Abstract

Background

We aimed to evaluate the effect of cranberry supplementation on serum liver enzymes, hepatic steatosis, and cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with non-alcoholic fatty liver (NAFLD).

Methods

In the present parallel-designed randomized controlled clinical trial, 110 patients with NAFLD were enrolled. The patients were randomized to receive 144 mg cranberry capsule or placebo for 6 months. The primary efficacy of the treatment was lipid profile, glycemic measurements, and liver enzyme levels.

Results

The data were reported for 46 in the supplementation group and 48 in the placebo group. The patient’s mean (SD) age was 43.16 (11.08) years. No significant differences between groups were observed regarding the post-intervention level of liver enzyme. The mean after-intervention levels of total cholesterol (p < 0.001) and triglyceride (p = 0.01) were significantly lower in the intervention group compared with the placebo group. At the end of the study, the mean insulin and HOMA-IR levels were significantly lower in the cranberry group compared with the placebo group. Significantly more patients in the cranberry group experienced a decrease in steatosis level compared with the control group.

Conclusion

The results of the present study showed that cranberry supplementation had a positive effect on some lipid profiles, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in patients with NAFLD.

Trial registration

IRCT20200725048200N1; first registration date: 11.8.2020.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is defined by excessive accumulation of lipids in the liver, which is not induced by alcohol intake, drug use, or viral hepatitis [1]. The NAFLD prevalence was reported as 25.24% worldwide, with a high prevalence in the Middle East countries [2]. NAFLD is related to other diseases such as kidney and cardiovascular diseases representing the effects of this disease on the body [3].

Considering the burden of NAFLD, researchers have mainly focused on examining new and effective methods for the prevention and treatment of this disease [4]. Different disease management options such as lifestyle interventions, drug and vitamin supplements therapy, phlebotomy, and surgical interventions were suggested to accomplish on NAFLD patients [5]. However, the majority of these procedures are ineffective and some methods like various types of surgeries are invasive and can be associated with other complications. Therefore, better methods and medication had to be investigated for NAFLD treatment.

Nowadays, an increasing number of studies have focused on the efficacy of herbal medicine in NAFLD patients [6]. Some studies showed the positive effect of herbal medication along with lifestyle modification in patients with NAFLD [6]. Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) is a fruit with high content of different polyphenols [7]. Different animal studies showed the promising effect of cranberry on liver enzymes and hepatic steatosis [8, 9]. Moreover, various human studies have also focused on the effect of Cranberry capsules (240–1500 mg/day) [9,10,11,12] and Cranberry juice (240–750 ml/days) [13,14,15,16,17,18,19] on cardiometabolic risk factors and providing mixed results. Some studies reported the protective effect of cranberry on TC [11], LDL-C [11], HDL-C [19], FPG [16], and blood pressure [15]. However, the results of a recent systematic review and meta-analysis study concluded that cranberry supplementation has significantly positive effects on blood pressure and weight loss in patients with diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. However, no favorable effect was observed on glycemic measurements and lipid profile [20]. To the best of our knowledge, so far, only one study has assessed the effect of cranberry in patients with NAFLD [21]. Hormoznejad et al. have assessed the effect of 288 mg of cranberry supplementation for 3 months on cardiometabolic risk factors and steatosis grade in patients with NAFLD and showed a significantly greater reduction of alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and insulin in the cranberry group than in the placebo group. The intervention duration in this study was limited and they recommended long-term clinical trials in NAFLD patients [21].

Considering the high antioxidant capacity of cranberry and owing to the involvement of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of NAFLD, we postulated that a hypocaloric diet along with cranberry supplementation maybe effective in the management of NAFLD. Due to the lack of studies in this regard, in the present clinical trial, we evaluated the effect of cranberry supplementation on serum liver enzymes, hepatic steatosis, and glycemic and lipid profiles in patients with NAFLD.

Methods

Patients

In the present parallel-designed triple-blind randomized controlled clinical trial, the previously diagnosed patients with NAFLD who were referred to the liver disease clinic of Imam Reza educational hospital, Tabriz, Iran from august 2020 were enrolled. The patients were diagnosed based on liver ultrasonography previously by expert gastroenterologists. Adult patients aged more than 18 years were included. The pregnant and breastfeeding patients, the patients with diabetes, other liver diseases, heart, renal and pulmonary failure, patients with alcohol intake, and the ones who used antioxidant and vitamin supplements other than vitamin E were ineligible.

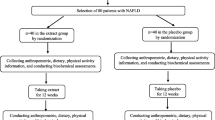

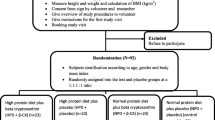

One hundred and ten patients with NAFLD participated in the present trial. Simple randomization was done using a computer-generated randomization chart by the GraphPad QuickCalcs tool. A sequentially numbered sealed envelope was used to randomize participants into two groups. A researcher who did not play any role in the other part of the investigation developed the randomization chart and assigned the patients into the intervention groups. All participants who have received a hypocaloric diet of 500 kcal less per day than estimated energy requirements and vitamin E supplement. The patients in the intervention group (n = 55) received a single capsule of cranberry (144 mg) and the patients in the placebo group (n = 55) received the placebo for 6 months. The patients were advised to take the capsules after lunch. To increase the patients’ compliance to intervention, participants were fully informed regarding the trial before the initiation of interventions. Moreover, the pre-planned telephone call was undertaken to answer questions and address any issues that arise.

Cranberry, and placebo were purchased from Shari Company, Iran. The cranberry capsule includes 144 mg Vaccinium macrocarpon (equal to 13 g dried cranberry fruit). The placebo includes the same base formula without the active ingredient. Cranberry and placebo were the same, labeled as A and B, and ordered by a researcher who was not involved in other parts of the clinical trial. The patients, the outcome assessor, and the statistician were blind to group assignment.

All participants have signed full written consent. The ethics committee of Tabriz University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol (Ethics code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.090). The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Tabriz University of medical sciences. The trial was registered at the Iranian registry of clinical trials (Identifier NO. IRCT20200725048200N1; first registration date: 11.8.2020).

The sample size was calculated using G-power software based on the result of a previous study [15] about the effect of cranberry juice on the glycemic indices and by the presumption of a two-sided significance level of 5% and power of 80% with equal allocation to the two arms that necessitate a sample size of 37 in each group. To allow for dropouts, 55 patients were recruited.

Measurements

The participants were visited every month during the intervention. In all visits, compliance with the intervention and lifestyle modifications were checked. If participants consume > 80% of their prescribed medication were considered compliant.

Evaluation of the therapeutic efficacy

The primary endpoints were lipid profile [total cholesterol (TC), triglyceride (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C)], glycemic measurements [fasting blood sugar (FBS), and insulin level], liver enzymes [alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alkaline phosphatase (ALP)] levels.

Anthropometric characteristics, including weight, and height were measured at the beginning and end of the study. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a tape measure. Weight was measured using a Seca weighing scale to the nearest 0.1 kg. BMI was also calculated as weight in kilograms (kg)/height in meters squared (m2).

After 10-h fasting, a blood sample was obtained. All measurements were done in the same laboratory and using the same procedures. The colorimetric method (Parsazmoun, Tehran, Iran) was used for measuring liver enzymes, FBS, TG, TC, and HDL-C levels. ELISA method (Monobind, USA) was used for measuring serum insulin level. The concentration of LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald formula and the homeostatic model assessment insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR) was calculated according to Gayoso-Diz et al. formula: HOMA-IR = fasting glucose (mmol/l)* fasting insulin (lU/mL)/ 22.5.

Statistical analysis

SPSS version 16 was used for statistical analysis. Kolmogorov-smirnov test was used for assessing data distribution. Mean and standard deviations (SD) were used for reporting the continuous variables and frequency and percentage were used for reporting categorical data. A paired sample t-test was used for comparison of the before- and after-intervention values in each group. For between-group comparisons, the chi-square test and independent t-test were used where appropriate. For comparison of the post-intervention values adjusted for age, sex, BMI, and baseline values, a one-way analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

From a total of 110 patients with NAFLD, nine patients in the intervention group and seven patients in the control group were lost to follow-up. The data were stated for 94 patients (46 in the cranberry group and 48 in the placebo group) (Fig. 1).

The mean (SD) age of the participants was 43.16 (11.08) years, 47.9% of them were male, and 76.6% of them were overweight or obese. The baseline demographic and clinical characteristics were not significantly different between the two groups (Table 1).

As shown in Table 2, the mean liver enzyme levels were significantly decreased in the placebo group (p < 0.001), however, in the intervention group, there was a significant reduction in only the ALP levels. The results of the ANCOVA test showed that there were no significant differences between groups regarding the after-intervention level of liver enzymes after adjusting for age, sex, BMI, and baseline values.

In the term of lipid profile measurements, the mean after-intervention levels of total cholesterol (p < 0.001) and triglyceride (p = 0.01) were significantly lower in the intervention group compared with the placebo group after adjusting for baseline values, age, sex, BMI and baseline values (Table 2).

The mean level of glycemic indices was significantly decreased in both groups. However, the results of the ANCOVA test indicated that that at the end of the intervention, the mean insulin, and HOMA-IR levels were significantly lower in the cranberry group compared with the placebo group.

The changes in hepatic steatosis grade are shown in Fig. 2. Significantly more patients in the cranberry group experienced a decrease in steatosis level compared with the control group (P < 0.01). Moreover, 8.7% of patients in the cranberry group experienced a one-point increase in steatosis level and the steatosis level did not increase in any patients in the control group, however, the differences were not statistically significant between groups (p = 0.06).

Discussion

This RCT assessed the effect of cranberry supplementation on cardiometabolic risk factors and liver function tests in patients with NAFLD. The results showed that in the term of cardiometabolic risk factors, the mean reduction in total cholesterol, triglyceride, insulin, and HOMA-IR levels in the cranberry group was significantly higher compared with the placebo group. The effect of cranberry supplementation of glycemic measurements was in agreement with the result of a previous study in patients with NAFLD [21]. Hormoznejad et al. in patients with NAFLD showed that cranberry supplementation had a significant positive effect on insulin and HOMA-IR levels in patients with NAFLD [21]. In studies with patients with type 2 diabetes, the positive effect of cranberry supplementation on insulin levels, and HOMA-IR have been shown [22]. The favorable effect of cranberry on insulin sensitivity reported in this study cannot be related to variations in energy and, bodyweight since no changes were observed in these variables between the two groups. The positive effect of cranberry on glycemic measurement may be because of the improved insulin sensitivity [23].

The result of this study indicated that the mean serum FBS was significantly decreased in both groups. Although the mean decrease in serum FBS was higher in the cranberry group compared with the placebo group, the differences were not statistically significant. This finding is in line with the result of a previous study [21]. Some previous studies reported a significant decrease in serum glucose level by cranberry consumption [16, 24, 25]. The observed decrease in FBS in the cranberry group may partly because of the effect of cranberry on a delay in the gastric uptake of glucose or distribution of glucose to insulin-sensitive tissues [24]. Moreover, studies indicated that vitamin E and calorie restriction had a favorable effect on serum glucose levels [26, 27]. So, the significant decrease in serum FBS in the placebo group may be explained by the consumption of vitamin E and restriction of daily calories.

In the present study, we also observed significant differences in changes in TC and TG levels in the cranberry group compared with the placebo group. This finding is opposed to the result of a previous study in NAFLD patients [21]. This discrepancy may be partly related to differences in the intervention types between the two studies. The patients in the present study received vitamin E and energy restriction as routine treatments, however, in Hormoznejad et al. study the patients only received energy restriction as a routine treatment. A previous study on animal models showed the synergistic antioxidant effect of vitamin E and anthocyanins. Antioxidants in fruits had a lipid-lowering effect in a previous clinical trial [28]. Moreover, the duration, and supplement dosage were different in the two studies. In patients with type two diabetes, Lee et al. also showed a positive effect of cranberry supplementation on total cholesterol levels but not triglyceride levels [11]. A systematic review and meta-analysis study that reviewed the effect of cranberry supplementation on cardiometabolic risk factors also did not observe the significant effect of cranberry on lipid profile [20]. Our findings were inconsistent with the results of this meta-analysis that may be partly owing to the differences in including populations. We included the patients with NAFLD, however, none of the included studies in the meta-analysis involved the NAFLD patients and mostly studies the patients with type 2 diabetes or metabolic syndrome.

The observed positive effect of cranberry supplementation on lipid profile in the present study may be somewhat due to the polyphenol content of cranberry. Studies have indicated high content of tannins in cranberry increases the uptake of cholesterol in the liver [29]. Moreover, tannins may increase the excretion of cholesterol by binding to the bile acids in the intestine [30, 31].

We did not observe significant differences between the cranberry and placebo groups in terms of changes in liver enzyme levels. The only human study that assessed the effect of cranberry supplementation in patients with NAFLD reported significant differences between cranberry and placebo groups regarding changes in ALT level but not AST and ALP levels [21]. Faheem et al. also showed the effect of cranberry on decreasing liver enzymes level in rat models [8]. Other studies in fat models also indicated the promising effect of anthocyanins on liver enzyme levels [9]. A plausible explanation for the observed discrepancy between the results might be related to the differences in cranberry doses used in these studies. In the present study, we used the dose of 144 mg/day, however, Hormoznejad et al. used higher doses of cranberry (288 mg/day).

We observed significant differences between the two groups regarding changes in hepatic steatosis status. In an animal study, Anhe et al. also reported significant changes in steatosis status following cranberry supplementation [23]. Hormoznejad et al. also reported a significant reduction in hepatic steatosis in both cranberry and placebo groups [21]. The probable explanation for the positive effect of cranberry on hepatic steatosis may be related to the activation of PPAR-α by Pterostilbene, a stilbenoid found in cranberry. The activation of PPAR- α modulates pathways controlling the increased fatty acid β-oxidation and decreased triglyceride content in the liver and lowers plasma lipid levels in animal models [32]. Moreover, studies indicated that anthocyanins found in cranberry had a positive effect on liver steatosis in animal models [8, 9, 33, 34]. In the present study, the grade of steatosis was increased in four patients in the cranberry group. We postulated that other factors that were not controlled in the present study such as genetic variations, consumption of fructose, monounsaturated fatty acids, and trans-fatty acids may aggravate NAFLD, or alcohol use may responsible for this observation [35]. Although none of the patients in the present study reported the consumption of alcohol, however as alcohol consumption is illegal in Iran, most patients did not report the real amount of alcohol consumption.

The results of the present study should be interpreted considering the potential limitations of the study. We did not measure serum inflammatory and oxidative indices. Moreover, we assessed the steatosis status using the ultra-sonographic examination. Although histological assessment is the best way of assessing hepatic steatosis since liver biopsy is an invasive procedure we used ultrasound technique as an appropriate method for monitoring NAFLD [36].

Moreover, we did not control all confounders such as genetic polymorphism and nutrient intake that may affect the findings.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the results of the present study showed that cranberry supplementation had a positive effect on some lipid profiles, insulin resistance, and hepatic steatosis in patients with NAFLD. However, considering the limitations of the study, more long-term studies with larger sample size and more valid methods of assessing hepatic steatosis are needed to confirm these preliminary results.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to due institution’s policy but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HOMA-IR:

-

Homeostatic model assessment insulin resistance index

- ALP:

-

Alkaline phosphatase

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- FBS:

-

Fasting blood sugar

- LDL-C:

-

Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- HDL-C:

-

High-density lipoprotein cholesterol

- TG:

-

Triglyceride

- TC:

-

Total cholesterol

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

References

McCullough AJ. The clinical features, diagnosis and natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8(3):521–33.

Younossi ZM, Koenig AB, Abdelatif D, Fazel Y, Henry L, Wymer M. Global epidemiology of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease—meta-analytic assessment of prevalence, incidence, and outcomes. Hepatology. 2016;64(1):73–84.

Younossi Z, Anstee QM, Marietti M, Hardy T, Henry L, Eslam M, et al. Global burden of NAFLD and NASH: trends, predictions, risk factors and prevention. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;15(1):11–20.

Mitra S, De A, Chowdhury A. Epidemiology of non-alcoholic and alcoholic fatty liver diseases. Transl Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;5:16:1–17.

Beaton MD. Current treatment options for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis. Can J Gastroenterol. 2012;26(6):353–7.

Xu Y, Guo W, Zhang C, Chen F, Tan HY, Li S, et al. Herbal medicine in the treatment of non-alcoholic fatty liver diseases-efficacy, action mechanism, and clinical application. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1–19.

Narwojsz A, Tańska M, Mazur B, Borowska EJ. Fruit physical features, phenolic compounds profile and inhibition activities of cranberry cultivars (Vaccinium macrocarpon) compared to wild-grown cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccus). Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2019;74(3):300–6.

Faheem SA, Saeed NM, El-Naga RN, Ayoub IM, Azab SS. Hepatoprotective effect of cranberry Nutraceutical extract in non-alcoholic fatty liver model in rats: impact on insulin resistance and Nrf-2 expression. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:1–16.

Valenti L, Riso P, Mazzocchi A, Porrini M, Fargion S, Agostoni C. Dietary anthocyanins as nutritional therapy for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2013;2013:1–8.

Eftekhari M, Alaei M, Khosropanah S, Rajaeifard A, Akbarzadeh M. Effects of cranberry supplement on metabolic syndrome. 2014;22:963–73.

Lee IT, Chan YC, Lin CW, Lee WJ, Sheu WH. Effect of cranberry extracts on lipid profiles in subjects with type 2 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2008;25(12):1473–7.

Chambers BK. Can cranberry supplementation reduce risks for diabetes? 2002.

Basu A, Betts NM, Ortiz J, Simmons B, Wu M, Lyons TJ. Low-energy cranberry juice decreases lipid oxidation and increases plasma antioxidant capacity in women with metabolic syndrome. Nutr Res. 2011;31(3):190–6.

Dohadwala MM, Holbrook M, Hamburg NM, Shenouda SM, Chung WB, Titas M, et al. Effects of cranberry juice consumption on vascular function in patients with coronary artery disease. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011;93(5):934–40.

Novotny JA, Baer DJ, Khoo C, Gebauer SK, Charron CS. Cranberry juice consumption lowers markers of cardiometabolic risk, including blood pressure and circulating C-reactive protein, triglyceride, and glucose concentrations in adults. J Nutr. 2015;145(6):1185–93.

Shidfar F, Heydari I, Hajimiresmaiel SJ, Hosseini S, Shidfar S, Amiri F. The effects of cranberry juice on serum glucose, apoB, apoA-I, Lp(a), and Paraoxonase-1 activity in type 2 diabetic male patients. J Res Med Sci. 2012;17(4):355–60.

Flammer AJ, Martin EA, Gössl M, Widmer RJ, Lennon RJ, Sexton JA, et al. Polyphenol-rich cranberry juice has a neutral effect on endothelial function but decreases the fraction of osteocalcin-expressing endothelial progenitor cells. Eur J Nutr. 2013;52(1):289–96.

Ruel G, Couillard C. Evidences of the cardioprotective potential of fruits: the case of cranberries. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2007;51(6):692–701.

Zare Javid A, Maghsoumi-Norouzabad L, Ashrafzadeh E, Yousefimanesh HA, Zakerkish M, Ahmadi Angali K, et al. Impact of cranberry juice enriched with omega-3 fatty acids adjunct with nonsurgical periodontal treatment on metabolic control and periodontal status in type 2 patients with diabetes with periodontal disease. J Am Coll Nutr. 2018;37(1):71–9.

Pourmasoumi M, Hadi A, Najafgholizadeh A, Joukar F, Mansour-Ghanaei F. The effects of cranberry on cardiovascular metabolic risk factors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Nutr. 2020;39(3):774–88.

Hormoznejad R, Mohammad Shahi M, Rahim F, Helli B, Alavinejad P, Sharhani A. Combined cranberry supplementation and weight loss diet in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease: a double-blind placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2020;71(8):991–1000.

Paquette M, Larqué ASM, Weisnagel S, Desjardins Y, Marois J, Pilon G, et al. Strawberry and cranberry polyphenols improve insulin sensitivity in insulin-resistant, non-diabetic adults: a parallel, double-blind, controlled and randomised clinical trial. Br J Nutr. 2017;117(4):519–31.

Anhê FF, Roy D, Pilon G, Dudonné S, Matamoros S, Varin TV, et al. A polyphenol-rich cranberry extract protects from diet-induced obesity, insulin resistance and intestinal inflammation in association with increased Akkermansia spp. population in the gut microbiota of mice. Gut. 2015;64(6):872–83.

Wilson T, Meyers SL, Singh AP, Limburg PJ, Vorsa N. Favorable glycemic response of type 2 diabetics to low-calorie cranberry juice. J Food Sci. 2008;73(9):H241–5.

Wilson T, Singh AP, Vorsa N, Goettl CD, Kittleson KM, Roe CM, et al. Human glycemic response and phenolic content of unsweetened cranberry juice. J Med Food. 2008;11(1):46–54.

Manning PJ, Sutherland WH, Walker RJ, Williams SM, De Jong SA, Ryalls AR, et al. Effect of high-dose vitamin E on insulin resistance and associated parameters in overweight subjects. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(9):2166–71.

Atkinson RL, Kaiser DL. Effects of calorie restriction and weight loss on glucose and insulin levels in obese humans. J Am Coll Nutr. 1985;4(4):411–9.

Esmaillzadeh A, Tahbaz F, Gaieni I, Alavi-Majd H, Azadbakht L. Concentrated pomegranate juice improves lipid profiles in diabetic patients with hyperlipidemia. J Med Food. 2004;7(3):305–8.

Chu YF, Liu RH. Cranberries inhibit LDL oxidation and induce LDL receptor expression in hepatocytes. Life Sci. 2005;77(15):1892–901.

Kahlon TS, Smith GE. In vitro binding of bile acids by blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), plums (Prunus spp.), prunes (Prunus spp.), strawberries (Fragaria X ananassa), cherries (Malpighia punicifolia), cranberries (Vaccinium macrocarpon) and apples (Malus sylvestris). Food Chem. 2007;100(3):1182–7.

Tebib K, Besançon P, Rouanet JM. Dietary grape seed tannins affect lipoproteins, lipoprotein lipases and tissue lipids in rats fed hypercholesterolemic diets. J Nutr. 1994;124(12):2451–7.

Sun Q, Yue Y, Shen P, Yang JJ, Park Y. Cranberry product decreases fat accumulation in Caenorhabditis elegans. J Med Food. 2016;19(4):427–33.

Anhê FF, Nachbar RT, Varin TV, Vilela V, Dudonné S, Pilon G, et al. A polyphenol-rich cranberry extract reverses insulin resistance and hepatic steatosis independently of body weight loss. Mol Metab. 2017;6(12):1563–73.

Peixoto TC, Moura EG, de Oliveira E, Soares PN, Guarda DS, Bernardino DN, et al. Cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon) extract treatment improves triglyceridemia, liver cholesterol, liver steatosis, oxidative damage and corticosteronemia in rats rendered obese by high fat diet. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57(5):1829–44.

Kechagias S, Nasr P, Blomdahl J, Ekstedt M. Established and emerging factors affecting the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Metabolism. 2020;111:154183.

Masuzaki R, Tateishi R, Yoshida H, Goto E, Sato T, Ohki T, et al. Comparison of liver biopsy and transient elastography based on clinical relevance. Can J Gastroenterol. 2008;22(9):753–7.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This study was funded by the liver and gastrointestinal diseases research center, Tabriz University of medical sciences, Tabriz, Iran. The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

KMS, ZN were responsible for the conception and design of the study. AMS, and ES were responsible for data acquisition. ZN were responsible for data analysis. ZN, KMS were responsible for data interpretation. ES and ZN drafted the manuscript; all other authors revised and commented on the draft. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All participants provided informed written consent. The ethics committee of Tabriz University of medical sciences approved the study protocol (Ethics code: IR.TBZMED.REC.1399.090). The study was carried out in accordance with the ethical guidelines of Tabriz University of medical sciences.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Masnadi Shirazi, K., Shirinpour, E., Masnadi Shirazi, A. et al. Effect of cranberry supplementation on liver enzymes and cardiometabolic risk factors in patients with NAFLD: a randomized clinical trial. BMC Complement Med Ther 21, 283 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03436-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-021-03436-6