Abstract

Background

The condition of recurrent, crampy, lower abdominal pain during menses is defined as dysmenorrhea. The study aims to assess the factors affecting the prevalence of primary and secondary dysmenorrhea among Saudi women from the reproductive age group.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey-based study recruited 1199 participants through a systematic random sampling technique. The study was carried out among the reproductive age group in Saudi women (total number of 1199) who are more than 18-year-old and less than 45-year-old in Riyadh, King Dom of Saudi Arabia, using an electronic questionnaire.

Results

The observed dysmenorrhea in the study; 1107 (92.3%) women had non-pathological dysmenorrhea (primary) while 92 (7.7%) women had pathological dysmenorrhea (secondary) respectively.

Conclusion

In the present study, the prevalence of dysmenorrhea was high among the recruited Saudi women. The study suggests the inclusion of health education programs for students at the school and university level to deal with problems associated with dysmenorrhea that limit their interference with the student’s life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The crampy, recurrent pain in the lower abdomen during menses is defined as dysmenorrhea [1]. Dysmenorrhea is divided into two broad categories, i.e., primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. The presence of crampy, recurrent pain in the lower abdomen during menses in the absence of demonstrable disease is primary dysmenorrhea. Adolescents and young women are more likely to be diagnosed with primary dysmenorrhea, an exclusionary diagnosis. Women suffer from pain related symptoms in secondary dysmenorrhea, with a disorder accounting for symptoms like endometriosis, uterine fibroids, or adenomyosis. The significant clinical features experienced by women suffering from secondary dysmenorrhea include pain during intercourse, resistance to effective treatment, and enlarged uterus [2].

Prostaglandins play a significant role in inducing uterine contractions released from endometrial sloughing at the start of menses [3, 4]. The contractions occur at a frequency of > 4–5 per minute (high frequency) and are incoordinate and nonrhythmic. These contractions result in increased intrauterine pressures, which may even exceed 400 mmHg (ranging between 150 and 180 mmHg) [5]. There is the development of uterine ischemia and accumulation of anaerobic metabolites as uterine pressure exceeds the arterial pressure stimulating type C pain neurons that cause dysmenorrhea. The pain perception can also be determined through stretch receptors’ activation.

Dysmenorrhea is a common problem, and it is experienced by 50–90% of women in their reproductive years worldwide, describing having painful menstruation [6]. Young women with primary dysmenorrhea make the majority group of these women. Primary dysmenorrhea tends to decrease with advancing age [7]. However, secondary dysmenorrhea develops later in life [7]. The dysmenorrhea prevalence among Saudi young women ranges from 60.9 to 89.7% [8,9,10,11,12,13]. These studies were performed in different cities in Saudi Arabia [8,9,10,11,12,13]. Dysmenorrhea-associated risk factors include younger age (adolescents in particular), smoking, and stress [14, 15]. Risk reduction is accompanied by hormonal contraceptives, higher parity, and having the first childbirth at a younger age [16, 17]. The severity of dysmenorrhea ranges from mild to severe [1]. Patients with dysmenorrhea often report depressed mood, anger, eating more than usual, nausea, dizziness, headache, fatigue, diarrhoea, or constipation associated with dysmenorrhea [12].

To attain targeted intervention and timely prevalence, it is significant to understand the disease burden among the population. In a similar context, the present study aims to determine factors affecting dysmenorrhea prevalence (primary and secondary) among Saudi women from the reproductive age group. The secondary objectives of the study are as follows;

-

To determine the relationship between dysmenorrhea and intake of dairy products.

-

To determine the relationship between dysmenorrhea and exercise

-

To evaluate the effects of dysmenorrhea on the quality of life

Methods

Study design and sampling

A cross-sectional survey-based study was conducted, and the participants were recruited through a systematic random sampling technique. The study was carried out among 1199 Saudi women. Epi Info was used to calculate the sample size at a 95% confidence level.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the study was Saudi women aged between 18 and 45 years and visiting the private clinic to undergo gynaecological examination for dysmenorrhea problems in Riyadh, King Dom of Saudi Arabia.

Study tool

The self-administered online questionnaire was used as a study tool on Google Forms. This type of survey was easy to administer and could include many participants.

Data collection

The study took place between July and September 2020.

The questionnaire was translated into validated Arabic language and back-translated into English. The questionnaire contained many parts, including sociodemographic questions such as (age, marital status, weight, height), menses related information such as (age at menarche, duration of menstrual cycle in last 12 months, regularity of menstrual cycle, duration of the menstrual flow, number of used pads, type of dysmenorrhea) and any medical or psychological illness. Other questions included the severity of menstrual cramps and treatment, possible symptoms associated with dysmenorrhea, general assessment of dairy products intake, and the effects of dysmenorrhea on activities of daily living.

Data analysis

The data gathered from the survey were entered on a Microsoft excel sheet and then analysed using Statistical Package of Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Frequencies and percentages were used to represent categorical variables; while, means and standard deviations represented continuous variables. Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to determine the normality of the tested data. However, groups on normally distributed variables were compared through parametric tests; while, skewed data was represented through non-parametric tests. The significant association between variables was determined using the chi-square / Fisher’s exact test, considering that cell expected frequency is < 5. The mean significant differences between the patient's age and the dysmenorrhea group were determined using an independent sample t-test. The results were considered statistically significant with a P value < 0.05.

Results

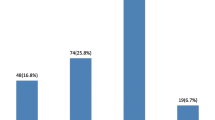

Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of 1199 women recruited in the study according to inclusion criteria. The mean age of women observed was 27.49 years, with a mean age of 12.76 years menarche. Concerning past medical history and psychological illness; 870 (72.6%) patients had not any past medical history, whereas 32 (2.7%) had irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), 35 (2.9%) had depression, and 81 (6.8%) had more than one medical or psychological illness (Table 2).

Table 3 shows a descriptive analysis of the menstrual cycle, regularity, and type of dysmenorrhea. According to it, 296 (24.7%) women had irregular menstrual cycles, and 103 (8.6%) had less than 21 days of the menstrual cycle, and 76 (6.3%) had irregular bleeding. The majority of them, 979 (81.7%), had the duration of the menstrual flow between 3 and 7 days. Around 92 (7.7%) women had pathological dysmenorrhea.

Table 4 depicts the analysis of the classification of dysmenorrhea pain, therapy and associated symptoms. Around 170 (14.2%) patients had severe pain. The majority of women, 1086 (88.4%), experienced pain in the lower abdomen, and the majority, 808 (67.4%), had pain for more than 3 days. For relieving pain, only 55 (4.6%) patients used NSAIDs only, and 747 (62.3%) patients used more than one analgesic or other alternative therapies used for relieving menstrual cramps. Considering the possible symptoms associated with dysmenorrhea, abdominal bloating is the most common single symptom that was observed among 35 (2.9%) women with dysmenorrhea, whereas, majority of them, 926 (77.2%), had more than one possible symptom associated with dysmenorrhea (Table 4).

Table 5 displays the distribution of dysmenorrhea limitation, academic performance, exercise and diet during menstruation. The different stress level was found during menstruation, where the majority, 614 (51.2%) of the women, usually had stress. Regarding limitation during menstruation, 161 (13.4%) women with dysmenorrhea reported to have a physical limitation, and 543 (45.3%) reported to have more than one limitation. Likewise, 122 (10.2%) reported dysmenorrhea affecting their concentration aspect of academic performance, and 462 (38.5%) patients had more than one factor affecting their academic performance. Around more than 512 (42.7%) women reported changes in sleeping routine. Furthermore, 268 (22.4%) performed more than one exercise during one exercise, and 260 (21.7%) reported exercise to reduce period pain. In connection with diet, 745 (62.1%) had all types of diet during the period.

Table 6 shows no statistically significant association among age, marital status, diabetes mellitus, IBS, Schizophrenia, and OCD with primary and secondary dysmenorrhea. However, most 775 (70%) women with age less than 30 years and the majority of the single women, 729 (65.9%), had primary dysmenorrhea. Around 55 (59.8%) women who had irregular menstrual cycles had significantly secondary dysmenorrhea (P < 0.001). Similarly, there was a significant association between the menstrual cycle duration in the last 12 months and primary and secondary dysmenorrhea (P < 0.001). Here, 11 (12.0%) women with less than 21 days cycle had secondary dysmenorrhea compared to 92 (8.3%) women with less than 21 days cycle with primary dysmenorrhea. Likewise, duration of the menstruation flow was significantly associated with the type of dysmenorrhea, were among women with more than 7 days cycle, 103 (9.3%) had primary and 19 (20.7%) had secondary dysmenorrhea (P = 0.002). Moreover, around 801 (72.4%) women with primary and 52 (56.5%) with secondary dysmenorrhea significantly used 3–5 pads per day (P = 0.004).

Table 7 shows a statistically significant association between the intensity of pain and primary and secondary dysmenorrhea (P = 0.006). Where majority of 539 (48.7%) women with primary dysmenorrhea had mild and 32 (34.8%) with secondary dysmenorrhea had moderate pain. Moreover, no significant association was demonstrated between the type of dysmenorrhea and pain localisation, duration and period of pain, and use of NSAIDs or paracetamols. Whereas, majority of the women with both types significantly did not use alternative therapies (hot pack) to relieve menstrual cramps (P = 0.013). There was no statistically significant association between dysmenorrhea and associated symptoms, limitation and affected academic performance (Table 8).

There was a statistically significant association between dysmenorrhea type and dietary habits, exercise and quality of life, as shown in Table 9. There was a statistically significant association between exercise during menstruation and primary and secondary dysmenorrhea (P = 0.001). It is shown that 1105 (99.8%) patients from primary and 90 (97.8%) secondary dysmenorrhea did not use bikes, respectively.

Discussion

The study aims to determine the factors affecting dysmenorrhea (primary and secondary) prevalence among Saudi women from the reproductive age group. Dysmenorrhea is an important symptom among many women of reproductive age. Dysmenorrhea has a significant impact on the health-related quality of life, work productivity, and health-care utilisation. The dysmenorrhea prevalence came out to be 95.3% in the present study. This prevalence was higher than that observed in the other studies in Saudi Arabia and worldwide [8,9,10,11,12,13]. The worldwide prevalence ranged from 50 to 90% [18,19,20,21]. The high majority observed in this study could be due to the different population age groups included in it or that the women who had the symptoms were more interested in taking part in it.

The study also determined the relationship between dysmenorrhea and intake of dairy products, which showed no significant association. A systematic review conducted by Zahra et al. [22] found that fruits, vegetables, milk, fish and dairy products had positive associations with decreased menstrual pain in primary dysmenorrhea. However, the majority of the participants did not have fruits, vegetables, and dairy products as part of their primary diet, which could be why there was a high prevalence of dysmenorrhea in the studied population.

Also, this study had the objective to elucidate the possible relationship between exercise and dysmenorrhea and to evaluate the impact of dysmenorrhea on the quality of life. Varied researches previously have shown dysmenorrhea to be impacted by multiple factors, of these were physical and daily activities, emotional health, social activities, family and friends’ relationships, in addition to the academic performance regarding concentration, attendance, class participation, and study time [23, 24]. In this study, the impact and association between dysmenorrhea and associated symptoms, limitation and affected academic performance were not statistically significant. As most of the women included in the study reported not to have done an adequate amount of exercise, this could be another factor that the prevalence among participants was high.

Another notable finding of this study was the significant association between dysmenorrhea and irregularity of the menstrual cycle. Similarly, a survey by Ameade et al. [25] showed a statistically significant association between the severity of dysmenorrhea and irregularity of menstruation. Also, the menstrual flow and dysmenorrhea were necessary, similar to the results of previous studies [26, 27]. There was a statistically significant association between the type of dysmenorrhea and pain intensity (P = 0.006). The severity of pain was high among women with secondary dysmenorrhea compared to women with primary dysmenorrhea.

Menstrual abnormalities, dysmenorrhea, infertility, chronic pelvic pain (CPP), and dyspareunia are endometriosis's most prevalent clinical indications. Endometriosis symptoms frequently impact patients' social and psychological functioning. As a result, endometriosis is considered a debilitating disease that can jeopardise social interactions and mental health [28]. Endometriosis can be effectively treated with progestins. The effects of the etonogestrel implant on pelvic discomfort, sexual function, and quality of life in women needing long-term reversible contraception and having ovarian cysts of possible endometriotic origin are investigated in the study by Sansone et al. [29]. In patients with ovarian cysts suspected of being caused by endometriosis, etonogestrel implants appear to relieve pelvic discomfort, enhance sexual function, and improve quality of life. Endometriosis is characterised by endometrial-like tissue outside the uterus, which is accompanied by a persistent and inflammatory response. Brasil et al. [30] determined the prevalence and degrees of psychological stress among endometriosis patients. The study showed that multidisciplinary illness management should include mental health assistance inpatient care beyond pain treatment. Moreover, the medical team’s attitude toward the patients’ psychological stress may positively impact their therapy.

It is essential to encourage modifications in the diet and lifestyle of individuals like restricted intake of salt and excessive caffeinated drinks with effective exercising for reducing the severity of dysmenorrhea symptoms. The possible side effects of using analgesics also need to be informed to the women, and they need to be encouraged for other management techniques like the use of hot pads [31, 32]. Measures to deal with dysmenorrhea need to be focused at the school and university level for limiting its interference with the student’s life. Apart from these implications, there were some limitations of this study. For instance, the data was collected using self-administered questionnaires (electronic questionnaires), which decreased the reliability of the results. Moreover, the study only included females from a specific region. The study also fails to compare the sample to the number of Saudi women of reproductive age. As a result, the results just reflect a small portion of the sample. Future studies need to include females from other regions of Saudi Arabia to generalise the results to all Saudi females.

Conclusions

The present study revealed an increased prevalence of dysmenorrhea among Saudi women of reproductive age. This could be due to an unbalanced diet and a low level of exercise seen in the studied group. The intensity of pain was high among women with secondary dysmenorrhea compared to women with primary dysmenorrhea. There was no association of prevalence of dysmenorrhea with the age group or marital status. Campaigns on the information regarding dysmenorrhea and its remedies should be promoted to make the quality of life of women better that could get limited due to menstruation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- PNU:

-

Princess Nourah Bint Abdulrahman

References

Kho KA, Shields JK. Diagnosis and management of primary dysmenorrhea. JAMA. 2020;323:268–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.16921.

Iacovides S, Avidon I, Baker FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update. 2015;21:762–78.

Fajrin I, Alam G, Usman AN. Prostaglandin level of primary dysmenorrhea pain sufferers. Enferm Clin. 2020;30:5–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2019.07.016.

Smith RP. The role of prostaglandins in dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia. In: Dysmenorrhea and Menorrhagia. 1st ed. Boca Raton: Springer. 2018:75–88.

Najimudeen M, Myint MH, Masharudin AW. Reappraisal on the Management of Primary Dysmenorrhoea in Adolescents. Sch Int J Obstet Gynec. 2020;192–9. https://doi.org/10.36348/sijog.2020.v03i09.001

Al-Jefout M, Nawaiseh N. Continuous norethisterone acetate versus cyclical drospirenone 3 mg/Ethinyl estradiol 20 μg for the management of primary dysmenorrhea in young adult women. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2016;29:1437. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2015.08.009.

Speroff L, Fritz MA. Clinical gynecologic endocrinology and infertility. 7th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2005.

Ibrahim NK, Al-Sharabi BM, Al-Asiri RA, Alotaibi NA, Al-Husaini WI, Al-Khajah HA, Rakkah RM, Turkistani AM. Dysmenorrhea among female medical students in King Abdulaziz University Prevalence, Predictors and outcome. Pak J Med Sci. 2015;31:1312. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.316.8752.

Rafique N, Al-Sheikh MH. Prevalence of menstrual problems and their association with psychological stress in young female students studying health sciences. Saudi Med J. 2018;39:67. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2018.1.21438.

Rafique N, AlSheikh MH. Prevalence of menstrual problems and their association with psychological stress in young female students studying health sciences. Saudi Med J. 2018;39:67–73. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2018.1.21438.

Abd El-Mawgod MM, Alshaibany AS, Al-Anazi AM. Epidemiology of dysmenorrhea among secondary-school students in Northern Saudi Arabia. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. 2016;91:115–9. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.EPX.0000489884.20641.95.

Saleem MA. Dysmenorrhea, associated symptoms, and management among students at King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia: An exploratory study. J Family Med Prim Care. 2018;7:769. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_113_18.

Hashim RT, Alkhalifah SS, Alsalman AA, Alfaris DM, Al-Hussaini MA, Qasim RS, Shaik SA. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea and its effect on the quality of life amongst female medical students at King Saud University, Riyadh. Saudi Arabia Saudi Med J. 2020;41:283–9. https://doi.org/10.15537/smj.2020.3.24988.

Ju H, Jones M, Mishra G. The prevalence and risk factors of dysmenorrhea. Epidemiol Rev. 2014;36:104. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxt009.

Burnett M, Lemyre M. No. 345-Primary Dysmenorrhea Consensus Guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2017;39:585–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogc.2016.12.023.

Andersch B, Milsom I. An epidemiologic study of young women with dysmenorrhea. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1982;144:655–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/0002-9378(82)90433-1.

Campbell MA, McGrath PJ. Use of medication by adolescents for the management of menstrual discomfort. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1997;151:905–13. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.1997.02170460043007.

Hailemeskel S, Demissie A, Assefa N. Primary dysmenorrhea magnitude, associated risk factors, and its effect on academic performance: evidence from female university students in Ethiopia. Int J Women’s Health. 2016;2016(8):489–96. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S112768.eCollection.

Subasinghe AK, Happo L, Jayasinghe YL, Garland SM, Gorelik A, Wark JD. Prevalence and severity of dysmenorrhoea, and management options reported by young Australian women. Aust Fam Physician. 2016;45:829–34.

Habibi N, Huang MSL, Gan WY, Zulida R, Safavi SM. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea and factors associated with its intensity among undergraduate students: a cross-sectional study. Pain Manag Nurs. 2015;16:855–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmn.2015.07.001.

Ortiz MI. Primary dysmenorrhea among Mexican university students: prevalence, impact and treatment. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2010;152:73–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.04.015.

Bajalan Z, Alimoradi Z, Moafi F. Nutrition as a potential factor of primary dysmenorrhea: a systematic review of observational studies. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2019;84:209–24. https://doi.org/10.1159/000495408.

Al-Jefout M, Seham AF, Jameel H, Randa AQ, Luscombe G. Dysmenorrhea: prevalence and impact on quality of life among young adult Jordanian females. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2015;28:173–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2014.07.005.

Hailemeskel S, Demissie A, Assefa N. Primary dysmenorrhea magnitude, associated risk factors, and its effect on academic performance: evidence from female university students in Ethiopia. Int J Women’s Health. 2016;8:489–96. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S112768.

Ameade EP, Amalba A, Mohammed BS. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea among University students in Northern Ghana; its impact and management strategies. BMC Womens Health. 2018;18:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-018-0532-1.

Al-Matouq S, Al-Mutairi H, Al-Mutairi O, Abdulaziz F, Al-Basri D, Al-Enzi M, Al-Taiar A. Dysmenorrhea among high-school students and its associated factors in Kuwait. BMC Pediatr. 2019;19:80. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12887-019-1442-6.

Tomás-Rodríguez MI, Palazon-Bru A, Martínez-St John DR, Navarro-Cremades F, Toledo-Marhuenda JV, Gil-Guillén VF. Factors associated with increased pain in primary dysmenorrhea: analysis using a multivariate ordered logistic regression model. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2017;30:199–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpag.2016.09.007.

Laganà AS, La Rosa VL, Rapisarda AM, Valenti G, Sapia F, Chiofalo B, Rossetti D, Frangež HB, Bokal EV, Vitale SG. Anxiety and depression in patients with endometriosis: impact and management challenges. Int J Women’s Health. 2017;9:323.

Sansone A, De Rosa N, Giampaolino P, Guida M, Laganà AS, Di Carlo C. Effects of etonogestrel implant on quality of life, sexual function, and pelvic pain in women suffering from endometriosis: results from a multicenter, prospective, observational study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;298:731–6.

Brasil DL, Montagna E, Trevisan CM, La Rosa VL, Lagana AS, Barbosa CP, Bianco B, Zaia V. Psychological stress levels in women with endometriosis: systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Minerva Med. 2019;111:90–102.

Aksu H, Özsoy S. Primary dysmenorrhea and herbals. J Health Commun. 2016;1:23. https://doi.org/10.4172/2472-1654.100023.

Savitha V, Roopa D, Sridhara KM. A study to assess the effectiveness of structured teaching programme on knowledge regarding home remedies on reducing dysmenorrhea among adolescent girls at St. Paul’s girls High school. Davangere Asian J Nurs Edu Res. 2016;6:327–30. https://doi.org/10.5958/2349-2996.2016.00061.6.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Center for Promising Research in Social Research and Women’s Studies. Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University for funding this research in 2020–2021

Funding

The research is funded from the Center for Promising Research in Social Research and Women’s Studies. Deanship of Scientific Research at Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Hanadi Bakhsh - conception, analysis, drafting and methodology. Eatedal Algenaimi - drafting and methods. Raghad Aldhuwayhi - drafting and methods. Maha AboWadaan - drafting and methods.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The data was protected for confidentiality when conducting this study. The Institutional Review Board of PNU (Princess Nourah bint Abdulrahman University) approved this study. It was obtained before starting data collection. At the end of the questionnaire, an email was provided for any inquiries from the participants about any unclear questions. All participants were informed that participation was entirely voluntary. Additionally, no name was recorded on the questionnaires, and all of the personal information of participants will be confidentially reserved and kept safe. Informed consent was obtained from all participants All authors reviewed the manuscript and approved it. All methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Bakhsh, H., Algenaimi, E., Aldhuwayhi, R. et al. Prevalence of dysmenorrhea among reproductive age group in Saudi Women. BMC Women's Health 22, 78 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01654-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-022-01654-9