Abstract

Background

Electronic medical record systems are being implemented in many countries to support healthcare services. However, its adoption rate remains low, especially in developing countries due to technological, financial, and organizational factors. There is lack of solid evidence and empirical research regarding the pre implementation readiness of healthcare providers. The aim of this study is to assess health professionals’ readiness and to identify factors that affect the acceptance and use of electronic medical recording system in the pre implementation phase at hospitals of North Gondar Zone, Ethiopia.

Methods

An institution based cross-sectional quantitative study was conducted on 606 study participants from January to July 2013 at 3 hospitals in northwest Ethiopia. A pretested self-administered questionnaire was used to collect the required data. The data were entered using the Epi-Info version 3.5.1 software and analyzed using SPSS version 16 software. Descriptive statistics, bi-variate, and multi-variate logistic regression analyses were used to describe the study objectives and assess the determinants of health professionals’ readiness for the system. Odds ratio at 95% CI was used to describe the association between the study and the outcome variables.

Results

Out of 606 study participants only 328 (54.1%) were found ready to use the electronic medical recording system according to our criteria assessment. The majority of the study participants, 432 (71.3%) and 331(54.6%) had good knowledge and attitude for EMR system, respectively. Gender (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI: [1.26, 2.78]), attitude (AOR = 1.56, 95% CI: [1.03, 2.49]), knowledge (AOR = 2.12, 95% CI: [1.32, 3.56]), and computer literacy (AOR =1.64, 95% CI: [0.99, 2.68]) were significantly associated with the readiness for EMR system.

Conclusions

In this study, the overall health professionals’ readiness for electronic medical record system and utilization was 54.1% and 46.5%, respectively. Gender, knowledge, attitude, and computer related skills were the determinants of the presence of a relatively low readiness and utilization of the system. Increasing awareness, knowledge, and skills of healthcare professionals on EMR system before system implementation is necessary to increase its adoption.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

With the advance of information communication technologies (ICTs) in the last 20 years, different systems are being implemented in healthcare organizations to improve healthcare services with better data management, communication, and decision making. Out of these, implementing the Electronic Medical Record (EMR) System is the priority agenda not only in developed countries but also in many developing countries [1]. The national e-health strategy toolkit developed by WHO and ITU [2] defines EMR as “a computerized medical record used to capture, store, and share information among healthcare providers in an organization, supporting the delivery of health services to patients”. EMR is perceived as a way to improve healthcare quality through improving work flow, reducing medical errors, minimizing cost and treatment time, increasing revenue, improving patient care by creating a better linkage to all care givers, reducing the need for file space, supplies, and workers for the retrieval and filing of medical records [3]-[5].

Even though there is a high expectation for and interest in EMR as great potential for improving quality, continuity, safety, and efficiency in healthcare worldwide, the overall adoption rate is relatively low [6]-[8]. More than 50.0% of the EMRs either fail or fail to be properly utilized in the world [7],[9].

The key causes for the low EMR adoption are not only the challenges that follow implementation but also the lack of pre implementation activities, like resource and organizational readiness [10]-[12] which can facilitate the success of the system implementation. However, only a few studies have been conducted or reported on the readiness of health professionals prior to the actual system implementation. For developing countries, the World Health Organization (WHO) had developed a manual [13] which outlines the preliminary necessary issues, such as organizational, technical, infrastructural, and health professionals readiness for a new work practice of EMR. Nevertheless, most pre implementation assessments failed to include the health professionals’ knowledge and attitude (readiness) which might be a determining factor for the success of the implemented EMR System.

The electronic medical record readiness assessment, as part of a pre implementation assessment is considered essential and must include the human factors [14]. Readiness assessment aims to evaluate the preparedness of each organizational component for a new system implementation [11]. Therefore, identifying areas and requirements before the implementation will help to identify the areas of focus which need to be done during implementation.

One major barrier to successfully implement an EMR system reported by many studies [15]-[19] is whether clinicians accept the new system and the potential disruptions and changes that follow. It has been suggested that health workers perceived EMR as interfering with clinical workflow, reducing productivity, and introducing disruptive changes to the workplace. This tendency is much more serious in developing countries where computer anxiety is very high [20].

In the Fourth Health Sector Development Plan, the Ethiopian Government had insisted that EMR must be implemented at the major hospitals. The Ministry of Health in collaboration with Tulane University Technical Assistance Project in Ethiopia (TUTAPE) developed a comprehensive EMR system called SmartCare. So far, the system has been deployed in more than eleven hospitals and clinics in Diredawa, Bahirdar, Harar, and Addis Ababa city administrations of Ethiopia as a pilot, and the Ministry of Health planned to scale it up to other hospitals and regions [21].

In its pilot implementation phase, user resistance was reported to be the primary hindering factor to its successful adaptation. Therefore, it is essential to assess the level of readiness of health professionals in front line hospitals and determine the measures to be taken during the implementation of the system in the months ahead. In Ethiopia, no study assessed the readiness and attitude of health professionals for computerization during a pre implementation phase. This study therefore aimed to determine the readiness of health professionals for EMR system implementation, use, and associated developments in hospitals in northwest Ethiopia, which are only months away from the implementation of EMR system. The findings of this study will serve North Gondar Zone, the Amhara Regional Health Bureau, the hospitals under study, health professionals, and hospitals in other similar settings as important evidence to plan and make interventions.

Methods

An institutional based cross-sectional quantitative study was carried out from January to July 2013 at three hospitals in the northern part of Ethiopia. The study was conducted in North Gondar Zone, northwest Ethiopia. Within the zone, there are three hospitals, named Metema, Debark, and University of Gondar Hospitals. Metema and Debark Hospitals are district hospitals and University of Gondar Hospital is a specialized referral hospital that serves a catchment area of more than 2 million people. In the three hospitals, there is EMR system called the SmartCare Software operating only in the patient registration department with a plan of expanding it to other main clinical departments. Currently, the system is used only to register patients’ socio demographic and some clinical data at the triage level. It also allows users to quickly identify and locate patient history cards. Provision for the use of the International Classification of Diseases, version 10 (ICD-10) is included in the EMR system but is utilized only by the department of Antiretroviral Therapy, not by outpatient, pharmacy, and radiology departments. The latter two are not linked and computerized. In the ART Department, there is a special purpose software designed to register ART related data. Unlike Debark and Metema Hospitals, the Laboratory Department of University of Gondar Hospital is automated with laboratory software used to register laboratory requests and results.

No interoperability and standards are currently used in the three hospitals. Individual identification is being given sequentially while there are no facility codes as the facilities are identified by names.

All the 606 health professionals who were working in the three hospitals (496 at University of Gondar Hospital, 52 at Debark Hospital, and 58 at Metema Hospital) were included in the study for higher precision and accuracy.

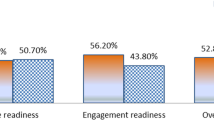

Core Readiness is defined as the realization of needs and expressed dissatisfaction with the current way of working while Engagement Readiness is defined as active willingness and participation of people for EMR implementation. We defined Overall readiness as the intersection of core readiness and engagement readiness. That is, health professional is said to have overall readiness he or she must have both engagement readiness and core readiness [22]. We determined core readiness by the different difficulties they face in their current working practice. If health professionals mark at least two problems, like inefficient documentation of patient records, dissatisfaction with the completeness and accuracy of patient data, as well as difficulty in sharing patient records in the questionnaire we assumed they have core readiness for EMR system. We measured the engagement readiness of health professional in terms of their fear or concern about the potentially negative impacts, their recognition of the benefits of EMR, and their willingness to accept EMR training. Both core and engagement readiness were measured by a set of four questions each, and participants who scored more than the mean were categorized as ready and less than the mean were categorized as not ready. Both Core and engagement readiness help people weigh the advantages and disadvantages of the new system in terms of their personal contexts, assess the risk, and question EMR as a solution. The questions regarding core and engagement readiness were validated and used in different studies of EMR and telehealth projects [23]-[26].

Based on the above framework, participants were asked to measure their current knowledge, attitude, and current utilization of the EMR system (if any, for example, University of Gondar Hospital has standalone EMR system in the laboratory department) as well as their core and engagement readiness levels. Attitude was defined as user feelings about the EMR system if implemented, and knowledge was defined as levels of existing knowhow about the EMR systems. Both attitude and knowledge were measured by a set of four questions each, and participants who obtained more than the mean score were categorized as good and those who scored less than the mean were categorized as poor. Professionals who answered more than 50% of the knowledge, attitude, and readiness questions were classified as good and those who scored less than 50% were classified as poor.

A structured self-administered questionnaire was prepared based on the WHO EMR readiness evaluation framework and additional literature [10]-[12]. The questionnaire comprised of socio demographic, behavioral (knowledge and attitude), technical, and organizational variables. It was prepared in English, translated into Amharic (local language), and then back to English to check its consistency. The tool was pretested on a group of 30 health professionals who did not belong to the study hospitals. The necessary corrections were made on the questionnaire based on the pretest results.

Six data collectors and two supervisors participated in the data collection process. One day training was given to the data collectors and supervisors on the objective of the study and data collection procedures. The principal investigator and supervisors did a daily supportive supervision on data collectors. Data back-up activities, like storing data at different places and putting data in different formats (hard and soft copies) were performed to prevent data loss.

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained from the Institutional Ethical Review Board of the University of Gondar, Ethiopia. Written consents were taken from the administrations of the respective hospitals. Informed verbal consent was also obtained from individual study participants after an explanation of the study objectives and data confidentiality issues.

The principal investigator and supervisors did frequent data editing manually. Epi Info version 3.5.1 and SPSS version16 were used to enter and analyze data, respectively. Manually edited data were entered into the computer using the data entry template created on Epi Info version 3.5.1 for further analysis. Then the data were exported and analyzed using SPSS version 16. Descriptive statistics was computed to describe the study objectives in terms of appropriate variables. Binary and multi-vitiate logistic regression analysis were carried out to identify the most important variables which could determine EMR readiness and use of health professionals in the study area. Variables with a p-value of ≤ 0.2 on binary logistic regression analysis were entered and further computed on the multi-variate logistic regression model. Associations between the study and outcome variables were described using odds ratio at 95% CI.

Results

Socio demographic characteristics

A total of 606 health professionals participated in the study. Of the respondents, 496 (81.8%), were from the University of Gondar Hospital. The mean standard deviation age of the respondents was 26.73 ± 3.99 years with a range of 21 to 50 years. The majority (83.8%) of the study participants were in the age range of 21-29 years (Table 1).

Regarding educational status, 439 (72.4%), of the health professionals had a bachelor’s degree and above, while 167 (27.6%) had diploma and certificate. One hundred fifty-five (25.6%) of the study participants had been working in the study area for less than two years. 187 (30.9%), 133 (21.9%), and 131 (21.6%) of the respondents had working experiences of two to three years, three to five years, and more than five years, respectively. Out of all participants, 319 (52.6%), were nurses, 84 (13.9%) laboratory technicians, 46 (7.6%) pharmacists, and 43 (7.1%) were midwives by profession. More than half, 356 (58.7%), of the respondents were computer literate and 204 (36.7%) had computer access at home.

Readiness and utilization of health professionals towards EMRs

From the total participants, 328 (54.1%) had overall readiness towards EMR with 411(67.8%) demonstrating core readiness and 369(60.9%) demonstrating engagement readiness towards EMR. The overall existing EMR utilization in the study area was 282 (46.5%) (Figure 1).

Knowledge and attitude of health professionals for EMR

The majority of the study participants, 432 (71.3%), and 331(54.6%) had good knowledge of and attitude to EMR system, respectively. About 582(96.0%) of the respondents did not have any knowhow about EMR system. The majority, 566 (93.4%), 544 (89.8%), and 544 (89.8%) of the participants said that the hospitals had no good infrastructure; or computers and related technologies; and that they did not have computer related skills, respectively. 540 (89.1%) of the health professionals knew that EMR had great importance for the healthcare system (Table 2).

Factors associated with health professionals’ readiness for EMR system

In this study, variables like gender, age, good knowledge, having good attitude, willingness to implement EMR system, computer literacy, computer related skills, availability of computers in working place and home, past information technology experience, training access, complexity of system, and level of experience were positively associated with the readiness and use of EMRs by health professionals.

Male health professionals were 1.87 times more likely to be ready for EMR system than female health professionals (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI: [1.26, 2.78]). Similarly, study participants who had good knowledge on EMR system were about 2.12 times more likely to get ready for EMR system as compared to those health professionals with poor knowledge (AOR = 1.87, 95% CI: [1.32, 3.52]). Health professionals who were willing to implement EMR system were 2.63 times more likely to be ready for EMR system than their counterparts (AOR = 2.63, 95% CI: [1.45, 4.78]). Respondents with previous IT experience were 1.69 [1.12, 2.34] times more ready to use EMR system compared with their counter parts (Table 3).

Discussion

The present study assessed the readiness of health professionals in three hospitals that were in the frontline to implement the EMR system in the coming years. In our assessment, the overall readiness of those health professionals for an EMR system was 54.1% (with 67.8% core and 60.9% engagement readiness) and can be regarded as low. As health professionals are the main actors in the adaptation and sustainability of the system, interventions are needed in building attitude on the EMR systems. A similar study conducted in Afghanistan (Kabul and Bamyan) on health needs and ehealth readiness assessments of healthcare organizations also found that core readiness for EMR system was 66.7% in Byaman. The result is similar to that of the current study (67.8%) but lower than that in Kabul (35.5%) [27].

The result revealed that health professionals aged 30-34 years were 52% less likely to be ready for EMR system than younger health professionals (AOR = 0.48, (95% CI): 0.24, 0.94). A study conducted in Kuwait also indicated that younger health professionals had better readiness for EMR system [28]. This may be due to the fact that younger people natural tend to have more motive, interest, and readiness to accept new technology developments than aged people.

This study showed that health professionals who were willing to accept the implementation of EMR system were 2.63 times more likely to be ready for EMR system (AOR = 2.63, (95% CI): 1.45, 4.78). Those who had good attitude were 1.56 times more likely to have readiness for EMR system as compared to those health professionals who had poor attitude (AOR = 1.56, (95% CI): 1.03, 2.49). This may be so because favoring the implementation of EMR system may influence the readiness for the system. As discussed in many other studies [6],[9],[29] health professionals who have good attitude about computerization are more likely to adapt the system. This is also a good explanation for the need to create awareness about EMR system before implementation in order to engage professionals during the system implementation so that they will have good attitude and develop their readiness for a better adaptation of the system.

The present study also identified that health professionals who had good knowledge on EMR system were about 2.12 times more likely to be ready for EMR system as compared to health professionals with poor knowledge (AOR = 2.12, (95% CI): 1.32, 3.56). This may be due to the fact that health professionals who have good knowledge may have the tendency to accept the advantage of technology and to be likely to be ready for EMR system.

The present study also revealed that health professionals who were computer literate, current computer users, and had computers at work place were about 1.64 (AOR = 1.64, (95% CI): 0.99, 2.68), 2.55 (AOR = (2.55, (95% CI):1.62, 3.76), and 1.78 (AOR = 1.78, (95% CI):1.15, 2.77) times more likely to be ready than their counter parts, respectively. A similar study conducted on implementing EMR system in developing countries showed that poor computer skills of healthcare professionals was highly related with poor readiness for EMR system [9],[14],[25],[30],[31]. The possible reason for this could be that being computer literate and the availability of computer had a direct influence on health professionals’ views on computer based system use.

This study also showed that health professionals who believed that there was good technical infrastructure for EMR system were 1.78 (AOR = 1.78, (95% CI): 1.01, 3.17) times more likely to be ready for EMR system. This result is comparable to previous systematic reviews conducted on the barriers to the acceptance of EMR system [17]. This particular result is good evidence of the need to discus and promotes EMRs to health professionals before implementation. Just showing the server and the computer infrastructure available for the implementation, can build the confidence of professionals in the success of the implemented system.

From this study, we found out that knowledge and readiness for a computer-based system was relatively low. This can be attributed to the overall technological culture of the society where computer and ICT use is very low and needs more awareness creation before the actual EMR implementation.

Conclusion

The overall readiness of health professional for EMR system in the study areas was 54.1%. The core and engagement readiness of the study participants were 67.8% and 60.9%, respectively.

Gender, age, computer literacy, knowledge, good attitude, computer related skills, availability of computer in working place and home, past information technology experience, training access, and complexity of the system were the most determinant factors for readiness of health care professionals for EMR system. In addition to training on how to use EMR system and purchasing computers, EMR system implementers need prior discussion and promotion of EMR systems to the potential primary users to increase its adaption and success rate.

References

Azubuike MC, Ehiri JE: Health information systems in developing countries: benefits, problems, and prospects. J R Soc Promot Health. 1999, 119 (3): 180-184. 10.1177/146642409911900309.

Hamilton C: The WHO-ITU national eHealth strategy toolkit as an effective approach to national strategy development and implementation. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013, 192: 913-916.

Kalogriopoulos NA, Baran J, Nimunkar AJ, Webster JG: Electronic medical record systems for developing countries: Review. Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society, 2009 EMBC 2009 Annual International Conference of the IEEE: 3-6 Sept. 2009 2009. 2009, IEEE, Minneapolis, MN, 1730-1733. 10.1109/IEMBS.2009.5333561.

Bagayoko CO, Anne A, Fieschi M, Geissbuhler A: Can ICTs contribute to the efficiency and provide equitable access to the health care system in Sub-Saharan Africa? The Mali experience. Yearb Med Inform. 2011, 6 (1): 33-38.

Williams F, Boren SA: The role of the electronic medical record (EMR) in care delivery development in developing countries: a systematic review. Inform Prim Care. 2008, 16 (2): 139-145.

Terry AL, Brown JB, Bestard Denomme L, Thind A, Stewart M: Perspectives on electronic medical record implementation after two years of use in primary health care practice. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012, 25 (4): 522-527. 10.3122/jabfm.2012.04.110089.

Willyard C: Focus on electronic health records: electronic records pose dilemma in developing countries. Nat Med. 2010, 16 (3): 249-10.1038/nm0310-249a.

Miller RH, Sim I: Physicians’ use of electronic medical records: barriers and solutions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2004, 23 (2): 116-126. 10.1377/hlthaff.23.2.116.

Ketikidis P, Dimitrovski T, Lazuras L, Bath PA: Acceptance of health information technology in health professionals: an application of the revised technology acceptance model. Health Informatics J. 2012, 18 (2): 124-134. 10.1177/1460458211435425.

Ghazisaeidi M, Ahmadi M, Sadoughi F, Safdari R: A roadmap to pre-implementation of electronic health record: the key step to success. Acta Inform Med. 2014, 22 (2): 133-138. 10.5455/aim.2014.22.133-138.

Lorenzi NM, Kouroubali A, Detmer DE, Bloomrosen M: How to successfully select and implement electronic health records (EHR) in small ambulatory practice settings. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2009, 9 (1): 15-10.1186/1472-6947-9-15.

Ginsberg D: Successful Preparation and Implementation of an Electronic Health Records System. Best Practices: A guide for improving the efficiency and quality of your practice. 2011, California Medical Association, California

World Health Organization: Electronic Health Records: Manual for Developing Countries. 2006, WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific, Manila, Philippines

Kuo KM, Liu CF, Ma CC: An investigation of the effect of nurses’ technology readiness on the acceptance of mobile electronic medical record systems. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013, 13 (1): 88-10.1186/1472-6947-13-88.

Al-Aswad AM, Brownsell S, Palmer R, Nichol JP: A review paper of the current status of electronic health records adoption worldwide: the gap between developed and developing countries. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2013, 7 (2): 153-164.

Anwar F, Shamim A, Khan S: Barriers in adoption of health information technology in developing societies. Int J Adv Comput Sci Appl. 2011, 2: 40-45.

Boonstra A, Broekhuis M: Barriers to the acceptance of electronic medical records by physicians from systematic review to taxonomy and interventions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2010, 10 (1): 231-10.1186/1472-6963-10-231.

Cherry B, Ford EW, Peterson LT: Long-Term Care Facilities Adoption of Electronic Health Record Technology: A Qualitative Assessment of Early Adopters’ Experiences. In. 2009, Texas Tech University, Texas

Herbst K, Littlejohns P, Rawlinson J, Collinson M, Wyatt JC: Evaluating computerized health information systems: hardware, software and human ware: experiences from the Northern Province, South Africa. J Public Health Med. 1999, 21 (3): 305-310. 10.1093/pubmed/21.3.305.

Gamm LD, Barsukiewicz CK, Dansky KH, Vasey JJ, Bisordi JE, Thompson PC: Pre- and post-control model research on end-users' satisfaction with an electronic medical record: preliminary results. Proceedings of the AMIA Symposium. 1998, American Medical Informatics Association, Pennsylvania,United States, PMC2232071: 225-229

Lemma W, Tesfaye H: Electronic Health Management Information, SmartCare In Ethiopia In: 2011 Public Health Informatics Conference 21 - 24 August 2011 2011; Atlanta, GA. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (recorded computer demonstration). https://cdc.confex.com/cdc/phi2011/webprogram/paper28729.html [accessed 3 October 2014]

Li J, Land LPW, Ray P, Chattopadhyaya S: E-Health readiness framework from Electronic Health Records perspective. Int J Internet Enterprise Manag. 2010, 6 (4): 326-348. 10.1504/IJIEM.2010.035626.

Ajami S, Ketabi S, Isfahani SS, Heidari A: Readiness assessment of electronic health records implementation. Acta Inform Med. 2011, 19 (4): 224-227. 10.5455/aim.2011.19.224-227.

Adjorlolo S, Ellingsen G: Readiness assessment for implementation of electronic patient record in Ghana: a case of university of Ghana hospital. J Health Inform Dev Ctries. 2013, 7 (2): 128-140.

Kgasi MR, Kalema BM: Assessment E-health readiness for rural South African areas. Journal of Industrial and Intelligent Information. 2014, 2 (2): 131-135. 10.12720/jiii.2.2.131-135.

Legare E, Vincent C, Lehoux P, Anderson D, Kairy D, Gagnon MP, Jennett P: Telehealth readiness assessment tools. J Telemed Telecare. 2010, 16 (3): 107-109. 10.1258/jtt.2009.009004.

Durrani H, Khoja S, Naseem A, Scott RE, Gul A, Jan R: Health needs and eHealth readiness assessment of health care organizations in Kabul and Bamyan, Afghanistan. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal = La Revue de Sante de la Mediterranee Orientale. 2012, 18 (6): 663-670.

Al-Azmi SF, Saleh KAA, Ojayan OAA: Physicians’ perceptions about the newly implemented electronic medical records systems at the primary health care centers in kuwait. Alex J Med. 2008, 44 (1): 303-312.

Jennett P, Jackson A, Ho K, Healy T, Kazanjian A, Woollard R, Haydt S, Bates J: The essence of telehealth readiness in rural communities: an organizational perspective. Telemed J E Health. 2005, 11 (2): 137-145. 10.1089/tmj.2005.11.137.

Yogeswaran P, Wright G: EHR implementation in South Africa: how do we get it right?. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2010, 160 (Pt 1): 396-400.

Fraser HS, Biondich P, Moodley D, Choi S, Mamlin BW, Szolovits P: Implementing electronic medical record systems in developing countries. Inform Prim Care. 2005, 13 (2): 83-95.

Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to the University of Gondar for the approval of the ethical clearance and its technical and financial support. We would like to extend our heartfelt thanks to North Gondar Zone Health Department and the local administration of Debark, Metema, and University of Gondar Hospital for their kind collaboration. Authors are also highly indebted to data collectors and study participants.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

SB, TY, and MA contributed during the process of proposal development. SB handled the data collection process. SB, TY, MA, and BT involved during data analysis and write up. BT prepared the draft. Then SB, TY, and MA revised drafts of the paper. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Biruk, S., Yilma, T., Andualem, M. et al. Health Professionals’ readiness to implement electronic medical record system at three hospitals in Ethiopia: a cross sectional study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 14, 115 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-014-0115-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-014-0115-5