic identification (Fig. 1), to the titles and abstracts. After this initial examination 1,697 articles were excluded. Two authors independently reviewed the abstracts of 120 articles. Snowballing identified three new articles that were not already identified in the literature search. Sixty articles were potentially eligible for full text review. The full text of these 60 publications were reviewed by two authors, resulting in a selection of 24 publications that met all eligibility criteria (see Figs. 1 and 2).

Study characteristics

Table 2 provides an overview of the general information of the included articles. To assist in the analysis, articles were categorized into: pathway benchmarking, institutional benchmarking, benchmark evaluation/methodology and benchmarking using a patient registry (see Fig. 3). For each category the following aspects will be discussed: study design, benchmark model and/or identified steps, type of indicators used, Study outcome, impact of the benchmarking project (improvements/improvement suggestions) and success factors. The benchmark model and/or described steps will be classified using the model by Fong [16].

I Pathway benchmarking (PB)

A summary analysis of the pathway benchmarking studies can be found in Table 3.

PB Study design

Study design varied across the different pathway studies. Most studies (N = 7) [17,18,19,20,21,22] used multiple comparisons, from which five studies sought to develop indicators. Different methods were used for this indicator development such as a consensus method (Delphi) [17,18,19]. In other articles a less structured way of reaching consensus was used such as conference calls [20] and surveys [21]. One study used a prospective interventional design [14] while another study [23] used a retrospective comparative benchmark study with a mixed-method design. Setoguchi et al. [24] used a combination of prospective and retrospective designs. Existing literature was used in two studies [25, 26]. More information on study design can be found in Table 3.

PB Benchmark model

Eight articles described a benchmarking model and/or benchmarking steps. Applying the classification scheme by Fong et al. [16] most studies used benchmarking partners from the same industry (N = 6) [20,25,26,, 21, 24–27]. Two studies also used partners from the industry but on the global level. A total of 6 studies benchmarked performance [20,25,26,, 24–27], one study benchmarked performance and processes [18] and another study used strategic benchmarking [23]. All studies used benchmarking for collaborative purposes. For more information about the benchmark models see Table 3.

PB Indicators

Most of the pathway studies used outcome indicators (N = 7) [19,20,21,22, 24, 26, 27]. Hermann et al. [18] used a combination of process and outcome indicators e.g. case management and length of stay; and Chung et al. [17] used structure, process and outcome indicators. One study [20] used a mixture of process and outcome indicators, while another study [25] used a combination of structural and process indicators. Most studies used quantitative indicators, such as 5-year over-all survival rate [17]. Roberts et al. [28] describe the use of qualitative and quantitative indicators.

PB outcomes

Looking at the outcomes of the different pathway studies it can be seen that these cover a wide range of topics, Brucker [27] for example provided proof of concept for the feasibility of a nationwide system for benchmarking. The goal of establishing a nationwide network of certified breast centres in Germany can be considered largely achieved according to Wallwiener [25]. Wesselman [26] shows that most of the targets for indicators for colorectal care are being better met over the course of time.

Mainz et al. [19] reported a major difference between the Nordic countries with regard for 5 years survival for prostate cancer. However, they also reported difficulties such as: threats to comparability when comparing quality at the international level, this is mainly related to data collection. Stolar [22] showed that pediatric surgeons are unable to generate sufficient direct financial resources to support their employment and practice operational expenses. Outcomes of the other studies can be found in Table 3.

PB Impact

One article identified improvements in the diagnosis of the patient and provision of care related to participating in the benchmark for example improvements in the preoperative histology and radiotherapy after mastectomy [27]. Three articles identified suggestions for improvements based on the benchmark [20, 22, 24], in the provision of care for instance on the use of opiates at the end of life [17] and improvements on the organizational level such as the decrease of the frequency of hospital visits, lead times and costs [22]. For other improvements see Table 3.

PB Success factors

One study identified success factors. According to Brucker [27] a success factor within their project was the fact that participation was voluntary and all the data was handled anonymous.

II Institutional benchmarking (IB)

A summary analysis of the institutional benchmarking studies can be found in Table 4.

IB Study design

In the two articles by de Korne [3, 29] mixed methods were used to develop an evaluation frame for benchmarking studies in eye-hospitals. Barr et al.[30] used the National Practice Benchmark to collect data on Oncology Practice Trends. Brann [31] developed forums for benchmarking child and youth mental-health. Van Lent et al.[6] conducted three independent international benchmarking studies on operations management of comprehensive cancer centers and chemotherapy day units. Schwappach [32] used a pre–post design in two measurement cycles, before and after implementation of improvement activities at emergency departments. Shaw [33] used a questionnaire with 10 questions to collect data on pediatric emergency departments. More information on study design can be found in Table 4.

IB Benchmark model

Characterizing the benchmark models and/or steps with the scheme by Fong [16] it can be seen that all studies used partners from the industry, in two studies these partners were global. Two articles benchmarked performance [6, 29] while two other articles benchmarked both processes as performance [3, 32] and one article reported the benchmarking of performance and strategies [30]. More detailed information on the benchmark models can be found in Table 4.

IB Indicators

Most of the studies used outcome indicators (N = 6) [3,32,, 6, 29, 31–33]. Schwappach et al. [32] for example used indicators to evaluate speed and accuracy of patient assessment, and patients’ experiences with care by emergency departments. Van Lent [6] described the use of indicators that differentiated between the organizational divisions of cancer centers such as diagnostics, radiotherapy and research. Brann [31] used Key Performance Indicators such as 28-day readmissions to inpatient settings, and cost per 3-month community care period.

IB Outcomes

Different outcomes were mentioned in the study by de Korne [3] and on different aspects of operations management by van Lent [6]. However van Lent also showed that the results on the feasibility of benchmarking as a tool to improve hospital processes are mixed. The National Practice Benchmark (NPB) [30] demonstrated that the adaptation of oncology practices is moving toward gains in efficiency. Outcomes of the study by Schwappach [32] showed that improvements in the reports provided by patients were mainly demonstrated in structures of care provision and perceived humanity. Shaw [33] showed that benchmarking of staffing and performance indicators by directors yields important administrative data. Brann et al. [31] presented that benchmarking has the potential to illuminate intra- and inter-organizational performance.

IB Improvements

Improvements mentioned due to participating in the benchmark (Table 4) were a successful improvement project [6] leading to a 24% increase in bed utilization and a 12% increase in productivity in cancer centers and investments in Emergency Department (ED) structures, professional education and improvement of the organization of care [29].

IB Success factors

Almost all institutional benchmarking articles identified success factors (N = 7). Frequently mentioned factors were commitment of management [6, 31] and the development of good indicators [3, 6, 29].

III Benchmarking evaluation/methodology (BEM)

A summary analysis of the benchmarking evaluation/methodology studies can be found in Table 5.

BEM Study design

Ellershaw [34] assessed the usefulness of benchmarking using the Liverpool Care Pathway in acute hospitals in England with the use of a questionnaire. Ellis [35] performed a review of benchmarking literature. Matykiewicz [36] evaluated the Essence of Care as a benchmarking tool with a case study approach and qualitative methods.

Profit [37] used a review of the scientific literature on composite indicator development, health systems, and quality measurement in pediatric healthcare. More information on study design can be found in Table 5.

BEM Benchmark model/steps

Three studies describe a benchmark model. They all describe industry partners and process benchmarking (see Table 5).

BEM Indicators

One article described the use of indicators, though very minimally. Matykiewicz [36] describes benchmarking against best practice indicators, but specific indicators are not mentioned. Profit et al. [37] developed a model for the development of indicators of quality of care.

BEM Outcomes

The study by Ellershaw [34] displayed that almost three quarters of respondents in the hospital sector felt that participation in the benchmark had had a direct impact on the delivery of care. The outcomes of the study by Ellis [35] was that Essence of Care benchmarking is a sophisticated clinical practice benchmarking approach which needs to be accepted as an integral part of health service benchmarking activity. Matykiewicz [36] showed that whilst raising awareness is relatively straightforward, putting Essence of Care into practice is more difficult. Profit et al. [37] concluded that the framework they presented offers researchers an explicit path to composite indicator development.

BEM Improvements

Improvements due to the benchmark exercise that were identified included specific improvements in levels of communication between health professionals and relatives, within multidisciplinary teams and across sectors [34] and that through self-assessment against best practice problems could be identified and solved [36].

BEM Success factors

Three articles mentioned success factors, both Ellershaw [34] and Matykiewicz [36] mentioned the organization of a workshop, while Ellis [35] identified reciprocity as an important factor for success.

IV Benchmark using patient registry data

The only benchmark study [38] using patient registry data originated in oncology practice in the US (see Table 6). For this study National Cancer Database (NCDB) reports from the Electronic Quality Improvement Packet (e-QUIP) were reviewed ensuring all network facilities are in compliance with specific outcome benchmarks. Outcome indicators such as local adherence to standard-of-care guidelines were used. A review of the e-QUIP-breast study at Carolinas Medical Center (CMC) showed that treatment methods could be improved. No improvements were reported. At CMC, the registry has been a key instrument in program improvement in meeting standards in the care of breast and colon cancer by benchmarking against state and national registry data.

Discussion

There is a growing need for healthcare providers to focus on performance. Benchmarking is a common and supposedly effective method for measuring and analyzing performance [2]. Benchmarking in specialty hospitals developed from the quantitative measurement of performance to the qualitative measurement and achievement of best practice [39].

In order to inform the development of benchmark tool for comprehensive cancer care (the BENCH-CAN project) we assessed the study characteristics of benchmarking projects in specialty hospitals, avoid duplication and identified the success factors to benchmarking of specialty hospitals. This scoping review identified 24 papers that met the selection criteria which were allocated to one of four categories. Regarding our first two research objectives: (i) provide an overview of research on benchmarking in specialty hospitals and care pathways, (ii) describe study characteristics such as method, setting, models/frameworks, and outcomes, we reviewed the first three categories against a common set of five issues that shape the following discussion. The fourth category (Benchmark using patient registry data) had only a single paper so could not be appraised in the same way.

I Area of practice

In terms of study settings, we were interested in the areas where benchmarking would be most frequently used. Our review identified seven types of specialty hospitals. Most studies were set in oncology specialty hospitals. The majority (n = 12) of the articles described projects in which part of a specialty hospital or care pathway was benchmarked. This could be due to the fact that one of the success factors of a benchmarking project defined by van Lent et al. [6] is the development of a manageable-sized project scope. This can be an identified problem in a department or unit (part of a specialty hospital), or a small process that involves several departments (care pathway).

II Study design

Looking at the different study designs both quantitative as qualitative methods can be found. All institutional articles except Schwappach [29] (retrospective and prospective) made use of a prospective research design while most pathway articles used a retrospective multi-comparison design. Stakeholders often played an important role in the benchmarking process and consensus methods such as the Delphi method were frequently used to develop the benchmarking indicators.

III Benchmark model

Fifteen articles described a benchmark model/steps. All studies that described a benchmarking study made use of partners from the industry, in 4 articles these where from different countries, e.g. global. Most benchmarks were on performance (N = 8), others used a combination of performance and process benchmarking (N = 3) or performance and strategic benchmarking (N = 1). Three studies described a process benchmark and one benchmarking on strategies. The classification scheme was not developed for healthcare benchmarking specifically. This is shown by the definition of competitor. Some of the described partners in the benchmarking studies fit the first part of the definition: In business, a company in the same industry or a similar industry which offers a similar product or service [40] for example breast cancer centers or eye hospitals. However there is not always competition between these centers (second part definition). A healthcare specific scheme for benchmarking models would be preferred, this was however not found.

In some cases, a model has been uniquely developed–possibly using field expertise- for performing a particular type of benchmarking, which means that there was no evidence of the usability of the model beforehand. In their article on ‘Benchmarking the benchmarking models’ Anand and Kodali [15] however identify and recommend some common features of benchmarking models. Their cursory review of different benchmarking process models revealed that the most common steps are: “identify the benchmarking subject” and “identify benchmarking partners” [15]. The purpose of the benchmarking process models should be to describe the steps that should be carried out while performing benchmarking. Anand and Kodali [15] recommend that a benchmark model should be clear and basic, emphasizing logical planning and organization and establishing a protocol of behaviors and outcomes. Looking at the models described in this review it shows that only 5 articles describe models that have all the features described by Anand and Kodali [3, 6, 29, 32, 36].

IV Registry

The article about the use of a registry differed in the sense that no benchmark model or benchmarking steps were described. Instead it focused on the usefulness of using a registry for benchmarking. According to Greene et al. [38] a registry is a valuable tool for evaluating quality benchmarks in cancer care. Sousa et al. [41] showed the general demands for accountability, transparency and quality improvement make the wider development, implementation and use of national quality registries for benchmarking, inevitable. Based on this we had expected to find more articles describing the use of the registry for benchmarking, these were however not identified through our search.

V Indicators

Currently, it seems that the development of indicators for benchmarking is the main focus of most benchmarking studies. The importance of indicator development is highlighted by Groene et al. [42] who identified 11 national indicator development projects. Papers included in this study showed a wide array of approaches to define and select indicators to be used in the projects, such as interviews, focus groups, literature reviews and consensus surveys (Delphi method and others).

A review by Nolte [43] shows that there is an ongoing debate about the usefulness of process versus outcome indicators to evaluate healthcare quality. In most papers included in this study outcome indicators were used, especially in the pathway benchmarking papers. This seems contradictory to findings by Mant [44] who noted that the relevance of outcome measures is likely to increase towards macro-level assessments of quality, while at the organizational or team level, process measures will become more useful. Based on this one would expect the use of process indicators for especially the pathway articles.

Benchmarking as a tool for quality improvement and success factors

Regarding our third objective: “verify the quality of benchmarking as a tool to improve quality in specialty hospitals and identify success factors” we found the following. Only six articles described improvements related to the benchmark. Specific improvements were described in the level of communication between health professionals and relatives, within multidisciplinary teams and across sectors; service delivery and organization of care; and pathway development. Only three articles actually showed the improvement effects of doing a benchmark in practice. This could be linked to the fact that almost no benchmark model described a last step of evaluation of improvement plans as being part of the benchmark process. Brucker [27] showed that nationwide external benchmarking of breast cancer care is feasible and successful. Van Lent [6] however showed that the results on the feasibility of benchmarking as a tool to improved hospital processes were mixed. This makes it difficult to assess whether benchmarking is a useful tool for quality improvement in specialty hospitals.

Within the pathway studies only one paper mentioned success factors, in contrast with almost all institutional and benchmark evaluation- and methodology papers. Based on our review we’ve come up with a list of success factors for benchmarking specialty hospitals or care pathways (Table 7). One article exploring the benchmarking of Comprehensive Cancer Centres [6] produced a detailed list of success factors for benchmarking project (see Table 7), such as a well-defined and small project scope and partner selection based on clear criteria. This might be easier for specialty hospitals due to the specific focus and characteristics than for general hospitals. Organizing a meeting for participants, either before or after the audit visits, was mentioned as a success factor [34, 36]. Those workshops or forums provided the opportunity for participants to network with other organizations, discuss the meaning of data and share ideas for quality improvements and best practices. Especially the development of indicators was mentioned often, corresponding to our earlier observation about the emphasis that is put on this issue.

Although this scoping review shows that the included studies seem to focus on indicator development rather than the implementation and evaluation of benchmarking, the characteristics described (especially the models) can be used as a basis for future research. Researchers, policy makers or other actors that wish to develop benchmarking projects for specialty hospitals should learn lessons from previous projects to prevent the reinvention of the wheel. The studies in this review showed that ensuring the commitment to the project by the management team of hospitals participating and the allocation of sufficient resources for the completion of the project is paramount to the development of a benchmarking exercise. The information found in combination with the provided success factors may increase the chance that benchmarking results in improved performance in specialty hospitals like cancer centers in the future.

Limitations

A potential limitation is that by searching the titles and abstracts we may have missed relevant papers. The articles included in this review were not appraised for their scientific rigor, as scoping reviews do not typically include critical appraisals of the evidence. In deciding to summarize and report the overall findings without the scrutiny of a formal appraisal, we recognize that our results speak to the extent of the setting and model of the benchmark study rather than provide the reader with support for the effectiveness of benchmarking.

Conclusion

Benchmarking in specialty hospitals developed from simple data comparison to quantitative measurement of performance, qualitative measurement and achievement of best practice. Based on this review it seems however that benchmarking in specialty hospitals is still in development. Benchmarking seems to be most reported up on and possibly developed in the field of oncology and eye hospitals, however most studies do not describe a structured benchmarking method or a model that can be used repeatable. Based on our study we identified a list of success factors for benchmarking specialty hospitals. Developing ‘good’ indicators was mentioned frequently as a success factor. Within the included papers there seems to be a focus on indicator development rather than measuring performances, which is an indication of development rather than implementation. Further research is needed to ensure that benchmarking in specialty hospitals fulfills its objective, to improve the performance of healthcare facilities. Researchers wishing –as a next step- to evaluate the effectiveness of benchmarking to improve quality in specialty hospitals, should conduct evaluations using robust and structured designs, focusing on outcomes of the benchmark and preferably do a follow up to check whether improvement plans were implemented.

Abbreviations

- BC:

-

Breast cancer

- BEM:

-

Benchmarking evaluation/methodology

- CCC:

-

Comprehensive cancer center

- CMC:

-

Carolinas medical center

- DKG:

-

The German cancer society

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- e-QUIP:

-

Electronic quality improvement packet

- IB:

-

Institutional benchmarking

- KPI:

-

Key performance indicators

- N.A.:

-

Not applicable

- NCCN:

-

National comprehensive cancer network

- NCDB:

-

National cancer database

- NHS:

-

National health system

- NPB:

-

National practice Benchmark

- PB:

-

Pathway benchmarking

- PED:

-

Pediatric emergency department

- QI:

-

Quality indicator

- SMART:

-

Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, Relevant, Timely

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- USA:

-

United States of America

References

Plsek P, Greenhalgh T. Complexity science: The challenge of complexity in health care. BMJ. 2001;323:625.

Leape L, Berwick D, Clancy C, et al. Transforming healthcare: a safety imperative. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18:424–8.

De Korne D, Sol J, Van Wijngaarde J, Van Vliet EJ, Custers T, Cubbon M, et al. Evaluation of an international benchmarking initiative in nine eye hospitals. Health Care Manage R. 2010;35:23–35.

Campbell S, Braspenning J, Hutchinson A, et al. Research methods used in developing and applying quality indicators in primary care. BMJ. 2003;326:816–9.

oint Commission: Benchmarking in Health Care. Joint Commission Resources. 2011.

Van Lent W, De Beer R, Van Harten W. International benchmarking of specialty hospitals. A series of case studies on comprehensive cancer centres. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:253.

Pringle M, Wilson T, Grol R. Measuring “goodness” in individuals and healthcare systems. BMJ. 2002;325:704–7.

BenchCan http://www.oeci.eu/Benchcan (2013). Accessed 20 Feb 2015

Schneider JE, Miller TR, Ohsfeldt RL, Morrisey MA, Zelner BA, Li P. The Economics of Specialty Hospitals. Med Care Res Rev. 2008;65(5):531.

Porter ME, Teisberg EO. Redefining health care: creating value-based competition on results. Boston: Harvard Business School Press; 2006.

Constand MK, MacDermid JC, Dal Bello-Haas V, Law M. Scoping review of patient-centered care approaches in healthcare. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:271.

Levac D, Colquhoun H, O’Brien KK. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010;5:69.

Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a Methodological Framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. 2005;8:19–32.

Saggese S, Sarto F, Cuccurullo C. Evolution of the Debate on Control Enhancing Mechanisms: A Systematic Review and Bibliometric Analysis. IJMR. 2015;00:1–23.

Anand G, Kodali R. Benchmarking the benchmarking models. BIJ. 2008;15:257–91.

Fong SW, Cheng EWL, Ho DCK. Benchmarking: a general reading for management practitioners. Manage Decis. 1998;36:407–18.

Chung KP, Chang YJ, Lai MS, Nien-Chen Kuo R, Cheng SH, Chen LT, et al. Is quality of colorectal cancer care good enough? Core measures development and its application for comparing hospitals in Taiwan. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010;10:27.

Hermann R, Mattke S, Someth D, et al. Quality indicators for international benchmarking of mental health care. Int J Qual Health C. 2006;31–38.

Mainz J, Hjulsager M, Thorup Eriksen Og M, Burgaard J. National Benchmarking Between the Nordic Countries on the Quality of Care. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:505–7.

Miransky J. The Development of a Benchmarking System for a Cancer Patient Population. J Nurs Care Qual. 2003;18:38–42.

Stewart M, Wasserman R, Bloomfield C, Petersdorf S, Witherspoon RP, Appelbaum FR, et al. Benchmarks in Clinical Productivity: A National Comprehensive Cancer Network Survey. J Oncol Pract. 2007;3:2–8.

Stolar C, Alapan A, Torres S. University pediatric surgery: benchmarking performance. J Pediatr Surg. 2010;45:28–37.

Van Vliet E, Sermeus Q, Kop L, Kop LM, Sol JCA, Van Harten WH. Exploring the relation between process design and efficiency in high-volume cataract pathways from a lean thinking perspective. Int J Qual Health C. 2011;23:83–93.

Setoguchi S, Earle C, Glynn R, Stedman M, Polinski JM, Corcoran CP, et al. Comparison of Prospective and Retrospective Indicators of the Quality of End-of-Life Cancer Care. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:5671–8.

Wallwiener M, Brucker S, Wallwiener D. The Steering Committee: Multidisciplinary breast centres in Germany: a review and update of quality assurance through benchmarking and certification. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2012;285:1671–83.

Wesselman S, Winter A, Ferencz J, Seufferlein T, Post S. Documented quality of care in certified colorectal cancer centers in Germany: German Cancer Society benchmarking report for 2013. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2014;29:511–8.

Brucker S, Schumacher C, Sohn C, Rezai M, Bambergs M, Wallwiener D, et al. The Steering Committee: Benchmarking the quality of breast cancer care in a nationwide voluntary system: the first 5-year results (2003–2007) from Germany as a proof of concept. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:358.

Roberts D, Hurst K. Evaluating palliative care ward staffing using bed occupancy, patient dependency, staff activity, service quality and cost data. Palliat Med. 2012;27:123–30.

De Korne D, Van Wijngaarden J, Sol J, Betz R, Thomas RC, Schein OD, et al. Hospital benchmarking: Are U.S. eye hospitals ready? Health Care Manage Rev. 2012;37:187–98.

Barr T, Towle E. Oncology Practice Trends from the National Practice Benchmark. J Oncol Pract. 2012;8:292–7.

Brann P, Walter G, Coombs T. Benchmarking child and adolescent mental health organizations. Australas Psychiatry. 2011;19:125–32.

Schwappach D, Blaudszun A, Conen D, Ebner H, Eichler K, Hochreutener MA. ‘Emerge’: benchmarking of clinical performance and patients’ experiences with emergency care in Switzerland. Int J Qual Health C. 2003;15:473–85.

Shaw K, Ruddy R, Gorelick M. Pediatric emergency department directors’ benchmarking survey: Fiscal year 2001. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2003;19:143–7.

Ellershaw J, Gambles M, McGinchley T. Benchmarking: a useful tool for informing and improving care of the dying? Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:813–9.

Ellis J. All inclusive benchmarking. J Nurs Manag. 2006;14:377–83.

Matykiewicz L, Ashton D. Essence of Care benchmarking: putting it into practice. BIJ. 2005;12:467–81.

Profit J, Typpo K, Hysong S, Woodard LD, Kallen MA, Petersen LA. Improving benchmarking by using an explicit framework for the development of composite indicators: an example using pediatric quality of care. Implement Sci. 2010;5.

Greene F, Gilkerson S, Tedder P, Smith K. The Role of the Hospital Registry in Achieving Outcome Benchmarks in Cancer Care. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:497–9.

Zairi M, Leonard P. Practical Benchmarking. The Complete Guide. Londen: Chapman & Hall; 1994.

Business Dictionary: definition competitor. http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/competitor.html Accessed 16 June 2015.

Sousa P, Bazely M, Johansson S, Wijk H. The use of national registries data in three European countries in order to improve health care quality. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2006;19:551–60.

Groene O, Skau JKH, Frolich A. An international review of projects on hospital performance assessment. Int J Qual Health Care. 2008;20:162–71.

Nolte E. International benchmarking of healthcare quality; A review of the literature. Londen: RAND and London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; 2010.

Mant J. Process versus outcome indicators in the assessment of quality of health care. Int J Qual Health Care. 2001;13:475–80.

Acknowledgements

We thank Elda de Cuba for her help in designing the search strategies.

Funding

This study was funded by the European Commission Consumers, Health, Agriculture and Food Executive Agency through the BENCH-CAN project. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data-sets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and Additional file 1.

Authors’ contributions

AW designed and performed the literature search, analyzed and interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript. WvH participated in the analysis and interpretation of the data, and helped to draft the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Full search strategies PubMed and EMBASE (DOC 107 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wind, A., van Harten, W.H. Benchmarking specialty hospitals, a scoping review on theory and practice. BMC Health Serv Res 17, 245 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2154-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2154-y