Abstract

Background

Decision aids educate patients about treatment options and outcomes. Communication aids include question lists, consultation summaries, and audio-recordings. In efficacy studies, decision aids increased patient knowledge, while communication aids increased patient question-asking and information recall. Starting in 2004, we trained successive cohorts of post-baccalaureate, pre-medical interns to coach patients in the use of decision and communication aids at our university-based breast cancer clinic.

Methods

From July 2005 through June 2012, we used the RE-AIM framework to measure Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation and Maintenance of our interventions.

Results

-

1.

Reach: Over the study period, our program sent a total of 5,153 decision aids and directly administered 2,004 communication aids. In the most recent program year (2012), out of 1,524 eligible patient appointments, we successfully contacted 1,212 (80 %); coached 1,110 (73 %) in the self-administered use of decision and communication aids; sent 958 (63 %) decision aids; and directly administered communication aids for 419 (27 %) patients. In a 2010 survey, coached patients reported self-administering one or more communication aids in 81 % of visits

-

2.

Effectiveness: In our pre-post comparisons, decision aids were associated with increased patient knowledge and decreased decisional conflict. Communication aids were associated with increased self-efficacy and number of questions; and with high ratings of patient preparedness and satisfaction

-

3.

Adoption: Among visitors sent decision aids, 82 % of survey respondents reviewed some or all; among those administered communication aids, 86 % reviewed one or more after the visit

-

4.

Implementation: Through continuous quality adaptations, we increased the proportion of available staff time used for patient support (i.e. exploitation of workforce capacity) from 29 % in 2005 to 84 % in 2012

-

5.

Maintenance: The main barrier to sustainability was the cost of paid intern labor. We addressed this by testing a service learning model in which student interns work as program coaches in exchange for academic credit rather than salary. The feasibility test succeeded, and we are now expanding the use of unpaid interns.

Conclusion

We have sustained a clinic-wide implementation of decision and communication aids through a novel staffing model that uses paid and unpaid student interns as coaches.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Approximately 230,000 women every year are diagnosed with breast cancer in the United States [1]. Participating in breast cancer treatment decisions is often difficult for patients because the diagnosis is a shock and throws many patients into cognitive and emotional overload. Patient participation in decision making is important though, because common treatments (surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, hormone therapy) differ in impact on survival, recurrence, and quality of life. A needs assessment found that breast cancer patients are exposed to “too much, too little, or conflicting information” while waiting to see a specialist. Then, at the appointment, patients often “freeze up and forget to ask questions.” When physicians do answer patient questions, the information “goes in one ear and out the other.” [2] Evidence based interventions such as decision aids and communication aids have emerged to help patients meet these decision making and communication needs [3–5].

Decision aids are print or audio-visual materials designed to educate patients about treatment options and outcomes. In efficacy studies decision aids have been shown to increase patient knowledge and decrease decisional conflict [5–8], among other benefits. Communication aids, which include question lists, consultation summaries and audio-recordings, increase patient question-asking during consultations and information recall afterwards [9–16]. Decision and communication aids have been shown to be beneficial and are therefore ready for broader dissemination and implementation. However, a recent systematic review found only 17 studies reporting on implementations of either decision or communication aids [17].

We are the first to combine decision and communication aids in a single multi-component support program. In 2005, with support from a philanthropic foundation, we integrated decision and communication aids into our university-based breast cancer clinic using staff serving in paid internship positions. We designed our program, initially known as Decision Services (now the Patient Support Corps), using program theory [18] and the theory of diffusion of innovations [19], as described in a case study [20]. We used the RE-AIM framework (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance), to monitor and inform continuous improvements to our implementation [21, 22]. In response to calls for more research on the translation of evidence-based decision support interventions into practice [5, 17], we are now reporting on our findings. This report addresses the need for health services research on implementation and dissemination, addressing calls in the United Kingdom for more T3 research [23] and in the USA for more T2 research [24]. We report here on the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance as measured during the first seven years of our implementation.

Methods

From July 2005 through June 2012, we measured Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance of decision communication aids using the methods and measures outlined below. In order to minimize patient burden, we staggered the collection of data over different sample time frames.

Study setting, population, sample, design, timing

The study took place in the Breast Care Center at the University of California, San Francisco. The Breast Care Center is a high volume clinic providing multidisciplinary care in a National Cancer Institute-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center. The underlying population consisted of all the patients who made “new patient” appointments to see Breast Care Center specialists from July 2005 to June 2012. During this time period, the population was majority white (65 %), college-educated (85 %) and insured (60 % private insurance). We attempted to contact all these patients to offer coaching along with decision and communication aids. We solicited survey responses from those patients who accepted our materials or services, administering items by email or paper before and after they received decision aids; before and after question-listing sessions; before and after medical consultations; and four weeks after the first consultation. We changed the surveys every program year between 2005 and 2012 in order to measure different outcomes without increasing the burden of responding. We also analyzed records logged by staff in our program database. See Table 1 for sample time frames and collection dates and Table 2 for study participant demographics.

We obtained a waiver of written consent and ethics approval from the UCSF Committee on Human Research to abstract and de-identify our program records for research analysis and reporting purposes. In this manuscript we report on data not previously published, while also summarizing data reported in earlier publications [8, 14, 15, 20, 25–29].

Interventions –coaching in the use of decision and communication aids

Workforce

During the study period, our program personnel consisted of one part-time director (author JB), one part-time coordinator (author SV), and a revolving staff of interns (including authors ML, AT, and MZP). Each program year began with the arrival of new interns, as the prior year interns concluded their post-baccalaureate year and went on to medical school or graduate programs in science or public health. Each year, the director led a two day training workshop, teaching interns how to administer decision aids, elicit and document patient questions, and make notes and recordings while remaining neutral and non-directive. During a two-week overlap period, the new interns apprenticed with the departing interns, practicing under the supervision of experienced peers. The director and coordinator also supervised weekly case review meetings, provided interns with a detailed program manual, fielded intern queries by phone and email, and audited program records to assure quality.

Once trained, interns called patients two to three weeks prior to their consultation appointments to encourage the use of decision and communication aids (described below) and alerted patients verbally as well as by mail or email of other available resources such as our hospital’s Cancer Resource Center; patient health library; and online resources approved by Breast Care Center clinicians. Interns were each assigned a list targeting patients who had upcoming “new” or “new 60 minute” appointments to see a surgeon or medical oncologist and tasked with calling them a minimum of two times. Interns used interpreters when making phone calls to patients with language preferences indicated in the scheduling system. If patients did not respond to calls or reply to voicemails, interns sent them a template email describing and encouraging the use of decision and communication aids. Interns either enclosed these resources as links, or the email referred patients to resources being sent by mail, or available at the Cancer Resource Center.

Decision aids

In addition to calling and corresponding with our patients by email, program interns also routinely mailed one or more applicable decision aids to newly diagnosed patients before their decision-making appointments with doctors at the Breast Care Center. The five available decision aids, provided by the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation covered options and outcomes for treating ductal carcinoma in situ, early stage, and metastatic breast cancer.

Identifying and ordering applicable decision aids

We trained schedulers, practice assistances, call center staff and interns to identify, based on clinic notes and conversations with the patient, which decision aid(s) matched the patient diagnosis. Having found one or more applicable decision aids, the staff then typed a special code into the patient appointment record in our scheduling system. By looking for the appearance of this code in the scheduling system, our program coordinator then knew to mail out the decision aid(s) prior to the patient visit, or include a link to the decision aid(s) in an email.

Communication aids

Our interns coached patients to self-administer communication aids by suggesting patients (1) make a list of their questions; (2) bring a note-taker; and (3) make an audio-recording of the visit. The interns sent interested patients a prompt sheet by mail or email [30]. Interns also offered to accompany patients to their visits and administer the communication aids for them. In that scenario, an intern interviewed the patient for 20 to 60 minutes by telephone a few days before the clinic visit, and wrote down a word-processed list of the patient’s questions. The intern sent the question list to the physician in advance of the appointment; brought a laptop and digital audio-recorder to the visit to take notes and make a recording; and sent a summary of the notes and a compact disc copy of the audio-recording to the patient and physician.

During the question-listing session conducted by telephone, the intern followed a neutral, non-directive protocol called SLCT which stands for Scribing (writing down) the patient top-of-mind questions without interrupting; then Laddering or asking for elaboration on each of the initial questions; then Checking or administering a prompt sheet of additional topics; and finally Triaging the question list into a single page [31]. The interns used their training in summarizing and paraphrasing to write down the patient questions succinctly, while staying true to the patient intended meaning; and likewise summarized and paraphrased the physician’s advice and information in a neutral manner. Interns listened to the consultation audio recordings when necessary to assure the accuracy of their notes.

Due to the constrained availability of interns, we rationed our in-person services according to perceived patient need. Specifically, during the outreach calls, our interns placed patients on a waitlist and assigned each a priority level based on the intern’s assessment of need as well as the patient’s self-reported need for the service. Typically this dialogue generated a high priority level to patients who were unaccompanied, had limited English proficiency, were especially distressed or cognitively impaired, or who simply stated they would like to be considered high priority for their own reasons, disclosed or undisclosed.

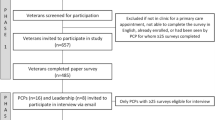

See Fig. 1 for an overview of the intervention timeline.

Sequence and timing of program interventions and surveys of effectiveness. This figure represents the sequence of interventions and surveys used during the study period. We used the survey time points to collect different data during different program years. See manuscript text for details. Abbreviations: DA = Decision Aid; CA = Communication Aid

Standardized measures and instruments for effectiveness

We asked patients who received decision and communication aids to complete surveys, respond to verbal prompts, or complete online surveys at five different time points as shown in Fig. 1. We used validated instruments with known psychometric properties to measure standard outcomes of decision support, summarized below, following the Ottawa Decision Support Framework [32, 33]. For study-specific outcomes, we created custom instruments of our own [34], which we briefly describe in each corresponding Results section.

To measure effectiveness in decision aids we asked patients to respond to questions measuring knowledge and decisional conflict. Respondents answered 3 to 6 multiple choice and open-ended condition-specific questions regarding treatment options for early-stage breast cancer decisions including surgery, reconstruction, and adjuvant therapy [8, 35, 36]. The knowledge items demonstrated good re-test reliability (intraclass correlation coefficient = 0.70) and content validity (discriminated between providers and patients – mean difference 35 %, p < 0.001) [37].

We also measured decisional conflict, defined as a state of uncertainty about the course of action to take [38]. The Decisional Conflict (DCS) scale is a 16-item Likert scale with a test-retest correlation coefficient of 0.81, and alpha coefficients ranging from 0.78 to 0.92 [38]. The version we used employed a response scale of 1 to 5 with 1 indicating the least amount of decisional conflict and 5 indicating the most. We asked respondents to respond to three of the five subscales (Informed, Values Clarity, and Uncertainty) from the Decisional Conflict Scale for a total of 9 questions before and after reviewing the decision aids.

To measure the effectiveness of our question-listing intervention, we used patient-reported self-efficacy. The Decision Self-Efficacy scale is an 11-item Likert scale measuring patients’ confidence in their ability to be informed and involved in treatment decisions [39]. The version we used employed a response scale of 1 to 5 with 1 indicating minimum confidence and 5 indicating maximum confidence. This scale was previously found to have acceptable psychometric properties and was sensitive to decision support interventions [40, 41].

To measure preparedness to make decisions, we used relevant items from the Preparation for Decision Making Scale [42]. Validation studies found this 10-item Likert scale had acceptable psychometric properties and was sensitive to decision support interventions [41]. To minimize patient response burden, we selected the most relevant items and adapted the wording to reflect our question-listing intervention: Did the question-listing session (and videos/booklets, if you received any) help you think about how involved you want to be in this discussion? Did the question-listing session (and videos/booklets, if you received any) help you identify the questions you want to ask? Did the question-listing session (and videos/booklets, if you received any) prepare you to talk to your doctor about what matters most to you? The response options were “1 – not at all,” “2 – a little,” “3 – somewhat,” “4 – quite a bit,” and “5 – a great deal.”

Results

Reach

Reach is defined as the absolute number, proportion, and representativeness of individuals who participate in a given initiative [22]. In the most recent program year of the study (2011-2012), out of 1,524 eligible patient appointments, we successfully contacted 1,212 (80 %); coached 1,110 (73 %) in the self-administered use of communication aids; sent 958 (63 %) decision aids; and provided staff-administered communication aids for 419 (27 %). Table 3 shows how our reach expanded over time, growing from 54 % to 73 % for patients coached in the self-administered use of communication aids; 25 % to 63 % for decision aids sent; and 17 % to 26 % for communication aids administered by staff. Over the study period (2005 to 2012), our staff sent a grand total of 5,153 decision aids and directly administered 2,004 communication aids.

In cases when our staff directly administered communication aids, we were confident that our efforts resulted in these interventions reaching patients. However, we were also interested in the reach of communication aids when we simply coached patients to self-administer them. Between January and September 2010, we surveyed 195 consecutive coached patients and received 82 responses (42 %). Four out of five (63/78 or 81 %) responded that they wrote a question list in response to our prompting, although only one of every four (14/61 or 23 %) said they showed it to their doctor. Two-thirds (51/77 or 66 %) said they brought a note-taker, but only 16/79 (20 %) reported making audio recordings. We have described these findings in greater detail in a prior publication and summarize them here for completeness [28].

Effectiveness

Decision aids

Of 1,553 surveys distributed between November 2005 and October 2008 to assess the effect of decision aids, we received 549 usable completed surveys (35 % response rate computed as survey responses divided by surveys sent). For the four early stage decision aids, our raw results showed 580 correct responses to 1275 questions prior to reviewing the decision aid (45 % correct) as compared to 938 correct responses to the same 1,275 questions after (74 % correct), a statistically significant increase in knowledge (p < 0.001). Overall respondents reported mean decisional conflict of 2.61 prior to viewing the decision aid, falling to 2.09 afterwards, a statistically significant decrease in decisional conflict (p < 0.001). Respondents rated their satisfaction with these decision aids at a mean of 4.2 out of a maximum of 5 [8].

Survey respondents found the decision aids helpful. Representative comments included:

-

“Your program helped me to focus and resulted in me changing treatment options. I know I made the right decision for me. I now sleep at night.”

-

“The video [Early Stage Surgery] was very helpful; I wish I could have had this info as reference when I had my first cancer occurrence.”

-

“It was helpful for me to see photos [Reconstruction] of women who have chosen different options after their mastectomy. I also appreciate the candid interviews of each of the women.”

We have described these findings in greater detail in a prior publication and summarize them here for completeness [8].

Communication aids

We evaluated decision self-efficacy before and after question-listing sessions over an 18-month period (January 2007 through June 2008). We collected surveys from 321/362 sessions (89 % response rate) resulting in 242 matching pairs with responses for at least 10 of the 11 items both before and after. The mean decision self-efficacy before the question-listing session was 4.20 (95 % confidence level 4.10 to 4.29) rising to 4.45 (95 % confidence level 4.37 to 4.53) afterwards, a statistically significant increase of 0.25 (paired t-test p < 0.001). See Fig. 2.

To reduce patient burden, we subsequently surveyed patients about a single item measure, “I know what questions to ask my doctor,” which we felt captured the essence of our question-listing program. Between May and December 2009, we collected 161 surveys before and after 209 question-listing sessions (77 % response rate) resulting in 137 matched pairs. The mean before the question-listing session was 6.6 (95 % confidence interval 6.2 to 7.0) and after was 8.0 (95 % confidence interval 7.7 to 8.4). This shows a statistically significant increase of 1.4 (paired t-test p < 0.001). See Fig. 3.

From July 2009 through June 2012 patients completed 416 questionnaires that included three items from the Preparation for Decision Making Scale while waiting in the exam room to see their specialists for 557 appointments (75 % response rate). Most (297/378 or 79 %) responded the question-listing session had helped them “4 – quite a bit” or “5 – a great deal” think about how involved they wanted to be in the discussion (mean 4.17). Most (283/374 or 75 %) responded the question-listing session had helped them “4 – quite a bit” or “5 – a great deal” to identify the questions they wanted to ask (mean 4.02). Most (309/377 or 82 %) responded the question-listing session had helped them “4 – quite a bit” or “5 – a great deal” prepare them to talk to their doctor about what matters most to them (mean 4.25). See Fig. 4.

To measure the impact of the pre-visit question-listing intervention, we tabulated the number of questions patients emailed to us before our question-listing sessions or dictated to us over the phone for 36 months (July 2009 through June 2012). We collected data before and after 1,016 of 1,032 question-listing sessions (98 % response rate) resulting in 1,001 matched pairs. The mean number of questions before the question-listing session was 10 (95 % confidence interval 8.9 to 10.3) and after was 24 (95 % confidence interval 22.9 to 24.6). This shows a statistically significant increase of 14 (paired t-test p < 0.001; 95 % confidence interval 13.4 to 14.8). See Fig. 5.

From July 2009 through June 2012 we asked how satisfied patients had been with their pre-visit interventions immediately before seeing their providers. We collected 822 responses from 1,124 patients (73 % response rate). On a scale from zero to 10 the mean satisfaction rating was 9.3 See Fig. 6.

Regarding program effectiveness for staff, respondents to our survey of intern alumni (21/47 or 45 %) reported that their participation in Decision Services increased their perceived medical competencies across the board, while making the biggest contribution to respondent growth in systems-based practice and patient care. One respondent wrote, “Decision Services helped me actually learn the art of listening through practice, patience, and silence.” Another wrote, “After working for Decision Services, I think I was maximizing my potential in compassion and propriety in working with patients. This carried with me through medical school.” We previously reported on this intern survey in the literature [29].

Adoption

Directly administered communication aids

We defined patient adoption as the level of patients’ acceptance, use of, satisfaction with, and willingness to recommend to others, our program interventions. From July 2009 through June 2012 there were 4,295 new visitors with new patient appointments, whom we monitored regarding adoption of direct assistance with communication aids. We spoke with 3,034 (71 %) of the 4,295 we tried to contact. We called during business hours and left at least two voice mail messages encouraging patients to call us back. When we had an email address on record for the patient, our second voicemail indicated we would be sending an email describing available resources and providing our contact information. More than half of those new visitors reached by telephone (1,675/3,034 or 55 %) accepted an intern offer to directly administer communication aids. We placed these on our waitlist and ranked them according to urgency of need for our services. One in three of the new visitors we spoke with (1,037/3,034 or 34 %) declined, often citing the accompaniment of a family member or friend to take notes. The remaining 11 % (322/3,034) were not eligible, because they didn’t know their diagnosis, or the consultation was to confirm a diagnosis, or they did not have breast cancer.

A total of 55 % of new patient visitors initially accepted our offer of direct assistance (1,675/4,295) from July 2009 through June 2012. We delivered direct assistance to 26 % of all new patient visitors (1,124/4,295), representing 67 % of those on the waitlist (1,124/1,675).

Of the new patients who initially accepted, 2 % (33/1,675) canceled their appointments, 7 % (117/1,675) changed their minds, and we lacked capacity to serve the remaining 24 % (401/1,675).

From July 2009 through June 2012, four weeks after their consultations, we asked visitors who had received communication aids to tell us which communication aids they had reviewed, shared with anyone, and would recommend to others. We collected 489 responses from 978 patients (50 % response rate) who had received communication aids. Seventy percent of respondents (249/358) indicated they had reviewed the question-list since the appointment, 60 % (220/367) had listened to the recording, and 86 % (297/344) had reviewed the summary since the appointment. Other results showed high recommendation rates for the question list, consultation summary, and consultation recording (see Table 4).

Decision aids

On the same four-week follow-up survey we asked all visitors who had received decision aids to report on how much of each they had reviewed, if they had shared them with anyone else, and if they would recommend them to others. We sent a total of 1,812 survey invitations to patients who had received any decision or communication aids between July 2009 and June 2012. The 741 respondents (41 %) had received a total of 1,195 decision aids. Of the 1,195 decision aids received, patients had reviewed “all” or “some” of 792/1195 (66 %) of the videos and had reviewed “all” or “some” of 980/1195 (82 %) of the booklets (see Table 4). Representative patient comments included:

-

“I have reviewed the Summary notes several times, and was glad to have the recording to more easily recall what was discussed.”

-

“I think it is wonderful and incredibly helpful to call patients and offer to accompany them to their consultation. In addition, the person I talked with recommended I bring a tape recorder and I now do so for almost all appointments. This is a valuable service that supports patients in the process of making difficult decisions and helps patients develop skills to promote their own health.”

-

“After receiving the services, especially the notes from the Oncology Doctor visit, I read through the extensive, well organized notes [Intern] transcribed. I was incredibly surprised that I had only remembered about one-third or less of what the doctor said. I have referred back to these notes many times. This is an invaluable service to any patient.”

-

“I really appreciated the consultation recording. Even though I haven’t felt the need to review it again, it gave me a very secure feeling that everything I discussed with Dr. [redacted] was being recorded so I did not have to worry about whether we (I and my friend) were taking good and complete notes. If I had wondered about any aspect of the visit, I knew I could go back and review it at any time. The consultation summary was extremely helpful, and one reason I have not gone back to review the actual recording.”

Physicians

Regarding adoption by physicians, we found universal cooperation among physicians, in the sense that all 22 agreed a priori to allow the use of decision and communication aids, whether administered by patients or staff. One physician joining the practice expressed reservations about being recorded, but agreed to try it for a month, and ultimately agreed to continue. Physicians were also generally collaborative in incorporating the decision and communication aids, and interns, into the consultation, for example by referring to the question list or repeating complex information for the note-taker to capture, or endorsing the use of decision and communication aids to put patients at ease. We reviewed intern process notes and found many examples of physician collaboration, such as:

-

“He let the patient know that he had reviewed her questions and also used it [the question list] to go over her choices”

-

“[MD] said he had read through the consultation plan and that I was getting down everything on the recorder and in my notes.”

These and other details are available from our qualitative analysis of intern process notes, published in the literature [27].

Implementation

At the setting level, implementation refers to our fidelity to the various elements of a program protocol [22]. A major success factor in our implementation was the fact that the Breast Care Center leadership was willing to subsidize the participation of their staff in this job enrichment program by donating one day per week of each intern’s time. We wanted to make sure the staff was maximally engaged in obtaining the patient interaction experience we promised them. This led us to measure exploitation of staff capacity, or the proportion of available staff time used for direct patient support in our program. To quantify staff capacity we calculated the number of patients our interns could potentially accompany each month and compared it to the actual number of patients actually accompanied that month.

Over the first program year we exploited 142/496 (29 %) of our staff capacity. By 2011-2012, we had improved our exploitation of staff capacity to 84 % (419/500). See Table 3 to see the trajectory of workforce capacity exploitation. Overall, our most important innovation was to design an outbound calling program whereby our interns call patients and coach them, rather than wait for patients to self-refer or count on schedulers to refer them [8, 25], .

Maintenance

Starting in 2004, the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation provided materials (decision aids) and funding to UCSF to support our program as a demonstration project, exploring the feasibility of integrating evidence-based decision and communication aids into practice. These external funds supported program design and implementation activities, along with data collection, analysis, and reporting. Upon expiration of external funding after the 2012 program year, the Breast Care Center continued its support of the program interns and took over 50 % funding of the program coordinator (approximately $45,000 including fringe benefits). We interpreted this commitment of resources as evidence of institutionalization at the Breast Care Center. The Breast Care Center also committed annual funds in the amounts of $3,000 for the program database, and $700 for mailing the decision aids. We therefore estimate the program’s maintenance costs at approximately $150,000 per year for paid interns, a coordinator, and supplies.

Over the course of our program history, UCSF patients outside the Breast Care Center also expressed interest in accessing our program. Administrators and clinical leaders endorsed the idea of expanding our program, but told us they did not have sufficient resources to pay interns. To address this barrier to further institutionalization, we obtained a grant from an innovation fund at our institution to explore using part-time unpaid interns alongside full-time paid interns.

Based on our findings, we implemented an affiliation agreement with the University of California, Berkeley nearby. The affiliation agreement specifies the legal, privacy, and risk management provisions required to safely and effectively deploy students in our clinical setting. We then demonstrated, in a small scale implementation, the feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of using students alongside our interns, inside as well as outside the Breast Care Center [43]. Two UC Berkeley students received academic credit for this service learning internship, delivering the question-listing, note-taking and audio recording services to six patients with appropriate fidelity to our program design.

We are therefore deploying unpaid interns alongside our paid interns in the Breast Care Center and using unpaid interns as a workforce to expand to other units. A hospital auxiliary foundation has provided a grant of $30,000 to launch the Patient Support Corps and we have trained 12 UC Berkeley student interns to support patients in the fertility preservation, gynecologic oncology, radiation oncology, urology, head and neck, colorectal, melanoma, orthopaedic, and spine clinics.

Discussion

Interpretation of results and connections to the literature

Reach

Our program has evolved to be distinct from others in our use of interns to call all of our clinic patients and coach them in the use of both decision and communication aids. Other programs have reported systematic distribution of decision aids alone, through staff or schedule-based requisitioning systems [44, 45]. Some have evaluated coaching in response to inbound calls [46, 47], including in combination with the distribution of decision aids [48]. We noted a finding in the literature that broad mailings could be associated with inappropriate materials in 20 % of cases [49]. When in doubt, rather than taking a best guess at the appropriate decision aid and sending it, the interns now tell patients to ask their provider which program might be best for them at the consultation.

Our reach of communication aids directly administered by program staff has stabilized at 1 in 4 due to our limits in capacity and the challenges of synchronizing intern availability with patient visits. We are encouraged that 81 % of respondents to our survey reported self-administering one or more communication aids based on our prompting. Implementation studies of question prompting, which invite patients to circle frequently asked questions and add their own via a sheet distributed by clinic personnel in person or by mail, found similar reach as our staff coaching patients to self-administer our prompt sheet [50, 51].

Effectiveness

In our implementation, we found similar effectiveness as predicted by systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials of decision and communication aids [5, 41, 52]. The decision aids were associated with increased knowledge, consistent with findings in a systematic review confined to breast cancer [53]. Communication aids were associated with increased self-efficacy, increased number of questions, and high levels of satisfaction and ability to access information for recall purposes, also consistent with prior efficacy studies [54–57]. We found higher numbers of questions (mean 24) than were reported in the intervention arms in prior studies of question-prompting interventions (means ranged from 6-15) [3, 55, 58, 59].

Adoption

Our results for patient viewing of decision aids, at 68 % (videos) to 82 % (booklets), were higher than the few other reports in the literature. Viewing rates have been reported at 25 % [49], and 38 % to 44 % [60] for decision aids. We attribute our higher rates to the fact that many of our patients reviewed the decision aids in preparation for a scheduled pre-consultation question-listing session with an intern. In essence, we gave patients a homework assignment with a deadline, and used the results of their decision aid review in a functional task, question-listing, which benefited them.

Listening rates in our study were equal to or lower, at 60 %, than in efficacy studies of audio-recordings. Under efficacy study conditions, patients have reported listening at rates of 60 % [4, 61], 75 % [56] and 89 % [58]. Patients in those studies may have been more likely to listen as a result of their study participation, whereas our patients did not know that they would be asked about their listening habits. Some patients wrote in follow-up survey comments that they appreciate having the recordings as a safety net, whether or not they listen to them.

Implementation

Our primary concern about implementation has been to fully exploit the capacity of our paid interns. After we switched to outreach by interns, our capacity exploitation increased to acceptable levels that would sustain sponsor and staff interest (now 84 %). We also initiated a waitlist inspired by queuing theory in optimization [62]. This waitlist allowed us to synchronize intern availability with patient demand, according to the priority of patient needs.

Maintenance

We launched our program with support from an external Foundation, which no longer provides funding. The Breast Care Center now sustains the program from its discretionary funds. In order to expand our program affordably, we are deploying student interns alongside paid interns. The student interns obtain academic credit for the service learning experience of coaching patients in the use of communication aids. We call this initiative the Patient Support Corps and are replicating it at other clinics and educational institutions.

Study quality

The strengths of this study are that it reports on the only sustained implementation integrating coaching and decision and communication aids. We report on our translation of evidence-based decision and communication aids after evaluating the five RE-AIM dimensions of our program. We staggered the data collection for Effectiveness into separate phases so as to minimize the response burden on any given patient.

While RE-AIM is a well-accepted framework for implementation research, it emphasizes external validity, or the potential relevance of findings to real-world settings, over internal validity, or the rigor of inferences within the study. Indeed, this study has all the limitations of any pragmatic field evaluation, including relatively low internal validity for our inferences, as we lacked random assignment and control groups. We also experienced relatively low response rates for surveys administered online, by mail, or by telephone, outside of our in-clinic interactions with patients. For in-clinic surveys, we had high response rates but could have experienced agreement bias as the same staff often administered both interventions and surveys.

Conclusions

We conclude that our sustained implementation of coaching with decision and communication aids has successfully translated evidence-based support strategies into practice. Our support program now has broad reach. We have seen the effectiveness predicted by prior randomized controlled trials, in terms of patient knowledge, decisional conflict, preparation for decision-making, satisfaction, self-efficacy, number of questions, and access to information for recall purposes. Patients have adopted the decision and communication aids, reviewing them and sharing them with others. We have adhered to the implementation plan for our interns, offering them the promised job enrichment featuring weekly patient interaction.

We have successfully integrated our program into the clinic workflow, minimizing clinic burden while enriching patient experiences. We have found satisfaction from all parties involved, including patients, interns, and physicians. We have maintained our implementation for over 7 years, with plans to sustain the program with students as well as interns.

We connected over 4,500 individuals with support for making high stakes, high stress decisions. We introduced 22 physicians and dozens of residents, fellows, nurses, and other health care specialists to these concepts and turned them into advocates for decision support. We trained 84 paid staff interns and 20 unpaid student interns participate in a patient-centered high-touch supportive service. Our model is evidence that this sort of program can be successfully integrated into specialty care and will contribute to patients making informed decisions with their attending physicians. For those sites that lack resources to pay coaches, our findings suggest that unpaid student interns can gain academic credit and experience while effectively delivering evidence-based decision and communication aids.

Abbreviations

- CA:

-

Communication aid

- DA:

-

Decision aid

- DCIS:

-

Ductal carcinoma In Situ

- NA:

-

Not available

- PY:

-

Program year

- RE-AIM:

-

Reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance

- SCOPED:

-

Situation, choices, objectives, people, evaluation, decision

- SLCT:

-

Scribe, ladder, check, triage

References

How many women get breast cancer? [http://www.cancer.org/cancer/breastcancer/overviewguide/breast-cancer-overview-key-statistics]. Accessed March 30, 2015.

Belkora JK, Miller MF, Dougherty K, Gayer C, Golant M, Buzaglo JS: The need for decision and communication aids: a survey of breast cancer survivors. J Community Support Oncol 2015, 13:104–112.

Brown R, Butow PN, Boyer MJ, Tattersall MH. Promoting patient participation in the cancer consultation: evaluation of a prompt sheet and coaching in question-asking. Br J Cancer. 1999;80:242–8.

Hack TF, Pickles T, Bultz BD, Ruether JD, Weir LM, Degner LF, et al. Impact of providing audiotapes of primary adjuvant treatment consultations to women with breast cancer: a multisite, randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Oncol Off J Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2003;21:4138–44.

Stacey D, Legare F, Col NF, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, Eden KB, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;1:CD001431.

Whelan T, Levine M, Willan A, Gafni A, Sanders K, Mirsky D, et al. Effect of a decision aid on knowledge and treatment decision making for breast cancer surgery – a randomized trial. JAMA. 2004;292:435–41.

Obeidat R, Finnell DS, Lally RM. Decision aids for surgical treatment of early stage breast cancer: a narrative review of the literature. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85:e311–21.

Belkora JK, Volz S, Teng AE, Moore DH, Loth MK, Sepucha KR. Impact of decision aids in a sustained implementation at a breast care center. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:195–204.

Bruera E, Pituskin E, Calder K, Neumann CM, Hanson J. The addition of an audiocassette recording of a consultation to written recommendations for patients with advanced cancer: A randomized, controlled trial. Cancer. 1999;86:2420–5.

Brown RF, Butow PN, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH. Promoting patient participation and shortening cancer consultations: a randomised trial. Br J Cancer. 2001;85:1273–9.

Tattersall MH, Butow PN. Consultation audio tapes: an underused cancer patient information aid and clinical research tool. Lancet Oncol. 2002;3:431–7.

Liddell C, Rae G, Brown TR, Johnston D, Coates V, Mallett J. Giving patients an audiotape of their GP consultation: a randomised controlled trial. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:667–72.

Belkora J, Katapodi M, Moore D, Franklin L, Hopper K, Esserman L. Evaluation of a visit preparation intervention implemented in two rural, underserved counties of Northern California. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64:350–9.

Belkora JK, Loth MK, Chen DF, Chen JY, Volz S, Esserman LJ. Monitoring the implementation of Consultation Planning, Recording, and Summarizing in a breast care center. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:536–43.

Belkora J, Edlow B, Aviv C, Sepucha K, Esserman L. Training community resource center and clinic personnel to prompt patients in listing questions for doctors: follow-up interviews about barriers and facilitators to the implementation of consultation planning. Implement Sci. 2008;3:6.

Dimoska A, Tattersall MH, Butow PN, Shepherd H, Kinnersley P. Can a “prompt list” empower cancer patients to ask relevant questions? Cancer. 2008;113:225–37.

Elwyn G, Scholl I, Tietbohl C, Mann M, Edwards A, Clay C, et al. “Many miles to go …”: a systematic review of the implementation of patient decision support interventions into routine clinical practice. BMC Med Inform Decision Making. 2013;13:S14.

Rossi PH, Freeman HE, Lipsey MW. Evaluation - A Systematic Approach. 6th ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications; 1999.

Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovations. 5th ed. New York: Free Press; 2003.

Belkora JK, Loth MK, Volz S, Rugo HS. Implementing decision and communication aids to facilitate patient-centered care in breast cancer: a case study. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;77:360–8.

Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003;93:1261–7.

RE-AIM Framework: Reach of Health Behavior Interventions [http://www.re-aim.hnfe.vt.edu/about_re-aim/what_is_re-aim/index.html]. Accessed March 30, 2015.

Rubio DM, Schoenbaum EE, Lee LS, Schteingart DE, Marantz PR, Anderson KE, et al. Defining translational research: implications for training. Acad Med. 2010;85:470–5.

Westfall JM, Mold J, Fagnan L. Practice-based research–“Blue Highways” on the NIH roadmap. JAMA. 2007;297:403–6.

Belkora JK, Teng A, Volz S, Loth MK, Esserman LJ. Expanding the reach of decision and communication aids in a breast care center: a quality improvement study. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;83:234–9.

Pass M, Belkora J, Moore D, Volz S, Sepucha K. Patient and observer ratings of physician shared decision making behaviors in breast cancer consultations. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;88:93–9.

Pass M, Volz S, Teng A, Esserman L, Belkora J. Physician behaviors surrounding the implementation of decision and communication AIDS in a breast cancer clinic: a qualitative analysis of staff intern perceptions. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2012;27:764–9.

Volz S, Moore DH, Belkora JK: Do patients use decision and communication aids as prompted when meeting with breast cancer specialists? Health Expect 2015, 18:379-391.

Zarin-Pass M, Belkora J, Volz S, Esserman L. Making better doctors: a survey of premedical interns working as health coaches. J Cancer Educ Off J Am Assoc Cancer Educ. 2014;29:167–74.

SCOPED prompt sheet [http://www.decisionservices.ucsf.edu/question-prompts/]. Accessed March 30, 2015.

SLCT Process [www.slctprocess.org]. Accessed March 30, 2015.

Cranney A, O‘Connor AM, Jacobsen MJ, Tugwell P, Adachi JD, Ooi DS, et al. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. Patient Educ Couns. 2002;47:245–55.

Legare F, O’Connor AC, Graham I, Saucier D, Cote L, Cauchon M, et al. Supporting patients facing difficult health care decisions: use of the Ottawa Decision Support Framework. Can Fam Physician. 2006;52:476–7.

Helfrich CD, Damschroder LJ, Hagedorn HJ, Daggett GS, Sahay A, Ritchie M, et al. A critical synthesis of literature on the promoting action on research implementation in health services (PARIHS) framework. Implement Sci IS. 2010;5:82.

Lee CN, Belkora J, Chang Y, Moy B, Partridge A, Sepucha K. Are patients making high-quality decisions about breast reconstruction after mastectomy? [outcomes article]. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:18–26.

Lee CN, Chang Y, Adimorah N, Belkora JK, Moy B, Partridge AH, et al. Decision making about surgery for early-stage breast cancer. J Am Coll Surg. 2012;214:1–10.

Sepucha KR, Belkora JK, Chang Y, Cosenza C, Levin CA, Moy B, et al. Measuring decision quality: psychometric evaluation of a new instrument for breast cancer surgery. BMC Med Inform Decision Making. 2012;12:51.

O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30.

User Manual -- Decision Self-Efficacy Scale [http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_Decision_SelfEfficacy.pdf]. Accessed March 30, 2015

Bunn H, O’Connor A. Validation of client decision-making instruments in the context of psychiatry. Can J Nurs Res. 1996;28:13–27.

Pitkethly M, MacGillivray S, Ryan R. Recordings or summaries of consultations for people with cancer. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001539. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001539.pub2.

User Manual -- Preparation for Decision Making Scale [http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/develop/User_Manuals/UM_PrepDM.pdf]. Accessed March 30, 2015.

Belkora J, Zarin-Pass M, Forbes L, Goldstein A, Volz S, Bloom J: The Patient Support Corps: Program Design for Patients Delivering Decision Support. In International Shared Decision Making Conference: Lima, Peru. 2013

Lin GA, Halley M, Rendle KA, Tietbohl C, May SG, Trujillo L, et al. An effort to spread decision aids in five California primary care practices yielded low distribution, highlighting hurdles. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32:311–20.

Hsu C, Liss DT, Westbrook EO, Arterburn D. Incorporating patient decision aids into standard clinical practice in an integrated delivery system. Med Decis Making. 2013;33:85–97.

Stacey D, O’Connor AM, Graham ID, Pomey MP. Randomized controlled trial of the effectiveness of an intervention to implement evidence-based patient decision support in a nursing call centre. J Telemed Telecare. 2006;12:410–5.

Stacey D, Pomey MP, O’Connor AM, Graham ID. Adoption and sustainability of decision support for patients facing health decisions: an implementation case study in nursing. Implement Sci. 2006;1:17.

Wennberg DE, Marr A, Lang L, O’Malley S, Bennett G. A randomized trial of a telephone care-management strategy. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1245–55.

Brackett C, Kearing S, Cochran N, Tosteson AN, Brooks W. Strategies for distributing cancer screening decision aids in primary care. Patient Educ Couns. 2009;78:166–8.

Dimoska A, Butow PN, Lynch J, Hovey E, Agar M, Beale P, et al. Implementing patient question-prompt lists into routine cancer care. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;86:252–8.

Glynne-Jones R, Ostler P, Lumley-Graybow S, Chait I, Hughes R, Grainger J, et al. Can I look at my list? An evaluation of a ‘prompt sheet’ within an oncology outpatient clinic. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2006;18:395–400.

Kinnersley P, Edwards AGK, Hood K, Cadbury N, Ryan R, Prout H, Owen D, MacBeth F, Butow P, Butler C. Interventions before consultations for helping patients address their information needs. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2007, Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004565. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004565.pub2.

Waljee JF, Rogers MA, Alderman AK. Decision aids and breast cancer: do they influence choice for surgery and knowledge of treatment options? J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1067–73.

Roter DL. Patient question asking in physician-patient interaction. Health Psychol. 1984;3:395–409.

Butow PN, Dunn SM, Tattersall MH, Jones QJ. Patient participation in the cancer consultation: evaluation of a question prompt sheet. Ann Oncol. 1994;5:199–204.

Ong LM, Visser MR, Lammes FB, van Der Velden J, Kuenen BC, de Haes JC. Effect of providing cancer patients with the audiotaped initial consultation on satisfaction, recall, and quality of life: a randomized, double-blind study. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:3052–60.

Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, Devine RJ, Simpson JM, Aggarwal G, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:715–23.

Bruera E, Sweeney C, Willey J, Palmer JL, Tolley S, Rosales M, et al. Breast cancer patient perception of the helpfulness of a prompt sheet versus a general information sheet during outpatient consultation: a randomized, controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2003;25:412–9.

Butow P, Devine R, Boyer M, Pendlebury S, Jackson M, Tattersall MH. Cancer consultation preparation package: changing patients but not physicians is not enough. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4401–19.

Uy V, May SG, Tietbohl C, Frosch DL: Barriers and facilitators to routine distribution of patient decision support interventions: a preliminary study in community-based primary care settings. Health Expect 2014, 17:353-364.

Tattersall MH, Butow PN, Griffin AM, Dunn SM. The take-home message: patients prefer consultation audiotapes to summary letters. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1305–11.

Winston WL. Operations research : applications and algorithms. Boston: Duxbury Press; 1987.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation and the University of California, San Francisco, Breast Care Center. Authors JB, SV, ML, AT, and MZP drew partial salary support from a demonstration project grant (#0015) provided by the Informed Medical Decisions Foundation. The Foundation is a non-profit corporation that co-developed the breast cancer decision aids described in this report, and supplied them at no charge to the Decision Services unit of the Breast Care Center as part of the Foundation’s research and dissemination agenda. The decision aids were co-developed and distributed commercially by Health Dialog, a subsidiary of Bupa Health Assurance Limited, a global provider of health services based in the United Kingdom.

A grant from the Foundation provided funding for Decision Services’ core operations and data collection, analysis, and reporting activities. The UCSF Breast Care Center funded our field operations, including infrastructure, personnel and supplies. During the study period, the Decision Services unit was also sustained by gifts and donations from individuals and organizations including the Safeway Foundation and the Wells Fargo Foundation. The funding sources had no involvement in any aspect of this implementation study.

The authors would like to thank the patients who took the time to reply to our surveys. The entire faculty and staff of the Breast Care Center cooperates with the integration of decision support into the clinic. In addition, faculty and managers allow their paid interns to serve as staff in our support program one day per week. Many employees of the Breast Care Center, including the paid interns, assist with data collection. The internship program is grateful to Meredith Buxton, who administers the overall internship program, and Amy Boebel, a donor, for endowing the leadership development component of the internship program. We also wish to acknowledge Gail Sorrough and her team at the Fishbon Memorial Library at the University of California, San Francisco, for their ongoing assistance with research; and to Ann Griffin at the UCSF Cancer Registry for ongoing assistance with patient population statistics.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The funding sources of the program (see Acknowledgements) had no involvement in any aspect of this implementation study.

Authors’ contributions

Author JB is responsible for the overall design of the implementation and its evaluation and is primary author of the manuscript. SV managed the overall data collection and data analysis and is a major contributor to the drafting and revisions of this manuscript. Authors ML, AT and MZP collected data, conducted data analysis and contributed multiple revisions to this manuscript. DM provided critical statistical analysis and both DM and LJE contributed to revising the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Belkora, J., Volz, S., Loth, M. et al. Coaching patients in the use of decision and communication aids: RE-AIM evaluation of a patient support program. BMC Health Serv Res 15, 209 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0872-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0872-6