Abstract

Background

The government of Ethiopia has been implementing compassionate, respectful, and caring strategies to increase institutional delivery and decrease maternal mortality in recent years. There is limited evidence on respectful delivery care and associated factors in low-income countries like Ethiopia. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the proportion of respectful delivery care and associated factors among mothers delivered in the health facilities of Dessie city, Northeast Ethiopia.

Methods

A health facility-based cross-sectional study was conducted among a total of 390 mothers from April 16 to May 30, 2018. A pretested structured interviewer-administered questionnaire was used to collect the data. The data were entered into Epidata and analyzed using Stata/SE 14. Binary logistic regression analysis was used to identify associated factors. Variables having P-value less than 0.2 in the bivariable regression were selected as a candidate for multi-variable regression. Adjusted odds ratio (AOR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated to measure the strength and direction of the association respectively.

Results

The proportion of respectful delivery care among mothers delivered in public health facilities of Dessie city was 43.4%, 95% CI (39.1%, 47.6%). It was found to be 34.9% in hospital and 74.1 in health center. Respectful delivery care was associated with day time delivery [AOR = 2.23, 95% CI (1.30, 3.82)], any maternal and/or fetal complications [AOR = 0.50, 95% CI (0.27, 0.94)], gave birth in health center [AOR = 3.22, 95% CI (1.61, 6.46)] and educated mothers [AOR = 2.87, 95% CI (1.18, 7.01)].

Conclusions

The proportion of respectful delivery care in the study area was low as compared to the government emphasis and other works of literature. This study indicated that any maternal and/or newborn complications, daytime delivery, giving birth in a health center, and maternal education were associated with respectful delivery care. Women empowerment through education could be a recalled intervention for respectful care.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Respectful maternal care is an approach that focuses on the individual, based on principles of ethics and respect for human rights [1]. Since respect and dignity have been identified as essential components of good quality of care [2, 3], the World Health Organization (WHO) has launched a statement on prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during childbirth [4, 5]. Even every woman has the right to get respectful care, many women in the world have experienced the situation of abuse during childbirth [6,7,8]. A study conducted in India indicated that only 45.3% of women were treated respectfully [9]. It becomes worse in Nigeria as only 2% were respected and 86.1% in Malawi were treated respectfully [10, 11] while it was ranged between 22 and 78.9% in Ethiopia [12, 13].

Respectful delivery care is one of the opportunities for increasing maternal health service utilization [9, 14,15,16,17,18,19]. Sixty-one percent of mistreated women wanted to deliver by someone else and only 27% intend to deliver in a facility next time [20, 21]. Seventy-nine percent of maternal deaths were resulted due to substandard care [22]. Poor quality of delivery care constitutes a 10% case fatality rate [14] and 2.9 million neonatal deaths per year could be prevented through timely and skilled delivery care [23, 24]. Any form of disrespect from maternal health care providers (MHCPs) resulted in distress and fear among mothers and led to an absence of trust in providers [25].

Numerous studies indicated that maternal respect during childbirth could be influenced by maternal characteristics (age, educational status, occupation, residence) [1, 26, 27], health care provider’s characteristics (type of profession, estimated work hour per day, sex of profession) [25, 28,29,30,31,32] and health facilities characteristics (type of facility) [1, 13, 14, 25]. The government of Ethiopia also adopts SDG and Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP II). These strategies emphasize maternal health to decrease MMR (below 199 and 267/100,000 live birth respectively) and increase institutional delivery [33, 34]. In spite of the fact that 412/100,000 women were died due to pregnancy-related causes, only 62% of pregnant women had ANC visits at least one time and only 26% of them gave birth in health facilities [35]. Although there are some studies on respectful delivery care, those studies are limited and not large enough for policy development. There was no similar study conducted in the study setting as problems are non-stationary and Ethiopia is a multi-cultural country and local or context-specific evidence is needed for planning. In addition, the studies are more qualitative and less emphasized on the factors, especially health facility and health care provider factors (type of health facility, sex of health care provider, the profession of health care provider, provider experience, estimated work hour per day). As a result, this study aimed to assess the proportion of respectful delivery care and associated factors among mothers who delivered in the health facilities of Dessie city, Northeast Ethiopia.

Methods

Study setting, design, and population

A facility-based cross-sectional study design was conducted in the health facilities of Dessie city, Northeast Ethiopia. Dessie is the capital city of South Wollo Zone including its town administration, which is located 401 km to the North of Addis Ababa. The study was conducted from April 16 to May 30, 2018. Women who gave birth in the health facilities of Dessie city during the data collection time were included in the study and mothers who took general anesthesia during cesarean section delivery were excluded since they didn’t know in what way the provider treated them until full recovery that may lead to bias.

Sample size determination and sampling procedure

Sample size was determined by single population proportion formula by considering the following assumptions. Proportion of respectful delivery care in Ethiopia from previous study was 64% [13], 95% of confidence level and allowed margin of error 5%.

Adding 10% for non-response the final sample size was n = 390. The sample size was also calculated based on the second objective for independent variables. By taking postpartum complication as an independent variable, percent of outcome in unexposed 69.3%, percent of outcome in exposed 78%, adjusted odds ratio 2, power 80%, confidence level 95%, and adding 10% non-response rate the sample size was 383. But, the sample size calculated using a single population proportion was greater than the one calculated for the factor so, the final sample size was (n = 390). The samples were initially proportionately allocated for each health facility based on their average number of delivery per month. Then, women were selected by systematic sampling procedure based on client flow and interviewed at the time of discharge (Fig. 1).

Operational definition

Respectful delivery care was recorded as a dichotomous (yes or no) using a checklist that includes thirteen items as a desirable action of health providers. If a woman answered ‘yes’ for all of the thirteen questions, she was respected, otherwise disrespected [26, 36,37,38,39].

Wealth index: This is a composite variable that was calculated for urban and rural separately and it includes the following classification [35].

-

Lowest: Includes women whose wealth was less than or equal to 20 percentile.

-

Low: Includes women whose wealth was ranged 21 to 40 percentile.

-

Medium: Includes women whose wealth was ranged 41 to 60 percentile.

-

High: Includes women whose wealth was ranged 61 to 80 percentile.

-

Highest: Includes women whose wealth was ranged 81 to 100 percentile.

Maternal complication: When a woman developed one or more of the following; post-partum hemorrhage, antepartum hemorrhage, chorioamnionites, preeclampsia, eclampsia, severe oligohydramnios, severe polyhydramnios, 3rd, and 4th-degree tear and abnormal adherent placenta/retained placenta, and any other complications [40]. Neonatal complication: If a neonate developed one or more of the following; mal-presentation, cord compression, distress, and any other complication to the newborn [40].

Data collection tools, procedures, quality control, and analysis

The questionnaires were developed by reviewing the result of different studies and the national Compassionate, Respectful and Caring (CRC) guidelines [12, 13, 41]. The women in the labour ward were asked for the interview at the time of discharge for their valuable information and the data was filled in the questionnaire. Some of the questionnaires were also filled by observing the delivery card of mothers. Two BSc public health supervisors and six BSc nurses were employed as data collectors and they were doing in another health facility. The questionnaire was developed in English language and translated to Amharic again back-translated to English to check its consistency. Supervisors and data collectors were trained on the objective of the study, how to approach participants, and take informed consent. The tool was pre-tested on 5% samples in Kombolcha health center coming for the same service before entering the actual data collection and necessary modification was done according to the result of the pretest. The checklists used for measuring the outcome variable was checked for their reliability (Cronbach’s alpha value = 0.717) and the data were also continuously checked by supervisors and principal investigator.

The data were coded and entered into Epi-Data version 3.1 and exported to Stata/SE 14 for analysis. The result was presented using texts, frequency, percentage, and graph. First bi-variable binary logistic regression analysis was done and those variables with a p-value less than 0.2 were entered into multiple logistic regression to control confounding. Multi-colinearity between independent variables was checked using variance inflation factor as well as standard error and there is no multi-colinearity. Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to check for model fitness and it was not significant (P-value = 0.791). In the final model, those variables with a p-value less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Odds ratio (OR) along with 95% confidence interval (CI) was estimated to measure the strength and direction of the association respectively.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of respondents

Three hundred ninety delivered women were participated, making the response rate of 99.7%. More than half (63.2%) were aged between 20 and 29 years. One hundred eighty (46.2%) were educated to secondary and above whereas 94 (24.1%) were not formally educated. About two-thirds of (68.9%) mothers were Muslims and 13 (3.3%) were protestants. In terms of ethnicity and occupation, 366 (94.1%) were Amhara and 262 (67.4%) were housewives (Table 1).

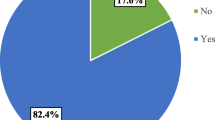

Proportion of respectful delivery care

The overall proportion of respectful delivery care among mothers who delivered in health facilities of Dessie city was 43.4% [95% CI (39.1, 47.6)] (Fig. 2). It was found to be 34.9% in hospitals and 74.1 in a health centers.

Factors associated with respectful delivery care

The multivariable analysis result showed that the educational status of mothers, delivery time, and any fetal and/or maternal complications was found to have a statistical association with respectful delivery care. The odds of obtaining respectful delivery care for mothers educated up to grade 9–12 were almost 3 times higher as compared to mothers who couldn’t read and write [AOR = 2.87, 95% CI (1.18, 7.01)]. Those mothers who gave birth during day time were 2 times greater in receiving respectful delivery care than mothers who gave birth during night time [AOR = 2.23, 95% CI (1.30, 3.82)]. The odds of getting respectful delivery care for mothers who gave birth in a health center were 3.2 times more likely than those mothers who gave birth in a hospital [AOR = 3.22, 95% CI (1.61, 6.46)]. The odds of getting respectful delivery care were 50% less likely for mothers who faced any complication to her and/or her neonate as compared to mothers who didn’t face it [AOR = 0.50, 95% CI (0.27, 0.94)] (Table 2).

Discussion

In this study, the proportion of respectful delivery care was 43.4% and variables like time of delivery, maternal education, and occurrence of any maternal and/or fetal complication were significantly associated with respectful delivery care. The finding of this study is in line with a study conducted in Malawi (41.8%) [11]. But, it is lower than the previous study conducted in four regions of Ethiopia (64%) [41]. It is also lower than previous studies conducted in Kenya (80%) [42], Tanzania (85%) [43], and Nigeria (98%) [10]. The possible reason for this discrepancy may be due to time variation and differences in socio-cultural contexts of the study settings. Moreover, those previous studies were either observational or repeated client exit interviews whereas this study was only client exit interviews during immediate postpartum.

But, it is higher than another study conducted in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (22%) [12], and India (22.7%) [36]. The discrepancy may be due to that the previous studies were used twenty-three items checklist to measure respectful delivery care but, this study used thirteen items. This implies that significant numbers of women were facing disrespect and abuse delivery care in the study setting. So, home delivery will persist high as far as respectful delivery care is not present in the groud and maternal and neonatal mortality will not be decreased as what is expected.

The higher educational status of mothers was positively associated with respectful delivery care. In contrast to this finding, studies conducted in Tanzania stated that educated women were more likely to experience disrespect [26]. The possible reason for this variation may be due to variation in the context like socio-demographic and cultural factors may attribute for the difference in the above two research’s. The possible justification for this association might be due to the reason that those educated mothers might understand their rights better than non-educated (counterparts) to follow physicians' orders.

This study revealed a significant negative relationship between complications and mothers’ respect. This finding is in line with studies conducted in Ethiopia [12], Tanzania [26], and India [36]. The possible reason for this association might be that complicated labour requires frequent and careful follow-up and monitoring that makes the provider more tiresome and keeping all her rights may endanger her life, especially during emergencies.

The finding also demonstrated that daytime childbirth was associated with respectful delivery care. The result of this study is similar to the previous study conducted in Ethiopia [13]. It is also similar to a study conducted in Kenya [44]. This might be due to that health providers during the nighttime may be disturbed and they may not act as normal because they awake from sleep. Additionally, the nighttime health workers might be overburdened by high numbers of client flow because of an incongruent number of providers assigned.

Type of health facility is also another significantly associated variable to respectful delivery care. Those mothers who gave birth in health centers were three times more likely to be respected than those mothers who gave birth in hospitals. The finding of the study is similar to the studies conducted in Ethiopia [13, 41]. It is also similar to a study conducted in Malawi [11]. The possible reason for this association may be due to the fact that high client flow in hospitals may make the providers become very busy and highly burdened [45, 46].

Despite this study addressed respectful delivery care quantitativelty, it is not without limitations. As the outcome was measured indirectly from mothers, this may make the study prone to recall bias since women may not be perfect in remembering or told in what way they were treated. Lastly, the study was only on governmental health facilities that may not represent the experiences of private health facilities delivery care.

Conclusions

Even though CRC in Ethiopia is a current governmental agenda, the proportion of respectful delivery care is still lower as compared to the WHO recommendation. The study indicated that any maternal/newborn complication, time of delivery, and maternal education were associated with respectful delivery care. Respectful delivery care can be improved by giving especial emphasis to nighttime delivery, facing any complication to her and/or her child, giving birth in a hospital, and on uneducated mothers. The findings suggested that continue the pre-started CRC strategies, especially nighttime health workers to improve women’s experience of respectful delivery care. Women empowerment through education could also be the recalled intervention for respectful care. All delivery attendants should serve clients respectfully irrespective of mothers' educational status, maternal/newborn complications, and delivery time.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during this study are attached with the manuscript (see Additional file 1).

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- CRC:

-

Compassionate respectful and caring

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- MHCPs:

-

Maternal Health Care Provider

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Reis V, Deller B, Catherine Carr C, Smith J. Respectful maternity care. Washington, DC: USAID; 2012.

Tunçalp Ӧ, Were W, MacLennan C, Oladapo O, Gülmezoglu A, Bahl R, et al. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—the WHO vision. BJOG. 2015;122(8):1045.

Mathai M, Say L, Kristensen F, Temmerman M, Bustreoc F. Quality of care for pregnant women and newborns—the WHO vision.

World Health Organization. World health statistics 2016: monitoring health for the SDGs sustainable development goals: World Health Organization; 2016.

World Health Organization. The prevention and elimination of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth: WHO statement. World Health Organization; 2014.

Miller S, Abalos E, Chamillard M, Ciapponi A, Colaci D, Comandé D, et al. Beyond too little, too late and too much, too soon: a pathway towards evidence-based, respectful maternity care worldwide. The Lancet. 2016;388(10056):2176–92.

Bohren MA, Vogel JP, Hunter EC, Lutsiv O, Makh SK, Souza JP, et al. The mistreatment of women during childbirth in health facilities globally: a mixed-methods systematic review. PLoS Med. 2015;12(6): e1001847.

Windau-Melmer T. A guide for advocating for respectful maternity care. Washington, DC: USAID; 2013.

Sudhinaraset M, Treleaven E, Melo J, Singh K, Diamond-Smith N. Women’s status and experiences of mistreatment during childbirth in Uttar Pradesh: a mixed methods study using cultural health capital theory. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2016;16(1):1–12.

Okafor II, Ugwu EO, Obi SN. Disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in a low-income country. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2015;128(2):110–3.

Sethi R, Gupta S, Oseni L, Mtimuni A, Rashidi T, Kachale F. The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based maternity care in Malawi: evidence from direct observations of labor and delivery. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):111.

Asefa A, Bekele D. Status of respectful and non-abusive care during facility-based childbirth in a hospital and health centers in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):33.

Banks KP, Karim AM, Ratcliffe HL, Betemariam W, Langer A. Jeopardizing quality at the frontline of healthcare: prevalence and risk factors for disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in Ethiopia. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(3):317–27.

Nyamtema AS, de Jong AB, Urassa DP, van Roosmalen J. Using audit to enhance quality of maternity care in resource limited countries: lessons learnt from rural Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2011;11(1):94.

Molla M, Muleta M, Betemariam W, Fesseha N, Karim A. Disrespect and abuse during pregnancy, labour and childbirth: a qualitative study from four primary healthcare centres of Amhara and Southern Nations Nationalities and People’s Regional States, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2017;31(3):129–37.

Oates J, Weston WW, Jordan J. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804.

Hodnett ED. Pain and women’s satisfaction with the experience of childbirth: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186(5):S160–72.

Waldenström U, Hildingsson I, Rubertsson C, Rådestad I. A negative birth experience: prevalence and risk factors in a national sample. Birth. 2004;31(1):17–27.

Green JM, Coupland VA, Kitzinger JV. Expectations, experiences, and psychological outcomes of childbirth: a prospective study of 825 women. Birth. 1990;17(1):15–24.

Vogel JP, Bohren MA, Tunçalp Ö, Oladapo OT, Adanu RM, Baldé MD, et al. How women are treated during facility-based childbirth: development and validation of measurement tools in four countries–phase 1 formative research study protocol. Reprod Health. 2015;12(1):60.

Peca E, Sandberg J. Modeling the relationship between women’s perceptions and future intention to use institutional maternity care in the Western Highlands of Guatemala. Reprod Health. 2018;15(1):9.

Wagaarachchi PT, Fernando L. Trends in maternal mortality and assessment of substandard care in a tertiary care hospital. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2002;101(1):36–40.

Mason E, McDougall L, Lawn JE, Gupta A, Claeson M, Pillay Y, et al. From evidence to action to deliver a healthy start for the next generation. The Lancet. 2014;384(9941):455–67.

Fink G, Ross R, Hill K. Institutional deliveries weakly associated with improved neonatal survival in developing countries: evidence from 192 Demographic and Health Surveys. Int J Epidemiol. 2015;44(6):1879–88.

Mannava P, Durrant K, Fisher J, Chersich M, Luchters S. Attitudes and behaviours of maternal health care providers in interactions with clients: a systematic review. Glob Health. 2015;11(1):36.

Kruk ME, Kujawski S, Mbaruku G, Ramsey K, Moyo W, Freedman LP. Disrespectful and abusive treatment during facility delivery in Tanzania: a facility and community survey. Health Policy Plan. 2018;33(1):e26–33.

Ratcliffe H. Creating an evidence base for the promotion of respectful maternity care. Boston: Harvard School of Public Health, Harvard University, Department of Global Health and Population. 2013.

Balde MD, Bangoura A, Sall O, Balde H, Niakate AS, Vogel JP, et al. A qualitative study of women’s and health providers’ attitudes and acceptability of mistreatment during childbirth in health facilities in Guinea. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):1–13.

Koblinsky M, Matthews Z, Hussein J, Mavalankar D, Mridha MK, Anwar I, et al. Going to scale with professional skilled care. The Lancet. 2006;368(9544):1377–86.

Liu T-C, Lin H-C, Chen C-S, Lee H-C. Obstetrician gender and the likelihood of performing a maternal request for a cesarean delivery. Eur J Obst Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2008;136(1):46–52.

Kirimlioglu N, Sayligil Ö. Do patients prefer male or female physicians/counselors during family planning, pregnancy and birth process? A sample from Turkey. Osmangazi Tıp Dergisi. 2020;38(1):36–44.

Jewkes R, Abrahams N, Mvo Z. Why do nurses abuse patients? Reflections from South African obstetric services. Soc Sci Med. 2015;47(11):1781–95.

United Natin (UN). Sutainable Developmental Goal. New York: United nation;2016.

The Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia Growth and Transformation Plan (GTP) Draft Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED). 2016.

Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopian and ICF International] Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia and Rockville, Maryland, USA: Central Statistical Agency International;2016.

Dey A, Shakya HB, Chandurkar D, Kumar S, Das AK, Anthony J, et al. Discordance in self-report and observation data on mistreatment of women by providers during childbirth in Uttar Pradesh, India. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):149.

Bowser D, Hill K. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth. Boston: USAID-TRAction Project, Harvard School of Public Health; 2010.

Browser D, Hill K. Exploring evidence for disrespect and abuse in facility-based childbirth: report of a landscape analysis-USAID. 2015.

Kujawski SA, Freedman LP, Ramsey K, Mbaruku G, Mbuyita S, Moyo W, et al. Community and health system intervention to reduce disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Tanga region, Tanzania: a comparative before-and-after study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(7): e1002341.

Negussie S. Obstetrics and gynecology lecture note foe health science students: 2014.

Sheferaw ED, Bazant E, Gibson H, Fenta HB, Ayalew F, Belay TB, et al. Respectful maternity care in Ethiopian public health facilities. Reprod Health. 2017;14(1):60.

Abuya T, Warren CE, Miller N, Njuki R, Ndwiga C, Maranga A, et al. Exploring the prevalence of disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(4): e0123606.

Sando D, Ratcliffe H, McDonald K, Spiegelman D, Lyatuu G, Mwanyika-Sando M, et al. The prevalence of disrespect and abuse during facility-based childbirth in urban Tanzania. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2016;16(1):236.

Abuya T, Ndwiga C, Ritter J, Kanya L, Bellows B, Binkin N, et al. The effect of a multi-component intervention on disrespect and abuse during childbirth in Kenya. BMC Pregnancy Childb. 2015;15(1):224.

Biksegn A, Kenfe T, Matiwos S, Eshetu G. Burnout status at work among health care professionals in atertiary hospital. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2016;26(2):101–8.

Salyers MP, Bonfils KA, Luther L, Firmin RL, White DA, Adams EL, et al. The relationship between professional burnout and quality and safety in healthcare: a meta-analysis. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(4):475–82.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Wollo University for creating different opportunities to conduct the research.

Funding

There is no specific funding for this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MY: Collected and analyzed the data, BK and MY: analysed and wrote the result, YD: drafted the manuscript and DN and TY: revised and edited the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethical review committee of Wollo University, College of Medicine and Health Sciences with the ethical approval number of CMHS/2850/15/10. Besides, the official letter of cooperation was submitted to health facilities, and written informed consent was obtained from each respondent before enrollment. Each participant was informed about the aim of the study and all data obtained from them would be kept confidential by assigning codes instead of using names and other personal identifiers. In this study, all of the methods were carried out in accordance with the relevant institutional guidelines and regulations. Similarly, all methods were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1:

The dataset used or analysed in the current study.

Additional file 2:

The English version questionaries.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Yalew, M., Nigatu, D., Yasin, T. et al. Respectful delivery care and associated factors among mothers delivered in public health facilities of Dessie city, Northeast Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. BMC Women's Health 22, 127 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01713-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01713-1