Abstract

Background

Patients generate large amounts of digital data through devices, social media applications, and other online activities. Little is known about patients’ perception of the data they generate online and its relatedness to health, their willingness to share data for research, and their preferences regarding data use.

Methods

Patients at an academic urban emergency department were asked if they would donate any of 19 different types of data to health researchers and were asked about their views on data types’ health relatedness. Factor analysis was used to identify the structure in patients’ perceptions of willingness to share different digital data, and their health relatedness.

Results

Of 595 patients approached 206 agreed to participate, of whom 104 agreed to share at least one types of digital data immediately, and 78% agreed to donate at least one data type after death. EMR, wearable, and Google search histories (80%) had the highest percentage of reported health relatedness. 72% participants wanted to know the results of any analysis of their shared data, and half wanted their healthcare provider to know.

Conclusion

Patients in this study were willing to share a considerable amount of personal digital data with health researchers. They also recognize that digital data from many sources reveal information about their health. This study opens up a discussion around reconsidering US privacy protections for health information to reflect current opinions and to include their relatedness to health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

In 2012, the retailer Target sent advertisements for baby products to a teen who had not disclosed her pregnancy to her parents. Target had concluded the teen was pregnant after she purchased items like unscented lotion and cotton balls, which figured into algorithms predicting pregnancy [1]. The algorithm was allegedly accurate, but the tracking practices of Target were criticized after it was reported to the public [1, 2]. Individual customers reportedly complained and reported that predicting pregnancy from purchases was “creepy” [1]. After the public response Target was reported to have modified its marketing practices, instead of only sending baby supply coupons to women that their algorithm deemed pregnant, Target would send baby supply coupons with other home goods items mixed in [1]. “As long as a pregnant woman thinks she hasn’t been spied on, she’ll use the coupons” [2]. The sensitive nature of early pregnancy makes the practice of targeted marketing seem particularly invasive. There are many regulations enacted to protect traditional clinical health information, but there is less guidance for how health related digital data should be protected.

Contemporary practices to safeguard the privacy of health related data, such as HIPAA privacy rules, emerged at a time when health data were largely seen as the products of clinical encounters [3]. But health is revealed in a wide range of individual behaviors that occur outside the health care system—in purchases, communications, searches, locations—and an increasing share of those activities are captured electronically where they can be linked and analyzed. These data offer promise to advance research on individual or public health – for instance in uncovering insights on manifestations and sequelae of mental health, hospital encounters, and outbreaks [4]. Public acceptability of using these data for health purposes is, however, unknown and likely dynamic [5]. The promise of applying disparate digital data to health insights sits alongside enormous practical uncertainties about logistics, acceptability, perceived and actual value.

Prior work suggests that many individuals are willing to share substantial personal information but do not like to be surprised by how their data are used [5]. The contextual integrity theory includes the idea that perceptions of privacy are based on ethical concerns that evolve over time [6]. The use of proprietary algorithms to categorize individuals on the basis of behaviors or tendencies can be viewed as ‘creepy.’ In the context of health care, prior work has found that 85% of patients who reported using social media and who were willing to participate in research also agreed to share these data sources and have them linked to their electronic health record for health research [7]. That consent was provided in the context of active patient care, where trust, and also perhaps perceptions of information safeguards, are typically high. Beyond social media however, little is known about what other digital traces patients would willingly share with health researchers, under what circumstances, and for what reason [8].

We used a deception design to credibly evaluate participants’ willingness to share data, the health relatedness of those digital data sources, and preferences associated with data sharing (e.g. desired information to receive in return and the individuals with whom participants were willing to share).

Methods

Aim, design and setting

Patients seeking care in a high volume, urban, academic Emergency Department from July to November 2017 were approached by research assistants for study participation. Excluded were patients 1) < 18 years old, 2) non-English speaking, or 3) High acuity and Trauma Level I. Patients were asked to participate in a survey about digital data and informed that consenting participants would be eligible for a 1 in 50 chance of winning a $40 gift card.

Survey instrument

The 18-question survey (Additional file 1 of the supplementary material), administered to participants on a laptop or tablet, had 5 core components: willingness to donate data for health research (now and at death), health relatedness of digital data, prior experiences with data privacy, data sharing preferences and concerns, and demographic information.

We asked participants about 19 different types of digital data: Facebook, Twitter, Snapchat, Instagram, EMR, genetic data, prescription history, fitness trackers, credit card purchases, tax records, online purchase history, Google searches, music streaming, Yelp reviews, rideshare history, GPS data, email and text message data. These data types were chosen based on a larger project that the Center for Digital Health is conducting.

In an IRB-approved deception design, participants were asked if they would consider donating any of the 19 different data types to health researchers, and were told that if they selected “Yes” that they would be directed to do so immediately, to simulate an actual real time response. Upon finishing this question block, participants were informed that they would not actually be donating their data, and were directed to subsequent survey questions. Participants used a 5-point scale to report how strongly they felt that various types of digital data contained health-related information.

Participants were asked what data they might choose to donate to researchers, what concerns they would have about data donation (e.g. fraud, abuse, misidentification), and who (e.g. friends, family, physician) they would want to have access to their information [9].

Analysis

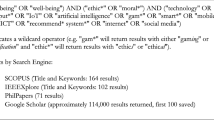

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize each of the components of the survey. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was conducted to identify clusters of different data sources grouped according to participants’ sense of health-relatedness and willingness to share. EFA was conducted in R 3.5.1 using Parallel analysis [10, 11] comparing the scree of factors of the observed data with that of a random data matrix of the same size.

Results

Of 595 people approached, 206 (35%) consented to participate. Participants were primarily young, female, African-American, and lower income (Table 1).

Willingness to donate digital data for health research

Participants’ willingness to share 19 specific types of digital data with researchers at the time of the survey and after death are reported in Fig. 1. One hundred four participants (65%) agreed to share at least one digital data type listed in the survey. Participants were more willing to share digital data after death for all data types.

Factor analysis revealed 6 discrete themes grouping different types of data according to patient willingness to share (Table 2). Based on the dominant content of these data, we interpreted these groupings as Health/location, Social Media, Other activities, Politics, Communication, Financial. Additional file 2: Figure S1 (in the supplement) shows the percentage of patients who reported using the indicated devices or accessing the type of data listed.

Health relatedness of digital data

Figure 2 reports participants’ assessments of the health relatedness of different data sources. Of note, Google search histories, data from wearables, and email were considered more health related than genetic data.

Factor analysis revealed 5 discrete themes grouping different types of data according to perceived health relatedness (Table 3). Based on the dominant content of these data, we interpreted these groupings as Social Media, Health, Financial/location, Apps, Communication/commerce.

Data sharing preferences and concerns

Patients were most interested in receiving feedback about potential risk factors 139 (67%) gleaned from their data; 155 patients (72%) wanted the information shared with themselves and 111 (51%) with a health care provider. Only 8 individuals (4%) said they would share health insights with their social network (Table 4).

Patients also expressed concerns about potential data and privacy breaches; a majority were concerned that friends online might inappropriately disclose private information to others 115 (56%), that they might be defrauded online or their personal information would be abused 149 (73%), that companies might share information with third parties without consent 153 (74%), and that companies and websites might use their information in ways not stated in the privacy policies or user agreements 149 (72%).

Discussion

This study has three main findings. First, patients in this study were willing to share several non-traditional forms of data with health researchers now and even more so after they have died. Second, a non-trivial percentage of patients recognized that digital footprints left in non-health areas such as finance or commerce may reveal information about their health. Third, these patients have preferences about what health related insights they would want to learn from their digital data and with whom they would want to share this information, and potential pitfalls of digital data sharing.

Participants were willing to share many types of digital data with researchers, some revealing a willingness to share presumably sensitive data like tax records and credit card purchases. These financial data sources may be highly predictive of health and health outcomes [12]. There are many steps however between sharing and actionable information [13, 14]. Each data source provides different signal, and the extent of the potential signal is likely mediated by the amount of data shared, and how individualized that data are. A growing literature addresses correlations between digital data and health outcomes and health care utilization [15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22]. Much of this research relies on participants sharing personal data with researchers. Less is known however about patients’ perceptions about how connected these data are with their health.

The connection between many of these data sources to health is often obvious and many of those health connections were frequently recognized by study participants. And yet, regulations protecting the privacy of health information are defined not by health-relatedness, but by information source [23]. Health-related information arising in the context of clinical care is highly protected under the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Health-related information arising in the context of consumer purchases or social media use is not. And yet in some cases that latter was perceived as more health related than the former.

The emergence of direct-to-consumer genetic testing sites like 23andMe [24,25,26] can reveal predictive or suggestive information to patients that they may or may not want to know. For example, when considering feedback from genetic research, 87% of participants agree that they would want to have findings shared with them if researchers found that they had a genetic pattern linked to a life threatening condition, which was manageable or curable, 73% if the condition was not life threatening, and 72% if the condition was life threatening but not curable [27]. We found similar percentages when we asked survey respondents if they would want to know if patterns in their digital data indicate that they had a higher than average risk for a treatable disease (85%). When asked if patterns in their data indicated that they had a higher than average risk for a non-treatable disease 75% would want to know, and if patterns in their data indicated that they had a lower than average risk 74% would want to know.

In April 2018, it was revealed that the firm Cambridge Analytica had accessed the data of more than 80 million individuals’ Facebook accounts without their permission. The public response was considerable, with many concerns raised about data privacy and what companies know about individuals and the types of information they share online. This type of large-scale privacy violation has an impact on the trust people have in the security of their digital data, and some people reportedly deleted their social media accounts after this occurred [28]. Of note, a large proportion (74%) of patients surveyed in this study had expressed concern that companies might share information with third parties without consent, a full 6-months before the Cambridge Analytica activities were reported in the media.

As researchers gain greater insight into the relationship between online activity and an individual’s health, transparency of these findings is essential to maintain trust. Increasing focus on returning research findings to patients is evident in the digital era where there is a movement toward open science and better patient engagement [29].

A better understanding specifically of health-related digital footprints is important for being able to provide guidance to patients about their use of digital platforms and sharing practices. This emerging field is in its infancy as many of the most popular social media and online sites have only been available for slightly more than ten years.

While providing data back to patients would be a first step, future work would also focus on the utility of this data being provided to healthcare providers via an EMR. Less defined is how this data would be interpreted, or used, or if it would even be welcomed. Regular reports of patients’ steps walked, calories consumed, Facebook status updates, and online footprints might create overwhelming expectations of regular surveillance of questionable value and frustratingly limited opportunities to intervene even if strong signals of abnormal patterns were detected [30]. This future work could assess healthcare providers use of digital data incorporated in an EMR and focus on issues related to the accuracy, interpretability, meaning, and actionability of the data [31,32,33,34,35].

This study has limitations. The findings are exploratory and represent a small sample size from a non-representative population. Response rate may have been influenced by patients being queried in a medical environment and could vary if patients were asked in non-hospital settings. This study also has strengths. Because we told patients that we would immediately access their data should they be willing to share it, their willingness to share more likely represents true preferences, rather than merely the expressed preferences of a typical hypothetical setting.

Conclusions

Patients use a variety of digital applications that generate large amounts of data. Our work demonstrates that participants would be willing to donate some of their digital data to researchers and clinicians in pursuit of health-related insights. This work adds to the larger domain of privacy and health research by connecting various digital data with perceived health relatedness. Both the willingness to share data and the perceived relatedness of those data to health do not follow conventional divisions on which health information privacy policies are built. Future work should be directed towards understanding the contexts in which patients are most likely to donate data for research use, and how they would want insights shared with them.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the IRB guidelines but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- EFA:

-

Exploratory factor analysis

- EMR:

-

Electronic Medical Records

- GPS:

-

Global Position System

- HIPAA:

-

Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996

- IRB:

-

Institutional Review Board

References

Hill K. How target figured out a teen girl was pregnant before her father did: Forbes; 2012.

Duhigg C. How companies learn your secrets: The New York Times; 2012. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2012/02/19/magazine/shopping-habits.html

Your Rights Under HIPAA [Internet]. Health and Human Services. 2017 [cited 2019 Jun 7]. Available from: https://www.hhs.gov/hipaa/for-individuals/guidance-materials-for-consumers/index.html

Anderson, J. What will digital life look like in 2025? Highlights from our reports. Pew Research Center; 2014. Available at: https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2014/12/31/what-will-digital-life-look-like-in-2025-highlights-from-our-reports/.

Grande D, Mitra N, Shah A, Wan F, Asch DA. Public preferences about secondary uses of electronic health information. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173:1798.

Nissenbaum H. Privacy in context: Technology, policy, and the integrity of social life. Stanford: Stanford University Press; 2009.

Padrez KA, et al. Linking social media and medical record data: a study of adults presenting to an academic, urban emergency department. BMJ Qual Saf. 2016;25:414–23.

Fox S, Jones S. The Social Life of Health Information, Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project; 2011.

Doherty C, Lang M. An Exploratory Survey of the Effects of Perceived Control and Perceived Risk on Information Privacy. In: 9th Annual Symposium on Information Assurance; 2014.

Horn JL. A rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika. 1965;30:179–85.

Hayton JC, Allen DG, Scarpello V. Factor retention decisions in exploratory factor analysis: a tutorial on parallel analysis. Organ Res Methods. 2004;7:191–205.

Adler NE, et al. Socioeconomic status and health: the challenge of the gradient. Am Psychol. 1994;49:15–24.

Wong CA, Hernandez AF, Califf RM. Return of research results to study participants. JAMA. 2018;320:435.

Barnaghi P, Sheth A, Henson C. From data to actionable knowledge: big data challenges in the web of things [guest editors’ introduction]. IEEE Intell Syst. 2013;28:6–11.

Horvitz E, Mulligan D. Policy forum. Data, privacy, and the greater good. Science. 2015;349:253–5.

Eichstaedt JC, et al. Facebook language predicts depression in medical records. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1802331115.

Guntuku SC, Yaden DB, Kern ML, Ungar LH, Eichstaedt JC. Detecting depression and mental illness on social media: an integrative review. Curr Opin Behav Sci. 2017;18:43–9.

Guntuku SC, Ramsay JR, Merchant RM, Ungar LH. Language of ADHD in adults on social media. J Atten Disord. 2017. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1087054717738083.

Merolli M, Gray K, Martin-Sanchez F. Health outcomes and related effects of using social media in chronic disease management: a literature review and analysis of affordances. J Biomed Inform. 2013;46:957–69.

Salathé M, et al. Digital epidemiology. PLoS Comput Biol. 2012;8.

Wicks P, et al. Sharing health data for better outcomes on PatientsLikeMe. J Med Internet Res. 2010;12:e19.

Coppersmith G, Leary R, Crutchley P, Fine A. Natural language processing of social media as screening for suicide risk. Biomed Inform Insights. 2018;10:117822261879286.

Office for Civil Rights, HHS. Standards for privacy of individually identifiable health information. Final rule. Fed Regist. 2002;67:53181–273.

Zettler PJ, Sherkow JS, Greely HT. 23andMe, the Food and Drug Administration, and the future of genetic testing. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:493.

Annas GJ, Elias S. 23andMe and the FDA. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:985–8.

Kalf RRJ, et al. Variations in predicted risks in personal genome testing for common complex diseases. Genet Med. 2014;16:85–91.

Assessing public attitudes to health related findings in research: Medical Research Council and Wellcome Trust. 2012. Available at: https://wellcome.ac.uk/sites/default/files/wtvm055196_0.pdf.

DeGroot JM, Vik TA. “We were not prepared to tell people yet”: confidentiality breaches and boundary turbulence on Facebook. Comput Human Behav. 2017;70:351–9.

Wong CA, Hernandez AF, Califf RM. Return of research results to study participants: uncharted and untested. JAMA. 2018;320:435-6.

Padrez KA, Asch DA, Merchant RM. The patient diarist in the digital age. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30:708-9.

Chen C, Haddad D, Selsky J, et al. Making sense of mobile health data: an open architecture to improve individual- and population-level health. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(4):e112.

Lupton D. The digitally engaged patient: self-monitoring and self-care in the digital health era. Soc Theory Health. 2013;11:256–70.

Estabrooks PA, Boyle M, Emmons KM, et al. Harmonized patient-reported data elements in the electronic health record: supporting meaningful use by primary care action on health behaviors and key psychosocial factors. JAMIA. 2012;19(4):575–82.

Brennan PF, Downs S, Casper G. Project HealthDesign: rethinking the power and potential of personal health records. J Biomed Inform. 2010;43(5 Suppl):S3–5.

Brennan PF, Casper G, Downs S, Aulahk V. Project HealthDesign: enhancing action through information. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2009;146:214–8.

Acknowledgements

We thank research assistants Janice Lau, Molly Casey, and Justine Marks for their assistance with data collection. We also thank the patients for sharing their responses to the survey.

Funding

This project was supported by a Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Pioneer Award (72695). No sponsor of funding source played a role in: “study design and the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and the writing of the article and the decision to submit it for publication.” All researchers are independent from funders.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ES, JG, and RMM originated the study. ES, JG, SCG, DG, DA, and RMM developed methods, interpreted analysis, and contributed to the writing of the article. EK, DG, DA, SCG, and RMM assisted with the interpretation of the findings and contributed to the writing of the article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Review Board (#827652). A written consent was obtained from the participants.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Survey Questionnaire. (DOCX 35 kb)

Additional file 2:

Figure S1. Patients Reporting Data Usage/Access. This figure shows the percentage of patients who reported using the indicated devices or accessing the type of data listed. (DOCX 74 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Seltzer, E., Goldshear, J., Guntuku, S.C. et al. Patients’ willingness to share digital health and non-health data for research: a cross-sectional study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 19, 157 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-019-0886-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-019-0886-9