Abstract

Background

Various factors, including menopausal status, educational and social background, culture, and physical and emotional health, may influence women’s perceptions of menopause. This study documents the elements influencing attitudes towards menopause among women in Sarawak, Malaysia.

Methods

A face-to-face interview using a validated questionnaire was conducted with 324 Sarawakian women aged 40–65 to determine the mean age of menopause and perceptions and experiences of menopause among these women.

Results

The mean age ± standard deviation of the women was 51.37 ± 5.91 years. Ninety (27.8%) participants were premenopausal, 124 (38.5%) perimenopausal and 110 (33.7%) postmenopausal. The majority of these women (228; 70.4%) were local indigenous inhabitants of Sarawak. The findings show that 22.5% of the participants agreed that problems during menopause are a natural process. While 21.9% of the participants suggested that menopause should be treated medically, 32.3% argued that natural approaches for menopause symptoms are better than hormonal treatments. Seventy-five per cent of the women agreed that the absence of menses after menopause is a relief; meanwhile, 61.2% stated that menopause causes unpleasant symptoms. Notably, 51.7% were not sure whether women become less sexually attractive after menopause, and 51.1% were uncertain as to whether they feel less of a woman following menopause. Finally, 81.7% of participants were unsure if sexual activity is more enjoyable after menopause, and 71.9% were uncertain whether changes in life during menopause are more stressful. Among the different menopausal stages, the premenopausal group of women were noted to have more positive perceptions of menopause compared to the peri- and postmenopausal women. The study also observed that women with a better educational background generally had more positive perceptions of menopause.

Conclusions

The women’s perceptions of menopause in this study were found to correspond to those in other studies on Asian women. Women with higher levels of education and premenopausal women comparatively expressed more positive opinions regarding menopause. Lastly, most of the women noted that menopausal symptoms are unpleasant, but that the absence of menses after menopause is a relief.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The advancement of modern medicine and improved health care and health care delivery systems have significantly prolonged human life expectancy rates throughout the world. Indeed, in Malaysia, the life expectancy for women has increased from 70.5 years in 1980 to 78.4 years in 2019 [1].

Studies on Malaysian [2,3,4], Asian [5, 6] and European women [7,8,9,10,11] have indicated that the mean age of menopause is between 49.4 years and 51.1 years, with an average mean of 50.7 years; this implies that a considerable proportion of Malaysian women live one-third of their lives beyond menopause.

Menopause is a natural physiological process in a woman’s life. It results from a lack of oestrogen secretion from ovarian follicles, leading to the absence of menstruation [12, 13]. A woman is labelled as ‘postmenopausal’ when she misses her periods for 12 months consecutively [14, 15]. Due to oestrogen deficiency, women develop climacteric symptoms, including vasomotor, physical, and psychological complications and sexual dysfunction symptoms, and become physically unwell [15,16,17].

Women’s perceptions of menopause are influenced by various factors, including their cultural, social and educational background and emotional and physical health [12, 16]. Existing studies have found that sociocultural factors can affect women’s attitude, perceptions and experiences towards menopause [7, 8, 13, 17, 18]. In societies where menopause is viewed positively, symptoms are less common. Numerous studies of Western and Asian women, including Japanese and Chinese women, have documented the cultural aspects of menopause [7, 8, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]. Scholars have indicated that the stigma related to menopause begins in early life due to little knowledge and education besides these cultural and social factors [28,29,30,31]. Understanding this crucial stage of life may change women’s negative attitudes towards menopause, which cause apprehension and adverse emotional states in women dealing with this condition. Changing women’s views about menopause by empowering them with knowledge may, therefore, cause less emotional distress among them.

There is a paucity of research concerning Malaysian women’s perceptions of menopause, and no such studies have been conducted among women in Sarawak, Malaysia. This study thus aimed to address this research gap by exploring Sarawakian women’s attitudes towards menopause.

Methods

Subjects and setting

This cross-sectional study was conducted from December 2017 to May 2018 after approval from the Research and Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. All research methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki. The study was carried out among women aged between 40 and 65 who visited four women’s health camps, a health campaign launched by a collaboration of local women’s NGOs, around Kuching, Bau, Serian and Semantan in Sarawak, Malaysia. The participants were from various demographic backgrounds; the women were either from rural, semi-urban or urban areas and held different levels of educational experience ranging from no formal education to tertiary-level education.

All women who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. The inclusion criteria consisted of women between the ages of 40 and 65 who had given written consent. Those who were pregnant, breast-feeding, had uncontrolled medical conditions such as hypertension, diabetes mellitus or heart diseases or any other chronic diseases, were undergoing treatment for cancer or were in remission, or had a history of drug or alcohol abuse, were excluded from the study. Those undertaking hormone replacement therapy were also excluded.

Assessment instrument

A semi-structured questionnaire was used for this study. The questionnaire was divided into three sections, detailed as follows:

-

(1)

The socio-demographic data of the women, which included age, marital status, age of marriage, age of menarche, race, religion, educational level, occupation and average household income.

-

(2)

The women’s menopausal status, which was classified according to the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop (STRAW) categorisation [15]. STRAW divides menopause staging into postmenopausal (no menstrual bleeding in the previous 12 months); late perimenopause (menstruation in the last 12 months but not in the last two months; early perimenopause (increasing irregularity of menses without skipping periods; seven days’ difference from the beginning of a given cycle to the next, experienced after the previous regular cycle) and premenopause (minor changes in cycle length, particularly a decreasing cycle length). The early and late perimenopausal transition stages were combined and classified as the perimenopausal stage to aid statistical analysis [14].

-

(3)

The women’s perceptions of menopause, measured using a questionnaire based on the Menopause Attitudes Scale questionnaires constructed by Lieblum and Swartzman [32], local beliefs, and a focus group interview comprising nine, randomly selected menopausal women.

With the help of experienced health workers and language experts, the questionnaire was then created and reviewed by two gynaecologists and a public health professor to ascertain its validity. It consists of 10 items and initially used a 5-point scale (where 1 = strongly agree, 2 = agree, 3 = not sure, 4 = disagree, 5 = strongly disagree). However, after a pilot study of 30 women, nurses and lecturers to validate the constructed questionnaires, some modifications were made to the grading method of each item due to difficulties faced by the women to grade their agreement on the scale. Thus, the scale was reduced to three items: ‘agree’, ‘disagree’ and ‘not sure’. Factor analysis was performed on the modified questionnaire with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.803 to 0.832, indicating that the questionnaire had good reliability.

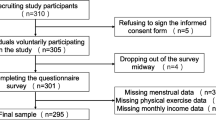

Interviews were conducted face-to-face in the Malay language; the national language is widely spoken in Malaysia by trained health personnel, and its use was crucial in helping participants to understand questions and give correct answers. During registration, participants who fulfilled the criteria were invited to participate in the study. Explanations were given and written informed consent was obtained. A total of 386 women were invited to participate.

Statistical analysis

The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Software Version 25.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL) was used for analyses. Data were presented as mean ± standard deviations (SD), median and percentages. The X2 test was applied to compare the categorical data. The p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Three hundred and eighty-six women aged 40–65 were invited to participate in this study. Sixty-two participants either did not provide consent, had medical problems, or did not complete the interviews or questionnaire; thus, 324 women completed the study.

The mean age ± SD of the women was 51.37 ± 5.91 years. The mean age at menopause for postmenopausal women was 52.34 ± 3.21 years, while the mean age of menarche among all the women was 11.71 ± 2.14 years, and the mean age of marriage was 19.24 ± 2.27 years. Among the women, 90 (27.8%) were premenopausal, 124 (38.5%) perimenopausal and 110 (33.7%) postmenopausal. Most of the women (228; 70.4%) were local indigenous women of Sarawak; indigenous groups of people in Sarawak include the Iban, Bidayuh, Malay, Melanau, Lumbawang, Kelabit, Kayan and Penan peoples. One hundred and sixty-six participants were Christians (51.23%), and 232 were married (71.60%). The majority (282; 87.03%) had received a formal education; 155 (47.83%) were housewives and 122 (37.4%) had a monthly household income below RM 1,000 (USD 238; 1 USD = RM 4.2; see Table 1).

Table 2 presents the women’s perceptions and attitudes towards menopause. As can be seen, 22.5% of the participants agreed that problems in menopause are a natural process. Approximately 21.9% argued that menopause should be treated medically, while 32.3% suggested that natural approaches are preferable to hormonal treatments for menopause symptoms. The majority of the women (75.0%) agreed that the absence of menses after menopause is a relief; nonetheless, 61.2% indicated that menopause causes unpleasant symptoms. Perhaps surprisingly, only 28.1% of the respondents agreed that they look forward to not worrying about pregnancy after menopause. Meanwhile, 51.7% of the women expressed uncertainty regarding whether women become less sexually attractive after menopause, and 51.1% were unsure if they feel less of a woman following menopause. Lastly, 81.7% of the women were not sure if sexual activity is more enjoyable after menopause, and 71.9% were uncertain as to whether changes in life during menopause are more stressful. Among the menopausal stages, the premenopausal group of women were noted to have the most positive perceptions followed by perimenopausal and postmenopausal women (Table 3). In this study, women with higher educational backgrounds (particularly those with a tertiary-level education) exhibited a more positive attitude towards menopause (Table 4).

Discussion

Various factors determine a woman’s perceptions of menopause. Indeed, menopausal status, social background, education, occupation, physical or emotional health, and general symptoms may influence women’s attitudes towards menopause [18, 19]. While menopause has been extensively investigated elsewhere, studies concerning menopause are limited in Malaysia.

Many studies focusing on both Asian women and women globally have reported mixed responses regarding women’s perceptions of menopause and how they, their society, or their communities view menopause. Similar observations were found in this study: more than 50% of the women interviewed were unable to measure or were not sure of their perceptions on menopause [2, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26].

In his study, Ismail [2] suggested that 16% of women regard menopause as a ‘pity’; meanwhile, 60% were pleased, and 24% felt it did not matter. NorHayati [20] found that 73.1% of women did not view menopause as a medical condition, while 71.7% did not feel less of a woman after menopause.

A study conducted in Thailand by Chirawathul et al. [21] observed that rural women regarded menopause as a simple and natural biological event which requires no treatment; they also expressed relief that they no longer need to worry about pregnancy after menopause. Mazhar et al. [22] suggested that Pakistani women have different views about menopause. According to the authors, few participants saw menopause as a medical condition requiring treatment; the majority considered it a natural transition. In contrast, most of the women (69.1%) in the present study were not sure as to whether menopause is a medical problem or not.

In recent years, two community studies in Taiwan [23, 24] indicated that Taiwanese women were highly aware of menopause (97%), with a very positive and accepting attitude towards menopause. They also demonstrated a considerable willingness to receive medical treatment. Another study by Leon et al. [25] focused on middle-age Ecuadorian women who exhibited positive attitudes towards menopause: 93.7% viewed it as a normal event and not a problem; 65.3% expressed relief at the diminished risk of pregnancy, and 60.7% reported that life is more straightforward and calmer.

Finally, Sinclair et al. [26] found that 80% of women agreed with the view that because reduced hormone levels bring about the menopause, it should be viewed as a medical condition and treated as such. The majority of these participants (76.2%) also disagreed that a woman feels less of a woman after menopause. Conversely, in the present study, only 22.5% agreed menopause is a natural process; 21.9% argued that menopause should be treated medically, and just 24.2% of the respondents feel like less of a woman following menopause.

This study found that most of the women (69.1%) were uncertain whether to treat menopause medically, while 62.1% were unsure if a more natural approach, using traditional, herbal or alternative medicine, was better than a hormonal method.

In contrast, in a study among Kelantanese women in Malaysia [20], NorHayati noted that 73.1% of her respondents did not view menopause as a medical condition. Similarly, Chirawathul et al. [21] also suggested that Thai women regarded menopause as a simple and natural biological event which requires no treatment. Mazhar et al. [22], in their study concerning Pakistani women, reported that few respondents viewed menopause as a medical condition requiring treatment; rather, the majority considered it a natural transition. In Larroy et al.’s [33] study in an Asian context, menopause is treated as a natural process of ageing and associated with higher social status and wisdom among the communities. Conversely, a study by Sinclair et al. [26] found that the majority of their respondents agreed with the view that because diminished hormone levels bring on the menopause, it should be viewed as a medical condition and treated as such. In two Taiwanese community studies [23, 24], meanwhile, women were highly aware of menopause (97%), exhibiting a positive, accepting attitude and great willingness to receive medical treatment.

Most of the respondents in the present study (75.0%) agreed that the absence of menses after menopause is a relief, although 61.2% noted that menopause causes unpleasant symptoms. However, only 28.1% agreed that they look forward to not worrying about pregnancy after menopause. These findings correspond with Leon et al.’s study [27] focusing on middle-age Ecuadorian women. The researchers observed positive attitudes towards menopause, where 93.7% of respondents viewed it as a normal, unproblematic event; 65.3% expressed relief at the diminished risk of pregnancy, and 60.7% reported that life is easier and calmer. Another study by Chirawathul et al. [21] noted that Thai women felt better after menopause as they no longer have to worry about pregnancy. Finally, Wong et al. [27] found that their participants, consisting of middle-aged women in Kuala Lumpur, held positive attitudes towards menopause. While most agreed that menopause indicates loss of youth and fertility and a sign of ageing, others argued that menopause is simply a part of growing old and involves freedom from menstruation, pregnancy and childbirth. Negative attitudes towards menopause, such as treating it as a disease, no longer feeling like a real woman or feeling old and useless, and the loss of drive to perform daily chores were rejected by most participants. Surprisingly, however, despite the prevalence of positive attitudes towards menopause, many participants also expressed nervousness, fear and sadness about approaching menopause [27].

One could conclude, from this study’s findings, that the majority of the respondents refuted the idea that menopause and sexual activity are related. Indeed, only 2.8% of the women agreed that sex is more enjoyable after menopause; meanwhile, 34.8% argued that women are less sexually attractive after menopause and 24.2% feel like less like a woman after menopause.

When comparing the status or stages of menopause, those with positive perceptions of menopause in this study were generally among the premenopausal group. The same findings were noted by Larroy et al. [33], Wong et al. [27] and several other studies focusing on Asian and European women, where positive perceptions were shared more by younger women than older women in their postmenopausal stages [20, 21, 23, 25].

Levels of education and background were also positive influences among women regarding menopause: the present study, along with several others, found that women with a stronger educational background generally have a better and more positive perception of menopause [6, 14, 28,29,30,31,32,33].

Literacy and knowledge concerning menopause can be increased by various methods, such as arranging health talks in the community and using social media platform. Malaysia, and especially Sarawak, has a mixed population of urban and rural. In remote areas where internet access is sporadic, community participation and engagement through initiatives like health camps play a prominent role in educating women regarding menopause. While it was challenging to transfer knowledge about menopause to women with low education levels, it was inspiring to share knowledge among more highly educated women, particularly in an urban setting, where the potential of social media can be utilised at its fullest in educating not only women but also the general population.

While collecting data, some participants appeared to express reservations about sensitive questions, especially those regarding sex. This could be due to the norms of Malaysian and Asian society, whereby women are reluctant to openly discuss this topic. Another limitation was the difficulty in translating the question into different local dialects/languages; however, in order to minimise this effect, the researcher conducted face-to-face interviews with the help of a translator and explanation was given to respondents who had problems understanding the questions.

Conclusions

The study of the perception of menopause among Sarawak women between the ages of 40 and 65 showed the mean age of menopause was 52.34 ± 3.21 years. Participants’ attitudes towards menopause differ from those reported in other studies based in Malaysia and other Asian countries. This discrepancy could be because of misunderstandings or misconceptions regarding menopause among Sarawak women. Educational background has a significant effect on how women perceive menopause: the higher the educational level, the more positive the perception of menopause. Moreover, since menopause is an issue which is not generally discussed openly in most eastern communities, including among Sarawak women, there seems to be lack of information, knowledge and awareness regarding menopause; this was reflected in the answers given during the interviews.

Primary care providers, including primary care physicians, play an essential role in educating and creating awareness among women of all ages about menopause since primary care providers are the first point of contact with formal health care providers for individuals, families and communities.

Availability of data and materials

The data used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. World Population Prospects; 2019. https://population.un.org/wpp/.

Ismael NN. A study on the menopause in Malaysia. Maturitas. 1994;19(3):205–9.

Abdullah B, Moize B, Ismail BA, Zamri M, Mohd Nasir NF. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms, its effect to quality of life among Malaysian women and their treatment seeking behaviour. Med J Malays. 2017;72(2):94–9.

Dhillon HK, Singh HJ, Rashidah S, Abdul Manaf H, Nik Mohd Zaki NM. Prevalence of menopausal symptoms in women in Kelantan, Malaysia. Maturitas. 2006;54:213–21.

Peeyananjarassri K, Cheewadhanaraks S, Hubbard M, Zoa Manga R, Manocha R, Eden J. Menopausal symptoms in a hospital-based sample of women in southern Thailand. Climacteric. 2006;9:23–9.

Loh FH, Khin LW, Saw SM, Jeannette JM, Ken Gu. The age of menopause and the menopause transition in a multiracial population: a nation-wide Singapore study. Maturitas. 2005;52:169–80.

Jurgenson JR, Jones EK, Haynes E, et al. Exploring Australian Aboriginal Women’s experiences of menopause: a descriptive study. BMC Women’s Health. 2014;14:47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-14-47.

Jones EK, Jurgenson JR, Katzenellenbogen JM, et al. Menopause and the influence of culture: another gap for Indigenous Australian women? BMC Women’s Health. 2012;12:43. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6874-12-43.

Dennerstein L, Duddley EC, Hopper JL, Guthrie JR, Burger HG. A perspective population-based study of menopausal symptoms. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;96:351–8.

McKinlay SM, Brambilla DJ, Posner JG. The normal menopause transition. Maturitas. 1992;14:103–15.

Gold EB, Block G, Crawford S. Lifestyle and demographic factors in relation to vasomotor symptoms: baseline results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1189–99.

Sut HK, Sut N. Severity of menopausal symptoms in climacteric Turkish woman. Int J Caring Sci. 2017;10(1):382–439.

Ibraheem OM, Oyewole OE, Olaseha IO. Experiences and Perceptions of Menopause among women in Ibadan South East Local Government area, Nigeria. Afr J Biomed Res. 2015;18:81–94.

Greendale GA, Lee NP, Arriola ER. The menopause. Lancet. 1999;353:571–80.

Soules MR, Sherman S, Parrot E. Executive summary: stages of reproductive aging workshop (STRAW). J Women’s Health Gender-Based. 2001;10(9):843.

Lee I, Wang HH. Pattern and related factors of self-care behavior among perimemenopausal women. Public Health Q. 2001;28:151–60.

Shanafelt TD, Barton DL, Adjei AA, Loprinzi CL. Pathophysiology and treatment of hot flashes. Mayo Clin Proc. 2002;77:1207–18.

Theisen SC, Mansfield PK, Seery BL. Predictors of midlife women’s attitudes toward menopause. Health Values. 1995;19(3):22–31.

McKinlay SM, Avis NE. A longitudinal analysis of women’s attitudes toward the menopause: results from the Massachusetts women’s health survey. Maturitas. 1992;13:65–79.

NorHayati H. A study of menopausal experience, attitude towards menopause and the practice of hormone replacement therapy among post-menopausal women attending Klinik Kesihatan Bandar, Kota Bahru, Kelantan. Universiti Sains Malaysia (USM). 32; 1999.

Chirawatkul S, Manderson L. Perception of menopause in Northeast Thailand: contested meaning and practice. Soc Sci Med. 1994;39(11):1545–54.

Mazhar SB, Gul-e-Erum S. Knowledge and attitude of older women towards menopause. J Coll Phys Surg Pak. 2003;13(11):621–4.

Pan HA, Wu MH, Hsu CC, Yao BL, Huang KE. The perception of menopause among women in Taiwan. Maturitas. 2002;41(4):269–74.

Cheng MH, Wang SJ, Wang PH, Fuh JL. Attitudes toward menopause among middle-aged women: a community survey in an island of Taiwan. Maturitas. 2005;52:348–55.

Leon P, Chedraui P, Hidalgo L, Ortiz F. Perceptions and attitudes toward the menopause among middle aged women from Guayaquil, Ecuador. Maturitas. 2007;57(3):233–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.maturitas.2007.01.003.

Sinclair HK, Bond CM, Lewin KJ. Women’s knowledge of and attitudes towards hormone replacement therapy. Fam Pract. 2003;20:112–9.

Wong LP, Nur Liyana AHA. Survey of knowledge and perception of menopause among young to middle-aged Women in Federal Territory, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. JUMMEC. 2007;10(2):22–30.

Gebretatyos H, Ghirmai L, Amanuel S, et al. Effect of health education on knowledge and attitude of menopause among middle-age teachers. BMC Women’s Health. 2020;20:232. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-020-01095-2.

Sultan S, Sharma A, Jain NK. Knowledge, attitude and practices about menopause and menopausal symptoms among midlife school teachers. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol. 2017;6(12):5225.

Moridi G, Shahoei R, Khaldi S, Sayedolshohadaei F. Quality of life among Iranian postmenopausal women participating in a health educational program. Chronic Dis J. 2013;1(2):63–6.

Taherpour M, Sefidi F. The effectiveness of education on the knowledge and attitude towards menopause symptoms and complications in postmenopausal women. J Adv Med Biomed Res. 2013;25:92–101.

Lieblum SR, Swartzman LC. Women attitude towards menopause: an update. Maturitas. 1986;8:47–56.

Larroy C, Quiroga-Garza A, González-Castro PJ, et al. Symptomatology and quality of life between two populations of climacteric women. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23:517–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-019-01005-y.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the study coordinators, especially nursing staff for their untired work and the women of Sarawak who voluntarily participated in this study.

Funding

There was no funding source for this study, so the decision to publish and all the aspects of this study, are the responsibility of the authors alone.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SASAR designed the study, participated in conception coordinated recruitment of participants, education of participants, training of health personnel’s, preparing of teaching materials, literature search, data analysis and editing of manuscript. BIB assured of quality of data collection, coordinated in participant’s recruitment, writing of all the drafts, assisted in drafting manuscript, and literature search. AI designed the study, participated in the conception coordinated recruitment of participants, education of participants, literature search, data analysis, and editing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to publication

Ethics approval was obtained from Research and Ethics Committee, Faculty of Medicine, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak. All participants provided written informed consent. Confidentiality and anonymity were ensured.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Syed Alwi, S.A.R., Brohi, I.B. & Awi, I. Perception of menopause among women of Sarawak, Malaysia. BMC Women's Health 21, 77 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01230-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-021-01230-7