Abstract

Background

In the Netherlands, palliative care is provided by generalist healthcare professionals (HCPs) if possible and by palliative care specialists if necessary. However, it still needs to be clarified what specialist expertise entails, what specialized care consists of, and which training or work experience is needed to become a palliative care specialist. In addition to generalists and specialists, ‘experts’ in palliative care are recognized within the nursing and medical professions, but it is unclear how these three roles relate. This study aims to explore how HCPs working in palliative care describe themselves in terms of generalist, specialist, and expert and how this self-description is related to their work experience and education.

Methods

A cross-sectional open online survey with both pre-structured and open-ended questions among HCPs who provide palliative care. Analyses were done using descriptive statistics and by deductive thematic coding of open-ended questions.

Results

Eight hundred fifty-four HCPs filled out the survey; 74% received additional training, and 79% had more than five years of working experience in palliative care. Based on working experience, 17% describe themselves as a generalist, 34% as a specialist, and 44% as an expert. Almost three out of four HCPs attributed their level of expertise on both their education and their working experience. Self-described specialists/experts had more working experience in palliative care, often had additional training, attended to more patients with palliative care needs, and were more often physicians as compared to generalists. A deductive analysis of the open questions revealed the similarities and distinctions between the roles of a specialist and an expert. Seventy-six percent of the respondents mentioned the importance of having both specialists and experts and wished more clarity about what defines a specialist or an expert, how to become one, and when you need them. In practice, both roles were used interchangeably. Competencies for the specialist/expert role consist of consulting, leadership, and understanding the importance of collaboration.

Conclusions

Although the grounds on which HCPs describe themselves as generalist, specialist, or experts differ, HCPs who describe themselves as specialists or experts mostly do so based on both their post-graduate education and their work experience. HCPs find it important to have specialists and experts in palliative care in addition to generalists and indicate more clarity about (the requirements for) these three roles is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The need for palliative care is increasing due to a growing population of individuals with dementia, cancer, or other life-threatening or incurable diseases [1,2,3]. Palliative care aims to improve the quality of their life and that of their families [4,5,6]. Palliative care is an approach to alleviating physical, psychosocial, and spiritual suffering in patients and their families facing a life-threatening illness [4]. This approach intends to integrate palliative care methods and procedures in general care settings [7]. As so many people need palliative care, it has been argued that all healthcare professionals (HCPs) should be able to provide it. This entails, among other things, that HCPs should be able to provide advance care planning, align treatment with a patient’s goals, wishes, and needs, and essential symptom management, avoid futile or burdensome treatments, and care for people who are dying [8,9,10].

In complex care situations, however, generalists may be supported by palliative care specialists. [11,12,13]. This support pertains to consultation on palliative care issues or the transfer of care when this is indicated [14, 15]. This collaboration between generalists and specialists is considered to be essential for the quality of care [16,17,18]. Brinkman et al. described that specialist palliative care has positive effects on the quality of life, and the symptom burden of patients with advanced cancer has increased over the past years [19]. Temel [20] stated that involving specialized palliative care early in the trajectory improves multiple outcomes among patients with advanced cancer and their caregivers. Boddaert et al. [21] described that early provision of specialist palliative care for patients with advanced disease of frailty strongly relates to a better quality of life, less depression and anxiety, and higher satisfaction with care.

Therefore, a so-called ‘mixed model’ of palliative care, combines primary-level palliative care (i.e., skills that all HCPs should have or ‘palliative care generalists’) with specialty-level palliative care (i.e., skills for managing more complex and challenging cases or ‘palliative care specialists’) [7, 22]. Such a mixed generalist-specialist model decreases the likelihood of potentially inappropriate end-of-life care for patients [21] and promotes overall satisfaction with care [23].

Most countries nowadays distinguish between general and specialized palliative care [24, 25] including the Netherlands. However, in the Netherlands, it is not yet clear what exactly this distinction entails. Although a competency framework for the generalist in palliative care has been established, on which there is nationwide consensus, such a framework does not yet exist for the specialist in palliative care [26]. Palliative care is not a formal specialty in the Netherlands. Although different training programs in palliative care are available, it is unclear through which training you become a palliative care specialist.

In the Netherlands Quality Framework for Palliative Care (NQFPC), broad descriptions are given of the generalist and specialist. In addition, an expert in palliative care is recognized (see Table 1). However, these descriptions are very general and do not provide sufficient clarity and precision. For instance, it is unclear which training and competencies are needed to become a specialist or expert in palliative care and how the role of a specialist relates to the role of a generalist in palliative care practice. The NQFPC also does not specify when and how specialists and generalists should collaborate. Furthermore, the NQFPC distinguishes a third level of expertise: the role of an expert [27]. However, no clear definition is given of the expert in palliative care and we neither found such a description in international literature.

This unclarity may undermine the quality of palliative care. For instance, it may delay the initiation and referral to specialized palliative care [28, 29]. In addition, as a well-defined competency profile for specialists is lacking, and it is unclear whether people can call themselves ‘specialists’ after completing a course in palliative care.

In this study, we aim to explore how HCPs working in palliative care described themselves in terms of generalist, specialist, and expert, based on the description of the Netherlands Quality Framework for Palliative Care (NQFPC) [27, 30] and how this self-description is related to work experience and education. Our secondary aim is to explore differences between the role of generalists and the combined role of specialist/ expert regarding work characteristics and to explore considerations of all HCPs regarding the distinction between palliative care specialists and experts.

Methods

Design and setting

A cross-sectional study was carried out using an open online survey. The survey period lasted for five months (May -September 2022). This study is embedded in the Dutch ‘Optimizing Education and Training in Palliative Care’ (O2PZ) program, which aims to accomplish that every HCP in the Netherlands has the right competencies to provide high-quality palliative care [31].

Population

The target group of the survey concerns all HCPs of every Netherlands qualification framework (NLQF) level who have an affinity with and/or provide palliative care. The NLQF level is based on the European Qualifications Framework (EQF), consisting of eight levels of learning outcomes. In the Netherlands, we use the following distinctions: nurse assistants are trained at NLQF levels 2 and 3, nurse intermediate vocational levels at NLQF level 4, and bachelor nurses at NLQF level 5 or 6. Clinical nurse specialists and Physician Assistants (PA) are trained at NLQF level 7, and physicians and specialized physicians at NLQF level 8 and 8+. These levels are based on knowledge, skills, independence, and responsibilities [32].

Recruitment

The survey was published in digital newsletters, and on websites of organizations like the Dutch Society of Professionals in Palliative Care (Palliactief) and via Linkedin. The Dutch Nurses Association (V&VN) disseminated the questionnaire among their members, including nurse assistants, nurses (bachelor and vocation level), clinical nurse specialists. HCPs affiliated with the O2PZ program were asked to share the questionnaire with other HCPs, especially those who provide palliative care at the bedside.

Variables and data collection

The questionnaire (see additional file 1) consisted of 16 mostly closed but also some open-ended questions. Except for question 13, and 3 out of 5 items of question 14, all questions have been analyzed for this article. Question 13 and parts of question 14 deal with when to consult a specialist or expert, which will be discussed in another article.

The primary outcome of this study is the self-description of HCPs working in palliative care regarding their role as generalists, specialists, or experts in palliative care and how this is related to their work experience and education. We focus on the threefold generalist – specialist – expert. This was measured by asking questions 11 and 12 (see additional file 1).

To compare generalists with the combined role of specialists and experts, we also collected demographic and work-related characteristics, such as age, sex, current work setting, number of patients seen in the last year, and current job title (questions 1 to 7). It is expected that HCPs will not have a clear description of what they mean by specialist or expert and what distinguishes them or is similar, so we decided to combine the roles of specialist and expert (Table 5).

The considerations of HCPs working in palliative care and the distinction and similarities between the role of specialist and expert were collected using two open questions, 14 and 15.

The questionnaire was developed by five researchers based on their practical and academic experiences in palliative care (authors IZ, SM, FG, BOP, and HOM) and based on relevant peer-reviewed literature [33, 34]. In the literature, we searched for competencies that fit HCPs specialized in palliative care. Forbat et al. [9] stated that communication and listening competencies are described as typical skills for palliative care specialists. Brown et al. [14] noted that specialists should have skills for managing complex and difficult cases and co-exist to support generalists through consultation care and transfer of care. Gamondi et al. [7] described ten core interdisciplinary competencies in palliative care. Radbruch et al. [35] developed a framework that described the standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe.

The content and structure of the questionnaire were presented to a working group. The authors approached potential participants for the working group using the following selection criteria: gender, affinity with palliative care, and a mix of generalists and specialists working in different healthcare domains. The working group comprised ten healthcare providers: five nurses and five physicians.

The questionnaire was adjusted based on their feedback. It was conducted using the survey tool Survalyzer provided by Amsterdam UMC.

Analysis

Quantitative analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Respondents who did not work in direct patient care were excluded. Respondents who did not describe themselves as generalist, specialist, or expert based on education or based on work-experience were categorized as generalists because of their initial education as HCPs. Thereby, we followed Boddaert et al. [27, 30] who described in the National Quality Framework Palliative Care: In the Netherlands, all HCPs are expected to provide generalist palliative care, informed by national standards and guidelines. Palliative care specialists can be consulted to provide support and expert advice [14, 22, 29, 36]. This was also stated by Gamondi [7] in the Core Competencies in Palliative Care by the European Association Palliative Care: “All healthcare professionals and workers should be able to provide appropriate palliative care and thus need to be trained to provide the highest possible standards of care to meet the challenging needs of patients and families, irrespective of diagnosis”.

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize baseline characteristics of healthcare professionals and to describe the number and percentages of self-described roles of HCPs, based on work experience and education. Hereby, we used the threefold distinction of generalist—specialist—expert, based on the context in the Netherlands and described in the Netherlands Quality Framework for Palliative Care (NQFPC) [27, 30]. A Chi-square test was used to test for significant differences between self-description based on education or work experience and other characteristics.

Secondly, we analyzed differences between generalists and the combined roles of specialist and expert. We combined the roles of specialist and expert because, in the international literature, the role of an expert was not recognized as a role next to the role of a specialist [36,37,38,39]. In Dutch palliative care practice, these roles are used interchangeably. Because of the number of tests, p values <.01 were considered statistically significant.

Questions 14 and 15 (open-ended questions regarding the distinction between specialist and expert palliative care) were analyzed deductively, based on the role description of specialist and expert in the NQFPC [27, 30] using Excel. Answers were read and re-read by the first and third authors, and the final analyses were discussed with all authors.

Ethics

All respondents were carefully informed about the study objectives and were asked for informed consent, which was the survey’s first question. An email with information about consent and confidentiality of the survey data was sent. The email also included a link to the online questionnaire. The question for consent was the first question of the online questionnaire, which stated: ‘Do you consent to use your answers to the questions in the questionnaire for research purposes?’

If this question was answered positively, the respondents could continue the questionnaire; if they did not give permission, they could not continue the questionnaire. Informed consent was obtained from all the respondents. All data were collected and analyzed anonymously. We performed our study in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of the Declaration of Helsinki. According to the Medical Research Involving Human Subjects Act, our study is exempted by formal review by an ethics committee [40, 41]. Participants were not asked to act or to change behaviors, and the questions were not of a drastic nature. According to Dutch law (WMO) [40] no permission is required from an Ethic Committee [41], only a self-check of the Saxion Ethics Advise Ethic Committee (SEAC).

Results

Respondent characteristics

The online survey was accessed 1002 times, and 854 participants consented to use their answers/data and filled out the questionnaire. The final number of participants differed per question. Of the participants, 87% were female, 55% were older than 51 years, 28% worked in home care, 21% worked in a hospital and almost 18% worked in a hospice setting (Table 2). Most participants had a profession as a bachelor or vocational trained nurse or physician. 32% of respondents had more than 20 years of work experience in palliative care. 33% of the respondents provided palliative care to more than 60 patients annually. 74% of the respondents followed additional training for palliative care.

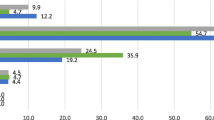

Based on the descriptions of generalist, specialist, and expert palliative care in the Netherlands Quality Framework for Palliative Care (NQFPC, Table 1), most respondents described themselves as either a specialist or an expert: based on education, this was respectively 31% and 38%. The number of participants who described themselves as specialist or expert, based on work experience, was respectively 34% and 44% (Table 3). 17% of the respondents described themselves as a generalist based on work experience and 25% described themselves as a generalist based on education.

Table 4 shows a significant difference in self-description when self-description is based on education or work experience (p<0.001). 23% of the participants gave a different self-description in terms of generalist, specialist, or expert in palliative care if the basis was education or work experience; 70% of the participants gave the same self-description when this was based on education or work experience.

Table 5 shows the differences and similarities between self-described generalists and specialists/experts. It also distinguishes self-description based on education from self-description based on work experience.

Generalists were often nurse assistants or nurses on a vocational level, while specialists and experts were more often Bachelor Nurses or physicians.

Generalists and specialists/experts all worked in different healthcare settings. Generalists worked more often in nursing homes than specialists/experts, who mostly worked in hospitals and hospices. In other work settings, only minor differences were seen between percentages of generalists versus specialists/experts. Specialists/experts had significantly more years of work experience in general care and palliative care than generalists. This counts for specialists/experts based on education and specialists/experts based on work experience.

Specialists/experts saw more patients with a palliative need annually than generalists; this counted for both specialists/experts based on education and for specialists/experts based on work experience. More than 90% of the specialists/experts followed additional training, as compared to 64% of the self-described generalists. Specialists/experts mostly followed a postgraduate education: nurses (51%) and physicians (28%). Of the respondents who received the same training, some described themselves as generalists, whereas others described themselves as specialists/experts.

The similarities and differences between specialists and experts in palliative care

Respondents were asked whether they find it important to have specialists and experts in palliative care (question 14). 76% of all respondents answered that having specialists and experts in palliative care is important. There was no difference in answers between respondents describing themselves as generalists (76%) or specialists/experts (76%) based on education and respondents describing themselves as generalists (76%) or specialists/experts (75.5%) based on work experience. They were asked to provide further explanation by means of an open question (question 15). The analyses revealed two themes: teamwork and differentiation. Codes by the theme of teamwork were 1) consultation and 2) the importance of collaboration. Codes by the theme differentiation were 1) distinction in required competencies, 2) importance of having both, 3) the need for clarififying the mixed model palliative care, and 4) leadership as specialist.

Teamwork

Respondents described the importance of collaboration and consultation between generalists, specialists, and experts to the quality of palliative care: “Through good cooperation with specialists and experts, palliative care will increase in quality. Especially when it becomes a recognized position within the care provision” (Clinical nurse specialist, self-description: specialist).“Good cooperation is very important between generalist and specialist and between specialist and expert".

Respondents indicate that they think it is important for generalists to know what they can consult specialists/experts about. “They must consult each other timely, be aware of their boundaries, and know their limits when someone else needs to be called in” (Bachelor Nurse, self-description: specialist).

Differentiation

Respondents were asked to further explain their answers about the distinctive elements of the role of specialist and expert (question 15). Many respondents maintain there is an overlap in the competencies and roles of specialist and expert, such as collaboration and consultation. Respondents distinguished specialists from experts by mentioning that the expert has outstanding competencies in a specific area of palliative care, is fully committed to palliative care, and has a leading role in consultation, research, and in palliative care initiatives. “For me, a palliative care expert is someone who, in addition to providing good palliative care, also shows responsibility in optimizing palliative care at the meso and macro level. Examples are developing transmural care pathways, setting up training courses for nurses to become specialists, initiating quality projects, and participating in projects. The expert has a consultation function, access to a multidisciplinary network, and can work in an interprofessional team” (Physician, self-description: specialist). ”I think the cooperation between the specialist, who is executive, and the expert who coordinates and advises is important” (Physician, self-description: generalist).

Some respondents, however, argue that specialists also have a leading role, whereas experts distinguish themselves by fully focusing in palliative care: “Specialists mainly have a leading role in organizing palliative care in the department, and the surplus of experts is that they have palliative care as their core business” (Physician, self-description: expert). Finally, some respondents indicated that experts do not necessarily have patient contact, whereas others think they do.

Furthermore, respondents considered long-term work experience to be a requirement of being an expert. For instance, as a nurse argued: “Not only by education but also by work experience you make the step from specialist to expert. You become an expert not only through theoretical knowledge but also through work experience” (Bachelor Nurse, self-description: expert).

Yet, respondents (including respondents that answered yes to the statement that the distinction between specialist and expert is important) also considered the distinction between the role of specialist and expert as ambiguous and arbitrary and even doubted the existence of this distinction: “In my opinion, the difference between a specialist and an expert is difficult to distinguish, and the question is whether it is necessary. What is paramount is the cooperation between specialists and experts in executive, consulting, and continuing tasks”(Vocational level, self-description: expert). “I still find it difficult to use this dichotomy. Especially because I have a specialist education and sufficient experience (5 years) and am involved in both medium and highly complex situations, but I work part-time as a district nurse and part-time as an expert in palliative care. How should I describe myself?” (Bachelor Nurse, self-description: no description).“I think it is a very arbitrary distinction. In practice, we do not use the terms that way either. You have a generalist, and you have a specialist. It would be best if you did not also want to add an expert in the field of work” (Physician, self-description: specialist).

Need for clarification

Some respondents argued for the necessity of additional training to become a specialist or an expert in palliative care. They stressed that it should be very clear which competencies are trained, and for which role you are being trained. As one respondent noted: “Now it is easy to say that someone specializes in palliative care, but what education or training did they receive for that? Sometimes this is said after a few hours of training ” (Bachelor Nurse, self-description: generalist).

Respondents also described that education level plays a role in becoming a specialist or expert; they mentioned that only HCPs with higher graduate education, such as bachelor nurses, clinical nurse specialists, and physicians, can become specialists or experts. “It is a difficult distinction between specialist and expert. Maybe the level of education in general? Only clinical nurse specialists and physicians can become specialists or experts ”(Physician, self-description: specialist).

The importance of clarity and recognition of educational programs is stressed: “The palliative care courses [should be] legally recognized with an official title” (Bachelor Nurse, describes himself as a specialist), and: “There are so many different courses in palliative care. Create an unambiguous curriculum” (Bachelor Nurse, describes himself as a specialist). “Which (accredited) education and work experience you must have to describe yourself as a specialist or expert is, in my opinion, not determined; it helps if we determine this” (Physician, self-description: specialist).

Finally, respondents stressed the importance of an unambiguous profile for specialists and experts, which is recognized nationally: “Establish a national professional profile for specialists and palliative care experts.”

Discussion

Main findings

Our findings show that most respondents described themselves as specialists or experts in the Dutch mixed model palliative care and less often as generalists. Three out of four HCPs indicated having the same level of expertise based on training as based on working experience.

Characteristics of self-described specialists/ experts significantly differ from the characteristics of self-described generalists. Self-described specialists/experts are more often bachelor nurses, clinical nurse specialists, and physicians; generalists are more often nurse assistants and vocational-level nurses. Specialists/ experts more often followed additional or postgraduate education than generalists. They had more years of work experience in palliative care than generalists. Those who describe themselves as specialists/experts also care for more patients with incurable conditions or high vulnerability than generalists on an annual basis.

Almost all respondents (76%) find it important to have palliative care specialists in addition to generalists. However, respondents indicate the need for a clear profile of specialists and possibly experts, which is recognized nationally. Furthermore, the difference between a specialist and an expert is not clear to many respondents, some of whom even doubt the need for the role of expert in addition to the specialist.

Interpretation of findings

Our results show that HCPs describes themselves as generalist, specialists, and experts on divergent grounds. Although 76% of respondents self-describe themselves on the same level of expertise based on training as based on working experience, there is a group that self-describes themselves differently based on education and based on work experience. Above that the comparison of background characteristics of self-described generalists and specialists/experts does show a tendency towards more palliative education and work experience for specialists/experts, but does also show diversity in self-description. There are for instance respondents that followed post-graduate education that consider themselves a generalist while others consider themselves a specialist or expert.

The question is what causes this diversity. The first reason is that post-graduate education in palliative care is relatively new in the Netherlands. Since the beginning of this century, there have been training courses for nurses and physicians who want to specialize in palliative care, for nurse assistants these courses have not (yet) been developed. Many respondents in this study already had a long time of work experience in palliative care and it could be possible that not everyone has had the opportunity to follow additional training on palliative care. This might explain the importance of work experience for the role of specialist or expert in palliative care.

A second possible explanation for the diversity in self-description can be caused by the premise that every HCP must be able to provide palliative care in the Netherlands [27].

Therefore, every HCP, nurse as well as physician is a generalist based on his graduate education. Many generalists work in nursing homes, where a lot of palliative care is provided. Generalists have received less additional training in palliative care, but because there are few palliative care specialists or experts working in their immediate environment, generalists may unknowingly provide specialist palliative care [21]. It is likely that this can cause role confusion and this affects the self-description. In addition, it can lead to late referrals to recognized specialists in palliative care or consultation teams, which compromises the quality of care [14, 24, 25].

A third possible explanation is that many HCPs have indicated that the distinction between specialist and expert is unclear. This is in line with the ambiguity found in the literature. The NQFPC [27] describes a threefold division: generalist- specialist- expert, but in literature, the dichotomy generalist - specialist palliative care is mainly described as mixed model palliative care [42,43,44,45]. Due to the different views on the distinction between specialist and expert, there is confusion about professional identity and self-description.

The fourth explanation is that our results also show that respondents with the same completed education in palliative care describe themselves as generalist, specialist, and expert. Hence, it needs to be clarified which education leads to the role of specialist or expert and which education is meant for generalists. In the Netherlands, a framework was recently established for generalist education in palliative care on different educational levels [26]. However, such a recognized framework is lacking for specialized palliative care, while examples are available from international literature. Autelitano et al. (2021) described a first draft of the competencies of the specialist palliative care nurses (only in hospitals) in Italy, based on the white paper on palliative care training of the European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC) [7, 46,47,48]. This can only be established if there is consensus regarding the role and competencies of specialist palliative care professionals.

Finally, the fifth explanation possibly relates to the special mixed model in the Netherlands, the threefold generalist – specialist – expert. In the open answers, there appears to be a lot of confusion about the roles of specialist and expert, and both differences and similarities are described. No literature has been found on the role of expert and the possible surplus of this role. Similarities have been found in respondents' beliefs regarding the roles and competencies of the specialist and expert, such as consultation and collaboration; these are aligned with the core competencies in palliative care described in the white paper of EAPC [7], such as consultation and leadership roles.

A Delphi study is recommended to reach a consensus on role description, competencies, and criteria as to which education you become a specialist or an expert and how we can define relevant work experience [49,50,51]. A recognized educational framework could also clarify the titles and roles of palliative care in healthcare organizations.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this study is that we collected data from HCPs of all educational (NLQF) levels and from all care settings in which palliative care is provided. This provides insight into how a broad range of HCPs that provide palliative care describe themselves, and on what basis. Some limitations should also be mentioned. Although we used different avenues to recruit HCPs, selection bias could have occurred: respondents with an affinity with palliative care may have been overrepresented. This is indicated by the fact that our respondents mainly call themselves specialists or experts. Furthermore, we included relatively few respondents who were nurse assistants or nurses at the vocational level. In reality, this is a relatively large group within healthcare and provides a major part of palliative care at the bedside. In addition, HCPs who participated in this study were most often at an advanced age and had a long work experience in palliative care. We expect this to have influenced the outcomes, for instance on the importance of work experience for becoming a specialist.

Conclusions

Among HCPs working in palliative care in the Netherlands, 17 % describe themselves as a generalist, 34% as a specialist, and 44% as an expert based on work experience. Almost three out of four HCPs gave the same self-description when this was based on their education and their working experience.

We showed considerable differences between generalists versus specialists/experts regarding function, work experience (in palliative care), the number of patients seen annually, and postgraduate education. Participants also mentioned similarities between specialists and experts in being consulted and the importance of collaborating and having a leadership role. HCPs (76%) find it important to have specialists and experts in palliative care in addition to generalists. Still, the Dutch participants need more clarity about the distinction between both roles and with which education and work experience you become a specialist or an expert. We, therefore, recommend reaching a consensus about the role description and competencies of specialists and experts and how these roles relate to general palliative care, including educational requirements and relevant work experience.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- HCPs:

-

Healthcare professionals

- NQFPC:

-

Netherlands Quality Framework for Palliative Care

- O2PZ:

-

Optimizing Education and Training in Palliative Care

- NLQF:

-

Netherlands Qualification Framework

- EQF:

-

European Qualification Framework

- PA:

-

Physician Assistant

- PC:

-

Palliative Care

- V&VN:

-

Dutch Nurses Association

References

Jeba J, Taylor C, O’ Donnel V. Projecting palliative and end-of-life care needs in Central Lancashire up to 2040: an integrated palliative care and public health approach. Public Health. 2021;195:145–51.

van Gaans D, Erny-Albrecht K, Tieman J. Palliative Care Within the Primary Health Care Setting in Australia: A Scoping Review. Public Health Rev. 2022;43:1604856. https://doi.org/10.3389/phrs.2022.1604856. PMID: 36148429; PMCID: PMC9485459.

Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, Salsberg ES. The Growing Demand for Hospice and Palliative Medicine Physicians: Will the Supply Keep Up? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(4):1216–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.011.

WHO. World Health Organisation Definition palliative care. 2002. https://www.who.int/health-topics/palliative-care.

Sepúlveda C, Marlin A, Yoshida T, Ullrich A. Palliative Care: the World Health Organization’s global perspective. J Pain Symptom Manage Augustus. 2002;24(2):91–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00440-2. PMID: 12231124.

van Riet Paap J, Vernooij-Dassen M, Brouwer F, Meiland F, Iliffe S, Davies N, et al. Improving the organization of palliative care: identification of barriers and facilitators in five European countries. Implement Sci. 2014;9:130 Epub 2015/02/1.

Gamondi C, Larkin P-J, Payne S. Core competencies in palliative care. Eur J Palliat Care. 2013;20:86–91.

Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, Lovell N, Evans CJ, Higginson IJ, Murtagh FEM. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med. 2017;15(1):102. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-017-0860-2.

Forbat L, Johnston N, Mitchell I. Defining “specialist palliative care” findings from a Delphi study of clinicians. Aust Health Rev. 2020;44(2):313–21. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH18198,. PMID: 31248475.

Grant MS, Back AL, Dettmar NS. Public Perceptions of Advance Care Planning, Palliative Care, and Hospice: A Scoping Review. J Palliat Med. 2021;24(1):46–52. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0111. PMID: 32614634.

Thorns A. Identifying those in need of specialist palliative care. BMJ. 2019;365:l4115.

Wikert J, Gesell D, Bausewein C, Jansky M, Nauck F, Kranz S, Hodiamont F. Specialist palliative care classification: typology development. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2022:bmjspcare-2021-003435. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003435. Epub ahead of print.

van Doorne I, Willems D.L, Baks, N, de Kuijper J., Buurman B.M, , van Rijn M. Current practice of hospital-based palliative care teams: Advance care planning in advanced stages of disease: A retrospective observational study. PREPRINT (Version 1) available at Research Square [10.21. 18 October 2021.

Brown CR, Hsu AT, Kendall C, Marshall D, Pereira J, Prentice M, Rice J, Seow HY, Smith GA, Ying I, Tanuseputro P. How are physicians delivering palliative care? A population-based retrospective cohort study describing the mix of generalist and specialist palliative care models in the last year of life. Palliat Med. 2018;32(8):1334–43.

Luckett T, Phillips J, Agar M, et al. Elements of effective palliative care models: a rapid review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14:136.

Jordan K, Aapro M, Kaasa S, Ripamonti CI, Scotté F, Strasser F, Young A, Bruera E, Herrstedt J, Keefe D, Laird B, Walsh D, Douillard JY, Cervantes A. European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) position paper on supportive and palliative care. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(1):36–43. https://doi.org/10.1093/annonc/mdx757.

Morrison RS, Dietrch J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultations teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiciaries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2011;30:454–63.

Hui D, Bruera E. Models of Palliative Care Delivery for Patients With Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(9):852–65. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.18.02123.

Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Vergouwe Y, Booms M, Hendriks MP, Peters LA, van Quarles Ufford-Mannesse P, Terheggen F, Verhage S, van der Vorst MJDL, Willemen I, Polinder S, van der Heide A. The ImpactThe Impact of Palliative Care Team Consultation on Quality of Life of Patients with Advanced Cancer in Dutch Hospitals: An Observational Study. Oncol Res Treat. 2020;43(9):405–13.

Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small -cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–42.

Boddaert MS, Pereira C, Adema J, Vissers KCP, van der Linden YM, Raijmakers NJH, Fransen HP. Inappropriate end-of-life cancer care in a generalist and specialist palliative care model: a nationwide retrospective population-based observational study. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2022;12(e1):e137–45. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002302. Epub 2020 Dec 22. PMID: 33355176; PMCID: PMC9120402.

Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care—creating a more sustainable model. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(13):1173–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1215620.

Bakitas MA, Tosteson TD, Li Z, Lyons KD, Hull JG, Li Z, et al. Early versus delayed initiation of concurrent palliative oncology care: patient outcomes in the ENABLE III randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(13):1438–45.

Connolly M, Ryan K, Charnley K. Developing a palliative care competence framework for health and social care professionals: the experience in the Republic of Ireland. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care . 2016, 237-242.

Sakashita A, Shutoh M, Sekine R, Hisanaga T, Yamamoto R. Development of a Consensus Syllabus of Palliative Medicine for Physicians in Japan Using a Modified Delphi Method. Indian J Palliat Care. 2019;25(1):30–40. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_122_18. PMI.

O2PZ. Onderwijsraamwerk palliatieve zorg 2.0. https://palliaweb.nl. [Online] oktober 17, 2020. https://palliaweb.nl/onderwijs/interprofessioneelopleiden/download-onderwijsraamwerk-2-0.

Connolly M, Ryan K, Charnley K. Developing a palliative care competence framework for health and social care professionals: the experience in the Republic of Ireland. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2016;6(2):237–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2015-000872.

Cannon ST, Gabbard J, Walsh RC, Statler TM, Browne JD, Marterre B. Concordant palliative care delivery in advanced head and neck cancer. Am J Otolaryngol. 2023;44(1):103675. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjoto.2022.103675. Epub 2022 Oct 21. PMID: 36302326; PMCI.

VUmc. Onderwijsraamwerk palliatieve zorg 1.0. Amsterdam: s.n., 2017. https://palliaweb.nl/onderwijs/interprofessioneelopleiden/download-onderwijsraamwerk-2-0.

Boddaert MS, Douma J, Dijxhoorn AQ, Héman RACL, van der Rijt CCD, Teunissen SSCM, Huijgens PC, Vissers KCP. Development of a national quality framework for palliative care in a mixed generalist and specialist care model: A whole-sector approach and a modified Delphi technique. PloS one. 2022;17(3):e0265726. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265726.

O2PZ. www.O2PZ.nl. [Online] 2018. http://www.o2pz.nl.

European-qualifications-framework. https://europa.eu. [Online] 2022. https://europa.eu/europass/en/european-qualifications-framework-eqf.

Van Trigt I, Dijxhoorn F, Van de Camp K, Douma J, Boddaert M. Pressure points in palliative care in the primary care setting (original: Knelpuntenanalyse Palliatieve zorg in de Eerstelijn). Utrecht: IKNL/Palliactief; 2017.

de Bruin J, Verhoef MJ, Slaets JPJ, van Bodegom D. End-of-life care in the Dutch medical curricula. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7(5):325–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0447-4,. PMID: 30187388; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6191393.

Radbruch L, Payne S. White Paper on standards and norms for hospice and palliative care in Europe: part 2. Eur J Palliat Care. 2010;17(1):22–33.

Kang J, Kim Y, Yoo YS, Choi JY, Koh SJ, Jho HJ, Choi YS, Park J, Moon DH, Kim DY, Jung Y, Kim WC, Lim SH, Hwang SJ, Choe SO, Jones D. Developing competencies for multidisciplinary hospice and palliative care professionals in Korea. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(10):2707–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-013-1850-3. Epub 2013 May 25 PMID: 23708823.

Abbasi J. New Guidelines Aim to Expand Palliative Care Beyond Specialists. JAMA. 2019;322(3):193–5. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.5939. PMID: 31241716.

Ballou JH, Brasel KJ. Teaching Palliative Care in Surgical Education. AMA J Ethics. 2021;23(10):E800-805. https://doi.org/10.1001/amajethics.2021.800. PMID: 34859774.

Centeno C, Clark D, Lynch T, et al. Facts and indicators. Facts and indicators on palliative care development in 52 countries of the who European region: results of an EAPC Task force. Palliat Med. 2007;1:463–71.

CCMO. Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects. [Online] [Cited: October 30, 2023.] https://english.ccmo.nl/.

Wet Medisch Wetenschappelijk onderzoek met mensen (WMO). www.wettenoverheid.nl. [Online] [Cited: April 8, 2024.] https://wetten.overheid.nl/BWBR0009408/2024-01-01.

Bolegnesi D, Centano C, Biasco G. Specialisation in palliative medicine for physicians in Europe: a supplement of the EAPC atlas of palliative care in Europe. Milan: European Association for Palliative Care Press; 2014.

AAHPM. American Academy of Hospice Palliative Medicine (AAHPM). ,. ABMS sub-specialty certification in hospice and palliative medicine. [Online] 2014. http://aahpm.org/certification/subspecialty-certification.

MRCPUK. Members of the Royal College of Physicians United Kingdom (MRCPUK). Specialty training in Palliative Medicine. [Online] 2017. https://www.mrcpuk.org/mrcpuk-examinations/specialty-certificate-examinations/specialties/palliative-medicine.

Teoli D, Schoo C, Kalish VB. Palliative Care. StatPearls . February 2023, pp. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan–. PMID: 30725798.

Autelitano C, Bertocchi E, Artioli G, Alquati S, Tanzi S. The Specialist Palliative Care Nurses’ in an Italian Hospital: role, competences, and activities. Acta Biomed. 2021;92(S2):e2021006. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v92iS2.11360. PMID: 33855987; PMCID: PM.

Hökkä M., Mitrea N. Taksforce EAPC Innovation in nurse education palliative care. EAPC. [Online] June 20, 2023. https://nursedupal.eu/.

Chen X, Zhang Y, Arber A, Huo X, Liu J, Sun C, Yuan L, Wang X, Wang D, Wu J, Du J. The training effects of a continuing education program on nurses' knowledge and attitudes to palliative care: a cross sectional study. BMC Palliat Care. 2022, 26.

Sinha IP, Smyth RL, Williamson PR. Using the Delphi technique to determine which outcomes to measure in clinical trials: recommendations for the future based on a systematic review of existing studies. PLoS Med. 2011;8(1):e1000393. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000393.

Slade SC, Dionne CE, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Standardised method for reporting exercise programmes: protocol for a modified Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006682. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006682. PMID: 25550297; PMCID: PMC4281530.

Boulkedid R, Abdoul H, Loustau M, Sibony O, Alberti C. Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2011;6(6):e20476. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020476. Epub 2011 Jun 9. PMID: 21694759.

Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of palliative care into standard oncology care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2016;35:96–112. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2016.70.1474. PMID: 2803.

Kaasa S, Loge JH, Aapro M, et al. Integration of oncology and palliative care: a Lancet Oncology Commission. Lancet Oncol. 2018;19:e588–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30415-7. PMID: 30344075.

Brinkman-Stoppelenburg A, Boddaert M, Douma J, van der Heide A. Palliative care in Dutch hospitals: a rapid increase in the number of expert teams, a limited number of referrals. BMC Health Serv Res. 2016;6(1):518 Epub 2016/09/25.

Paal P, Brandstötter C, Elsner F, Lorenzl S, Osterbrink J, Stähli A. Paal P, Brandstötter C. European interprofessional postgraduate curriculum in palliative care: A narrative synthesis of field interviews in the region of Middle, Eastern, and Southeastern. Palliat Support Care. 2022, doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951522001651. Epub ahead of pri,.

Ryan K, Connolly M, Charnley K, Ainscough A, Crinion J, Hayden C, Keegan O, Larkin P, Lynch M, McEvoy D, McQuillan R, O’Donoghue L, O’Hanlon M, Reaper-Reynolds S, Regan J, Rowe D, Wynne M. Palliative Care Competence Framework Steering Group Dublin.

Mosoiu D, Payne S, Predoiu O, Arantzamendi M, Ling J, Tserkezoglou A, Mitrea N, Dionisi M, Martínez M, Mason S, Ancuta C, Centeno C. Core Palliative Care Research Competencies Framework for Palliative Care Clinicians. J Palliat Med. 2023, 2023 Nov 20.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Ingrid van Zuilekom, (Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) ref. 10200022110004.

Suzanne Metselaar, (Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) ref. 10200022110004.

Fleur Godrie, (Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development (ZonMw) ref. 10200022110004.

Bregje Onwuteaka_Philipsen, no funding.

Harmieke van Os-Medendorp, no funding.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

List of abbreviations: I.v.Z = Ingrid van Zuilekom, S.M = Suzanne Metselaar, F.G = Fleur Godrie, B.O-P = Bregje Onwuteaka-Philipsen, H.v.O-M = Harmieke van Os-Medendorp I.v.Z, S.M. B.O-P, and H.v.O-M developed the study design I.v.Z and F.G collected the data I.v.Z and H.v.O-M analyzed the data I.v.Z wrote the main manuscript All authors co-wrote the manuscript F.G co-wrote the manuscript as a junior researcher S.M B.O-P and H.v.O-M co-wrote the full manuscript as a senior researcher H.v.O-M supervised in the process I.v.Z Acknowledgements: Not applicable.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

van Zuilekom, I., Metselaar, S., Godrie, F. et al. Generalist, specialist, or expert in palliative care? A cross-sectional open survey on healthcare professionals’ self-description. BMC Palliat Care 23, 120 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-024-01449-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-024-01449-9