Abstract

Background

Perceived interpersonal discrimination while seeking healthcare services is associated with poor physical and mental health. Yet, there is a paucity of research among Asian Americans or its subgroups.

This study examined the correlates of reported interpersonal discrimination when seeking health care among a large sample of Asian Indians, the 3rd largest Asian American subgroup in the US, and identify predictors of adverse self-rated physical health, a well-accepted measure of overall health status.

Methods

Cross-sectional survey. Participants comprised of 1824 Asian Indian adults in six states with higher concentration of Asian Indians.

Results

Mean age and years lived in the US was 45.7 ± 12.8 and 16.6 ± 11.1 years respectively. The majority of the respondents was male, immigrants, college graduates, and had access to care. Perceived interpersonal discrimination when seeking health care was reported by a relatively small proportion of the population (7.2 %). However, Asian Indians who reported poor self-rated health were approximately twice as likely to perceived discrimination when seeking care as compared to those in good or excellent health status (OR 1.88; 95 % CI 1.12–3.14). Poor self-rated health was associated with perceived health care discrimination after controlling for all of the respondent characteristics (OR 1.93; 95 % CI: 1.17–3.19). In addition, Asian Indians who lived for more than 10 years in the U.S. (OR 3.28; 95 % CI: 1.73–6.22) and had chronic illnesses (OR 1.39; 95 % CI: 1.17–1.64) (p < 0.05) were more likely to perceive discrimination when seeking health care. However, older Asian Indians, over the age of 55 years, were less likely to perceive discrimination than those aged 18–34 years Indian American.

Conclusion

Results offers initial support for the hypothesis that Asian Indians experience interpersonal discrimination when seeking health care services and that these experiences may be related to poor self-rated health status.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Perceived interpersonal discrimination, a hypothesized psychosocial stressor based on the perception on poor or unfair treatment when compared to others, is strongly associated with poor overall physical and mental health among racial/ethnic minority groups [1], and Whites [2]. Evidence from recent literature reviews [3, 4] and meta-analysis [5] suggest that perceived interpersonal discrimination is associated with a myriad of health behaviors and outcomes among various of racial/ethnic minority groups and even among select groups of Whites [6]. Specifically, health outcomes associated with perceived interpersonal discrimination have varied widely from alcohol/tobacco use, [7–11] hypertension/blood pressure, [12–15] mental health, [16–19] excess weight/obesity, [20–22] and infant mortality [23, 24].

Furthermore, research has shown that perceived discrimination, while seeking healthcare services, has robust links to chronic health conditions (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension) and poor mental health outcomes (e.g., depression and psychiatric disorders). In particular, studies have suggested that perceived discrimination when seeking health care services is related to important care process factors such as health care utilization [2, 25, 26], communication between patient and provider [27, 28] and treatment adherence [29]. The Institute of Medicine’s report- Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Healthcare - acknowledged that medical provider’s bias/prejudice is one mechanism for poor quality care and health outcomes among racial/ethnic minorities [30]. Yet, the study of discrimination in the healthcare setting is still in its infancy [5, 31]. The majority of the studies have examined the experiences of African Americans/Blacks and Hispanics [1]. There is a paucity of research on Asians as a whole or its specific groups [32], despite the fact that Asian Americans are one of the fastest growing populations in the United States [31].

Asian Indians (AIs) are the third largest Asian sub-group in the U.S., after Chinese and Filipinos, and one of the fastest growing ethnic minority group [33]. According to the 2010 Census, the U.S. is home to 3.2 million Asian Indians who are not confined to specific geographic areas in the US. In fact, Asian Indian were the largest detailed Asian subgroup in 23 states, more than any other detailed Asian group in 2010 [33]. Contrary to the model minority myth prevalent three decades earlier, Asian Indians have high prevalence rates of coronary heart disease (CHD), diabetes, and metabolic syndrome [34] and diverse linguistic, educational, religious and socio-economic characteristics [35, 36]. Despite their growing numbers and the reported high prevalence of chronic diseases, we are not aware of any research has explored perceived discrimination in medical care utilization in this high-risk ethnic group. In addition, prior studies on perceived discrimination among Asian immigrants have been narrow in scope or have aggregated multiple ethnic groups into the general category of “Asian Americans” [9, 37–39].

The lack of epidemiological data on health outcomes and perceived discrimination when seeking healthcare services among Asian Indians makes this study timely. Discrimination is a social stressor and physical health outcomes linked to discrimination may result in physiological responses such as elevated blood pressure and heart rate, which over time advance into chronic diseases such as CHD and hypertension [40].

The objectives of this study were to examine correlates of reported discrimination when seeking health care among a large sample of immigrant Asian Indian adults and to identify predictors of adverse self-rated physical health, a well-accepted measure of overall health status among individuals [41].

Methods

Participants and data collection

The data for this study were derived from the Diabetes among Indian Americans (DIA) study, the first national epidemiological survey of Asian Indians in the United States. A total of 1824 Asian Indians, aged 18 years and older, were interviewed from seven US cities with high concentration of Asian Indians - Houston, TX; Phoenix, AZ; Washington, DC; Boston, MA; San Diego, CA; Edison, NJ and Parsippany, NJ. The sampling procedure has been described in a prior publication [42]. Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to participation. Telephone interviews were conducted by trained multilingual interviewers. The overall response rate was 37 % with 1824 Asian Indians completing the phone interview. Asian Indians that declined to participate in the study were requested to respond to a short questionnaire. Non-participants did not differ in gender, educational level, family history of diabetes and CVD or smoking status, but were significantly older than participants. The overall response rate was higher than in published health surveys of Asians or Asian Indians [43–46]. Additional information about the sampling frame and data collection for this study is available from a previous published study [34]. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Texas A&M University.

Measures

Independent and outcome variables

Two primary variables of interest were assessed in our study, perceived discrimination when seeking health care and self-reported health status. Perceived discrimination when seeking health care, derived from questions from the Commonwealth Fund Health Quality Survey [47], was assessed by the following question: “Thinking of your experiences with receiving health care in the past 12 months, have you felt uncomfortable or been treated badly by your health care provider?” The responses were “Yes” “No” and “Unsure”. We created a binary variable where the “yes” responses were recoded as 1, and the “no” responses were recoded as 0. The “unsure” responses were excluded from the analyses because it does not unambiguously indicate the presence or absence of perceived discrimination; only 2 % (n = 32) of the sample indicated they were unsure. The second outcome in the study used the traditional self-rated health question: “Compared to others your age, how would you rate your overall physical health” with response options of “excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor” [48]. We created a binary variable by recoding “excellent/very good/good” as 0 and “fair/poor” as 1. Some of these questions have been used in publications from the DIA study [34, 42].

Covariates

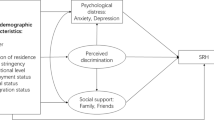

Based on the existing literature, we included several covariates in our analyses [2, 5, 32, 49, 50]. Socio-demographic correlates included sex, age (18–34, 35–44, 45–54, ≥ 55 years), annual household income (< $24,999, $25,000–74,999, $75,000–$99,999, ≥$100,000), education (< high school graduate, some college or college graduate, graduate/professional), marital status (currently married, formerly married, never married). Additionally, we also included several health related correlates including health insurance (yes versus no), body mass index (Underweight/ normal: <24.9 kg/m2, Overweight: 25.00–29.9 kg//m2, Obese: ≥ 30 kg/m2), current cigarette and tobacco product use (yes versus no) and a count variable for sex-specific health conditions that included conditions of high blood cholesterol, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, high blood pressure, depression, arthritis, osteoporosis, kidney problems, thyroid problems, back problems (with a range of 0–9). Acculturation factors were included in the analysis since research shows acculturative stress can play a critical role in health among minorities; the two proxy acculturation measures were residency in the U.S. (<10 years vs. ≥ 10 years) and English language proficiency (speaks English very/pretty well versus not too well/not at all).

Statistical analyses

After accounting for missing data across the variables used in the study, 892 respondents had no missing data for all of the study variables. As such, we further evaluated the item non-response for each of the variables with respect to the other variables. Compared to those with complete non-missing data (n = 892), independent t-test and chi-square analyses confirmed respondents with missing data (n = 932) did not significantly differ with regards to either outcome variable. However, there were some differences with respect to some of the covariates. Specifically, those respondents who were not missing on any of the variables were more likely (p < 0.05) to be male, live in a higher income household, have more education, speak English well, have health insurance and to be a current tobacco user when compared to the respondents who had a missing response on one or more of the variables. No differences (p > 0.05) however were noted between the two groups with respect to age, marital status, BMI or years lived in the US. Although we suspected that the data may have been missing at random, [51] we chose to impute data for missing cases using an iterative imputation method that imputed multiple variables by using chained equations, a sequence of univariate imputation methods with fully conditional specification of prediction equations [52, 53]. For the final post-imputation analyses, we used 10 imputed datasets of 1824 respondents in each datasets. All of the analyses in this study used STATA’s multiple (mi) estimation commands, which adjusted the coefficients and standard errors for the variability between the 10 imputed datasets according to the combination rules proposed by Rubin [54].

Respondent characteristics were summarized and are presented in Table 1. Following the analytic plan used in a similar study [2], we conducted bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses to examine the reports of perceived discrimination when seeking health care (Table 2) and poor self-rated health (Table 3). The bivariate analyses examined the relationship between perceived discrimination (Table 2) and each of the respondent’s characteristics separately. The multivariable logistic regression models assessed the adjusted odds ratios of reporting perceived discrimination (Table 2) and poor self-rated health (Table 3). All analyses were performed using the STATA software v13.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

The sample was comprised of Asian Indian men and women between 18 and 88 years of old (n = 1824). The sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. A small proportion of participants (approximately 7 %) reported perceived discrimination when seeking health care and 14 % reported poor (fair or poor) self-rated health. The majority of participants were males (60 %), 45 years of age and older (50 %), (higher socioeconomic status with reported annual household income of more than $77,000 (~50 %), had a college degree or a higher (90 %), and were married (90 %).

In terms of acculturation status, approximately two-thirds of the sample lived in the US for more than 10 years and 90 % reported speaking English very well or pretty well. Given the relatively high socioeconomic status, it is not surprising that approximately 85 % of the sample reported having health insurance. The majority of the sample reported no tobacco use (93.7 %) and, on average, had only one chronic illness (1.03 ± 0.03). Although the prevalence of obesity was not as high as the general U.S. population, almost one in every three respondents were overweight based on their BMI.

Results from the bivariate and multivariable logistic regression analyses are presented in Table 2. Although perceived discrimination when seeking health care were reported by a relatively small proportion of the population (7.2 %), the patterns of report was very instructive with respect to some of the covariates. For example, reports of discrimination were associated with age, self-rated health, acculturation and presence of chronic illnesses. The results between the unadjusted and adjusted ORs were consistent, with the exception of age; age was statistically significant in the adjusted models but not in the unadjusted models. As shown in the adjusted model, respondents who reported fair/poor health were more likely to report experiencing discrimination when seeking healthcare services. Specifically, respondents who reported fair/poor self-rated health were approximately twice as likely to perceived discrimination when seeking care as compared to those in good or excellent health status (OR 1.88; 95 % CI 1.12–3.14). Furthermore, Asian Indians who lived for more than 10 years in the U.S. (OR 3.28; 95 % CI: 1.73–6.22) and had chronic illnesses (OR 1.39; 95 % CI: 1.17–1.64) (p < 0.05) were more likely to perceive discrimination when seeking health care. However, older Asian Indians were less likely to perceive discrimination than those aged 18–34 years.

The relationships of self-rated health status, perceived discrimination when seeking health care and the respondent characteristics are presented in Table 3. Poor self-rated health was associated with perceived health care discrimination after controlling for all of the respondent characteristics in the model (OR 1.93; 95 % CI: 1.17–3.19). Additional respondent characteristics that were positively associated with poor self-rated health included younger age (18–34 years old compared to >54 years old), low household income (< $25,000 compared to $25,000–$74,999), having no health insurance, being obese, current use of tobacco products, and having one or more chronic illness. Much like the results from the analyses of perceived discrimination when seeking health care (Table 2), the odds ratios between unadjusted and adjusted analysis remained relatively consistent in magnitude with the exception of age. In the unadjusted model, although the coefficients were not statistically significant (p < 0.05), older Asian Indians were more likely to report poor health as compared to those aged 18–34 years. However, after adjusting for all the demographic characteristics, the coefficients reversed directions. In particular, older Asian Indians, over the age of 55 years, were less likely (OR 0.48; 95 % CI: 0.26–0.89) to report being in poor health than their younger counterparts (18–34 years old).

Discussion

The results of this study contributes to a growing body of evidence which suggests that Asian Indians, similar to other racial/ethnic minority groups in the U.S., experience discrimination while seeking health care services [5, 15]. Although the reports of perceived discrimination when seeking health care services were relatively low (7.2 %) in this population, compared to other racial/ethnic minorities in the US, [1] it is similar to findings by Southeast Asians (7.5 %) and Pacific Islanders (3.0–9.1 %) as reported in previous studies [25, 26, 55–57]. In our sample, reports of health care discrimination ranged from 3.5 % among those with less than a college degree to 13.3 % among those with fair/poor self-rated health status. Similar to other studies, results from the multivariable analyses suggest that Asian Indians who reported fair or poor health were more likely to report discrimination when seeking health care services, adjusting for various confounders in the model [2, 26, 58].

Results also suggested that personal characteristics such as age, length of residency in the US and chronic illness were all predictors of perceived discrimination. For example, age was inversely associated with reports of discrimination while seeking health care [2], which is relatively consistent with other studies of non-healthcare discrimination [5]. Prior studies suggest that older individuals who grew up in the oppressive civil rights era are less likely to perceived discrimination in today’s society in light of the current civil rights enjoyed by racial/ethnic minorities today [32, 49 50]. An alternate explanation is that older Asian Indians may have been exposed to greater unfair events and have developed adequate coping skills to deal with the effects of discrimination. Having coping skills appears to reduce the effects of discrimination and resiliance among minorities [59]. This cultural resilience is often fostered by protective factors of new experiences, opportunities and cultural connectedness with ethnic community networks to neutralize or offset the detrimental effect of discrimination to reduce stress [60]. Hence, cultural resilience has been regarded as a potentially positive resource for compensating the detrimental effect of stress and social risk factors to reduce discrimination and improve social outcomes. Furthermore, cultural resiliance is positively associated with better mental health status even among forced migrants [61]. It is also possible that younger Asian Indians, who tend to be new immigrants, may be more susceptible to discrimination sensitization due to a greater psychological distress for acculturation to the American culture, occupational issues, or group identification. Acculturation, a complex phenomeon, is defined as the extent to which immigrants adapt to the host culture in comparison to retaining their ethnic culture [62]. The degree of acculturation and time spent in the United States among immigrant AIs can play a significant factor in the psychological distress [63] and are associated with self-reported experiences of racial discrimination especially among acculturated individuals [63]. While health of foreign-born individuals are reported to be better than native-borns in the US [64], the healthy immigrant effect slowly wanes with convergence of health to native-borns with length of residency; structural and contextual factors such as social and economic inequalities also influence the perception of discrimination and shape health status [65]. New immigrants are less likely to interact with the health systems of their host countries then native-borns but with increasing length of stay there is a narrowing the utilization of health services [64].

Past research has revealed that social support, coping style, and ethnic identity moderate the link between perceived discrimination and health [5]. If indeed, younger Asian Indians percieved greater discrimination in the health care system, this is particularly troubling if such perceptions eventually leads to the under-ulilization of health sercives. Studies on Southeast Asians in the United States have found that forbearance or emotion-focused coping diminished discrimination-related depression [19]. However, efficacy of emotion-focused coping for Asian Indians my be lessened when younger individuals adapt to the Western environment [66]. Similarly, Asian Indians who have lived in the United States for more than 10 years were more than three times as likely to percieved health care discrimination when compared to those who were in the US for less than 10 years, supporting the notion that discrimination may be positively associated with length of time lived in the US among other Asian subgroups in the US [67]. Future research should focus on the potential consequences of percieved discrimination in the health care settings, such as adherence and untilization.

Our results also highlighted that experiences of health care discrimination are associated with fair or poor self-rated health status. Asian Indians who perceived discrimination were twice as likely (OR 1.93; 95 % CI: 1.17–3.19) to report fair or poor health status as compared to those that did not report any discrimination, controlling for important demographic characteristics. Although Asian Indian women were not significantly more likely to report fair or poor self-rated health, prior studies indicated Asian American women reported slightly higher rates of fair to poor-self rated health status than men [68]. Perceived health care discrimination increased the odds of chronic illness and corroborates with population-based health studies [31, 38, 69]. Stronger associations are consistently found for mental health than physical health outcomes suggesting a higher discrimination threshold may be needed for physical health effects [70].

The findings of the present study should be considered in the context of several limitations. First, this study used cross-sectional data; therefore, our understanding of the causal relationship we examined is limited. Second, the data used are from select large cities in the US. Although the study employed a sampling procedure to recruit a large sample of Asian Indians, future research is needed to determine whether our findings are generalizable to the larger population of Asian Indians in the US. Finally, we were not able to ascertain the perceived reasons for the poor treatment (e.g. race/ethnicity, age, etc.) due to the relatively small proportion indicating that they were treated unfairly. Hence, further research is necessary to examine this particular question among this fastest growing subgroup of Asians in the U.S.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study offers initial support for the hypothesis that Asian Indians experience discrimination when seeking health care services and that these experiences may be related to poor self-rated health status. Although Asians in general and Asian Indians in particular have higher levels of education and income, they may not be perceived as having vulnerability to the experiences of discrimination in healthcare settings. As noted, additional studies that explore the role of perceived interpersonal discrimination in medical care utilization among Asian Indians in the US is warranted. This particular line of inquiry should continue to be of interest because Asian Indians are the third largest sub-group of Asians in the US. Indeed, if perceived interpersonal discrimination when seeking healthcare services impacts future healthcare utilization, this may exacerbate the overall health burden of the Asian Indian population in the US given that chronic health conditions are relatively high among this ethnic group despite their relatively high socioeconomic status. This study also highlights the need to include Asian Indians in future research that examines the impact of health care utilization policies, like cultural competency training among healthcare employees.

Additionally, future research should also examine the dimension and type of discrimination as well as protective factors that can moderate between discrimination and physical and mental health outcomes. This will refine our knowledge base and guide policies and strategies, while acknowledging the heterogeneity within Asians and Asian Indians in order to reduce health disparities in this fastest growing subgroup of Asians in the U.S.

References

Shavers VL, Fagan P, Jones D, Klein WMP, Boyington J, Moten C, Rorie E. The state of research on racial/ethnic discrimination in the receipt of health care. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(5):953–66.

Hausmann LRM, Jeong K, Bost JE, Ibrahim SA. Perceived discrimination in health care and health status in a racially diverse sample. Med Care. 2008;46(9):905–14.

Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–8.

Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47.

Pascoe EA, Smart Richman L. Perceived discrimination and health: a meta-analytic review. Psychol Bull. 2009;135(4):531–54.

Hunte HE, Williams DR. The association between perceived discrimination and obesity in a population-based multiracial and multiethnic adult sample. Am J Public Health. 2009;99(7):1285–92.

Bennett GG, Wolin KY, Robinson EL, Fowler S, Edwards CL. Perceived racial/ethnic harassment and tobacco use among African American young adults. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(2):238–40.

Borrell LN, Jacobs Jr DR, Williams DR, Pletcher MJ, Houston TK, Kiefe CI. Self-reported racial discrimination and substance use in the coronary artery risk development in adults study. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:1068–79.

Chae DH, Takeuchi DT, Barbeau EM, Bennett GG, Lindsey J, Krieger N. Unfair treatment, racial/ethnic discrimination, ethnic identification, and smoking among Asian Americans in the National Latino and Asian American study. Am J Public Health. 2008;983(3):485–92.

Guthrie BJ, Young AM, Williams DR, Boyd CJ, Kintner EK. African American girls’ smoking habits and day-to-day experiences with racial discrimination. Nurs Res. 2002;51(3):183–90.

Hunte HER, Barry AE. Perceived discrimination and DSM-IV–based alcohol and illicit drug use disorders. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(12):e111–7.

Matthews KA, Salomon K, Kenyon K, Zhou F. Unfair treatment, discrimination, and ambulatory blood pressure in black and white adolescents. Health Psychol. 2005;24(3):258–65.

Krieger N, Sidney S. Racial discrimination and blood pressure: the CARDIA study of young black and white adults. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(10):1370–8.

Lewis TT, Barnes LL, Bienias JL, Lackland DT, Evans DA, Mendes de Leon CF. Perceived discrimination and blood pressure in older African American and white adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64A(9):1002–8.

Ryan AM, Gee GC, Laflamme DF. The Association between self-reported discrimination, physical health and blood pressure: findings from African Americans, Black immigrants, and Latino immigrants in New Hampshire. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2006;17(2 Suppl):116–32.

Canady RB, Bullen BL, Holzman C, Broman C, Tian Y. Discrimination and symptoms of depression in pregnancy among African American and White women. Womens Health Issues. 2008;18(4):292–300.

Chae DH, Lee S, Lincoln KD, Ihara ES. Discrimination, family relationships, and major depression among Asian Americans. J Immigr Minor Health. 2012;14(3):361–70.

Hunte HE, King K, Hicken M, Lee H, Lewis TT: Interpersonal discrimination and depressive symptomatology: examination of several personality-related characteristics as potential confounders in a racial/ethnic heterogeneous adult sample. BMC Public Health 2013, 13:1084.

Noh S, Beiser M, Kaspar V, Hou F, Rummens J: Perceived racial discrimination, depression, and coping: a study of Southeast Asian refugees in Canada. Journal of health and social behavior 1999, 40(3):193-207.

Hansson L, Rasmussen F. Perceived health care discrimination is associated with weight gain among severely obese women. Int J Behav Med. 2010;17:304.

Parker LJ, Hunte HE. Examining the relationship between the endorsement of racial/ethnic stereotypes and excess body fat composition in a national sample of African Americans and black Caribbeans. Ethn Dis. 2013;23(4):462–8.

Cozier YC, Wise LA, Palmer JR, Rosenberg L. Perceived racism in relation to weight change in the black women’s health study. Ann Epidemiol. 2009;19:379–87.

David RJ, Collins Jr JW. Bad outcomes in black babies: race or racism? Ethn Dis. 1991;1(3):236–44.

Mustillo SK. Discrimination as a psychosocial determinant of the Black/White difference in maternal health, preterm delivery, and low birth weight: the cardia study. Durham: ProQuest Information & Learning; 2002.

Burgess DJ, Ding Y, Hargreaves M, van Ryn M, Phelan S. The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19(3):894–911.

Lee C, Ayers SL, Kronenfeld JJ. The association between perceived provider discrimination, healthcare utilization and health status in racial and ethnic minorities. Ethn Dis. 2009;19(3):330–7.

Brondolo E, Hausmann LRM, Jhalani J, Pencille M, Atencio-Bacayon J, Kumar A, Kwok J, Ullah J, Roth A, Chen D, et al. Dimensions of perceived racism and self-reported health: examination of racial/ethnic differences and potential mediators. Ann Behav Med. 2011;42(1):14–28.

Perez D, Sribney WM, Rodríguez MA. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24 Suppl 3:548.

Bogart LM, Wagner GJ, Galvan FH, Klein DJ. Longitudinal relationships between antiretroviral treatment adherence and discrimination due to HIV-serostatus, race, and sexual orientation among African-American men with HIV. Ann Behav Med. 2010;40(2):184–90.

Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, Institute of Medicine. Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health C. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2003.

Hahm HC, Ozonoff A, Gaumond J, Sue S. Perceived discrimination and health outcomes a gender comparison among Asian-Americans nationwide. Women's health issues : official publication of the Jacobs Institute of Women's Health 2010, 20(5):350-58.

Gee GC, Ro A, Shariff-Marco S, Chae D: Racial discrimination and health among Asian Americans: evidence, assessment, and directions for future research. Epidemiol Rev 2009, 31:130-51.

Hoeffel EM, Rastogi S, Kim MO, Shahid H: The Asian Population: 2010. In. Edited by Bureau USC; 2012.

Misra R, Patel T, Kotha P, Raji A, Ganda O, Banerji M, Shah V, Vijay K, Mudaliar S, Iyer D et al: Prevalence of diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular risk factors in US Asian Indians: results from a national study. J Diabetes Complications 2010, 24(3):145-53.

Gupta R: Predictors of health among Indians in United States. In. Dallas TX: India Association of North texas; 2004.

Rangaswamy P: Asian Indians in Chicago: Growth and Change in a model Minority. Chicago: Eerdmans publishing Company; 1996.

Duldulao AA, Takeuchi DT, Hong S: Correlates of suicidal behaviors among Asian Americans. Archives of suicide research : official journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research 2009, 13(3):277-90.

Gee GC, Delva J, Takeuchi DT: Relationships between self-reported unfair treatment and prescription medication use, illicit drug use, and alcohol dependence among Filipino Americans. American journal of public health 2007, 97(5):933-40.

Hahn EA, Du H, Garcia SF, Choi SW, Lai JS, Victorson D, Cella D: Literacy-fair measurement of health-related quality of life will facilitate comparative effectiveness research in Spanish-speaking cancer outpatients. Medical care 2010, 48(6 Suppl):S75-82.

Mays VM, Cochran SD, Barnes NW: Race, race-based discrimination, and health outcomes among African Americans. Annual review of psychology 2007, 58:201-25.

Kaplan GA, Camacho T: Perceived health and mortality: a nine-year follow-up of the human population laboratory cohort. Am J Epidemiol 1983, 117(3):292-304.

Misra R, Balagopal P, Klatt M, Geraghty M: Complementary and alternative medicine use among Asian Indians in the United States: a national study. Journal of alternative and complementary medicine 2010, 16(8):843-52.

Yagalla MV, Hoerr SL, Song WO, Enas E, Garg A: Relationship of diet, abdominal obesity, and physical activity to plasma lipoprotein levels in Asian Indian physicians residing in the United States. J Am Diet Assoc 1996, 96(3):257-61.

Misra R, Patel TG, Davies D, Russo T: Health promotion behaviors of Gujurati Asian Indian immigrants in the United States. J Immigr Health 2000, 2(4):223-30.

Lien P. Pilot National Asian American Political Survey (PNAAPS), 2000–2001. In: Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR) [distributor]. 2004.

Misra R, Vadaparampil ST. Personal cancer prevention and screening practices among Asian Indian physicians in the United States. Cancer Detect Prev. 2004;28(4):269–76.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Telfair J, Sorkin D. Cultural competency and quality of care: obtaining the patient’s perspective. In: Commonwealth fund report. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2006.

Eriksson I, Unden AL, Elofsson S. Self-rated health. Comparisons between three different measures. Results from a population study. Int J Epidemiol. 2001;30(2):326–33.

Samson F. Race and the limits of american democracy: African Americans from the fall of reconstruction to the rise of the Ghetto. In: The Oxford handbook of African American citizenship, 1865-Present. Cary: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):208–30.

Buhi ER, Goodson P, Neilands TB. Out of sight, not out of mind: strategies for handling missing data. Am J Health Behav. 2008;32(1):83–92.

StataCorp. Multiple-imputation reference manual. College Station: Stata Press; 2011.

White IR, Royston P, Wood AM. Multiple imputation using chained equations: issues and guidance for practice. Stat Med. 2011;30(4):377–99.

Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. New York: Wiley; 1987.

Lyles CR, Karter AJ, Young BA, Spigner C, Grembowski D, Schillinger D, Adler NE. Correlates of patient-reported racial/ethnic health care discrimination in the Diabetes Study of Northern California (DISTANCE). J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22(1):211–25.

Sorkin DH, Ngo-Metzger Q, De Alba I. Racial/ethnic discrimination in health care: impact on perceived quality of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(5):390–6.

Yoo HC, Gee GC, Takeuchi D. Discrimination and health among Asian American immigrants: disentangling racial from language discrimination. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68(4):726–32.

D’Anna LH, Ponce NA, Siegel JM. Racial and ethnic health disparities: evidence of discrimination’s effects across the SEP spectrum. Ethn Health. 2010;15(2):121–43.

James KLC, Khoo G. Social identity correlates of minority workers’ health. Acad Manag J. 1994;37:383–96.

Spence ND, Wells S, Graham K, George J. Racial discrimination, cultural resilience, and stress. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61(5):298–307.

Siriwardhana C, Ali SS, Roberts B, Stewart R. A systematic review of resilience and mental health outcomes of conflict-driven adult forced migrants. Confl Heal. 2014;8:13.

Venkatesh S, Weatherspoon LJ, Kaplowitz SA, Song WO. Acculturation and glycemic control of Asian Indian adults with type 2 diabetes. J Community Health. 2013;38(1):78–85.

Krieger N, Kosheleva A, Waterman PD, Chen JT, Koenen K. Racial discrimination, psychological distress, and self-rated health among US-born and foreign-born Black Americans. Am J Public Health. 2011;101(9):1704–13.

McDonald JT, Kennedy S. Insights into the ‘healthy immigrant effect’: health status and health service use of immigrants to Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59(8):1613–27.

Viruell-Fuentes EA. Beyond acculturation: immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2007;65(7):1524–35.

Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):232–8.

Gee GC, Ro A, Gavin A, Takeuchi DT. Disentangling the effects of racial and weight discrimination on body mass index and obesity among Asian Americans. Am J Public Health. 2008;98(3):493–500.

(NHIS) NHIS. National Center for Health Statistics. Health Data Ineractive. 2007 edn; 2007.

Gee GC, Ryan A, Laflamme DJ, Holt J. Self-reported discrimination and mental health status among African descendants, Mexican Americans, and other Latinos in the New Hampshire REACH 2010 Initiative: the added dimension of immigration. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(10):1821–8.

Gee GC. A multilevel analysis of the relationship between institutional and individual racial discrimination and health status. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(4):615–23.

Acknowledgements

Not Applicable.

Funding

The DIA study was funded by the American Association of Physicians of Indian Origin (AAPI) USA.

Availability of data and material

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. The DIA dataset is currently not deposited in any publicly available repositories. The authors do not wish to share their data in such repositories because of the unique nature of this only large scale population-level data on immigrant Asian Indians in the US. However, the authors are willing to provide additional supporting files (in STATA) on which the conclusions of the manuscript have been based.

Authors’ contributions

RM supervised the project and drafted/edited the manuscript; HH completed the literature review, carried out the data analysis, and drafted/ edited the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Participation was voluntary, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects prior to participation. The study was approved by the institutional review board of Texas A&M University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Misra, R., Hunte, H. Perceived discrimination and health outcomes among Asian Indians in the United States. BMC Health Serv Res 16, 567 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1821-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-016-1821-8