Abstract

Background

The variation in breast cancer incidence rates across different regions may reflect disparities in breast cancer screening (BCS) practices. Understanding the factors associated with these screening behaviors is crucial for identifying modifiable elements amenable to intervention. This systematic review aims to identify common factors influencing BCS behaviors among women globally.

Methods

Relevant papers were sourced from PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar. The included studies were published in English in peer-reviewed journals from January 2000 to March 2023 and investigated factors associated with BCS behaviors.

Results

From an initial pool of 625 articles, 34 studies (comprising 29 observational and 5 qualitative studies) with 36,043 participants were included. Factors influencing BCS behaviors were categorized into nine groups: socio-demographic factors, health status history, knowledge, perceptions, cultural factors, cues to action, motivation, self-efficacy, and social support. The quality appraisal scores of the studies ranged from average to high.

Conclusions

This systematic review highlights factors pivotal for policy-making at various levels of breast cancer prevention and assists health promotion professionals in designing more effective interventions to enhance BCS practices among women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Breast cancer stands as the most commonly diagnosed cancer among women worldwide, affecting both developed and developing countries [1]. Statistical analyses indicate that while wealthier nations report higher breast cancer incidence rates, less developed countries suffer from higher relative mortality rates [2].

In high-income countries, including the United Kingdom, Australia, and Eastern Europe, over 60% of women are diagnosed at stages one and two of the disease, significantly improving their survival rates. Conversely, women in low-income countries often seek treatment at advanced disease stages when it has metastasized to other organs [3].

Differences in cancer incidence rates across populations may be attributable to the variance in risk factor prevalence and the implementation or uptake of screening programs [4].

Routine screening is pivotal in detecting breast cancer at an early, more treatable stage, significantly reducing mortality rates [5]. The primary methods of screening include breast self-examination (BSE), clinical breast examination (CBE) by a healthcare professional, and mammography (MMG), all of which have been demonstrated to lower mortality rates from breast cancer in various studies [6,7,8,9].

Despite numerous interventions and educational efforts aimed at promoting participation in BCS programs, recent studies indicate a continuing rise in mortality rates and a persistently low participation rate among women, particularly in less developed countries [1, 10]. For instance, recent figures show that only 13.6% of Malaysian, 0.3% of Egyptian, and 3.8% of Ethiopian women have undergone MMG in the past two years, compared to 81%, 88%, and 70% in Belgium, Australia, and the United States, respectively [11,12,13,14,15,16]. These disparities highlight the crucial need for developing and implementing effective strategies based on scientific and reliable research to enhance screening behaviors across different societies.

Given the significance of BCS and the dire predictions that both morbidity and mortality from breast cancer will more than double by 2035 [3], it becomes imperative to conduct a comprehensive review of the published literature. This systematic review aims to [1] summarize current knowledge on factors influencing BCS behaviors and [2] identify factors relevant to enhancing screening behaviors among women worldwide. Achieving these objectives and leveraging the findings of this research could empower policymakers, researchers, and health promotion professionals to devise more effective prevention policies and interventions, thereby improving BCS behaviors through well-informed strategies.

Methods

This systematic review was registered with PROSPERO under the registration number CRD42023432810. The presentation of findings adheres to the PRISMA checklist standards (Additional file 1).

Search Strategy

The research question, structured according to the PICOS framework, was: “What are the factors impacting BCS behaviors among women worldwide?”

The PICOS elements defined were as follows:

-

Population: Healthy individuals aged 15 years or older, encompassing all genders, races, and geographic locations.

-

Intervention (Influential Factors): This includes socio-demographic factors, health history, knowledge, perceptions, cultural factors, cues to action, motivation, self-care, and social support.

-

Comparison Group: Subpopulations and subgroups differentiated by socio-demographic variables.

-

Outcome: Practices related to BCS.

-

Study Design: The review included cross-sectional, retrospective, prospective, and qualitative studies.

Four key search concepts and their synonyms (Table 1) were identified for the search. The international databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, Science Direct, Embase, and Google Scholar. Berenguer and Sakellariou’s search strategy [17] was adopted. The search concepts, along with their synonyms (utilizing truncations and wildcards, as indicated in Tables 1 and Additional file 2), where the asterisk ‘*’ was applied where appropriate, and subject heading terms were combined using the Boolean operators ‘OR’ within concepts, and ‘AND’ to combine concepts, thus developing the final search strategy (Additional file 2).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they:

-

1.

Reported on MMG, CBE, or BSE as methods for BCS, in alignment with recommendations by international health organizations.

-

2.

Were published in peer-reviewed journals between January 2000 and March 2023.

-

3.

Addressed factors associated with BCS behaviors, focusing on associated factors rather than the effects of interventions.

-

4.

Employed quantitative or qualitative research designs.

-

5.

Included participants aged 15 years or older.

The exclusion criteria for the studies were:

-

1.

Duplicate publications across databases.

-

2.

Non-original research articles, including dissertations, reviews, case reports, editorials, oral and poster presentations, and book chapters.

-

3.

Publications in languages other than English.

-

4.

Preprints are not subjected to peer review.

-

5.

Studies focusing on general cancer screening are not specific to breast cancer.

-

6.

The research concentrated on other preventative behaviors or early detection methods unrelated to BCS.

-

7.

Studies focused on factors associated with the second BCS participation round.

-

8.

Research involving women with specific conditions, such as those who are sick or vulnerable.

Study selection

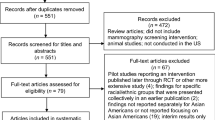

The selection followed PRISMA guidelines. Initially, duplicates across databases were removed. Titles and abstracts were then reviewed for relevance, and articles not meeting the inclusion criteria were discarded. Subsequently, full texts of the remaining studies were evaluated for relevance, with any further non-compliant studies excluded. This review process was independently conducted by two researchers, with any discrepancies resolved through discussion.

Quality assessment

Following numerous academics’ recommendations, the methodological quality of the included studies was assessed, and a Methodological Quality Score (MQS) was assigned. Experts evaluated each study’s conceptual and methodological rigor, resolving discrepancies by consensus. Based on Bernstein’s standards [18] and as explained by Patton [19], the assessment criteria included theoretical framework usage, study design, sample size, measurement instruments, data analysis, and reporting on reliability and validity. Quantitative studies were scored on a scale from 0 to 19, and qualitative studies from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating higher methodological quality. Studies scoring below 60% were excluded.

Data extraction and synthesis

Data were independently extracted by two researchers (BT and HSH), using a pre-designed tool to collect methodological details, including first author, publication year, study design, data source, study location, sampling strategy, sample size, data collection techniques, participant age, BCS method, and conceptual framework. For quantitative studies, additional data on screening participation rates and identified factors associated with BCS behaviors were noted. Qualitative studies included thematic information extracted for analysis.

Results

An initial search yielded 625 articles from the specified databases. After removing duplicates and screening titles and abstracts, 118 papers were selected for full-text evaluation. Ultimately, 34 papers comprising 29 observational studies and 5 qualitative studies, with 36,043 participants, were included in the final review. The study selection process is illustrated in Fig. 1.

Quality of included studies

None of the studies achieved the highest possible score. A majority of the studies were cross-sectional designs (82.4%), and over half (64.7%) included large samples (more than 300 participants). Furthermore, 67.7% of the studies grounded their findings in specific theoretical frameworks. Approximately half reported the psychometric properties of their assessment instruments. A significant portion (85.3%, N = 29) of the studies were quantitative and utilized both descriptive and advanced statistical analyses, such as t-tests, multiple regression, logistic regression, and multivariate analysis. The qualitative studies (14.7%, N = 5) primarily employed content and thematic analysis. All quantitative studies assessed the statistical significance of factors associated with BCS behaviors (Table 2).

Characteristics of included studies

The 34 articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria were geographically diverse: 20 studies were conducted in Asia [10, 11, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37], 5 in America [16, 38,39,40,41], 4 in Europe [14, 42,43,44], 4 in Africa [12, 13, 45, 46], and 1 in Australia [15].

The sample sizes ranged from 8 to 11,409 participants, with the age of participants spanning from 15 to 82 years. Except for one qualitative study focusing on Arab men’s perceptions of female BCS [34], all participants were women.

There was variability in the BCS methods and the measurement of related factors across studies. Eleven studies identified CBE, BSE, or MMG as the screening methods [13, 20, 22, 29, 30, 32, 34, 36, 37, 41, 46]; four defined BSE or MMG [12, 25, 31, 35]; one mentioned CBE or MMG [11]; one mentioned CBE or BSE [24]; one specified CBE alone [39]; six identified BSE alone [23, 26, 28, 33, 45, 47]; and ten focused solely on MMG [14,15,16, 27, 38, 40, 42,43,44, 48].

The reported BCS rates varied significantly across studies, from 0.3 to 62% for BSE, 2.5–41% for CBE, and 0.3–88.1% for MMG (Table 3).

Factors associated with BCS behaviors

The question of “What factors impact BCS behaviors in women worldwide?” is comprehensively answered through the analysis presented in Tables 4, 5 and 6. These tables delineate the factors influencing BSE, CBE, and MMG, respectively, as identified in the 34 reviewed articles.

The factors identified are categorized into nine key areas:

-

1.

Socio-demographic Factors: This includes age, education level, income, marital status, and employment status, highlighting how these variables influence screening behaviors.

-

2.

Health History: Past health experiences, family history of breast cancer, and personal health beliefs play a significant role in an individual’s decision to undergo screening.

-

3.

Knowledge: The awareness and understanding of breast cancer and the benefits of early detection through screening methods.

-

4.

Perceptions: Women’s beliefs and attitudes towards breast cancer risk, the effectiveness of screening, and the healthcare system’s role in cancer detection.

-

5.

Cultural Factors: How cultural beliefs, norms, and societal expectations shape attitudes towards breast health and screening practices.

-

6.

Cues to Action: External prompts, such as recommendations from healthcare professionals, health campaigns, or peers’ experiences, encourage women to seek screening.

-

7.

Motivation: The intrinsic and extrinsic motivators drive women to participate in screening activities.

-

8.

Self-care: The degree to which women prioritize their health and well-being, including the proactive pursuit of health screenings.

-

9.

Social Support: The influence of family, friends, and community networks in supporting or hindering screening behaviors.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to identify the universal factors influencing BCS behaviors among women globally. Although most countries offer BCS programs [17], the nature and implementation of these programs vary significantly across different health systems and populations [49]. Consequently, the BCS methods examined in this review varied, reflecting these disparities. MMG, recognized for its efficacy in clinical studies, is predominantly used in developed countries due to its higher costs [8]. Conversely, in developing countries, BSE stands out as a widely adopted, cost-effective method for early detection [50].

Moreover, the rates of screening methods reported in the literature show considerable international variation. Countries like Sweden, Belgium, the USA, and Australia report high MMG screening rates [14,15,16, 43], whereas BSE is more prevalent in countries like Egypt, Ethiopia, Turkey, Iran, and Iraq [12, 13, 25, 26, 32], often falling below the WHO’s recommended screening rates [49].

The WHO underscores the importance of high participation rates in screening programs to enhance their effectiveness [49]. Understanding the factors influencing participation enables health systems to adopt comprehensive strategies for prevention, early diagnosis, and BCS promotion.

Over half of the studies reviewed focused on socio-demographic factors as determinants of screening behaviors, identified in previous research as facilitators and barriers [51, 52]. Findings indicate that demographic variables such as age, education level, income, and employment status significantly influence screening rates.

While socio-demographic status is recognized as a crucial determinant of access to BCS in both high-income [51, 52] and middle-income countries [10, 17], studies in European countries with organized screening programs report no correlation between screening participation and socio-demographic variables [53]. A 2011 study exploring the impact of socioeconomic inequalities on screening participation highlighted that such disparities exist even without financial barriers [54]. These variations necessitate careful interpretation, considering women’s diverse challenges in accessing screening services worldwide, including geographical, economic, and cultural obstacles.

For instance, despite Qatar’s provision of comprehensive medical services at no cost, including BCS, cultural barriers have led to only a third of eligible women utilizing these services [34]. Thus, offering organized screening programs with equitable access could gradually mitigate socioeconomic disparities.

The review also highlights that beyond a family history of breast cancer and personal breast health issues, fertility-related challenges, such as infertility and hormonal imbalances, influence screening behaviors. This finding aligns with systematic reviews from China and the USA, which examined screening factors among different populations [55, 56]. Women with personal or familial health histories may perceive a higher susceptibility to breast cancer, thereby increasing their utilization of healthcare services for screening and diagnostic tests. This heightened awareness and concern about breast cancer risk can motivate women to adopt preventive measures, including screening. However, it is notable that many women may not pursue screening until symptomatic or following the discovery of breast cancer in close relatives [57, 58].

The findings of the study reveal that women with comprehensive knowledge about breast cancer risk factors, symptoms, and screening methods are more likely to participate in screening programs. Conversely, women who have not undergone screening often lack awareness or believe that once screened, repeat screenings are unnecessary [59]. This lack of knowledge has been identified as a critical barrier to screening participation among Iranian and Asian women and as a predictive factor for the late diagnosis of breast cancer in Canada [10, 60, 61]. However, Schlueter’s study found no correlation between the level of knowledge and screening behaviors [62], indicating the complexity of this relationship.

Educational interventions targeting breast cancer awareness and screening guidelines are crucial for improving women’s knowledge and participation rates.

Perceptual factors significantly influence screening behaviors, including fewer perceived barriers and higher self-efficacy. A Chinese study highlighted reduced perceived barriers as a predictive factor for screening participation [55]. Main barriers identified include fear [34, 42, 46, 48], anxiety [29, 30], worry [22, 63], religious beliefs and fatalism [32, 46, 48], financial constraints [34], language barriers [29, 39, 40], and embarrassment [63]. Although fear can motivate screening behavior in some contexts [56], it is predominantly an emotional barrier in the findings.

Types of fear recognized include the fear of mastectomy, diagnosis of cancer, and stigmatization [34, 46, 48]. Consedine et al. noted that while fear of cancer could facilitate screening, specific fears—such as those associated with medical procedures or diagnosis—often deter women from participating [64]. A meta-analysis further linked fear of breast cancer to screening behaviors [65], suggesting that mitigating fear through education and positive screening experiences could enhance participation rates.

Cultural factors, particularly religious beliefs, and fatalism, notably impact screening behaviors. Some Muslim women believe BCS is unnecessary, viewing cancer as a divine challenge or part of destiny [63]. This fatalistic view, a belief in the health locus of control being external (chance or divine will), can lead to passive health behaviors [66]. While some studies show no significant impact of religious beliefs on screening behaviors [67], the intertwined nature of these beliefs with culture and religion necessitates nuanced interventions.

Effective strategies might involve integrating breast cancer awareness and early diagnosis information within the framework of existing belief systems leveraging religious leaders to promote health messages aligned with spiritual teachings. Such approaches, using religious and spiritual elements in health messaging, have been shown to encourage screening behaviors among women [11].

The results of this review highlight that women are more likely to engage in BCS behaviors when they receive information from healthcare teams, social media, or other sources compared to those who do not consult with healthcare professionals or use social media for health information. Jones et al. emphasized that recommendations and reminders from healthcare providers are among the most effective means of directing women toward MMG and other screening tests [68]. A 2019 study further showed that ignoring cues to action, such as letters, messages, and reminder calls, correlates with lower MMG participation rates [69].

In the modern era, widespread access to information through digital media, advancements in technology, and the introduction of electronic health tools have facilitated the use of these platforms in cancer screening campaigns. For instance, smartphone applications that remind users about screening schedules and provide preventive advice through text, images, and videos represent an innovative approach to enhancing screening participation.

This review also underscores a significant link between motivation and BCS behaviors. Khazaee-Pool et al. found that motivational solid factors, such as valuing life and health responsibility, significantly encourage screening participation [21]. Moreover, studies among diverse racial and ethnic groups have identified a clear association between motivation and increased screening activities [70].

Various socio-psychological barriers, including attitudes, cultural beliefs, and communication issues, have been identified as impediments to motivation [71]. Factors contributing to low motivation for MMG include the perceived unimportance of testing, lack of support, time constraints, cost concerns, familial obligations, and a busy lifestyle [48]. Therefore, interventions aimed at enhancing motivational self-efficacy could significantly improve screening participation.

As part of self-care practices, regular health check-ups have been shown to predict screening behaviors. Reviews have highlighted a correlation between infrequent mammograms and breast exams among Asian and Korean-American women with irregular gynecological visits [51, 59]. Although MMG can be performed without direct referrals in some countries [59], the lack of commitment to regular check-ups remains a barrier. As Pasket et al. reported, while 75% of women acknowledged the importance of periodic exams, 67% indicated that their physicians did not actively encourage MMG [72].

Improving knowledge about self-care and self-regulation is crucial for fostering regular health examination habits. The health system’s role in scheduling periodic health assessments and encouraging adherence is also vital, as demonstrated by research from the Netherlands, which linked pre-scheduled appointments and proactive general practitioner involvement to higher screening rates [49].

Regarding social support, assistance from healthcare teams and family members significantly influences screening behaviors. Lack of partner support and fear of familial disruption post-diagnosis have been noted as significant barriers among African-American women [68]. Support from family and friends, providing both financial and emotional backing, can bolster confidence, reduce fear, and encourage screening participation [21, 59, 73].

The review also points out that women’s financial independence and employment status in certain regions are critical in health decision-making. Conversely, many women rely on male family members to make health decisions, a group that requires targeted support from health teams for emotional, instrumental, and informational needs. Leong et al. found that social support not only reduces depression but also promotes healthier behaviors [74]. Thus, establishing support networks and self-help groups can enhance women’s knowledge, experience, and motivation regarding BCS, ultimately fostering a community of mutual encouragement and support.

Strengths

This systematic review meticulously evaluated the quality of included studies to ensure their reliability and relevance. A unique aspect of the analysis is the consideration of men’s attitudes and perceptions toward BCS, acknowledging the influence of gender dynamics on screening behaviors. A comprehensive approach was undertaken, analyzing factors affecting BCS behaviors across quantitative and qualitative studies and categorizing them based on their impact on three distinct screening behaviors: BSE, CBE, and MMG. This nuanced categorization provides a detailed understanding of the diverse influences on BCS practices.

Limitations

This research was confined to online studies, potentially overlooking valuable research indexed in databases such as PubMed, Scopus, Embase, and Google Scholar or available only in print. The restriction to English-language publications may have excluded pertinent non-English studies, introducing language bias. The review’s predominance of cross-sectional studies limits the ability to ascertain causal relationships between the factors studied and screening behaviors. Additionally, the reliance on self-reported data raises concerns about the accuracy of the findings, given the potential for recall bias or the desire of participants to present themselves in a socially desirable light.

The heterogeneity of the included studies—in terms of study design, geographic location, methodological approach, demographic characteristics, sample size, screening methods employed, and the intervals between screenings—complicates direct comparisons and may affect the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusion

This systematic review synthesizes a broad array of research on the factors influencing BCS behaviors among women worldwide. By examining various screening methods and participation rates, along with identifying determinants of screening behavior, this study contributes valuable insights to the field of public health. The findings highlight the complex interplay of factors affecting screening behaviors and provide evidence-based guidance for policymakers and health promotion professionals. This knowledge is crucial for developing targeted interventions that can effectively encourage BCS practices, ultimately contributing to breast cancer prevention and early detection.

Availability of data and materials

This published article and its supplementary information files include all data generated or analyzed during this study.

Abbreviations

- BCS:

-

Breast cancer screening

- BSE:

-

Breast self-examination

- CBE:

-

Clinical breast examination

- MMG:

-

Mammography

- MQS:

-

Methodological quality score

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Torre LA, Islami F, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer in women: burden and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Prev Biomarkers. 2017;26(4):444–57. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-99.

Azamjah N, Soltan-Zadeh Y, Zayeri F. Global Trend of Breast Cancer Mortality Rate: A 25-Year Study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2019/07/28. 2019;20(7):2015–20. https://doi.org/10.31557/apjcp.2019.20.7.2015.

Ghoncheh M, Pournamdar Z, Salehiniya H. Incidence and Mortality and Epidemiology of Breast Cancer in the World. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016/05/12. 2016;17(S3):43–6. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2016.17.s3.43.

Sopik V. International variation in breast cancer incidence and mortality in young women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2021;186(2):497–507. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10549-020-06003-8.

Conway-Phillips R, Janusek L. Influence of sense of coherence, spirituality, social support and health perception on breast cancer screening motivation and behaviors in African American women. ABNF J. 2014;25(3). Retrieved from http://www.ABNF.Journal.com/.

Screening PD, Board PE. Breast Cancer Screening (PDQ®). InPDQ Cancer Information Summaries [Internet]. National Cancer Institute (US); 2023.

Screening PDQ, Prevention Editorial B. Breast Cancer screening (PDQ®): Health Professional Version. In: PDQ Cancer Information Summaries. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute (US); 2002.

Austoker J. Cancer Prevention in Primary Care: screening and self examination for breast cancer. BMJ. 1994;309(6948):168–74. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.309.6948.168.

Ahmad A. Breast Cancer Statistics: Recent Trends. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019/08/29. 2019;1152:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20301-6_1.

Ahmadian M, Samah AA. A literature review of factors influencing breast cancer screening in Asian countries. Life Sci J. 2012;9:585–94. Retrieved from http://www.lifesciencesite.com/.

Parsa P, Kandiah M. Predictors of adherence to clinical breast examination and mammography screening among Malaysian women. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2010;11(3):681–8.

Hassan EE, Seedhom AE, Mahfouz EM. Awareness about breast cancer and its screening among rural Egyptian women, Minia District: a population-based study. Asian Pac J cancer Prev APJCP. 2017;18(6):1623. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2017.18.6.1623.

Abeje S, Seme A, Tibelt A. Factors associated with breast cancer screening awareness and practices of women in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Womens Health. 2019;19(1):4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0695-9.

Schoofs J, Krijger K, Vandevoorde J, Devroey D. Health-related factors associated with adherence to breast cancer screening. J Midlife Health. 2017;8(2):63. https://doi.org/10.4103/jmh.JMH_71_15.

Carey RN, El-Zaemey S. Lifestyle and occupational factors associated with participation in breast mammography screening among western Australian women. J Med Screen. 2020;27(2):77–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969141319878747.

Jin SW, Lee HY, Lee J. Analyzing factors of breast cancer screening adherence among Korean American women using Andersen’s behavioral model of healthcare services utilization. Ethn Dis. 2019;29(Suppl 2):427. https://doi.org/10.18865/ed.29.S2.427.

Nuche-Berenguer B, Sakellariou D. Socioeconomic determinants of cancer screening utilisation in Latin America: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(11):e0225667. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225667.

Bernstein IN. In: Freeman HE, editor. Academic and entrepreneurial research: consequences of diversity in federal evaluation studies. Russell Sage Foundation; 1975. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7758/9781610448253.

Patton MQ. Utilization-focused evaluation: the new century text, 3rd edn Sage. Thousand Oaks; Google Sch. 1997.

Kardan-Souraki M, Moosazadeh M, Khani S, Hamzehgardeshi Z. Factors related to breast cancer screening in women in the northern part of Iran: a cross-sectional study. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2019;7(4):637. https://doi.org/10.3889/oamjms.2019.045.

Khazaee-Pool M, Montazeri A, Majlessi F, Foroushani AR, Nedjat S, Shojaeizadeh D. Breast cancer-preventive behaviors: exploring Iranian women’s experiences. BMC Womens Health. 2014;14(1):41. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-41.

Moghaddam ES, Shahnazi H, Hassanzadeh A. Predictive power of PEN-3 model constructs in breast Cancer screening behaviors among teachers: a cross-sectional study in Central Iran. Eur J Breast Heal. 2019;15(2):105. https://doi.org/10.5152/ejbh.2019.4417.

Moh Myint NM, Nursalam N, Mar’ah Has EM. Exploring the Influencing Factors on Breast Self-Examination Among Myanmar Women: A Qualitative Study. Jurnal Ners. 2020;15(1):85. https://e-journal.unair.ac.id/JNERS/article/view/18863.

Safarpour M, Tiyuri A, Mohamadzade M, Knowledge. Attitudes and practice of women towards breast Cancer and its screening: Babol City, Iran–2017. Iran J Heal Sci. 2018. https://doi.org/10.18502/jhs.v6i4.199.

Secginli S, Nahcivan NO. Factors associated with breast cancer screening behaviours in a sample of Turkish women: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(2):161–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.004.

Shakor JK, Mohammed AK, Karotia D. Determinants of breast self-examination practice amongst Iraqi/Sulaimani Women using Champion Health belief model and breast CAM. Int J Med Res Heal Sci. 2019;8(9):51–9. Retrieved from. https://www.ijmrhs.com.

Tabrizi FM, Vahdati S, Khanahmadi S, Barjasteh S. Determinants of breast cancer screening by mammography in women referred to health centers of Urmia, Iran. Asian Pac J cancer Prev APJCP. 2018;19(4):997. https://doi.org/10.22034/APJCP.2018.19.4.997.

Tavafian SS, Hasani L, Aghamolaei T, Zare S, Gregory D. Prediction of breast self-examination in a sample of Iranian women: an application of the Health Belief Model. BMC Womens Health. 2009;9(1):37. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-9-37.

Thomas E, Escandón S, Lamyian M, Ahmadi F, Setoode SM, Golkho S. Exploring Iranian women’s perceptions regarding control and Prevention of breast Cancer. Qual Rep. 2011;16(5):1214–29. https://doi.org/10.46743/2160-3715/2011.1295.

Çam O, Gümüs AB. Breast cancer screening behavior in Turkish women: relationships with health beliefs and self-esteem, body perception and hopelessness. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10(1):49–56. http://journal.waocp.org/article_24873.html.

Canbulat N, Uzun Ö. Health beliefs and breast cancer screening behaviors among female health workers in Turkey. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(2):148–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2007.12.002.

Charkazi A, Samimi A, Razzaghi K, Kouchaki GM, Moodi M, Meirkarimi K, et al. Adherence to recommended breast cancer screening in Iranian Turkmen women: the role of knowledge and beliefs. ISRN Prev Med. 2013;2013. https://doi.org/10.5402/2013/581027.

Dewi TK, Massar K, Ruiter RAC, Leonardi T. Determinants of breast self-examination practice among women in Surabaya, Indonesia: an application of the health belief model. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7951-2.

Donnelly TT, Al-Khater A-H, Al-Bader SB, Al-Kuwari MG, Abdul Malik MA, Al-Meer N, et al. Perceptions of arab men regarding female breast cancer screening examinations—findings from a Middle East study. PLoS ONE. 2017;12(7):e0180696. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0180696.

Fouladi N, Pourfarzi F, Mazaheri E, Asl HA, Rezaie M, Amani F, et al. Beliefs and behaviors of breast cancer screening in women referring to health care centers in northwest Iran according to the champion health belief model scale. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14(11):6857–62. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2013.14.11.6857.

Hajian-Tilaki K, Auladi S. Health belief model and practice of breast self-examination and breast cancer screening in Iranian women. Breast Cancer. 2014;21(4):429–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12282-012-0409-3.

Harirchi I, Azary S, Montazeri A, Mousavi SM, Sedighi Z, Keshtmand G, et al. Literacy and breast cancer prevention: a population-based study from Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2012;13(8):3927–30. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.8.3927.

Moreira CB, Fernandes AFC, Castro RCMB, de Oliveira RDP, Pinheiro AKB. Social determinants of health related to adhesion to mammography screening. Rev Bras Enferm. 2018;71(1):97–103. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2016-0623.

Ahmad F, Stewart DE. Predictors of clinical breast examination among south Asian immigrant women. J Immigr Health. 2004;6(3):119–26. https://doi.org/10.1023/b:joih.0000030227.41379.13.

Ma GX, Gao W, Lee S, Wang M, Tan Y, Shive SE. Health seeking behavioral analysis associated with breast cancer screening among Asian American women. Int J Womens Health. 2012;4:235. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S30738.

Racine L, Andsoy I, Maposa S, Vatanparast H, Fowler-Kerry S. Examination of breast cancer screening knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs among Syrian refugee women in a western Canadian province. Can J Nurs Res. 2022;54(2):177–89. https://doi.org/10.1177/08445621211013200.

Marmarà D, Marmarà V, Hubbard G. Health beliefs, illness perceptions and determinants of breast screening uptake in Malta: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):416. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4324-6.

Lagerlund M, Drake I, Wirfält E, Sontrop JM, Zackrisson S. Health-related lifestyle factors and mammography screening attendance in a Swedish cohort study. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2015;24(1):44–50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48504405.

Bailly L, Jobert T, Petrovic M, Pradier C. Factors influencing participation in breast cancer screening in an urban setting. A study of organized and individual opportunistic screening among potentially active and retired women in the city of Nice. Prev Med Rep. 2023;31:102085. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2022.102085.

Kangmennaang J, Mkandawire P, Luginaah I. Breast cancer screening among women in Namibia: explaining the effect of health insurance coverage and access to information on screening behaviours. Glob Health Promot. 2019;26(3):50–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975917727017.

Elewonibi B, BeLue R. The influence of socio-cultural factors on breast cancer screening behaviors in Lagos, Nigeria. Ethn Health. 2019;24(5):544–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2017.1348489.

Ahmadian M, Carmack S, Samah AA, Kreps G, Saidu MB. Psychosocial predictors of breast self-examination among female students in Malaysia: a study to assess the roles of body image, self-efficacy and perceived barriers. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(3):1277–84. https://doi.org/10.7314/APJCP.2016.17.3.1277.

Khazaee-pool M, Majlessi F, Foroushani AR, Montazeri A, Nedjat S, Shojaeizadeh D, et al. Perception of breast cancer screening among Iranian women without experience of mammography: a qualitative study. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(9):3965–71. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.9.3965.

Bongaerts THG, Büchner FL, Middelkoop BJC, Guicherit OR, Numans ME. Determinants of (non-) attendance at the Dutch cancer screening programmes: a systematic review. J Med Screen. 2020;27(3):121–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969141319887996.

Akhtari-Zavare M, Ghanbari Baghestan A, Latiff LA, Matinnia N, Hoseini M. Knowledge of breast cancer and breast self-examination practice among Iranian women in Hamedan, Iran. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:6531–4. https://doi.org/10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.16.6531.

Oh KM, Taylor KL, Jacobsen KH. Breast cancer screening among Korean americans: a systematic review. J Community Health. 2017;42(2):324–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0258-7.

Pruitt SL, Shim MJ, Mullen PD, Vernon SW, Amick BC III. Association of area socioeconomic status and breast, cervical, and colorectal cancer screening: a systematic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(10):2579–99. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.epi-09-0135.

Gianino MM, Lenzi J, Bonaudo M, Fantini MP, Siliquini R, Ricciardi W, et al. Organized screening programmes for breast and cervical cancer in 17 EU countries: trajectories of attendance rates. BMC Public Heal 2018 181. 2018;18(1):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/S12889-018-6155-5.

Aarts MJ, Voogd AC, Duijm LEM, Coebergh JWW, Louwman WJ. Socioeconomic inequalities in attending the mass screening for breast cancer in the south of the Netherlands—associations with stage at diagnosis and survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128(2):517–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10549-011-1363-z.

Wu Z, Liu Y, Li X, Song B, Ni C, Lin F. Factors associated with breast cancer screening participation among women in mainland China: a systematic review. BMJ Open. 2019;9(8):e028705. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028705.

Orji CC, Kanu C, Adelodun AI, Brown CM. Factors that influence mammography use for breast cancer screening among African American women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2020;112(6):578-92.

Rasool S, Iqbal M, Siddiqui A, Ahsan R, Mukhtar S, Naqvi S, Knowledge. Attitude, practice towards breast Cancer and breast self-examination among female undergraduate students in Karachi, Pakistan. J Adv Med Med Res. 2019;1–11. https://doi.org/10.9734/jammr/2019/v29i930126.

de Cuevas RMA, Saini P, Roberts D, Beaver K, Chandrashekar M, Jain A, et al. A systematic review of barriers and enablers to south Asian women’s attendance for asymptomatic screening of breast and cervical cancers in emigrant countries. BMJ Open. 2018;8(7):e020892. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020892.

Parsa P, Kandiah M, Abdul Rahman H, Mohd Zulkefli NA. Barriers for breast cancer screening among Asian women: a mini literature review. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2006;7(4):509–14. Retrieved from https://d1wqtxts1xzle7.cloudfront.net/42564309/.

Babu GR, Samari G, Cohen SP, Mahapatra T, Wahbe RM, Mermash S et al. Breast cancer screening among females in Iran and recommendations for improved practice: a review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2011;12(7):1647–55. Retrieved from http://journal.waocp.org/article_25752.html.

Webber C, Jiang L, Grunfeld E, Groome PA. Identifying predictors of delayed diagnoses in symptomatic breast cancer: a scoping review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2017;26(2):e12483. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12483.

Schlueter LA. Knowledge and beliefs about breast cancer and breast self-examination among athletic and nonathletic women. Nursing research. 1982;31(6):348-53.

Khazaee-Pool M, Majlessi F, Montazeri A, Pashaei T, Gholami A, Ponnet K. Development and psychometric testing of a new instrument to measure factors influencing women’s breast cancer prevention behaviors (ASSISTS). BMC Womens Health. 2016;16(1):40. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-016-0318-2.

Consedine NS, Magai C, Krivoshekova YS, Ryzewicz L, Neugut AI, Fear. Anxiety, Worry, and Breast Cancer Screening Behavior: A Critical Review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2004;13(4):501–10. https://aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/13/4/501/168633/Fear-Anxiety-Worry-and-Breast-Cancer-Screening. https://doi.org/10.1158/1055-9965.501.13.4.

Hay JL, McCaul KD, Magnan RE. Does worry about breast cancer predict screening behaviors? A meta-analysis of the prospective evidence. Prev Med (Baltim). 2006;42(6):401–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.03.002.

Wallston KA, Strudler Wallston B, DeVellis R. Development of the multidimensional health locus of control (MHLC) scales. Health Educ Monogr. 1978;6(1):160–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/109019817800600107.

Montazeri A, Vahdaninia M, Harirchi I, Harirchi AM, Sajadian A, Khaleghi F, et al. Breast cancer in Iran: need for greater women awareness of warning signs and effective screening methods. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2008;7(1):1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1447-056X-7-6.

Jones CEL, Maben J, Jack RH, Davies EA, Forbes LJL, Lucas G, et al. A systematic review of barriers to early presentation and diagnosis with breast cancer among black women. BMJ Open. 2014;4(2):e004076. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004076.

Marmarà D, Marmarà V, Hubbard G. Predicting reattendance to the second round of the Maltese national breast screening programme: an analytical descriptive study. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):189. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-6507-9.

Talley CH, Yang L, Williams KP. Breast cancer screening paved with good intentions: application of the information–motivation–behavioral skills model to racial/ethnic minority women. J Immigr Minor Heal. 2017;19(6):1362–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-016-0355-9.

Andreeva VA, Pokhrel P. Breast cancer screening utilization among eastern European immigrant women worldwide: a systematic literature review and a focus on psychosocial barriers. Psycho-oncology. 2013;22(12):2664–75. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3344.

Paskett ED, Tatum CM, Mack DW, Hoen H, Case LD, Velez R. Validation of self-reported breast and cervical cancer screening tests among low-income minority women. Cancer Epidemiol biomarkers Prev a Publ Am Assoc Cancer Res cosponsored by Am Soc Prev Oncol. 1996;5(9):721–6. Retrieved from https://www.aacrjournals.org/cebp/article/5/9/721/154431/.

Alexandraki I, Mooradian AD. Barriers related to mammography use for breast cancer screening among minority women. J Natl Med Assoc. 2010;102(3):206–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0027-9684(15)30527-7.

Leung J, Pachana NA, McLaughlin D. Social support and health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer: a longitudinal study. Psychooncology. 2014;23(9):1014–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.3523.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences and the Isfahan School of Health for their support. Our thanks also go to all who contributed to the conceptualization, execution, and analysis of this work.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.T. and H.S. conceived the project; B.T. and H.S. performed the literature search; all authors contributed to the literature analysis and synthesis of data; F.Z. and A.F. created the figures and tables; B.T. and H.S. wrote the review. All authors were involved in further editing and finalizing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This manuscript received ethical approval from the Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Science code: 3400585; Ethical Code: IR.MUI.RESEARCH.REC.1400.343). Given the nature of this systematic review, consent to participate was not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tavakoli, B., Feizi, A., Zamani-Alavijeh, F. et al. Factors influencing breast cancer screening practices among women worldwide: a systematic review of observational and qualitative studies. BMC Women's Health 24, 268 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03096-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-024-03096-x