Abstract

Background

Biobanking biospecimens and consent are common practice in paediatric research. We need to explore children and young people’s (CYP) knowledge and perspectives around the use of and consent to biobanking. This will ensure meaningful informed consent can be obtained and improve current consent procedures.

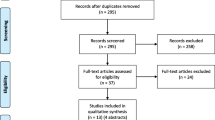

Methods

We designed a survey, in co-production with CYP, collecting demographic data, views on biobanking, and consent using three scenarios: 1) prospective consent, 2) deferred consent, and 3) reconsent and assent at age of capacity. The survey was disseminated via the Young Person’s Advisory Group North England (YPAGne) and participating CYP’s secondary schools. Data were analysed using a qualitative thematic approach by three independent reviewers (including CYP) to identify common themes. Data triangulation occurred independently by a fourth reviewer.

Results

One hundred two CYP completed the survey. Most were between 16–18 years (63.7%, N = 65) and female (66.7%, N = 68). 72.3% had no prior knowledge of biobanking (N = 73).

Acceptability of prospective consent for biobanking was high (91.2%, N = 93) with common themes: ‘altruism’, ‘potential benefits outweigh individual risk’, 'frugality', and ‘(in)convenience’.

Deferred consent was also deemed acceptable in the large majority (84.3%, N = 86), with common themes: ‘altruism’, ‘body integrity’ and ‘sample frugality’. 76.5% preferred to reconsent when cognitively mature enough to give assent (N = 78), even if parental consent was previously in place. 79.2% wanted to be informed if their biobanked biospecimen is reused (N = 80).

Conclusion

Prospective and deferred consent acceptability for biobanking is high among CYP in the UK. Altruism, frugality, body integrity, and privacy are the most important themes. Clear communication and justification are paramount to obtain consent. Any CYP with capacity should be part of the consenting procedure, if possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles, news and stories from top researchers in related subjects.Introduction

Biobanking has become increasingly common, in biomedical research, and within in paediatrics [1, 2]. Biobanks are valuable repositories of human biospecimens, associated data and technological infrastructure [3]. Biobanks provide an important resource for biomedical research in the development of new diagnostic methods, treatments, determinants of disease in various contexts.

The success of a biobank relies on the willingness of people to donate samples, and incurs many ethical, social and legal challenges. Biobanking raises unique issues with regards to consenting procedures, sample donation, data confidentiality and privacy [4,5,6]. There is little guidance around the ethics of biobanking, however the Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences (CIOMS) has published guidelines [7], addressing issues around collection, storage, and use of biological materials and related data in health-related research. They provide general and specific considerations for biobanks, including governance for keeping participants informed of research outcomes, consent, withdrawal of consent and opt out procedures, and unexpected or unsolicited findings alongside the storage and use of genetic material. Ashcroft and Macpherson [6] identified further ethical concerns including “misconceptions about biobanking and distinctions between research, diagnostics, and treatment; unknown consequences of, and harms to, individual and collective donors of materials or information and socioeconomic inequities that impinge on donor understanding and voluntariness and increase their vulnerabilities to harms and wrongs”. The complex nature of obtaining informed consent in diverse cultural and socioeconomic context, especially during public health emergencies is particularly difficult. Whilst these issues are under ethical debate, there is currently no definite consensus opinion, especially for children and young persons [8]. Children and, to a lesser extent, young persons lack the capacity to consent, therefore, the ethical consensus in adult research cannot be extrapolated to paediatrics. The Mental Capacity Act [9] applies to children who are 16 years and over. “Mental capacity is present if a person can understand information given to them, retain the information given to them long enough to make a decision, can weigh up the advantages and disadvantages of the proposed course of treatment in order to make a decision, and can communicate their decision.” [9, 10]. Once a young person is sixteen years old, they are deemed competent to consent or refuse treatment and their parents cannot override them. For children under sixteen years of age the Act does not apply and they need to be assessed for ‘Gillick competence’. This a term used in law to decide if a child is competent to consent for their own medical treatment, without parental permission or knowledge Parents cannot override a competent child’s refusal to accept treatment. Gillick competency is a professional assessment and there is no set of defined questions [11]. It is often used in a wider context to help assess whether a child has the maturity to make their own decisions and to understand the implications of those decisions.

Prospective consent is the golden standard of consent. As children cannot legally consent, this is sought from parents or their legal guardian [8]. Obtaining assent from the child or young person (CYP) is deemed best clinical practice.

In 2008 the United Kingdom (UK) amended legislation allowing deferred consent for research in an emergency setting [12]. Collecting samples in an emergency allows increased access to quality samples (for example before treatments are given) but also allows samples to be taken at the same time as clinically necessary tests which reduces the number of potentially invasive or painful tests (blood sampling) and the distress that can cause for CYP.

Deferred consent addresses difficulties encountered whilst conducting research in emergency settings [13], mainly those related to time constraints for sample collection and parental capacity in a stressful setting [14, 15]. Others argue deferred consent interferes with core values of informed consent, represents a dishonest attempt to justify recruitment without consent, and compromises autonomy [14].

Further ethical issues involve reconsent. As children grow up, most children developmentally move from minimal to robust autonomy in adolescence, and develop the capacity to consent [16]. Biobanked samples might be stored and used for decades, by which time the CYP will have developed capacity, and may have new insights regarding use of their donated samples and associated personal data [4]. This suggests that reconsent may be necessary to justify use of the samples beyond childhood.

Although aforementioned ethical issues are under debate, the literature mainly focuses on the theoretical debate [4, 17, 18] or involves perspectives of parents or legal guardians [5, 19, 20], practitioners [15], the critically ill [14, 21] or adolescents already participating in research involving biobanks [22, 23]. Perspectives of the general population mainly involves adults, with university students being closest to the paediatric population [24, 25]. Literature on the CYP’s perspective is surprisingly sparse, despite being fundamental to the ongoing ethical debate.

This study aimed to assess CYP perspectives in the community towards prospective consent, deferred consent, reconsent and assent for biobanked samples. Secondary, we investigated views on sample donation, donation hesitation and data handling.

Methods

Study design and ethics

This was a cross-sectional, qualitative survey-based study. Anonymity of participants was maintained throughout the entire study. As part of the Diagnosis and Management of Febrile Illness using RNA Personalised Molecular Signature Diagnosis (DIAMONDS) study, ethics approval was obtained for the UK under: IRAS 209035, REC 16/LO/1684. DIAMONDS aims to establish a biobank of host gene signatures of common inflammatory and infectious causes of febrile disease in children. The survey was voluntary and anonymous. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Written informed consent for the survey from parents or legal guardians was not required or obtained for patients under 16 years of age, with approval from the Newcastle and North Tyneside Research Ethics Committee. The survey was registered with our local audit registry, under audit number 13906.

Parental input was seen as a barrier to CYP participation and would potentially influence the responses. The co-produced element of the project ensured the subject and information created was CYP friendly, which significantly impacts their capacity to understand the circumstances and details of the research being proposed. The information was written and presented in a CYP friendly manner, to ensure CYP had all the information required to consent. Gillick competence was applied: reading the introductory information paragraph preceding the survey and the ability to complete the survey constituted consent for participants under the age of 16 years.

Participants

The target population were CYP attending secondary schools in the North East of England. Any CYP aged 11–21 years inclusive involved with the Young Person’s Advisory Group North England (YPAGne) was invited to complete the survey, and they recruited further CYP who were not YPAGne members from their respective secondary schools. The participants did not donate samples to the DIAMONDS study and they were specifically asked to look independently at the ethical implications of biobanking biospecimens.

Survey development

The tailored survey was designed by volunteer CYP co-opted from YPAGne together with experienced researchers. YPAGne (https://sites.google.com/nihr.ac.uk/ypagne) is an independent organisation within our hospital that exists to promote youth voice in health research and involve them in a variety of research projects from conception until the end. The co-opted CYP who designed the survey voluntarily chose to work on the biobanking project out of their own interest. The Youth Collective Engagement Coordinator (JBa), who is not medically trained, facilitates the projects, ensures impartiality and aims to maximise the CYP’s skill development through research projects. The DIAMONDS team approached YPAGne to conduct this survey project on CYP perspectives regarding biobanking.

The CYP undertook a literature review and met with independent researchers with extensive biobanking knowledge to gain more knowledge on the topic of biobanking.

Subsequently the co-opted CYP developed the hypothetical case scenarios and the survey questions, in multiple sessions. At this stage researchers in the DIAMONDS consortium were not yet involved, to ensure survey development was neutral and not affected by any potential bias induced by the research team.

A pilot was conducted, within the wider YPAGne forum, to provide feedback on the suitability and clarity of the survey. In a facilitated group session, minor semantic modifications were made in consultation with the DIAMONDS research team, and the final version of the survey approved. There were no major modifications on the content of the survey, as the research team was in agreement with the proposed survey. After some debate, a paragraph explaining what the purpose of biobank is, was added to the survey. This was felt necessary to ensure CYP in the community with no prior knowledge of biobanking could meaningfully complete the survey.

The final survey consisted of three sections, preceded by an introductory page explaining the purpose of the study, biobanking, anonymous and voluntary participation. Survey completion was regarded as agreement to participation and consent.

The first section covered demographic data. The second section included case-based questions regarding prospective consent, deferred consent, and reconsent and assent. The final section assessed attitudes towards sample donation and data confidentiality.

Data collection

The final survey (Additional File 1) was created using Google Forms (http://docs.google.com/forms/). The weblinks for the survey were distributed by CYP via their schools’ email service, YPAGne’s Facebook page, and other social media platforms such as WhatsApp, Instagram, Twitter and Snapchat. Data was collected from February to April 2021, with a second survey distribution in December 2021 to achieve data saturation.

Measures

Demographics

Participants were asked their age (in groups), self-identified gender (male, female, prefer not to say, other), partial postcodes, previous knowledge of biobanking (yes/no), and any previous hospital admission (yes/no).

Case-based consent procedures for biobanking

Case 1 revolved around prospective informed consent. We presented a case of a CYP attending for routine medical procedures and being asked to donate an extra sample for a biobank. Case 2 involved deferred consent. We described a case in which CYP had blood taken for a diagnostic test in an emergency and an extra blood sample preserved for biobanking. Consent was asked retrospectively with an option for the sample to be destroyed if consent was not given. Attitudes regarding prospective and deferred consent were measured on a 4-point scale ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Subsequently, participants were asked to explain their answer in an open-ended question.

In case 3, we explored when a parent or legal guardian consented to a CYP having a blood sample stored in a biobank for research, if the participant would want to be asked at a later age whether they would give permission for their sample to be biobanked. If they wanted this, we asked at what age, and their opinions on reconsent or assent.

Lastly, we asked if the participant felt that CYP should be involved in the consent procedure whenever possible, and why.

Sample donation and data handling

We asked what kind(s) of biospecimens participants would be comfortable with donating to a biobank if they were collected for medical or surgical procedures regardless, followed by a question about why they would not be comfortable donating any samples. We also asked participants what information they would feel comfortable with to be stored alongside their biobanked specimens, and why they might be hesitant to donate samples to a biobank. To conclude the survey, they were asked about preferences regarding being informed when their sample is used, how they want to find out and what they want to know about sample use.

Data analysis

Quantitative data from closed questions were analysed in SPSS version 27 [Armonk USA 2020].

Qualitative data from open-ended questions were analysed using a qualitative thematic approach. Three reviewers independently analysed the open questions.

The first group of reviewers consisted of two CYP working on our study (LG and JBr) with the assistance of an experienced researcher (LH). In separate meetings they explored the data identified common themes. One meeting each was dedicated to prospective consent, deferred consent, reconsent, or donation hesitation and data confidentiality. The second (FvdV) and third (EL) reviewers identified common themes on these subjects independently. The fourth reviewer (JC) triangulated the analyses from the three reviewers to enable independent reporting and data saturation [26].

Results

One hundred two CYP completed the survey. The majority of participants were female (66.7%, N = 68), from North East England and Cumbria (86.2%, N = 88), between 16–18 years old (63.7%, N = 65), and had no previous knowledge of biobanking (72.3%, N = 74). Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of the participants, and Table 2 gives an overview of quotes from participants on the different consent approaches.

Prospective consent

Most participants 91.2% (N = 93) had a positive attitude towards prospective consent for biobanking: 46 agreed and 47 strongly agreed. Of the 9 participants with negative attitudes (8.8%), only 1 strongly disagreed with prospective consent to biobanking.

Altruistic reasons for participation were frequently expressed in statements such as: “I think the research done on it will be good for future patients” and “To take [from the health care system] you should be willing to give”.

Participants indicate potential benefits of specimen donation, outweigh the risk of the additional procedure. “I would feel happy about giving an extra blood sample. I would agree to a tissue sample if it would not leave side effects or much extra scarring”.

They did voice important considerations and would not necessarily agree to donating without clear communication. Participants want to know how and what the sample is used for: “I would be content as long as it goes to a good cause” or “I’d be happy with additional samples to be taken as extra to the procedure being done given an informative explanation”. They also highlighted the importance of being given information in advance, stating “I would be fine with it, but would require a bit of time beforehand; just so I am fully aware of what I’m doing”.

The most common reasons for those less positive about biobanking were: needle phobia, perceived additional pain related to the procedure or concerns about how the sample will be used.

Deferred consent

Deferred consent was highly acceptable among participants (84.3%): 18 agreed, and 68 strongly agreed. Only five strongly disagreed with deferred consent for biobanking (4.9%).

We observed a shift in motivation with less of a focus on altruism, but more towards frugality (Table 1). Participants realise and accept, in emergency situations, samples may be taken prior to consent being obtained. The majority of participants stated opinions such as “They would not use my sample for anything until I had given consent, so the choice is still in the hands of the patient” and “I really don’t mind. If it’s an emergency situation it’s clearly inappropriate to ask at the time, so asking afterwards is fine. Again, as long as it has no effect on my care, take what you need”. Others feel more uncomfortable but would still agree: “I would be quite annoyed if they [take a sample for biobanking] without consent, but I’d also be happy for it to be used”. A few disagreed with the concept and one person stated how this impacted their autonomy and dignity: “I think deferred consent is wrong and I would definitely feel violated in this case”.

In cases where consent is refused, participants described the importance of trust and transparency regarding sample handling. “I think it is important to provide reassurance and information about how the sample will be destroyed to ensure patients who did not give consent do not need to worry about the hospital keeping the sample”.

Assent and reconsent

All participants thought CYP should be involved in the consent procedure, “Children still have rights and I think it’s important that they feel included in decisions about their own body and medical care”. Participants thought CYP should have the ‘power of veto’ over donating samples “A child's no should be able to override a parents yes. But a child's yes should require a yes from the parents as well”.

Three quarters of participants (76.5%, N = 78) wanted to be contacted at an older age to reconsent for sample use, if they had samples taken before the age of capacity but a quarter (24.5%, N = 25) did not feel they needed to be contacted again. With regards to age of reconsent, 61 participants (59.8%) stated an age range of 16–18 years to be appropriate, in line with legal age of consent “I would say when you reach an age where you can make your own medical decisions whilst understanding the consequences, 16–18.” However, there was a wide range of suggested ages from 7 to 21 years.

Sample donation and data handling

Almost all participants were comfortable donating blood (97.1%, N = 99) and urine (89.2%, N = 91) (Fig. 1). Participants felt the main reasons CYP might hesitate to donate samples were privacy (55.6%, N = 40/72) “People might worry about their personal data being lost or stolen.”, personal views (37.5%, N = 27/72) e.g. “[I] don’t like the idea of my tissue being kept and used for long period of time and not knowing what it is used for” and embarrassment “Donating faeces can make many people feel uncomfortable” and ethical views (23.6%, N = 17/72): “I would only donate samples if I knew exactly how they would be used, in line with my own personal views.”

If CYP donate biospecimens to a biobank, the majority of participants agree that medical details could be stored alongside the sample (82.2%, N = 83). They acknowledge that their donated samples were more valuable when linked to additional clinical data, “The information will help make the sample more useful so I would be happy providing extra details”.

The minority who had reservations about additional information being stored, would be satisfied if data is stored without personal identifiers. “There should be absolutely no identifying information, or any information that is not strictly related to you [sic] biological medical record” and “as long as the government doesn't make blood-tracing nanobots that could find me, then I'm fine.”

One-fifth of participants are not interested in following their samples “[I] don’t really mind what the clever clogs do with it”. The majority of participants (81.2%, N = 81) would like to know more about how their samples are used but are pragmatic in their requests, “It would be interesting to know but if it is more work/expenses for hospitals etc. I don’t mind not knowing” suggesting the “Ability to opt in to receiving updates on research”.

Discussion

This study provides insights from UK CYP on consent procedures and ethical issues surrounding participation in research involving biobanks. It adds valuable data in a field where there is little literature on CYP perspectives.

In our surveyed population we demonstrate CYP have positive attitudes towards participation in research involving biobanks, and acceptability of both prospective and deferred consent is high. Altruism, sample frugality and bodily integrity were important themes for CYP, concurrent with views of adults [23, 24], and CYP participating in critical care trials [21]. We acknowledge that there is hesitancy in a minority of CYP to donate, due to needle phobia, pain, or aversion towards the bodily fluid to be donated. While we expected needle phobia and pain to be main barriers to donation, we were surprised by the young people’s hesitancy to donate stool samples, due to perceived embarrassment.

In line with previous studies involving the views of practitioners [15] and parents [14], CYP were receptive to deferred consent, provided it was obtained appropriately [15]. This is a marked change, compared to a similar small unpublished survey conducted in our centre previously, in which CYP from the same region were less receptive to deferred consent. Post-hoc, we identified two potential factors may have influenced this, although these were not specifically mentioned by the participants.

First, the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The pandemic introduced viral testing on a large scale to the general population, including CYP. During this time, media outlets frequently reported on the scientific progress made into this novel disease, utilizing data generated from COVID-19 swabs taken from the general public. This introduced CYP to a surrogate process of donating biospecimens to biobanks for research and what impact this contribution might have. Having experienced donating biospecimens, attitudes to aforementioned factors might have changed.

Second, in 2020, the new organ donation law in England came into effect, changing the opt-in to an opt-out system [27]. The opt-out system can effectively be seen as a proxy deferred consent, as it assumes every adult is happy to be an organ donor, unless they actively record a decision to be excluded from the donor programme. We postulated that this may have raised awareness of different forms of consent practices nationally. Deferred consent for biobanking assumes consent to take biospecimens with a retrospective option to decline for the sample to be used. The reasoning behind this option is to reduce the number of sample attempts (i.e. blood draws) to minimise pain and distress in children and young people.

The right to assent is protected by the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, article 12, which states: “States Parties shall assure to the child who is capable of forming his or her own views the right to express those views freely in all matters affecting the child, the views of the child being given due weight in accordance with the age and maturity of the child” [28]. Our results clearly show that CYP should be actively involved in the consent procedure, by giving assent in conjunction with their parents, or by being approached for reconsent once they are old enough. Some participants provided accounts of negative personal experiences in hospital and not being involved or listened to, in order to emphasize the importance of CYP participation in their own healthcare and maintaining autonomy. The benefit and need for CYP with capacity to assent has become increasingly clear [29,30,31,32,33]. This is consistent with the attitude that children have grown more independent within the home, school, and medical setting [34], and increasingly seen as autonomous individuals [35]. There are concerns that CYP might lack capacity to give meaningful consent particularly around the complex concept of biobanking [21, 36]. However, there is evidence that even adults lack a deeper understanding of biobanking [23]. McGregor and Ott [37] demonstrated the capacity of adolescents/young adults (aged 12–24 years) to consent is similar to that of adults. Therefore, aiding CYP to provide meaningful informed consent is a pivotal task of the consenting researcher, and should be achievable in most circumstances.

CYP are largely supportive of having medical data stored alongside their biobanked sample and recognized the value of data and risks of data sharing. Due to widespread social media use, CYP are used to providing consent and understanding their risks and benefits of sharing their personal data. CYP with long-term conditions using health technology to manage their illness [38] have highlighted such concerns. Concerns about governance and entrusting their sample to a biobank are legitimate in light of the Alder Hey organ scandal, involving the removal of human tissue and organs of hundreds of deceased children without the knowledge and consent of their parents between 1988 and 1996. Following public inquiry [39], this led to the Human Tissue Act 2004 [40] and new recommendations for consent approaches, to prevent this from happening again [41].

Research requires trust from those willing to participate. It is vital CYP are provided with sufficient, comprehensive information tailored to their age and expected level of understanding. It is important that clear and transparent information on privacy, data and sample handling is available and clearly communicated.

Limitations

Although this study adds to the paucity of community CYP perspectives on consent procedures and ethical issues surrounding biobanking, it has limitations. Most respondents were from the North East of England, and their views might not represent those in the UK as a whole. This study was conducted in a high-income country, and there is currently no evidence to support whether our results might be applicable to low- or middle-income country settings or, other cultural settings. Specific ethical challenges have been reported surrounding the ethical adequacy for large-scale biobanking and sample use during disease outbreaks, for example during the 2014 Ebola outbreak in Africa [42], that are rarely seen in the setting of high-income countries.

Additionally, we acknowledge that most of our participants are older and female CYP, and the perspectives could change if we had a larger proportion of younger CYP. The current number of younger participants was too low to conduct a subset analysis.

The survey allowed for opinions and perspectives to be shared by the participants, but our data lacks the in-depth detail you could get from an interview-based approach.

Conclusions

For CYP in the UK prospective and deferred consent are highly acceptable in the context of biobanking.

CYP should be included in consent procedures for biobank participation, when they reach capacity.

Important themes surrounding consent are altruism, frugality, body integrity and ownership.

Clear communication and justification of the need for biobanking is paramount to ensure willingness to participate in research involving biobanking.

This study highlights the lack of clear guidelines and information around consent procedures for biobanking of samples from children and young persons. We would suggest that national bodies need to develop these in conjunction with active engagement and input from CYP themselves.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analysed for this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CYP:

-

Children and young people

- DIAMONDS:

-

Diagnosis and Management of Febrile Illness using RNA Personalised Molecular Signature Diagnosis

- UK:

-

United Kingdom

- YPAGne:

-

Young Person’s Advisory Group North England

References

Raynor P, Born in Bradford Collaborative G. Born in Bradford, a cohort study of babies born in Bradford, and their parents: protocol for the recruitment phase. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:327.

Jaddoe VW, Mackenbach JP, Moll HA, Steegers EA, Tiemeier H, Verhulst FC, et al. The generation R Study: design and cohort profile. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21(6):475–84.

Zielhuis GA. Biobanking for epidemiology. Public Health. 2012;126(3):214–6.

Hens K, Levesque E, Dierickx K. Children and biobanks: a review of the ethical and legal discussion. Hum Genet. 2011;130(3):403–13.

Hens K, Cassiman JJ, Nys H, Dierickx K. Children, biobanks and the scope of parental consent. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(7):735–9.

Ashcroft JW, Macpherson CC. The complex ethical landscape of biobanking. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4(6):e274–5.

Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences. International Ethical Guidelines for Health-Related Research Involving Humans Geneva, Switzerland: Council for International Organizations of Medical Sciences; 2016. Available from: https://cioms.ch/publications/product/international-ethical-guidelines-for-health-related-research-involving-humans/. Accessed 08 March 2023

Kasperbauer TJ, Halverson C. Adolescent assent and Reconsent for Biobanking: recent developments and emerging ethical issues. Front Med (Lausanne). 2021;8:686264.

Legislation.gov.uk. Mental Capacity Act 2005 2005. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/9/contents. Accessed 08 March 2023.

Commission CQ. Brief guide: capacity and competence to consent in under 18s 2019. Available from: https://www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/Brief_guide_Capacity_and_consent_in_under_18s%20v3.pdf Accessed 08 March 2023.

National Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children. Gillick competency and Fraser guidelines 2022. Available from: https://learning.nspcc.org.uk/child-protection-system/gillick-competence-fraser-guidelines. Accessed 08 March 2023

Legislation.gov.uk. The Medicines for Human Use (Clinical Trials) and Blood Safety and Quality (Amendment) Regulations 2008 941.10 2008. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2008/941/contents/made. Accessed 08 March 2023

Saben JL, Shelton SK, Hopkinson AJ, Sonn BJ, Mills EB, Welham M, et al. The emergency medicine specimen bank: an innovative approach to biobanking in acute care. Acad Emerg Med. 2019;26(6):639–47.

Furyk J, McBain-Rigg K, Watt K, Emeto TI, Franklin RC, Franklin D, et al. Qualitative evaluation of a deferred consent process in paediatric emergency research: a PREDICT study. BMJ Open. 2017;7(11):e018562.

Woolfall K, Frith L, Gamble C, Young B. How experience makes a difference: practitioners’ views on the use of deferred consent in paediatric and neonatal emergency care trials. BMC Med Ethics. 2013;14:45.

Gurwitz D, Fortier I, Lunshof JE, Knoppers BM. Research ethics Children and population biobanks. Science. 2009;325(5942):818–9.

Lipworth W, Forsyth R, Kerridge I. Tissue donation to biobanks: a review of sociological studies. Sociol Health Illn. 2011;33(5):792–811.

Brothers KB. Biobanking in pediatrics: the human nonsubjects approach. Per Med. 2011;8(1):79.

Oliver JM, Slashinski MJ, Wang T, Kelly PA, Hilsenbeck SG, McGuire AL. Balancing the risks and benefits of genomic data sharing: genome research participants’ perspectives. Public Health Genomics. 2012;15(2):106–14.

McGuire AL, Oliver JM, Slashinski MJ, Graves JL, Wang T, Kelly PA, et al. To share or not to share: a randomized trial of consent for data sharing in genome research. Genet Med. 2011;13(11):948–55.

Paquette ED, Derrington SF, Shukla A, Sinha N, Oswald S, Sorce L, et al. Biobanking in the pediatric critical care setting: adolescent/young adult perspectives. J Empir Res Hum Res Ethics. 2018;13(4):391–401.

D’Abramo F, Schildmann J, Vollmann J. Research participants’ perceptions and views on consent for biobank research: a review of empirical data and ethical analysis. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16:60.

Antonova N, Eritsyan K. It is not a big deal: a qualitative study of clinical biobank donation experience and motives. BMC Med Ethics. 2022;23(1):7.

Tozzo P, Fassina A, Caenazzo L. Young people’s awareness on biobanking and DNA profiling: results of a questionnaire administered to Italian university students. Life Sci Soc Policy. 2017;13(1):9.

Khatib F, Jibrin D, Al-Majali J, Elhussieni M, Almasaid S, Ahram M. Views of university students in Jordan towards Biobanking. BMC Med Ethics. 2021;22(1):152.

Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–57.

Legislation.gov.uk. Organ Donation (Deemed Consent) Act 2019 2019. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2019/7/enacted. Accessed 08 March 2023

UN Commission on Human Rights. Convention on the Rights of the Child. Geneva: UN Commission on Human Rights, 1990 7 March 1990. Report No.: E/CN.4/RES/1990/74.

Runeson I, Enskar K, Elander G, Hermeren G. Professionals’ perceptions of children’s participation in decision making in healthcare. J Clin Nurs. 2001;10(1):70–8.

Larsson I, Staland-Nyman C, Svedberg P, Nygren JM, Carlsson IM. Children and young people’s participation in developing interventions in health and well-being: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):507.

Young B, Moffett JK, Jackson D, McNulty A. Decision-making in community-based paediatric physiotherapy: a qualitative study of children, parents and practitioners. Health Soc Care Community. 2006;14(2):116–24.

Knopf AS, Ott MA, Liu N, Kapogiannis BG, Zimet GD, Fortenberry JD, et al. Minors’ and young adults’ experiences of the research consent process in a phase II safety study of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(6):747–54.

Marsh V, Mwangome N, Jao I, Wright K, Molyneux S, Davies A. Who should decide about children’s and adolescents’ participation in health research? The views of children and adults in rural Kenya. BMC Med Ethics. 2019;20(1):41.

Vaknin O, Zisk-Rony RY. Including children in medical decisions and treatments: perceptions and practices of healthcare providers. Child Care Health Dev. 2011;37(4):533–9.

Martenson EK, Fagerskiold AM. A review of children’s decision-making competence in health care. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17(23):3131–41.

Susman EJ, Dorn LD, Fletcher JC. Participation in biomedical research: the consent process as viewed by children, adolescents, young adults, and physicians. J Pediatr. 1992;121(4):547–52.

McGregor KA, Ott MA. Banking the future: adolescent capacity to consent to biobank research. Ethics Hum Res. 2019;41(4):15–22.

Blower S, Swallow V, Maturana C, Stones S, Phillips R, Dimitri P, et al. Children and young people’s concerns and needs relating to their use of health technology to self-manage long-term conditions: a scoping review. Arch Dis Child. 2020;105(11):1093–104.

The Royal Liverpool Children's Inquiry. Report London: The Stationery Office; 2001. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/250934/0012_ii.pdf.

Legislation.gov.uk. Human Tissue Act 2004 2004. Available from: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2004/30/contents. Accessed 08 March 2023

Bauchner H, Vinci R. What have we learnt from the Alder Hey affair? That monitoring physicians’ performance is necessary to ensure good practice. BMJ. 2001;322(7282):309–10.

Saxena A, Gomes M. Ethical challenges to responding to the Ebola epidemic: the World Health Organization experience. Clin Trials. 2016;13(1):96–100.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Young Person’s Advisory Group North England and their connections to local secondary schools for making this project possible.

DIAMONDS consortium

Michael Levin7, Aubrey Cunnington7, Jethro Herberg7, Myrsini Kaforou7, Victoria Wright7, Evangelos Bellos7, Claire Broderick7, Samuel Channon-Wells7 ,Samantha Cooray7, Tisham De7, Giselle D’Souza7, Leire Estramiana Elorrieta7, Diego Estrada-Rivadeneyra7, Rachel Galassini7, Dominic Habgood-Coote7, Shea Hamilton7, Heather Jackson7, James Kavanagh7, Mahdi Moradi Marjaneh7, Samuel Nichols7, Ruud Nijman7, Harsita Patel7, Ivana Pennisi7, Oliver Powell7, Ruth Reid7, Priyen Shah7, Ortensia Vito7, Elizabeth Whittaker7, Clare Wilson7, Rebecca Womersley7, Amina Abdulla8, Sarah Darnell8, Sobia Mustafa8, Pantelis Georgiou9, Jesus-Rodriguez Manzano10, Nicolas Moser9, Michael Carter11, Shane Tibby11, Jonathan Cohen11, Francesca Davis11, Julia Kenny11, Paul Wellman11, Marie White11, Matthew Fish12, Aislinn Jennings13, Manu Shankar-Hari13, Katy Fidler14, Dan Agranoff15, Julia Dudley14, Vivien Richmond14, Matthew Seal15, Saul Faust16, Dan Owen16, Ruth Ensom16, Sarah McKay16, Diana Mondo17, Mariya Shaji17, Rachel Schranz17, Prita Rughnani18, Amutha Anpananthar19, Susan Liebeschuetz20, Anna Riddell18, Divya Divakaran19, Louise Han19, Nosheen Khalid18, Ivone Lancoma Malcolm19, Jessica Schofield19, Teresa Simagan19, Mark Peters21, Alasdair Bamford21, Lauran O’Neill21, Nazima Pathan22, Esther Daubney23, Debora White23, Melissa Heightman24, Sarah Eisen24, Terry Segal24, Lucy Wellings24, Simon B Drysdale25, Nicole Branch25, Lisa Hamzah25, Heather Jarman25, Maggie Nyirenda25, Lisa Capozzi26, Emma Gardiner26, Robert Moots27, Magda Nasher28, Anita Hanson28, Michelle Linforth27, Sean O’Riordan29, Donna Ellis29, Akash Deep30, Ivan Caro30, Fiona Shackley31, Arianna Bellini31, Stuart Gormley31, Samira Neshat32, Barnaby J Scholefield33, Ceri Robbins33, Helen Winmill33, Stéphane C Paulus34, Andrew J Pollard35, Mark Anthony36, Sarah Hopton36, Danielle Miller36, Zoe Oliver36, Sally Beer36, Bryony Ward36, Shrijana Shrestha37, Meeru Gurung37, Puja Amatya37, Bhishma Pokhrel37, Sanjeev Man Bijukchhe37, Madhav Chandra Gautam37, Peter O’Reilly35, Sonu Shrestha35, Federico Martinón-Torres38, Antonio Salas38, Fernando Álvez González38, Sonia Ares Gómez38, Xabier Bello38, Mirian Ben García38, Fernando Caamaño Viña38, Sandra Carnota38, María José Curras-Tuala38, Ana Dacosta Urbieta38, Carlos Durán Suárez38, Isabel Ferreiros Vidal38, Luisa García Vicente38, Alberto Gómez-Carballa38, Jose Gómez Rial38, Pilar Leboráns Iglesias38, Narmeen Mallah38, Nazareth Martinón-Torres38, José María Martinón Sánchez38, Belén Mosquera Perez38, Jacobo Pardo-Seco38, Sara Pischedda38, Sara Rey Vázquez38, Irene Rivero Calle38, Carmen Rodríguez-Tenreiro38, Lorenzo Redondo-Collazo38, Sonia Serén Fernández38, Marisol Vilas Iglesias38, Enital D Carrol39, Elizabeth Cocklin39, Abbey Bracken39, Ceri Evans40 Aakash Khanijau39, Rebecca Lenihan39, Nadia Lewis-Burke39, Karen Newall41, Sam Romaine39, Jennifer Whitbread39, Maria Tsolia42, Irini Eleftheriou42, Nikos Spyridis42, Maria Tambouratzi42, Despoina Maritsi42, Antonios Marmarinos42, Marietta Xagorari42, Lourida Panagiota43, Pefanis Aggelos43, Akinosoglou Karolina44, Gogos Charalambos44, Maragos Markos44, Voulgarelis Michalis45, Stergiou Ioanna45, Marieke Emonts1,2, Emma Lim1,5,6, John Isaacs2, Kathryn Bell46, Stephen Crulley46, Daniel Fabian46, Evelyn Thomson46, Diane Walia46, Caroline Miller46, Ashley Bell46, Fabian JS van der Velden1,2, Geoff Shenton47, Ashley Price48, Owen Treloar2, Daisy Thomas1, Pablo Rojo49, Cristina Epalza49, Serena Villaverde49, Sonia Márquez49, Manuel Gijón49, Fátima Marchín49, Laura Cabello49, Irene Hernández49, Lourdes Gutiérrez49, Ángela Manzanares49, Taco W Kuijpers50, Martijn van de Kuip50, Marceline van Furth50, Merlijn van den Berg50, Giske Biesbroek50, Floris Verkuil50, Carlijn W van der Zee50, Dasja Pajkrt50, Michael Boele van Hensbroek50, Dieneke Schonenberg50, Mariken Gruppen50, Sietse Nagelkerke50, Machiel H Jansen50, Ines Goedschalckx51, Lorenza Romani52, Maia De Luca52, Sara Chiurchiù52, Constanza Tripiciano52, Stefania Mercadante52, Clementien L Vermont53, Henriëtte A Moll54, Dorine M Borensztajn54, Nienke N Hagedoorn54, Chantal Tan54, Joany Zachariasse54, Willem A Dik55, Shen Ching-Fen56, Dace Zavadska57, Sniedze Laivacuma58, Aleksandra Rudzate57, Diana Stoldere57, Arta Barzdina57, Elza Barzdina57, Monta Madelane59, Dagne Gravele59, Dace Svile59, Romain Basmaci60, Noémie Lachaume60, Pauline Bories60, Raja Ben Tkhayat60, Laura Chériaux60, Juraté Davoust60, Kim-Thanh Ong60, Marie Cotillon60, Thibault de Groc60, Sébastien Le60, Nathalie Vergnault60, Hélène Sée60, Laure Cohen60, Alice de Tugny60, Nevena Danekova60, Marine Mommert-Tripon61, Marko Pokorn62, Mojca Kolnik62, Tadej Avčin62, Tanja Avramoska62, Natalija Bahovec63, Petra Bogovič63, Lidija Kitanovski62, Mirijam Nahtigal63, Lea Papst63, Tina Plankar Srovin63, Franc Strle63, Katarina Vincek63, Michiel van der Flier64, Wim JE Tissing65, Roelie M Wösten-van Asperen66, Sebastiaan J Vastert67, Daniel C Vijlbrief68, Louis J Bont69, Tom FW Wolfs69, Coco R Beudeker69, Sanne C Hulsmann69, Philipp KA Agyeman70, Luregn Schlapbach71, Christoph Aebi70, Mariama Usman70, Stefanie Schlüchter70, Verena Wyss70, Nina Schöbi70, Elisa Zimmermann70, Marion Meier71, Kathrin Weber71, Eric Giannoni72, Martin Stocker73, Klara M Posfay-Barbe74, Ulrich Heininger75, Sara Bernhard-Stirnemann76, Anita Niederer-Loher77, Christian Kahlert78, Giancarlo Natalucci79, Christa Relly80, Thomas Riedel81, Christoph Berger81, Colin Fink82, Marie Voice82, Leo Calvo-Bado82, Michael Steele82, Jennifer Holden82, Andrew Taylor82, Ronan Calvez82, Catherine Davies82, Benjamin Evans82, Jake Stevens82, Peter Matthews82, Kyle Billing82, Werner Zenz83, Alexander Binder83, Benno Kohlmaier83, Daniel S Kohlfürst83, Nina A Schweintzger83, Christoph Zurl83, Susanne Hösele83, Manuel Leitner83, Lena Pölz83, Alexandra Rusu83, Glorija Rajic83, Bianca Stoiser83, Martina Strempfl83, Manfred G Sagmeister83, Sebastian Bauchinger83, Martin Benesch84, Astrid Ceolotto83, Ernst Eber83, Siegfried Gallistl83, Harald Haidl83, Almuthe Hauer83, Christa Hude83, Andreas Kapper85, Markus Keldorfer86, Sabine Löffler86, Tobias Niedrist87, Heidemarie Pilch86, Andreas Pfleger88, Klaus Pfurtscheller89, Siegfried Rödl89 , Andrea Skrabl-Baumgartner83, Volker Strenger84, Elmar Wallner85, Maike K Tauchert90, Ulrich von Both91, Laura Kolberg91, Patricia Schmied91, Ioanna Mavridi91, Irene Alba-Alejandre92, Katharina Danhauser93, Niklaus Haas94, Florian Hoffmann95, Matthias Griese96, Tobias Feuchtinger97, Sabrina Juranek98, Matthias Kappler96, Eberhard Lurz99, Esther Maier98, Karl Reiter95, Carola Schoen95, Sebastian Schroepf100, Shunmay Yeung101, Manuel Dewez101, David Bath102, Elizabeth Fitchett101, Fiona Cresswell101, Effua Usuf103, Kalifa Bojang103, Anna Roca103, Isatou Sarr103, Momodou Ndure103

8Children’s Clinical Research Unit, St Mary’s Hospital, Praed Street, London W2 1NY, UK

9Imperial College London, Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering, South Kensington Campus, London, SW7 2AZ, UK

10Imperial College London, Department of Infectious Disease, Section of Adult Infectious Disease, Hammersmith Campus, London, W12 0NN, UK

11Evelina London Children’s Hospital, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

12Department of Infectious Diseases, School of Immunology and Microbial Sciences, King’s College London, London, UK

13Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

14Royal Alexandra Children's Hospital, University Hospitals Sussex, Brighton, UK

15Dept of Infectious Diseases, University Hospitals Sussex, Brighton, UK

16NIHR Southampton Clinical Research Facility, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust and University of Southampton, UK

17Department of R&D, University Hospital Southampton NHS Foundation Trust, UK

18Royal London Hospital, Whitechapel Rd, London E1 1FR, UK

19Whipps Cross University Hospital, Whipps Cross Road, London, E11 1NR, UK

20Newham University Hospital, Glen Rd, London E13 8SL, UK

21Great Ormond Street Hospital, London, WC1N 3JH, UK

22Department of Paediatrics, University of Cambridge, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK

23Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 0QQ, UK

24University College London Hospital, Euston Road, London NW1 2BU, UK

25St George’s Hospital, Blackshaw Road, London SW17 0QT, UK

26University Hospital Lewisham, London SE13 6LH, UK

27Aintree University Hospital, Lower Lane, Liverpool L9 7AL, UK

28Royal Liverpool Hospital, Prescot St, Liverpool L7 8XP, UK

29Leeds Children’s Hospital, Leeds LS1 3EX, UK

30Kings College Hospital, Denmark Hill, London SE5 9RS, UK

31Sheffield Children’s Hospital, Broomhall, Sheffield S10 2TH, UK

32Leicester General Hospital, Leicester LE1 5WW, UK

33Birmingham Children’s Hospital, Steelhouse Lane, Birmingham B4 6NH, UK

34Department of Paediatrics, University of Oxford, UK

35Oxford Vaccine Group, University of Oxford, UK

36John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford, UK

37Paediatric Research Unit, Patan Academy of Health Sciences, Kathmandu, Nepal

38Translational Pediatrics and Infectious Diseases, Pediatrics Department, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Santiago, Santiago de Compostela, Spain

39Institute of Infection, Veterinary and Ecoological Sciences, University of Liverpool, Liverpool, UK

40Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, Department of Infectious Diseases, Eaton Road, Liverpool, L12 2AP, UK

41Alder Hey Children’s Hospital, Clinical Research Business Unit, Eaton Road, Liverpool, L12 2AP, UK

422nd Department of Pediatrics, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA), Children’s Hospital “P, and A. Kyriakou”, Athens, Greece

431st Department of Infectious Diseases, General Hospital “Sotiria”, Athens, Greece

44Pathology Department, University of Patras, General Hospital “Panagia i Voithia”, Greece

45Pathophysiology Department, Medical Faculty, National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (NKUA), General Hospital “Laiko”, Athens, Greece

46Great North Children’s Hospital, Paediatric Research Team, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

47Great North Children’s Hospital, Paediatric Oncology, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

48Department of Infection & Tropical Medicine, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Newcastle upon Tyne, United Kingdom

49Servicio Madrileño de Salud, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, Spain

50Amsterdam UMC, Emma Children's Hospital, Dept of Pediatric Immunology, Rheumatology and Infectious Disease, University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

51Sanquin, Dept of Molecular Hematology, University Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

52Infectious Disease Unit, Academic Department of Pediatrics, Bambino Gesù Children's Hospital, IRCCS, Rome 00165, Italy

53Erasmus MC-Sophia Children’s Hospital, Department of Paediatric Infectious Diseases & Immunology, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

54Erasmus MC-Sophia Children’s Hospital, Department of General Paediatrics, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

55Erasmus MC, Department of Immunology, Rotterdam, the Netherlands

56Department of Pediatrics, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, College of Medicine, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan, Taiwan

57Children’s Clinical University Hospital, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia

58Riga East Clinical Hospital, Riga Stradins University, Riga, Latvia

59Children’s Clinical University Hospital, Riga, Latvia

60Service de Pédiatrie-Urgences, AP-HP, Hôpital Louis-Mourier, F-92700 Colombes, France

61bioMérieux—Open Innovation & Partnerships Department, Lyon, France

62University Children's Hospital, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Slovenia

63Department of Infectious diseases, University Medical Centre Ljubljana, Slovenia

64Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Wilhelmina Children’s Hospital, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands

65Princess Maxima Center for Pediatric Oncology, Utrecht, the Netherlands

66Pediatric Intensive Care Unit, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands

67Pediatric Rheumatology, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands

68Pediatric Neonatal Intensive Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands

69Pediatric Infectious Disease and Immunology, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, the Netherlands

70Department of Pediatrics, Inselspital, Bern University Hospital, University of Bern, Switzerland

71Department of Intensive Care and Neonatology, and Children`s Research Center, University Children`s Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

72Clinic of Neonatology, Department Mother-Woman-Child, Lausanne University Hospital and University of Lausanne, Switzerland

73Department of Pediatrics, Children’s Hospital Lucerne, Lucerne, Switzerland

74Pediatric Infectious Diseases Unit, Children’s Hospital of Geneva, University Hospitals of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland

75Infectious Diseases and Vaccinology, University of Basel Children’s Hospital, Basel, Switzerland

76Children’s Hospital Aarau, Aarau, Switzerland

77Division of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology, Children’s Hospital of Eastern Switzerland St. Gallen, St. Gallen, Switzerland

78Department of Neonatology, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

79Division of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology, and Children’s Research Center, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

80Children’s Hospital Chur, Chur, Switzerland

81Division of Infectious Diseases and Hospital Epidemiology, and Children’s Research Center, University Children’s Hospital Zurich, Switzerland

82Micropathology Ltd, The Venture Center, University of Warwick Science Park, Sir William Lyons Road, Coventry, CV4 7EZ, UK

83Department of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Division of General Pediatrics, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria

84Department of Pediatric Hematooncology, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria

85Department of Internal Medicine, State Hospital Graz II, Location West, Graz, Austria

86University Clinic of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine Graz, Medical University Graz, Graz, Austria

87Clinical Institute of Medical and Chemical Laboratory Diagnostics, Medical University Graz, Graz, Austria

88Department of Pediatric Pulmonology, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria

89Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria

90Biobanking and BioMolecular Resources Research Infrastructure—European Research Infrastructure Consortium (BBMRI-ERIC), Neue Stiftingtalstrasse 2/B/6, 8010, Graz, Austria

91Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Department of Pediatrics, Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

92Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

93Division of Pediatric Rheumatology, Department of Pediatrics, Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

94Department of Pediatric Cardiology and Pediatric Intensive Care, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Germany

95Paediatric Intensive Care Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

96Division of Pediatric Pulmonology, Department of Pediatrics, Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

97Division of Pediatric Haematology & Oncology, Department of Pediatrics, Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

98Division of General Pediatrics, Department of Pediatrics, Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

99Division of Pediatric Gastroenterology, Department of Pediatrics, Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

100Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Department of Pediatrics, Dr. von Hauner Children’s Hospital, University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

101Clinical Research Department, Faculty of Infectious and Tropical Disease, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

102Department of Global Health and Development, Faculty of Public Health and Policy, London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, UK

103Medical Research Council at LSHTM, Fajara, the Gambia

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under grant agreement No. 848196. The funding body played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data, and in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

EL, JBa, and ME conceptualized the project. LG, JBr, JBa, ER and EL designed the survey and collected the data. FvdV, LG, JBr, LH, JC, and EL analysed the data. JH and RG are responsible for the ethics within the DIAMONDS study. FvdV, EL and LG wrote the manuscript. All authors read, revised, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study is part of the DIAMONDS study and has ethics approval for the UK under: IRAS 209035, REC 16/LO/1684.

This study was registered and had its protocols approved by the Newcastle upon Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust under local audit registry number 13906.

This study and its methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and local NHS Trust policies.

Participants were members of the community, and not clinical patients. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Written informed consent for the survey from parents or legal guardians was not required or obtained for patients under 16 years of age, with approval from the Newcastle and North Tyneside Research Ethics Committee. Parental input was seen as a barrier to CYP participation and would potentially influence the responses. The co-produced element of the project ensured the subject and information created was CYP friendly, which significantly impacts their capacity to understand the circumstances and details of the research being proposed. The information was written and presented in a CYP friendly manner, to ensure CYP had all the information required to consent. Gillick competence was applied: reading the introductory information paragraph preceding the survey and the ability to complete the survey constituted consent for participants under the age of 16 years.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

van der Velden, F.J.S., Lim, E., Gills, L. et al. Biobanking and consenting to research: a qualitative thematic analysis of young people’s perspectives in the North East of England. BMC Med Ethics 24, 47 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-023-00925-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-023-00925-w