Abstract

Background

Fertility desire is one of the predictors of contraceptive behavior and fertility-related outcomes. However, information is scarce on individual and community-level factors of women’s fertility decisions in sub-Saharan Africa.

Objective

To assess fertility decisions and their associated factors in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Methods

The 35 Sub-Saharan African country’s most recent demographic and health surveys (DHS) data conducted from 2008 to 2020 was used. A total of 284,744 (weighted) married women were used for analysis. The proportion of fertility decisions with their 95%CI was estimated. To assess the factors associated with fertility decisions, both random effect and fixed effect analyses were conducted. In the fixed analysis, particularly in the multivariable analysis, adjusted relative risk ratio (aRRR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported and variables with a p-value < 0.05 were considered significant predictors of fertility decisions.

Results

In this study, 64.35% (95%CI: 64.2%, 64.5%) of the study participants had fertility desire. However, 5.4% (95%CI: 5.3, 5.5) of the study participants had undecided fertility behavior. In the multivariable analysis, desire for more children and undecided fertility desire were relatively lower among older women, women with primary, secondary, and higher education, working women, women who currently use contraceptives, women with a higher number of living children, women with higher parity, women from eastern and southern Africa, and women from wealthy households. While, the ideal number of children, women who had decision-making autonomy, and women from the rural residence were all associated with a relatively higher desire for more children and undecided fertility desire. Furthermore, respondents' education and sex of household head were associated with the desire for more children while media exposure was associated with undecided fertility desire.

Conclusion

In this study, around two-thirds of women had a desire for more children and only 5.4% of women had undecided fertility desires. Both individual and community-level factors were associated with both desires for more children and undecided fertility desires. As a result, the aforementioned factors should be considered while developing reproductive health programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

According to the United Nations report, the global human population in the year between 2020 and 2100 may increase from 7.8 billion to 10.9 billion [1]. Around 78 million people are added to the world's population each year [2] and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) accounts for more than half of the global fertility with an estimated fertility rate of 4.8 [3, 4]. Studies revealed that economies, food production, the general environment, and the global climate will be greatly affected if the current population is increased by 40% [5,6,7]. Rapid population growth puts more pressure on already strained resources and poses a great challenge for sustainable development. Africa is responsible for greater than 50% of the projected increase in the global population by 2050. Countries of SSA, with a projected addition of greater than one billion people, account for more than 50% of the growth of the world's population in the year between 2019 and 2050 [8].

Contraceptive use is essential to achieving fertility desire and pregnancy spacing [9]. However, it is considered to be low in SSA [10]. Besides, in many SSA countries, more than half of women with a higher number of children still desire to have more children [11].

According to different studies, both individual and community levels factors such as age, marital status, income, educational level, parity, and residence are associated with fertility decisions. Besides, vast empirical evidence has confirmed that fertility decisions have a great variation across countries [12,13,14,15,16].

One of the predictors of contraceptive behavior and reproductive-related outcomes is fertility decision and understanding its magnitude has practical implications for developing family planning programs and, more broadly, for achieving the sustainable development goal [17,18,19]. Therefore, this study aimed to assess fertility decisions and associated factors in sub-Saharan Africa. Assessment of fertility desire is a very important issue to be considered and understanding the factors for the extraordinary population growth in SSA is critical for many aspects of international and national planning [20]. Besides, findings from such a multicountry study will be vital to strengthening existing measures to tackle high fertility and improvement in maternal and child health.

Methods

Study design and population

The most recent demographic and health surveys (DHS) data from 35 SSA countries, conducted between 2008 and 2020, were used. These DHS used a two-stage stratified sampling technique. A total of 284,744 (weighted) married women who had complete information on fertility decisions were used for this study (Fig. 1, Table 1). Details of the DHS methodology are reported elsewhere [21].

Study variables

Outcome variable

The outcome variable was fertility decisions. Women were asked whether they want to have a child in the future with the following options: have a desire for more children, have no desire for more children, undecided fertility desire, declared sterilized, and declared infecund. Women who declared infecund, sterilized, and with missing information were excluded because their responses were unclear about their fertility decisions. Finally, fertility decision was computed on the three responses (those who have a desire for more children, have no desire for more children, and undecided fertility desire). Then, no desire was coded as 0, desire for more children was coded as 1, and undecided fertility desire was coded as 2.

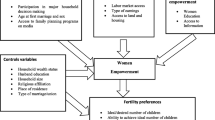

Independent variables

Independent variables were grouped into the individual-level and community-level factors. The individual-level factors included respondent age, respondent level of education, husband level of education, parity, exposure to media, current use of contraceptives, the ideal number of children, decision-making autonomy, number of living children, women employment, sex of household head, and wealth status. The community-level factors were place of residence and region of Africa (particularly SSA).

Operational definition

Media exposure

Constructed from three variables (frequency of listening to the radio, watching television, and reading newspaper/magazine). For this study, it was recoded into yes (if women were exposed to at least one media) and no (otherwise).

Decision-making autonomy

It was constructed from three variables (decision on respondent's healthcare, decision on large household purchase, and decision on visits to family or relatives) and recoded into "respondents alone" if a woman is the decision maker and "otherwise" if another person (husband, relatives, or friends) is the decision-maker [16].

Data management and statistical analyses

STATA version 16 was used for data management (extraction, recoding, and cleaning) and statistical analyses (descriptive and analytical analysis). All analyses were weighted to make the data representative, to account for the non-response rate, and to get a better statistical estimate [22]. The proportion of fertility decisions with their 95%CI was estimated and to assess the factors associated with fertility decisions, both random effect and fixed effect analyses were employed.

Fixed effect analysis

We employed a multilevel multinomial logistic regression analysis. While doing the analysis, we have fitted four models; null model, model 1, model 2, and model 3. The null model was fitted with only the outcome variable. Model 1, model 2, and model 3 were fitted using individual-level variables, community-level variables, and both individual and community-level variables respectively. To select eligible variables for the multilevel analysis, a bivariable multilevel multinomial regression was fitted first and those variables with a p-value less than 0.20 in the bivariable analysis were considered eligible. Then, in the multivariable analysis, the adjusted relative risk ratio (aRRR) with its 95% confidence interval (CI) was reported. Finally, variables with a p-value < 0.05 were considered significant predictors of fertility decisions.

Random-effect analysis

It was conducted to assess the cluster level variability of fertility decisions. Intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) and proportional change in variance (PCV) were calculated. Log-likelihood and deviance were used to verify model fitness, and a model with the highest log-likelihood and lowest deviance has been deemed as a best-fit model.

Results

Background characteristics of respondents

A total weighted sample of 284,744 married women was used for the final analysis. The mean age of the study participants was 30.82 (SD ± 8.29) years. Around two-thirds (65.74%) of the study participants were employed (workers). Most (84.99%) of women were from male-headed households and only 5.21% of women had decision-making autonomy. Around one-half, (51.73%) of women had 1–3 living children and about two-thirds of women had exposure to at least one media (Table 2).

Proportion of fertility decisions in SAA

In this study, 64.35% (95%CI: 64.2, 64.5) and 5.4% (95%CI: 5.3, 5.5) of the study participants desire more children and had undecided/undetermined fertility desires, respectively. Besides, fertility decisions had significant variation between countries and African regions (Table 3, Fig. 2).

Factors associated with fertility decisions in SSA

All variables in the bivariable analysis had p < 0.20 and were eligible for the multivariable analysis. In the multivariable multilevel multinomial analysis, age of the respondent, husband's education, employment, sex of household head, decision-making autonomy, number of living children, parity, the ideal number of children, wealth status, residence, and region of Africa were associated with both desires for more children and undecided fertility desire. Respondent’s education and sex of household head were associated with the desire for more children while media exposure was associated with undecided fertility desire only (Table 4).

Women in the age group 20–24 and 25–29 had 1.52 (aRRR = 1.52; 95%CI; 1.36, 1.71) and 1.56 (aRRR = 1.56; 95%CI; 1.39, 1.76) times higher likelihood for the desire for more children respectively as compared to women in the age group 15–19 years. However, desire for more children among women in the age group 35–39, 40–44, and 45–49 was relatively 55% (aRRR = 0.45; 95%CI; 0.40, 0.51), 83% (aRRR = 0.17; 95%CI; 0.15, 0.19), and 94% (aRRR = 0.06; 95%CI; 0.05, 0.06) lower as compared to women in the age group 15–19. The desire for more children was relatively reduced by 17% (aRRR = 0.83; 95%CI; 0.80, 0.87) and 11% (aRRR = 0.89; 95%CI; 0.85, 0.94) if a woman had primary and secondary education respectively as compared to women with no formal education. Women whom their husband have primary (aRRR = 0.81; 95%CI; 0.78, 0.84), secondary (aRRR = 0.78; 95%CI; 0.74, 0.82), and higher education (aRRR = 0.89; 95%CI; 0.83, 0.95) had relatively less desire for more children. Besides, working women (aRRR = 0.91; 95%CI; 0.88, 0.94), women from male-headed households (aRRR = 0.95; 95%CI; 0.92, 0.99), those who use contraceptives (aRRR = 0.81; 95%CI; 0.79, 0.84), women who have a higher number of living children, parous women, women from eastern and southern Africa, and women from wealthy households had relatively less desire for more children. While, having a higher number of ideal children, having decision-making autonomy, and being from a rural residence were associated with a relatively higher desire for more children. Regarding factors associated with undecided fertility desire, older women, higher husband educational status, working women, a higher number of living children, higher parity, having exposure to media, women from wealthy households, women from rural residence, women from eastern and southern Africa had relatively less likelihood of undecided fertility desire. While women who had decision-making autonomy and a higher number of ideal children had relatively higher undecided future fertility desires (Table 4).

Regarding the random effect results, in the null model, there were substantial variations in fertility decisions across clusters (variance = 0.06, 95% CI; 0.04, 0.08). The null model also showed that around 2% of the total variance in fertility decisions was attributed to between-cluster variation (ICC = 0.018). Besides, the highest PCV in model 3 revealed that about 43% of the variability in fertility decisions was explained by both individual and community-level characteristics. Looking at model fitness, model 3 was the best-fitted model since it had the lowest deviance (Table 5).

Discussion

This study aimed to assess fertility decisions and their associated factors in Sub-Saharan Africa. The study at hand revealed that 64.35% and 5.4% of the study participants had a desire for more children and did not decide about their fertility, respectively. This desire for more children is comparable with studies conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa and Uganda [16, 23]. However, it was higher than study findings from elsewhere [7, 24, 25]. Discrepancies in research scope and setting, the sample population, and the time these studies were conducted are all plausible explanations for the differences in study findings. The higher proportion of desire for more children found in this study could be explained by the priority placed on having more children in most regions of SSA.

In the multilevel multinomial regression, both individual and community-level factors were associated with both desires for more children and undecided fertility desires.

Women in the young age group had a relatively higher desire for more children, however, as the women get older the relative desire for more children and undecided fertility desire were lower as compared to women in the age group 15–19. This finding is comparable with different studies conducted elsewhere [16, 26,27,28,29,30]. This could be because younger women did not achieve their reproductive goals and are more inclined to want more children later in life.

In this study, women with primary, secondary, and higher education had less desire to have more children as compared to those women with no formal education. This finding is in line with many previous works of literature in different settings [16, 31,32,33]. The possible explanation is that for highly educated women, it is sometimes problematic to combine many children and life goals such as occupying a certain managerial position. Furthermore, less educated women are usually unemployed and spend the majority of their time as housewives caring for their children, which allows them to continue to have additional children. It's also possible that the majority of women in this study live in rural areas where children are valued as assets.

We observed from this study that women from wealthy households and working women were less likely to desire more children. This corroborates with studies conducted in SSA [16] and Iran [34]. This may be due to the perception of women from higher socioeconomic levels that having more children is a burden that strains resources such as time. Women with poor socioeconomic status, on the other hand, may prefer to have more children and they perceive it as a logical economic decision because each child is seen as an additional asset for stability when they become old.

Consistent with a study finding from SSA [16], women who could not make decisions on their own were more likely to desire additional children. This indicated that making life choices without interference gives people the opportunity to practice or apply their choices. The study also revealed that women with a higher number of living children were less likely to desire more children. This is in line with a study finding from SSA [16, 30]. The possible explanation is that women with a larger number of living children may be satisfied with their current family size or have met their reproductive goals. We also noted that a higher ideal number of children was associated with a higher likelihood of desiring more children. The study conducted in sub-Saharan Africa also reported that having at least six ideal numbers of children is linked to a higher likelihood to desire more children [16].

Consistent with other study findings [16, 27, 35], contraceptive use was associated with the desire for more children. Contraception users were found to have a decreased desire to have more children than their counterparts. The study also showed that women who were from rural areas were more likely to desire more children, compared to women in urban areas. This is consistent with what is reported in Nigeria and Iran [30, 32]. This could be because women in rural areas are engaged in farming and see children as a source of labor for their agricultural activities. Moreover, consistent with different study findings [16], this study revealed that there is a regional variation in the desire for more children. This may be due to the cultural and socioeconomic differences between regions of SSA.

This study has both strengths and limitations. A major strength of this study is the use of nationally representative datasets from SSA nations and the application of relevant statistical techniques (multilevel multinomial regression analysis). Despite these advantages, there may be a possibility of social desirability bias. In addition, important confounding factors such as HIV status and other sociocultural factors that may be associated with reproductive desire are not considered. Furthermore, because no previous research on undecided fertility desire has been conducted, we are unable to discuss factors associated with undecided fertility desire in detail.

Conclusion

Around two-thirds of women desire more children and a small proportion of women had undecided fertility desires. Both individual and community-level factors were associated with desires for more children and undecided fertility desires. Among individual-level factors, older age, having primary, secondary, and higher education, working, having decision-making autonomy, a higher number of living children, higher parity, being using contraceptives, a lower ideal number of children, and being from wealthy households were associated with a lower relative risk for the desire for more children and undecided fertility desire, respectively. Besides, being from female-headed households was associated with a relatively higher likelihood of desire for more children while women whose husbands had primary and above education and had been exposed to media had a lower likelihood of undecided fertility desire. Among community-level variables, rural residence was positively associated with a desire for more children and negatively associated with undecided fertility desire. In addition, being from the eastern and southern regions of Africa was associated with a lower risk for desiring more children and undecided fertility desire, respectively. As a result, organizations such as the United Nations Population Fund and Population Media Center should emphasize the discovered determinants while intervening in rapid population growth due to unlimited fertility desire. Besides, those aiming at reducing the fertility rate of women such as the sustainable development goal should focus on drivers of desire for more children, that is both individual and community-level factors.

Availability of data and materials

All result-based data are within the manuscript and anyone can access the data set from the measure DHS program using https://dhsprogram.com.

Abbreviations

- aRRR:

-

Adjusted relative risk

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DHS:

-

Demographic and health surveys,

- ICC:

-

Intraclass correlation coefficient

- PCV:

-

Proportional change in variance

- SDG:

-

Sustainable development goal

- SSA:

-

Sub-Saharan Africa

References

UN, United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs PD. World Population Prospects: The 2019 Revision | Multimedia Library - United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, vol. 9; 2019. p. 1–13. https://population.un.org/wpp/Download.

Aziz Ali SAA, Aziz Ali S, Khuwaja NS. Determinants of unintended pregnancy among women of reproductive age in developing countries: a narrative review. J Midwifery Reprod Health. 2016;4(1):513–21.

Population Reference Bureau. World Population Data Sheet. 2019.

Guengant J-P, May JF. Sub-Saharan Africa within global demography. Etudes. 2011;415(10):305–16.

Crist E, Mora C, Engelman R. The interaction of human population, food production, and biodiversity protection. Science. 2017;356(6335):260–4.

Das GM. Population, poverty, and climate change. World Bank Res Obs. 2014;29(1):83–108.

Gutin SA, Namusoke F, Shade SB, Mirembe F. Fertility desires and intentions among HIV-positive women during the post-natal period in Uganda. Afr J Reprod Health. 2014;18(3):67–77.

United Nations, D.o.E. and P. D. Social Affairs, World Population Prospects 2019: Highlights. 2019.

Amalba A, Mogre V, Appiah MN, Mumuni WA. Awareness, use and associated factors of emergency contraceptive pills among women of reproductive age (15–49 years) in tamale. Ghana BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14(1):1–6.

World Bank. Contraceptive prevalence, any methods (% of women ages 15–49). avialiable at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.CONU.ZS. Accessed 13 Nov 2021.

Westoff CF. Desired number of children: 2000–2008. DHS Comparative Reports No. 25. Calverton: ICF Macro; 2010. http://dhsprogram.com/pubs/ pdf/CR25/CR25.pdf.

Adhikari R. Demographic, socio-economic, and cultural factors affecting fertility differentials in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010;10(1):1–11.

Rai P, Paudel IS, Ghimire A, Pokharel PK, Rijal R, Niraula SR. Effect of gender preference on fertility: cross-sectional study among women of Tharu community from rural area of eastern region of Nepal. Reprod Health. 2014;11(1):1–6.

Adibi Sedeh M, Arjmand Siahpoush E, Darvishzadeh Z. The investigation of fertility increase and effective factors on it among the kord clan in Andimeshk. J Iranian Soc Develop Stud. 2012;4(1):81–98.

Black DA, Kolesnikova N, Sanders SG, Taylor LJ. Are children “normal”? Rev Econ Stat. 2013;95(1):21–33.

Ahinkorah BO, Seidu A-A, Armah-Ansah EK, Budu E, Ameyaw EK, Agbaglo E, et al. Drivers of desire for more children among childbearing women in sub-Saharan Africa: implications for fertility control. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020;20(1):1–11.

Feyisetan B, Casterline JB. Fertility preferences and contraceptive change in developing countries. Int Family Plan Perspect. 2000. https://doi.org/10.2307/2648298.

Srivastava U, Singh A, Verma P, Singh KK. The role of change in fertility desire on change in family planning use: a longitudinal investigation in urban Uttar Pradesh, India. Gates Open Research. 2019;3:1439.

United Nations Statistics Division, Sustainable Development Goals indicators; Available from https:// unstats.un.org/sdgs/metadata/.

Bongaarts J, O’Neill BC. Global warming policy: is population left out in the cold? Science. 2018;361(6403):650–2.

Aliaga A, Ruilin R, editors. Cluster optimal sample size for demographic and health surveys. 7th International Conference on Teaching Statistics–ICOTS; 2006.

The DHS Program. Sampling and Weighting with DHS Data. Sep 2015. Avialable at https://blog.dhsprogram.com/sampling-weighting-at-dhs/

Matovu JK, Makumbi F, Wanyenze RK, Serwadda D. Determinants of fertility desire among married or cohabiting individuals in Rakai, Uganda: a cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):1–11.

Kawale P, Mindry D, Stramotas S, Chilikoh P, Phoya A, Henry K, et al. Factors associated with desire for children among HIV-infected women and men: a quantitative and qualitative analysis from Malawi and implications for the delivery of safer conception counseling. AIDS Care. 2014;26(6):769–76.

Negash S, Yusuf L, Tefera M. Fertility desires predictors among people living with HIV/AIDS at art care centers of two teaching hospitals in Addis Ababa. Ethiop Med J. 2013;51(1):1–11.

Eklund L. Preference or aversion? Exploring fertility desires among China’s young urban elite. Intersections: Gender and Sexuality in Asia and the Pacific. 2016;39:1–16.

Haile F, Isahak N, Dessie A. Fertility desire and associated factors among people living with HIV on ART. Harari Regional State, Eastern Ethiopia J Trop Dis. 2014;2(3).

Kariman N, Simbar M, Ahmadi F, Vedadhir AA. Socioeconomic and emotional predictors of decision making for timing motherhood among Iranian women in 2013. Iranian Red Crescent Med J. 2014. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.13629.

Kodzi IA, Johnson DR, Casterline JB. Examining the predictive value of fertility preferences among Ghanaian women. Demogr Res. 2010;22:965.

Tavousi M, Haerimehrizi A, Sadighi J, Motlagh ME, Eslami M, Naghizadeh F, et al. Fertility desire among Iranians: a nationwide study. 2017.

Jiang L, Hardee K. Women’s education, family planning, or both? Application of multistate demographic projections in India. Int J Population Res. 2014. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/940509.

Akpa OM, Ikpotokin O. Modeling the determinants of fertility among women of childbearing age in Nigeria: analysis using generalized linear modeling approach. Int J Humanit Soc Sci. 2012;2(18):106–7.

Testa MR. On the positive correlation between education and fertility intentions in Europe: individual-and country-level evidence. Adv Life Course Res. 2014;21:28–42.

Araban M, Karimy M, Armoon B, Zamani-Alavijeh F. Factors related to childbearing intentions among women: a cross-sectional study in health centers, Saveh Iran. J Egyptian Public Health Assoc. 2020;95(1):1–8.

Aylie NS, Dadi LS, Alemayehu E, Mekonn MA. Determinants of fertility desire among women living with HIV in the childbearing age attending antiretroviral therapy clinic at jimma university medical center, Southwest Ethiopia: a facility-based case-control study. Int J Reprod Med. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/65045672020.

Acknowledgements

Our heartfelt thanks go to the MEASURE DHS Program, which permitted us to use DHS data.

Funding

No funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ABT developed the concept, reviewed literature, carried out the statistical analysis, interpret and discuss the results, and drafted the manuscript. MGW and GAT reviewed literature, were involved in analysis, interpreting, and discussing results, and reviewed the drafted manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was conducted under the Declaration of Helsinki and since we used publicly accessible data, ethical approval was not needed. However, we have accessed the data set from the DHS website (https://dhsprogram.com) by registering and online requesting. Besides, no personal identifiers were found in the data set.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Teshale, A.B., Worku, M.G. & Tesema, G.A. Fertility decision and its associated factors in Sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel multinomial logistic regression analysis. BMC Women's Health 22, 337 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01920-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01920-w